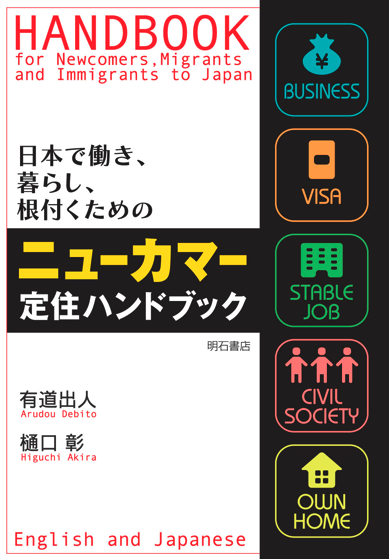

Handbook for Newcomers, Migrants, and Immigrants to Japan

Arudou Debito & Higuchi Akira

A new bilingual book by lawyer Higuchi Akira and author-activist Arudou Debito went on sale in March 2008. The book includes advice on securing stable visas, establishing businesses and secure jobs, resolving legal problems, and planning for the future from entry into Japan to death. In this extract, they explain the rationale behind the project and offer advice for how to deal with problems in Japan and integrate into Japanese society.

Migration of labor is an un-ignorable reality in this globalizing world. Japan is no exception. In recent years, Japan has had record numbers of registered foreigners, international marriages, and people receiving permanent residency. This guidebook is designed to help non-Japanese settle in Japan, and become more secure residents and contributors to Japanese society.

Japan is one of the richest societies in the world with a very high standard of living. People will want to come here and indeed are doing so. Japan wants foreigners too. Prime Ministerial cabinet reports, business federations, and the United Nations have advised more immigration to Japan to offset its aging society, low birthrate, labor shortages, and shrinking tax base.

Unfortunately, the attitude of the Japanese government towards immigration has generally been one of neglect. Newcomers are not given sufficient guidance to help them settle down in Japan as residents with stable jobs and lifestyles. HANDBOOK wishes to fill that gap. We wish to provide everyone concise advice as veterans of the system, to save readers time and trouble, and help them find out their options for living in Japan.

WHAT TO DO IF . . . RESOLVING PROBLEMS

Living in Japan (or in any country) means that problems will come up. However, Japanese society and government does not always make clear (especially to newcomers and non-native speakers) what you can do to get help. Although we cannot cover every possible scenario, here are some headers for common issues:

What if you are asked for your passport or “gaijin card” by a police officer?

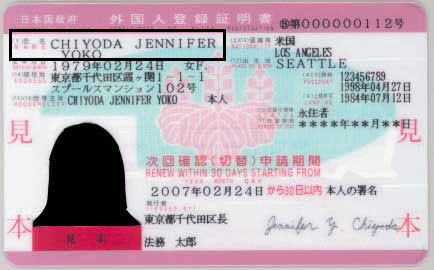

Your Alien Registration Card (ARC, informally known as the “Gaijin Card”, or gaikokujin touroku shoumeishou is the wallet-sized card you receive from the local Ward Office when you register your address in Japan. It is used in place of your passport, and issued to people who are not tourists. It is proof that your visa is legal, and it works as personal identification (ID). Anyone with a registered Japanese address (i.e. people on three-month visas and up) is no longer required to carry a passport in public. Instead, you are legally required to carry your ARC 24 hours a day, or face arrest under the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (nyuukoku kanri oyobi nanmin nintei hou).

Foreigners in Japan are likely to be stopped and asked for ID (the ARC) by police officers. Politicians have announced plans to halve illegal aliens by 2015, and restore Japan’s status as “the world’s safest country”. In 1999 the National Police Agency created an internal body (the Policy Committee On Internationalization, Kokusaika Taisaku Iinkai) to step up the policing of foreigners. June is officially designated as “Campaign Month against Illegal Foreign Workers” (fuhou shuurou gaikokujin taisaku kyanpein gekkan), with announcements issued by the Immigration Bureau. There are also “Prevention of Terrorism” and “Control of Infectious Diseases” policies in the pipeline. The crackdown will affect all foreigners (and sometimes foreign-looking citizens) in Japan, so be prepared. ARC checks can happen anywhere.

If the police officer shows his badge, you must display your ARC or face arrest under the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act. However, you do have some rights. The Foreign Registry Law (gaikokujin touroku hou, or gaitouhou for short) requires you to carry the ARC. It does NOT require you to carry your passport (again, passports are required for tourists, governed under a different law).

So if the police demand your passport, say, softly and politely, “I am not a tourist. I am a resident of Japan. I am not carrying my passport.” (Watashi wa tsuurisuto ja arimasen. Nihon no juumin desu. Pasupouto wa motte imasen.)

If the police ask for your ARC, then ask the police for some ID. Under the Foreign Registry Law, Article 13, an officer must display identification if asked for it as long as you are not near a Police Box (kouban). We recommend that you write down the policeman’s name and six-digit badge number (say: “Sorry, please show me your name and badge”, Sumimasen, onamae to keisatsu techou o misete kudasai) for future responsibility. If the policeman shows his badge, then you must show your ARC.

If the policeman refuses to show you ID, we recommend that you continue negotiations calmly, with a smile, to show that you know your rights, and that the police should know their duties. We recommend you print up the pertinent laws and carry them around with you, just in case.

Download it here:

However, do not let the situation escalate. The police in Japan are very powerful. Because you are a foreigner, falling under different laws than citizens, the Japanese police have the power to stop, search, and seize you at any time under any suspicion. (They cannot do this to citizens, under the Keisatsukan Shokumu Shikkou Hou, or the “Police Enforcement of Duties Law”, without suspicion of a specific crime or probable cause.). You do not want to get arrested in Japan

If you do not cooperate, they may want to take you to the nearest Police Box. By law they cannot do this unless they arrest you (taiho). Police may stress that questioning is “voluntary” (nin’i no torishirabe), but insist that you do not wish to be questioned without a good reason. Calmly ask questions with a smile, such as, “Am I under arrest? If not, then I am not under any obligation to go to the Police Box.” (Sumimasen, watashi wa taiho sarete imasu ka. Sou ja nakereba, kouban made iku gimu wa nai to omoimasu.)

Those are your options. Be careful. Don’t get angry, raise your voice, or make any sudden moves with your body. If the Japanese police perceive you as threatening or suspicious, you may be taken into custody, for koumu’in shikkou bougai, or the “obstruction of a public official in the course of his duties”.

What if you are asked for your passport and/or gaijin card by anyone else?

By law, only those who have policing powers granted to them by the Ministry of Justice (police officers, Immigration officials, etc.) may ask for the Alien Registration Card (ARC).

â— Download the laws governing the ARC in English and Japanese here.

However, with government policy pushes against terrorism and illegal aliens, Japan’s police are asking the general public to help them find “bad foreigners” (furyou gaikokujin). As a result, we have received reports of hotels, video stores, sports clubs, and employers asking to see and photocopy ARCs, sometimes as a condition for providing service or continuing employment. This is not legal, and you are under no obligation to cooperate.

Hotels may insist that they must ask you for your passport or ARC because laws governing hotels have changed (as of April 1, 2005). We suggest you inform the management that the law change only requires tourists to show ID; residents of Japan are still not required to show ID, so say that you are a registered resident of Japan. If you need a copy of the pertinent laws in English and Japanese, provided to hotels by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, download them from

â— here.

However, many stores will require ID from every customer (regardless of nationality) before allowing access to their facilities (such as renting equipment). If you do not want to show your ARC, we recommend you ask the management if you may show the same ID as a Japanese customer, such as a driver license (unten menkyo shou é‹è»¢å…許証) or a health insurance policy (kenkou hokenshou å¥åº·ä¿é™ºè¨¼), which works for Japanese who do not drive. (There is, by the way, no universal ID card system in Japan.)

But if a store clerk insists that all foreigners must show the ARC as ID, we recommend a) that you inform them that this is not required by law (download copies of the law from the link above and show them as proof), b) that you show your ARC, or c) that you take your business elsewhere. That is all you can do.

Of course, if you have no other form of ID, and do not mind showing the clerk your ARC, go ahead. But we believe you should not need to show any more ID than what is legally required from a Japanese citizen, except when it is a situation specifically involving the policing of foreign residents. Renting a DVD at a video store should not require proof of a valid Immigration visa.

However, if your employer is requesting proof of a valid visa (because the police are also contacting businesses to find illegal aliens), we suggest you cooperate. We believe that employers should (finally) be held responsible for employing their workers legally in Japan, and that employees should cooperate.

As of October 1, 2007, the law requires employers to confirm their non-Japanese employees’ visa status, and register their foreign employees with Hello Work. People employing visa overstayers, or non-Japanese with incorrect SOR, will be fined up to 3,000,000 yen. However, the law only requires that you display, not photocopy, your ARC, and your passport is not required. Also, you need not display your ARC every time you receive money. If anyone but your main employer asks for your ARC, tell them that you are not required to do so by law.

What if you are arrested or taken into custody by the Japanese police?

Being arrested (taiho 逮æ•) or taken in to custody (kousoku 拘æŸ) by the Japanese police is one of the most frightening experiences you can have in Japan. Avoid it.

If you are in custody without arrest, Japanese police can hold you for voluntary questioning (nin’i torishirabe¹) indefinitely. You are not allowed to have a lawyer during any police interrogations (tori shirabe, jinmon) in Japan, so be careful what you say. Try to find out why they are holding you, and if you not under arrest, ask if you may leave. If you try to get up and leave prematurely, they will just formally arrest you for the crime of koumu’in shikkou bougai (“obstruction of a public official in the course of his duties”³). Time it right.

To confirm whether or not you have been arrested, ask “Watashi wa taiho sarete imasu ka.” Then ask on what charge (donna yougi de taiho sarete imasu ka).

However, we recommend that you do not speak in Japanese during interrogation. You should communicate with police in your native language. Ask for an interpreter. Do not talk until an interpreter arrives, because if the police feel that your Japanese ability is sufficient, they will treat you like any other Japanese suspect. There have been cases of suspects claiming that they confessed to crimes without their full understanding.

If you are placed under arrest, Japanese police can hold you in custody for up to 23 days (3 days of initial interrogation, extendable by 10 days a maximum of two times if a judge approves (which often happens, unless a lawyer intervenes). In rare cases, they can get a five-day extension on top of that. They can also re-arrest you on a different charge and start the process all over again. However, you will be allowed to communicate with the outside world on your third day of arrest. Use this time to contact your embassy, to get you a lawyer and contact your family.

Interrogations, like interrogations in many other countries, can involve teams of police, under hot lights and in smoke-filled rooms, asking you similar questions again and again for days. Repeated questions is an interrogation technique: They are trying to detect differences in your responses to find something suspicious. They often say they will release you as soon as you sign a confession (kyoujutsu chousho), but if you are innocent, DO NOT SIGN. Convictions after confession are very common in Japan, you will probably face punishment, meaning losing your job, being fined, even going to jail.

The Japanese police interrogation system has many problems. There are credible reports of extracting information through unfair means (such as signed confessions in a language that detainees could not read), through physical and mental duress (beatings, sleep deprivation), and denial of outside communication, consular contact, or legal counsel. There have been deaths in custody. More on this at the United States Department of State Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, updated annually:

Find it here.

Japanese criminal law tends towards the Napoleonic (i.e. a suspect is presumed guilty, and must prove his innocence), with a heavy reliance on confession. Moreover, the right to remain silent (mokuhi ken), although guaranteed in the Japanese Constitution, is not a good defense, because it will arouse more suspicion. So answer questions, be cooperative, calm, and friendly, but DO NOT SIGN ANYTHING WITHOUT ADVICE FROM A LAWYER!

We repeat: DO NOT SIGN ANY CONFESSION. Or you will go to jail. Confession (jihaku 自白) equals conviction in Japan. It will not be overturned later in court.

Information on how to get a lawyer (ask for the Lawyer on Duty, or touban bengoshi 当番å¼è·å£«) from the Japan Bar Association (Nichibenren, in English):

Final word: The Japanese criminal justice system, with conviction rates at nearly 100%, overwhelmingly favors the prosecution. Do not get arrested in Japan.

GIVING SOMETHING BACK: DEVELOPING JAPAN’S CIVIL SOCIETY TO HELP MULTICULTURALISM IN JAPAN

Now that you have firmly established yourself in Japanese society and made plans to live here long-term, we suggest you remember how you felt when you first arrived here. Sometimes you probably felt lost, and wished somebody was there to help you, right?

We believe you should help others who follow in your footsteps, and make it easier for newcomers to fit into Japan. This means getting involved and giving something back to society. By helping others, you will eventually be helped too, because the standard of living will rise for everyone. A rising tide lifts all boats in the harbor.

This is why we suggest you do what you can to strengthen Japan’s Civil Society. By “Civil Society”, we mean not-for-profit organized groups, clubs, volunteers, and associations generally operating independently of the government, put together by people at the grassroots level, hoping to make the world a better place. Examples of groups in any Civil Society can include universities, NGOs, environmental movements, religious organizations, minority associations, organized local communities, unions, consumer advocacy groups, human-rights watchdog organizations…

Non-Japanese residents, particularly newcomers, may feel pressure to live “completely Japanese-style” (especially if you are in the Japanese countryside). We believe this is because many of the people around you will think that Japan is unique, “foreign” means “different from Japanese”, and assimilating means giving up your differences to do everything the “Japanese Way”.

However, we a) do not believe there is one unified “Japanese Way” to do anything, and b) do not believe you should feel pressure to conform your private life to things you are not culturally or psychologically comfortable doing.

We of course recommend you keep a healthy curiosity about, and the proper respect for, the society you are now a resident of. However, just because you live in Japan does not mean that you must sacrifice all of your home culture, attitudes, and beliefs. It is possible to live in Japan both as a Japanese and as a product of an overseas culture. Not half, but double. And it helps if you do not do it alone. This is why you need a group.

What group you should join depends on your needs. However, if you wish to stay in Japan long-term, we recommend that you find like-minded people to spend time productively with. Find other people who understand your attitudes and beliefs, who can support you when you feel lost or lonely. If you do not, you may feel isolated, alone like many newcomers who do not fully assimilate. Isolation will very often contribute to mental stress and an unsustainable lifestyle.

There are many of these types of groups in Japan, believe it or not, and the number is growing every year as more people learn about volunteerism. You might not hear about them in the media, but they exist. You have to find them.

1 How to find a group

You can of course visit your local government, tell them your needs, and ask what groups are out there.

Please understand, however, that many groups that advertise themselves as promoting “internationalization”, especially those run by local governments, are often in our experience not very “international”. Many are social clubs set up by retirees and hobbyists. In our experience, these groups are often trying to “help Japanese get used to foreigners”, not help foreigners get used to life in Japan.

Fortunately, the Internet has made things easier for non-Japanese in Japan. From the mid-1990’s, foreigners have been able to chat, mail, and connect with each other as never before, regardless of where they lived. We recommend you invest in an Internet connection at home. If you have a phone line, then save your money, buy a computer, and get hooked up. The Internet is not all that expensive to use anymore, and we are quite sure it will be worth your money.

Once on the World Wide Web, do searches in your native language if necessary (try www.google.com), and see who is out there in a similar situation. Most organizations that are worth joining have a web site to explain who they are and what they do. Even if you do not find a group, you may find some likeminded people to chat with, maybe even advise you.

The point is we wish to stress once again: Unless you have the mental training of a hermit or an ascetic, we recommend you find friends or people to communicate with. Do not make your life in Japan into a solitary confinement experience.

2 Starting your own group

Why might you start your own group? Because people’s needs change over time. The interests or problems which a group was designed to address yesterday might not address new interests or problems today.

In our experience of starting our own groups, you just build it and people will come. Most of the established mailing lists, for example yahoogroups.com, offer a place for you to create a group, write your group’s goals on a website, and make it searchable. This costs nothing and it is easy to maintain. You can also establish your own webpage and “blog” (Internet diary/bulletin board) to explain your goals, and the search engines will eventually find you. It is the cheapest, easiest way to get yourself out there.

An example of a grassroots Internet group (which readers can join) is here.

Do not expect dozens of people to find you and join your group immediately. Building a group may take years, and you may have people joining who do not share your goals (the Internet is full of people, nicknamed “trolls”, who viciously criticize people anonymously for sport). We suggest you be tough, and choose members who believe in your group’s goals and intentions. People who are not constructive on the list will waste everyone’s time.

We also suggest face-to-face meetings for drinks or coffee from time to time; in our experience the Internet is not a complete substitute for interpersonal conversation. If you want to forge trustworthy and reliable alliances, even possibly friendships, get to know your members as people, not just as opinions.

3 Formalizing your group

If you want to be taken more seriously in public, consider registering your group with the government. If you find that idea frightening, or you do not have the time or the resources, then start small:

Unregistered organizations (voluntary organizations nin’i dantai)

Under this title, you can remain a voluntary organization without a lot of paperwork. Save your energy and money until your activity draws enough attention and people. Raise enough capital and human resources and then set up a legal entity.

The drawback of being as an unregistered organization is that you have little credibility. You cannot make a contract or legal documents, open a bank account or rent property under the name of your organization, or create a trustworthy balance sheet. You can, however, open a bank account (in your name, but under a title that you create even if you have not registered it with the authorities). But who would contribute to your fund except people who know you and your group personally?

So if you want your group to grow and become more influential, register.

Registered Organizations

If people in your group know how to run a business, and can manage an office and keep accounts, you can register your organization with the Japanese government as a Non-Profit Organization (NPO) or a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO). You will not be alone. Since the government formalized rules in 1998, these groups now number in the tens of thousands in Japan.

The advantages of formally registering are that you can become a legal body (see Chapter 3), rent an office, and open bank accounts in the name of your group. You will be able to receive charitable contributions from individuals and corporations (which may be tax-deductible for them), even the United Nations and the Japanese government. And you will also be taken more seriously by the mass media and other groups when networking and publicizing your issues.

The disadvantage is that the Japanese government will check into the contents of your organization, and decide whether to give you permission to contribute to society. If administrators see you as primarily engaged in religious or political activities, or putting “unfair” restrictions on membership, your application will probably be rejected. In addition, of course, you will have to draw up a constitution and a clear statement of purpose in Japanese.

MAKING ACTIVISM MORE THAN A HOBBY

Regardless of whether you actually make an organization, do you feel so strongly about something that you could devote a substantial amount of your time and energies towards it? We encourage you to do so. That will of course involve awareness raising and public appeals. How to do that:

a) Websites, “blogs”, and “wikis”: There are several ways of organizing information so that it is archived and accessible 24 hours a day. If you have an issue you can summarize on one Internet page with short, clear points, do so. This will save you time and energy. This way you can direct reporters and concerned readers to a website and not have to repeat yourself constantly.

â— Examples are here , here, here, and here.

b) Mailing lists: These are collections of email addresses so that you can contact people directly with updates and articles. If you are dealing with a long-term issue, you can send periodical emails to supporters, reporters, and interested people. This has its advantages, because just waiting for people to come to your website is not always as effective. Direct mails keep the news fresh and the reporters alert. You also show people that you are serious about keeping the issue alive, following up on this problem until it gets solved.

c) Speeches: One positive thing about Japan is that people in general will calmly listen to your viewpoint (especially if you are “from a foreign culture”) even if they do not agree with what you say. As long as you do not have the reputation for being a “radical” or a quick-tempered person, you may get invitations to speak. After you understand your audience and its intentions, gratefully accept these invitations as an opportunity to talk about the issue and to rehearse your arguments. Welcome counterarguments–they will help you sharpen your future arguments.

Also, remember that in terms of speaking tone, acting sunny with humor is almost always better than speaking in an angry or sad voice. Make a good impression of yourself as a person even if you have to sing a sad song. Try your best to give your speech in Japanese.

d) Press conferences (kisha kaiken): Anyone can hold a press conference. It is not difficult. For example, let’s say you wish to talk about something involving City Hall. Call up the City Hall Press Club (kisha kurabu è) and tell them that you will speak on a certain topic at a certain time and a certain place. We recommend you fax them a one-page brief (in Japanese is best) with the issue, time and place, and informational websites. They will put the fax in every newspaper mailbox at the Press Club. You can also ask if you can speak at the Press Club itself, although if they say yes, you generally will get no more than a sofa and a coffee table as speaking space. If that is not satisfactory, you can also speak at local citizen centers and public forum centers, but these events will cost you money, and staff at these centers may refuse to rent a room to you if they feel your issue is too political or business-oriented.

The best time to start a press conference is around 11AM (reporters generally come to work at 10AM, and this will catch them before lunch), or between 1 and 2PM. Articles done at this time will probably end up in the evening edition (yuukan), which has a smaller audience. If you want to make the morning edition (choukan), start your press conference at around 3PM.

Be prepared. Always have handouts and business cards to give reporters. Make sure that everything you want to say is written down, or they may misquote you. We suggest that you speak for no more than 15 minutes, then open the floor to questions. Plan to be finished within an hour. Remember that reporters are people too. They have angles, deadlines, and boredom levels, so keep it quick and interesting, if not even a little entertaining. If they are interested in the issue, they will give you more press coverage in future.

Get business cards (meishi) from all journalists who attend. Ask them at the beginning of the press conference to leave their cards in an assigned spot. You will get them–journalists are ethically obligated to identify themselves when asked. This way you will know who attended, what media to check for the articles, and what reporters’ email addresses to add to your mailing lists. When you find the articles, clip them for photocopying (pointing to newspaper articles really increases your credibility). We recommend you scan then and put them on your webpage, or download them from their site as text (do this quickly, as many Japanese news sites remove their articles within days). This will not cause copyright problems. Under the Fair Use Doctrine, as long as you a) acknowledge the source (you do not claim the writing is yours), and b) do not charge money for downloading the articles from your site, you can use these articles for educational purposes.

And of course, if you give a press conference and nobody comes, do not be disappointed. At least you tried. Try again later when you think the Japanese media will find a “peg” (a current newsworthy topic of interest) to hang your story on. For more information, and a case study of how a news story was made into an international issue, see the book “JAPANESE ONLY: The Otaru Hot Springs Case and Racial Discrimination in Japan.”

e) Forums: These are difficult, taking weeks or months to organize, a sizeable investment of money in advertising, and people skills to inspire other people to cooperate. We suggest you get involved with some other groups who have done forums, and learn from their experience first.

f) Outdoor demonstrations: Signatures on petitions and demonstrations are possible, but in Japan some limitations apply. If you want to do anything outside a room of a political nature (in other words, in public without walls surrounding your message), you will have to get the permission of the police, as well as any storefronts/business organizations in the area of your demonstration.

More on outdoor demonstrations here.

More on street petitioning in Japan here.

Foreign workers protest working conditions at Nova Schools in 2007

g) Meeting politicians and bureaucrats: If your issue involves creating and/or interpreting the laws or ministerial directives, make an appointment with the pertinent ministry or local government office. Give your arguments in writing, with a brief oral introduction, and ask for a reply in writing. You probably will not get much of a response from them, but if you do, it will be an official statement to point to in future, to show that the government is aware of the issue. It will also be proof that you tried all channels. Again, more in book “JAPANESE ONLY: The Otaru Hot Springs Case and Racial Discrimination in Japan.”

Running for Elected office

You may also have the dream of changing Japan by becoming a politician, and putting your energy into policies. This is not impossible. Japan is a democracy, and has elected representatives to its Diet (parliament). Some representatives are foreign-born or with foreign roots (such as ethnic Taiwanese Ms. Ren Hou, ethnic Finn Tsurunen Marutei, and the late Arai Shoukei, an ethnic Korean), so “foreigners” do get elected.

However, to vote or run for office, you must have Japanese citizenship. Proposals to give long-term foreigners, even the Japan-born ethnic “Zainichi” Koreans, Chinese, etc., the right to vote and hold office have generally been unsuccessful.

If you have political ambitions, we suggest you start small. Understand how the Japanese political process works by volunteering for an elected representative’s office at the local, prefectural, or national level. Local politicians surprisingly often like the cachet of having a foreigner on staff, sometimes making them visible during election campaigns. Even when an election is not taking place, some national Dietmember offices advertise unpaid internships, so look around. Citizenship is not required.

For some stories from one of the authors on how election campaigns are run at the local level, see here.

Even if you do not wish to get involved in elections or staff volunteers, you can still lobby politicians. Make an appointment at their office, and you might get an audience. Do not get your hopes up unless your timing is good or the issue you want to lobby about is current. It helps to have the mass media behind you, so review the section above on press conferences etc. beforehand.

STAYING POSITIVE WHEN PEOPLE SAY “JAPAN WILL NEVER CHANGE”

Our experience is that you will hear this sort of thing from all sides, Japanese and non-Japanese. Japan is unique, Japan is special, Japan is different, Japan will never change… et cetera. We do not believe this. No society is completely closed to outside contact, opinions and influences, especially in this age of increased international communication, cooperation, and globalization.

We also do not believe that any society is so perfect that it cannot be improved in some way. Instead, we think that anyone regardless of nationality has the right, if not the obligation, to speak up and be a contributing member of society. And if anyone says that, “you should not force your foreign ideas on the Japanese”, just remember: an idea has no “nationality”. It is either a persuasive idea, or it is not. If your idea is portrayed with adequate knowledge and proper respect of Japanese customs and manners, you may in fact convince enough people to change things. . . .

Speaking out is not something that many people will feel comfortable doing, including yourself. However, if enough people get together as a group to show society that a problem needs addressing, it may indeed happen, as even Japanese history demonstrates.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO TO CREATE STRONGER ROOTS IN JAPANESE SOCIETY

We can summarize the basics of what everyone needs in order to live a more stable, secure life in Japan:

Aim for Permanent Residency (eijuuken). You will need a few years and a stable job before you can qualify for this, but all the benefits are there.

Aim for a full-time job without a signed, time-limited or term-limited contract. Make sure it has health insurance, employment insurance, retirement pension, and a bonus. This is what most Japanese workers have. So should you.

We also recommend that you join a labor union, since experience shows that especially as a non-Japanese resident, few labor laws will be guaranteed in a dispute unless you have labor representation.

If you have enough business skills to become self-employed, consider founding your own business.

3] Inkan stamp, bank account, driver license, insurance, credit card, investments for the future, and Japanese language ability.

4) We recommend people volunteer their time to join groups or form their own group. Not only will you help other people who come after you to assimilate into Japanese society, you will also find other people with whom to share your experiences. This will help you feel less isolated, and make your life here more meaningful. These are the very basic things you need to live in Japan securely. Everything else depends on your personal situation, and good luck.

Finally, remember that this book is designed to help people who are here legally. For better assimilation, we recommend that you obey Japanese laws

Arudou Debito is an activist, writer, blogger (www.debito.org), and columnist for the Japan Times. Higuchi Akira is an administrative solicitor in Sapporo who also is qualified as an immigration lawyer by Sapporo Immigration. Find more details on the book here.

For Paypal orders of the book click here.

Posted at Japan Focus on March 23, 2008.