|

International Law, another weapon in the battle for the South China Sea |

Introduction: a moment to take stock of the ongoing legal battle

This summer, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PAC) held the first oral hearings in the case brought by the Philippines against China concerning the South China Sea. Before considering any substantive issues, the PAC has to decide whether it has jurisdiction to issue a ruling.1 Earlier, the closing weeks of 2014 had seen three significant developments, with Hanoi making a submission to the PAC, Beijing publishing a position paper (while not submitting it to the Court), and the United States issuing a position paper of its own. We can also mention the continued interest in the South China Sea by other countries, including India and Russia. Taken together, it means that the time may have arrived to take stock of the arbitration case, updating our previous summer of 2013 piece “Manila, Beijing, and UNCLOS: A Test Case?”.2 At stake is not only this arbitration case, or even the entire South China Sea, but the role of international law in contributing to peaceful solutions to territorial conflicts, specifically whether it can help accommodate changes in relative power without recourse to military conflict.

Beyond the Philippines and China: Vietnam Makes a Move

After constant speculation on whether Vietnam would join forces with the Philippines and seek an international ruling on the South China Sea, Hanoi finally decided to make a submission3 to the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PAC) without joining Manila as a co-plaintiff.4 In its submission, Vietnam asked the PAC to assert its jurisdiction, give “due regard” to the country’s rights and interests in the Spratlys and Paracels, as well as in her EEZ and continental shelf, and declare China’s nine-dash line “without legal basis”. Hanoi’s submission could be seen as a response to Beijing’s position paper5 of 7 December 2014, spelling out the Chinese position, but not submitting it to the PAC in the Hague concerning Manila’s request for arbitration under UNCLOS (the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea).6 At the time of writing, the court is still considering whether it has the authority to rule on the case. A third relevant development in the last days of 2014 was a study7 by the US State Department, released on 5 December. Once again, it is clear that the legal battle launched by Manila is being closely followed by all the capitals concerned. In October 2015 US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Russel said that should the PAC rule it had jurisdiction, both the Philippines and China should abide by its decision, adding that this was what the United States and the international community expected.8

From day one, China has rejected the Philippines’ resort to international arbitration, arguing that the country had opted out of compulsory arbitration on sovereignty issues and that the suit violates bilateral agreements to solve disputes by negotiation. These were among the main arguments in Beijing’s statement laying down its position, a paper whose release some observers believe indicates that China cannot ignore international legal proceedings despite the fact that it has not been submitted to the PAC. The reaction to China’s paper was not limited to the Philippines; it also seems to have finally prompted Hanoi’s decision to join the battle on its own terms. On 11 December 2014, Vietnamese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Le Hai Binh made the following remarks9 in answer to questions from the press:

“Once again, Viet Nam reiterates that Viet Nam has full historical evidence and legal foundation to reaffirm its sovereignty over the Hoang Sa [Paracel Islands] and Truong Sa [Spratly Islands] archipelagoes, as well as other legal rights and interests of Viet Nam in the East Sea [Biển Đông]. It is Vietnam’s consistent position to fully reject China’s claim over the Hoang Sa and Truong Sa archipelagoes and the adjacent waters, as well as China’s claiming of ‘historic rights’ to the waters, sea-bed and subsoil within the ‘dotted line’ unilaterally stated by China”. The spokesman also confirmed that Hanoi had “expressed its position to the Tribunal regarding this case, and requested the Tribunal to pay due attention to the legal rights and interests of Viet Nam”.

It should be noted that Hanoi did not join Manila as co-plaintiff in the case, choosing instead simply to lodge a statement with the Permanent Court of Arbitration. Some observers took this as indicative of a desire not to “alienate Beijing”,10 while at the same time defending the country’s position. Furthermore, an un-named “regional source” told the South China Morning Post11 that Vietnam’s action “is as much to protect Vietnamese interests vis-à-vis the Philippines as it is directed against China”, with another adding that “There is reportedly no consensus in the Vietnamese Politburo on this subject. This is probably as far as the Politburo is prepared to go”. The same HK newspaper also quoted Rodman Bundy, a lawyer who believes that Hanoi’s statement “should be ignored by the tribunal given that Vietnam has no standing in the arbitration”, adding that the move was “a cat-and-mouse game going on outside the strict procedure of the arbitration”. Australian Professor Carlyle Thayer also spoke to theSouth China Morning Post, saying that Vietnam’s move was a way for the country to put forward her interests, adding that this amounted to “a cheap way of getting into the back door without joining the Philippines’ case”. Gregory Poling, South East Asia analyst at Washington-based think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies, believes that Vietnam’s statement had the same goal as “the Chinese position”, namely to “ensure that the justices hearing the case consider the arguments contained in the document, but do so in a way that is less provocative than Vietnam actually joining”.12

On 12 December 2014 Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hong Lei responded to a media question on Hanoi’s move. After repeating Beijing’s mantra about China’s “indisputable sovereignty over the Nansha Islands and their adjacent waters” and the “indisputable fact that the Xisha Islands are an integral part of China’s territory”, he said that “China will by no means accept Vietnam’s illegal and invalid sovereignty claims over Nansha and Xisha Islands”. Hong called on Hanoi to “work with China to resolve relevant disputes over the Nansha Islands through consultation on the basis of respecting historical facts and international law so as to jointly safeguard peace and stability in the South China Sea”, insisting that Beijing would not take part in the arbitration proceedings for reasons previously explained in detail in the 7 December position paper, and that “China’s position will not change”.13

Hanoi’s decision to address the PAC may have been a compromise outcome directed not just at Beijing but also at Manila. The decision took place in parallel with high-level meetings with China and others in the South China Sea. Perhaps a good starting point to look at these contacts would be the trip to Beijing in August last year by Le Hong Anh, a special envoy of the Secretary General of the Vietnam Communist Party (VCP). As Carl Thayer notes, this “marked an important inflection point in Sino-Vietnamese relations following the HD 981 oil rig crisis of the preceding three months”.14 Anh met Xi Jinping, Liu Yunshan (secretary of the CCP Central Committee and a member of the Politburo Standing Committee), and Wang Jiarui (vice chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference). These meetings led to more concrete agreements, and in particular in the words of Vietnam’s Foreign Affairs Ministry “three important points”, namely enhanced “bilateral ties between parties and states, boosting sound and stabilised relations between the two countries”, promoting bilateral visits, and working to “restore and enhance bilateral relations in all fields” and to “seriously implement the agreement on the basic principles guiding the settlement of sea related issues between Viet Nam and China; to effectively implement government-level negotiations on Viet Nam-China borders and territory; to seek basic and long-term solutions acceptable to both sides; to effectively control sea disputes and not act to complicate or expand disputes; to maintain peace and stability in the East Sea; and to maintain overall Viet Nam-China relations”.15 Furthermore, the meetings led to “the resumption of bilateral contacts, high-level visits and a meeting of government leaders”. In addition to the 16-18 October Vietnamese senior military delegation’s trip to China, discussed below, State Councilor Yang Jiechi traveled “to Hanoi to co-host the 7th Joint Steering Committee meeting on October 27” plus the 10 November meeting, “on the sidelines of the APEC Summit in Beijing”, between Chinese President Xi Jinping and his Vietnamese counterpart.16

In December 2014, the first visit to Vietnam by a leading Chinese official that year took place. Yu Zhengsheng (chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference) traveled to the country, invited by the Communist Party of Vietnam Central Committee and the Fatherland Front of Vietnam. According to Xinhua, the trip was designed to “to further mend bilateral ties after recent tensions” and the May 2014 anti-Chinese riots. The report stressed the “common border, similar culture and high economic complementarity” with China, “Vietnam’s largest trade partner for nine years in a row, while Vietnam has become China’s second largest trade partner in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations”. The text concluded saying that “there is reason to believe that if the two nations, especially Vietnam, cast their eyes on improvement and development of relations instead of aggravating differences, benefits will not only be brought about to themselves but also to the whole region”.17 This is in line with many Chinese injunctions to neighbors to work together to improve relations, while not offering any concrete solution to the territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Reporting on Yu’s meeting with Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung in Hanoi on 26 December, Xinhua chose the headline “China, Vietnam agree to properly settle maritime disputes”.18 Here the word “properly” may perhaps be a thinly-disguised criticism of international arbitration and other dispute resolution mechanisms not to Beijing’s liking. Yu described the maritime issue as “highly complicated and sensitive, which requires negotiations to manage and control differences”, adding “Megaphone diplomacy can only trigger volatility of public opinion, which should be avoided by both sides”. 19

Commenting on the succession of high-level meetings, last year, and in particular the succession of two joint Steering Committee for Bilateral Relations meetings just a few months apart (in June and October), Thayer pointed out that this was “an indication that China’s top leaders are willing to engage with Vietnam to reset their bilateral relations, which were severely strained by the oil rig crisis”.20 After some rumors,21 it was confirmed that Vietnamese Communist Party leader Nguyen Phu Trong would be visiting China in early April.22

At a lower level, but providing opportunities for discussion, was the 65 anniversary of Sino-Vietnamese diplomatic relations in January,23 where both countries’ friendship association heads stressed their wish for closer relations, chairman of the Viet Nam Union of Friendship Associations Vu Xuan Hong saying “it’s necessary to have more friendly exchanges between Vietnam and China to improve trust and narrow differences. Let’s work for more appropriate cooperative measures for mutual benefit and implement an action program for the Vietnam-China strategic partnership”.24

In addition, Vietnam and China regularly hold bilateral cooperation meetings on a number of issues, including the fight against drug trafficking.2526.27

In the military sphere, the last days of 2014 brought news that “the Chinese and Vietnamese navies will continue their joint patrol in the Beibu Gulf in 2015 to safeguard its security and stability”.28 Earlier in October 2014, following an “unexpected three-day visit to Beijing by a 13-member high-level Vietnamese military delegation from October 16-18, led by Minister of National Defense General Phung Quang Thanh” the two Defense Ministries agreed to set up a direct hot line. According to Thayer, “This is an indication that both sides realized how quickly an incident could spiral out of control and lead to deadly force”. He also noted that “From Vietnam’s point of view, it was important to demonstrate domestic political unity by bringing such a large delegation to Beijing”, 2”.29

In short, both China and Vietnam have engaged in major efforts to prevent tensions from getting out of hand. Yet no progress is apparent in the ultimate factor fanning the flames, that is the maritime territorial dispute between the two countries. Some observers have noted that Hanoi may be split on how to deal with China, and more generally the direction of the country’s foreign policy and military alliances. While this seems to be the case, we should be careful not to confuse disputes on how to manage a complex set of relations in search for balance and a maximization of national power, with disputes over ultimate goals. It is more likely that Vietnamese leaders are split on how to deal with China, and other countries such as Russia, the US, and India, rather than on the ultimate goal of embracing a wide range of alliances in order to prevent falling prey to a bigger neighbor. This is a traditional pillar of the country’s foreign policy, hence Vietnam seeks to develop bilateral relations with a wide range of actors, playing one off against the other when necessary, including China and India.30 Stephen Blank notes that “Vietnam not only enjoys strong U.S., Russian, and Indian diplomatic and military support, it is buying weapons from Russia, Sweden, and Israel, among others”.31 To this we must add active participation in a large number of international organizations. At a conference in August, Prime Minister Dung described the country’s foreign policy as resting on “independence, self-reliance, multilateralism, diversification, and international integration”.32

In addition to the already noted lack of substance in many Sino-Vietnamese statements, it is not clear to what extent either side has margin for compromise. Many voices in both China and Vietnam stand ready to criticize their respective governments for any perceived softening and betrayal of the national interest. For example, in August 2014, in the wake of the announcement of a trip to China by Politburo member Le Hong Anh, Nguyen Trong Vinh (former Vietnamese ambassador to China) said “China will never compromise. Their removal of the oil rig was only temporary. They will never abandon their wicked ambitions of taking a monopoly over the East Sea”, while Nguyen Quang A (an economist opposed to the government) “said he welcomed the talks but was concerned that Beijing might be trying to persuade Hanoi to drop its threat of taking international legal action against China’s territorial claims”.33 Vietnamese dissenters often attack Hanoi for the alleged failure to stand up to Beijing, while not a few Chinese netizens voice strong criticisms on foreign policy. There seems to be a recognition in leadership circles on both sides that domestic public opinion, if unchecked, may prove destabilizing, restricting room for maneuver. As freelance journalist Roberto Tofani noted in 2013 “Beijing and Hanoi must now also face rising nationalism among their citizens, including periodic anti-China street protests in Vietnam and widespread anti-Vietnam rhetoric on Chinese citizens’ private blogs and Facebook pages related to the South China Sea disputes”.34

In support of Vietnamese claims in the South China Sea, Hanoi has often employed French maps and French documentation to emphasize continuity of territorial boundaries from the colonial to the post-colonial era. Vietnamese observers have stressed the need to examine historical evidence, in a wide sense of the term, to counter similar efforts by Beijing, in a view also supported by some experts in other countries. For example, following Bill Hayton’s “The Paracels: Historical evidence must be examined” and subsequent response by Li Dexia and Tan Keng Tat (“South China Sea disputes: China has evidence of historical claims”)35, Vietnam’s Nguyen Hong Thao wrote in support of Hayton, arguing that Chinese “evidences should not be accepted without debating and examining”, and defending the view that Song Dynasty maps “unanimously described Hainan island as the Southern terminus of China”.36

Nguyen Hong Thao refers to the 13thcentury Song Dynasty Chinese book “Chu Fan Chi / Zhu Fan Zhi” (Notes for Foreigners or Records of Foreign Peoples) by Chao Ju-kuo (Zhao Ju Guo). He rejects Chinese claims that the book proves that the Paracels were part of China’s territory at the time, noting that “‘Chu Fan Chi’ was about ‘vassal kingdoms’ or ‘barbarous tribes’ … Consequently, it is obvious that the lands recorded in this book were not Chinese”. While the original text of the book has been lost, some commentators, writing in other contexts, such as China’s contacts with Africa, have noted that it addressed what were considered foreign lands.37

Like their Chinese counterparts, Vietnamese authors use public displays of maps and documents as another weapon in this struggle. For example in September 2015 one such exhibition took place in Da Lat city, with the goal of proving Vietnamese sovereignty over the Hoang Sa (Paracel) and Truong Sa (Spratly) archipelagos and featuring “UNESCO-recognized woodblocks from the Nguyen Dynasty, bibliographies and atlas collections published by many countries in different times, notably an atlas issued by China’s Qing dynasty in 1906 and subsequently used by the Republic of China”, as well as documents from different Vietnamese dynasties, the Republic of Vietnam, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, and Western countries.38

Vietnam relies on two kinds of Western sources. On the one hand, records of missionaries and traders, and, as noted, on official documents from the French colonial administration and other powers.

Duy Chien, in a 2014 article draws on the writings of foreign missionaries and navigators.39 For example, a French missionary traveling to China onboard the ship Amphitrite wrote in a 1701 diary: “Paracel is an archipelago belonging to the Kingdom of Annam. It’s a terrible submerged reef, stretching hundreds of miles.”40 More directly related to sovereignty, or at least to sovereignty claims, are “Notes on the geography of Southern Vietnam”, by Priest Jean-Louis Taberd (former apostolic vicar of Cochinchina from 1824 to his death in 184041 and interpreter of King Gia Long). Published in 1837, the Notes describe the 1816 flag-raising ceremony on the Paracels by King Gia Long: “Paracel or Hoang Sa islands is an area crisscrossed by small islands, reefs and sand, seems to be extended to 110 North latitude and around 1070 longitude… Although this is an archipelago covered by nothing else but islands and reefs, and the depth of the sea promises [more] inconveniences than advantages, King Gia Long still thought that he had the right to expand his territory by that pathetic merger. In 1816, the King held a solemn flag hoisting ceremony and formally took possession of the reefs, with a certain belief that no one would struggle with him…” J.B. Chaigneau also mentions the 1816 ceremony.42

The Nguyen Dynasty’s exercise of tax powers over foreign ships passing through the Hoang Sa (Paracels) area is perhaps among the strongest pieces of historical evidence that the Vietnamese advance, reinforced by the fact that it was recorded in non-Vietnamese sources. Thus Gutzlaff, a member of the Royal Geographic Society of London, in 1849 wrote in the Society’s Journal that “Katvang lies 15 – 20 nautical miles from Annam coast and spreads on 15 – 17 degrees north latitude, 111 – 113 longitude, then the King of Annam claims ownership of these islands, including rocks and reefs dangerous to marine navigation… Annam government benefits from setting up a patrol boat and a small garrison to collect taxes and protect fishermen operating in their water…”. This source is interesting because Gutzlaff acknowledges both a long-standing presence by Chinese fishermen in the area, as often insisted on by Beijing, and the exercise of state power by the Vietnamese in the region: “From time immemorial, junks coming largely from Hainan have annually visited all these shoals, and proceeded in their excursions as far as the coast of Borneo. ”.

The white paper published by the Republic of Vietnam in 1975 insisted on the actions described in French sources,43and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam has followed the same line. Furthermore, Hanoi has been keen to emphasize that French domination over Indochina not only did not interrupt the exercise of sovereign powers but actually reinforced it, since the new authorities kept exercising sovereign rights “After France and Vietnam had signed the Protectorate Treaties of March 15, 1874 and June 6, 1884”, including “building and operating lighthouses and meteorological stations, establishing administrative delegations responsible for the archipelago attached to Thua Thien Province (Annam), and granting birth certificates to Vietnamese citizens born in the archipelago”. France went as far as requesting that China solve the dispute by international arbitration (French Note Verbale dated February 18, 1937 addressed to China), but the proposal was refused. Paris also protested in 1947 after the Republic of China occupied the year before Phu Lam (Woody) Island, in the Paracels, and although a request for negotiations and third-party adjudication was refused, ROC forces later withdrew.44”. Having said this, some Vietnamese accounts of the colonial years complain that French authorities were too passive in light of Chinese, and later Japanese, attempts to encroach on islands considered to be Vietnamese, and explain how it was only after such attitude was denounced in the press that they firmed it up. From 1931 to 1933 journalist Cucherousset published seven articles in L’Éveil Économique de L’Indochine (issues 685, 688, 743, 744, 746, 777 and 790) criticizing Governor Pasquier for his feeble defense of sovereignty over Hoang Sa. He wrote “Annam’s sovereignty over the Paracel Islands is undeniable”, while asking the governor “Which obstacles have prevented Annam from claiming sovereignty over the Paracel Islands, which they have owned for hundreds of years? Do we have to wait until the Japanese exploit the last tons of phosphate? Or is it true that the Japanese have paid a reasonable commission?”. Many other newspapers, both in metropolitan France and Indochina (the latter in both French and Vietnamese), regularly reported on the disputed islands, listing the grounds to oppose Chinese and Japanese designs.45

Vietnam’s South China Sea narrative also relies on international treaties signed by Paris, such as the 1887 Conventionon the land border, signed by France and theQing dynasty, and according to which islands located east of a red line (described on a map attached to the treaty) belonged to China. Duy Chien argues that “This red line described on the map attached to the Convention was only 5 kilometers long, compatible with the width of the territorial waters of 3 nautical miles at that time, and functioned to demarcate the onshore islands within Tonkin Gulf. If following the [Chinese] authors’ interpretation, this line could be extended boundlessly, crossing the Tonkin Gulf, and not only Paracels and Spratlys but also Hue, Da Nang and even all the islands along the Central Coast of Vietnam or Con Dao island, also belonged to China consequently”. 46

Concerning the 1943 Cairo Declaration, Vietnam’s position is that it did not imply any transfer of disputed islands or other features in the South China Sea to China, stressing that “no mention was made of Truong Sa (Spratly Islands) and Hoang Sa (Paracel Islands)” and that the Republic of China “a party to the Conference …did not have any reserve or any statement of its own on the restored territories”.47

As is clear in a recent documentary by Ho Chi Minh City TV, Vietnam sees the East Sea, including the recovery of lost islands and features, as a matter of “vital space” (không gian sinh tồn) and “struggle for existence” (tranh đấu sinh tồn), expressions that appear often in the script. Commenting on the documentary, François Guillemot notes that “the documentary film prioritizes the history of the Paracels (Hoang Sa), the Vietnamese islets lost in 1974, while people are aware that China had effective control of that territory after that date”, concluding that “Vietnam has put its ‘struggle for existence’ in a long-term perspective, which, in the past, has shown a certain efficacy”.48

The Malaysian angle: Manila tempts Kuala Lumpur with a downgrade of its Sabah claims

Another Filipino move connected to the international arbitration case is the offer to Malaysia, in a Note Verbale, to review its protest against the 6 May 2009 joint Vietnamese-Malaysian submission to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), containing a claim by Kuala Lumpur of an extended continental shelf (350 nautical miles from the baselines) projected from Sabah. In exchange for this, Manila is requesting two actions that it believes would reinforce her case against China: First, to “confirm” that the Malay claim of an extended continental shelf is “entirely from the mainland coast of Malaysia, and not from any of the maritime features in the Spratly islands”. Second, to confirm that Malaysia “does not claim entitlement to maritime areas beyond 12 nautical miles from any of the maritime features in the Spratly islands it claims”. According to former Philippine permanent representative to the United Nations Lauro Baja Jr., if Malaysia accepts the deal, the Philippines’ claim to Sabah will be “prejudiced”, adding “We are in effect withdrawing our objection to Malaysia’s claim of ownership to Sabah”.49

Manila’s proposal is important for several reasons. First, because it illustrates how the Philippines is trying to involve as many countries as possible in its attempt to have the 9-dash line declared to be incompatible with international law. Second, because in so doing it is ready to compromise one of their own territorial claims, thus showing they are aware that they may have to sacrifice some of their long-standing policies in order to arrest what they consider to be the main threat to their territorial integrity. Third, given Malaysia’s reluctance to follow the road suggested by the Philippines, this confirms the fact that South China Sea coastal states remain reluctant to openly coordinate to oppose Chinese claims. Finally, by appearing ready to drop or at least downgrade claims to Sabah, Manila is showing that it is more confident in UNCLOS than in historical claims when it comes to defending its territorial claims over the Spratlys. The reason is that, while Manila’s claims are understood to be grounded in post-WWII developments, an alternative route for the Philippines would be to say that the features involved used to be part of the Sultanate of Sulu even before the Spanish conquest, a route which would demand that Manila not only retains but reinforces the claim to Sabah.

|

LNG flows, one of the many reasons why the South China Sea is widely considered to be strategic |

Rearmament and widening alliances: the background to Manila’s arbitration bid.

Manila’s legal bid to cut short China’s maritime expansion is part of a wider strategy involving rearmament (among others, purchasing FA-50 light fighters from South Korea)50 and closer defense links with the US and regional powers like Japan and Vietnam. In the case of relations with Washington, the impact of rising tensions in the South China Sea is twofold and seemingly to some extent contradictory. On the one hand, the Philippines and the United States have grown tighter, while on the other Manila has diversified and widened her alliances, no longer relying almost exclusively on Washington. Although this parallel reinforcement and diversification may not be without its contradictions in the future, for the time being it seems to be fitting reasonably well with the US dual Pacific policy of reengagement and increasing reliance on regional allies for military support. We could also note that the need to upgrade external defense and invest more in the air force and the navy may have provided Manila with an additional reason to be flexible in continuing the long and difficult path toward a peaceful settlement with Muslim rebels in the country’s south. While there are many other reasons to wish the peace process in Mindanao to conclude successfully, friction in the South China Sea is clearly one, and this has not been lost on regional allies like Japan, which retains a discrete but clear interest in developments in the island.

Similarly, Hanoi’s decision to join the international arbitration case should not be seen in isolation, but rather as part of a multi-faceted strategy which like Manila’s also involves rearming and developing closer ties to other countries, including Japan (which is providing patrol boats to her coastguard), India (a key partner in developing offshore oil and also a patrol boat supplier),51 Russia (essential weapons supplier and energy industry partner), and the United States (whose Pacific Fleet commander visited Vietnam in December 2014).52

Concerning bilateral relations between Vietnam and the Philippines, their respective territorial claims are to some extent overlapping, hence the two countries are not completely at one. However, there is some evidence for tighter links, not least of which the port visit in November 2014 by two Russian-built Vietnamese frigates to Manila, the country’s first ever.53 The 29-30 January 2015 trip to the Philippines by Viet Nam’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs Pham Binh Minh inaugurated “discussions towards the establishment of a Strategic Partnership and its elements with a view to elevating the level and intensity of bilateral exchanges between the two countries”. According to the Philippines’ Government, concerning the South China Sea, Minh and Secretary of Foreign Affairs Albert F. del Rosario “agreed that concerned Parties should adhere to the ASEAN-China Declaration of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) and soon conclude a Code of Conduct (COC)” and “reaffirmed their commitments to a peaceful resolution of disputes in the SCS in accordance with international law and the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)”.54 Commenting on this trip, Carl Thayer wrote that it was “likely that a formal strategic partnership agreement could be reached this year”, adding that negotiations constitute “a determined diplomatic effort to shore up Vietnam’s relations with fellow members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)”, and underlining that “Growing Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea in recent years has led to a growing convergence of strategic interests between Manila and Hanoi”. Concerning the meaning of the term “strategic partnership agreement”, he cautions that “Both sides, however, want to broaden cooperation in order to avoid the appearance that the strategic partnership is a military pact by another name”, adding that existing trade and investment links are weak.55 In more concrete terms, he mentions that “Vietnam could seek to leverage off the recently inaugurated U.S. Poseidon surveillance flights from the Philippines, for example”.56 As noted by Del Rosario, this would be the third such agreement for Manila, following similar deals with Tokyo and Washington.

There are many obstacles to meaningful cooperation between the Philippines and Vietnam, going beyond generic statements of support for the rule of law at sea. They include poor interoperability and a weak record of past military cooperation. However, there is a growing realization in both Hanoi and Manila that closer links may allow them to reinforce the credibility of their defense posture, and more widely, their diplomatic stance concerning the South China Sea. ASEAN may seem the perfect forum for this closer cooperation to take place at the political level, while better interoperability would demand the regular holding of drills and exchanges, bilaterally or within a wider framework probably including the United States and Japan. This regional cooperation could perhaps take the place of joint air patrols.57 In order to avoid being seen as squarely confronting China, such joint air patrols may focus on search and rescue, and environmental monitoring. The interoperability and joint operational experience gained, however, could then be applied to other scenarios.

Beijing puts forward its own views of the conflict

Post-Mao China has followed a somewhat contradictory approach to international law. To a large extent, this mirrors the country’s complex domestic relationship with the concept of the rule of law. On the one hand, China’s reopening of her law schools after the Cultural Revolution and huge expansion of the legal profession and the practical, day to day, presence of the law, has led to a similar move in the international arena. However, this greatly expanded role of the law both domestically and internationally has been accompanied, in the internal domain, by a persistent rejection of the concept of “rule of law”, authorities rather leaning towards “rule by law”. In Chinese foreign relations, international law has had to contend with two obstacles. First, there is a mistrust of international tribunals, and the fear that they may impinge on Chinese sovereignty. Moreover, the South China Sea has been defined as a “core national interest”58, although the exact meaning of this term may not be completely clear .59 Second, with the notion that public international law is a creature of the Western nations and thus inextricably linked to a historical period of foreign domination that only began to be reversed after the 1949 Communist victory.60 This applies particularly to the law of the sea, seen as unfairly constraining the legitimate aspirations of a nation that has grown increasingly dependent on maritime trade and which feels surrounded by a chain of islands in hostile hands.

Throughout the international arbitration saga, China has repeatedly proclaimed that it would not accept the court’s jurisdiction. However, China has finally deemed it necessary to issue a formal document stating her posture. Some see this as a simple restatement of China’s position, confirming that it will not take part in the proceedings. Others see it as a small victory for the Philippines and international arbitration, since China has not been able to stay completely aloof from the case. Regardless, it is usefull to examine the document,61 dated 7 December 2014, some of whose main points are summarized here, noting in brackets the paragraph quoted or commented on. A more detailed analysis of Beijing’s response can be found in Appendix I to this paper.

The paper opens making it clear that issuing it is not equivalent to taking part in the arbitral proceedings, and then lists (Paragraph 3) its main purposes, each covered in one section, numbered from II to V.

These goals are first of all (Section II, Paragraphs 4-29) to stress that the case concerns “the territorial sovereignty over several maritime features in the South China Sea”, which, contrary to Filipino assertions, “is beyond the scope of the Convention and does not concern the interpretation or application of the Convention”. Next (Section III, Paragraphs 30-56), to explain that “China and the Philippines have agreed, through bilateral instruments and the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, to settle their relevant disputes through negotiations” and the arbitration proceedings are thus a breach by Manila of “its obligation under international law”. Third (Section IV, Paragraphs 57-75), “assuming, arguendo, that the subject-matter of the arbitration” was interpreting or applying UNCLOS, the paper argues that it would still be “an integral part of maritime delimitation” thus falling squarely within China’s derogation from compulsory arbitration. Fourth (Section V, Paragraphs 76-85), the text underlines that, in Beijing’s view, “the Arbitral Tribunal manifestly has no jurisdiction over the present arbitration” and defends the view that China’s refusal to take part in the proceedings stands “on solid ground in international law”.

In Section II, the document (5) sums up the different Filipino constitutional and legal provisions defining her national territory, including references to “all the territory ceded to the United States by the Treaty of Paris concluded between the United States and Spain” in Article 1 of the 1935 Constitution. This is interesting because it implicitly contradicts Washington’s claim to take no sides in territorial disputes in the South China Sea, stressing only peaceful resolution in accordance with international law. The problem with this posture, in the case of the Philippines, is that, given that they were under American sovereignty, by saying it does not take any position on sovereignty the US is saying that it does not know the extent of its past territory. Therefore, we might ask what Beijing’s motivation in bringing up such treaties may be. At first glance it would seem better for China if the US sticks to this policy of not commenting on territorial claims themselves. On the other hand, however, Beijing may perhaps hope to prompt Washington to publicly comment on the matter in a way that may be detrimental to Manila, that is by stating that certain features claimed by the Philippines were not under US sovereignty in the past.

Taiwan and the “One-China Principle” are not absent from China’s document either, the text (22) accusing Manila of committing a “grave violation” of the principle for omitting Taiping Dao (Island) from the list of “maritime features” described as “occupied or controlled by China”. Instead, the text describes it as being “currently controlled by the Taiwan authorities of China”. A reminder that the conflict over the South China Sea is connected with that over Taiwan, in a number of ways. We may ask ourselves whether Manila was departing here from her “One-China Policy”. Was this a warning shot, or merely another example of how state practice concerning Taiwan is moving (sometimes inadvertently) away from Beijing’s strict position in many countries.62

Section 28 stresses that “China always respects the freedom of navigation and overflight enjoyed by all States in the South China Sea in accordance with international law”. While this is in line with repeated assertions by Chinese authorities, it prompts further doubts on the exact nature of Beijing’s claims, for if all China was demanding was an EEZ then freedom of navigation and overflight would simply flow from international law, without the need for any concession by the coastal state. The issue is made more complex by the fact that in Beijing’s view the rights of coastal states are more extensive than in the eyes of countries such as the United States, going as far as including the right to authorize or deny military activities such as electronic intelligence gathering, which has been the source of a number of incidents, some of them fatal. Thus, if what China is claiming is an EEZ, is Beijing making a concession and accepting a lesser set of coastal state rights in the particular case of the South China Sea? Alternatively, should we read “freedom of navigation and overflight” as being restricted to civilian ships and planes, or at least not including any activities such as ELINT (electronic intelligence) gathering that might be prejudicial to the coastal state? Other questions may be prompted by China’s assertion. For example, does this also apply to territorial waters around Chinese islands in the South China Sea? A question made more complex by the fact that there is no agreement over which islands are legally recognized as islands given the extensive reclamation work taking place.

In Section III Beijing provides a long list of bilateral agreements and statements, and ASEAN documents, stipulating commitments to settle disputes by negotiation and agreement, in order to prove Manila is therefore “debarred from unilaterally initiating compulsory arbitration”. With regard to the absence of an explicit exclusion of third-party settlement, which as pointed out the text acknowledges, China cites the “Southern Bluefin Tuna Case”,63 where the arbitration tribunal stated that “the absence of an express exclusion of any procedure … is not decisive”, that is the fact that a treaty commits parties to negotiate rather than resort to other, non-consensual, dispute settlement techniques prevents the latter from coming into play, without the need to specifically list all the possibilities. In that case, the applicable treaty required the parties to “consult among themselves with a view to having the dispute resolved by negotiation, inquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement or other peaceful means of their own choice”, and the ICJ determined that “That express obligation equally imports, in the Tribunal’s view, that the intent of Article 16 is to remove proceedings under that Article from the reach of the compulsory procedures of section 2 of Part XV of UNCLOS, that is, to exclude the application to a specific dispute of any procedure of dispute resolution that is not accepted by all parties to the dispute.” For China, bilateral agreements and statements with the Philippines and the DOC are not separate realities, but (39) “mutually” reinforce “and form an agreement between China and the Philippines”, giving rise to “a mutual obligation to settle their relevant disputes through negotiations”. Beijing is very keen to insist not only that it prefers bilateral (as opposed to multilateral, or arbitration) dealings, but that Manila has agreed to this.

We can thus see how the document, despite stressing that it is not a formal reply, systematically rejects all of Manila’s arguments, while summarizing China’s position. While China emphasizes the Philippines’ alleged commitment to deal with the issue bilaterally, the text refers to treaties between the country’s former colonial masters, and touches upon the sensitive issue of Taiwan. It is a reminder of how difficult it is to keep things bilateral in this corner of the world.

US Interpretations of China’s 9-Dash Line

Despite repeatedly stating that it will not take sides in territorial disputes in East Asia, Washington remains keenly interested in the ultimate fate of the South China Sea. In addition to perennial calls to settle disputes peacefully, regular reminders of the importance of freedom of navigation, military aid to regional actors like the Philippines, and support for a more active policy by non-littoral maritime democracies like India and Japan, the US Department of State took a further step late last year by issuing a document64, part of its “Limits in the Seas” series. The text seeks to explain the different ways in which one may interpret Chinese maritime claims in the South China Sea (“that the dashes are (1) lines within which China claims sovereignty over the islands, along with the maritime zones those islands would generate under the LOS Convention; (2) national boundary lines; or (3) the limits of so-called historic maritime claims of varying types”). It concludes that the “dashed-line claim does not accord with the international law of the sea” unless “China clarifies that” it “reflects only a claim to islands within that line and any maritime zones”. The text explains that it includes supporting Chinese official views, without attributing “to China the views of analysis of non-government sources, such as legal or other Chinese academics”.65 Concerning this latter restriction, although it is of course official sources which may be considered to be most authoritative when it comes to interpreting a government’s position, we should not forget that administrations in different countries will often resort to “two-track diplomacy” or employ semi or non-official back channels to test the waters and lay the groundwork for future formal negotiations.

|

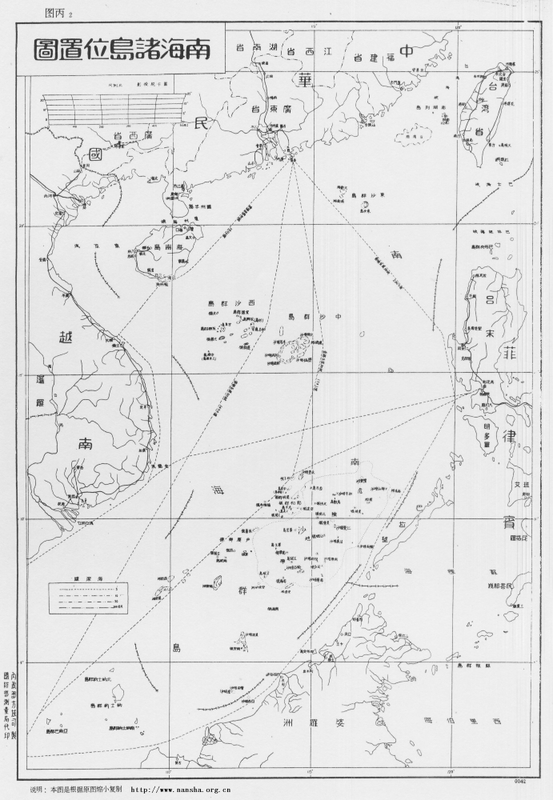

Nine-dash map attached to China’s two 2009 Notes Verbales |

We should note that the American policy of not taking sides concerning the ultimate issue of sovereignty could be challenged given Washington’s past sovereignty over the Philippine Archipelago. While this has not been publicly stressed by Manila to date, it could enter the debate as a means of putting more pressure on Washington to adopt a more robust posture.

The 7 December 2014 paper by the Department of Statebegins by stressing that “China has not clarified through legislation, proclamation, or other official statements the legal basis or nature of its claim associated with the dashed-line map”, explains the “origins and evolution” of the dashed-line maps, provides a summary of the different maritime zones recognized and regulated by UNCLOS, and then proceeds to explain and discuss three possible interpretations of that claim “and the extent to which those interpretations are consistent with the international law of the sea”.66 The document contains a number of maps, including (Map 1) that was referred to in China’s two May 2009 notes verbales to the UN Secretary General,67 which stated that “China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof . The above position is consistently held by the Chinese government, and is widely known by the international community”.68

The text first outlines the history of China’s maps of the South China Sea containing dashed lines, starting with a 1947 map published by the Nationalist government, noting that later PRC maps “appear to follow the old maps”69 with two significant changes: the removal of two dashes inside the Gulf of Tonkin (in an area partly delimited by Vietnam and the PRC in 2000) and the addition of a tenth dash to the East of Taiwan.70 These two changes can be interpreted in different ways, to some degree contradictory. On the one hand, the partial delimitation agreement with Vietnam could be seen as evidence of Chinese pragmatism and flexibility, and proof that it is possible for countries in the region to at least partly settle their disputes by diplomacy. On the other, explicitly encompassing Taiwan with an extra dash may be seen as a reinforcement of Chinese claims on the island not necessarily based on the will of her population. Alternatively, it could simply be a way to more comprehensively encompass the waters and features that Beijing (either directly or via Taipei) wishes to master.

The paper then examines successive Chinese maps from a cartographic perspective, stressing that “China has not published geographic coordinates specifying the location of the dashes. Therefore, all calculations in this study relating to the dashed line are approximate”. This same criticism has been made of the San Francisco Treaty.71This section of the paper stresses that “Nothing in this study is intended to take a definitive position regarding which features in the South China Sea are ‘islands’ under Article 121 of the LOS Convention or whether any such islands are ‘rocks’ under Article 121(3)”. This is in line with Washington’s refusal to take sides concerning the ultimate sovereignty disputes in the region. The text notes that the “dashes are located in relatively close proximity to the mainland coasts and coastal islands of the littoral States surrounding the South China Sea”, and explains that, for example, Dash 4 is 24 nm from Borneo’s coast, part of Malaysia. Generally speaking, “the dashes are generally closer to the surrounding coasts of neighboring States than they are to the closest islands within the South China Sea”, and as explained later this is significant when it comes to interpreting the possible meaning of China’s dashed line, since one of the principles of the Law of the Sea is that land dominates the sea, and thus maritime boundaries tend as a general rule to be equidistant. That is, maritime boundaries tend to be roughly half way between two shores belonging to different states. To hammer home this point, the study includes a set of six maps (Map 4) illustrating this. The report criticizes the technical quality of the PRC maps, saying that they are inconsistent, thus making it “complicated” to describe the dashed line, whose dashes are depicted in different maps “in varying sizes and locations”. Again, this is important in light of possible interpretations of Chinese claims, since this lack of consistency and quality not only obfuscates Chinese claims, introducing an additional measure of ambiguity, but also makes it more difficult to ascertain whether historical claims are being made and whether they are acceptable in light of international law. .72

The paper’s second section basically consists of a summary explanation of “Maritime Zones”, “Maritime Boundaries”, and “’Historic’ Bays and Title” according to UNCLOS. Three aspects are of particular significance. First of all, that the interpretation provided is not necessarily that considered correct by China. Although this is not always squarely addressed, when discussing whether Chinese claims in the South China Sea are or are not in accordance with international law we should first define international law, and there is the possibility that as China returns to a position of preeminence she may interpret some of its key provisions in a different way. Second, as the paper itself notes, while China ratified UNCLOS in 1996, the United States has not, although she “considers the substantive provisions of the LOS Convention cited in this study to reflect customary international law, as do international courts and tribunals”. Not all voices take such a straightforward view of Washington’s failure to ratify the convention while claiming that it is mostly a restatement of customary law and therefore applicable anyway.73 Some critical observers see the United States as being, together with Japan, among the largest beneficiaries of UNCLOS, in addition to being the driving force behind it, even while refusing to ratify a convention from which China has gained almost nothing.

Third, the page devoted to “’Historic’ Bays and Title”. The text stresses that “The burden of establishing the existence of a historic bay or historic title is on the claimant”, adding that the US position is that in order to do this the country in question must “demonstrate (1) open, notorious, and effective exercise of authority over the body of water in question; (2) continuous exercise of that authority; and (3) acquiescence by foreign States in the exercise of that authority”.74 The text explains that this traditional American perspective is in line with the International Court of Justice75 and “the 1962 study on the ‘Juridical Regime of Historic Waters, Including Historic Bays,’ commissioned by the Conference that adopted the 1958 Geneva Conventions on the law of the sea”.76 It then turns its attention to the regulation of historic claims in Articles 10 and 15 of UNCLOS,77 saying that they are “strictly limited geographically and substantively” and apply “only with respect to bays and similar near-shore coastal configurations, not in areas of EEZ, continental shelf, or high seas”.78 Just like, when examining China’s posture we must take into account, as discussed later, the country’s history, and in particular the Opium Wars and their aftermath, American history has also shaped Washington’s perceptions and principles. The Barbary Wars79 were widely seen as laying down fundamental principles of national policy such as rejection of blackmail, freedom of navigation, and the right and duty to intervene far from American shores whenever the country’s interests, principles, and prestige were at stake.80 Thus, while China’s position concerning the South China Sea may end up resting at least in part, on the concept of historic waters, even if this is not the case history and perceptions of history will surely still play an important role in determining Beijing’s policy. This, however, is not something only taking place within China, since no regional or extra-regional actor is immune to the phenomenon, adding to the already tense situation in South East Asia. In particular, a couple of centuries later, both the Barbary Wars and the Opium Wars remain powerful factors projecting their shadow on American and Chinese foreign and defense policy.

Let us move to the three interpretations put forward by the US Department of State.

1.- “Dashed Line as Claim to Islands”81

This would mean that all Beijing was claiming were the islands within the dashed lines, and that any resulting maritime spaces would be restricted to those recognized under UNCLOS and arising from Chinese sovereignty over these islands.

As possible evidence for this interpretation, the study cites some Chinese legislation, cartography, and statements. The former includes Article 2 of the 1992 territorial sea law, which claims a 12-nm territorial sea belt around the “Dongsha [Pratas] Islands, Xisha [Paracel] Islands, Nansha (Spratly) Islands and other islands that belong to the People’s Republic of China”.82 The Department of State also stresses that China’s 2011 Note Verbale states that “China’s Nansha Islands is fully entitled to Territorial Sea, Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and Continental Shelf”,83 without laying down any other maritime claim. Concerning cartography, the study cites as an example the title of “the original 1930s dashed-line map, on which subsequent dashed-line maps were based”, which reads, “Map of the Chinese Islands in the South China Sea” (emphasis in the DOS study). With regard to Chinese statements, the study cites the country’s 1958 declaration on her territorial sea, which reads “and all other islands belonging to China which are separated from the mainland and its coastal islands by the high seas”84 (emphasis in the DOS study). The text argues that this reference to “high seas” means that China could not be claiming the entirety of the South China Sea, since should that have been the case there would have been no international waters between the Chinese mainland and her different islands in the region. This is a conclusion with which it is difficult to disagree, although we should not forget that it was 1958, with China having barely more than a coastal force rather than the present growing navy. Therefore, while the study’s conclusion seems correct, and precedent is indeed important in international law, it is also common to see countries change their stance as their relative power and capabilities evolve. Thus, if China had declared the whole of the South China Sea to be her national territory in 1958 this would have amounted to little more than wishful thinking, given among others the soon to be expanded US naval presence in the region and extensive basing arrangements. Now, 50 years later, with China developing a blue water navy, and the regional balance of power having evolved despite the US retaining a significant presence, Beijing can harbor greater ambitions.85

2.- “Dashed Line as a National Boundary”86

This would mean that Beijing’s intention with the dashed line was to “indicate a national boundary between China and neighboring States”. As supporting evidence for this interpretation, the DOS report explains that “modern Chinese maps and atlases use a boundary symbol to depict the dashed line in the South China Sea”, adding that “the symbology on Chinese maps for land boundaries is the same as the symbology used for the dashes”. Map legends translate boundary symbols as “either ‘national boundary’ or ‘international boundary’ (国界, romanized as guojie)”. Chinese maps also employ “another boundary symbol, which is translated as ‘undefined’ national or international boundary (未定国界, weiding guojie)” but this is never employed for the dashed line.

The report stresses that, under international law, maritime boundaries must be laid down “by agreement (or judicial decision) between neighboring States”, unilateral determination not being acceptable. The text also notes that the “dashes also lack other important hallmarks of a maritime boundary, such as a published list of geographic coordinates and a continuous, unbroken line that separates the maritime space of two countries”. The latter is indeed a noteworthy point, since border lines would indeed seem to need to be continuous by their very nature, rather than just be made up of a number of dashes. This is one of the aspects making it difficult to fit Beijing’s claims with existing categories in the law of the sea. Moving beyond the law, however, and this is something that the DOS report does not address, a certain degree of ambiguity may be seen as beneficial by a state seeking to gradually secure a given maritime territory. Some voices have noted this may have been the US calculus in the San Francisco Treaty. Thus, the technical faults, from an international legal perspective, in China’s dotted line are not necessarily an obstacle to Beijing’s claims, from a practical perspective.

3.- “Dashed Line as a Historic Claim”87

The third way to see the dashed-line, according to the Limits in the Seas series paper, would be as a historic claim.

Concerning evidence for the possible interpretation of Beijing’s claims as historic, the report cites as “most notable” China’s “1998 EEZ and continental shelf law88, which states without further elaboration that ‘[t]he provisions of this Act shall not affect the historical rights of the People’s Republic of China’” (emphasis added in the DOS report). China’s 2011 Note Verbale89 says that Beijing’s claims are supported by “historical and legal evidence”, but while the DOS report adds emphasis to “historical”, one should be careful not to confuse a historical claim with a claim supported by history. A country may put forward historical evidence in both negotiations and arbitration or adjudication in areas where UNCLOS refers to “equitable” solutions. The text also notes how many “Chinese institutions and commentators have considered that the dashed-line maps depict China’s historic title or historic rights”.

The DOS reports explains that “some” Chinese Government actions and statements which are “inconsistent with” UNCLOS, while not amounting to “express assertions of a historic claim, they may indicate that China considers that it has an alternative basis – such as historic title or historic rights – for its maritime claims in the South China Sea”, and provides some examples, such as the assertion by a MFA spokesperson that the Second Thomas Shoal (Ren’ai Reef) is under Chinese “sovereignty”.90 This mantra about sovereignty, together with repeated appeals to history, could indeed be considered as evidence that what Beijing has in mind is a historic claim. Furthermore, it may well be a claim going beyond the provisions for such term in UNCLOS.

Next the DOS report examines two issues: whether China has actually “Made a Historic Claim”, and whether it would “have Validity”. Concerning the former, the text states that “China has not actually made a cognizable claim to either ‘historic waters’ or ‘historic rights’”, the reasons being a lack of “international notoriety” and the statement in her 1958 Territorial Sea Declaration that “high seas” separate the Chinese mainland and coastal islands from “all other islands belonging to China”. The text admits that the expression “historic waters” appears in some Chinese legislation and statements, and actually cites some of them, but believes that this does not amount to “notoriety” to a degree sufficient to “at the very least” allow “other states” to “have the opportunity to deny any acquiescence with the claim by protest etc.”91 since “no Chinese law, declaration, proclamation, or other official statement” exists “describing and putting the international community on notice of a historic claim”.

Whereas the assertion that China has not actually made a claim may not be shared by everybody, in particular given the language flowing from Beijing which the DOS report itself cites, the reference to the “high seas” between mainland China and some islands seems stronger proof that Beijing was not making a historic claim. However, we must again stress that this would be the case if we followed the prevailing interpretation of the law of the sea, but there is no reason why China should adhere strictly to it, and even less that Beijing should not have changed her mind since 1958, when she had little more than a coastal navy and her economy was closed and in tatters. It may be true, as the report notes, that the 1958 Declaration only made a historic claim to the Bohai (Po-hai) gulf in northeastern China, but again this should perhaps be judged from a wider historical perspective. After 1949 the PRC took a much more uncompromising stance concerning its North-East than its South-East (and wider maritime) borders. With a pragmatic arrangement in place with the United Kingdom concerning Hong Kong, and a strong economic and political relation with the Soviet Union, it was at the other end of the country where, in 1950, Beijing (not without an intense internal debate given the state of the country), decided to resort to force to prevent the presence of hostile forces close to her border, intervening in the Korean War, pushing back the advancing Allied forces and reversing the impact of the Inchon landing, ultimately forcing a stalemate on the ground. In 1958, just five years after the Korean armistice, nearby waters may have thus been much more present in Chinese leaders’ minds. In addition, these were also the waters directly leading to Tianjin and Beijing, the venue for foreign interventions in both the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion. It would not be until the late 1970s that China’s South-Eastern flank would begin to receive more attention, in part thanks to the rapprochement with the United States and in particular once economic growth and the country’s move to become a net energy and commodity importer turned the waters of the South China Sea into a vital venue and potential choke point. It is true that in December 1941 the loss of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse in the South China Sea had enabled the Japanese to land in Malaya and ultimately conquer Burma, closing the last land route to besieged Nationalist China, but this did not result in a comparable imprint on China’s historical consciousness, among other reasons because the episode did not involve Chinese naval forces and was subsumed into a much larger, dramatic, and quickly-developing picture.

Concerning whether, if China “Made a Historic Claim”, it would “have Validity”, the DOS paper insists that “such a claim would be contrary to international law.” The text does not stop at arguing that it is not open to a state to make historic claims based not on UNCLOS but on general international law, laying down a second line of defense. It explains that, “even assuming that a Chinese historic claim in the South China Sea were governed by ‘general international law’ rather than the Convention”, it would still be invalid since it would not meet the necessary requirements under general international law, namely “open, notorious, and effective exercise of authority over the South China Sea”, plus “continuous exercise of authority” in those waters and “acquiescence by foreign States” in such exercise of authority. Furthermore, it explains that the United States, which “is active in protesting historic claims around the world that it deems excessive”, has not protested “the dashed line on these grounds, because it does not believe that such a claim has been made by China”, with Washington choosing instead to request a clarification of the claim. Whether this view is also meant to avoid a frontal clash with Beijing, in line with the often state policy goal of “managing” rather than “containing” China’s rise, is something not discussed in the text.

|

The Spratly Islands, a bone of contention between China and the Philippines |

Two Further Aspects to the US Position

The Department of State’s paper emphasizes that “The United States has repeatedly reaffirmed that it takes no position as to which country has sovereignty over the land features of the South China Sea”92

The trouble with this view, apart from the possibility that a measure of ambiguity in the San Francisco Treaty may be in Washington’s interest, is that the United States is no mere external power in the South China Sea, given two essential historical facts that the Department of State’s paper never mentions. The first is the period of US sovereignty over the Philippines following the Spanish-American War of 1892, and the resulting Treaties of Paris93 and Washington,94 which among others determined the territorial extent of the Archipelago. The second is the Second Indochina War, more often known as the Vietnam War, when American forces together with those from other Allied nations operated in the region in support of the Republic of Vietnam.

The Treaties of Paris and Washington are important because they amount to the United States being, at least until Filipino independence, a littoral state in the South China Sea. Furthermore, the territory of the Republic of the Philippines is inherited from the United States, precisely around the time when China, at that time the Republic of China, is beginning to publicly assert its claims in the South China Sea. While this paper will not examine this issue in depth, it seems clear that American authorities are in no position to simply claim that they have nothing to say on the ultimate issue of sovereignty, as if the Philippines had never been under US sovereignty and Washington had never signed any treaty dealing with the extent of its territory.

The Second Indochina War is not as significant, but it still means that for years US forces operated in some of the regions under dispute, following agreements with the Republic of Vietnam and other states in the region, including the Philippines. Although again not the purpose of this paper, any examination in depth of American policy concerning the territorial dispute over the South China Sea cannot ignore this episode. Instead, the diplomatic history of the period should be examined in the search for evidence of any event or document of legal significance.

|

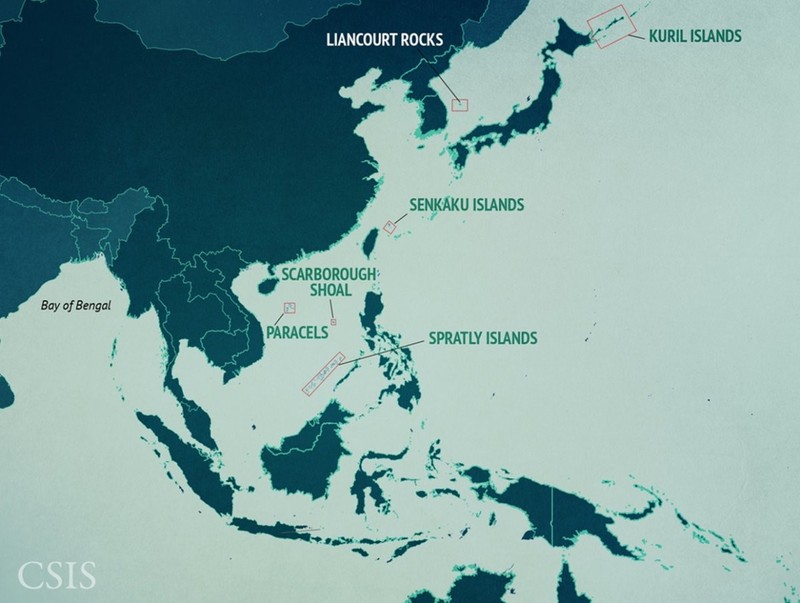

Map showing the location, within the South China Sea, of the Paracels, the Spratlys, and Scarborough Shoal |

Russia: Just a Silent Observer?

A look at Russian policy towards the South China Sea may begin with the observation that, while all other regional and extra-regional actors seem to have growing geopolitical tensions with China, Moscow appears to be strengthening ties with Beijing at a time of increasing isolation and economic trouble, as in areas including energy, the Ukraine, and the Arctic. However, it is necessary to examine Russian national interests and actual decisions on the ground, while being aware that Russian sources are most reluctant to deviate from the official narrative of friendship with China. This reluctance was clear in last year’s new military doctrine, which did not contemplate a possible conflict with Beijing95 despite recognition of military imbalance in the Far East, one of the factors behind the Russian military reforms. Russian military doctrine may not refer to China, but “counter-terrorism” drills in the Far East usually feature the simulated employment of tactical nuclear weapons, hardly the first tool that comes to mind when confronting a terrorist attack. Although Chinese leaders avoid referring to it in public, a significant portion of Russia’s Far East remains an unfairly lost land in their eyes.96

Even before the current spike in tensions in the Euro-Atlantic Region, Russia had determined to diversify energy exports, increasing the share of oil and natural gas exports going to the Asia-Pacific. While agreements with China have attracted the most media and scholarly attention, Moscow has been working on a wide range of projects, including a possible natural gas pipeline to South Korea through the DPRK97 and civilian nuclear cooperation with Vietnam. Concerning Japan, Moscow was quick to offer support through increased LNG exports in the wake of Fukushima,98 and while observers differ on the realistic prospects of a grand bargain, some cautioning that relations with Russia are the most difficult dossier on Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s table, a strong rationale remains for closer links between Russia and Japan. This does not mean that this rationale will overcome bilateral obstacles such as the territorial conflict over the Northern Territories / Southern Kuriles and challenges associated with Japan’s difficulties in maneuvering away from American positions in the face of growing tensions with China, but it should at least caution against simplistic explanations. Furthermore, while Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s latest visit to the Kurile Islands / Northern Territories in August 201599 again prompted criticism in Japan, this has not prevented Medvedev himself from signing into Russian law the extension of the country’s continental shelf into the Okhotsk Sea, as agreed with Japan and in line with Moscow’s February 2013 application to the UN Commission on continental shelves.100 Russia may have traditionally looked Westward, from Peter the Great101 to Lenin,102 but it is indeed a Pacific power, and its diplomacy features a wide range of relations with countries in the region. Faced with the need to develop her Far East, diversify away from Europe, avoid over reliance on China, and generally speaking maximize national power and influence and economic exchanges, we could perhaps talk about Russia’s own “Pivot” or “Rebalance” to the Pacific.103 According to Stephen Blank (Senior Fellow for Russia at the American Foreign Policy Council), “Justified emphasis on the current Ukraine crisis should not lead us to make the mistake of overlooking Russia’s policies in East Asia”. This author points out how Russia is using energy and weapons sales in the region, in line with Moscow’s traditional diplomatic practice, adding that “like other powers, Russia is pursuing what may be called a hedging strategy against China in Asia. On the one hand it supports China against the US and on the other works to constrain Chinese power in Asia”. Blank concludes that “Sino-Russian amity, at least in regard to the Asian regional security agenda, is something of a facade”, meaning that “Russo-Chinese ties may not be as dangerous for the US as some have feared, although there is no reason for complacency since the two governments will clearly collude to block numerous American initiatives globally”.104

Among other areas, Moscow may be seeking greater influence on the Korean Peninsula,105 the participation of Asian powers other than China in the Russian Arctic,106 greater cooperation with Indonesia, and, although regularly denied, the sale of Russian submarines (or transfer of technology) to Taiwan.107 One of the most striking aspects of the Russian presence in the Pacific, and in particular the South China Sea, is Moscow’s continued support for Hanoi and sale of advanced weapons, chief among them Kilo-class submarines. Russia is not just an essential lynchpin in Vietnam’s asymmetrical warfare strategy, it has avoided publicly supporting China’s stance in the region. This failure to speak out in favor of Beijing is not restricted to the South China Sea, as noted by Mu Chunshan “Even on the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute between China and Japan, Russia has kept an ambiguous position”. Mu lists four reasons for this. First, “China and Russia are not allies. There is no alliance treaty between them”, so Moscow is not bound to support Beijing politically or militarily, still less in “The South China Sea”, which “is not a place where Russia can expand its interests, nor is it necessary for Russia to interfere in this region absent a formal alliance with China”. Second, “Russia enjoys good relations with countries bordering the South China Sea and does not need to offend Southeast Asia for the sake of China”. This does not just apply to Vietnam, since for example “Russia also enjoys a good relationship with the Philippines”. Third, with Moscow focused on Europe and the Ukrainian crisis, “Russia has neither the desire nor the ability to confront the U.S. in the South China Sea”. Finally, “the development of China has actually caused some worries within Russia”, with concerns centered on possible encroachment in the Russian Far East. However, according to Mu Chunshan this does not mean that there is a split between Moscow and Beijing, since the two countries know each other well and Russia’s silence on the South China Sea, like China’s on the Crimea, does not mean they oppose each other. Beijing’s abstention at the UNSC on Crimea “doesn’t mean that China opposes Russia’s position. By the same logic, Russia’s neutral stance in the South China Sea disputes doesn’t mean that Russia doesn’t support China”. Generally speaking, “China and Russia leave each other ample room for ambiguous policies, which is actually proof of an increasingly deep partnership. This arrangement gives both China and Russia the maneuvering space they need to maximize their national interests”.108

Vietnam has not only recently received her third enhanced Kilo-class submarine, HQ 194 Hai Phong,109 but is building four Tarantul-class orMolniyacorvettes at Ba Son Shipyards, under license from Russia’s Almaz Central Design Bureau. Two corvettes were previously delivered in June 2014.110 Furthermore, Cam Ranh Bay remains of the utmost importance to the Russian Navy, and in November 2014 Hanoi and Moscow signed an agreement to facilitate the use of the base by Russian warships.111 According to this agreement, in future Russian warships will only have to notify port authorities immediately prior to their arrival, the agreement privileging the Russian Navy and giving it special access, whereas other navies are restricted to one port visit per year.112

Russia is also a nuclear energy partner for Hanoi, and has ignored Chinese injunctions to abandon offshore oil cooperation with Vietnam in the South China Sea.113 Speaking to the Vietnamese media in advance of his official trip in April this year, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev confirmed plans for “a free trade area agreement. It will likely be the first such agreement to be signed between the Eurasian Economic Union and an individual country”, while identifying Vietnamese tourism in Russia and trade settlement in their respective national currencies as areas for further work.114 While defense links with Russia are a cornerstone of Vietnam’s multi-vector diplomacy, they go hand in hand with growing links with the United States. As often happens with countries engaging a wide range of powers which may otherwise be at odds, such a balancing act is not always easy and may result in pressure by one partner to restrict cooperation with the other. Recently, use of Cam Ranh Bay air facilities by Russian Il-78 Midas tanker planes refueling Tu-95 “Bear” strategic bombers, involved among others in sorties to Guam, prompted a request by Washington to Hanoi to terminate such access.115

We can conclude that Moscow is determined not to become too dependent on Beijing, and that despite many domestic and bilateral obstacles it wishes to become a major Pacific power. This may offer some opportunities to the United States in the event of a turn for the worse in Sino-American relations, but in addition to the many challenges it would pose, right now this appears an unlikely scenario given the deep mistrust of Russia in Western quarters in general and Washington in particular.116 Together with the absence of any mention of sanctions when discussing policy options in the South China Sea, and the apparent disconnect between the US “rebalance” and the country’s nuclear posture, this deep schism between Russia and the West constitutes a triad of factors objectively enhancing China’s position when dealing with her neighbors. Unlike Moscow, Beijing seems to be succeeding in preventing a regional territorial conflict from having a major impact on bilateral relations with Washington.

India: Looking East

As a quasi-island, vitally dependent on sea lanes of communication, India cannot afford to ignore developments in the South China Sea, a body of water connecting the country to, among others, Japan. In recent years New Delhi has supported Hanoi in two crucial ways, first by cooperating in offshore oil exploration and production, and second in helping build the country’s maritime security capabilities. This may be seen as part of New Delhi’s “Look East” policy,117 and also as partially motivated by a desire to make it more difficult for China to dominate the South China Sea and thus more easily access the Indian Ocean and increase pressure on India. However, while this may make sense, and fit with other Indian policies such as improving border infrastructures118 in the Himalayas and developing key weapons systems such as Brahmos,119 it does not mean that it is necessarily part of any “grand design” to encircle China. While true that India has gradually developed a wide range of relations with other countries in the region, including joint military drills, the often grand-sounding words employed to describe them rarely match their actual contents. For example, while relations with Japan are important and benefit from the personal warmth between the two prime ministers,120 New Delhi and Tokyo are yet to conclude a civil nuclear agreement, which would certify the end to India’s “nuclear apartheid”. New Delhi remains cautious concerning China, and rather than engage in a multinational alliance against Beijing, Brahma Chellaney has more accurately described the country as having moved “from nonaligned to multialigned”121 under a prime minister whose foreign policy “hallmark” is “pragmatism”.122