Vietnam and China in an Era of Economic Uncertainty

Brantly Womack

Vietnam and China have much in common. There is no country more similar to China than Vietnam, and there is no country more similar to Vietnam than China. They share a Sinitic cultural background, communist parties that came to power in rural revolutions, and current commitments (China since 1978, Vietnam since 1986) to market-based economic reforms. Although the most recent war of both states was with one another, combat ended in 1991 and interaction has flourished since 1999. At present, together with the rest of the world, they both face a sharp increase in global economic uncertainty. What effects will global uncertainty have on the prospects for each country and on their relationship?

Map of East Asia and the Western Pacific.

[The Sea between Japan and Korea is called here the Japan Sea. Koreans refer to it as the East Sea.]

Clearly, in 2008 a massive change in the world economy began, requiring that a range of policies and attitudes be rethought. Both Vietnam and China will have to adjust their development strategies. Part of the adjustment is likely to include rethinking regional institutions as well as bilateral relationships.

The relationship between China and Vietnam has been normal for a decade, and is likely to remain so. However, it is also an asymmetric relationship. Each side has a different exposure to the relationship, and a global event such as the current crisis affects each differently. Vietnam’s economic situation is considerably less stable than China’s. The opportunities presented by China’s continued development are attractive to Vietnam, but at the same time both the government and the population are concerned about increasing dependence on China.

This article will first discuss the pre-crisis situation of the Sino-Vietnamese relationship and then the likely scope of the current global economic crisis. Every crisis is unique. The second major part of the paper will discuss the challenges posed to Vietnam and China by the new era. Vietnam and China will face some similar challenges, such as the development of domestic markets and the reorientation of foreign trade. However, they will also face challenges specific to their individual situations. For Vietnam the problem of economic adjustment is more urgent, while for China the problem of sustainable development is more urgent.

The final part concerns the Vietnam-China relationship in the new era. The existing principles and institutions of the relationship provide a strong foundation for continued cooperation. However, global turbulence provides a new and uncertain context for the relationship, and because of Vietnam’s greater exposure to China its anxieties about dependence on China are heightened. Given the asymmetry of the relationship, it is important that it is buffered by other relationships as well as regional and global organizations.

The Global Economic Crisis

The Pre-Crisis Situation

China and Vietnam formally normalized their relationship in late 1991, after the resolution in principle of the Cambodia dispute and the return of Prince Sihanouk to Phnom Penh. Building momentum and overcoming suspicions took time, but by 1999 both governments committed themselves to “long-term, stable, future-oriented, good neighborly, and all-round cooperative relations.” (长期稳定, 面向未来, 睦邻友好, 全面合作; Láng giềng hữu nghị, hợp tác toàn diện, ổn định lâu dài, hướng tới tương lai). This “16 Word Guideline” became the mantra to be repeated at every official meeting, but it was not empty talk. It was assumed that the relationship would be one of increasing mutual benefit, and that problems and differences could be managed in that context.

The first major milestones of normalcy were agreements on demarcating the land border and a series of discussions on utilization of the Gulf of Tongking. No progress was made on resolving claims to the Paracel and Spratly island groups, but the 2002 agreement between China and ASEAN concerning peaceful conduct in the South China Sea helped to limit the conflict potential of this arena. Meanwhile, diplomatic and economic contact increased enormously.

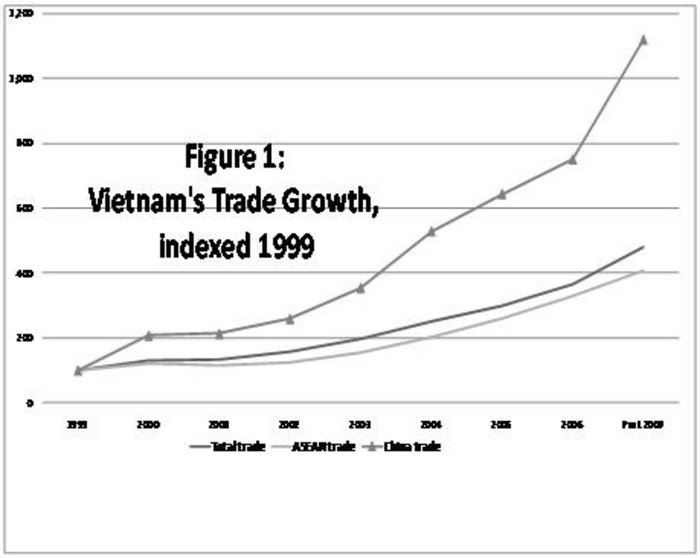

As Figure 1 illustrates, trade with China has outpaced the generally rapid growth of Vietnam’s total trade, increasing its share from 6.1 percent in 1999 to 14.3 percent in 2007, and from one-fourth of Vietnam’s trade with the rest of ASEAN to two-thirds. Keeping pace with thickening economic relations, exchanges of official visits at all levels, educational exchanges, and tourism have also grown rapidly.

However, the relationship between China and Vietnam is asymmetric in every respect, and asymmetry creates fundamentally different perspectives on the relationship. Vietnam’s GDP in 2007 was three percent of China’s.1 China is the world’s second largest merchandise exporter and third largest importer; Vietnam ranks fiftieth and forty-first, respectively. China and Vietnam have comparable levels of trade per capita, but for Vietnam trade is twice as important. Vietnam’s trade to GDP ratio is 156, while China’s is 71.3. Trade structure is quite different. For Vietnam, agricultural, fuel and mining products are 46.3 percent of total exports; for China they constitute only 6.7 percent. Vietnam is a net exporter of oil and coal; China is also a net exporter of coal. Chinese goods fill Vietnamese markets. China is the chief source of Vietnam’s machinery, computers, chemicals, and textiles. More surprisingly, China sells three times more fruit and vegetables to Vietnam than it buys. These differences in economic capacity and structure, as well as in global weight, create a general asymmetric framework for the economic relationship.

As Figure 2 illustrates, the disparity between the economies of China and Vietnam is accentuated by an imbalance between imports and exports. China is easily Vietnam’s number one source of imports, equal to 79 percent of imports from all of ASEAN, and the latter includes a large amount of refined oil products from Singapore. While Vietnam exports textiles as well as commodities such as gems and coffee to developed countries, most of China’s purchases are raw materials. For example, Vietnam exports 70 percent of its rubber to China, but it buys two-thirds more rubber products from China than it sells. Generally speaking, Vietnam relies on China for a very broad range of its imports, twenty percent of its total imports, and sells coal, oil and food products to China. Vietnam is a perfect external market for Chinese goods because of similar economic conditions and consumer cultures and low transportation costs. While Vietnam cannot find a comparably priced source for much of what it buys from China, China can get its fuel and tropical products elsewhere.2 Moreover, Vietnam’s coal reserves are dwindling. In 2010 domestic demand for coal will approximate total production, and by 2015 Vietnam expects to import 25 million tons, more than half the amount of current domestic production. But in the first six months of 2009 more than half of production was exported—two-thirds of the total to China—and it will be difficult to replace coal’s foreign exchange earnings.3 Meanwhile oil output has declined since 2005. Oil exports in 2007 were lower than they had been in 2000, though earnings were greater due to price hikes. Thus the trends in bilateral China trade are against Vietnam. It imports ever more, and in the absence of a significant change in the composition of its exports, it will have less to sell.

For China, trade with Vietnam is much less important than it is for Vietnam. In 2007 Vietnam ranked 22nd in China’s exports, between Thailand and Mexico, and 38th in imports, between Mexico and Venezuela.4 Among Asian partners Vietnam ranked 16th in exports, behind all of the “big five” ASEAN states, and 11th in imports, behind Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand.

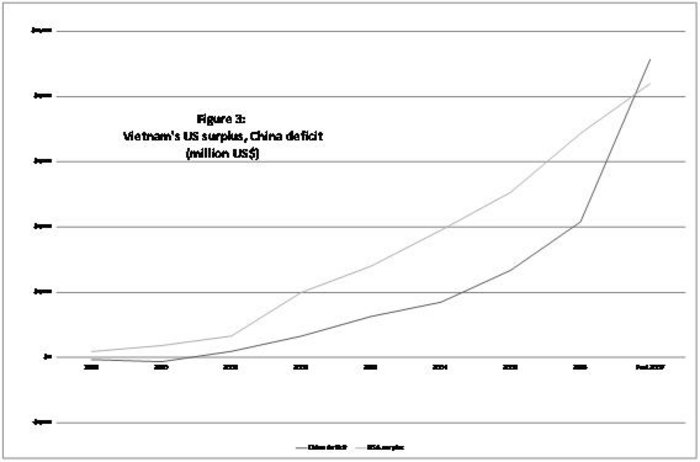

While Vietnam’s trade deficit with China has been large and growing, Figure 3 shows that it has been balanced by its trade surplus with the United States. However, the sharp rise in the China imbalance from 2005 has erased the advantage. Vietnam also runs a large surplus with the EU, but as a result of the current financial crisis, the developed country consumer market is down, while Vietnam’s demand for Chinese goods continues to grow. In 2007 the US surplus covered 92 percent of the China deficit. In the first half of 2009 it covered 81 percent. Meanwhile, although the Vietnamese economy is growing, in August 2009 its imports were down 28 percent, its exports were down 14 percent, and tourism was down 18 percent.5 The current crisis is thus not only a domestic problem for Vietnam, it also directly affects economic and trade dimensions of its relationship with China. As we shall see, it affects the political relationship as well.

Global Uncertainty

The global economic crisis that has riveted world attention since mid-2008 is the most serious systemic economic crisis since the Great Depression. As a systemic crisis, its chief existential effect is a vast increase in uncertainty. The two major crises of the post-Cold War era, the collapse of the Russian economy in the 1990s and the Asian financial crisis of 1997, occurred within a global system that was widely presumed to be stable and which indeed absorbed the shock. The effects of the 2008 crisis touched off by the United States rocked the world economy and its effects continue to reverberate.

Consider fluctuations in the price of oil. In December 2003, it was US$30 per barrel. In July 2008 it reached US$145 per barrel, before plummeting by December 2008 to less than US$40. And oil is only one indicator of the current fluctuation of asset values.

Prediction becomes virtually impossible in a systemic crisis. Even a correct structural analysis cannot specify when a predicted event will occur. It is relatively easy to judge a bridge unsound, but impossible to know when it will collapse. Moreover, structural change is rarely driven by one structural element, but rather by the interaction of interdependent factors.

The previous global systemic crisis, the Great Depression of the 1930s, is a poor model for prediction. There were far fewer sovereign actors in the colonial era. Vietnam was hurt more than France because France subordinated Vietnamese interests to its own. Now the 192 members of the UN will be making their own decisions. It is still the case that not all states are equal, but the clout of state actors has become more complex as well. A debtor United States must work with a creditor China. There were also no functioning regional or global economic organizations in the 1930s. Now there are both regional and global venues for cooperation on common policies. A more mixed blessing of the present era is the role of the dollar as the global currency. On the one hand, it provides an international standard of exchange that was missing in the 1930s. On the other hand, it might prove an unreliable standard, and it is notable that the US was the source of the current crisis. Lastly, the transportation and communications revolutions have created a near-instantaneous capacity for international interaction. The problems, processes, and solutions of the present crisis will necessarily be novel.

Thus the key characteristic of the current crisis is not that all suffer (though they do), but that all are uncertain about when and how the suffering will end. The dimensions of the current uncertainty will exert a profound effect on the planning and priorities of individuals and nations. In relatively stable times, it is rational to act according to one’s marginal advantage, to choose the better instead of the merely good. In times of uncertainty, it is rational to be cautious. If future prospects are uncertain, it becomes more important to secure a solid benefit than to take a better but riskier option. In general, the developed world has been relatively stable and prosperous during the post-Cold War era, and it has become habituated to acting according to marginal advantage. The stability and progress of the developed world has also had a broader stabilizing effect on the global economy. Currently that situation and its logic are in a period of traumatic transition. We are now in a new era, one of uncertainty.

Uncertainty is not new to Asia. The Asian financial crisis of 1997 was a profound experience of regional economic uncertainty. Although Vietnam and China were not the hardest hit, growth slowed. The Asian financial crisis led to greater determination on the part of ASEAN to coordinate economic policies, and eventually to greater ASEAN-China and ASEAN +3 cooperation.

However, the Asian financial crisis differed in three major ways from the current crisis. First, the Asian financial crisis took place within a relatively stable global environment. Uncertainty was limited to the region, and it was largely limited to finance and its budgetary consequences. Second, recovery plans could be based on familiar patterns of increasing production and selling to markets in the USA and Europe. Now these markets are undercut by more cautious consumption and the danger of tariff wars among nations is high. For both China and Vietnam, membership in the WTO played an important role in encouraging trade and investment while limiting their tariff and trade options in responding to the crisis. Third, the developed countries, especially the USA, were rather indifferent to the difficulties of Asian governments. It is unclear whether countries will help each other in the current crisis, but globally they are all in the same stormy waters, though in different boats.

Global Certainties

The largest nodes in the multi-nodal international economy are the United States and Europe, and, as Giovanni Arrighi argues, they are likely to remain the largest nodes even in an era of uncertainty.6 Their share of the world market and of investment will decline, but they are large and wealthy economies, with tremendous advantages in capital and technology. Even as they try to protect their domestic producers, they will find that they have become dependent on imports that cannot be sourced internally. To be sure, lower consumer demand, higher transportation costs, and pressures to create jobs at home will reduce the current prominence in the world economy of the USA and Europe, but other than the upper-income segments of the world’s largest cities there are no markets like them, and no comparable concentrations of financial services. The United States has 22.5 percent of the world’s GDP, and the five largest states of Europe together have 16.7 percent.7

That said, another major trend in the world economy that is likely to continue and even strengthen is the growth of middle-income countries and the emergence of some low-income countries from destitution. In 2005 middle-income countries accounted for 32 percent of world GDP, and lower-income countries another 7 percent— together the same as the USA and the top five European economies combined. China (9.7 percent) and India (4.3 percent) are of course important individual components, but together they are less than half of the middle-income share. To the extent that middle-income GDP is dependent on producing for high-income markets it will be influenced by world crisis, but to the extent that it produces for itself it should be relatively better off. Assuming that there is more room for growth in middle-income consumer markets they are likely to do relatively better over the next five years.

Another global trend that will help some countries and slow others is growing pressures on world resources, including energy, materials, and food. These pressures will be offset somewhat by decreased demand from developed countries and in the case of oil by alternative energy sources, but the limitations of sources and increasing costs of inputs (labor and technology) will cause prices to rise. Since the export volume of many of these products is generated by middle-income countries, this trend should encourage the increase in middle-income share in both absolute and relative terms. However, the specific impact of higher resource prices will be different in each country. The effects are complicated for China and Vietnam. Vietnam is a resource exporter, but with limited production and reserves and an urgent need to pay for imports. China is a resource importer, but with dollars to pay for them.

Related to the increasing price of resources will be increasing problems of sustainable development. Sustainable development is broader than the availability of resources since it also includes the byproducts of production: pollution, water shortage, and social disruption. Population density is as important as level of development in determining the urgency of sustainable development issues, since the population immediately surrounding a production site are most exposed to its environmental effects. Beyond the immediate by-products of production, rapid development can exacerbate economic inequalities and insecurity, and can lead to social disruption. China’s concentration on maximum growth during the reform era has made it vulnerable to a broad range of sustainability crises, from food and water shortages to social unrest. Vietnam has also pursued maximum growth, but its later start and more modest achievements have not sharpened the contradictions of sustainability to the same degree.

Finally, the number and seriousness of truly transnational and global issues, such as pandemic disease, terrorism, and so forth, are likely to increase. These issues can only be effectively addressed through international cooperation. The region’s experience with SARS in 2004 was a sobering lesson, and the flickering cases of avian flu are a reminder that worse can happen.

Challenges for Vietnam and China in the New Era

Similarities

Both Vietnam and China have set a high priority on maximizing economic growth, and a major component of this strategy has been the encouragement of production for developed country markets. As Table 1 shows, both rely on markets in USA and Europe for roughly one-third of their exports, and trade to these markets has more than kept pace with their general increase in trade. Moreover, both Vietnam and China rely on heavily favorable balances in their developed country trade to counter deficits in other areas. Considering that the USA and the five largest European economies together are 39 percent of the world’s economy, it is understandable that they would be major parts of the export strategies of other countries. Nevertheless, it amounts to a large exposure to the epicenter of the current global uncertainties.

The pre-crisis trade pattern therefore accentuates the effects of global economic crisis for both Vietnam and China, and will require readjustment of priorities. Although the USA and Europe will remain major markets, they will certainly contract. Losses are unavoidable in sectors of the economy that have been created specially to serve these markets. Capital losses are felt primarily by foreign investors, but job losses are a domestic problem. Moreover, these problems are concentrated in export-oriented localities that have hitherto been leaders in economic development. The most immediate challenge therefore for both Vietnam and China will be to soften the losses for those most affected by the crisis.

The deeper and more important challenge is to shift external development strategy away from producing goods for existing markets toward developing new markets. It is important to maintain share in shrinking markets, but it is more important to establish share in growing markets. The fastest growing markets in the new era of uncertainty are likely to be in the middle-income countries, including China itself, and the greatest long-term opportunities will be in the poorest countries. Both Vietnam and China have special advantages in these markets because they are themselves developing countries and therefore are acquainted with the needs of such economies. However, foreign direct investment is not likely to play a leading role in production for developing country markets, so governments will have to be active in encouraging local entrepreneurship and development.

The most important challenge of market development will be within the domestic economies of Vietnam and China. One’s own market is the most reliable one in a time of global uncertainty. Spreading the national economic infrastructure and developing domestic consumption are always major priorities, but they take on new importance in uncertain times. Moreover, for both Vietnam and China, the Chinese domestic market is the major opportunity in Asia.

Global uncertainty has lowered rates of GDP growth in Vietnam and China, and this creates the temptation to try to maintain the current growth rates at all costs. Both China and Vietnam have adopted major stimulus packages—15 percent and 6.8 percent of their respective GDPs—in order to counter the initial effects of the slowdown.8 However, the concentration on maximum economic growth is a problematic strategy in good economic times, and it is more questionable in bad times. Sustainable development should be even more important in an era of global uncertainty. Unsustainable development creates crises in the present and future. A slower but more solid pattern of development prevents the magnification of uncertainties. As Premier Wen Jiabao has argued, scientific development must address the problems of social inequalities and promote social harmony as well as coping with obvious industrial problems such as pollution.

A final common challenge for Vietnam, China, and their neighbors is to develop and strengthen regional institutions, especially in areas of development, trade, and finance. The weakness and variability of the US dollar underlines the importance of East Asia providing its own international financial stability, and the problems of big international service providers such as AIG and the now defunct Lehman Brothers shows the advisability of locally-based and regionally-based institutions. However, the strength of ASEAN, the most successful regional institution in East Asia, has been based on openness to the rest of the world rather than the formation of a closed system, and this should remain a principle of future institutional development.

Differences

Despite the basic similarities of the situations of Vietnam and China in facing global economic uncertainty, the challenges they face are different in some important respects.

Vietnam is a smaller economy, and it is less wealthy than China. China has had the advantage of seven additional years of reform and openness, and it did not have the disadvantages of war and of lingering international hostility. The United States normalized relations with China in 1979, but with Vietnam only in 1995. Moreover, Vietnam entered the WTO in 2007, while China entered in 2001.

Since Vietnam is a smaller boat riding lower in the water, it has more urgent difficulties in adjusting to the current crisis. Before the crisis began inflation was a problem, peaking at 28 percent in August 2008. Deflationary measures adopted in April 2008 eventually brought inflation under control, but the collapse of developed country exports (total exports down 24 percent year-on-year in January 2009) led to opposite policies of fiscal stimulus and damage control. China went thru a similar cycle of inflationary pressures, deflationary policies, and stimulus, but inflation was much milder (5 percent) and it had a huge trade surplus.9 Since 2003 Vietnam has run trade deficits with all ASEAN countries except Cambodia and the Philippines, and except for those two and South Africa, the rest of its surpluses have been with developed countries.10 In June 2009 the IMF estimated Vietnam 2009 GDP growth at 3.5 percent and judged it to be “weathering the crisis relatively well.”11 This is in contrast to Thailand, for instance, which expects a contraction of 3 percent despite the beginnings of recovery.12 However, the IMF was concerned about the possible fiscally destabilizing effects of the stimulus package. Clearly Vietnam’s first problem is managing as best it can the problems caused by the current crisis.

As to market reorientation, Vietnam’s greatest single opportunity is China. Its border with Guangxi and Yunnan give special access to southwest China, and it has good maritime access to Guangdong and Hainan. But besides these neighboring areas, the vast improvement in China’s rail and road transportation in the south greatly facilitate Vietnam’s access. Joint development projects at the major gateways of Lang Son/Pingxiang and Mong Cai/Dongxing offer unique advantages, as do larger projects such as plans to develop the Gulf of Tonkin region. Exports to China have increased. Trade grew by eleven times from 1999 to 2007, but the export of petroleum, coal, and other resources is a significant part of the increase. In the first half of 2009 total trade with China was 16 percent, almost at the level of ASEAN trade (18.4 percent). Exports to China were 7.5 percent of total exports, about half of exports to US (19.5 percent), while China was the source of 23 percent of Vietnam’s imports, almost three times imports from the EU and a billion dollars more than from ASEAN.13

Vietnam’s challenge in diversifying exports to China is that it is difficult to find products and areas of consumption in which it can compete successfully with domestic Chinese producers. However, a more sophisticated and sensitive marketing effort of manufactured products to China should yield results. Many developed countries trade commodities with one another when neither has a clear competitive advantage. Vietnamese manufacturers could establish brand names and reputations in Chinese markets and search for market niches where their products would be better than locally available ones.

Besides trade with China, Vietnam’s markets in ASEAN and East Asia have room for expansion. Its export increase 1995-2005 with Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Japan were below the average export growth of 595 percent. While these markets are hit hard by the current crisis, there may be areas for improvement. Beyond Asia, China’s successes in Latin America, the Middle East and Africa suggest opportunities since Vietnam has similar factor advantages in production, if not in scale and capital. The increases in Vietnam’s trade with South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand are heartening.

Vietnam does not have enough capital for a general program of long term investments in poorer countries, but its close relations with Cambodia and Laos could be developed further. As China builds longitudinal links to mainland Southeast Asia, Vietnam can continue to cooperate with neighbors to strengthen latitudinal links. These projects are not in conflict, and should enhance the benefits of each.

In contrast to Vietnam, China’s currency problems are ones that most other countries would envy—too many dollars and an undervalued currency. While these also pose sharp and unusual problems for China’s leadership, these problems are not comparable to Vietnam’s in scale and urgency. Moreover, while its export industries aimed at developed markets will suffer, the rest of the economy will be more able than Vietnam’s to pick up the slack. China’s major strategic challenge will be re-thinking its commitment to maximum economic growth and decisively shifting its priorities to sustainable development. If China does not cope successfully with the challenges of controlling the environmental and social effects of maximum growth, then it will face a future crisis more serious for itself than the current global one.

In the current crisis China is likely to be the least negatively affected of the major world economies, and since it already has the highest growth rate, its share of the world economy is likely to rise in absolute terms and still more rapidly in relative terms. More important than China’s fiscal advantage are its large and dynamic domestic market and its forward-looking investments in transportation and communication infrastructure.14 Moreover, China’s investment in higher education and research has prepared it to move to the front lines of technological innovation. In general, Asia’s share in the world economy can be expected to rise, and China’s centrality to Asia will increase. However, if China does not address the problems of sustainable development in a timely fashion, it will find itself increasingly distracted by environmental and societal crises.

Before the crisis China was already very well positioned in the global economy. It lists approximately 250 trading partners. Its investments in Latin America and Africa have created new markets and new sources for raw materials. From 1997 to 2006 its trade with Latin America and Africa grew 978 percent and 838 percent respectively, far outpacing its general trade growth.15 Trade growth with other regions was also impressive, however, ranging from 500 to 600 percent, with the weakest region being Asia. Of course, trade with Asia was increasing from a higher base. By moving beyond its immediate neighborhoods and developing markets and sources throughout the world, China has reduced its exposure to particular economic fluctuations and has increased its opportunities.

Both Vietnam and China face the challenges of regional reorganization, but from different vantage points. For China, the problem is a multi-regional one. It must simultaneously manage its relationships with Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia, and Central Asia. Its position as the new center of the general Asian economy and as its most promising market puts it in the macro-regional leadership position, and capable of voicing important concerns and ideas regarding global structures. The electoral victory of the Democratic Party in Japan’s August 2009 election puts it in a better position to cooperate with China in regional initiatives. For Vietnam, the most important regional task is to strengthen ASEAN, both internally and in ASEAN’s collective relationships with China and India.

The Vietnam-China Relationship in the New Era

It is the good fortune of Vietnam and China that before the current era of global uncertainty they normalized their relationship using principles and practices that are quite compatible with the requirements of the new era. The “16 Word Guideline” enunciated in February 1999 is still quite applicable. More generally, the mutual commitment to the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence formulated in1954, multipolarity, openness, autonomy, and the peaceful settlement of differences, remain a vital framework for the relationship. More specifically, the settlement of the land border, the management of Tonkin Gulf differences, and the decision in principle to cooperate in developing the Spratly Islands are important not only because they reduce points of conflict, but also because the successful negotiation of these sensitive issues provides a pattern for the future.

Nevertheless, managing an asymmetric relationship poses special challenges for each side.16 For the larger side, the challenge is to reassure the smaller side that it respects its identity and autonomy. Because the larger side is capable of infringing on the interests of the smaller side, it must demonstrate that it respects the smaller side’s autonomy and is willing to negotiate rather than bully. For its part, the smaller side must convince the larger that it respects the differences in capacities and does not intend to challenge the larger. In a word, the smaller side must be deferential. But deference does not mean that the larger side controls the smaller and can dominate the relationship. Quite the opposite. The smaller side can be deferential only if the larger respects its interests and autonomy. The exchange of deference by the smaller side and recognition of autonomy by the larger side makes possible normal asymmetric negotiation. A normal bilateral relationship is beneficial to China as well as to Vietnam. While it might seem that the larger side could get more from the relationship by simply bullying the smaller side rather than compromising, in fact the smaller side is quite capable of resisting the larger. No country has a longer history of patriotic resistance than Vietnam. If a hostile stalemate develops between the two, then both sides lose the opportunities of mutually beneficial relations.

Despite the general commitment to normalcy, there have been tensions between China’s tendency toward complacent self-assertion and Vietnam’s anxieties concerning its vulnerability to China. Despite the official settlement of the land border by a 50-50 assignment of disputed territory, there has been an undercurrent of patriotic disapproval in Vietnam of yielding any Vietnamese land to China. Incidents in the Tonkin Gulf and South China Sea do not now lead to the public confrontations that occurred even in the 1990s, but they are watched closely as signs of possible encroachment. More seriously, moves by China in 2007 to enforce its claim to sole sovereignty of the Paracel and Spratly Islands led to rare public demonstrations in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.17 Similarly China’s development of a submarine base in Hainan stirred Hanoi to contract in April 2009 for six Russian submarines at an estimated cost of $1.8 billion.18 These tensions in the relationship are magnified in the international media and by anti-regime activists among the overseas Vietnamese, but they do express a common uneasiness about vulnerability to China and a suspicion about China’s motives.

Trade with China has been an acutely mixed blessing for Vietnam ever since it resumed in 1990.19 On the one hand, much desired consumer goods began to flood in, accompanied by important producer goods such as insecticides and tools. On the other hand, the competition from Chinese products was devastating for Vietnamese industry. This led to import bans on Chinese products in 1992, but smuggling was so prevalent that the bans were ineffective. Having the Chinese superstore next door is good for shopping but bad for the neighborhood store.

Global uncertainty has made more difficult the management of bilateral asymmetric relationships. The best example in 2009 was the hotly disputed decision to allow a Chinese company, Chalco, to develop a bauxite mine in Vietnam’s Central Highlands.20 The world’s third largest bauxite deposits are located there, and Vietnam is hoping to attract US$15 billion in investment by 2025. In 2007 Vietnam reached agreements with Alcoa and Chalco concerning 20-40 percent joint ventures on mining and processing projects, but there was public outcry. General Giap, now 97 years old, wrote a letter of protest to the Politburo, and many others questioned the move.

General Giap

Environmental problems included disruption in the Central Highlands, with large-scale surface mining and electric power and toxic byproducts from the processing of bauxite. But the China-invested project was particularly targeted, with claims that thousands of Chinese workers would be brought in to do jobs that unemployed Vietnamese could do, and that Chinese presence would be a security threat. In April the government announced that the current project under contract with Chalco would continue, but that it would postpone the decision concerning foreign investment in bauxite mining and processing. Other projects would require additional environmental and economic assessments.

Vietnam is hardly the only country facing dilemmas concerning Chinese investment in resources. The United States prevented the sale of Unocal to China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) in 2005, and Australia is wrestling with questions of how much Chinese investment to allow in its natural resources. But for Vietnam these concerns are amplified by the disparity between it and its larger neighbor.

The dilemma that the Vietnamese government faces in the bauxite project points to the basic dilemma of asymmetric relations made more acute by global uncertainty. On the one hand, Vietnam is in need of investment and trade. Chalco is the world’s third largest aluminum producer and China currently imports three-fourths of its alumina. The development of a major new resource is an opportunity that can’t be ignored, and China is a natural partner. On the other hand, the fact that China is growing so fast and the idea of China as threat is so ingrained in national consciousness creates a fear that rises in proportion to the opportunity. Just as the opportunity would benefit some more than others in Vietnam, the fear can be exploited by interested groups to claim the flag of true patriotism. Vietnam has proved itself capable of going it alone. In February 2009 it opened the $2.5 billion Dong Quat oil refinery, a project that had been abandoned because of projections of unprofitability by three different groups of major international partners since construction began in 1995. However, uncertainty raises the cost of stubbornness as well as its incentive. If the world economy were more stable Vietnam would neither be so desperate nor so anxious. Uncertainty increases the interest in opportunity but at the same time extends the horizons of doubt and fear.

Just as the tensions of bilateral asymmetric relationships are heightened by international uncertainty, they can be buffered by multilateral regional and global institutions. If Vietnam had not succeeded in joining the WTO before the current crisis it would be more anxious and fearful in its relationship with China. Ironically, its factor similarity to China attracted investment from companies wanting to diversify their political exposure. Multilateral agreements and institutions provide a web of common international expectations that reduce concerns about fluctuation in bilateral relations.

The most important multilateral organization buffering the Sino-Vietnamese relationship is ASEAN and, more broadly, to ASEAN +3. Only one-fourth of ASEAN trade is within ASEAN, and, as a consensus organization, it is more impressive for the regional atmosphere it creates than for the policies it adopts. But over time it has transformed both the regional political environment of Southeast Asia and the region’s external image.21 The admission of Vietnam into ASEAN in 1995 had two important bilateral effects. It prodded the United States into finally recognizing Vietnam, and it gave Vietnam the confidence to pursue closer relations with China. Rather than balancing against China, regional security (and normalization with the United States) enabled Vietnam to feel less isolated and therefore less at risk in an asymmetric bilateral relationship, especially one that was similar to that of its fellow ASEAN members.

ASEAN’s soft-line, consensual approach prompts predictions of its demise whenever Southeast Asia faces major crises. But unlike a defensive alliance such as NATO, its function is not to counter an identified external threat, but rather to facilitate a regional adjustment to new situations. The Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1979 led to the alignment of ASEAN in an anti-Vietnamese entente, with Thailand designated as the front-line member. ASEAN seemed fragmented in its policy as the Cambodian stalemate moved into endgame in the second half of the 1980s, but by the mid-1990s it took the bold move of becoming a truly regional organization by admitting Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. ASEAN’s efforts at economic coordination had been weak before the Asian financial crisis, but beginning with the Sixth ASEAN Summit in Hanoi in December 1998 members re-committed themselves to an ASEAN free trade area (AFTA), and, perhaps more importantly, took a more active role in developing regional relations with Japan, China, and Korea (ASEAN +3). The most spectacular result of these explorations was the ASEAN-China free trade area (ACFTA or CAFTA) announced in 2002 and targeted for full operation in 2010-15 and currently on schedule. The economic progress was complemented on the political and security side by the “Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea” signed in 2002 and China’s accession to the ASEAN Treaty of Amity (as the first non-ASEAN member) in 2003.22 Vietnam’s participation in the ASEAN initiatives helped reassure China of Vietnam’s deference and also provided Vietnam with a regional umbrella for its own bilateral policies.

How will ASEAN respond to the current crisis? With the momentum of ASEAN and more broadly Asian economic integration since 2002, the least likely response would be the demise of ASEAN. Even in the unlikely event of protectionism in the developed world, ASEAN and East Asia will probably be cooperative and inclusive in their response. Considering the common economic problems of dollar exchange rate uncertainty, disruptions in employment and foreign investment, weakening of developed country consumer markets and the need to develop domestic consumer bases, a variety of new initiatives might be anticipated. On the foreign exchange and investment front, the Chiang Mai currency swap facility was raised from $80 billion to $120 billion in February 2009, and further efforts to buffer local currencies and international projects against third-party currency fluctuations can be expected. One might expect grander international infrastructure projects, especially ones that open up interiors or promise employment and new consumers. With regard to ASEAN-China relations, it might be expected that ASEAN will do more to encourage exports to China and Chinese investment in ASEAN. All of these activities are likely to enhance interest in the East Asia Summit, an ASEAN initiative begun in 2005, and the possibilities of a future East Asia Community.

Conclusion

In times of uncertainty the prudent strategy is to avoid risk. In the current era of global economic uncertainty negative effects are inevitable for both Vietnam and China because of the structure of their external trade. Nevertheless, Vietnam and China are not the cause of the current global instability, and if they rise to the challenges of the current crisis they will soon recover and prosper.

Beyond the immediate problems of inflation and industrial dislocation, Vietnam faces the challenge of redirecting its development efforts more towards its domestic markets and middle income states. The most accessible and promising market is China, and China also provides a model of how to expand trade opportunities elsewhere.

China is well positioned for the current crisis. It has already expanded its external and domestic markets and its finances are reasonably strong. China will benefit from earlier prudent strategies. Its major challenge is to prevent future crises by emphasizing sustainable development.

Fortunately for both countries, the Vietnam-China relationship is normal. This is especially vital for Vietnam, since China presents its greatest external opportunity. The relationship is also important for China, since normalcy is the foundation of mutual benefit. However, uncertainty heightens the sense of risk for the smaller country in an asymmetric relationship. Both global and regional institutions are important for buffering bilateral relationships. For China and Vietnam, ASEAN and ASEAN’s broader regional initiatives are likely to provide a useful framework for stabilizing bilateral interactions and supporting greater integration.

Brantly Womack is Professor of Foreign Affairs at the University of Virginia and author of China and Vietnam: The Politics of Asymmetry. [email protected]

Recommended citation: Brantly Womack, “Vietnam and China in an Era of Economic Uncertainty,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 36-2-09, September 7, 2009.

Notes

1 In purchasing power parity (PPP). In current dollars two percent. WTO Country Profiles April 2009.

2 Coal is a somewhat of an exception. Vietnam supplies one-third of China’s total coal imports, and two-thirds of its anthracite (hard coal) imports.

3 Vietnam News Agency, “Coal industry ups output to 43 million tons,” 23 July 2009.

4 China Statistical Yearbook 2008, Chart 17-8, “Value of Imports and Exports by Country.”

5 The first eight months of 2009 compared to the same period previous year.

6 See Mark Selden, “China’s Way Forward? Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Hegemony and the World Economy in Crisis,” The Asia-Pacific Journal.

7 International Comparison Project 2005, Global Purchasing Power Parities and Real Expenditures (Washington: World Bank, 2008).

8 Le Thi Thuy Van, “The Global Crisis and Vietnam’s Policy Responses,” East Asian Policy (April-June 2009), pp. 63-74, p. 71.

9 Ross Garnaut, “China’s Place in a World of Crisis,” in Ross Garnaut, Ligang Song and Wing Thye Woo (eds), China’s New Place in a World of Crisis (Canberra: Australian National University E-Press, 2009), pp. 1-14.

10 Calculated from data supplied by General Statistics Office of Vietnam.

11 IMF, “Vietnam – Informal Mid-Year Consultative Group Meeting,” Buon Ma Thuot, June 8-9, 2009.

12 Financial Times, “Thai Economy Emerges from Recession,” August 24, 2009.

13 General Statistical Office of Vietnam, “Imports and exports by country group, country and territory in first 6 months, 2009.”

14 Selden, ibid.

15 Calculated from China Statistical Yearbook 1999, 2002, 2007.

16 Brantly Womack, “Recognition, Deference, and Respect: Generalizing the Lessons of an Asymmetric Asian Order,” Journal of American East Asian Relations 16:1-2 (Spring 2009), pp. 105-118.

17 In November 2007 China set up a county-level administrative unit in Hainan with responsibilities for its territories in the South China Sea. There was a demonstration in Hanoi on December 9, prompting a public remonstrance from China, which was followed by a second demonstration on December 15.

18 “Vietnam Reportedly Set to Buy Russian Kilo Class Subs,” Defense Industry Daily, April 28 2009.

19 Brantly Womack and Gu Xiaosong, “Border Cooperation Between China and Vietnam in the 1990s.” Asian Survey 40:6 (December 2000), pp. 1042-1058.

20 The case is summarized in “Bauxite Bashers,” The Economist (April 23, 2009).

21 Alice Ba, (Re)Negotiating East and Southeast Asia: Region, Regionalism, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009).

22 China set a powerful example. Among many others, the EU and the US signed in July 2009.