Between 2012 and 2014 we posted a number of articles on contemporary affairs without giving them volume and issue numbers or dates. Often the date can be determined from internal evidence in the article, but sometimes not. We have decided retrospectively to list all of them as Volume 10, Issue 54 with a date of 2012 with the understanding that all were published between 2012 and 2014.

Statement of Opposition by The Japan Scientists’ Association

声明 日本政府の「主権回復・国際社会復帰を記念する式典」開催に反対する

Translated by Michiko Hase

Introduction by Matthew Penney

On April 28, a “Ceremony to Commemorate the Anniversary of Japan’s Restoration of Sovereignty and Return to the International Community” was held in Tokyo. As the Abe government makes plans to revise the 1947 constitution, this celebration of the anniversary of the end of the American-led occupation of Japan in 1952 took on a special significance. This brainchild of Abe and other far right conservatives is more than just an attempt at a Japanese “Independence Day”. It casts the Constitution as a foreign imposition and frames postwar reforms as an affront to Japan’s sovereignty and traditions.

While Abe has recently called into question whether Japan’s wars of the 1930s and 1940s were “aggression”, highlighting his view of the Tokyo Trial and postwar settlement as a form of “victor’s justice”, he is usually careful (or strategically vague) when discussing issues such as the place of human rights in the Constitution and the extent to which “tradition” should determine Japan’s legal foundation. Among his inner circle, however, are many who openly lash out at anything seen as a foreign imposition. Inada Tomomi, the Minister of State for Regulatory Reform in Abe’s cabinet, openly describes subscription to United Nations or international human rights conventions as violations of Japan’s culture. This is part of a pattern of rhetoric that sees the current Constitution as a foreign imposition holding Japan back that must be revised to give primacy to a conservative vision of “Japanese values”. Inada holds, for example, that gender equality laws should be decried as examples of outside pressure that threaten to undermine “traditional” Japanese gender and family norms (Bessatsu Seiron, July 2007). She understands “human rights” not as rights to self-realization and dignity, but the right to be “Japanese”, defined in conservative terms, free from the influence of outsiders. These views are outlined in the book Nihon wo shii suru hitobito (The Ones Who Murder Japan, PHP, 2008), the very title of which suggests that Japan is being “murdered” by those who would chip away at sovereignty, understood not only as territorial integrity, but also as cultural purity. As with Abe and his close supporters generally, there is no reflection on how state and sovereignty can be coercive. At present, far right conservatives believe that norms of sacrifice for the state, women in their “proper” place, military patriotism, and so on are a natural state of being for Japanese, only interrupted due to violations of Japan’s sovereignty – American-led occupation and the Constitution. This is why the “restoration of sovereignty” is celebrated and even fetishized. It represents a desire to return to the imagined purity of an earlier time, an imagination of a “true Japan” that Abe and others want to protect from the inconvenient history of aggression, massacres, violent coercion at home, brutal crackdown on dissent, the ills of modern capitalism, with vicious strikebreaking forgotten and “death from overwork” narrated as a facet of natural industriousness, discrimination, and endemic poverty in the shadows of “miracle” growth.

Not everyone is accepting the “Ceremony to Commemorate the Anniversary of Japan’s Restoration of Sovereignty and Return to the International Community” as a simple cheer for independence. The Asahi posited that the April 28 anniversary should not be a moment of celebration but rather an opportunity to reflect on past mistakes – the wars of aggression and imperial expansion that led to Japan’s 1945 defeat and loss of sovereignty. The Nikkei, not a progressive newspaper but rather one deeply wary of the potential impact of “history wars” on Japan’s trade relationships and economic partnerships, links attempts to commemorate the end of the US occupation to historical revisionists who borrow wartime idiom to describe the conflicts of the 1930s and 1940s as a “Holy War”. Shifting the moment of “freedom” from the fall of the militarist regime with defeat in 1945 to the end of occupation in 1952 reorients hitherto mainstream narratives of war and postwar. The Nikkei editors also suggest that the goal of this commemoration is to frame the 1947 Constitution as a foreign imposition. Progressives have long argued that whatever the constitution’s origins, it was embraced by a majority of Japanese people anxious to leave militarism behind. The “Ceremony to Commemorate the Anniversary of Japan’s Restoration of Sovereignty and Return to the International Community” places the Constitution instead as a form of outside violation.

The Nikkei also argues that in all this discussion of commemoration of the return of sovereignty, there has been little said about why Japan was occupied in the first place: “Was it that Japan had justice on its side but was defeated because of a lack of strength? Wasn’t it rather that Japan chose the wrong path?” In this case the Nikkei is opaque about just what the “wrong path” entailed, but nevertheless does a good job of contextualizing the current government’s historical views for its largely conservative readership. More committed progressive sources like the Mainichi Shimbun argued directly that education about Japan’s war record should be a necessary part of any commemoration initiative along with reflection on the fact that a repudiation of wartime militarism was an important part of Japan’s “return to the international community”.

Many are also pointing out that 1952 might represent the return of independence for Japan, but celebrating it is an insult to Okinawa which remained an American base colony lacking the protections of either the Japanese or American constitutions until 1972 and still suffers under a form of continued occupation as it is burdened with nearly three-quarters of the American base presence in Japan despite making up under 1% of the country’s area. A large-scale demonstration was held in Okinawa to coincide with the Tokyo celebration. One local told NHK “I have no idea why the government is holding a ceremony celebrating regaining sovereignty now. Thinking about the burden of the American bases, there is no way that I can say that we have recovered our sovereignty.”

For the far right, the ceremony was an occasion to raise “sovereignty” as an increasingly urgent contemporary issue. The Sankei Shimbun offered extensive coverage of the “Ceremony to Commemorate the Anniversary of Japan’s Restoration of Sovereignty and Return to the International Community”, showing the event’s appeal to conservatives. In an op-ed on the ceremony, the Sankei editors chose to evoke “restoration of sovereignty” in a very different way, however. “Recently, China has been aiming at seizing the Senkaku Islands and has been repeatedly violating the surrounding waters. What is more, a Chinese ship locked its firing radar on a Maritime Self Defense Force vessel. This is a moment of crisis in which Japan’s sovereignty is being violated.” In this case, the restoration of Japanese independence after WWII is being rhetorically paired with the contemporary island standoff with China. They also add, “Until we have taken back the Northern Territories and Takeshima and until all of the North Korea kidnap victims have been returned to Japan, there will be no true restoration of sovereignty.” This sets a confrontational international agenda as a natural outgrowth of any sovereignty discussion. Abe’s speech at the April 28 event frequently evoked “world peace” as one of Japan’s central aims, and while the Prime Minister stayed away from directly confrontational statements, the media sources that run closest to his views on history and contemporary geopolitics have used the event to heighten a sense of tension and of Japanese victimization at the hands of others, without reflecting seriously on how any of these territorial issues are to be resolved given splintered diplomatic relationships or on how kidnap victims in North Korea are to be “returned” now that relations have been almost completely severed.

Japanese conservatives are not in lock step, however. The Komeito has closely supported the LDP for a decade and a half as a conservative coalition partner. Party head Yamaguchi Natsuo was critical of the sovereignty ceremony, however, and was quoted by the Nikkei as saying, “The day on which Japan’s independence was recognized must be seen in the context of a Constitution that clearly puts sovereignty into the hands of the people. I question whether [the sovereignty ceremony] has really done enough to touch upon the significance of this.” While he does not go into detail about his doubts, if we read between the lines it would seem that Yamaguchi is concerned about just how “sovereignty” has been presented through this celebration. Is this praise of postwar democracy? Or does the celebration of sovereignty alongside talk of “duties” over “rights” by many elite conservatives represent desire to return to a system of emperor-centered patriotism that the occupation undermined?

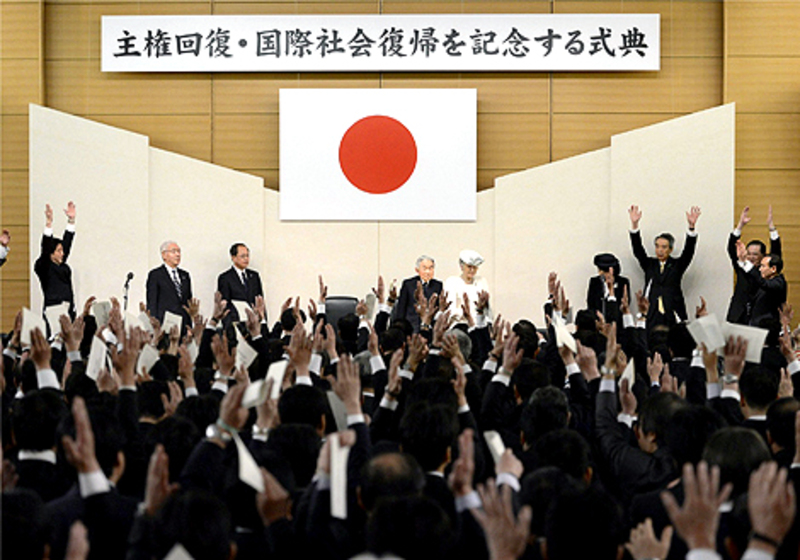

Along similar lines, the participation of the Emperor and Empress in the ceremony has sparked controversy. While the Emperor did not speak at the event, LDP lawmakers and other conservatives raised their voices in a shower of “banzai” calls to celebrate the imperial presence. This appears to have been spontaneous or at least unannounced. Critics see this moment as an intentional and horrifying evocation of prewar patriotism in the context of an event that bemoans the loss of sovereignty in defeat without consideration of the events that brought it about.

The “Banzai” moment

Below is a statement opposing the sovereignty ceremony by the Japan Scientists’ Association, a group of educators and researchers founded in 1965 which promotes critical reflection on the role of science and technology in society and particularly on the ties between the scientific establishment and the military. It outlines the major objections to the ceremony and the historical understanding that lies behind it.

Statement Opposing the Japanese Government’s “Ceremony to Commemorate the Anniversary of Japan’s Restoration of Sovereignty and Return to the International Community”

Translated by Michiko Hase

The Abe Shinzō Cabinet has decided to hold a “Ceremony to Commemorate the Anniversary of Japan’s Restoration of Sovereignty and Return to the International Community” on April 28.

No matter how the government explains its intent to hold the ceremony, there is no doubt that the ceremony will commemorate and celebrate the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the original U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, both of which took effect in 1952. We find the ceremony absolutely unacceptable for the following reasons.

First, to attribute Japan’s “restoration of sovereignty and return to the international community” to the San Francisco Peace Treaty diminishes the significance of the proclamation of the Japanese Constitution and other occupation-era democratizing policies that preceded the San Francisco Treaty. The Abe Cabinet has made a revision of the Constitution a priority, and the planned ceremony is nothing but the government’s attempt at advancing the formulation of a constitution to replace the existing one.

Second, China and the Koreas, victims of Japan’s war of aggression, were excluded from the San Francisco Peace Treaty, and the Soviet Union also was not a signatory. On the other hand, a U.S.-Japan Security Treaty went into effect along with the Peace Treaty, paving the way for Japan’s subordinate role in a military alliance with the United States. These two treaties have caused distortions in Japan’s internal and foreign affairs to this day, including the territorial disputes with its neighbors, its refusal to take responsibility for its wartime aggression against other Asian countries, and its discriminatory policies toward people from its former colonies.

Third, under Article 3 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, Okinawa, the Amami Islands, and the Ogasawara Islands were separated from mainland Japan and placed under dark U.S. military rule contrary to the postwar principle against territorial expansion. Japan drove these areas outside the bounds of the rule of law under the Japanese Constitution. In particular, Japan let the United States exploit Okinawa as islands of military bases, rob Okinawans of their land, trample their human rights, and use the bases as launching pads for the Vietnam War and other wars—these facts constitute the darker side of Japanese history that should never be forgotten. In Okinawa prefecture, April 28 is remembered as the “Day of Humiliation” and Okinawan people strenuously oppose the planned ceremony. In Amami, as well, a protest rally will be held on April 28. The government should heed the voices of those who were negatively affected by the Peace Treaty.

Fourth, Okinawa’s burden as “islands of military bases” is not a thing of the past but an ongoing pain. Throughout the postwar period when Japan supposedly “restored sovereignty,” the Japanese government has allowed the United States to use the military bases at will, depriving Okinawans of life and dignity. Moreover, the U.S.-Japan alliance system has been further strengthened, and there is mounting pressure to fortify the bases and the security system in the mainland and Okinawa, as exemplified by the proposed new base in Henoko. Japan’s dependence on the United States is deepening in all aspects of national policy, including the Transpacific Partnership.

Fifth, for reasons stated above, a broad spectrum of citizens, including historians and other experts, are critical of the system created by the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. To hold a ceremony that commemorates and celebrates this problem is nothing short of government imposition of a particular view of history on the entire nation. To have the emperor attend the ceremony, furthermore, clearly is a political use of the emperor prohibited by the Constitution.

The Japan Scientists’ Association is a scholarly body that defends the Constitution, engages in scientific research and education in history and other subjects, and seeks to contribute to the construction of peace and the happiness of the people. We therefore strongly oppose the “Ceremony to Commemorate the Anniversary of Japan’s Restoration of Sovereignty and Return to the International Community” that the Japanese government is planning to hold on April 28. The Japanese government has the responsibility to protect and apply the Constitution. In this regard, the Japanese government should make it a priority to correct the distortions brought about by the San Francisco Peace Treaty system described above, such as the complete removal of the military bases from Okinawa.

April 25, 2013

The Japan Scientists’ Association

WEBSITE – Japanese and English

Asia-Pacific Journal articles on related themes:

Alexis Dudden, Bullying and History Don’t Mix

Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Freedom of Hate Speech: Abe Shinzo and Japan’s Public Sphere

Herbert P. Bix, Japan Under Neonationalist, Neoliberal Rule: Moving Toward an Abyss?

Children and Textbooks Japan Network 21 and Matthew Penney, The Abe Cabinet – An Ideological Breakdown