The Peace Deal Obama Should Make: Toward a U.S.-North Korea Peace Treaty

With Middle East and South Asia negotiations going nowhere, the United States should seize the chance to make a historic agreement with North Korea.

Anthony DiFilippo

In what Pyongyang’s state media billed as a “military drill,” North Korea on January 28, 2010 fired artillery shells near its disputed border with South Korea. South Korea responded by firing its Vulcan cannons into the air – a sign, according to the South Korean press, that Seoul would not give in to intimidation. The incident made global headlines, even though these skirmishes near the Northern Limit Line dividing the countries in the Yellow Sea, which North Korea does not recognize as a legitimate border, have been ongoing for years. If U.S. President Barack Obama wants to resolve once and for all the situation on the Korean Peninsula, he’s going to have to take an innovative approach to solving the underlying problem: pushing at last for a formal end to the Korean War.

Map shows division of Korea at 1953 armistice that remains in effect today

North Korea has made its position clear: It wants a treaty to supplant the nearly 57-year-old armistice agreement that ended the war. North Korean officials, of course, have floated the idea before, only to be turned down flat by previous U.S. administrations. But no moment has ever been so auspicious for a treaty that is in the interest of both countries and the peace and security of Northeast Asia.

The “Permanent” Armistice Agreement

The armistice agreement ending the fighting in the Korean War that began in June 1950 was signed on July 27, 1953 by the United States, representing the United Nations forces, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), which also acted for China; it became effective on the same day. Like any other armistice, it was meant to be a temporary agreement that stopped the hostilities until a permanent peace could be established. However, it has become a permanent armistice agreement governing a situation of mutual hostility more than half a century later.

Panmunjom, Korea, July 27, 1953. An armistice is signed by U.S. Army Lt. Gen. William K. Harrison, Jr. (left), senior delegate, on behalf of the UN Command Delegation, and General Nam Il of the DPRK, senior delegate, Delegation of the Korean People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteers. The armistice was reached after 158 meetings spread over more than two years.

Article IV, paragraph 60 of the armistice agreement specified that the two sides recommend to their governments that “within three (3) months after the Armistice Agreement is signed and becomes effective, a political conference of a higher level of both sides be held by representatives appointed respectively to settle through negotiation the questions of the withdrawal of all foreign forces from Korea, the peaceful settlement of the Korean question.”1 Not only was this conference delayed by several months from the time designated in the armistice agreement, but ongoing problems stemming from the Cold War, also made the issue of the removal of U.S. troops from South Korea a major stumbling block in subsequent peace talks.

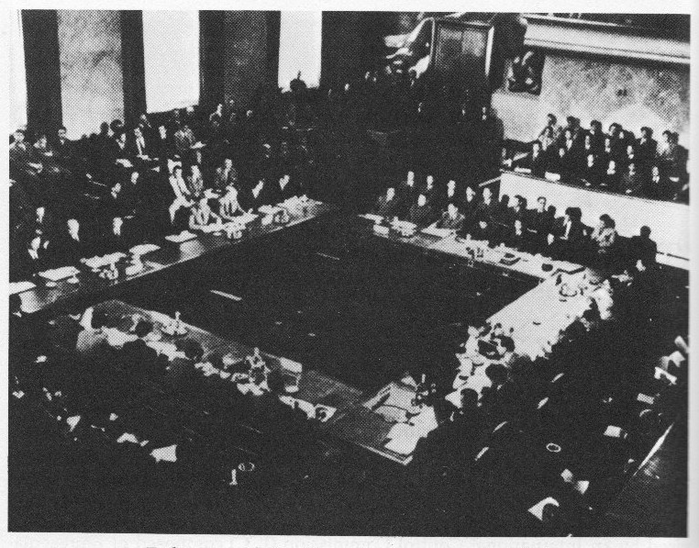

The initial discussions on a peace treaty to end the Korean War occurred at the Geneva Conference on Korea and Indochina, which took place from April to June 1954. For nearly two months, representatives from 16 allied countries, including the United States and South Korea, faced off with their counterparts from the DPRK, China and the Soviet Union. Despite having held 14 plenary sessions, the Geneva Conference came nowhere close to reaching an agreement on a peace treaty. The political bifurcation created by the animosity evident in the early Cold War years left the two sides as far apart at the end of the Geneva Conference as they were at the beginning.2

The Geneva Conference on Korea and Indochina

Perpetual tensions kept the realization of a peace treaty to end the Korean War completely out of reach throughout the Cold War. Even when the Cold War ended in the early 1990s, it did not end in Northeast Asia, above all with respect to Korea. With tensions still running high there, the prospects for a peace treaty were kept at bay. Cold War politics have remained evident in U.S.-DPRK relations to this day.

The first North Korean nuclear crisis emerged in the early 1990s and ended in October 1994 when Washington and Pyongyang signed the Agreed Framework, which effectively froze the DPRK’s plutonium-reprocessing facilities, mainly located at Yongbyon. Deep tensions between Washington and Pyongyang, however, remained after the signing of the Agreed Framework.

In April 1996, when President Bill Clinton met with South Korean President Kim Young Sam in South Korea, they advanced the idea of discussions on a peace treaty. At the end of June 1997, the DPRK agreed to participate in four-party talks among the United States, North and South Korea, and China.3

Four-party talks took place between 1997 and 1999; however, no agreement was reached on a treaty. Significantly, Washington and Pyongyang had opposite views on the issue of the presence of U.S. troops in South Korea. Although there have been a very small number of exceptions,4 Pyongyang has regularly and vehemently opposed the presence of U.S. troops in South Korea, as it did during the time of the four-party talks. Moreover, during the four-party talks, Pyongyang did not want South Korea to be a signatory to a peace treaty. In the end, the four-party talks literally faded away with no progress being made toward a peace treaty. Certainly not contributing to an auspicious climate for the four-party talks was the fact that by late 1998 Pyongyang began complaining of the fact that “the DPRK has faithfully implemented its obligations for nuclear freeze under the DPRK-U.S. agreed framework, whereas none of U.S. obligations has been smoothly carried out.”5 This, of course, was not troubling to the Republican-controlled Congress, many of whom were strongly opposed to the Agreed Framework worked out by the Clinton administration.

The end of the Clinton administration brought some improvement in the relationship between Washington and Pyongyang. In early October 2000, Washington and Pyongyang signed a joint statement on international terrorism. This joint statement expressed Washington and Pyongyang’s shared view that international terrorism endangers world peace and security.6 Less than a week later, Washington and Pyongyang signed a joint communiqué that indicated their agreement “to work to remove mistrust, build mutual confidence, and maintain an atmosphere in which they can deal constructively with issues of central concern.” Although the four-party talks by this time were no longer ongoing, in this joint communiqué Washington and Pyongyang indicated that they wanted “to reduce tension on the Korean Peninsula and formally end the Korean War by replacing the 1953 Armistice Agreement with permanent peace arrangements.” The joint communiqué concluded by stating that Secretary of State Madeleine Albright would soon be visiting the DPRK, which she did later that month.7 Although it never happened, there was even some discussion that President Clinton might visit the DPRK before he left office.

However, the Bush team quickly turned things around – and not for the better, labeling Pyongyang as part of an “Axis of Evil.” Pyongyang soon began regularly complaining about Washington’s hostility toward the DPRK, particularly following the Bush administration’s Nuclear Posture Review in which the United States threatened to use nuclear weapons on North Korea. Recognizing that a peace treaty was not in the cards, in late October 2002, immediately after the onset of the second North Korean nuclear crisis, Pyongyang began calling for a nonaggression treaty between the United States and the DPRK.8 Meanwhile, however, Tokyo’s continuing emphasis on the abduction issue (the kidnapping of Japanese nationals by DPRK agents during the 1970s and 1980s) contributed to the U.S. State Department designation of North Korea as a state sponsor of terrorism, resulting in worsening relations between Washington and Pyongyang. In these circumstances, hopes for any kind of treaty approached zero. Even though the joint statements that came out of both the September 2005 and September 2007 six-party talks addressed the issues of making progress in normalizing relations between the United States and the DPRK and between the latter and Japan, this never happened.

Why a Peace Treaty Now Makes Sense

Signing a peace treaty now, politically difficult as it could be for Obama, is the best way to end the standoff in Northeast Asia and resolve the North Korean nuclear issue for good. But on what terms? A peace treaty with North Korea would need to be based on a quid pro quo: North Korea’s denuclearization in exchange for the accord. The United States, North and South Korea, and China – the countries that were the principal combatants in the Korean War – would sign the treaty immediately, but it would not enter into effect until Pyongyang denuclearized within a reasonable time, say, 12 months. Barring unforeseen circumstances, if Pyongyang failed to denuclearize, the treaty would become void. Moreover, Pyongyang will need to abandon its past aversion to having Seoul sign a peace treaty. Today, South Korea clearly has a vested interest in seeing the DPRK eliminate its nuclear weapons and stop the work that enables it to produce them, since both preclude the unification of the peninsula, violate the 1992 Joint Declaration of the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula signed by the two Koreas, and increase the risk of war on the peninsula.

While the DPRK would be required to denuclearize by the end of the prearranged time, the terms of the agreement reached during the February 2007 six-party talks among the United States, the two Koreas, China, Japan and Russia would need to be honored as well. These talks produced agreement to provide the DPRK with “economic, energy and humanitarian assistance up to the equivalent of 1 million tons of heavy fuel oil.” With the return of inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency to the DPRK to monitor denuclearization activities, regular reports by the agency on the North’s progress in denuclearization could provide the basis for timely provision of assistance. In other words, the treaty would be predicated on step by step progress by both sides.

It is in Pyongyang’s short- and long-term interests to make certain that a conditional peace treaty becomes permanent. Of course, any treaty with leader Kim Jong Il will be a tricky feat to pull off given conservative opposition in the United States,9 as well as among some U.S. allies in Asia. Critics of the notion contend that North Korea intends to forsake neither its nuclear weapons capabilities nor its nuclear weapons, regardless of any agreements it signs. Rather, they say, Pyongyang is committed to achieving international recognition as a nuclear weapons state.

But the evidence suggests otherwise. Although the six-party nuclear talks have certainly not been problem-free, they have achieved limited successes – sometimes through bilateral discussions between Washington and Pyongyang. In the joint statement that came out of the September 2005 six-party talks, Pyongyang committed North Korea to denuclearization. Besides disabling a sizable amount of its nuclear weapons capabilities, Pyongyang submitted its nuclear declaration, as required, to Beijing in June 2008 and shortly thereafter blew up its cooling tower at its Yongbyon nuclear facility. By July 2008, Pyongyang had disabled about 80 percent of North Korea’s nuclear weapons capabilities at Yongbyon, though this progress was subsequently reversed following a verification dispute with Washington.

North Korea disables the nuclear reactor at Yongbyon (link)

Still, North Korean representatives have stated on more than one occasion – including to this author in Pyongyang in January 2009 – that the DPRK would have no need for nuclear weapons if the United States did not maintain a hostile policy toward their country. When U.S. envoy Stephen Bosworth, who is leading U.S. efforts at engagement with North Korea, visited Pyongyang in December 2009, North Korean officials reaffirmed their commitment to the 2005 joint statement on denuclearization. A joint editorial published on New Year’s Day 2010 by North Korea’s three major state-controlled newspapers speaks of Pyongyang’s desire to create “a lasting peace system on the Korean Peninsula and make it nuclear-free through dialogue and negotiations.”10 Indeed, this year Pyongyang has repeatedly stated that it wants to denuclearize the Korean Peninsula. Most recently, when Wang Jiarui, the head of China’s International Department of the Communist Party visited Pyongyang in early February 2010, Kim Jong Il told him of the DPRK’s willingness to participate in the stalled six-party talks and, significantly, its “persistent stance” to denuclearize the Korean Peninsula.11 This is fully consistent with what Kim Sung Il stated in a speech in which he repudiated the existence of nuclear weapons. During this speech, the elder Kim expressed his support for nuclear-weapons-free zones and a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula and stated, “The testing and production of nuclear weapons must be banned.”12

During Bosworth’s December trip to Pyongyang, North Korean officials also made clear their desire to sign a peace treaty. Pyongyang has prioritized the signing of a peace treaty, which it sees as a confidence- and trust-building mechanism, ahead of normalized relations with the United States, reasoning that normal bilateral relations with Washington would naturally follow a peace accord. In addition to allaying its concerns about a hostile U.S. policy, a peace accord would give North Korea international, legally binding assurance that its sovereignty would not be violated, something it values over all else. The importance that Pyongyang has attached to concluding a peace treaty is evident in that between the beginning of the New Year and February 7, the DPRK on nine different occasions has appealed for a peace treaty to replace the armistice agreement, including at North Korean embassies in Beijing and Moscow. Significantly, Pyongyang has stated: “The conclusion of a peace treaty would mean the first step toward creating a peaceful environment on the Korean Peninsula, stressing also that a peace treaty is not “different from the issue of the denuclearization of the peninsula.”13

North Korea has pressing economic reasons for pursuing a peace treaty. The DPRK’s economy is struggling, and with a peace treaty, the international sanctions imposed on North Korea would likely be lifted. Since the DPRK is unlikely to denuclearize while the sanctions imposed on it since 2006 by the United Nations Security Council because of its missile and nuclear testing are still in place, a peace treaty could therefore act as a catalyst to the denuclearization process. Furthermore, eventual rapprochement with the United States represents North Korea’s ticket to funds from international lending institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. A decrease in regional tensions could also open the door to improved relations between North Korea and Japan, including economic and financial benefits, and increased economic cooperation with South Korea – a precursor to the reunification of the Korean Peninsula.

Although relations between the two Koreas have hardly been problem-free of late, since August 2009, Pyongyang has made several conciliatory gestures toward South Korea. A peace treaty that becomes permanent and includes Seoul as a signatory would help stimulate North-South economic interaction. While the political unification of the Korean Peninsula remains distant, a peace treaty along with increased and sustained economic activities would build an important foundation for this.14

Japan-North Korean relations remain tense. In the absence of significant progress in resolving the abduction issue, Tokyo is unwilling to provide its share of the financial assistance promised to North Korea for its denuclearization, as required by the agreement reached at the six-party talks in February 2007. However, a conditional peace treaty that becomes permanent would fundamentally change the security environment in Northeast Asia. A marked reduction in regional tensions and especially an improvement in North Korea’s relations with Washington could create the right political conditions for Tokyo and Pyongyang to begin bilateral discussions that address the abduction issue and the “history problem” stemming from the Japanese colonization of the Korean Peninsula from 1910 to 1945. Moreover, with the change of administration from the Liberal Democratic Party to the Democratic Party of Japan in 2009, the chances are brighter for improving relations between Tokyo and Pyongyang. Japan-DPRK rapprochement would enable Tokyo to contribute its share of the financial package promised to Pyongyang during the six-party talks and to compensate North Korea for the problems associated with the Japanese colonization of the Korean Peninsula.

In return for denuclearization, North Korea will probably insist that Washington verify that the Korean Peninsula is free of U.S. nuclear weapons and that there be some reduction in the 28,500 American troops still in South Korea. But, with a conditional treaty in place, Washington could easily address these concerns.

South Korea would likely present a different kind of problem for the Obama administration with respect to U.S. troops stationed there. Especially now, with the conservative Lee Myung-bak as president, South Korea would likely resist U.S. troop reduction. Should this be the case, the Obama administration would need to make clear to Seoul that a peace treaty is a legally binding document that permanently ends all hostilities. What is more, in this case a peace treaty has the added benefit of denuclearizing the DPRK and creates the potential to help facilitate the unification of the peninsula.

The signing of a peace treaty would put an end to one of Asia’s most intractable and dangerous conflicts and allow Obama to reclaim the mantle of hope and change that inspired the world during his election campaign. Obama presently has nothing to show for his winning of the Nobel Peace Prize last year – indeed, he himself has recognized that the award was given in anticipation of what he will accomplish. Signing a peace treaty would represent a definitively new approach to U.S. foreign policy that would distinguish him from his predecessor.

For the United States, a conditional peace treaty is largely risk-free – and should not be tied to human rights issues in North Korea. Critics often charge that the Pyongyang regime is a menace to its people, but the human rights issue is an entirely separate matter and bringing it up now would only considerably delay – or perhaps eliminate – prospects for denuclearization.

Obama’s approach to date, prioritizing North Korea’s return to the six-party talks, has produced no results toward North Korea’s denuclearization. It matters little how denuclearization takes place – what matters is that it occurs, whether by relying on the six-party framework, bilateral discussions between Washington and Pyongyang, negotiations for a peace treaty, or some combination of these.

A conditional peace treaty that becomes permanent accomplishes Washington’s objective, which is to denuclearize North Korea. At the same time, a peace treaty satisfies Pyongyang’s criterion of “action for action” – a permanent peace treaty, which it wants, but only after denuclearization. This is win-win diplomacy: a chance for the United States to make progress in removing the DPRK’s nuclear weapons and its capability to produce them, while facilitating the peace, and perhaps ultimately unification of the Korean Peninsula. Obama should seize the opportunity.

Anthony DiFilippo is Professor of Sociology at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. His most recent book is Japan’s Nuclear Disarmament Policy and the U.S. Security Umbrella (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006). He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Anthony DiFilippo, “The Peace Deal Obama Should Make: Toward a U.S.-North Korea Peace Treaty,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 7-4-10, February 15, 2010.

Notes

1 The Text of the Korean War Armistice Agreement, July 27, 1953, accessed here.

2 See U.S. Department of State, John Glennon, ed., Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952-1954: The Geneva Conference, Volume XVI (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1952-1954), pp. 1-394, accessed here; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, The Geneva Conference, Beijing, November 17, 2000; Kim Byong Hong, “North Korea’s Perspective on the U.S.-North Korea Peace Treaty,” Journal of Northeast Asian Studies, vol. 13, no.4, Winter 1994, pp. 85-89.

3 U.S. Department of State, Press Statement by Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright, North Korea: Four Party Talks, Washington D.C., June 30, 1997, accessed here.

4 For example, during the first North-South Summit held in June 2000, Kim Jong Il supposedly said to South Korean President Kim Dae-jung that U.S. forces in South Korea are not especially bad. See, “North Korea to Revise Party Charter in Exchange for End to South’s Security Law,” Yonhap News, June 20, 2000; “Kim Jong Il Agreed on Need for US Troops in South – NK Leader Also Promised to Revise Workers’ Party Platform,” The Korea Times, June 21, 2000.

5 “DPRK Diplomats have Little to do for DPRK-U.S. Relations,” Korean Central News Agency, December 7, 1998.

6 Office of the Spokesman, U.S. Department of State, Joint U.S.-DPRK Statement on International Terrorism, Washington, D.C., October 6, 2000, accessed here.

7 Office of the Spokesman, U.S. Department of State, U.S.-DPRK Joint Communiqué, Washington, D.C., October 12, 2000, accessed here.

8 “Conclusion of Non-aggression Treaty between the DPRK and the U.S. Called For,” Korean Central News Agency, October 25, 2002.

9 The Obama administration has several options available to pursue a peace treaty. One is ratification by the U.S. Senate by a two-thirds majority. Another is an Executive Agreement, which the president orders and does not require Senate or Congressional approval. Like one ratified by the Senate, a peace treaty that results from an Executive Agreement is legally binding and recognized by international law. For these and other options, see Congressional Research Service, Treaties and Other International Agreements: The Role of the United States Senate (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, January 2001) here.

10 “Joint New Year Editorial,” Korean Central News Agency, January 1, 2010.

11 “DPRK Top Leader Reiterates Denuclearization of Korean Peninsula,” Xinhua, February 9, 2010; “N. Korea’s Kim Reiterates Call for Denuclearization of Peninsula,” Kyodo News, February 9, 2010.

12 Kim Il Sung, For a Free and Peaceful New World, Speech given to the Inter-Parliamentary Conference, Pyongyang, 1991.

13 “US Urged to Make Decision to Replace AA by Peace Treaty,” Korean Central News Agency, January 21, 2010.

14 Goohoon Kwon, “A United Korea? Reassessing North Korea Risks (Part 1),” Global Economics Paper No: 188, Goldman Sachs, New York, September 21, 2009.