The Art and Life of Korean Poet Ko Un: Cross-cultural Communication

Brother Anthony of Taizé (An Sonjae)

Ko Un was born in 1933, which means that today he is nearer 80 than 70. He is surely Korea’s most prolific writer and he himself cannot say for sure how many books he has published in all. He guesses that it must be about 140, volumes of many different kinds of poetry, epic, narrative, and lyric, as well as novels, plays, essays, and translations from classical Chinese.

In the last two decades he has made journeys to many parts of the world, including Australia, Vietnam, the Netherlands, Mexico, Sweden, Venice, Istanbul . . . He makes a deep impression wherever he goes, especially when he is reading his poems in the husky, tense, dramatic manner he favors. It seems to make little or no difference that most of his audience cannot understand a word he is saying. He speaks little or no English but time after time a deep communication is established before anyone reads an English translation or summary of what he had been saying. After the drama of his own performance, the translations usually sound rather flat.

Ko Un’s ability to communicate beyond language is a gift that other Korean writers can only envy him for. There are some people who do not seem to need words in order to communicate, it is part of their charisma. There are many barriers to communication and many are the arts by which people have tried to overcome them. In the case of Ko Un, who cannot be every day giving readings, there is an urgent need to make translations of his work available. In bringing Ko Un’s writings to a world audience, I am acting to make cross-cultural communication possible in one particular case.

It may be good to begin with a summary of Ko Un’s life story, since that in turn may help to pinpoint some of the difficulties we encounter in translating his writings. He was born in 1933 and grew up in Gunsan, a town on the west coast of North Jeolla Province. Echoes of his childhood experiences in the Korea of the 1930s and 1940s can be found in the earlier volumes of the great 30-volume series known as Maninbo, the final volumes of which were published early in 2010. The traditional life of the farming villages, the intense awareness of extended family relationships, the poverty and the high level of infant mortality all make this a world far removed even from modern Korea, and very unfamiliar to non-Korean readers. Readers are expected to know that when Ko Un was a child, Korea was under Japanese rule, and to know what that signifies for Koreans still today.

In 1950, war broke out and Ko Un was caught up in almost unimaginably painful situations, which were in strong contradiction with the warm human community he had grown up in, as Koreans and outside forces slaughtered each other mercilessly. As a child, Ko Un had been something of a prodigy, learning classical Chinese at an early age with great facility, and encountering the world of poetry as a schoolboy through the chance discovery of a book of poems written by a famous leper-poet. His sensitivity was not that of an ordinary 18-year-old and he experienced a deep crisis when confronted with the reality of human wickedness and cruelty. His experiences included the murder of members of his family and the death of his first love as well as days spent carrying corpses to burial. He poured acid into his ears in an attempt to block out the “noise” of this dreadful world, an act that left him permanently deaf in one ear.

The traumas of war might have destroyed him completely but he took refuge in a temple and the monk caring for him decided that his only hope of finding a way out of his torment would be by becoming a Buddhist monk, leaving the world at a time when the world was a very ugly place. His great intellectual skills meant that he rapidly became known in Buddhist circles and after the Korean War ended he was given responsibilities. More important to Ko Un were his experience of life on the road as he accompanied his master, the famous monk Hyobong, on endless journeys around the ravaged country. Hyobong had been a judge during the Japanese period and had quit the world to become a monk after being forced to condemn someone to death.

Ko Un’s character is intense, uncompromising, he is easily driven to emotional extremes and he soon began to react against what he felt was the excessively formal religiosity of many monks. The reader of his work has sometimes to follow him through shadows cast by intense despair. He felt obliged to stop living as a monk and in the early 1960s he became a teacher in Jeju Island. Later in the decade he moved to Seoul. For several years he lived as a bohemian nihilist while Korea was brought toward its modern industrial development under the increasingly fierce dictatorship of Park Chung-hee. The climax came early in 1970 when Ko Un went up into the hills behind Seoul and drank poison. He nearly died but was found and brought down to hospital.

In November 1970 a young textile-worker, Jeon Tae-il, killed himself during a demonstration in support of workers’ rights. Ko Un read about his death in a newspaper he picked up by chance from the floor of a bar where he had spent the night. The impact of such a selfless death changed his life radically. He says that from that moment on he lost all inclination to kill himself. The declaration of the Yushin reforms in 1972, by which Park Chung-hee became president for life and abolished democratic institutions, sparked strong protests among writers and intellectuals as well as among the students who have always acted as Korea’s conscience. In the years of demonstrations and protests that followed, Ko Un’s voice rang out and he became the recognized spokesman of the ‘dissident’ artists and writers opposed to the Park regime. He was often arrested and is today hard of hearing from beatings he received then.

When Chun Doo-hwan rose to power in 1980, Ko Un was arrested along with Kim Dae-jung and many hundreds of Korea’s ‘dissidents’ and he was sentenced to 20 years in prison. It was there, as he faced the possibility of arbitrary execution, that he formed the project of writing poems in commemoration or celebration of every person he had ever encountered. No one, he reckoned, should ever be simply forgotten, since every life has immense value and is equally precious as historical record. This was the origin of the poems in the Maninbo (Ten Thousand Lives) series. Once the new regime felt sure of its hold on power, most of the prisoners were amnestied. Ko Un was freed in August 1982, in May 1983 he married Lee Sang-Wha, and in 1985 a daughter was born. He went to live in Anseong, two hours from Seoul, and began a new life as a householder, husband, and father, while continuing to play a leading role in the struggle for democracy and for a socially committed literature.

There are people who say that a poet’s life has nothing to do with the poems he or she writes but that is hardly tenable. It is a theory that considers poetry uniquely from a formal standpoint and excludes every aspect of personal, social, or historical context. Yet every word Ko Un writes is rooted in and informed by the experience of life I have just outlined. It is inconceivable that a man with such a life-story should not write poems deeply marked by it. He has a very intense sense of history, and of his writing as a mirror of Korean history.

On the other hand, his life story cannot tell us anything about the quality of Ko Un’s writing. He has always been such a controversial figure, from the moment his first book of poems was published and he renounced his life as a Buddhist monk, that in Korea evaluation of his work cannot be separated from responses to his life and social options. In particular, the Korean literary establishment has for a long time been divided about the general question of the social responsibilities of the writer. Many noted writers avoided trouble under dictatorship by refraining from commenting on social issues, writing poetry of intense self-centeredness, private ponderings full of abstruse symbolism, uniquely concerned with cultivating aesthetic dimensions.

Ko Un and many others chose not to follow them but instead defied censorship to write and speak out. For many years Ko Un could not get a passport. He was blacklisted as a dangerously subversive dissident. Because the military regimes claimed to represent true Korean democracy, any one who criticized them was by definition taking sides with the Communist enemy in the North! Older literary critics are often still unwilling to admit the value or interest of Ko Un’s writing. They have grown up with fixed ideas about what constitutes literary excellence and he does not fit in.

The topic of this paper can perhaps best be encapsulated in a question: What meaning can Ko Un’s work, and much modern Korean literature, have for people who have not experienced Korean history? Within any literary work we find not only the writer but also an implied audience. A Korean writer is not, usually, consciously writing for a uniquely Korean readership, but writers inevitably assume a certain shared level of experience in their readers. This is reflected, most obviously, in the many things that are taken for granted, that are not explained or mentioned explicitly.

The most familiar example of the difficulty that arises is the question of the division of Korea. A vast quantity of prose and poetry has been written in Korea on the theme of ‘division’ and such writings are a recognized category of modern Korean literature. The pain of the violent separation of families, the exclusion from the land of their birth of the millions who fled southward before and during the Korean war, the resulting sense of alienation from full national identity and the paralysis of vital aspects of Korean history, as well as the resulting lop-sided cultural changes related to industrialization and westernization in the south… all these topics and the related pain need no explanation in Korea, but they are a life-experience that is hardly conceivable to someone who has never left the peace of, say, rural Vermont or of Kyoto.

Ko Un’s poetry is not, usually, overtly political. He is not an explicitly protesting poet, as others have been. Almost the only poems that directly refer to political events are those few he wrote after the massacres in Kwangju in 1980. But that only makes the question more complex. Why, people might ask, does he write as he does? Why are there so few directly “social” poems and so many really rather difficult ones?

The answer would probably have to be the obvious one : because that’s the kind of poet (or writer) Ko Un is. Take it or leave it. And that is the kind of writing that I have been trying to translate into English for the past twenty years or so, having chosen to take it rather than leave it. I first worked on translations of Ko Un in tandem with the late Professor Kim Young-Moo of Seoul National University, who died in 2001, so in what follows I will often refer to ‘we’ since this began as a shared project.

First, we published in 1993 a selection taken from all the poems Ko Un had published before 1990, The Sound of my Waves. This was the first set of translations of his work published in the West. Then we published with Parallax Press (Berkeley) a volume of 108 Zen Poems to which the publishers gave the title Beyond Self. This was republished as What? in 2008.

In the meantime we translated Ko Un’s Buddhist novel, Hwaom-gyeong. It was finally published as Little Pilgrim in 2005. In the following years we prepared translations of 180 poems taken from the first 10 volumes of the Maninbo (Ten Thousand Lives) series. They too were published in 2005. In 2006, we were able to publish another volume of very short poems, Flowers of a Moment, where the poems are less challenging than those of What? The translation of a selection of poems from all the volumes Ko Un published prior to 2002 led to the publication of Songs for Tomorrow in 2008.

I have already said that Ko Un is now a well-known literary figure in every continent, thanks to his visits and the direct impact of his presence. Yet he cannot express himself directly in English and must always depend on an interpreter, except for the communication that passes directly, without words, by intuition and mutual sympathy. In any case, his poetry is written in Korean and must be translated. How to translate it is our great challenge. Once it has been translated, it has to be read and appreciated. That is where cross-cultural communication occurs.

I have implied that a major obstacle to reading Korean poetry lies in the very particular historical context in which it originates and to which it relates in often indirect ways. Yet on reflection, I do not believe that that is such a very great problem. Even non-Koreans seem able to understand the poem in which Ko Un tells of his childhood ambition to be emperor of Japan.

Headmaster Abe

Headmaster Abe Tsutomu, from Japan:

a fearsome man, with his round glasses,

fiery-hot like hottest red peppers.

When he came walking clip-clop down the hallway

with the clacking sound of his slippers

cut out of a pair of old boots,

he cast a deathly hush over every class.

In my second year during ethics class

he asked us what we hoped to become in the future.

Kids replied:

I want to be a general in the Imperial Army!

I want to become an admiral!

I want to become another Yamamoto Isoroko!

I want to become a nursing orderly!

I want to become a mechanic in a plane factory

and make planes

to defeat the American and British devils!

Then Headmaster Abe asked me to reply.

I leaped to my feet:

I want to become the Emperor!

Those words were no sooner spoken

than a thunderbolt fell from the blue above:

You have formally blasphemed the venerable name

of his Imperial Majesty. You are expelled this instant!

On hearing that, I collapsed into my seat.

But the form-master pleaded,

my father put on clean clothes and came and pleaded,

and by the skin of my teeth, instead of expulsion,

I was punished by being sent to spend a few months

sorting through a stack of rotten barley

that stood in the school grounds,

separating out the still useable grains.

I was imprisoned every day in a stench of decay

and there, under scorching sun and in beating rain,

I realized I was all alone in the world.

Soon after those three months of punishment were over,

during ethics class Headmaster Abe said:

We’re winning, we’re winning, we’re winning!

Once the great Japanese army has won the war, in the future

you peninsula people will go to Manchuria, go to China,

and take important positions in government offices!

That’s what he said.

Then a B-29 appeared,

and as the silver 4-engined plane passed overhead

our Headmaster cried out in a big voice:

They’re devils! That’s the enemy! he cried fearlessly.

But his shoulders drooped.

His shout died away into a solitary mutter.

August 15 came. Liberation.

He left for Japan in tears.

Such a story is not so hard to understand and the poems of Ten Thousand Lives are probably the easiest for non-Korean readers to understand. The main level of cultural difficulty in them are the references to aspects of traditional Korean life unfamiliar in other cultures, the sliding fretwork doors, the hot floors, the kimch’i and makkolli, the red pepper paste and the names of people. A matter for footnotes and intuition, not more. Robert Hass, the former American Poet Laureate, wrote of the Ten Thousand Lives poems in the Washington Post: “they are remarkably rich. Anecdotal, demotic, full of the details of people’s lives, they’re not like anything else I’ve come across in Korean poetry.” (Washington Post, “The Poet’s Voice” Sunday, January 4, 1998) They are not like anything else in Ko Un’s poetry, either. The selected poems translated in Songs for Tomorrow are arranged in chronological order, and some of the early poems are of a much more challenging kind:

Spring rain

O waves, the spring rain falls

and dies on your sleeping silence.

The darkness in your waters soars above you

waves–

and by the spring rain on your sleeping waters

by spring rain even far away

far-off rocks are changed to spring.

Above these waters where we two lie sleeping

looms a rocky mass, all silence.

But still the spring rain falls and dies.

With poems like this, the most important quality demanded of the reader is a familiarity with modern poetry, a readiness to allow images to work without a given framework by which to interpret them. Ko Un’s early work is closer to the general run of modern Korean poetry in that respect, with a strong note of melancholy and a fondness for puzzling riddles. The poetic effect is often dependent on the use of unexpected words and images, or seemingly irrational relations.

Read in chronological sequence, the evolution of certain themes and characteristics of Ko Un’s work soon becomes clear, and as Ruth Welte once wrote: “The political poems seem richer in meaning if the reader has a knowledge of Korea’s difficult modern history, but each poem also stands alone as statement on the movements of political systems and the damages that they can cause. Ko Un’s poems grow gradually more political but retain their deep stillness. Even the most politically specific poems have a timeless feel.” (The Chicago Maroon, November 9, 1999). One of the most famous of Ko Un’s “political poems” is “Arrows“:

Body and soul, let’s all go

transformed into arrows!

Piercing the air

body and soul, let’s go

with no turning back

transfixed

burdened with the pain of striking home

never to return.

One last breath! Now, let’s be off

throwing away like rags

everything we’ve had for decades

everything we’ve enjoyed for decades

everything we’ve piled up for decades,

happiness

all, the whole thing.

Body and soul, let’s all go

transformed into arrows!

The air is shouting! Piercing the air

body and soul, let’s go!

In dark daylight, the target rushes towards us.

Finally, as the target topples in a shower of blood

let’s all, just once, as arrows

bleed.

Never to return! Never to return!

Hail, arrows, our nation’s arrows!

Hail, our nation’s warriors! Spirits!

Recent Korean history has been blood-stained and the memory of those who have died for freedom, democracy, and reunification is regularly celebrated. Yet theirs’ is in some ways an ambiguous martyrdom, it would have been so much better if they had not died, so young. Ko Un’s poem expresses the feelings of many who took part in the demonstrations of the 1970s and 1980s at which it was often read. It may not communicate so well with people living in non-heroic situations of established democracy, although they ought to realize that there are many struggles demanding of them a similar level of commitment, sacrifice, and hope. Often they do not realize it and need Ko Un’s voice to wake them up.

While he was a monk, Ko Un underwent training in what Koreans call “Seon” and the English language calls Zen, following the Japanese. In fact he plunged into the most demanding and potentially dangerous form of Zen with such abandon that it caused him a severe psychic trauma. In any case, Ko Un is deeply influenced by the challenge to normal rational discourse and logic that is found in the Zen use of language. A certain kind of Zen aestheticism is familiar to many today in America and Europe, again mostly identified with things Japanese. Korean monastic Zen is altogether a tougher thing, I would say, and Ko Un’s Zen poems are surely far more challenging than anything else he wrote, both to translate and to read. The Zen poems in What? require the reader to let go of virtually everything:

A Single Word

Too late.

The world had already heard

my word

before I spoke it.

The worm had heard.

The worm dribbled a cry.

Summer

The sightless sunflower follows the sun.

The sightless moonflower blossoms in moonlight.

Foolishness.

That’s all they know.

Dragonflies fly by day

beetles by night.

A Shooting Star

Wow! You recognized me.

An Autumn Night

Daddy

Daddy

A cricket sings.

Ko Un seems to be a “poets’ poet.” Reading the Zen poems, Gary Snyder responded with a poem of his own:

Not just holding his Zen insights

And their miraculous workings tight to himself,

Not holding back to mystify,

Playful and demotic,

Zen silly, real-life deep,

And a real-world poet!

Ko Un outfoxes the Old Master and the Young poets both!

Tributes like that are the greatest reward a translator can receive. It means that communication has happened, and that the readers felt confident they were reading what the poet had written and wanted them to read. A lot is written today about the act of translation and the position of the translator, but certainly, as far as poetry translation goes, the translators should leave as little sign of their work as possible. The poet must speak, not they.

Part of the effectiveness of Ko Un’s Zen poems in English translation must be attributed to a third member to our team of translators. Effective translations of Korean poetry into English are rare because there are few translators who are writers (or even readers) of contemporary English poetry. It constitutes a serious limitation. We have been fortunate in finding an American poet and writer, Gary Gach, who is willing to go through our versions of Ko Un’s poems, point out places where the translations fail to communicate, and make suggestions for improvement.

This negotiation between “literal” translation and “poetic” translation is an extremely delicate one. George Steiner quotes Dryden’s definition of “to paraphrase”: “to produce the text which the foreign poet would have written had he been composing in one’s own tongue”. (After Babel p.351) All theories of translation and communication derive from that.

Ko Un has established his characteristic way of writing poetry, and the works from collections published in the 1990s that we are at present translating often show him transforming simple moments of everyday experience into poetry by a stroke of imagination, the irruption of an unexpected connection. This can be seen as a deliberate strategy of ‘defamiliarization’ which means that his readers can never know what will come next. His more recent poems are longer than the Zen poems but far richer than the quite simple evocative narratives of the Ten Thousand Lives. An example, chosen at random, might be “One Apple“:

For one month, two months, even three or four,

a man painted one apple.

And he kept on painting

while the apple

rotted,

dried up,

until you could no longer tell if it was an apple or what.

In the end, those paintings were no longer

of an apple at all.

Not paintings of apples,

in the end, those paintings were of shriveled things,

good-for-nothing things,

that’s all they were.

But the painter

gained strength, letting him know the world in which he lived.

He gained strength, letting him realize there were details

he could never paint.

He tossed his brush aside.

Darkness arrived,

ruthlessly trampling his paintings.

He took up his brush again,

to paint the darkness.

The apple was no more,

but starting from there

emerged paintings of all that is not apple.

If that seems too long or challenging, readers have the option of the short poems in Flowers of a Moment:

The sun is setting

A wish:

to become a wolf beneath a fat full moon

*

I have spent the whole day talking about other people again

and the trees are watching me

as I go home

*

Exhausted

the mother has fallen asleep

so her baby is listening all alone

to the sound of the night train

*

One rainy spring day

I looked out once or twice

wondering if someone would be coming by

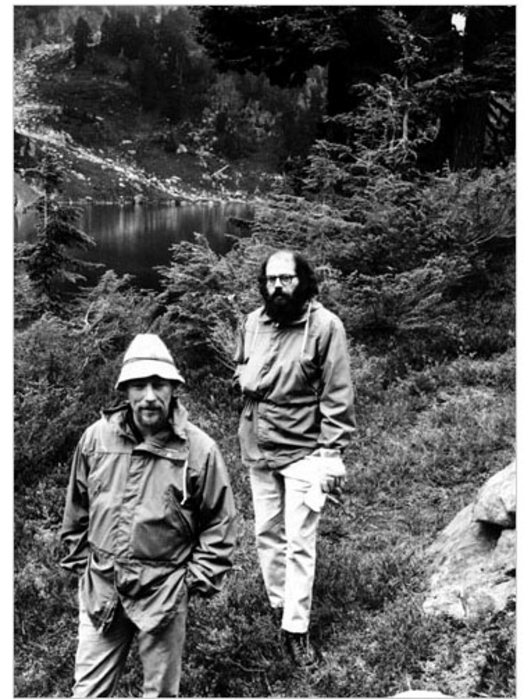

Today, more than 30 volumes of translations of Ko Un’s work into at least fifteen languages have been published, with more to come. It might be useful to end by giving a brief account of some critical responses to Ko Un’s work. When What? was being published, Allen Ginsberg wrote a moving preface which is one of the earliest in-depth responses to Ko Un written by a non-Korean, western poet:

Familiar with some of his earlier poems in translation, especially some of the later trickster-like naturalistic life sketches of Ten Thousand Lives — tender portraits, humane, paradoxical, “ordinary” stories with hilarious twists & endings, a little parallel to the “Characters” of W. C. Williams and Charles Reznicoff, I was stopped short by the present volume. What?’s the right title. 108 thought-stopping Koan-like mental firecrakers. (. . .) Ko Un backtracks from earlier “Crazy Wisdom” narratives and here presents what I take to be pure Zen mini-poems. I can’t account for them, only half understand their implications and am attracted by the nubbin of poetry they represent. Hard nuts to crack — yet many seem immediately nutty & empty at the same time. (. . .) Ko Un is a magnificent poet, combination of Buddhist cognoscenti, passionate political libertarian, and naturalist historian. This little book of Seon poems gives a glimpse of the severe humorous discipline beneath the prolific variety of his forms & subjects. These excellent translations are models useful to inspire American Contemplative poets.

|

Gary Snyder (left) and Allen Ginsberg in the Cascade Mountains, 1965 |

From 1995 Ko Un began to travel abroad regularly and in 1997 we find him giving readings with Gary Snyder and with the American Poet Laureate Robert Hass in Berkeley. The following year, in 1998, Robert Hass devoted a short article in the Washington Post newspaper to Ko Un. After a summary of Ko Un’s life in the context of modern Korean history he turns at once to Maninbo, the work that had struck him most deeply:

Only a handful of the poems have appeared in English translation, but they are remarkably rich. Anecdotal, demotic, full of the details of people’s lives, they’re not like anything else I’ve come across in Korean poetry. It’s to be hoped that a fuller translation of them will appear.

When we published our translations from the first 10 volumes of Maninbo in 2005, Robert Hass wrote the foreword, and then published an article in the New York Review of Books, a splendid tribute. He recalls first seeing and hearing Ko Un during a visit to Seoul in 1988 and, of course, that is one of the most important elements in Ko Un’s worldwide reputation–the impact of hearing him perform his poetry at readings: no other Korean poet has such powerful charisma. As Michael McClure once wrote:

In the world of poetry his reading is unique. There is no one who reads like this. Ko Un delivers his language with the intensity of one who was forbidden to learn his native Korean language as a child, but learned it anyway…… Ko Un’s poetry has the old-fashionedness of a muddy rut on a country road after rain, and yet it is also as state-of-the-art as a DNA micro-chip. Beneath his art I feel the mysterious traditional animal and bird spirits, as well as age-old ceremonies of a nation close to its history.

Hass describes the development of modern Korean poetry through the 20th century before quoting 2 very early poems by Ko Un from The Sound of My Waves. Of the first, “Sleep” he writes:

This is an inward poem, quietly beautiful. As English readers, we’re deprived of any sense of what it reads like or sounds like in Korean. It seems like mid-century American free verse, put to the use of plainness or clarity. The sensation of the sleeper, having opened his eyes and closed them with a feeling that he was still holding the moonlight, is exquisite. The turn in the poem—the shadow cast by the hunger for an entire purity—seems Rilkean.

Of the second, “Destruction of Life” he writes:

This has, to my ear, the toughmindedness of Korean Buddhism and the kind of raggedness and anger I associate with American poetry in the 1950s and 1960s, the young Allen Ginsberg or Leroi Jones. I’ve read that Korean poetry is not so aesthetically minded as Japanese poetry partly because it has stayed closer to oral traditions rather than traditions of learning, which may be what gives this poem its quality. It’s more demotic than “Sleep,” more spontaneous and tougher, less satisfied to rest in beauty.

Then he turns to Maninbo:

Maninbo seems to flow from a fusion of these traditions. For anyone who has spent even a little time in Korea, the world that springs to life in these poems is instantly recognizable, and for anyone who has tried to imagine the war years and the desperate poverty that came after, these poems will seem to attend to a whole people’s experience and to speak from it. Not surprisingly, hunger is at the center of the early volumes. Their point of view is the point of view of the village, their way of speaking about the shapes of lives the stuff of village gossip. They are even, at moments, the street seen with a child’s eyes so that characters come on stage bearing a ten-year-old’s sense of a neighborhood’s Homeric epithets: the boy with two cowlicks, the fat, mean lady in the corner house. The poems have that intimacy. Most of them are as lean as the village dogs they describe; in hard times people’s characters seem to stand out like their bones and the stories in the poems have therefore a bony and synoptic clarity. It’s hard to think of analogs for this work. The sensibility, alert, instinctively democratic, comic, unsentimental, is a little like William Carlos Williams; it is a little like Edgar Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology or the more political and encyclopedic ambitions of Charles Reznikoff’s Testimony. The point of view and the overheard quality remind me of the Norwegian poet Paal-Helge Haugen’s Stone Fences, a delicious book that calls up the whole social world of the cold war and the 1950s from the point of view of a child in a farming village. For the dark places the poems are willing to go, they can seem in individual poems a little like the narratives of Robert Frost, but neither Masters’s work nor Frost’s has Ko Un’s combination of pungent village gossip and epic reach. The characters, village wives, storekeepers, snake catchers, beggars, farm workers, call up a whole world.

Most striking is the way in which Hass links Ko Un’s work to poetry by a variety of poets from various countries, seeking to situate him by similarities and differences in a universal poetic context. Yet his comments also show a strong awareness of the importance of context in understanding Ko Un’s work, for he keeps referring to the concrete events of Korean history and to its culture. Ko Un has written that no poem can be “universal” because every poem arises within a particular poet in a particular place at a particular moment and in a particular language. Hass understands this, and he concludes;

perhaps it is enough to notice the fertility of Ko Un’s poetic resources. One would think that the poems would begin to seem formulaic, that the ways of calling up a life would begin to be repetitive, and they never are. In that way it is a book of wonders in its mix of the lives of ordinary people, people from stories and legends, and historical figures. They all take their place inside this extraordinarily rich reach of a single consciousness. Ko Un is a remarkable poet and one of the heroes of human freedom in this half-century.

American readers have often been drawn to poetry in translation because of the dramatic political circumstances that produced it rather than by the qualities of the work itself. But no one who begins to read Ko Un’s work will doubt that what matters here is the work itself.

I have quoted Hass at length because he has written with deep understanding of so many aspects of Ko Un’s work. One constant disappointment is the lack of extended book-reviews of our translations. I do not know how it is in other language-areas, but the English-speaking literary press is notoriously reluctant to review translations. We all know that very few translations are published in English, compared with other languages, perhaps because so much is written in English. “Foreign” writers are, with rare exceptions, little known to the American or British publics and as a result publishers and booksellers proclaim, ‘Translations do not sell.’

One other informative response to Maninbo comes in a long article on modern Korean literature by John Feffer published in The Nation (August 31, 2006):

This commemoration of Korean history and countryside, freed from strictures of form and diction imposed from the outside, follows in the tradition of minjung, or “people’s” culture. Ko Un has “gone to the people” for his inspiration, much like the narodniks, the Russian radicals of the nineteenth century, and the South Korean student movement activists of the 1980s who emulated them. But Ko Un has not summoned up some ethereal concept of the People. Maninbo, his masterpiece, is the People made flesh. Thanks to Ko Un, they continue to walk among us.

One very important question arises regarding what I would almost call the “Theory of Maninbo”. How can it best be read? In an article about Ko Un and Maninbo published in the most recent issue of World Literature Today, I wrote:

Each individual poem in Maninbo reaches out to all the other poems, just as each individual person only finds a meaningful life in meetings with other people, and Maninbo only finds its full meaning when read in that way. A process of anthologizing, selecting just a few of the “best” poems (as we have been forced to do) destroys that totality. The original title of Ko Un’s Buddhist novel that we translated as Little Pilgrim is Hwaŏmgyŏng (Avatamsaka Sutra) and the method of seeing all the poems (in Maninbo) as being contained in each one is an application of that Buddhist sutra’s fundamental teaching of the interconnectedness of all things, embodied in what is known as Indra’s Net. Indra’s net symbolizes a universe where infinitely repeated mutual relations exist between all members of the universe. This idea is communicated in the image of the net of the Vedic god Indra. Indra’s net is suspended with a multifaceted jewel at each of its infinite number of intersections, and in each jewel all the other jewels are perfectly reflected. One is all and all is one.

One way of interpreting that is to conclude that every poem in every volume should be translated so that non-Korean readers may have access to the full Maninbo experience. Another, equally valid, is to say that it is enough to have read just one of the 3,960 poems with real understanding; and that is not to deny the uniqueness of each one of them.

Brother Anthony of Taezé is Emeritus Professor, Department of English Language and Literature, Sogang University. A prolific translator of Korean poetry, his books include Ko Un’s The Sound of My Waves, What? 108 Zen Poems, Ten Thousand Lives, Flowers of a Monument, and Songs for Tomorrow. He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Brother Anthony of Taizé, “The Art and Life of Korean Poet Ko Un: Cross-cultural Communication,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 40-2-10, October 4, 2010.

References

English translations of Ko Un’s work

1. The Sound of My Waves (Selected poems 1960 ~ 1990) (Ithaca: Cornell University East Asia Series, 1992), tr. Brother Anthony of Taizé & Kim Young-Moo.

2. Beyond Self, (Berkeley: Parallax, USA, 1997), tr. Brother Anthony of Taizé & Kim Young-Moo.

3. Travelers’ Maps (Boston: Tamal Vista Publication, 2004), tr. David McCann. (A few selected poems)

4. Little Pilgrim, (Berkeley: Parallax, 2005), tr. Brother Anthony of Taizé and Kim Young-Moo. (The novel Hwaeomgyeong)

5. Ten Thousand Lives (LA: Green Integer Press, 2005), tr. Brother Anthony of Taizé, Kim Young-Moo & Gary Gach. (Selected poems from Maninbo volumes 1-10)

6. The Three Way Tavern (LA: UC Press, 2006), tr. Clare You & Richard Silberg (Selected poems)

7. Flowers of a Moment (New York: BOA, 2006), tr. Brother Anthony of Taizé, Kim Young-Moo & Gary Gach (Translation of the poems in the collection Sunganui kkot)

8. Abiding Places: Korea South and North (Vermont: Tupelo, 2006), tr. Sunny Jung & Hillel Schwartz (Selected poems from the collection Namgwa buk)

9. What? (Berkeley: Parallax, 2008) tr. Brother Anthony at Taizé & Kim Young-Moo. (A new edition of Beyond Self)

10 Songs for Tomorrow: Poems 1960-2002, (LA: Green Integer, 2008), tr. Brother Anthony of Taizé, Kim Young-Moo & Gary Gach (Selected poems)

11. Himalaya Poems, (LA: Green Integer, 2010) tr. Brother Anthony of Taizé & Lee Sang-Wha (Selected poems from the collection Himalaya)