Revisiting Postwar Taxation in Japan and its Contemporary Implications

Elliot Brownlee talks with Andrew DeWit

For several weeks of the extraordinarily hot summer of 2010, Japan was embroiled in a stand-off between Prime Minister Kan Naoto, representing fiscal austerity, and Ozawa Ichiro, representing more spendthrift Keynesianism. Both sought the presidency of the DPJ in the September 14th party elections, with the winner becoming PM. Faced with dismal poll results in advance of the July Upper House elections, Kan was forced to backtrack on his commitment to raise the consumption tax and cut spending in order to balance the budget. But that remained the core of his policy over the long haul, with an immediate 10% cut to all government ministries now back on the table. By contrast, Ozawa preferred to throw money around in order to stimulate Japan’s lagging economy and garner votes.

With Kan strongly reaffirmed as PM and having reduced the ranks of Ozawa’s supporters in the cabinet, fiscal austerity appears to be in the offing.

But this drama is not merely Japanese. Much of the world, especially the developed world, is facing roughly the same choices. Politics is aground on the rocks of whether to spend more to stimulate economies sliding into recession/depression and deflation, or whether to rein in spending and increase taxes, especially regressive taxes, in order to cut swollen public sector deficits. Talk of more equitable, efficient and sustainable public finance is still confined to the margins of the public debate. It will surely move closer to the centre of our concerns as the fallout from fiscal austerity undermines social security, scientific research and other essential elements of social stability and economic competitiveness. But rather than wait for more hard knocks, we should be turning to history as a guide out of the current impasse.

Elliot Brownlee, Emeritus Professor of economic history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, is a student of fiscal history and what it might teach us about present challenges. He is author and editor of several noted works on fiscal and economic history in the US, with an especially deep understanding of the political history of the progressive income tax. On August 21st, we talked at his home about his book-in-progress on Carl Shoup, who played a critical role in shaping Occupation fiscal policies. This short article is the substance of that interview.

|

Elliot Brownlee |

Elliot has been writing detailed accounts of what we might learn from the US-inspired Shoup tax missions (1949-1950) and subsequent tax reforms in postwar Japan. The Shoup reforms were among the most ambitious efforts ever to redraw a fiscal system. Indeed, their clarity and balanced approach to securing equity and growth has seen them continue, throughout the postwar years, to serve as a point of departure for Japanese debates on tax reforms. This continued relevance of the Shoup Report is despite the fact that the Shoup reforms, per se, were largely gutted in practice. As fiscal crises deepen and spread across the industrialized world, the fundamental precepts of Shoup, and perhaps even the letter of the Shoup recommendations themselves, are being looked to for lessons in the present.

Elliot has in fact become the linchpin in an international effort to build on Shoup’s approach from the perspective of comparative history and tease out lessons for contemporary policy challenges. This primarily Japanese and American collaboration of scholars has a volume in preparation, edited by Ide Eisaku of Keio University, Fukagai Yasunori of Yokohama National University, and Elliot. This edited book, separate from Elliot’s own single-author study of Shoup, is based on papers presented at a joint conference held last December at Yokohama National University and Keio University in Tokyo. The conference focused on the larger historical significance of Shoup, and served both to mark the 60th anniversary of the Shoup Mission as well as launch the international collaboration to reconsider this fiscal history. It is a very ambitious undertaking. But far more ambitious is the prospect of paying down the gargantuan mountains of debt rising up in the developed world. This challenge will be more readily met if the ground is prepared through critical thinking on such matters as equity, fiscal sustainability and the proper construction of the tax system. Cross-national collaboration on examining the lessons of the Shoup mission will help prepare this ground. Any lessons that can be drawn from the Shoup reforms themselves, as well as from this cross-country intellectual collaboration in the present, are almost certain to be of great value.

One of Elliott’s trademarks as an institutionalist historian is the use of painstaking archival research to illuminate the historical context and content of tax reforms and other policies that continue to shape the present. His new book explores a number of hitherto unknown aspects of the Occupation. Elliot is opening new windows on the enormous tensions played out in the relations among Douglas MacArthur, Joseph Dodge, and Carl Shoup, as well as among the Occupation and the various interests composing the Japanese political and bureaucratic authorities.

Elliot notes that he was especially fortunate in finding excellent primary sources for this work. In 2007, he got a very welcome surprise when he arrived in Japan to continue his research on Shoup, whose private papers he had long been searching for. On arrival, Elliot was informed by Shoup’s family as well as by then-Yokohama National University Professor Ide Eisaku (now at Keio University) that Shoup’s personal archive was in the hands of the Yokohama University Library. Elliott promptly investigated and found a gold mine. The entire, enormous collection had been there for some years and was still lying in nearly 500 boxes, seldom used and largely uncatalogued. Some of the materials had obviously been untouched for decades.

And so Elliot set to work, reading among Shoup’s papers while seeking to unravel the mystery of Shoup’s means of organizing his personal records and research materials. A lot of the new insights into the Shoup reforms and their context are the fruit of perusing these papers as well as comparing impressions and insights gleaned from them with the developed historical record and yet another look at the archives left by Joseph Dodge, Dwight MacArthur and other key figures of the era.

Among the myriad reasons to reconsider Shoup are not only the Shoup recommendations’ monumental importance as a statement of Haig-Simon progressive income tax-centred equity and our collective need for a comprehensive, historical approach in seeking solutions to current fiscal crises. There are also a host of still-unexplored, or inadequately studied, issues pertaining to Shoup and the US-Japan connection. One feature of particular interest to Elliott in this comparison of Japan and the United States is the institutional roots of tax resistance. Both countries feature unusually strong tax resistance ideologies and movements, when viewed against the backdrop of fiscal politics among the advanced industrialized nations. Both countries also share a postwar history of broad-based, progressive income taxation at the core of their fiscal structures. These fiscal systems provided massive revenue flows in both countries, leaving fiscal politics largely centered on how to extend tax breaks in the policymaking process.

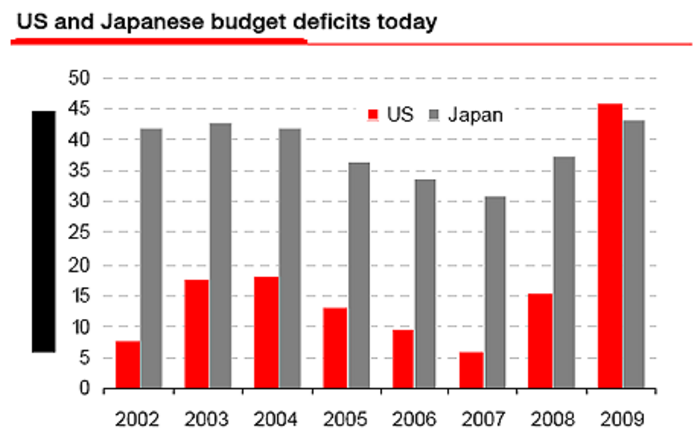

Despite this legacy, cutting too deeply into the overall tax base has taken a huge fiscal toll in both countries. In recent years, they have found it extremely difficult to fund their public sectors adequately. In Japan, problematic tax policymaking has led to an inordinately low tax burden and a gross public sector debt that is nearing 200% of GDP. And in the United States, the achievement of a fiscal surplus during the latter Clinton years was followed by very deep (and very inequitable) tax cuts that have contributed greatly to the fiscal crisis confronting America.

US and Japanese Budget Deficits, 2002-2009. Japan’s budget deficits surpassed 200% of GDP in 2009. Forex Blog Jan 13, 2010, link.

One of the major questions is the extent to which the Shoup reform program itself contributed to the fiscal resistance that plagues contemporary Japan. The aversion to adequate taxation cannot be explained away as a natural outcome of individual dislike of paying taxes. There are plenty of countries—the Scandinavian countries and much of Western Europe, for example—where comparatively high tax burdens elicit minimal fiscal resistance, whereas the relatively low tax burdens in Japan and the United States elicit strong fiscal resistance. If tax resistance were simply the product of economic rationality, then one would expect low tax burdens in the United States and Japan to be coupled with relatively low tax resistance and high tax burdens in such countries as Sweden to provoke strong tax resistance. Since the degree of tax resistance is in fact entirely contrary to this, there would appear to be historical-institutional forces at work.

We also have to ask the extent to which Japanese tax resistance, so far as it has historical roots, is due to a general revulsion towards the wartime regime. After all, the militarists brought truly onerous taxation, especially in their 1940 reforms, as well as enormous destruction and humiliating defeat. Perhaps this was formative in institutionalizing antagonism towards the return of well-funded government. On the other hand, tax resistance might have been primarily the product of the postwar Occupation. One of the salient facts about the early Occupation is that it rapidly expanded the tax base and deployed rather coercive means, including the use of military vehicles and personnel, to collect those revenues.

This latter left an impression of the Occupation as fiscal extraction, and clearly affected the Shoup reforms. Elliot argues that

“the problem in Japan was confusing the role of the 8th Army and its brown cars, its Jeeps, with the role of the Shoup Mission. In short, the history of that early effort to collect taxes during the Occupation somehow became confused with the Shoup recommendations. And it’s tragic in a way, as Shoup sought to create a tax system in which the public would have confidence, one in which voluntary compliance would be high. Shoup was trying to move away from the coercive tax system that had characterized the early years of the Occupation. He wanted to move along towards a system that would be worthy of a democracy.”

In fact, one of Shoup’s main concerns was to put equity at the center of the Japanese tax system, precisely in order to gain public support. He was also very keen to increase the transparency of the tax system so that the Japanese public would see the benefits they were deriving on the expenditure side. He focused on the revenue side, to achieve these objectives because he was not mandated to make recommendations for the expenditure side of the budget.

Elliot believes that

“if the full body of the Shoup recommendations had been adopted immediately in 1949 and 1950, then smart American tax experts and their Japanese counterparts might have had the time to work together so as to secure the implementation of the system that Shoup had in mind. Had they had more time, Shoup might have formed the basis of a system of government that would have received the respect and trust of the Japanese public. One of the major problems, however, was that the Occupation ended soon after, which limited the time available to craft the means for working out the recommendations. Particularly problematic was that Shoup included many technically difficult reforms. The proposal for a value-added tax was the first of its kind anywhere, and so presented considerable technical problems. Also, the Shoup proposals for reform to intergovernmental fiscal relations, while they were less challenging in technical terms, were very challenging politically.”

Another hurdle for the Shoup reforms were the divisions within the Occupation itself. Elliot’s work provides a much sharper picture of how the division between Shoup and Dodge was not one in which idealistic tax reform confronted the practical realities of stabilizing the economy. Current understanding of this period sees Shoup’s ambitions running up against the “Dodge Line” of balanced budgeting and other rigid targets. But in reality it was the New Deal approach to taxation and the welfare state that clashed with the classic Republican emphasis on small, minimally redistributive, and fiscally responsible government. Dodge not only “thought the effort to democratize Japan bordered on the absurd, he also was fundamentally hostile to social democracy,” whether in the US or Japan, and so quite antipathetic to Shoup’s goals.

The splits between Shoup and Dodge extended broadly into the Occupation itself. The Occupation’s departments of Internal Revenue and Finance, for example, mirrored these splits. The former was sympathetic to Shoup while the latter was antagonistic. Elliot’s work has also uncovered how Dodge skillfully cultivated personal ties with MacArthur’s most trusted associates. And he shows in detail how these divisions in the Occupation antedate the “reverse course,” when the rise of the Cold War profoundly shifted the overall US view of what to do with Japan. The reverse course has long been trotted out to explain why the Shoup reforms failed, but the divisions that seem most telling in the fate of Shoup and tax reform long predated it.

Shoup sought to increase public confidence in government and create a strong and equitable fiscal basis to expand the welfare state. Dodge, on the other hand, was a strong proponent of shrinking the welfare state that was emerging in the United States. Dodge was thus ideologically disinclined to support efforts to increase public confidence in the tax system. Let us be clear that Dodge was not in the mold of contemporary Republicans, who since Reagan have stressed a policy of tax cuts to “starve the beast” of the welfare state that was built in postwar America. Dodge was instead a classic prewar Republican who emphasized minimal state commitments and opposed deficits as a matter of principle. Elliot’s research clearly reveals how these ideological differences, coupled with the asymmetric influence of Shoup and Dodge, shaped the outcomes of the Shoup reforms.

Shoup did not enjoy a strong hand in this context, and he was determined not to confront Dodge in public. Hence it often appeared that the two were working in agreement, almost in consort. Behind the scenes, however, there was a great deal of tension. Moreover, Dodge was working closely with Japanese bureaucrats who opposed much of the spirit and the letter of the Shoup reforms. Small wonder, then, that Dodge refused to do what he could have done, which was order the Japanese to implement Shoup’s reforms.

MacArthur too could have ordered the Japanese government to implement the Shoup reforms, but opted not to. There appear to be two main reasons for this. One was that he was reluctant to impose anything on the Japanese so as not to undermine the transition to democracy, which was of course MacArthur’s overriding ambition for the Occupation. The second reason was that opting to use a decree would have put MacArthur in direct conflict with Dodge. MacArthur instead hoped to finesse the problem. He counted on his endorsement of the Shoup reforms in principle as being enough to get the ball rolling. In short, he gambled that the momentum would allow the Occupation’s Internal Revenue Division, staffed by such sharp minds as Martin Bronfenbrenner and supported by Shoup’s ongoing mission, to overcome the institutional obstacles to reform.

This kind of thinking was not so unrealistic. Shoup himself in late 1949 and 1950 was counting on Dodge to advocate the entire reform package to the Japanese government. From late 1949, with the Shoup Mission still under way, they were deeply disappointed when Dodge failed to do this. Dodge instead advocated measures that the Japanese government itself favoured, and failed notably to support those that the Japanese government was dubious about.

One salient example of the latter was the provisions for reforming the fiscal base of local government. Shoup wanted to secure strong and reasonably autonomous local government, seeing it as the key agency for delivering services in an emergent welfare state. He also sought to strip the innumerable strings attached to intergovernmental grants, and dramatically reduce their role by adopting a redistributive system of block grants. The Japanese central government, not surprisingly, resolutely opposed these decentralizing reforms. Dodge came down decisively in favor of the Japanese government (most notably the Prime Minister and Minister of Finance) on these critical issues.

Elliot notes that it is very difficult, of course, to calculate with precision the effect of Dodge’s position on the Shoup reforms. But he believes Dodge’s hostility was very significant in tipping the balance against the value-added tax as well as the block grants. Dodge’s opposition to comprehensive reform also allowed for modifications to the broad-based income tax that the Japanese government did adopt.

It is important to keep in mind here that at the time Japanese party politics was developing a very strong anti-tax focus. Virtually all the parties competed to strongly oppose taxes, and this carried over naturally to the subsequent denunciations of the Shoup reforms. Characteristic of the slogans employed was the idea that the Shoup reforms were treating the Japanese as guinea pigs because the value-added tax was a new and untried tax. The question is whether this kind of hostility was simply inevitable or was largely set in motion by the earlier style of the Occupation, as well as the failure of such critical actors as Dodge, to support the Shoup reforms.

This background of the early Occupation should not be overlooked. The early years of the occupation increased taxation, centered on the income tax, and implemented a system of surveillance to maximize tax revenues. This was all done by the Army, and to a defeated populace generally struggling at the margins of existence, it could hardly have seemed a laudable democratization. This is one reason Shoup focused so much on reforming aspects of the tax system that were likely to engender hostility from the Japanese public. Another important mechanism to this end was Shoup’s effort to create the means, in spite of not being able to analyze the expenditure side of the budget, to show taxpayers the relationship between what they paid and what they received in terms of services. A major element of this effort was transparency in revenue streams. The value-added tax was the most controversial element of the Shoup reforms, but it was critical to the overall effort since it was to supply service-providing local governments with a stable fiscal base. The argument here was that local governments are closer to the people, and that the services delivered by them are more visible and more likely to conform to taxpayer preferences.

But the Japanese public, as a result of Shoup’s inadequate mandate (i.e., his inability to make recommendations on expenditures as well as revenues) and other factors, including Dodge’s hostility, were never given a program that explicitly linked revenues to expenditures. They never actually got to see that they were indeed getting a more democratic fiscal system. The Japanese government is also deeply implicated in this failure, as it was especially hostile to decentralizing reforms (which even today remain a political challenge in Japan). Simply put, the Japanese government wanted to maintain national control of local government and local services, and made sure it did. As Elliot succinctly puts it, “of course one of the outcomes of that victory is what we think of as the modern construction state in Japan.”

Thus the confrontation between Shoup and Dodge was not one between centralized, big government and decentralized, small government. As Elliot points out, this fact becomes even clearer if we look at the financial policy that these two actors advocated. Shoup opposed special favours for investment banks and wanted what he saw as US-style capital markets in Japan. But Dodge was strongly supportive of channeling funds through the banking system and directing their allocation through collaboration between the public and private sectors. Thus Dodge turns out to have been committed to what became one of the key features of Japan’s postwar high growth system. Recall that this system was marked by state interventionism and industrial policy on behalf of producers as opposed to citizens and consumers. Shoup was an advocate of decentralization on virtually all fronts, including investment finance and public finance.

An additional facet that is fascinating, and which Elliot explores in detail, is that MacArthur turns out to have been a skilled amateur historian of taxation. In fact, he was instrumental in organizing the first mission on taxation to Japan, whose chief was the US treasury point man Harold Moss. MacArthur was not as keen on the welfare state as Shoup, but his equity-oriented approach to taxation was quite similar. The instructions that MacArthur gave to Moss run in a straight line from the prewar equity arguments to the Shoup mission. MacArthur maintained a strong interest in tax reform all the way through the eruption of the Cold War and until the Korean War. Once the Korean War broke out, however, it became impossible for him to maintain significant attention on tax reform. So by the time of the second Shoup mission in 1950, MacArthur was unable to devote much time to the process and recommendations. Elliot argues persuasively that MacArthur would likely have accomplished more, especially in terms of arm-twisting with the Japanese Government, had it not been for the Korean War.

One could also see a line running from the 1940 reforms to the early postwar reforms, with their dispatch of the 8th Army’s Military Police to enforce collection. Absent a clear and decisive break with this past, the Shoup reforms risked being seen as part of it. From the perspective of the Japanese taxpaying public, it surely appeared to be one long continuity. And surely that perception of continuity underlies a great deal of taxpayer hostility throughout the postwar years, raising the probability that the hostility became institutionalized in party politics and the political culture more generally.

So we return to the key point of entrenched tax resistance in Japan and the United States. Both countries relied heavily on income taxes and especially on progressive income taxes at the center of their fiscal regimes in the postwar years. Economic growth produced ample revenue, allowing both states to develop extensive expenditure commitments to, respectively, defense and construction. Both systems delivered the capacity to sustain significant central governments while at the same time allowing politicians to cut taxes. Tax cutting is not something new with George W. Bush. The strategies have changed, but the tax tactics have remained pretty consistent throughout the postwar in both countries.

And now both countries would appear to have exhausted the limits of their postwar fiscal regimes and associated fiscal politics. A fiscal revolution had better be in the cards. Elliot argues that the act of looking at history almost inevitably sheds light on the problems of the present. Perhaps most important, the history of the Shoup mission suggests to him that to build popular consensus for a program of significant tax increases, the Japanese and American governments need to find ways to move the discussion of tax issues away from the raw self-interest of classes or groups to the traditional goals of tax reform—fairness, economic efficiency, and transparency.

U.S. Economic historian Elliot Brownlee is professor emeritus at the Department of History, UC Santa Barbara. A specialist on comparative financial and fiscal history, including the comparative study of US and Japanese fiscal systems, his works include Funding the Modern American State: The Rise and Fall of the Era of Easy Finance, 1941-1995 and several works on the Shoup Mission to occupied Japan.

Andrew DeWit is Professor of the Political Economy of Public Finance, Rikkyo University and an Asia-Pacific Journal coordinator. With Kaneko Masaru, he is the coauthor of Global Financial Crisis.

Recommended citation: Elliot Brownlee and Andrew DeWit, “Revisiting Postwar Taxation in Japan and its Contemporary Implications,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 39-2-10, September 27, 2010.