By Charles Burress

A U.S. Army officer’s refusal to go to Iraq has touched off an intense, at times furious debate among Japanese Americans, reopening an unhealed wound that dates back to World War II.

Many news articles, op-ed pieces and emotional letters to the editor in the Japanese-American press have featured the case of 1st Lt. Ehren Watada, a Japanese American native of Honolulu stationed at Fort Lewis in Washington state. Army officials say he’s the first commissioned officer to refuse orders to deploy to Iraq, on the principle established by the Nuremberg war-crimes trial that he is obliged to disobey illegal or immoral orders.

The 28-year-old Watada is expected to be court-martialed and faces a possible seven years in prison, not just because of his refusal to deploy on June 22 but also because of public comments accusing the Bush administration of lying to Congress and the American people about the justifications for the invasion of Iraq. His statements, according to the Army charges against him, make him guilty of “contempt toward officials” and “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman,” each of which are crimes under the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

The case, which could put the war’s legality on trial in a military courtroom, has garnered a moderate amount of mainstream media coverage, as well as an amicus court filing from the American Civil Liberties Union, which supports his free-speech rights. It also drew three well-known and distinguished critics of the war who testified on his behalf at a preliminary hearing at Fort Lewis on Aug. 17: Denis Halliday, former UN Assistant Secretary General in charge of humanitarian relief in Iraq in the late ‘90s; retired Army Col. Mary Ann Wright, who began a second career at the State Department and was the number two official at the U.S. embassy in Mongolia in March 2003 when she abruptly resigned in protest of the Iraq invasion, making her the highest ranking among the three diplomats who quit in protest that month; and Francis Boyle, an expert in international law at the University of Illinois College of Law and a specialist on military law and civil disobedience.

Yet, the most intense emotional heat generated by the case has centered among Japanese Americans. Some see Watada as tarnishing the legendary proof of their patriotism – the sacrifice of Japanese Americans who fought and died in large numbers for the United States in World War II, even as many of their families were forced out of their homes, deprived of their property and relocated by the U.S. government to internment camps. The heroism of these Nisei, or second-generation, Japanese-American soldiers is a famous chapter in the annals of the U.S. military.

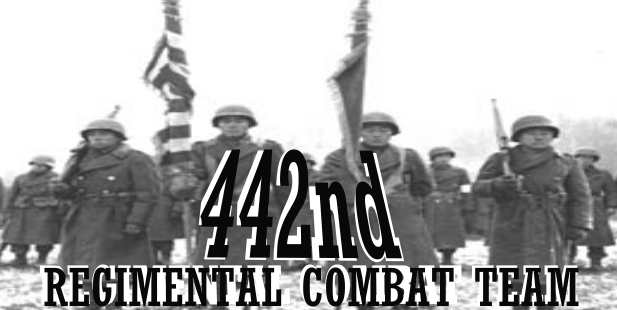

“Rarely has a nation been so well-served by a people it has so ill-treated,” President Clinton said in June 2000 as he awarded the nation’s highest military tribute, the Medal of Honor, to 20 Japanese-American veterans of World War II, including a U.S. Senator from Watada’s home state, Daniel Inouye, who lost an arm in the fighting. “For their numbers and length of service, the Japanese Americans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, including the 100th Infantry Battalion, became the most decorated unit in American military history.”

More than 33,000 Japanese Americans served in the war, including those in the Military Intelligence Service, Women’s Army Corps, Army Nurse Corps and other support roles, according to a history compiled by the National Japanese American Memorial Foundation.

Not surprisingly, Watada’s stance has been condemned by many, though by no means all, Japanese-American veterans and their organizations.

“He is bringing shame to the JAs (Japanese Americans),” Bob Wada, charter president of the Japanese American Korean War Veterans, told the Pacific Citizen, newspaper of the Japanese American Citizens League. “The guys that were killed in action … they must be turning over in their graves that a JA is refusing to go to war.”

Fred Oshima, a columnist for the San Francisco-based Nichi Bei Times, denounced “Watada’s selfish military antics.” He quoted with approval the statement issued by Henry Wadahara, former commander of the California division of the VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars): “Refusing a deployment is a dishonor and a slap in the face to all who have served so bravely. Our 105,000 members stand behind me in saying we are not supporting Watada’s decision to disobey a lawful order. Ehren Watada has violated the oath he took as an officer in the United States Army. He’s betrayed the men and women who are putting their lives on the line every day out there working to make the lives of the Iraq people better.”

But other Japanese Americans have joined anti-war activists and demonstrations supporting Watada. Some place him in the tradition of Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, hailing him as a hero willing to sacrifice his own future to resist an unjust war.

“Regardless of dove or hawk, we all now know that the American people, and our ally countries, were deliberately lied to about why we needed to go to Iraq,” wrote Sharon Maeda of Seattle to the Pacific Citizen. “And now, over 2,500 of our young men and women have died. What is most sad is to learn that he’s one of — if not THE first –officer to have the guts to stand up and do what is right, despite the consequences to himself. THAT is true American patriotism.”

Among those who lent support in a series of rallies and appearances in the San Francisco Bay Area in late August were San Francisco’s elected Public Defender, Jeff Adachi; the executive director of San Francisco’s Japanese Cultural and Community Center, Paul Osaki; and award-winning filmmaker Steven Okazaki. His family has rallied around him, with his father, Bob Watada, the recently retired executive director of Hawaii’s election watchdog agency, the Campaign Spending Commission, making dozens of appearances on the West Coast and in Hawaii. And a web page, http://www.thankyoult.org, has been set up to funnel information and aid.

Lt. Watada with his parents Carolyn Ho and Robert Watada (Photo Jeff Paterson)

An ad hoc group of Sacramento-area supporters, who call themselves Asian Pacific Islanders for Peace, issued a statement that endorsed Watada’s position and also displayed a special sensitivity shared by many Japanese Americans to the War on Terror’s impact on Muslim Americans. “Like Japanese Americans after imperial Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, our Middle Eastern American neighbors have been unjustly blamed for the actions of others.”

But the chief reason for Japanese American sensitivity to the Watada case may lie elsewhere. Among his supporters are those who not only see a big difference between World War II and the Iraq invasion but also recall a different, less publicized side to the Japanese American experience in World War II. Not all Japanese-Americans rushed to prove their loyalty by joining the military.

A few refused to go to the internment camps, including Fred Korematsu, whose conviction was belatedly and famously overturned by a federal appeals court in 1984 and who was awarded the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, in 1998 by President Clinton.

“An even larger group of 12,000 Japanese Americans, a tenth of the internees, dissented on the so-called loyalty oath,” Japanese American Citizens League member Andy Noguchi told Nichi Bei Times readers in a guest column. “They answered ‘No,’ qualified their answers, or refused to respond to this insulting questionnaire. In 1943, they became known as the disloyal ‘No-No Boys,’ and the Tule Lake Segregation Center became their home for the duration.” The two questions were whether they would serve in combat for the U.S. military and whether they would swear allegiance to the United States while renouncing allegiance to the Japanese Emperor or any other foreign power. In addition to American citizens of Japanese descent, a large percentage of internees had been born in Japan. Having been barred in that era from becoming U.S. citizens, many of them declined to answer yes because they didn’t want to become stateless by renouncing their Japanese allegiance.

A third category of protesters consisted of more than 300 Nisei draft resisters, who refused to obey their draft orders while their families were held in internment camps. Most of them were sent to federal prison for an average term of three years.

The bitter split between the protestors and those who fought for the U.S. is mirrored today in the Watada dispute, said Noguchi, civil rights co-chair for the JACL’s Florin chapter near Sacramento.

“A lot of the people who took part in that protest and answered no to the loyalty oath have been labeled as trouble-makers and disloyal for decades,” Noguchi said in an interview. “A lot of people were ostracized at that time. Many kept it secret from their children and grandchildren.”

“It’s been very difficult,” he continued. “It’s torn apart families. Communities have been divided. Even to this day, some people on opposite sides of that fence won’t talk to each other.”

Central to the dispute is the JACL, which calls itself “the nation’s oldest Asian American civil and human rights organization.” It played a leading role in supporting and cooperating with the government in the relocation and in condemning protesters. Differences of opinion over what exactly it did and what it should have done have persisted for many years, as illustrated by the uproar in 2000 and 2002 when Noguchi helped organize national JACL efforts to achieve long-delayed reconciliation over the Nisei draft resisters.

The legacy of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, including the 100th Infantry Battalion, plays an important role in the Japanese-American debate over Lt. Watada.

So history weighed heavily when the JACL was confronted with the Watada case. In the end, it refused to take a stand on Watada’s refusal to go to Iraq. It declared in July that his situation “is not, per se, a civil rights case” and is “beyond the reach of the JACL’s authority based on the organization’s mission statement.” Said Nichi Bei Times columnist Oshima, “To take a daring supportive position with this lively issue for Watada would’ve been suicidal for JACL.” Yet, at the same time, the JACL statement, which has been prominently featured on its home page, argues at length against punishing Watada for his opinions. And an interview with him has been featured at the top of the home page for the Pacific Citizen, the JACL newspaper (pacificcitizen.org).

And while the long shadow of the past can be seen in the battles over Watada and the war, Nichi Bei Times columnist Chizu Omori sees the dispute as an indicator of continuing second-class status for Japanese Americans today. “All of us JAs, according to some, are still expected to be a ‘credit to our race,’ and conversely, we bring ‘shame’ to our community if we behave, in their eyes, in some unacceptable manner,” she wrote. “It strikes me as evidence that some of us still operate as though we are second class citizens who have to be on our best behavior at all times…That he (Watada) happens to be a JA is coincidental and really irrelevant to the issues at hand. We ought to be arguing over the merits of the war rather than harp on the shame Watada brings on the JA community.”

Watada himself does not frame the issue in terms of his Japanese American identity. He has cited his duty as an American citizen and U.S. Army officer. In public statements quoted by the Army at the Aug. 17 hearing, Watada made clear the principles behind his objections to the war:

“My moral and legal obligation is to the Constitution and not those who would issue unlawful orders,” he said in a June 7 statement. “…It is my conclusion as an officer of the Armed Forces that the war in Iraq is not only morally wrong but a horrible breach of American law. Although I have tried to resign out of protest, I am forced to participate in a war that is manifestly illegal… My participation would make me party to war crimes.”

“This is a war not out of self-defense but by choice, for profit and imperialistic domination,” he said in an Aug. 12 speech at a Veterans for Peace convention in Seattle. “WMD, ties to Al Qaeda, and ties to 9/11 never existed and never will…Our narrowly and questionably elected officials intentionally manipulated the evidence presented to Congress, the public, and the world to make the case for war…. Neither Congress nor this administration has the authority to violate the prohibition against pre-emptive war — an American law that still stands today. This same administration uses us for rampant violations of time-tested laws banning torture and degradation of prisoners of war.”

Lt. Watada speaking to Veterans for Peace

“‘I was only following orders’ is never an excuse,” he said. “The Nuremberg Trials showed America and the world that citizenry as well as soldiers have the unrelinquishable obligation to refuse complicity in war crimes perpetrated by their government. Widespread torture and inhumane treatment of detainees is a war crime. A war of aggression born through an unofficial policy of prevention is a crime against the peace. An occupation violating the very essence of international humanitarian law and sovereignty is a crime against humanity.”

Watada had a very different view in March 2003 when the U.S. invaded Iraq. A senior at Hawaii Pacific University, he enlisted in the Army that month in response to President Bush’s call to join the war on terrorism and began active duty after graduating that June.

After serving in Korea, he learned he would be dispatched to Iraq.

“I realized that to go to war, I needed to educate myself in every way possible,” he told journalist Sarah Olson in an interview for Truthout.org. “Why were we going to this particular war? …I began reading everything I could.

“One of many books I read was James Bamford’s Pretext for War. As I read about the level of deception the Bush administration used to initiate and process this war, I was shocked. I became ashamed of wearing the uniform. How can we wear something with such a time-honored tradition, knowing we waged war based on a misrepresentation and lies? It was a betrayal of the trust of the American people. And these lies were a betrayal of the trust of the military and the soldiers.

“The deciding moment for me was in January of 2006. I had watched clips of military funerals. I saw the photos of these families. The children. The mothers and the fathers as they sat by the grave, or as they came out of the funerals. One really hard picture for me was a little boy leaving his father’s funeral. He couldn’t face the camera so he is covering his eyes. I felt like I couldn’t watch that anymore. I couldn’t be silent any more and condone something that I felt was deeply wrong.”

Watada’s offered to resign or to serve in Afghanistan instead but was turned down.

When his unit, the 3rd Stryker Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division, left Fort Lewis on June 22, he refused to board the plane. He has been reassigned to administrative tasks on base while the Army reviews his case and is free to come and go when off duty.

Few doubt Watada’s sincerity. In his report on the Aug. 17 hearing at Fort Lewis, the Army’s investigating officer, Lt. Col. Mark Keith, wrote, “I do believe 1LT Watada is sincere in his beliefs. This…should mitigate any future punishments.” However, Keith also concluded that “the defense argument regarding the war is a political question and therefore irrelevant.” He recommended that Watada face a general court-martial on all charges.

On Watada’s public comments, Keith said Watada’s “contempt for the President serves to break down the good order and discipline of all military personnel by casting doubt regarding his integrity and leadership attributes while under the stress of combat operations.” In addition, Keith said Watada’s refusal to deploy and “his contempt for the President while in an official capacity dishonor and/or disgrace him as a U.S. Army officer.”

On the case against Watada, JACL has commented that the contempt charge “is a broad and little-used provision of military law which was applied during the civil war and again during World War I. Its last known application was in 1965 when an officer protested the war in Vietnam. However, during the impeachment of Bill Clinton, numerous military officers critical of the president wrote articles and public letters that expressed insulting opinions of, and contempt toward, the commander in chief, but none of these officers was disciplined.”

On Watada’s refusal to deploy, his claim that he has a right and an obligation under Nuremberg principles to disobey illegal orders presents a touchy issue for the Army.

“How effective of an Army would we have if we allowed our soldiers — especially officers — to refuse to comply with military orders just because they did not agree?” wrote retired Col. Harry Fukuhara of San Jose to the Pacific Citizen.

In his report, Lt. Col. Keith wrote, “The defense contends every officer is duty bound to evaluate each order given for legal sufficiency. I agree. However, due to the complexity of U.S. and International law, I believe it would be very difficult for Army officers to determine the legality of combat operations (nor should they attempt to do so) ordered by the President of the United States of America/Commander in Chief. Individuals should seek clarification of orders they believe are unclear or improper and should rely upon official interpretations or approvals of those orders unless definitively illegal.”

Keith’s closing term, “unless definitively illegal,” suggests the ambiguity that lingers in the U.S. military over the Nuremberg principle that America played a leading role in establishing.

This issue is addressed in equivocal terms by the US Army Field Manual No. 27-10 “The Law of Land Warfare.” It says, “In considering the question whether a superior order constitutes a valid defense, the court shall take into consideration the fact that obedience to lawful military orders is the duty of every member of the armed forces; that the latter cannot be expected, in conditions of war discipline, to weigh scrupulously the legal merits of the orders received; that certain rules of warfare may be controversial; or that an act otherwise amounting to a war crime may be done in obedience to orders conceived as a measure of reprisal. At the same time it must be borne in mind that members of the armed forces are bound to obey only lawful orders (e. g., UCMJ, Art. 92).”

That telltale last sentence references Article 92 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which says that a member of the armed services who “violates or fails to obey any lawful general order … shall be punished as a court-martial may direct.” By inference, a soldier is not obliged to obey unlawful orders.

The Army seems to agree that Watada doesn’t have to obey illegal orders, but it also asserts that he does not have the authority to determine what orders are unlawful.

Boyle, the University of Illinois expert on international law who testified for Watada at the Fort Lewis hearing, acknowledged that the determination of an order’s legality is subjective but cited Nuremberg, saying it is up to the individual soldier to make that determination.

Watada has said he is prepared to accept the consequences of his decision.

In the Pacific Citizen interview, conducted by Executive Editor Caroline Aoyagi-Stom, he said, “I knew joining the Army, whether it was fighting in a foreign war or now fighting for the rights of soldiers, meant sacrifice. In combat, you may lose a limb, bodily functions, or your life. Speaking out against an authoritarian government and refusing to obey their unlawful orders may mean loss of liberty and other less than pleasant things. These are both sacrifices and commitments made to the American people as an American soldier. I gave my life to protect freedom and democracy — a sacrifice I am willing to make by doing the right thing.

“In a way I’m already free. Physically they can lock me up, throw away the key, leave me to rot and contemplate my ‘crimes.’ For a long time I was in turmoil. I felt compelled to fulfill the terms of my contract despite what I knew to be utterly wrong. Only when I realized that I served not men and institutions but the people of this country, did I believe there was another answer. That choice was to do what is right and just.”

Following standard procedure, the Army is reviewing its investigating officer’s report before deciding the next step. Watada’s attorney, Eric Seitz of Honolulu, put the likelihood of a general court-martial at “100 percent.”

For Michael Honey’s video film, A Soldier’s Duty?, on Lt. Ehren Watada’s

Story challenge to President Bush’s invasion and war in Iraq, see:

Charles Burress covers Asia-Pacific and Asian-American affairs for The San Francisco Chronicle.

He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted on September 12, 2006.

Find the full text of the Pacific Citizen’s August 30, 2006 interview with Lt. Watada here.

Find the full text of John Rockwell’s Counterpunch report: Citizens of Conscience: Military Resistance from the Vietnam War to Iraq here.