The Smallest Army Imaginable: Gandhi’s Constitutional Proposal for India and Japan’s Peace Constitution (1)

C. Douglas Lummis

Prologue

In 1931, on his way to the London Round Table Conference, Mahatma Gandhi was asked by a Reuters correspondent what his program was. He responded by writing out a brief, vivid sketch of “the India of my dreams”. Such an India, he said, would be free, would belong to all its people, would have no high and low classes, no discrimination against women, no intoxicants and, “the smallest army imaginable.” (2)

Gandhi in London in 1931 for the Round Table Conference

The last phrase presents a puzzle: What is the smallest military imaginable? But the fact that it presents a puzzle is also puzzling. For what is so unimaginable about no military at all? The question is not rhetorical, for most people do find the no-military option unimaginable. It is easy enough to pray for peace, to petition and demonstrate for peace, or to imagine oneself as a perfectly pacifist non-killer. It is harder to imagine a state with no military.

One of the few places where this option is clearly and forcefully stated is in Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution. People who first hear about this article often respond by insisting that the words can’t mean what they say. It is, after all, an axiom of politics that states have militaries. This axiom is presumed to hold despite the fact that there exist today 13 countries with no military forces and no military alliances. (3)

“Zero” is easy enough to imagine; what is it that makes it so hard for us to imagine “zero military”? Perhaps one reason is that the things the military is trained to do, and does, are so awful that it is essential to us to believe that they are ABSOLUTELY NECESSARY, and that to allow any hint of a doubt about that to enter our consciousness is unsettling. Moreover, if you start talking about the possibility of zero military you are treated as one who has stepped out of the realm of reality. You risk being called a crank, a dreamer, a peacenik, a wimp or (God help us!) a “Gandhian.”

One might counter that it is natural not to imagine zero military, because what constrains our imagination is the force of reality itself. The idea is simply irrational and unrealistic, and not worth thinking about. But I am convinced that just the opposite is true: this failure of our imagination prevents us from seeing reality; it conceals from us the truth of our situation. It is only when we accept Gandhi’s implicit challenge and carry his “smallest military imaginable” to its extreme conclusion that we can begin truly to think about what the military means in our lives.

The Peace Constitution of Japan

Japan’s post-war Constitution does carry the challenge to its extreme conclusion; its Article 9 imagines the military altogether out of existence.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.

In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as any other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

Taken by itself, Article 9 is a fascinating, bold, lucidly written statement of a new principle of international politics, and a new concept of “the state” itself. Note that this is not an “appeal” for peace, such appeals being a dime a dozen. It does not say that the Government should avoid war insofar as possible, or that it should try as hard as it can to seek peaceful solutions. Rather, the Japanese Constitution is written on the principle of sovereignty of the people. In the Preamble to the previous Meiji Constitution, the grammatical subject is “I”, that is, the Meiji Emperor; the Constitution which follows is often described as his “gift”; in fact it is his command. In the present Constitution this “I” is replaced by “we”, that is, the Japanese people, which means that it takes the form of a command by the people to the government. It sets out the powers that the government has, and the powers it does not have. Article 9 says the government does not have the power to make war, threaten war, or make preparations for war. Therefore, the government does not have those powers. As a legal instrument, it is clear and absolute. The problem is that, as a practical matter, it is enveloped in layer upon layer of hypocrisy. Its formulators, or some of them – members of the post-war U.S. Occupation and of the then Japanese government – may have believed in Article 9 sincerely enough to get it written down, but never enough to have it carried out.

But how is it possible that they could have been sincere at all? Article 9 utterly violates the common sense of politics and political science. How could a group of practical politicians and military people have offered this as a serious proposal?

There are several possible answers to that question.

First, one might, at least tentatively, try taking the authors at their word. It is important to recall the historical moment, and the geographical place, where this Constitution was written. This was immediately after the end of World War II, in Tokyo, a city that had been flattened and burned by the U.S terror bombings. It is said that you could stand in the center of Tokyo and see the horizon in every direction.

Tokyo after the firebombing of March 9-10, 1945

It is probably only partly metaphorical to say that the smell of burning flesh was still not gone from the city. It seems possible that the most hardnosed realist (as the two persons alleged as the forces behind the peace clause, Baron Shidehara Kijuro and General Douglas McArthur, surely were) could read directly off the face of the land that the international system was not operating properly, and that given the technology of modern warfare, the state was no longer able to protect its citizens from violent death. And of course this is also the historical moment when, and the country where, the world entered the age of nuclear warfare. Confronted with these things, unprecedented in history, one would not need to be a pacifist dreamer to see that something was deeply wrong, and that a new principle was needed.

But the US motives were mixed from the beginning. Destroying Japan’s military power was of course a war aim from the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and writing that into the Constitution can be seen simply as a way of nailing down the victory. This was backed by a deep mistrust of Japan on the part not only of the US but the other allied powers (especially those which, like Korea, China, and the Philippines, had been invaded and colonized); from this standpoint the Peace Constitution did not necessarily mean that military force in itself was bad, but that Japan could not be trusted with it. Moreover, McArthur, it turns out, never really believed that a demilitarized Japan would be safe from attack, but rather saw the string of U.S. military bases then under construction, some in Japan but most in tiny Okinawa (which had been seized from Japan and was then under U.S. military governance) as the sine qua non that would make the Japanese Peace Constitution possible. (4) McArthur was able to imagine zero military in a particular space, so long as that space was protected by an impenetrable chain of fortresses controlled by the United States.

The Japanese Government, for its part, also did not see the Constitution as leaving the state without military protection; rather it assumed that this protection would now be the responsibility of the United States. Then in 1950, with the beginning of the Korean War, The Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP) ordered the Japanese Government to form a paramilitary “Police Reserve”, which was the seed out of which the present Self-Defense Forces eventually grew. In 1952, when the Peace Treaty was signed and Japan again became an independent country, the Japan–U.S. Security Treaty was stipulated as a condition (you want independence, you accept the U.S. bases and a subordinate position within the alliance), and has remained in effect to this day. So the experiment proposed in the Constitution, that Japan abandon the method of protecting national security with military force and instead seek to protect itself with peace diplomacy, has never been attempted.

But there is a third major actor in the story: the Japanese public. At the time the Constitution was proposed, opinion polls showed that it was supported by 85% of the people. Huge rallies were held to celebrate it, and the newspapers were filled with favorable letters. No one could have predicted this in, say, 1944. Everything written about Japan up to the end of the war saw Japanese society as militaristic to the core. Some observers could find hardly anything in it besides Bushido, the alleged samurai spirit. Partly this was a failure of these observers to look closely enough, and showed their inability to distinguish culture from government-imposed ideology. Still I think this counts as one of the great acts of collective will in history, in which a people fully mobilized for war makes a decision to turn about 180 degrees and strike out in a new direction.

The Japanese Government never liked the Peace Constitution, and the U.S. Government very soon changed its mind about it. As the Cold War began and the U.S. decided it would prefer to have Japan not as a weakened ex-enemy but as a rearmed anti-Soviet ally, U.S. Occupation policy flip-flopped and there began what is known in Japan as the Reverse Course, one element of which was to put pressure on Japan to ignore its Constitution and rearm. With all this opposition, why is Article 9 still there? The answer is, public support. The Government has long wanted to amend it, but so far (as of spring, 2010) has not been able to muster the public opinion to do so. Failing this, it has resorted to the technique called “amendment by interpretation.” Thus the government interprets Article 9 as not ruling out self-defense, and so the Self-Defense Forces have grown up to become the third largest military force in the world (measured not by number of troops but by military expenditures and equipment).

So looked at objectively, the Peace Constitution seems perfectly hypocritical. Article 9 rules out war, threat of war, and preparation for war, but the Self-Defense Forces are fully equipped with artillery, tanks, warships, attack aircraft, missiles, what have you. And under the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty the U.S. has made Japan, and especially Okinawa, into a fortress from which it has carried out wars in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq, and “special operations” in many other countries.

Furthermore, in the case of many of the supporters of Article 9, their support can also be said to be hypocritical. That is, public opinion polls that ask, Do you support A) Article 9, B) the Self Defense Forces, C) The Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, D) U.S. bases in Japan and Okinawa? find many people who answer “yes” to all four. This is by no means a position supporting Article 9. The best to be said for it is that it may be clever pragmatism, if you believe military protection is necessary, to get it done by someone else (the U.S.) or, if you believe a domestic military force is necessary, to keep it in a limbo of unconstitutionality so that it won’t become arrogant and domineering as the Imperial Army did before 1945.

But as a peace proposal, wouldn’t it be best to dismiss Article 9 altogether? There remain strong reasons not to. For the remarkable thing is that, even enveloped in these layers of hypocrisy, Article 9 has had powerful effects. Consider:

1) Despite all the contradictions surrounding Article 9, it remains a fact that in the more than six decades since it was adopted, no human being has been killed under the authority of the right of belligerency of the Japanese state. This is an extraordinary record, which no one could have predicted before 1945 following half a century during which Japan was almost continuously at war. And this is of course the principal intention of Article 9: no more killing. As long as this record continues, Article 9 is still in effect.

2) Within Japanese society there has been formed a body of Article 9 believers, people who, insofar as they oppose both the Self Defense Forces (as unconstitutional) and the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty (as providing for the continuation of the U.S. occupation), can be said to be sincere in their belief in Article 9. This may be the largest collection of people in the world today who, when they think of “the smallest military imaginable”, immediately imagine no military at all. And in Japan generally, six decadeswithout war has produced a kind of “peace common sense”, so that even among people who wouldn’t dream of becoming political activists, not going to war is seen as most ordinary. This in contrast to countries (like my own) where every generation has its war, and everyone has friends, neighbors and relatives who have gone off to foreign countries, killed people, and returned home (or not). Whether or not one considers the ideas of this Japanese peace culture to be correct, its existence is a fact, and it does act as a peace force in the world.

3) Article 9, because of its clear and decisive language, moves the state’s “right of belligerency” from the position of axiomatic certainty into the realm of the questionable.

As a political theorist I find this extremely interesting. And this is what I would like to talk of next.

The Right of Belligerency

The last phrase of Article 9 states, “the right of belligerency of the state shall not be recognized.” What is “the right of belligerency”?

Many people seem to believe that it means the right to carry out aggressive war. That is the position long taken by Japan’s Liberal Democratic Government, which ruled from 1955 to 2009, by which it justified its “amendment by interpretation” position that even without the right of belligerency, Japan still has the right of self-defense (and therefore may establish a Self-Defense Force).

But that is not what the right of belligerency means. Under contemporary international law, there is no such thing as a “right to carry out aggressive war”. Strictly speaking a country enjoys the right of belligerency only in cases of self-defense (cf United Nations Charter, Article 2 (4), Article 51). The right of belligerency is the “right” that makes war itself legal. Black’s Law Dictionary defines “Belligerent” as “engaged in lawful war.. Put bluntly, it is the right of soldiers to kill people without this being considered murder. This killing is considered not to be murder in two senses; one, the legal sense: unless the soldier has been caught violating the laws of war (i.e by killing more civilians than necessary, looting, raping women, etc.), the soldier will not be arrested; and two, the moral sense: the soldier after doing all this killing need not feel guilty..

The right of belligerency is one part (along with police powers and judicial powers) of what Max Weber called “the right of legitimate violence”, the monopoly of which he took to be the defining characteristic of the modern state. (5) It is interesting and even remarkable that generation after generation of political scientists, many calling themselves “value free”, have accepted this definition of Weber’s, with its extraordinary value claim (“legitimate violence”), without question. Perhaps that is the power of presenting the idea as a definition. When something is defined as such-and-so, then whether it is indeed such-and-so is no longer a matter for examination but is, or at any rate seems to be, “true by definition.” In any case, doubting the right of legitimate violence is no small matter. It endangers the foundations of political science, of international law, of just war theory, of the entire international system, indeed, of the very premise of the state.

This right has resulted in what I call the Magic of the State. With this magic, the state is able to transform an act that would ordinarily horrify us – say the use of explosives to blow a human body apart – into an act that may hardly catch our attention. This has penetrated deeply into our consciousness – I confess, my own as well. If we read in the newspaper of some young man somewhere entering, say, a schoolyard and shooting down six or seven people who are strangers to him, we are horrified, depressed, and wonder what on earth had gone wrong with this person to make him commit such an act. But if we meet, say, an air force officer who is an F-16 pilot (never mind the country) for whom killing six or seven strangers is daily routine, we can easily say, “Oh, a pilot, how interesting! What’s it like up there?”

I do not understand how this Magic of the State works, psychologically. But if you ask, Why do we give this power to the state? we all know the answer. That is, the answer is written up in detail in the classics of political theory, and it is also part of the common sense of almost everybody. Actually there are two answers, which are interrelated. First, we believe that, if we give this power of legitimate violence to the state, the state will use it to protect us. If the state has this power, it will use it in such a way that the number of people who suffer violent death in the society will be reduced – not reduced to nothing, but reduced. This argument was perhaps stated most powerfully in Hobbes’ Leviathan, but if you ask almost anyone the same question you will get a version of the same answer.

Second, we believe that the state will use this power to protect what we call “our freedom”, by which we mean the sovereign independence of the state itself.

If these arguments were in fact true, they would be very powerful indeed. But while many people see them as axiomatic, they are not, in fact, axioms. Strictly speaking, they are hypotheses: if you do X, result Y will follow. But whether result Y really does follow can only be seen in the event.

From this perspective, the 20th century can be seen as a 100-year experiment to test these hypotheses. At the beginning of the century there were 55 sovereign states in the world; at the end there were 193. This massive change was in large part driven by the belief in these hypotheses: that if we organize ourselves into states, each with a monopoly of legitimate violence within its territory, we will be relatively safe and relatively free, and the level of violence will go down.

Well, at the end of the century the results are in, and the results are disastrous. In no 100–year period in human history have so many people suffered violent deaths. And who was the big killer? Not the Mafia. Not drug traffickers. Not jealous husbands or crazy serial killers. It was, of course, the state. If we accept the statistics compiled by R.J. Rummel in his Death By Government, in the 20th century the state killed something more than 200 million people. (6) We should not be surprised at this: we gave it a license to kill, and it used it. And of course by far the greatest number of those it killed were not soldiers, but civilians. Again we should not be surprised. Civilians are much easier to kill than soldiers (they don’t know how to take cover, and they don’t shoot back). But the surprising statistic is this: by far the greatest number of those killed were not foreigners, but each state’s own citizens. (7) If the greater number were foreigners then we could at least say that the state has been struggling to keep its original promise of keeping its citizens safe and free. But it seems that this is not so. True, Rummel’s statistics may be skewed by the fact that he includes the Nazi regime’s extermination of Jews as a government killing its own people, and also includes such things as starvation of farmers resulting from government action in the USSR and China, neither of which are military actions strictly speaking. But one could reduce his figures by half or more and the point would remain the same: the state is the big killer and many of its victims are its own people. If this still seems unbelievable, it can be made more believable by a glance through the world news section of any newspaper, where it will be seen that most of the wars going on in the world are between states and some section of their own people. In fact many of the military organizations in the world have virtually no other experience, and no other purpose. This is the dark secret hidden behind the state’s claim to protect its citizens. The primal war of the state is the war the state fights against its people to found and to maintain itself. Its monopoly of legitimate violence is established by violence and preserved by violence.

Gandhi and the Violent State

I understand that for me to attempt to speak about Gandhi is foolhardy. Millions of words have been written about this man, most by people who know far more about him than I do. As a means to mitigate this foolhardiness, what I propose to do is not to offer an analysis, but to attempt to tell a story. The struggle between rival analyses is a zero-sum game; one seeks to prove one’s own analysis to be correct by showing that the other analyses are wrong. But it is the characteristic of a story that it can admit of many tellings, each of which will unfold differently depending on the perspective of the teller. My perspective is that of one who spent many years teaching western political theory in a country whose constitution denies one of the foundation stones of western political theory, that a state without the right of belligerency is no state at all. From this contradictory and therefore rather awkward standpoint, perhaps I may be able to tell this story in a manner somewhat different from the way it has been told by others, without in the least denying the validity of the other renderings. I will tentatively title the story, “Gandhian Non-Violence and the Founding of the Sovereign State of India.”

I will take as my texts Machiavelli’s The Prince and his Discourses on Livy. I do this partly to protect myself from the accusation of being a dreamer who is ignorant of the rigors of realpolitik, but mostly because Machiavelli is the premier political theorist on the subject of founding. This is usually forgotten, or obscured by Machiavelli’s reputation as the theorist of “the end justifies the means.” But the principal message of his work is that the founding of a new state or the restoration of an old one is almost impossible except under the leadership of one man (I use the word “man” advisedly), who he called “the prince” and who modern political scientists would call the charismatic leader. Seen from this standpoint one could think of the 20th century as Machiavelli’s century, for never have so many new states been founded in such a short time, and one would be hard pressed to think of many of these new states that do not have the name of such a leader attached to their founding. Think of Ataturk, Lenin, Nasser, Sukarno, Kenyatta, Senghor, Nkrumah, Mao, U Nu, Ho Chi Minh, Tito, Kim Il Sung, Castro, to mention only some of the more prominent figures. And in the case of India, the name of course is Gandhi.

Nicolo Machiavelli

With the exception of Gandhi, all of these figures match pretty well with Machiavelli’s model, set out in The Prince, of political brilliance and political ruthlessness. Gandhi alone seems out of place. The difference can be brought into focus by recalling Machiavelli’s words on the dilemma posed by the radical restoration of a state, which can also be taken as the dilemma of founding.

And as the reformation of the political condition of a state presupposes a good man, whilst the making of himself prince of a republic by violence naturally presupposes a bad one, it will consequently be exceedingly rare that a good man should be found willing to employ wicked means to become prince, even though his final object be good; or that a bad man, after having become prince, should be willing to labor for good ends, and that it should enter his mind to use for good purposes that authority which he has acquired by evil means. (8)

Much could be, and has been, written about the varying degrees of success or lack thereof with which the above mentioned founders were able to overcome the dilemma between what they (believed they) had to do in order to make themselves the “princes” of their new and/or revolutionary states, and what kind of government was needed after the convulsion of founding/revolution was over. But for Gandhi, the dilemma was reversed. That is, while his denial of Machiavelli was complete, it was so complete that the dilemma of founding came back to haunt him, standing, as it were, on its head. For Gandhi discovered that it was possible – or rather, with the immense power of his will, he made it possible – to lead India from colonial subjection to independence without committing the crimes of violence that Machiavelli believed inescapable. But the founding of independent India eventually led, with its success, to the founding of yet another violent state.

Gandhi was seen as the Father of his Country, or of his Nation, but it was entirely against his nature to become the Father of the State, or to serve as its Prince. As the transfer of power from British to Indian hands approached, Gandhi backed off, taking no post in the government, or in the Constituent Assembly. He often expressed his deep disappointment at the turn things were taking, and even made an alternative constitutional proposal (of which, more below), but he was realistic enough to know that it was not going to be adopted. Thus for him the Machiavellian dilemma must be stated the other way around: how is it possible for a person who has led a nation to independence using only good means, to adopt, after independence has been achieved, the wicked means used by the violent state? Gandhi was constitutionally incapable of making this transformation, and while he remained the advisor and father figure for many government leaders, the state itself had no place for him.

Satyagraha and the Right of Belligerency

Max Weber defined the state as the social organization claiming a monopoly of legitimate violence, but that monopoly has not been fully accepted. Members of national liberation and revolutionary movements have also granted themselves the right of belligerency in many cases. In a sense this is simply an extension of the logic of the right of belligerency of the state: since these movements aim to become the state where there is none or to seize control of the state where it exists, and are usually infused with the faith that they will surely succeed. From that assumed legitimacy they simply apply the state’s right of belligerency to themselves retroactively. And this right is to some extent recognized in international law. For example the 1948 Geneva Convention on the treatment of prisoners of war stipulates that members of “organized resistance movements” must, when captured, be given prisoner of war status if they meet certain conditions. Being granted prisoner of war status means that the killing they have been engaging in is not murder but war, justified by the right of belligerency.

Satyagraha specifically refuses to make this claim. If I understand the notion correctly, the satyagratis do not arrogate to themselves the right to kill, but rather consider all killing to be murder. The effect of this on the soldiers on the other side is usually described in ethical and religious terms, but it also can be described in terms of just war theory. One of the arguments used to explain why just war is indeed just, that is, not criminal behavior, is that the people on the other side who you are trying to kill are also trying to kill you. Both sides are in the same game, and the fact that I am trying to kill you means I have no complaint if instead you kill me. The logic is similar to that of rough contact sports: the boxer can treat his opponent in a way that would get him arrested outside the ring, because his opponent is also a boxer and has accepted the rigors and dangers of boxing which, as we all know, include the danger of death. Thus the knocked-out boxer, like the shot-down soldier, is only suffering the same fate that he had been trying to bring to the other. Whatever one thinks about this logic, it is in fact at the heart of just war theory, both in its international law form and in the form it takes in the consciences of individual soldiers.

Satyagraha spoils this game. By renouncing the right to attempt to kill the enemy, satyagraha denies to the other side its primary justification to use violence. By the very rules of just war theory, what the soldiers are doing cannot be just war, and therefore begins to look like criminal behavior. This puts terrific pressure on both the individual soldiers and their commanders. One imagines them longing for just one act of violence from the satyagrahis, so the situation can be fitted back into their preconceived notion of how war is carried out. This may help to explain Gandhi’s controversial decision to call off the anti-Rowlett Bill satyagraha campaign after some violence broke out on the anti-government side. For the issue is not one of degree: reducing the amount of violence as much as possible. If any violence at all is used by the satyagraha side this restores the logic of the just war game, and thus restores the legitimacy of the violence used by the other side. “Murder” again becomes “war”.

Gandhi in 1930 satyagraha

(Though it is not a central purpose of this essay to make the argument that “satyagraha works”, perhaps I should give a brief response here to the objection that always crops up at this point, that satyagraha was successful in India only because it was used against the conscientious British. Gandhi’s own response to this argument was to remind the doubter that it had also been effective against the apartheid regime in South Africa, which was about as racist a system as the world has ever known. An argument he did not make, but which could be made by someone not in his position, is that the image of the “conscientious British” fades if you look at such details of British rule in India as the Amritsar Massacre, the Crawling Order, or the way that satyagratis were sometimes beaten mercilessly long after they had fallen to the ground. Also the argument that “it never would have worked against Hitler” is counterfactual: as Hannah Arendt and others have pointed out, there were cases of successful non-violent resistance against Hitler’s regime. (9) But finally, it must be pointed out that to say that for satyagraha to be taken seriously it must be shown to be successful 100% of the time is to ask the impossible. In the world of real politics, no method, including the method of military action, is successful 100% of the time. After all, in war for every winner there is a loser, which gives war the very poor success rate of 50%.

Gandhi and the Violent State

But while Gandhi was adamant about demanding thorough non-violence from the independence movement, was he equally adamant about demanding it from the state? Many argue that he was not. Partly this argument grows out of a kind of denial by deduction: just as many people say of Japan’s Article 9, “It would be absurd for a country’s constitution to renounce war, therefore Article 9 does not say that”, so people say of Gandhi, “It would be absurd for Gandhi to deny military power to the state, therefore Gandhi never said that.” But it is also true that Gandhi, over the period of his long life, occasionally made statements that people can use to support the idea that he approved of state military. Most famously,

I would rather have India resort to arms in order to defend her honor than that she should in a cowardly manner become or remain a helpless witness to her own dishonour. (10)

Or again,

The simple fact is that Pakistan has invaded Kashmir. Units of the Indian army have gone to Kashmir but not to invade Kashmir. They have been sent on the express invitation of the Maharaja and Sheikh Abdullah. (11)

On the other hand,

If I am given the charge of the Government I would follow a different path, because I have no military and police force under me. (12)

It would be useless to try to resolve the question of which is Gandhi’s real opinion by the method of lining up quotations, because any number of quotations could be found to support either side. Should we conclude that Gandhi, despite his reputed will of iron, couldn’t make up his mind? I would suggest that one way of solving the apparent contradiction would be to compare Gandhi with another man who moved between the ideal politics of the “country of his dreams” and the “slum politics” of the actual state where he lived, Thomas More. You will remember that More wrote his Utopia as fiction, in which the character Raphael Hythloday, having traveled to the island of Utopia, relates what he has seen there to More and his friends. In the story, More asks Hythloday (the name means “dispenser of nonsense”) why, given the wisdom he has attained from visiting a perfectly ordered polity, he does not offer his services as advisor to the King. Hythloday answers that in the king’s chambers no one would listen to him: kings do not want to hear the kind of advice he could give. More responds by saying, yes, of course kings do not want to hear about the politics of Utopia itself, but even so Hythloday could still be of service if he became a royal counselor and that which you cannot turn to good, so order that it be not very bad. (13)

Hythloday answers that if he were to attempt this, the only result would be that he would eventually be killed. (14)

When More wrote these lines, he was debating in his mind whether to accept the offer of Henry VIII to make him Chancellor of England. He eventually accepted the offer, and we can assume that he did so knowing full well that he was not going to persuade the King to adopt any utopian policies. Presumably he hoped he would be able to influence the King’s policies so as to be “not very bad.” But in the end Hythloday’s prophecy (that is, More’s own prophecy) came true: when More as a man of conscience could no longer support Henry’s policies, he was tried, convicted of high treason, and beheaded.

Like More, Gandhi was a visionary who had “seen Utopia”, or as he called it, Ramarajya. Like More, he was also highly skilled in actual, day-to-day politics, though he was far more successful than More in reshaping actual politics on the model of the ideal – More accepted the Chancellorship of a violent state, and attempted nothing like satyagraha. Thus Gandhi necessarily recognized two ethics. On the one hand, as he repeatedly said, the ethic he lived by was that of ahimsa, truth, and Ramarajya. But this did not mean that he had to become blind to any other sort of distinction. Even in the slum world of politics, Gandhi preferred action to inaction, bravery to cowardice, standing up for one’s principles to running away. Even when he disagreed with their methods, he could appreciate the efforts of his friends and disciples in the new Indian Government, when they could not turn matters entirely to good, to so order them that they be not very bad. And his absolute pacifism did not mean that he had abandoned his capacity for judgment, and was incapable of appreciating the distinction between aggressive and defensive war, or war that follows the laws of war and war that takes the form of massacre, rape and pillage. Taking a position of absolute pacifism does not mean that one must, as Orwell put it, “take the sterile and dishonest position of pretending that in every war both sides are exactly the same and it makes no difference who wins.” (15) (Whether Gandhi was correct in his judgment that the Pakistani forces advancing in Kashmir in 1947 were invaders and the Indian Army forces were not is a question I shall not attempt to answer. The point that matters here is that, given the information he had, that is the judgment he made.)

But saying just this fails to account for the agony and disappointment Gandhi felt in his final years. For unlike More, who never imagined his utopia could be established in actually existing England, Gandhi, who had experienced a series of political successes such as More never dreamed of, had entertained an astounding hope.

So far I had been praying to God that He may keep me alive for 125 years so that I could render some more service to the country. And I can rest in peace only when the Kingdom of God, Ramarajya, prevails in the country. Then only can I say that India has truly become independent. But today it has become a mere dream. . . .What can a man like me do under these circumstances? If this situation cannot be improved, my heart cries out and prays to God, that He should take me away immediately. Why should I remain a witness to these things? (16)

By “these things” Gandhi is of course mainly referring to the terrible cruelties that accompanied partition. But his disappointment also extended to the ease with which the greatest non-violent force the world had ever known, the Indian National Congress, metamorphosed, with independence, into the builder of a “normal” violent state. To repeat the sentence quoted above, in its full context:

If I am given the charge of the Government I would follow a different path, because I have no military and police force under me. But I am the only one to follow that path. Who would follow me? (17)

Gandhi’s Constitution for a Free India

At the time that the Constituent Assembly was sanctifying Gandhi as the Father of the Nation and writing a constitution for India as an ordinary violent state, Gandhi himself had a different constitutional proposal, from which the Constituent Assembly averted its eyes. The most systematic statement of this proposal was compiled by Shriman Narayan Agarwal, from various statements Gandhi had made, into the book Gandhian Constitution for Free India. (18) It is remarkable that this book, which should stand alongside the works of More, Morris, Owen, Fourier, and Kropotkin as a major proposal for an ideal polity, is out of print, difficult to find, and generally brushed aside in works on Gandhi. Perhaps this is because it is so radical that, for the common-sense mind, it is unthinkable, which means that people generally will do their best not to think about it.

The essence of the proposal is contained in the following simple statement, written in 1947, just before independence:

Independence must begin at the bottom. Thus every village will be a republic or Panchayat with full powers. (19)

Let us begin by taking these simple sentences seriously, as written. Evidently this is not so easy to do. For the sentences, as written, are outrageous. Admirers of Gandhi find it difficult or inconvenient to believe that he ever said such a thing, and sometimes solve the problem by having him say something else. In his Gandhi’s Political Philosophy, Bikhu Parekh has Gandhi proposing a polity made up of “self-determining village communities.” (20) But Gandhi said “republics”. Let us assume that he chose this word carefully, in full awareness of what it implies. A republic is not a “community” or an “administrative unit”; it is a sovereign state. Now, Gandhi was fond of saying that India had 700,000 villages. Taken literally, he is proposing that the number of sovereign states in the world be increased from the something around 76 that it was in 1947, to 700,076. Imagine, if they all sent ambassadors to the United Nations, not only would there be no hall or even stadium large enough to hold them, it would have amounted to an almost 10% increase in the population of New York City.

But Gandhi’s proposal was not a scheme to pack the UN. The 700,000 village republics would be joined in a federation. Village Panchayat presidents would join together to form a Taluka Panchayat (about 20 villages), the presidents of these would form a District Panchayat, the presidents of the District Panchayats would form a Provincial Panchayat, and again the presidents of these would constitute the all–India Panchayat. Presumably it would be this all-India Panchayat that would send a representative to the UN General Assembly.

But this does not mean that sovereignty is actually at the center. Many commentators have concluded that Gandhi accepted the state after all. But as Gandhi and Agarwal describe it, the organization above the Village Panchayat level is analogous to the United Nations – an international body with considerable authority but without sovereignty, and without the right to infringe on the sovereignty of its member states. Agarwal does not use the word “sovereignty”, and what he writes on this point is sometimes ambiguous, but in the following passage he makes his meaning clear enough:

The functions of these higher bodies shall be advisory and not mandatory; they shall guide, advise and supervise, not command the lower Panchayat. (21)

In the dominant western theory of the state, sovereignty rests with the people, but in practice this rarely means more than the right to participate in periodic elections. The Gandhian constitution gives popular sovereignty a different structure by placing it not with that vague entity “the people” but by clearly locating it in a multiplicity of specific organizations: the villages. Here popular sovereignty is not the myth by which state power is legitimized, but something concretely built in to the structure of political society. It is not something that slips out of the people’s hands and reappears in the capital city; it is right there in the village where the people live, and where they can hold on to it.

An interesting theoretical project would be to compare these ideas of Gandhi with those of what Teodor Shanin has called the Late Marx. Basing his case mainly on the research of the Japanese historian Wada Haruki, Shanin has argued that in his last years Marx was persuaded by the Narodnik position that it could be possible for Russian revolutionaries to build their new society on the basis of the “primitive communism” that existed in the village communities, and thus avoid going through the horrors of industrialization under the violent state. (22) It is surely one of the great ironies and tragedies of history that Lenin and his fellow Bolsheviks never learned that their great master had come to this view (the letters in which Marx developed these notions were suppressed by hardline marxists and came to light only in 1924). But this is not the place to pursue this question further.

The question that matters in this essay is this: would the all–India Panchayat have a violent arm? Gandhi’s answer is, I believe, a clear “no”, but Agarwal is more ambivalent. On the one hand he writes, as quoted above, that its powers shall be “advisory and not mandatory”, and shall not include the power to command. On the other hand in The Gandhian Plan of Economic Development for India, the companion piece to his work on the Constitution, Agarwal writes that under Gandhian organization, “There shall be a drastic reduction of Military expenditure, so as to bring it down to at least one-half of the present scale.” (23) This is arguably the worst possible solution to the Smallest Army Imaginable puzzle. A military half the size of what the Armed Forces of India was at that time would still be a considerable force, but the number of military organizations in the world against which it could hold its own would be drastically reduced. Calling for the reduction of a military organization to a size “no greater than what is absolutely necessary” is deceptive, because once a war starts what is “absolutely necessary” is to overcome your enemy and emerge victorious. By giving India a “small” military Agarwal is giving up the advantage of the satyagraha strategy, without establishing a force big enough to be effective militarily.

But aside from the strategic disadvantage, raising and supporting a military would be impossible given the structure of the panchayat federation. The issue is not whether the military should be large or small, but whether the All-India Panchayat would have the state’s right of belligerency. A body with only advisory powers standing over a collectivity of village republics would not have the power to recruit an army, much less to command it. And there can be no military without the power to command. Command, and the power to punish disobedience to command, is the essence of military organization. When you dispatch a body of troops carrying weapons and trained to use them, it is not to give advice.

Panchayat in a contemporary village

If the All-India Panchayat does not have the power of command, then the people, unlike the people of most countries, will not have been trained in obedience to central command. Consider at what great disadvantage this would put any invader. In most wars, if the central command – political and military – is seized, the war is won, and the people, or most of them, having had long training in obeying the previous authority, will be ready to accept the new one. But how would it be possible to conquer a territory containing 700,000 republics? And remember, the people of each of these republics will have had training in Satyagraha. What invader would ever be so foolish as to try and catch hold of this porcupine?

It is too bad that Gandhi didn’t have the expression “right of belligerency” as part of his working vocabulary; had he used it, it might have made his meaning more clear. But the result is that his constitutional proposal and Japan’s Peace Constitution complement each other in an interesting way. Gandhi believed, as do mainstream politicians and political scientists everywhere, that the state is by nature a violent organization:

The state represents violence in a concentrated and organized form. The individual has a soul, but the State is a soulless machine, it can never be weaned from violence to which it owes its very existence. (24)

Gandhi’s solution is to propose a political structure that is not a state, is radically different from the state, and which represents “peace in a concentrated and organized form.” One cannot find in his proposal a renunciation of war as clear and eloquent as Japan’s Article 9; rather in his proposed constitution the tendency toward and the possibility of war are excluded from the polity by its very structure. While I began this essay by inviting readers to imagine a state without a military, Gandhi’s Constitution goes much further, imagining a polity from which “legitimate violence” in all its aspects, including police coercion and coercive punishment, has been built out altogether. On the other hand while Japan’s Article 9 is ringing and eloquent, it is attached to a constitution that founds a very ordinary state, which with its elaborate police organization and prison system backed by the death penalty is an example of the very “soulless machine” that “represents violence in a concentrated and organized form.” Perhaps this can help to explain why the rulers of the Japanese state have been struggling to liberate themselves from the strictures of Article 9 for more than half a century.

Gandhi and the Art of the Possible

I wrote above that it is strange that while plans for ideal polities such as those of More, Morris, and others are well known and still in print in many editions, Gandhi’s proposal is out of print and virtually unknown outside of India. There are many possible reasons for this. Gandhi’s comments on the subject are cursory, and even Agarwal’s book lacks the meticulous detail of the other utopians, nor is it written in the form of an entertaining novel as are Utopia or News from Nowhere. There may, however, be another reason. More wrote without the slightest inkling of a hope that the plan of Utopia could be realized in the England of his day, and in his political life, despite having extraordinary skills as a politician, made no effort in that direction. Morris’ novel is placed a millennium in the future, and ends in a deep note of sadness when the protagonist is returned to the (19th Century) present. Fourier’s phalanstere is grounded in crank science. We don’t think of these models as something that might come into being now or might have come into being then. Today the works of these and other utopian writers are read for their theoretical interest, which means that there is no particular reason to go out of one’s way to dismiss them as “unrealistic”: they are non-threatening.

Gandhi, on the other hand, seriously believed that his federation of Panchayat republics was a real possibility for the subcontinent of India if the leaders of The Congress could only gather the political will to make it so, and was deeply disappointed when they did not. It was never his intention to write a utopian proposal “of theoretical interest”, but to propose a working constitution for India. Thus his plan did not presuppose some radical transformation in human nature, or massive leap in consciousness to a level never before known in history. Rather it was rooted in the reality of the historic Indian village. (Here Gandhi was influenced by Henry Sumner Maine’s Village Communities in the East and West (25), which book was in turn influenced by Maine’s many years living in India) As such, it probably would have entailed far less change in consciousness and custom than did the founding of the Indian State. Moreover, the puzzle that plagues all utopian proposals – by what agency of change could such a thing ever be brought about? – had in this case been answered. The agency would be Gandhi himself, or more accurately, the Gandhi Phenomenon: Gandhi and his supporters in The Congress and in the public. For it had already been proved to the world many times over that, for reasons no one has ever been able fully to explain, this combination of The Congress of India with Gandhi at its head had the power to transform manifest impossibilities into possibilities, and then into accomplished facts. For Gandhi, politics as The Art of the Possible took on a different meaning. Under his leadership, phenomena hitherto dismissed as impossible in the political world were brought into being. Again and again, people who mocked his “unrealism” were forced to eat crow. Surely that is why his constitutional proposal inspires a feeling of unease that other utopian proposals do not. For while it is difficult to imagine his constitution being realized in India today (except in a few scattered ashrams), it was a possibility then, or would have been had the leaders of The Congress not deserted Gandhi and opted for an ordinary (violent) state.

But if the founding of the Gandhian Constitution is hardly imaginable now, why does it still make us feel uncomfortable? The very fact that it was a manifest possibility in the recent past upsets an axiom of our political belief: that the (violent) nation state is inevitable and necessary; that it is not to be doubted; that it has no alternative; that the establishment of the state, including the Indian state, was not a human choice, but a Destiny (as in “tryst with . . .”). The Gandhian Constitution forces one to realize that, at that time, it was a choice. It is poignant to think that this shabby, ignored little used book on my desk outlines India’s Road Not Taken.

Hobbesian War, Radical Peace

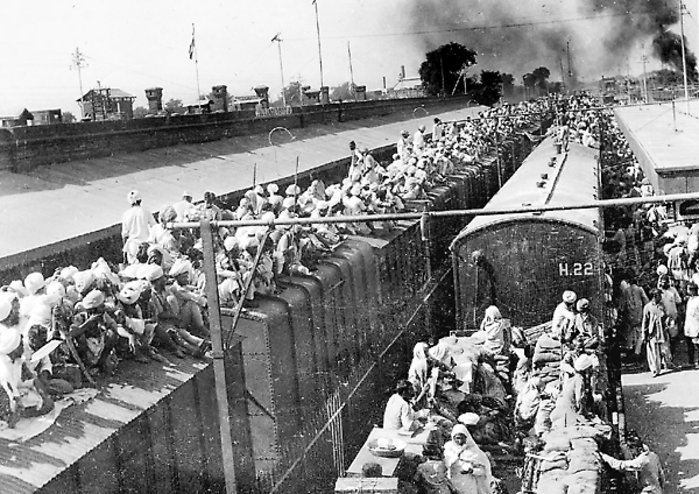

But enough of speculating about what might have happened; it is time to turn our attention back to what did happen. And what did happen was that the leadership in both The Congress and the Muslim League opted for the modern state structure, resulting directly, as happens so often when the modern state is imposed on a region artificially unified by colonial power, in a demand for partition and horrific communal bloodshed. Gandhi was heartbroken. And when the Congress did accept partition, he began speaking obsessively about his death. “What sin,” he asked Patel, “must I have committed that He should have kept me alive to witness these horrors?” (26)

India-Pakistan partition of 1947

Gandhi had more than one reason to be horrified. For aside from the simple awfulness of the communal violence itself, it also threatened to bring his political dreams to a catastrophic end. Communal violence was rapidly reducing Indian society to a Hobbesian State of Nature, a condition for which, Hobbes had so persuasively argued, state domination is the only solution. Of course communal violence is not, strictly speaking, a War of Each Against All, but it is close enough to pure chaos to make the organized and “legitimate” violence of the police and army look like peace by comparison. And in fact this is how the state did react, sending police and army out to stop the violence with greater violence. Nehru even threatened to bomb Bihar. (27) Faced with the stark fact of communal violence, Gandhi’s talk of a non-violent state began to seem utter fluff.

Seen in this context what Gandhi did next was to launch one of the most extraordinary political actions ever conceived. If the fact of communal violence provided overwhelming justification for the violent state, Gandhi began a one-man campaign to change the fact. Walking from village to village in Noakhali, setting up household in the most riot-torn area of Calcutta, walking again from district to district in rioting Delhi, utterly heedless to the danger to his life at every moment, he poured all the powers of his being into persuading people to stop the killing. And he met with both bitter setbacks and stunning successes. Viceroy Mountbatten, in his note congratulating Gandhi’s “miraculous” success in bringing peace to Calcutta, showed that he partly understood what was at stake, but tried to muddle it by seeing Gandhi as a one-man army: “In the Punjab we have 55 thousand soldiers and large-scale rioting on our hands. In Bengal our forces consist of one man, and there is no rioting. As a serving officer, as well as an administrator, may I be allowed to pay my tribute to the one-man boundary force!” (28) But Gandhi was no “boundary force”, nor was he seeking only to establish peace where the soldiers could not: he was determined to establish a kind of peace that soldiers can never achieve, however successful they may be in stopping overt rioting. In the written pledge that ended his last fast in Delhi, he even insisted that the difference be included as a clause: “We give the assurance that all these things will be done by our personal efforts and not with the help of the police or the military.” (29) Thus when he walked from village to village, from district to district, he was struggling to refute the Hobbesian world view not by making arguments against it but by creating facts that contradict it, creating, that is, a peace that did not depend upon the violent state for its enforcement. Of course, such action is subversive, for actually to create such a peace would be to eliminate the need for the violent state. And that was how Gandhi understood it: his attack on the rioting was also aimed at undermining the “necessity” for state military dominance that the rioting seemed to produce. As he put it in Calcutta,

How nice it looks when soldiers march in step! I am opposed to military power, for it results in killing human beings. There is only one way to vanquish military power, and it is this. (30)

And while he was not able to bring this peace to all of India – without the support of his party, how could he? – his local successes showed that in principle it could be done. Once again, he was transforming impossibilities into possibilities, in this case demonstrating the possibility, even in the most bitterly violent of situations, of establishing a non-Hobbesian peace, what could be called radical peace. At the same time he was founding, village by village, the essence of his Panchayat Raj Constitution. It was while he was in the midst of this activity that he was assassinated.

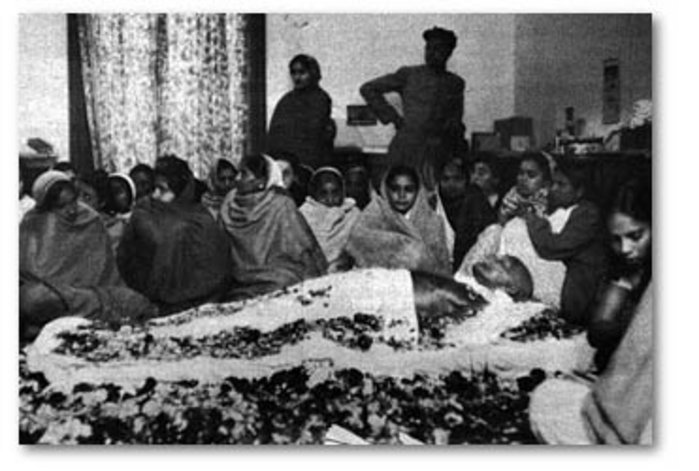

Gandhi in death

The Other Constitution

On the morning of January 30, 1948, Acharya Jugal Kishore, then General Secretary of the A.I.C.C. (All-India Congress Committee), was handed a proposal for a new constitution for the Congress, which Gandhi had just completed. According to his secretary, Pyarelal, Gandhi, though exhausted, had stayed up late the night before to get it done. He was behaving as though he almost knew what was coming. It was this same morning, January 30, when he stopped Manubehn from preparing some medicine for the evening, saying, “Who knows, what is going to happen before nightfall, or even whether I shall be alive. If at night I am still alive you can easily prepare some then.” (31)

The document was a bombshell, or would have been if Nathuram Godse had not acted to defuse it. Despairing at the sight of what its attachment to the state was doing to his beloved Congress, and despairing of the state’s capacity to reform, Gandhi proposed that the Congress withdraw from the state altogether, and return to the villages.

Though split into two, India having attained political independence through means devised by the Indian National Congress, the Congress in its present shape and form, i.e., as a propaganda vehicle and parliamentary machine, has outlived its use. India has still to attain social, moral and economic independence in terms of its seven hundred thousand villages, as distinguished from its cities and towns. The struggle for the ascendancy of civil over military power is bound to take place in India’s progress towards its democratic goal. It [the Congress] must be kept out of unhealthy competition with political parties and communal bodies. For these and other reasons, the A.I.C.C. resolves to disband the existing Congress organization and flower into a Lok Sevak Sangh [people’s service organization] under the following rules . . . . (32)

There follows a set of rules that in effect follows Gandhi’s long-cherished constitutional model, a tiered system with five-person panchayats at the base, elected second-grade leaders over them, and so on, expanded until it covers all of India. Gandhi’s idea seems to have been that if panchayat raj could not be established in place of the state, perhaps it could be established within the state. From that position it could devote itself to “constructive work” – building the concrete economic and social base for autonomy in the villages – and at the same time “struggle for the ascendancy of civil over [state] military power.”

Taken as a serious political proposal, which it surely was, the idea is stunning. Imagine what would have happened if it had been carried out as Gandhi conceived it. If the Congress, which at that time was almost synonymous with India’s political class, had vacated the government and gone back to the villages, what a massive shift in power, not laterally but from top to bottom, that would have been. It would have brought about a revolution of a sort never before seen – not the people at the bottom rising up and seizing the state, but the people who have just seized the state, walking away from it and joining the people at the bottom. Such a move would not, of course, be without its dangers – the danger, for example, that the offices vacated by Congress members might be quickly occupied by generals and colonels (Gandhi’s proposal doesn’t say what should be done with the military, except that it should be struggled against). But as a revolutionary model, in which the revolutionary organization seeks to spread itself into every nook and cranny of society while deliberately not seizing the state, it anticipates by four decades (though there are important differences) the notion of the “self-limiting revolution” as practiced in Poland and other East European countries in the 1980s.

It is not likely that many members of the Congress would have found the proposal attractive. But in any case, the question was soon moot. Within hours of the time the proposal was handed to the A.I.C.C. chairman, its author was dead.

Founding and Sacrifice

Sacrifice: The slaughter of an animal or a person (often including the subsequent consumption of it by fire) as an offering to a God or a deity.

On the morning of the penultimate day of his life, Gandhi was visited by Indira Gandhi and her son Rajiv. It was a remarkable last meeting of India’s three great modern assassin victims. Rajiv, then four, began wrapping flowers around Gandhi’s bare ankles and feet, but the old man scolded him and pulled his ear, saying, “ You must not do that. One only puts flowers round dead people’s feet.” (33) Are children sometimes clairvoyant?

By all accounts, there was something strange about Gandhi’s assassination. There is the fact that even though, a full ten days earlier, the police had arrested one of the conspirators when he exploded a bomb at Gandhi’s prayer meeting and the man had talked, they proceeded with remarkable lethargy, and were somehow unable to track down the others or prevent the assassin from entering the Birla House garden carrying a pistol on January 30. Robert Payne, after detailing the unusual inertia of the police, concluded, “[t]here were people in high places who acted as though they had no business interfering with a conspiracy which must be permitted to take its course,” (34) and to describe the phenomenon coined the expression: “permissive assassination”. The person in the highest place in the government department most responsible for Gandhi’s safety was Home Minister Sardar Patel, a man who had been one of Gandhi’s most devoted disciples, and who as the “Iron Man” of the new government most sharply disagreed with him. After the assassination Patel was accused of “inefficiency”, and his colleague Maulana Azad believed that it was this that caused his heart attack two months later, which eventually led to his death. (35)

It is not my purpose here to go through all the evidence attesting to the strangeness of the assassination; that has been done elsewhere. Ashis Nandy, in his elegant essay on the subject, argued that it was Gandhi’s challenge to the deep structure of mainstream Hinduism that made him intolerable to a large part of that community, even including those who, with political correctness, continued to hail him as Mahatma and Father of the Nation. The assassin Nathuram Godse, Nandy says, far from being a marginal outsider, “was a representative of the centre of the society.” (36) I have no quarrel with this thesis, but only wish to point out that it does not fully account for the timing of the assassination, namely, the moment at which the State was being newly founded, and while the Constitution was still being debated. If there was a conflict between Gandhi and middle class Hinduism on the issue of that class’s domination of society and on the issue of the role and meaning of womanhood, that must have been an ongoing, if hidden, conflict going back to the 1920s or before. But if there was a conflict between the Father of the Nation and the emerging State, wouldn’t that have provoked a national crisis demanding immediate solution?

It seems that the subject of Gandhi’s death had become a public topic long before the assassination. People were shouting “Death to Gandhi!” or, when he went on his fasts to death, “Let Gandhi Die!” Bricks and stones were thrown at him. But perhaps the person most obsessed with the subject of Gandhi’s death was Gandhi himself. He continuously talked about it, sometimes in a mood of depression (“What sin have I committed that He should have kept me alive to witness all these horrors?”), sometimes enigmatically (“It might be that it would be more valuable to humanity for me to die.” (37)), sometimes as the apotheosis of his life (“ . . .if someone shot at me and I received his bullet in my bare chest without a sigh and with Rama’s name on my lips, only then should you say that I was a true Mahatma.” (38)) But not only that, it was Gandhi who forced his death on the attention of the nation by making it a public issue. When he went on one of his “fasts to death”, the last one of which he said was “directed against everybody” (39), no one doubted his perfect readiness to die if his conditions were not met. In a remarkable passage, Rajni Kothari wrote that at the end of his life Gandhi carried out three “heroic acts”: his pilgrimage through Noakhali, his “fast to death” against the government in Delhi, “and finally being shot to death by a fanatic Hindu . . . .” (40) Gandhi’s assassination is characterized as one of his acts; it is as if he had flung himself at the bullets, rather than the bullets coming to him.

Consider the situation of those who were directly engaged in the building of the new Indian State. The chief leaders among them were some of Gandhi’s closest associates and disciples. By all indications they genuinely loved him. Though he had no official position in the government they consulted with him at every opportunity and even had what amounted to cabinet meetings in his presence. At the same time he was the most maddening obstacle to their project. Again and again he made proposals and even demands that flew in the face of state-power logic: Give the whole government to the Muslim League; Remove the police and army from rioting areas; Give Pakistan its share of the national treasury, despite the war (this demand enforced by the abovementioned “fast to death”); on and on. Even if they never allowed the word “death” to escape their lips, surely they must have often found themselves wishing he would just . . . go away.

Of the Hindu middle class, Nandy wrote, “If not their conscious minds, their primitive selves were demanding his blood.” (41) The expression strikes a chord of recognition, for the most perceptive theoreticians of political founding have regularly observed that the moment of founding seems to elicit a primitive demand for blood – especially intimate blood. For Freud, founding takes place through patricide (the sons murder the father-king), for Hannah Arendt it is fratricide (Cain killed Abel, Romulus killed Remus), for Machiavelli – but let us look at Machiavelli again a bit more closely.

How would Machiavelli have read this story? One can find a clue in the way he understood the founding of the Roman Republic by the insurgent Brutus. As the story is told by Livy, after Brutus drove out the Tarquin monarchy, Brutus’s sons participated in a conspiracy to bring it back. Brutus had them condemned to death, and stood witness to their execution, his face, Livy tells us, showing both his agony as a father and his grim determination as head of state. Machiavelli judges this action as “not only useful, but necessary.” (42) He explains,

Every student of ancient history well knows that any change of government, be it from a republic to a tyranny, or from a tyranny to a republic, must necessarily be followed by some terrible punishment of the enemies of the existing state of things. And whoever makes himself tyrant of a state and does not kill Brutus, or whoever restores liberty to a state and does not immolate his sons, will not maintain himself in his position long. (43)

This is the primal political sacrifice, which Machiavelli took to be essential to the task of foundation. It is not simply a matter of purging the state of its present and potential enemies, though that may be part of it. At a deeper level, it is a matter of driving into the consciousness of the people what the state is: not only a violent institution, which will not hesitate to use violence to establish itself and to protect itself, but also one whose violence is enshrouded in the mystical cloak of sovereignty, which places the state outside the realm of human judgment, and gives its agents the authority to carry out acts that would not be permitted to ordinary human beings. Thus it will not allow itself to be interfered with by ties of friendship, love, or blood: when you act in the name of the state, you must be ready to destroy your friend, your father, your brother, or your son. For Machiavelli it is not enough simply to explain this in words. It must be acted out in bloody ritual sacrifice. And for the purposes of the sacrifice, the more intimate the victim, the better.

It will be objected that Nathuram Godse was no agent of the state, but an assassin acting outside the law, who was tried and executed by the state for his crime. Of course this is true, so for the above thesis to apply to his act it would be necessary to show at least 1) that Godse saw himself as acting in the name of the state, and 2) that there were those among the agents of the state who, if not positively demanding Gandhi’s blood, were troubled enough by his existence that they could not bring themselves to take strong measures against the one who was coming to draw that blood.

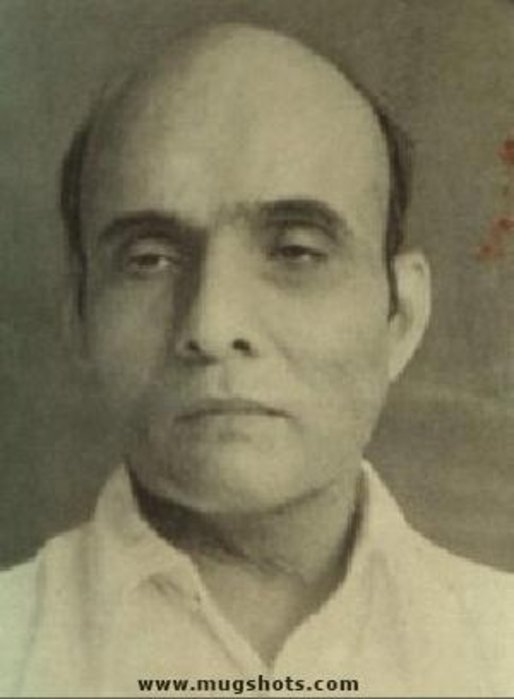

As for the first, Godse’s words are clear, and even eloquent. Godse, like all assassins, was depicted by many as a demented fanatic, but if you read his own account of his action and his reasons for it, he appears as intelligent, articulate, clear-headed, patriotic, and courageous. (According to all accounts, before shooting the Father of the Nation he put his hands together in respectful greeting; according to his own account, after the shooting he raised his hand with the pistol into the air and shouted “Police!”) Nandy insists that Godse “more than any other person” knew what he was doing. (44) Surely then, we ought to take his words seriously. In his statement in English to the court he said,

Briefly speaking, I thought to myself and foresaw that I shall be totally ruined and the only thing that I could expect from the people would be nothing but hatred and that I shall have lost all my honour even more valuable than my life, if I were for [sic] kill Gandhiji. But at the same time I felt that the Indian politics in the absence of Gandhiji would surely be practical, able to retaliate, and would be powerful with armed forces. No doubt my own future would be ruined but the nation would be saved . . . . (45)

Moreover, he said that developments after the assassination had given him “complete satisfaction” that everything had turned out just as he had expected. For example,

The problem of the State of Hyderabad which had been unnecessarily delayed and postponed has been rightly solved by our Government by the use of armed force after the demise of Gandhiji. The present Government of the remaining India is seen taking the course of practical politics. The Home Member [Patel?] is said to have expressed the view that the nation must be possessed of armies fully equipped with modern arms and fighting machinery. While giving out such expressions he does say that such a step would be in keeping with the ideals of Gandhiji. He may say so for his satisfaction. (46)

With Gandhi gone, the government was now able to arm itself without reserve, and to use its military in a “practical”, i.e. realpolitik, manner. Godse was not surprised that government spokesmen now claimed that such actions were “in keeping with the ideals of Gandhiji”; he knew that had Gandhi been still alive, they would never have been able to say such a thing. Must we not admit that, from Godse’s point of view, the assassination was a crashing success?

As for the second point, while there is no decisive evidence (only Godse held a smoking gun), there is plenty of circumstantial evidence, much of which has already been mentioned. Given the terrible double bind they had been in, the impossible contradiction between the demands of raison d’etat and the demands of their beloved leader, who can doubt that, entwined within the turmoil of mixed emotions they must have felt after the murder was done, there was also an overwhelming feeling of release? Now they could get on with the business they had set themselves, build a powerfully armed state, send the troops out against enemies domestic and foreign, transform panchayat raj into “local administration”, tell the people that Gandhi would have approved of it all, and build monuments to him, without the old crank interfering at every step.

Nathuram Godse

Machiavelli drew from the story of Brutus what he believed to be a general law of politics: if you wish to found a tyranny you must kill Brutus; if you wish to found a republic you must kill his sons. Had Machiavelli been alive to witness the events in India at the middle of the 20th century, would he not have formulated another, more fundamental, general law? That is,

If you wish to found a violent state, you must kill Gandhi.

By “violent state” I do not mean here a tyranny, or a militaristic state, or a war-mongering state. I mean a perfectly ordinary state, one that fits Max Weber’s definition as an organization claiming a monopoly of legitimate violence. Remember that Godse was not trying to found some kind of extremist or fundamentalist state; he claimed to be quite satisfied with the Indian state as it evolved under Nehru and Patel after Gandhi’s death, and believed that it was his action that had made it possible. So he for one agreed with the above general law, and acted according to it.

Arguably, Gandhi also would have understood this general law. Certainly as it became increasingly clear what kind of state independent India was going to become, he spoke constantly of his waning influence, describing himself as a “back number” and a “spent bullet”, and, as mentioned above, in a variety of ways expressed a wish to die, and even a wish to be killed. He genuinely loved as his own sons the men who were building the new state, he said again and again that he didn’t want to interfere with their work, but being who he was, he could not stop himself. Thus his “fast to death” to force the government to honor its obligation to hand over to Pakistan its share of the national treasury – from the standpoint of state reasoning, utterly absurd behavior in time of war – can be seen as an almost pure manifestation of the above general law: “If you wish to engage in that kind of realpolitik, you must kill me.” In this case the government backed down and paid the money. It is said that this was the incident that persuaded Nathuram Godse to carry out the assassination.

But, it might be objected, where else in the world has such a thing happened? More than a hundred new states were founded in the 20th century. Where are the Gandhis who should have been sacrificed in each? How can you propose a general law on the basis of a single instance? The answer is simple enough. While surely every country has had and does have dedicated and good-hearted people struggling for a peaceful world, none of these has had the power – spiritual or political, as you wish – that Gandhi had. So if this general law has manifested itself only in the single instance of India, isn’t that because India was the only country that had a Gandhi to kill?

In what Robert Payne described as an “irony” of history, Gandhi’s funeral was arranged by the Indian military. (47) In his chapter entitled “The Burning”, Payne described the arrangements. The body was to be placed on top of a huge weapons carrier, and pulled by two hundred soldiers, sailors and airmen. “Four thousand soldiers, a thousand airmen, a thousand policemen, and a hundred sailors would march in front of or behind the weapons carrier, and in addition there would be a cavalry escort from the bodyguards of the Governor General.” Air force planes were sent to fly over and drop roses. (48) Payne wrote, “There were many who wondered whether the government had acted wisely in ordering the Defense Ministry to take command of the funeral.” (49) But to Nathuram Godse, the arrangements must have seemed perfect beyond his wildest dreams. While a million people watched, the military carried Mahatma Gandhi off to be burned. Payne says the procession resembled a “triumph”. Indeed.

It is said that after the cremation there was “a dramatic cessation of communal riots throughout the country.” (50) One wonders, were the rioting elements shamed, or sated?

Postscript

In his play St. Joan, George Bernard Shaw tells the story of another deeply religious, though by no means pacifist, fighter for her country’s national independence, who was burned as a witch after the battle was won. In the Epilogue to the play, Shaw has Joan return in the dream of King Charles, who she had crowned. One by one the other principal players – those who had ranted for her death, those who had reluctantly convicted her, those who had backed off and done nothing to help her – appear, and each confesses that he was mistaken and that Joan is to be revered. Then, using the extra poetic license the dream gives him, Shaw brings in a messenger from the year 1920, who announces that Joan has been canonized. All fall to their knees in worship of Saint Joan. Then Joan, with her typical wit, says,

Woe unto me when all men praise me! I bid you remember that I am a saint, and saints can work miracles. And now tell me: shall I rise from the dead, and come back to you a living woman? (51)

The embarrassed worshippers all rise to their feet and, mumbling excuses, one by one slink off the stage.

This article is a revised version of an article that appeared in Alternatives, 31 (2006).

C. Douglas Lummis, a former US Marine stationed on Okinawa, is the author of Radical Democracy and other books in Japanese and English. A Japan Focus associate, he formerly taught at Tsuda College.

Recommended citation: C. Douglas Lummis, “The Smallest Army Imaginable: Gandhi’s Constitutional Proposal for India and Japan’s Peace Constitution,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 3-2-10, January 18, 2010. 想像しうる最小の軍隊ーーガンジーのインド憲法私案と日本の平和憲法

Notes

(1) I wish to thank the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies for granting me the position of Rajni Kothari Chair in Democracy for 2004-5, during which this paper was written. In particular I wish to thank Centre Director Suresh Sharma for his many kindnesses. I am of course indebted to the entire faculty of the Center for encouragement and instruction in matters concerning Gandhi and Indian politics. Prof. Ashis Nandy of the Centre, Prof. R. Jeffery Lustig of California State University at Sacramento, and historian Frank Bardacke all read an earlier draft of this paper and offered valuable comments. Prof. Meeta Nath gave me very helpful assistance in identifying and locating resources. But if you don’t like what you read here, don’t blame them.

(2) The Hindustani Times, 5 Sept., 1931. Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Electronic Book version, New Delhi: Publications Division, v. 53, p. 312. In citations below, the Collected Works will be referred to as CW.