Article summary: This article introduces Ikeda Manabu and his art, and situates his work within the history of imagining disasters in Japanese art by introducing prominent Japanese works, including disaster prints from the Edo and Meiji periods and nuclear art by Domon Ken, Fukushima Kikujiro, and Maruki Iri and Toshi. The article will ultimately consider what Ikeda’s art means to the larger discourse of contemporary Japanese society and art.

|

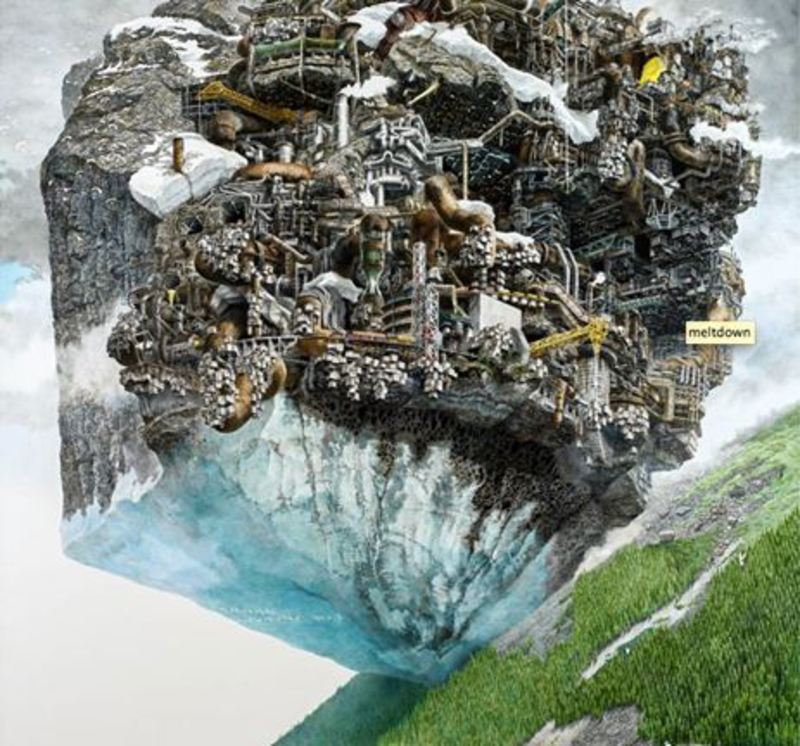

Ikeda Manabu, Meltdown, 2012. Pen, acrylic ink on paper mounted on board, 122cm x 122cm. Photo by West Vancouver Museum. Courtesy of the artist and Mizuma Art Gallery. |

Introduction

In January 2013, Ikeda Manabu released his latest work titled Meltdown at the West Vancouver Museum in Canada. By applying acrylic ink on paper with pen, the artist drew an incredible image that, with its concise, blunt, and even shocking title, unquestionably refers to the meltdown of three nuclear power plants at Fukushima Daiichi in Northeastern Japan after the earthquake and tsunami in 2011. A monumental iceberg-like entity, whose top comprises a gray-colored, dysfunctional industrial complex, is juxtaposed with the lively natural green forest and emerald blue sea beneath it. It will not be long until the “dead” industrial world touches and contaminates the natural worlds of trees and water through the bottom part of the iceberg. Meltdown invites the viewer to come closer to the work, to explore visual devices that the artist has set out. Ikeda’s craftsmanship and artistic skills are impressive: he meticulously draws the tiny, entangled pipes of the plant, renders individual trees with tremendous care, and presents the theme in an allegorical framework. Mirroring the practice of contemporary Japanese art, which consciously merges “subculture” (anime and manga) with “fine arts,” Ikeda incorporates into his art the fantastic world of the filmmaker Miyazaki Hayao, to whom, he publically acknowledges, his works are indebted. Meltdown is reminiscent of the old but energetic and living residential castle situated against a mountainous natural background in Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle (2004). Radiation is invisible, but Ikeda focuses on the “visible” symbol of the Fukushima nuclear meltdown: the plant. It is the uncontrolled, collapsed nuclear plant that made the nearby area uninhabitable, and Ikeda’s drawing, which is void of human figures, conveys the solitary atmosphere of this deserted part of Fukushima. The juxtaposition of the radiation-exposed broken nuclear plant and glorious, pure nature is disturbing and alarming, conveying to the viewer the urgency of the problems that Japan is both facing and causing for the rest of the world. “This time it occurred in Japan,” the artist says, “but there are hundreds of nuclear plants throughout the world, and you never know where an accident will occur next.”1 The audiences at West Vancouver Museum found Ikeda’s art disturbingly relevant.

|

Meltdown reminds us that after nearly two years the Great East Japan Earthquake continues to haunt us. This work is the artist’s first direct engagement with contemporary social and political issues. Ikeda’s art without question adds a new chapter to the long history of disaster / nuclear art in Japan. The question is, what kind of chapter will that be? This article will first introduce Ikeda Manabu and his art, and situate Ikeda’s works within the history of imagining disasters in Japanese art by introducing prominent Japanese works, including disaster prints from the Edo and Meiji periods and nuclear art by Domon Ken, Fukushima Kikujiro, and Maruki Iri and Toshi. The article ultimately considers what Ikeda’s art means to the larger discourse of contemporary Japanese society and art.

Ikeda Manabu

Ikeda Manabu is one of the most successful Japanese contemporary artists (see more works by Ikeda here). He was born in Saga, southern Japan, in 1973 and earned his BA and MA from the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. Working primarily with pen and acrylic paint, he has produced fascinating works that are extremely detailed and combine the human and natural worlds, the past and the future into a single pictorial field. Many of Ikeda’s works intertwine elements of history, culture, nature, and cityscape. His themes and subject matter are monumental but Ikeda draws intricate buildings, people, trees, animals, birds, trains, ships, and planes. Because of the intensity of his work, most of his drawings are small in size, but he has created several large-size works, each taking more than a year to complete. His artworks are arresting and entertaining, full of visual devices that create unexpected connections between disparate scenes. His works compel viewers to “read” them carefully and remember the joy of looking.

At the same time, there is an alarming, dystonic tone in his art: human figures, which are always tiny and anonymous, have no control over the overwhelming power and scale of nature. His Lighthouse (2009), for example, depicts a gigantic lighthouse, which is so old that trees grow out of it. Pummeled by stormy sea waves, it is falling over. Numerous white birds that fly over the lighthouse, perhaps shocked by the weather and the fall of the lighthouse, add an element of drama to the picture. The human and natural worlds maintain an intricate balance of power, but Ikeda’s man-made objects, like the lighthouse, cannot always predict or endure the forces of nature. Predominantly drawn in blue and navy, the tone of the work is dark, and highlights the menacing, untamable side of the natural world.

|

|

Ikeda’s works are in the collection of the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, one of the largest contemporary art museums in Japan, and in the private collection of Takahashi Ryutaro, a very prominent collector of contemporary Japanese art in Japan. His works have also been exhibited in major international group exhibitions, including Re-Imagining Asia (2008, The House of World Cultures, Berlin), Great New Wave: Contemporary Art from Japan (2008, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario), and, most recently, Bye Bye Kitty (2011, Japan Society, New York). His Existence (2004), a large-scale drawing of a humongous tree comprising many separate, uniquely shaped trunks intertwined into one, was selected as one of the best artworks of 2011 by the New York Times, establishing Ikeda without question at the pinnacle of the contemporary Japanese art world (link).

|

|

Since 2011, Ikeda has resided in Canada. He spent a year in Vancouver on a fellowship provided by the Japanese government’s Agency for Cultural Affairs in 2011. He chose Canada to benefit his art. He was particularly interested in Vancouver’s cityscape situated in a natural landscape, and he acknowledges that life in Canada has affected his work, especially in regard to how to conceptualize space. Ikeda now renders the gap between objects more expansively, often incorporating monumental space into his visual field. For instance, he fills the entire space of the paper in Lighthouse and leaves white, unfilled spaces in Existence, but in Meltdown, which he executed in Canada, he uses the space surrounding the nuclear plants more creatively. The bottom portion of the work is rendered into natural landscape, which interfaces with the main subject of the power plant, adding context and dynamism to the picture.

When the Great East Japan Earthquake took place, Ikeda was in Vancouver. He learned about what was happening through the Internet and the Canadian media. His decision to continue living in Canada after his fellowship ended was partially to protect his young daughter’s health. The artist also believes that he would forget about the disaster if he lived in Japan. He thinks that people in Japan are, understandably, eager to get past the traumatic event, often at the risk of ignoring radiation exposure problems and other threats posed by the crippled nuclear plants in Fukushima Daiichi. Ikeda needs distance from Japan, for the moment, to keep “fresh” the memories of the anxiety and insecurity he felt being away from home during the disaster. In preparation for creating works related to the disaster, however, Ikeda made a trip to the Tohoku area in February 2012, visiting Kesennuma and Rikuzen Takada, to see the actual site of the disaster with his own eyes.

Ikeda has an interesting story about why he decided to produce drawings related to the Great East Japan Earthquake. The artist created a work titled Foretoken (Yocho in Japanese) in 2008, which depicts a large sea wave, and many of Ikeda’s friends and colleagues came to associate it with the 2011 disaster. After the devastating tsunami, some even called him “a prophet” (yogensha). Foretoken depicts people skiing on the surface of a building, a bodhisattva-like figure on a bear’s back chanting a Buddhist sutra, skeletons in a wrecked airplane, and a group of people “rock-climbing” the wave. All these human figures and cultural and technological products are swallowed by one big wave. The work reminds us of ukiyo-e artist Katsushika Hokusai’s masterpiece “Great Wave off Kanagawa,” which was executed in the early nineteenth century and is part of Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. Both works are powerful images of strong sea waves, but while Hokusai’s wave frames Mt. Fuji and provides a dynamic context to the mountain that symbolizes Japan, in Ikeda’s work, the wave itself is the sole subject and it is crowded with cityscapes, human figures, animals, and trees, creating a sense that human civilization is being completely overturned by the force of the wave. He did not set out to produce an image of a tsunami, however. As the artist states, he initially wanted to draw snow, but he started thinking that anything white would do, and it did not have to be snow. He then developed an image of a large wave swallowing civilization. The title Foretoken also seems uncanny, but Ikeda meant it to allow space for ambiguity. He says, “You never know if omens refer to something good or bad.” Despite the lack of intention to depict a disaster in Foretoken, however, as somebody who “predicted” it, Ikeda feels “obligated” now to create works that are about the Great East Japan Earthquake.

|

|

Disaster Prints: Edo and Meiji

As Japan is vulnerable to various kinds of natural disasters, visual artists have made them a subject of their art throughout Japanese history. We can trace the genealogy of disaster art to catfish prints (namazu-e) of the Edo period, which were produced in response to a magnitude 7.0 earthquake that hit Edo, today’s Tokyo, on November 11, 1855. This earthquake, together with the 1854 Ansei-Tokai Earthquake and the 1854 Ansei-Nankai Earthquake, is known as the Ansei Great Earthquake, and it killed more than 7,000 people.2 Namazu-e are woodblock prints published and circulated immediately after the disaster and allegorical pictures representing the Japanese folktale that earthquakes are caused by a giant catfish living beneath the country.3 As a result of publication censorship imposed by the Tempo reforms (1841-43), which made depictions of contemporary events illegal, namazu-e were usually unsigned, and their production was in fact banned after two months. Namazu-e interestingly encompass various interpretations of the disaster. Some believed that the earthquake was a form of divine punishment of Edo, which had flourished excessively. Others perceived the earthquake positively as a kind of “world renewal” (yonaoshi) which would trigger a redistribution of wealth, revitalize the economy, and bring about social reform. As a whole, namazu-e acted both as entertainment and social satire/critique. The print reproduced here and titled Blessing in Peaceful Times, for example, shows a personified catfish in the lower right, beaten by Edo commoners who were adversely affected by the disaster. At the same time, there are two men near the middle of the picture who try to stop the mob. These are tile dealers who benefited from the reconstruction after the earthquake. The title of the print reinforces the sense that the earthquake facilitated economic activity.

|

|

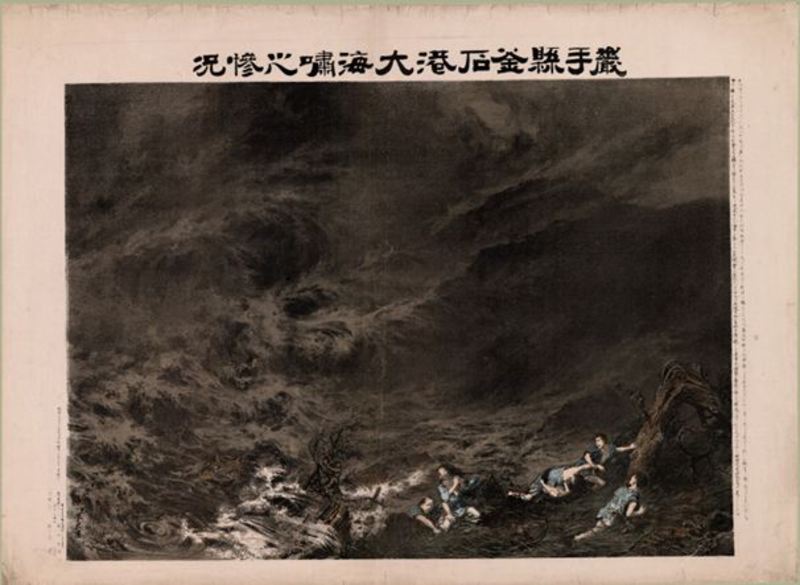

Woodblock prints on the 1896 Meiji-Sanriku Earthquake published in newspapers (kawaraban) form another prominent collection of disaster art. The Meiji-Sanriku Earthquake was a magnitude 7.2 earthquake that hit northeastern Japan on June 15, 1896. The earthquake itself did not cause much damage, but the tsunami that followed it proved devastating. It was as high as 38.2 meters and killed over 20,000 people, mostly along the Sanriku coast of Iwate and Miyagi prefectures in the Tohoku region.4 It should be noted that these are among the places that were hit by the tsunami following the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, and that the height of this tsunami exceeded that of the 1896 Meiji-Sanriku Earthquake. Unlike the Edo catfish prints that occasionally parody the disaster and the following social situation, the kawaraban prints convey the ferociousness of the event by illustrating the catastrophic effect of the tsunami. At a time when photograph and video were not available to capture the very moment of the disaster, these prints proved to be a valuable visual record with significant news value. One of the prints produced after the disaster, now in the George Beans Collection at the University of British Columbia, shows a tsunami hitting the coastal town of Kamaishi, Ishikawa Prefecture, which is known for its fishing industry. It captures the plight of a group of residents, who try to climb up a hill, followed closely by the great wave. Tiny human figures in the right foreground are contrasted with the infinite size and formlessness of the wave. The utter darkness of the sea and sky that dominate the picture captures a dramatic moment of the horrifying scene, highlighting the desperate situation of the people depicted. The printmaker might have been familiar with late 18th and early 19th century European Romantic paintings that explore dramatic phenomena of nature and human’s emotional reaction to them.5

|

|

Nuclear Art in Japan

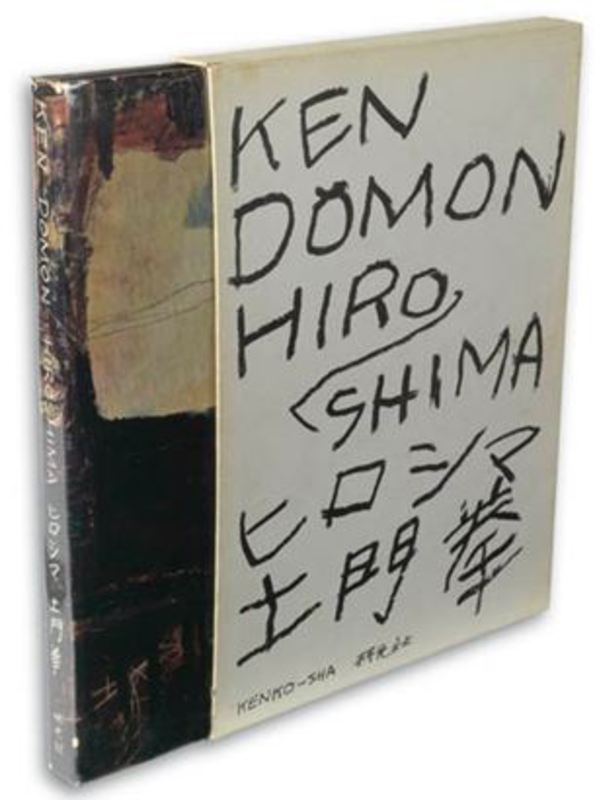

Ikeda’s Meltdown is one of the first direct artistic responses by a prominent Japanese artist to the Fukushima nuclear meltdown, but there are predecessors who have produced what we might call “nuclear art”: art related to the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. One of the best-known examples is Domon Ken’s photographic collection titled Hiroshima, which was shot in 1957 and published by Kenkosha in 1959. Domon captured images of victims undergoing painful surgery at the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital and suffering from burns and scars, and orphans cheerfully playing at the Hiroshima Municipal School for War Victims. Domon confronts the viewer with photographic evidence of their continuing pain and suffering, presenting human bodies that are grotesque, abject, deformed, and severely injured. Domon’s photographs are certainly disturbing, and they are even traumatizing to look at. Hiroshima was part of the photographic “realism” movement that Domon advocated in the early 1950s and disseminated through his writings and photo competitions in the magazine Camera.6 Unlike prewar (often avant-garde) photography that only pursued aesthetic qualities and was accessible to only a small number of people, Domon promoted photographs that represented the “reality” of the majority of Japanese people in the postwar period, seeking to make photography relevant to larger audiences.

Domon’s ultimate goal was to increase awareness of the nuclear-exposure in Hiroshima and its human costs, which the artist considered to be the national responsibility of the “Japanese” photographer. His language was often clearly imbued with nationalism, and he contributed to Japan’s postwar representation of itself as an absolute victim, that suffered from American-caused nuclear atrocity.7 Never critically reflecting on his own complicity with the wartime state, mainly through his participation in NIPPON, Japan’s propaganda magazine targeted at foreign audiences, he failed to acknowledge the aggressive and violent aspects of Japanese modern history, especially during Japan’s colonial period and World War II.

Photographer Fukushima Kikujiro also produced nuclear art. Fukushima was initially an amateur photographer who got his start through Domon’s realism movement. As Yuki Tanaka’s article in Japan Focus discusses (link), however, Fukushima’s approach to Hiroshima victims and his political agenda were very different from those of Domon. Fukushima developed a deeply personal relationship with Nakamura Shigematsu, who was suffering from lethargy sickness and occasional seizures caused by the illness. Unlike Domon Ken, who valued the formal elements of a photograph in addition to its social meaning, Fukushima paid less attention to his photographs’ aesthetics than to their politics. Furthermore, while Domon sought to present Hiroshima as a uniquely Japanese experience, Fukushima’s photographs highlighted the ethnic diversity and social inequality among the hibakusha. For example, the artist took photographs of Motomachi, a slum filled with atomic-bomb victims, including Koreans, who had been excluded from subsidized medical care.

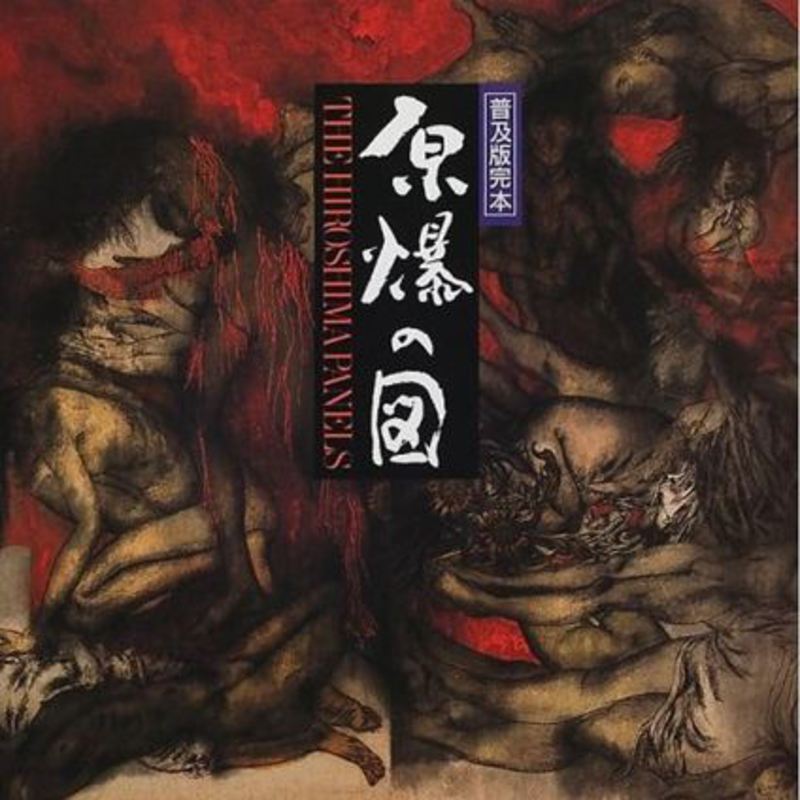

Probably the best known Japanese nuclear art internationally is The Hiroshima Panels, a series of fifteen panels painted by husband-and-wife artists Maruki Iri (Japanese-style painter) and Toshi (Western-style painter) beginning shortly after the war until 1982 (To see the Marukis’ work online, go to the museum website).8 The artists’ method of producing works of art was unique; they jointly produced paintings, one continuing to paint directly where the other left off the previous day. The completed paintings thus combine the impressionistic qualities of Iri’s ink dilution and Toshi’s careful rendering of human figures. As part of the Hiroshima Panels, the artists painted Ghosts I, a panel depicting the aftermath of the atomic bomb, which they witnessed when they visited Iri’s family in Hiroshima a few days after the bombing. Because the SCAP (Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers) prohibited the use of the word genbaku (atomic bomb) in public, the artists initially displayed this work under the title August 6, the date of the bombing of Hiroshima.

Deformed, fragmented naked human bodies, most of them women and children, emerge out of the black smoke in one of the panels, Ghosts I. Here, almost everything is colorless; bodies have become ashes and ashes cover bodies. Masses of people are walking, while some are lying on the ground and others are praying. All fifteen panels convey a sense of total confusion in scenes that cannot be comprehended as a cohesive narrative. A person covered with a blanket stares at a man who is about to kill another man with a sword. Amid the smoke, girls helplessly gaze at viewers beyond the panel, sitting and holding each other. They are not only witnessing the moment when their friends and families were blown away by the radioactive blast (neppu), but are also witnessing this historical moment of unprecedented nuclear catastrophe. The Hiroshima Panels evoke silence, a speechless moment of chaos. With no background, the specificity of the peoples’ experiences becomes ambiguous, and the painting represents Hell and human suffering. The Marukis actively participated in leftist political activities and considered their art as a means to convey issues of social inequalities and injustice, as did Reportage painters of the 1950s such as Yamashita Kikuji and Ikeda Tatsuo. And in direct contrast to Domon, they acknowledged the violence the Japanese army perpetrated against other Asians in The Nanking Massacre of 1937, representing Japanese soldiers as the aggressors.

The legacy of Hiroshima in the discourse of Japan’s postwar nuclear policy is complicated. While one might assume the city of Hiroshima, having experienced the atomic bomb, would have opposed the nuclear power industry, this was not the case. In fact, as Yuki Tanaka reveals, Hiroshima was an early supporter of the non-military use of nuclear energy, and the city hosted “The Peaceful Use of Nuclear Energy” exhibition in 1956, with sponsorship from institutions including the Hiroshima City Council, Hiroshima Prefectural Government, and Hiroshima University (link).9 Through these institutions, Hiroshima residents expressed the hope that precisely because they had suffered from the atomic bomb, they wanted to promote nuclear energy. Ironically, whether nuclear plants use atomic energy “peacefully” or not, following the 2011 nuclear meltdown, residents in Fukushima are now confronted by the same problems related to radiation that victims in Hiroshima and Nagasaki experienced sixty-six years earlier. Yet both the connection between Fukushima and Hiroshima/Nagasaki, and the contradictory history of postwar Japan as anti-nuclear-bomb but pro-nuclear-energy have been suppressed in public discourses. One example is an exhibition titled Genbaku wo miru [Viewing Atomic Bombs], which was to display art related to the atomic bombs including the Hiroshima Panels at Meguro Museum between April and May in 2011, which was cancelled, to the regret to many people. The museum announced that the cancellation was due to sympathy for people in Fukushima, but it is easy to see how the museum might have also cared about “Japan’s Nuclear Village,” powerful pro-nuclear advocates who benefit from nuclear industries and who try to minimize the scale of the nuclear crisis and the seriousness of the damage that it is causing to both humans and the environment (link).10 Nuclear issues have once again become taboo, as they were during the postwar occupation. But despite this fact, Japanese artists continue to extend their rich history of nuclear art, the art about human suffering from illness and injuries resulting from radiation exposure.

Epilogue

In addition to Meltdown, Ikeda is planning a large-scale drawing on the theme of Japan’s reconstruction after the Great East Japan Earthquake, adding to the Japanese visual-culture history of the disaster. This particular work, which at 4m x 3m will be the largest in his oeuvre, Ikeda estimates, will take three years. He will begin later in 2013 after he moves to Madison, Wisconsin where he will be an artist-in-residence at the Chazen Museum of Art. At the museum, he may show the production process to the public, and a film crew may document it. The artist speculates that just as life in Canada affected the work he produced there, life in Wisconsin may affect this work, but he does not yet know exactly how. Ikeda has been thinking carefully about this work for the past two years, and he already has a vision for it. The way a new tree trunk grows out of an old stump and how a new branch comes out of an old trunk, which he observed in Canadian forests, for example, have made him appreciative of the sheer power of life and the multi-generational life of organisms. It led him to believe that although Japan has been devastated by the disaster, there is always hope for life. For this work, he also says that he is increasingly interested in borrowing the forms of mythical animals, such as the Shinto-inspired serpent Yamata no Orochi. His reference to mythological creatures reminds us not only of the namazu-e (catfish images) of the Edo period, but also of the uranium sculptures of ants by Ken + Julia Yonetani, inspired by traditional aboriginal tales of dreaming in Australia. It reminds us that humans are not the only inhabitants of the Earth and its natural environment.

So what is Ikeda adding to the Japanese artistic history of disaster and nuclear images? What does his art mean to Japanese society at large? Ikeda’s recent works related to the 3.11 disaster may signal the arrival of what one might call “post-Murakami” art, the idea that David Elliot articulated in his exhibition Bye Bye Kitty!! Between Heaven and Hell in Contemporary Japanese Art (link). The exhibition began a week after the Great East Japan Earthquake, and featured works by sixteen mid-career artists, including Ikeda. Elliott’s proposition is that unlike Murakami Takashi’s “superflat” art, which represents Japan as a child and highlights the shallowness of public discourse in Japanese commercial culture, the emerging artists deal with serious, existential issues in their works. The exhibition was of course organized before the disaster, but several social movements were beginning to emerge then that resonated with the exhibition. Since the explosions at the nuclear reactors in Fukushima Daiichi, tens of thousands of citizens have participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations in front of the National Diet in Nagatacho. For the first time since the 1960 Anpo struggle and the 1960s anti-Vietnam War Beheiren movement, “average” citizens, including students, housewives and businessmen, who are not affiliated with particular political parties or ideologies, have protested to the government. Ikeda is thus one of many Japanese who decided not to withdraw from society or reside in the “super-flat,” infantile, virtual world of manga and anime. With Meltdown and forthcoming work, the artist seeks to address the urgent issue of environmental damage and celebrate the resilience of victims in Japan who are reestablishing their lives completely from scratch.

At the same time, his attitude toward politics is decidedly different from that of the creators of Hiroshima-related art of the 1950s and 1960s. While Domon, Fukushima, and the Marukis had clear political agendas, Ikeda does not directly associate himself and his works with the anti-nuclear demonstrations. This is a contrast to other cultural figures, such as Nobel Prize-winning author Oe Kenzaburo and Academy Award-winning musician Sakamoto Ryuichi. “I might be too ‘cool,’ but I do not believe that my art has the power to change the world,” he says. Ikeda is from a younger and more detached generation, the “post-Murakami” generation. It is too early to assess the impact of his disaster-related art on either Japanese contemporary art or society, but I am eager to see how the emerging Japanese artists might differentiate themselves from Murakami Takashi and form other artistic discourses.

Asato Ikeda earned her PhD from the University of British Columbia and co-edited, with Ming Tiampo and Aya Louisa McDonald, Art and War in Japan and its Empire: 1931-1960 (Leiden: Brill, 2012). As the 2012-2013 Anne van Biema fellow at the Freer | Sackler Galleries of the Smithsonian Institution, she is currently working on a monograph tentatively titled Soldiers and Cherry Blossoms: Japanese Art, Fascism, and World War II.

Recommended Citation: Asato Ikeda Ikeda Manabu, “The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, and Disaster/Nuclear Art in Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Volume 11, Issue No. 13, No. 2, April 1, 2013.

I would like to express my gratitude to N. J. Hall, Maiko Behr, Shirin Eshghi and Katherine Berry-Kalsbeek, who provided editorial help.

1 This article is based on an interview with Ikeda Manabu that I conducted in November 2012. I express my gratitude to the artist who kindly shared with me the vision of his art.

2 Noguchi Takehiko, Ansei Edo jishin: saigai to seijikenryoku [The Ansei Edo Earthquake: Disaster and Political Power](Tokyo: Chikuma shobo, 2004).

3 For more on namazu-e, see Cornells Ouwehand, Namazu-e and Their Themes: An Interpretative Approach to Some Aspects of Japanese Folk Religion (Leiden: Brill, 1964). Hidemi Shiga, “The Catfish Underground: Japan’s Earthquake Folklore and Popular Responses to Disaster,” Orientations 37. 3 (2006).

4 Yamashita Fumio, Sanriku Otsunami [Sanriku Great Tsunami](Tokyo: Kaede shobo, 2011).

5 I do not discuss arts and visual culture of the 1923 Tokyo Earthquake here, as Gennifer Weisenfeld has just published an excellent book on this subject. Gennifer Weisenfeld, Imaging Disaster: Tokyo and the Visual Culture of Japan’s Great Earthquake of 1923 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

6 Julia Adeney Thomas, “Power Made Visible: Photograph and Postwar Japan’s Elusive Reality, Journal of Asian Studies 67. 2 (2008): 382-386; Frank Feltens, “‘Realist’ Betweenness and Collective Victims: Domon Ken’s Hiroshima,” Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs (Summer 2011): 64-75.

7 For more on discourses about Hiroshima, see Lisa Yoneyama, Hiroshima Traces: Time, Space, and the Dialectics of Memory (Berkeley: The University of California Press, 1999).

8 Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi, The Hiroshima Panels (Saitama: Maruki Gallery for The Hiroshima Panels Foundation, 2004); John W. Dower and John Junkerman, The Hiroshima Murals: The Art of Iri Maruki and Toshi Maruki (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1985).

10 Jeff Kingston, “Japan’s Nuclear Village.”