By Chinese standards, the city of Yanji is rather small, with a population of nearly 400,000. About a third of them are ethnic Koreans: Yanji is the capital of Yanbian autonomous prefecture in the northeastern province of Jilin, the ethnic home of the large Korean minority in the area. The prefecture is close to the borders of North Korea and Russia.

Yanji City shown (in yellow) in Yanbian Prefecture, Jilin Province. The Korean and Russian border is indicated in blue.

The city streets and shops have signs both in Korean and Chinese, the people (well, many of them) speak Korean among themselves, and restaurants advertise dog meat, a traditional Korean delicacy. But it also feels different from South and North Korea. Nowadays Yanji is much too poor if compared with the South and much too rich if measured against meager North Korean standards.

The Korean migration to the area is a relatively recent phenomenon: it began as a trickle in the 1880s, and developed into a large flow by the early 1920s. Some of those settlers fled the persecution of Japanese colonial occupiers at home, but many more were attracted by fertile lands easily available to migrant farmers in what then was known as Manchuria.

An overwhelming majority of settlers, some 80%, came from areas that after 1945 became part of North Korea. During the Chinese Civil War, most local Koreans sided with the communists, which helped boost their standing after 1949. The local Koreans were officially recognized as a “minority nationality”, and in 1952 the entire area was made into an autonomous prefecture, with the Korean language co-official with Mandarin.

The newly established district occupied an area of 42,700 square kilometers, just a bit less than half the area of South Korea, but its population is just 2.2 million. South Korea has 48 million people, so the density of population in Yanbian is remarkably low. Indeed, while traveling through the area one can drive several kilometers without encountering any signs of human settlement – a picture that is unthinkable in most of South Korea or coastal China.

In 1945 about 1.7 million Koreans lived in China, overwhelmingly in its northeastern area. About 500,000 of those chose to move back to Korea in the late 1940s, but a million or so decided to stay. Nowadays, the Korean population has reached 2 million, of whom some 800,000 reside in Yanbian. This makes ethnic Koreans the 14th largest ethnic minority in China.

Economically, the area has not been very successful compared to the coastal areas of Central China – perhaps because it is landlocked, so the import-oriented development strategy does not really work there. Sometimes in the villages around the city one can even come across a derelict hut with a thatched roof – a sight that is almost impossible to see more prosperous areas of China. Still, changes are everywhere: the slums are being demolished and giving way to new, posh apartment complexes, construction is booming, the number of newly built hotels is astonishing, and good roads crisscross the area, though motor traffic is still very thin.

Yanji City, the capital of Yanbian

Yanji City, the capital of Yanbian

Beijing’s policy toward ethnic Koreans has always been somewhat contradictory. On one hand, the Chinese central government follows the Leninist principles it learned from the Soviet Union. According to these principles, the ethnic minorities should be given manifold privileges, often at the expense of the majority group.

Indeed, this is frequently the case with the ethnic Koreans. But there were periods of unease and even open persecution, especially in the tumultuous decade of Mao’s Cultural Revolution beginning in 1966. A middle-aged ethnic-Korean businessman told me, “Back in the late 1960s, I seldom saw my parents. Because they were members of an ethnic minority, they had to go to ideological-struggle sessions every day and had to stay until very late.”

However, that period was an exception. The same person, who said he is not a fan of the current Chinese system, responded when asked about discrimination: “Discrimination? Well, almost none, to be frank. They appoint some Han Chinese officials to supervise the administration, but basically I don’t think Korean people here have problems with promotions or business because of their ethnicity. Sometimes being a minority even helps a bit – it’s easier to get into a university if you come from a minority group.”

It is clear that many Korean community cultural institutions rely on generous subsidies from the central government. The Chinese state sponsors a large network of the Korean-language schools, so until recently nearly all Korean children received secondary education in their ancestors’ tongue. If they wish, they can attend Yanbian University, where ethnic Koreans receive preferential treatment in the entrance exams.

The local television network broadcasts in Korean and the newsstands in the area sell a number of Korean-language periodicals. Some of these publications hardly need sponsorship, since they deal with the ever popular topics of sex, crime and violence. The sheer abundance of this pulp fiction serves as another proof that the Korean language is quite alive in the area: who would buy these magazines otherwise? However, some publications are clearly unviable without government funds. There are, for example, official newspapers, which run the usual boring content of a local Chinese government media. However, some of those sponsored publications are far more serious, like Changbaeksan, a quarterly literary magazine which publishes high-brow fiction by local authors. Taking into consideration the limited size of its audience, such a journal would not survive without public money.

A local law requires every street sign in the prefecture to be written in both Korean and Chinese, and it explicitly stipulates that Korean letters should not be smaller or placed below the Chinese characters. This even applies to advertisements.

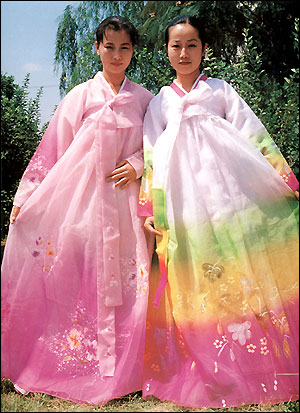

The Korean heritage (or rather those parts of the heritage that are deemed politically safe) is much flaunted in the area because it is one of factors that make Yanji attractive to potential tourists. So Korean restaurants are everywhere and local advertisements frequently use images of beautiful “ethnic” girls clad in the Korean national dress or hanbok. Sometimes instead of images they use real girls to greet the visitors (more than once I was surprised to discover that some of those girls cannot utter a single word in Korean).

Women in Korean national dress

Women in Korean national dress

However, it would be a mistake to depict Chinese policy in the area as an ideal to be emulated. The potential threat of irredentism has never been completely forgotten, and it is an open secret that radical Korean nationalists have dreamed of annexing this area since at least the early 1900s. They often say Yanbian is actually a “third Korea”, so it should be included in a Greater Korea that they believe will emerge one day.[1]

Until recently irredentism was not much of a threat, since the impoverished and grotesquely dictatorial North Korean regime could not inspire much longing for the lost homeland among the Chinese Koreans. Perhaps most local Koreans share the feelings of a middle-aged Korean with whom I had a long talk in the town of Tumen on the North Korean border. While pointing to the barren hills of North Korea, easily seen from a restaurant window, he said, “I am so lucky that my grandparents chose to get out of that place. I think we all would be dead had our grandfather stayed. It is such an awful place. I do not understand how they manage to survive in North Korea.”

This seems to be a common feeling toward North Korea among Yanbian Koreans. There might be a lot of genuine sympathy, as demonstrated in the late 1990s at the height of North Korea’s great famine, when there was widespread grassroots support for the illegal migrants from that country. Around 1999, an estimated 200-300,000 North Korean refugees were hiding in this area, and many locals felt great sympathy for their plight. Without this sympathy and support their survival would have been far more difficult, or even impossible. However, in most cases local Koreans see the North Korean regime as an object of contempt and ridicule, and its unwillingness to emulate the Chinese example is often mentioned as the major reason for the disastrous situation of the country.

Still, the cross-border movement never stopped completely. In the early 1960s when the Chinese economy was in very bad shape after the “Great Leap Forward”, many ethnic Koreans fled to North Korea where they were welcomed, provided with meager (but still livable) food rations and given jobs. Some of them eventually returned to China, but others chose to stay. From the early 1980s, the ethnic Koreans were allowed to visit their relatives in the North. Such trips became quite common, and served to stimulate cross border trade. This trade still goes on, often illegally, since it is not too difficult to smuggle the goods across the narrow and shallow borderland waterways. The Chinese merchants, overwhelmingly members of the ethnic Korean community, largely sell household items, garments and footwear, while purchasing dried seafood. There are even specialized markets which cater to North Korean demands. Still, this trade is limited, unlikely to ever seriously influence the regional economy in China’s Northeast. Across the border, in North Korea, its impact is much larger.

However, in 1992 China established formal diplomatic relations with prosperous South Korea, and soon Yanbian was flooded with South Korean business people, missionaries, students and tourists. Most were attracted by the opportunities to do business without dealing with a language barrier, but some also began to preach the nationalist gospel. Their work was made much easier by the fact that South Korea by the 1990s had come to be seen not as a land of destitution but one of prosperity and opportunity. South Korean nationalists love to stress that the area of Yanbian once was part of the ancient Korean kingdom of Koguryo that lasted 700 years, from 57 BC to AD 668. Koguryo is presented by them – as well as by many other Koreans outside of the area – as the most successful of the three ancient Korean kingdoms.

Travel poster advertising for Yanbian

Therefore, Chinese authorities are on guard against this nationalist fervor to ensure that Korean-language education does not mean education in the spirit of Korean nationalism. At the Korean schools, children study exactly the same curriculum as their peers in the Chinese-language schools. Their textbooks are exact translations of the Chinese textbooks used at the same levels.

“We are a minority group of China, China is our country, so there is no need to study Korean history or literature,” one ethnic Korean told me. “When they teach national history at our schools, it means the history of China, and China only.”

As a result, the younger generations of Koreans are increasingly out of touch with their Korean heritage. Ko Kyong-su, a professor at Yanbian university and an ethnic Korean, remarked: “Nowadays, the Korean youngsters here do not learn about Ch’unhyang and Hong Kil-dong [characters from Korean classical novels] until they enter college, and only then if they chose to specialize in Korean studies.”

Yanbian University

Yanbian University

To what extent does this dualistic policy of support and restrictions work? This is a somewhat difficult question, but it seems that the overwhelming majority of local Koreans indeed see themselves as “hyphenated Chinese”, not as proud overseas citizens of either Korean state. Their loyalties are, in most cases, firmly with Beijing.

Still, it is clear that the ongoing nationalist propaganda produces some response. A number of times Korean acquaintances inquired whether I had seen the Koguryo remains, and once a woman in her early 30s, a fellow traveler on a train from Yanji to Shenyang, said nostalgically, “Two thousand years ago this used to be Korean land. We were so big then!”

This is not exactly a feeling that Chinese authorities would like to nurture, so it comes as no surprise that in official publications, Koguryo is mentioned as a “minority regime” that once existed as part of multi-ethnic but unified Chinese nation. The Chinese nation, according to Beijing propagandists and court historians, existed since time immemorial.

At the same time, the booming economic ties with South Korea bring benefits to the local community. Indeed, South Koreans like to come to the area where so many important events of Korean history once took place, and they feel intrigued about a possibility of a “little Korea” located overseas. The North Korean border also serves as an attraction, so Yanji has a number of new hotels, all built in recent years, and all overbooked at the tourist season. The Yanji University has some 500 foreign students, overwhelmingly from South Korea.

In turn, many Yanbian inhabitants of Yanbian have traveled to the South. According to the Immigration Service of South Korea, in late 2006 some 236,000 ethnic Koreans from China resided in South Korea on long-term or permanent basis.[2] This means that one out of nine Koreans at any given moment is working, studying or doing business in South Korea. Doubtlessly, their fluency in Korean helps a lot to find some jobs there.

Frequent visits to Seoul seem to create rather ambiguous feelings towards the South. On one hand, ethnic Koreans are clearly proud to be associated with such a powerful and economically successful country. At the same time, a vast majority of them end up doing dirty jobs of different kinds, the jobs which are known in Seoul as “3D” (dirty, difficult, dangerous). Their employers are small-scale businessmen who often are not reliable, so delayed payments and broken promises are rather common. The workers also suffer from subtle discrimination, since in a status-conscious South Korean society they are at the very bottom of the pecking order. Finally, they also discover that decades of existence in a different society have made them very unlike the Koreans of South Korea. Hence, in a sense it seems that feelings of a separate identity are reinforced by such an experience. As a Yanbian PhD student in Seoul, commented: “I am not saying that we are better than South Korean Koreans. But we are different. The longer I live here, the more I feel this. I am a Chinese. Of Korean extraction, and with great interest in things Korean, but still Chinese.”

Better educated Koreans frequently leave Yanbian and move to other areas of China to take up jobs as foremen or low-level managers at Korean-owned companies. Their ability to communicate freely in two languages, combined with familiarity with two cultures make them ideal intermediaries. This is a good income, too: a recent high school graduate can realistically hope to receive a monthly salary of some 2000 yuan in Yanbian while as a supervisor at a Korean factory he or she is likely to earn 4,000 yuan or more. However, once again: the experience of working together with South Korean businessmen is a mixed one, at times making ethnic Korean workers somewhat hostile to their employees and reinforcing their Chinese identity.

In spite of all those problems and potential challenges, until recently Yanbian prefecture could be seen as a virtual poster case for China’s “nationality politics”. Indeed, unlike the situation in Russia, Japan or the United States – three other major countries with sizable ethnic-Korean communities – the Korean-Chinese have remained fluent in their ancestors’ language, though they overwhelmingly belong to the third or even fourth generation of immigrants. They are also quite socially successful. Indeed, if measured by such indicators as physical quality-of-life index (PQLI), in 1990 Koreans were the second-most-prosperous ethnic group in China.[3]

However, nowadays things are not that rosy – at least if judged from Korean nationalist perspectives. Beginning in the mid-1990s, the ethnic Korean population of Yanbian began to shrink, with its share dropping to 36.3% in 2000 (from 60.2% in 1953), and is still falling. It has been predicted that if current trends continue, this percentage will drop to merely 25% by 2020.[4]

Local Korean schools are being closed for lack of students, and Korean parents are increasingly unwilling to send their children to ethnic schools. Until a decade ago, almost every Korean family chose to educate their children at a Korean school, but this is no longer the case. The number of children enrolled in Korean language primary schools in 2000 was just 45.2% of the 1996 total. In the 1990-2000 period, 4,200 Korean teachers, 53% of the total, left their jobs because of school closures.[5] This does not mean that Koreans are more poorly educated – on the contrary, the past two decades have witnessed a great education boom. But their education is increasingly conducted in Chinese, not Korean.

This is not a result of some deliberate discrimination or the cunning policies of Beijing. No doubt some Chinese policy planners might feel a bit of relief when they see how a potentially “separatist” area is losing its explosive potential, but it seems they have done nothing to speed up such a development. Rather, Koreans are becoming the victims of their own social success.

In the past, the aspirations of the average ethnic Korean was to graduate from a high school, settle down in his or her local village, and become a farmer who could afford to have rice at every meal. Now, success is increasingly associated with a university degree. However, university education is in Chinese, as are the entrance exams. Korean parents know that Chinese-language schooling gives their children educational advantages. At the same time, their sense of identity seems to have been sufficiently eroded that few choose to reinforce their children’s “Koreanness” at the cost of putting their potential careers at risks. Hence, there is a steady increase in numbers of Korean parents who choose to send their children to a Chinese school. In 1987, only 3.4% of ethnic Korean students attended a Chinese primary school. In 2000 the figure increased to 11.2%.[6]

This process is easy to see even without statistics. It is clear that a large proportion of younger people speak Korean, but it is also clear that many youngsters do not feel comfortable communicating in their parents’ tongue, and are happy to switch back to Chinese at the first opportunity. It was instructive to see two Korean families who sat next to me on a train: the youngsters, in their 20s, spoke Korean to the parents but preferred Chinese among themselves. The same trend – slow decline in language fluency of the younger generation – has been noted by some academic research on the issue.[7] It is a trend clearly visible in other parts of China and among immigrant families in many other societies.

Another part of the crisis is the low fertility rate of the ethnic Koreans. The Koreans’ birth rate has always been lower than that of the Han Chinese, even though, as an ethnic minority, they are exempt from the “one-child policy”. In 2000, the average Korean woman in Yanbian had 1.01 births in her lifetime. This again reflects the higher education levels of the ethnic Koreans: better-educated groups in China as in many other countries tend to have fewer children.

Migration is also taking its toll as growing of social aspirations leads to increased migration (one cannot go too far if one remains in the Yanbian backwater). A large number of ethnic Koreans have moved away from their village communities. Some have gone to South Korea, but for most the destinations of choice are large Chinese cities, such as Shenyang or Beijing. While in the city, Korean settlers tend to maintain close relations with other Koreans and even create ethnic quarters, but they still live in a Chinese-language environment, and speak less Korean. The chances of marriage with Han Chinese are high, and children from such marriages are usually monolingual – Chinese.

So it seems that the days of a distinctive “Third Korea” are numbered. Even the infusion of South Korean money is not enough to reverse the unavoidable process of assimilation. Koreans are not subjected to forced Sinification; they are making a rational choice, even if it is one that Korean nationalists may not approve. If things continue as such, in a few decades only hanbok-clad girls and the obligatory signs in Korean shops and restaurants will remind one of the Korean community that once thrived in Yanbian. But I hope it will always be a good place to feast on dog meat.

Notes:

[1] For the views of nationalists see, for example, their site.

[2] Ch’ulipkuk kwanli yeonpo, 2006 (The Immigration Yearbook, 2006). Seoul, Minister for the Interior, 2007, p.467.

[3] Zhang Tianlu. Zhongguo shaoshu minzu renkou yanjiu (Research on the population of Chinese ethnic minorities).

[4] Kim Tu-seop. Yeonbyon chosonchok sahoe-eui ch’oekeun pyonhwa: sahoe inkuhakchok cheopkeun (Recent changes in the ethnic Korean community of Yanbian, a socio-demographic approach). Hankuk inkuhak, Vol. 26, #2, 2003, p. 141.

[5] Ibid. p. 133-134.

[6] Ibid. p. 134.

[7] Pak Kyong-nae. Chungkuk Yeonbyeon choseonchok-eui mokuko sayong silt’ae (The current state of use of the mother tongue among ethnic Koreans in Yanbian). Sahoe ono hak Vol.10, # 1, p. 119.

For additional articles on Yanbian and Koreans in China see:

Yonson Ahn, China and the Two Koreas Clash Over Mount Paekdu/Changbai: Memory Wars Threaten Regional Accommodation.

Outi Luova, Mobilizing Transnational Korean Linkages for Economic Development on China’s Frontier.