By Bertil Lintner

There is nothing wrong or unusual about the food at Ang’s Chinese restaurant. In fact, the roast duck served there is excellent, and the Lonely Planet’s guidebook assures you that its hot-and-sour soup is special. It’s just the way the place looks. The yard is surrounded by high walls with razor wire and surveillance cameras. Two security guards watch the entrance and open the sliding gate only if customers, in their vehicle, appear to be genuinely wanting to have just a meal. Having satisfied the guards and parked the car inside the gate, lunch or dinner guests are met by another steel door guarded by more watchmen. They will not only shut the door but lock it once the guests are in the actual restaurant building. They guests may enjoy Ang’s oriental fare in peace.

Welcome to Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea-and, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit, the worst place to live among 130 world capitals and major cities. The hotel where I stayed had three armed guards outside the front gate, plus two huge German shepherd dogs. And then, needless to say, a high wall topped with razor wire, surveillance cameras and powerful spotlights at night. I was advised not to venture out on foot even in broad daylight, and this was one of the poshest areas in downtown Port Moresby.

Papua New Guinea’s notorious raskols-pidgin English for rascals-are everywhere. They are gangs of young men for whom crime has become a way of life. Having moved into Port Moresby from the highlands or elsewhere, they end up in shantytowns and suburbs where unemployment rates hover between 70 and 90 percent. And they were born into a culture where tribal warfare, vendettas and violence are deeply ingrained. Add the availability of firearms in urban areas, and it’s not surprising that most of Port Moresby’s homes resemble top security prisons.

It is also not hard to understand why many expatriates have left or are leaving. At independence from Australia in 1975, there were 50,000 non-citizens in the country. Now only a few thousand Australians, Britons and Germans remain. But, as the chatter in Ang’s restaurant indicates, newly-arrived mainland Chinese are replacing them as businessmen, contractors and importers-exporters. An article in a local newspaper said that “Australia has always considered Papua New Guinea its backyard [but]…since 2000, Papua New Guinea has increased its bilateral relations with China in areas of trade, investment and the military.” The article asserts that “China is here to stay.”

Many are here to stay permanently, as well. According to official estimates, there are about 10,000 Chinese citizens in the country. Many of them are here illegally, but Papua New Guinean passports, and therefore citizenship, are not difficult to obtain. Corruption is endemic at all levels in the government and local administration.

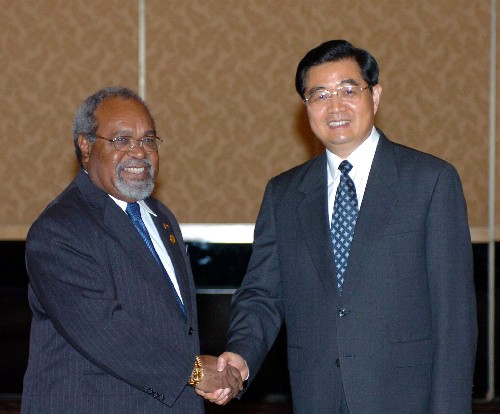

PNG Prime Minister Somare meets Hu Jintao

In addition, aid from China comes in handy when countries such as Australia threaten to cut their assistance because of corruption, nepotism and abuse of power in Papua New Guinea. “China’s rising status as an economic and military power is becoming an important pillar for developing countries like Papua New Guinea,” Tarcy Eri, a high-ranking foreign ministry official, said at China’s national day celebrations on October 1 last year. China’s voice at the United Nations, he said, was “one for the developing world.”

Besides the Russian Far East, and parts of Southeast Asia, such as upper Burma and northwestern Laos, the South Pacific – Papua New Guinea in particular – is becoming one of three areas on the world where Chinese influence is spreading so rapidly that it may soon make not only an economic but also a demographic difference.

The South Pacific is especially important for a number of reasons. One is that Taiwan has been trying hard to obtain diplomatic recognition from the impoverished island nations of the Pacific, amid Beijing’s drive to deny Taiwan its claims to legitimacy. Taiwan’s efforts always come with generous offers of aid, something that these resource-starved countries badly need. As a result, the Marshall Islands, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Kiribati, Nauru and Palau recognise “The Republic of China” – Taiwan’s official name – rather than Beijing.

But Beijing began to adopt similar tactics, funding government buildings in Vanuatu and Samoa. It paid for the construction of the venue of the 2004 South Pacific Games in Suva, Fiji. And China has invested heavily in Papua New Guinea, which is actually rich in natural resources but has been unable to attract significant investments from the West. Chinese aid to Papua New Guinea, the largest state in the Pacific, is now second only to that of Australia.

A shopping mall in downtown Apia, Samoa, owned by

a Chinese immigrant (top) and a Samoan government

office funded by the Chinese government.

But there is also something larger going on here in the Pacific. While the attention of the United States is currently focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China is making inroads into gaining influence in what has long been regarded as the U.S.’s home turf, the Pacific. Some analysts have even suggested that the ocean is becoming the venue for a new Cold War, wherein the U.S. and China compete for client states and strategic advantage.

Indeed, China is expanding its influence over the Pacific with the “long-term aim of challenging the United States as the prime power in the area,” says Benjamin Reilly, a senior lecturer at the Australian National University in Canberra. “It can no longer be taken for granted that Oceania will remain a relatively benign ‘American Lake’.”

Reilly notes that China now also provides military assistance to the few Pacific islands that maintain forces-apart from Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Tonga and Vanuatu. Tonga especially proves the point that Reilly wants to make about China’s long-term strategic interests in the Pacific. For years, Tonga was Taiwan’s staunchest ally in the Pacific. But in 1998, Tonga shifted recognition to Beijing. Its then-king (Taufa’ahau Tupou IV, who passed away now in September 2006) received a red-carpet welcome in Beijing along with promises of aid. Two deputy chiefs of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army have visited Tonga in recent years. Tonga may be tiny-no more than 100,000 people live on 700 square km-but it is strategically located, square in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Mohan Malik, a China analyst at the Asia-Pacific Centre for Security Studies, told me when I met him in Hawaii that increased Chinese tourism and migration are also part of Beijing’s “economic and strategic penetration of Oceania.” In recent years, thousands of Chinese have settled in the Pacific, running grocery stores, restaurants and other small businesses. The numbers are not significant in a global context, but both Reilly and Malik argue that Chinese migration into these Pacific states with their tiny populations has upset traditional ethnic and economic patterns. In the Tongan capital of Nuku’alofa, for example, there was not a single Chinese-owned grocery store 20 years ago. Now, more than 70 percent of them are owned by newly-arrived Chinese.

Many Chinese immigrants’ shops were looted

during riots erupting in Port Moresby, Papua New

Guinea during March 1997. Here, two employees

at a Chinese run shop begin to reorganize the

merchandise.

In Fiji, many ethnic Indians, whose ancestors were brought there by the British to work on sugar plantations more than a hundred years ago, have been forced to leave as ultra-nationalist Fijian politicians have assumed power. But the departure of the Indians, most of whom were businessmen and shopkeepers, has only created a vacuum that is being filled by Chinese immigrants. A stroll along Victoria Parade, the main thoroughfare in the capital Suva, is enough to see the growing influence of the Chinese. There are now as many shop signs in Chinese as there are in English, and more than in Hindi.

According to Reilly, the realization of China’s ambition to develop a blue-water navy, which it now lacks, would increase its interest in the Pacific even further. Now, despite recent developments, the region is not at the top of Beijing’s list of security priorities. Taiwan and the Spratly Islands figure much more prominently. But, as Reilly points out, China has seen how Japan and other countries have historically used the Pacific islands in the service of building a Pacific empire. Although there is no evidence that China will seek to expand its influence by waging war, it seems inevitable that its interests in the region will clash with those of the U.S. in the long term.

This article originally appeared at Hankyoreh on November 28, 2006. It is published at Japan Focus on December 5, 2006.

Bertil Lintner is an independent journalist. He is working on a book on Chinese migration to the Asia Pacific region. See his website.