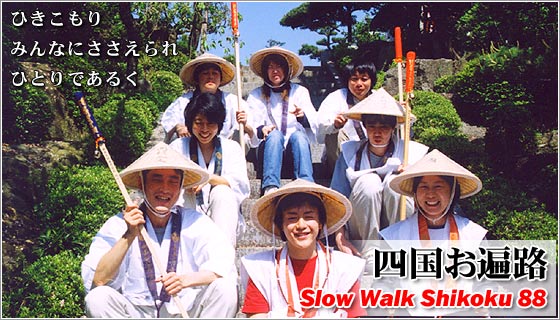

A Dialogue between Asano Shirou and Futagami Nouki

Translation by John Junkerman

Hikikomori is a Japanese term that, like sushi and sake, or more to the point, hibakusha, has entered the world lexicon. It refers both to the phenomenon and the individuals who suffer from “acute social withdrawal,” defined by the Japanese government as youths who isolate themselves in a single room of their parents’ home for six months or more. Estimates of the number of hikikomori vary widely, from several hundred thousand to over a million, but there is no denying that it is a major, and growing, problem confronting contemporary Japanese society. Most of the hikikomori are teenagers, eighty percent of them male, who often begin by refusing to go to school and then cut themselves off from social interaction entirely.

Hikikomori. Photograph by James

Whitlow Delano

A parallel phenomenon is the growing population of NEETs: (again by government definition) young, unmarried people, between the ages of 15 and 34, who are Not in Employment, Education or Training. This population has also been rising rapidly over the last decade and is now estimated at some 850,000. For whatever reason, these young people have fallen off the education-employment escalator and are not trying to climb back on. Instead, they continue to live with their parents or with their parents’ financial support, often mimicking the social withdrawal of the hikikomori.

Photograph by James

Whitlow Delano

These two phenomena are striking indicators of the breakdown of the ability of Japanese society to nurture its youth and absorb them into productive employment. They are deeply troubling, not only to the parents of these young people, but to a country that has prided itself on the efficacy of its educational system and the superlative performance of its corporate model.

Governmental responses to what is by all rights a social crisis have been slow and largely ineffective. The task of coming up with innovative solutions to these problems has been left to the nonprofit community. Futagami Nouki, the leader of one of these nonprofits, joined in a dialogue with former Miyagi Prefecture governor Asano Shirou in the September 2006 issue of Sekai magazine.

Futagami Nouki is the director of New Start, a nonprofit organization that supports troubled young people (hikikomori, school refusers, and economic dropouts) in making a new start in life. He is the author of Kibou no NEET (NEET Hopes).

Asano Shirou, a professor in the Faculty of Policy Management at Keio University, was the governor of Miyagi Prefecture for twelve years until 2005. He is the author of Shissou 12-nen: Asano Chiji no Kaikaku Hakusho (The 12-year Sprint: Governor Asano’s Reform White Paper) and numerous other books. This dialogue is one of a series hosted by Asano in Sekai magazine.

Translated by Japan Focus associate John Junkerman, a documentary filmmaker based in Tokyo. His latest film is the award-winning Japan’s Peace Constitution. The film addresses the constitution and its revision, featuring interviews with historian John Dower, political scientist Chalmers Johnson, and sociologist Hidaka Rokuro, as well as writers and historians from Korea, China, and the Middle East. The English version of the film is available from First Run Icarus Films.

* * *

Asano: Futagami-san, compared to someone who’s led a proper life like me, you’ve had a very checkered life (laughs).

Futagami: “Checkered” may be overstating it (laughs), but I was born in 1943 in the Korean city of Daejeon and I was repatriated to Ehime at the end of the war, when I was two and a half-years old. I was a refugee. In a sense I remained a displaced refugee and have identified with social refugees, on a journey that has brought me through 63 years.

Asano: There was an incident in high school…

Futagami: In my second year of high school, I was expelled. It was a private school in Matsuyama, a combined junior and senior-high prep school, and I had doubts about the assumption that everybody should be aiming for the University of Tokyo. For a year, I turned in blank answer sheets during exams, and then I was expelled. At 17, I was a high school dropout refugee.

After a while, a rural public high school took me in. But I rebelled there too, and one day I was called in to see the principal, fully prepared to be expelled again. But the principal was dressed in work clothes, and he said to me, “I’m going to plant some trees, Futagami, lend a hand.” I had come ready to argue about being expelled, but instead I found myself diligently digging holes and planting tree after tree in a corner of the schoolyard (laughs). Then, “All right, we’re finished. I just want to tell one thing I want you to remember,” he said. What he told me was, “To plant a tree is to plant virtue.” Then he suspended me for two weeks. If I had continued to be obstinate then, I’m sure I would have been expelled. But this was a broad-minded response from an adult. I’m grateful for this profound lesson, one that has continued to teach me throughout my life. On account of being expelled, I was able to encounter an adult.

Asano: Did you mend your ways when you got to Waseda University?

Futagami: Not in the slightest. I hardly attended class at all, but the one thing I do remember is from a class in the principles of political science. It was a lecture on the idea that wherever there are two or more people, there is politics, there’s politics between a married couple, or between a parent and a child. When I look at my own family, or at family-related problems in Japan today, I’m convinced that that principle gets at the heart of the matter (laughs). Actually, when I was 19 and still a college student, I opened a cram school in Matsuyama and ran it until I was 35.

Asano: Did it succeed as a business?

Futagami: At the time, there were no other cram schools, so it thrived without any difficulty. I had pockets full of money in my twenties, went out on the town every night. By the time I quit, the school had three thousand students. I had become a businessman, which bored me to tears. So I turned the school over to a successor.

Asano: What a waste. After that, what?

Futagami: I decided to start all over near Tokyo. I looked through my New Year’s cards and chose the place where I knew the fewest people, Chiba Prefecture. That’s where I went.

Asano: Did you have something in mind that you wanted to do?

Futagami: No, I was a 35-year old NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) refugee. I didn’t know what to do. I had a family, and we got by on my savings from the cram school.

Asano: An elite NEET…

Futagami: Actually, I was frantic. I started my second life too early, and ended up spinning my wheels for fifteen years. Finally, when I was 50, I learned about Miyakawa Hideyuki and his wife Maria Luisa Bassano through a documentary on NHK. It was a report about how they were creating an integrated welfare community in Italy. This was something that I had been thinking about, and here they were already doing this, in Tuscany. So I went to visit them.

Asano: What was the NHK documentary about?

Futagami: It described how four families were reviving a run-down vineyard and olive orchard using organic farming methods. When I visited the Bulichella farm, I found that there were psychologically disabled people working there. Italy closed its psychiatric hospitals some 35 years ago, and under this policy, psychiatric patients were placed in a variety of situations, where they are visited once a week by doctors for treatment. The farm was also in the process of proposing to the government that, instead of locking up youths in detention centers, their rehabilitation would be more successful if they were working on the farm in a loving environment.

Bulichella estate and vineyard

In Italy, it’s hard to survive on farming alone. When farms take in psychiatric patients, they are paid money that would otherwise have been paid to hospitals through medical insurance. But the cost of caring for these patients is far less than in a hospital, so that helps the government. Now they were going to take on youths from detention centers. For the government, this reduces costs and the result is fiscal reform. The three pillars of agricultural, educational, and welfare activities carried out at the Bulichella farm provided the original model for the integrated welfare community.

Sending Japanese Youths to the Italian Farm

Asano: Did you stay at the farm for a while?

Futagami: Back in 1993, I spent a month there. The next year Miyakawa proposed a project that would take in some Japanese young people. The farm could only manage seven at a time, so it would be a small project, but a dynamic one that could be promoted in Japan. Over the next six years, we sent a total of eight groups.

Asano: What kind of kids did he propose you send?

Futagami: At the time, it was young people who had lost their direction in life. Hikikomori and NEET kids, social refugees.

Asano: It must have been difficult to find the kids.

Futagami: Miyakawa set the condition that his actual costs would be covered, so the program was expensive, 1 million yen (about $8500) for two months. We asked newspapers to run a notice, but they refused because of the high cost of the program. Finally, a friend at the Yomiuri Shimbun wrote a short article. That morning the phone rang off the wall. We got forty calls in one day.

Asano: So you actually had competition to get into the program.

Futagami: That’s right. I realized how much the contradictions in Japanese society and families had built up, and how the number of social refugees had risen. There were eighty applications for the seven slots. To keep our effectiveness high, my inclination was to eliminate the kids who were sick and skip the kids who were high-risk delinquents, essentially to weed out those with low potential, like an exam does. But then I got a call from Italy, with Marisa on the other end, scolding me in Japanese: “Futagami, just the easy kids, there’s no point!” I was stunned. I had succumbed to the Japanese disease.

Asano: She wanted you to send the hardest cases.

Futagami: I didn’t have a plan, so I told those who came to an introductory meeting, “I’m just going to toss the applications in the air and the ones that fly the farthest will go.” A number of kids started to cry. They are kids who can’t adapt to the competitive society, right? And they came to this meeting filled with anxiety that they would be subjected to selection, like in an entrance exam, and they would be failed. So when I said, “The ones who fly farthest will go,” it was as if they were suddenly freed from that trauma. I was shocked at how stressful a position Japanese kids have been placed in.

Asano: They cried from a sense of relief at being released from that.

The New Start Program

Futagami: After two months, the kids would come back to Japan, and many of them had difficulty making a soft landing in Japanese society. I’d get calls from parents, saying their kid came back so strong, but now they’ve gone back into seclusion. I had no choice but to look after them, and after that it was a slow slide…

Asano: They were asking for aftercare.

Futagami: Right. I always think I won’t be the one to do it, but my life’s been like a quagmire, where I’m dragged into dealing with the problems of social refugees, like dancing with a bear (laughs).

Asano: What projects are you involved with now?

Futagami: Now it’s more than a project, we’re trying to build a new integrated community, with about 120 people, in the Gyoutoku district of the city of Ichikawa in Chiba Prefecture. It’s now about forty percent completed. It’s an urban version of what the Miyakawas are doing in Italy. Some seventy of the people in the community are NEET and hikikomori young people.

Asano: How many people are involved in the care giving, and who are they?

Futagami: There are fifty fulltime staff members, but a minority are professionals. I often refer to the “runaway wives and bankrupt company presidents” (laughs), but people rich in human experiences—a wife who has left her home, a woman who fled domestic violence, a former president who had to disappear when his company went bankrupt—are more useful than professionals as staff members.

Asano: How do you run the community financially?

Futagami: About sixty percent of our budget is provided by contributions from the guardians of the young people, and the remaining forty percent is generated by our business activities. There’s a New Start Street in a corner of Gyoutoku, at the end of which is a bakery, with a restaurant next door, then an elder daycare service, a café, a computer business, etc., so there’s a variety of businesses going on.

Asano: And the former hikikomori kids work in these businesses?

Futagami: Yeah. They’re not treated as guests, so we put them to work right away, baking bread in the bakery, taking care of the elderly, looking after kids in the daycare center.

Asano: How do the kids change during this process?

Futagami: It requires time and a variety of situations. We published a book this year called Rentaru Oneesan (Rental Big Sisters). The first step we take is to send out a “rental big sister.” I think it’s a conceit to believe you can dispatch a soulmate to someone. The most we can send is a rental big sister. They’ll spend up to a year in “slow communication,” until an opportunity presents itself and they say, “How’d you like to come visit Gyoutoku.”

Asano: All this starts with a call from the family?

Futagami: Right, most of the requests come from the parents.

Asano: What’s your batting average?

Futagami: Even if our visits are rejected at first, we meet with ninety percent of the young people within six months, and within a year seventy percent come out. Young people want friends, and they’re waiting for an invitation. We organize a trip to Tokyo Disneyland once a month, and we invite them to come along. They might have a great time with the kids from the community and decide, “Rather than going home and doing nothing, maybe I’ll give it a try,” and decide on their own to move into the community.

Asano: So it takes time, but seventy percent of these kids—whose parents were at a loss as to how to help them—end up coming out and moving into the community. I’m sure each individual and his or her circumstances are different, but how long does it take for them to become active again?

Futagami: It generally takes about six months for them to come out, and then once they’ve come to us, it averages about 15 months. It seems they grow from being around their peers and having a variety of experiences.

Asano: There are some in their 30s and 40s.

Futagami: There are. Seeing people of that age makes you aware of how much the structure for absorbing people within companies and society at large was warped by the bursting of the Bubble Economy after 1990. There are many people who were unable to find employment after high school or college. Time passed, and they found themselves in something of a stupor within a structure where it’s difficult to make a fresh start.

Asano: Do you think that society plays a larger role in the creation of these problems than the individual characteristics a person might have?

Futagami: I do think so. Also, I think young people today are more decent as human beings, in a way, than people of our generation who had such strong material and financial desires. They look at their fathers, who have worked hard, built a house, and reached economic independence, but they aren’t happy at all, and they say, “I don’t want to end up like that.”

Where they might want to choose a more human, slow way of living, the structure of society hasn’t changed at all from the impoverished value system of our generation. All they can see is the daily grind of work that brings no satisfaction. So they have no place to turn and they inevitably become social refugees. I think young people who have been raised in affluence are looking for work that helps make the world a better place and ways of working that allow them to enjoy life, rather than working long hours and earning a high salary.

The Slow Work Model

Asano: So you’re trying to develop another route, other than the standard way of working.

Futagami: That’s right. Nowadays our elder daycare service has a bad reputation in Ichikawa. From the perspective of so-called professional nursing care providers, our young people just seem to sit with the seniors, smiling and casual, and that’s not nursing care, they say. Our kids do have certification, of course. But the seniors love it, they say it allows them to relax. I think the slowness of our young people is a hidden talent, it allows us to create a “slow work” environment.

Asano: I see. The people at New Start aren’t able to be crisp and businesslike, but for seniors with cognitive disorders, for example, that may just suit them. Whereas they’re often being left behind, here there’s a comfortable rhythm.

Futagami: We also provide daycare for children, and the young people are incredibly relaxed with the children. They have, from the start, no desire to instruct (laughs). They just sort of play together, so the children are completely at ease.

Asano: But it must be a long road to get that far. Isn’t it very difficult for these kids to get to the stage where they can work in a daycare center? Even if all they’re doing is being there, it must take a long time.

Futagami: If they do just one job, they get stuck, so we tell them to do at least three jobs every week. Say, one day they’ll work at the daycare center, one day on the farm, one day caring for the seniors, and the other two days in the bakery. That way, they know it’s just for a day, so they manage to go to work. And the children and seniors, in turn, feel free to make demands of the kids.

At first, some of the young people will go to the daycare center and try to get away from the children. But to a two-year old, they figure if they can catch this young person who’s trying to escape, they’ll have a play partner all to themselves, so the children chase them down (laughs).

Asano: Because they’re children, they show no mercy.

Futagami: Then, in about two weeks, that kid who was unable to open up to anybody is sitting with the child who chased him down, smiling and feeding him his lunch. In that sense, children and seniors overcome naturally those things we consider difficulties in our work.

Asano: The way things are set up, the New Start kids get paid for the work they do there, but in fact it’s the two-year olds that should be paid (laughs).

Futagami: Exactly. There are some days when our seniors are not feeling well and their families will urge them to skip the daycare, but they’ll say, “No, I have to go and help lift those kids’ spirits. If I died there, I’d die happy.” The feeling of wanting to be of use to someone is very strong among older people, I think.

Asano: The seventy or so kids at New Start are being helped, albeit gradually, but there are tens of thousands of such young people throughout Japan.

Futagami: That’s why I tell the young people, “What we’re doing here is not just for you. We’re creating a model here that we’ll take out and promote within society as a whole.” We can help several hundred people get healthy here, but the problem is much larger than that. The kind of integrated welfare community we’re building at Gyoutoku is something we’d like to establish throughout Japan, throughout the world.

In the countryside, there can be agriculture-education-welfare triangular cooperatives like the Bulichella farm in Italy, and in urban environments, there can be a network of diverse integrated welfare communities that are dispersed throughout the city. We plan to build that network by linking up with a variety of nonprofits and social welfare providers. Having tried various approaches, I’ve come to the conclusion that young people can get their strength back and grow, not in specialized youth facilities but in this kind of integrated community, where kids can have diverse experiences with a diversity of generations.

Setting Sights on the Idea of Integration

Futagami: When you were governor of Miyagi Prefecture, you made a decision to phase out an institution for the mentally disabled and integrate the residents into the community. To me, it seems misguided to automatically assume a division of labor and entrust problems like the NEET youths and the mentally disabled to professionals. Rather these are problems for society at large and they will never be solved unless we all think about what we each can do.

In Italy, they decided to close their psychiatric hospitals and eliminate all special schools. There’s a range of opinion as to whether this was a good policy to adopt, but why were they able to do it? My interpretation is that in Italy, people believe that, except for God, we are all disabled.

So what we tell our kids is, “All people are imperfect. Just keep that one idea in mind.” Children with a variety of disabilities come to New Start, but our young people treat them all as human beings. The same with seniors and children. Mentally disabled children have come to our center, and I’ve been told that within six months they have grown so much as to be almost unrecognizable.

Asano: One thing I’d like to add to what you’ve just said is the importance of what I call “the latent power of local society.” A key distinction you’ve been making is between professionals and amateurs, and within a local society there are amateurs that play a wide variety of roles. The roles played by the seniors and the daycare children in your community are examples. Within a mix of such people, those who are considered problems are often strengthened very effectively. These amateurs may appear to be doing nothing in particular, but in fact it’s a setup in which they are exercising a great deal of consideration. This is where the mistake of placing people in institutions where they are the work of professionals becomes most evident, I think.

I’m actually working on developing integrated education, but educational specialists, including the Ministry of Education, insist that specialized schools for the disabled are much better. In these schools professionals provide them with an education that is closely tailored to their individual disabilities. If you put these children in a regular classroom, they say, the teachers become flustered and the children will be bullied.

Futagami: If you bring a group of blind children together, they aren’t able to help each other. But if you have a blind child and a child who cannot walk, they’ll immediately help each other, right? This is very important. From the teachers’ perspective, it’s easier to have a group that only includes blind children, but this eliminates many opportunities to learn. That’s why we call the thinking behind our efforts “integration.” With this idea of integration, we aim to break through the problems of sectionalized institutions where people, divided by their disability and their age, are unable to support each other, and also address the problem of the professional division between those who provide services and those who receive them. We aim to change the bottled-up condition of the hikikomori archipelago, Japan.

In your book, you use the expression, “to set sights on the island in the distance.” Your decision to phase out the institution for the mentally disabled is an example of this. It was a courageous decision. The closing of the psychiatric hospitals in Italy is another example of setting sights on the island. Thirty-five years have passed and numerous problems have emerged. For example, over the border in France, the psychiatric hospitals are filled with Italians. Even so, the Italians are sticking with their position. I think ours is a time when we need that kind of courage and determination to set a new course.

Asano: This is what I was thinking when I drew that analogy to a distant island. We can see the outline of the island in the distance, but the sea lies between here and there. The sea will turn rough, and there are shoals where we might run aground. It’s not a simple matter. But if we don’t aim the bow in that direction, we’ll never arrive. It may take a hundred years to reach the island, but if we don’t fix our sight on it, we won’t get there even in several hundred years. In other words, it’s essential to point toward the distant island in the first place.

Futagami: The challenge for us is to find a way to enjoy that process that doesn’t always go smoothly. In the words of the sociologist Ohsawa Masachi, who came to interview us the other day, I think what is required of people today is “determination and imagination.” I often encourage my staff to “Hold to your high aspirations and stir up the morass of the reality before your eyes. Don’t be a civilized NPO staffer, be an NPO primitive.”

And, more than criticizing the government administration, what is needed are concepts that will assist the government, and the idea of the integrated welfare community is one of those. What is needed is a spirit that says, “Let’s all become a little poorer and enjoy the slow life.” With the Miyakawas in Italy, we often argued intensely when there was a problem, but in the end we would smile and say, “Enjoy the process.”

Collaborating with Korea, Creating a Global Home

Asano: Well, I think we’ve gotten a sense of how Futagami, the erstwhile middle-aged NEET delinquent (laughs), became a bona fide human who is trying to accomplish something, but could you tell us what new projects you have in mind?

Futagami: There is a center for school refusers in Seoul called the Haja Center (also known as the Seoul Youth Factory for Alternative Culture). Cho Hae-joang, the founder of the center, visited us at Gyoutoku last spring, and we found that we shared many common ideas. We had run a café called Engawa in Incheon in South Korea, which the landlord had decided to close, but we still had all of the furnishings and equipment. Hae-joang suggested we reopen Engawa at the Haja Center. The idea is provide a place for school refusers to gather, where they can explore Japanese animation and such. As part of this effort, twelve female university students from Korea are now at New Start for a three-month stay.

Asano: They’re here for training?

Futagami: They’ll stay at our dormitory for three months and work together with the young people. We provide their room and board. For the Korean kids, they get to experience life in Japan for three months for free. And having them around provides a stimulus for the hikikomori kids. We’ve been set up to take in foreigners in the past as well, but now plans are moving ahead for us to go abroad and set up a café in the center of Seoul. I’ll also be participating in an international symposium in Seoul this fall on new approaches to education in the 21st century. So I’m looking forward to doing something different, something new in the country of my birth.

Asano: The Korean students who come to your center are essentially here to have a good time, but then, in a natural way, they end up invigorating the ex-hikikomori kids. This seems true of all of your activities. The participation of nonspecialists ends up making a contribution to society. This kind of scheme, it seems to me, will be increasingly important to the future of Japanese society.

Futagami: We are establishing bases in Rome and Manila, at the same time we are integrating Americans and Italians, foreigners who are studying Japanese, into our activities in Gyoutoku. Their imperfect Japanese provides something of an opening to the Japanese kids who have trouble communicating. Interpreting their slightly skewed Japanese seems to provide an opportunity. Foreigners are also very effective in the “rent a sister” program. Where conversation among Japanese doesn’t result in communication, seeing an Italian woman trying to speak and gesturing emphatically, a boy who never laughed will suddenly break into a smile.

Japanese believe we can understand each other through language, so we end up depending on language too much. The two hours I spent in silence, working with my principal planting trees when I was 17, amounted to a very dense communication that still provides food for thought forty years later. Japanese have lost sight of this kind of nonverbal language, this kind of total, slow communication. I can’t help but feel that for the Japanese, language has caused a kind of autointoxication, and that communication is inadequate throughout the society.

I’d like to have about thirty foreigners in addition to the seventy Japanese kids in our dormitory, and to make it into a Global Home. I have the sense that this will create strength for the NEET and hikikomori kids to make a breakthrough. We’re an NPO that works in the spirit of Marisa’s “Just the easy kids, there’s no point!” So we’ll proceed through bold trial and error, enjoying the process as we go along.

Asano: Sounds like fun. Thank you very much.