Akutagawa Ryunosuke

Translated by Jay Rubin

Akutagawa Ryunosuke (1892-1927) is known primarily for his stories set in other times and places, but even at their most exotic or fantastic, his works deal with urgent modern themes. His Edo-period samurai stories emphasize the horror of violence and the emptiness of vengeance. “Shogun” (The General, 1924), a well-known portrait of a victorious general resembling Nogi Maresuke (1849-1912), the “hero” of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, is a bitter satire of a man responsible for the death of thousands. “The Story of a Head That Fell Off,” set against the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, is an intense cry against the absurdity of war that unfortunately remains as relevant in our barbaric twenty-first century as it was in Akutagawa’s day.

In the Sino-Japanese War, Japan’s first foreign war in modern times, China and Japan fought over control of Korea. Japan succeeded in capturing the valuable Liaodong peninsula from China but was soon forced to return it by the “Triple Intervention” of Russia, Germany and France, which laid the groundwork for the Russo-Japanese War. The central character of this story, He Xiao-er (Kashoji in Japanese), is a Chinese soldier caught in the first struggle for Liaodong. This is not the only story in which Akutagawa’s imagination and scholarship enabled him to adopt the “enemy” point of view. In one brief, startling piece on the political misuse of history, “Kin-shogun” (General Kim, 1922), he incorporated Korean legend into a tale concerning Hideyoshi’s 1598 invasion of Korea.

The translation of “The Story of a Head That Fell Off” omits most mentions of the protagonist’s surname to avoid confusion with the English pronoun.

Xiao-er threw his sword down and clutched at his horse’s mane, thinking I’m sure my neck’s been cut. No, perhaps the thought crossed his mind only after he started hanging on. He knew that something had slammed deep into his neck, and at that very moment he grabbed hold of the mane. The horse must have been wounded, too. As Xiao-er flopped over the front of his saddle, the horse let out a high whinny, tossed its muzzle toward the sky, and, tearing through the great stew of allies and enemies, started galloping straight across the corn field that stretched as far as the eye could see. A few shots might have rung out from behind, but to Xiao-er they were like sounds in a dream.

Trampled by the furiously galloping horse, the man-tall corn stalks bent and swayed like a wave, snapping back to sweep the length of Xiao-er’s pigtail or slap against his uniform or wipe away the black blood gushing from his neck. Not that he had the presence of mind to notice. Seared into his brain with painful clarity was nothing but the simple fact that he had been cut. I’m cut. I’m cut. His mind repeated the words over and over while his heels kicked mechanically into the horse’s lathered flanks.

Ten minutes earlier, Xiao-er and his fellow cavalrymen had crossed the river from camp to reconnoiter a small village when, in the yellowing field of corn, they suddenly encountered a mounted party of Japanese cavalry. It happened so quickly that neither side had time to fire a shot. The moment the Chinese troops caught sight of the enemy’s red-striped caps and the red ribbing of their uniforms, they drew their swords and headed their horses directly into them. At that moment, of course, no one was thinking that he might be killed. The only thing in their minds was the enemy: killing the enemy. As they turned their horses’ heads, they bared their teeth like dogs and charged ferociously toward the Japanese troops. Those enemy troops must have been governed by the same impulse, though, for in a moment the Chinese found themselves surrounded by faces that could have been mirror images of their own, with teeth similarly bared. Along with the faces came the sound of swords swishing through the air all around them.

From then on, Xiao-er had no clear sense of time. He did have a weirdly vivid memory of the tall corn swaying as if in a violent storm, and of a copper sun hanging above the swaying tassels. How long the commotion lasted, what happened during that interval and in what order– none of that was clear. All that while, Xiao-er went on swinging his sword wildly and screaming like a madman, making sounds that not even he could understand. His sword turned red at one point, he seemed to recall, but he felt no impact. The more he swung his sword, the slicker the hilt grew from his own greasy sweat. His mouth felt strangely dry. All at once the frenzied face of a Japanese cavalryman, eyeballs ready to pop from his head, mouth straining open, flew into the path of Xiao-er’s horse. The man’s burred scalp shone through a split in his red-striped cap. At the sight, Xiao-er raised his sword and brought it down full force on the cap. What his sword hit was not the cap, though, nor the head beneath it, but rather the other man’s steel slashing upward. Amid the surrounding pandemonium, the clash of swords resounded with a terrifying transparency, driving the cold smell of filed iron sharply into his nostrils. Just then, reflecting the glare of the sun, a broad sword rose directly above Xiao-er’s head and plunged downward in a great arc. In that instant, a thing of indescribable coldness slammed into the base of his neck.

The horse went on charging through the corn field with Xiao-er on its back, groaning from the pain of his wound. The densely planted corn would never give out, it seemed, no matter how long the horse kept running. The cries of men and horses, the clash of swords had faded long before. The autumn sun shone down on Liaodong just as it does in Japan.

Again, Xiao-er, swaying on horseback, was groaning from the pain of his wound. The voice that escaped his firmly gritted teeth, however, was more than a groan: it carried a somewhat more complex meaning. Which is to say that he was not simply moaning over his physical pain. He was wailing because of his psychological pain, because of the dizzying ebb and flow of his emotions, centering on the fear of death.

He felt unbearable sorrow to be leaving this world forever. He also felt deep resentment toward the men and events that were hastening his departure. He was angry, too, at himself for having allowed this to happen. And then–each one calling forth the next–a multitude of emotions came to torment him. As one gave way to another, he would shout, “I’m dying! I’m dying!” or call out for his father or mother, or curse the Japanese cavalryman who did this to him. As each cry left his lips, however, it was transformed into a meaningless, rasping groan, so weak had he become.

I’m the unluckiest man alive, coming to a place like this to fight and die so young, killed like a dog, for nothing. I hate the Japanese who wounded me. I hate my own officer who sent me out on this reconnaissance mission. I hate the countries that started this war–Japan and China. And that’s not all I hate. Anyone who had anything to do with making me a soldier is my enemy. Because of all those people, I now have to leave this world where there is so much I want to do. Oh, what a fool I was to let them do this to me!

Investing his moans with such meaning, Xiao-er clutched at the horse as it bounded on through the corn. Every now and then a flock of quail would flutter up from the undergrowth, startled by the powerful animal, but the horse paid them no heed. It was unconcerned, too, that its rider often seemed ready to slide off its back, and it charged ahead, foaming at the mouth.

Had fate permitted it, Xiao-er would have gone on tossing back and forth atop the horse all day, bemoaning his misfortune to the heavens until that copper sun sank in the western sky. But when a narrow, muddy stream flowing between the corn stalks opened in a bright band ahead of him where the plain began to slope gently upward, fate took the shape of two or three river willows standing majestically on the bank, their low branches still dense with leaves just beginning to fall. As Xiao-er’s horse passed between them, the trees suddenly scooped him up into their leafy branches and tossed him upside-down onto the soft mud of the bank.

At that very instant, through some associative connection, Xiao-er saw bright yellow flames burning in the sky. They were the same bright yellow flames he used to see burning under the huge stove in the kitchen of his childhood home. Oh, the fire is burning, he thought, but in the next instant he was already unconscious.

Was Xiao-er entirely unconscious after he fell from his horse? True, the pain of his wound was almost gone, but he knew he was lying on the deserted riverbank, smeared in mud and blood, and looking up through the willow leaves caressing the deep blue dome of the sky. This sky was deeper and bluer than any he had ever seen before. Lying on his back, he felt as if he were looking up into a gigantic inverted indigo vase. In the bottom of the vase, clouds like massed foam would appear out of nowhere and then slowly fade as if scattered by the ever-moving willow leaves.

Was Xiao-er, then, not entirely unconscious? Between his eyes and the blue sky passed a great many shadow-like things that were not actually there. First he saw his mother’s slightly grimy apron. How often had he clung to that apron in childhood, in both happy times and sad? His hand now reached out for it, but in that instant it disappeared from view. First it grew thin as gossamer, and beyond it, as through a layer of mica, he could see a mass of white cloud.

Next there came gliding across the sky the sprawling sesame field behind the house he was born in–the sesame field in midsummer, when sad little flowers bloom as if waiting for the sun to set. Xiao-er searched for an image of himself or his brothers standing in the sesame plants, but there was no sign of anything human, just a quiet blend of pale flowers and leaves bathed in pale sunlight. It cut diagonally across the space above him and vanished as if lifted up and away.

Then something strange came slithering across the sky–one of those long dragon lanterns they carry through the streets on the night of the lantern festival. Made of thin paper glued to a bamboo frame a good thirty feet long, it was painted in garish greens and reds, and it looked just like a dragon you might see in a picture. It stood out clearly against the daytime sky, lighted from within by candles. Stranger still, it seemed to be alive, its long whiskers waving freely. Xiao-er was still taking this in when it swam out of his view and quickly vanished.

As soon as the dragon was gone, the slender foot of a woman came to take its place. A bound foot, it was no more than three inches long. At the tip of its gracefully curved toe, a whitish nail softly parted the color of the flesh. In Xiao-er’s heart, memories of the time he saw that foot brought with them a vague, far-off sadness, like a fleabite in a dream. If only he could touch that foot again–but no, that would never happen. Hundreds of miles separated this place from the place where he had seen that foot. As he dwelt on the impossibility of ever touching it again, the foot grew transparent until it was drawn into the clouds.

At that point Xiao-er was overcome by a mysterious loneliness such as he had never experienced before. The vast blue sky hung above him in silence. People had no choice but to go on living their pitiful lives beneath that sky, buffeted by the winds that blow down from above. What loneliness! And how strange, he thought, that he had never known this loneliness until now. Xiao-er released a lengthy sigh.

All at once the Japanese cavalry troops with their red-striped caps charged in between his eyes and the sky, moving with far greater speed than any of the earlier images, and disappearing just as quickly. Ah yes, those cavalrymen must be feeling a loneliness as great as mine. Had they not been mere apparitions, he would have wanted to comfort them and be comforted by them, to forget this loneliness if only for a moment. But it was too late now.

Xiao-er’s eyes overflowed with tears. And when, with those tear-moistened eyes, he looked back on his life, he recognized all too well the ugliness that had filled it. He wanted to apologize to everyone, and he also wanted to forgive everyone for what they had done to him.

If I escape death today, I swear that I will do whatever it takes to make up for my past.

Xiao-er wept as he formed these words deep in his heart. But, as if unwilling to listen, the sky, in all its infinite depth, in all its infinite blueness, slowly began to press down upon him where he lay, foot by foot, inch by inch. Faintly sparkling points in the vast blue expanse were surely stars visible in daylight. No longer did he see shadowy images passing before him. Xiao-er sighed once more, felt a sudden trembling of the lips, and, in the end, let his eyelids slowly close.

A year had gone by since the signing of the peace treaty between China and Japan. One morning in early spring, Major Kimura, military attaché to the Japanese legation in Beijing, and Dr. Yamakawa, a technician on official tour of inspection from the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce in Tokyo, were seated at a table in the legation office. They were enjoying a quiet conversation over coffee and cigars in a momentary diversion from the press of their duties. Despite the season, a fire was burning in the wood stove and the room was warm enough to bring out perspiration. Every now and then, the potted red plum on the table wafted a distinctively Chinese fragrance into the air.

Their conversation centered on the Empress Dowager [1] for a while but eventually turned to recollections of the Sino-Japanese War, at which point Major Kimura suddenly stood up and brought over a bound copy of a Chinese newspaper from a rack in the corner. Spreading it open on the table before Dr. Yamakawa, he pointed to the page with a look in his eyes that said, “Read this!” Dr. Yamakawa was startled by this sudden gesture, but he had long known that Major Kimura was a good deal more sophisticated and witty than the typical military man, and he expected to find a bizarre anecdote relating to the war. He was not disappointed. In impressive rows of square Chinese characters, the article said:

A man named He Xiao-er, owner of a barber shop on ______ Street, served with great distinction in the Sino-Japanese War and was cited for numerous acts of valor. Following his triumphant homecoming, however, he tended to indulge in dissolute behavior, debauching himself with drink and women. At the X Bar last ____day, he was arguing with his drinking companions and a scuffle broke out, at the conclusion of which he suffered a severe neck wound and died instantaneously. The strangest thing was the wound to the neck, which was not inflicted by a weapon during the incident. It was, rather, the reopening of a wound that Xiao-er had suffered on the battlefield. According to one eyewitness, a table fell over and the victim fell with it. The moment he hit the floor, his head fell off, remaining attached by only one strip of skin and spilling blood everywhere. The authorities are said to have serious doubts about the truth of this account and to be engaged in a determined search for the perpetrator, but since Strange Tales of Liaozhai contains the account of a man’s head falling off, [2] can we say for certain that such a thing could not have happened to someone such as He Xiao-er?

Dr. Yamakawa had a shocked expression on his face when he finished reading the article. “What is this?” he asked.

Major Kimura released a long, slow stream of cigar smoke and, with a mellow smile, said, “Fascinating, don’t you think? A thing like this could only happen in China.”

“True,” Doctor Yamakawa answered with a grin, knocking the long ash on his cigar into an ashtray. “It’s simply unthinkable anyplace else.”

“There’s more to the story, though,” Major Kimura said, pausing with a somber expression on his face. “I know the fellow, Xiao-er.”

“You know him? Oh, come on, don’t tell me a military attaché is going to start lying on a par with a newspaper reporter.”

“No, of course I wouldn’t do anything so ridiculous. When I was wounded back then in the battle of ______ Village, Xiao-er was being treated in our field hospital. I talked to him a few times to practice my Chinese. He had a neck wound, so chances are 8 or 9 out of 10 it’s the same man. He told me he was on some kind of reconnaissance mission when he ran into some of our cavalrymen and got slashed in the neck.”

“What a strange coincidence. The paper says he was a real trouble-maker, though. We would have all been better off if a fellow like that had died on the spot.”

“Yes, but at the time he was a good, honest man, one of the best-behaved prisoners of war. The army doctors all seemed to have a soft spot for him and gave him extra-good treatment. I enjoyed the stories he told me about himself, too. I especially remember the way he described his feelings when he was badly wounded in the neck and fell off his horse. He was lying in the mud on a river bank, looking up at the sky through some willows, when he saw his mother’s apron and a woman’s bare foot and a sesame field in bloom–all right there in the sky.”

Major Kimura threw his cigar away, brought his coffee cup to his lips, glanced at the red plum on the table, and went on as if talking to himself, “When he saw those things in the sky, he began to feel deeply ashamed of the way he had lived his life until then.”

“So he turned into a trouble-maker as soon as the war ended? It just goes to show, you can’t trust anybody.” Dr. Yamakawa rested his head against the chair back, stretched his legs out and, with an ironic air, blew his cigar smoke toward the ceiling.

“Can’t trust anybody? You mean, you think he was faking it?”

“Of course he was.”

“No, I don’t think so. I think he was serious about the way he felt–at the time, at least. And I’ll bet he felt the same way again the moment ‘his head fell off’ (to use the paper’s phrase). Here’s how I imagine it: He was drunk when he was fighting, so the other man had no trouble throwing him down. When he landed, the wound opened up, and his head rolled onto the floor with its long pigtail hanging down. This time again, the same things passed in front of his eyes: his mother’s apron, the woman’s bare foot, the sesame field in bloom. And even though there was a roof in the way, he maybe even saw a deep, blue sky far overhead. Again, he felt deeply ashamed of his life until then. This time, though, it was too late. The first time, a Japanese medical-corps man found him unconscious and took care of him. This time, the other man kept punching him and kicking him. He died full of regrets.”

Dr. Yamakawa’s shoulders shook with his laughter. “What a dreamer you are! If what you say is true, though, why did he let himself become a trouble-maker after the first time?”

“That’s because, in a way different from what you meant by it, you can’t trust anybody.” Major Kimura lit a new cigar and, smiling, continued in tones that were almost exultantly cheerful. “It is important–even necessary–for us to become acutely aware of the fact that we can’t trust ourselves. The only ones you can trust to some extent are people who really know that. We had better get this straight. Otherwise, our own characters’ heads could fall off like Xiao-er’s at any time. This is the way you have to read all Chinese newspapers.”

(December 1917)

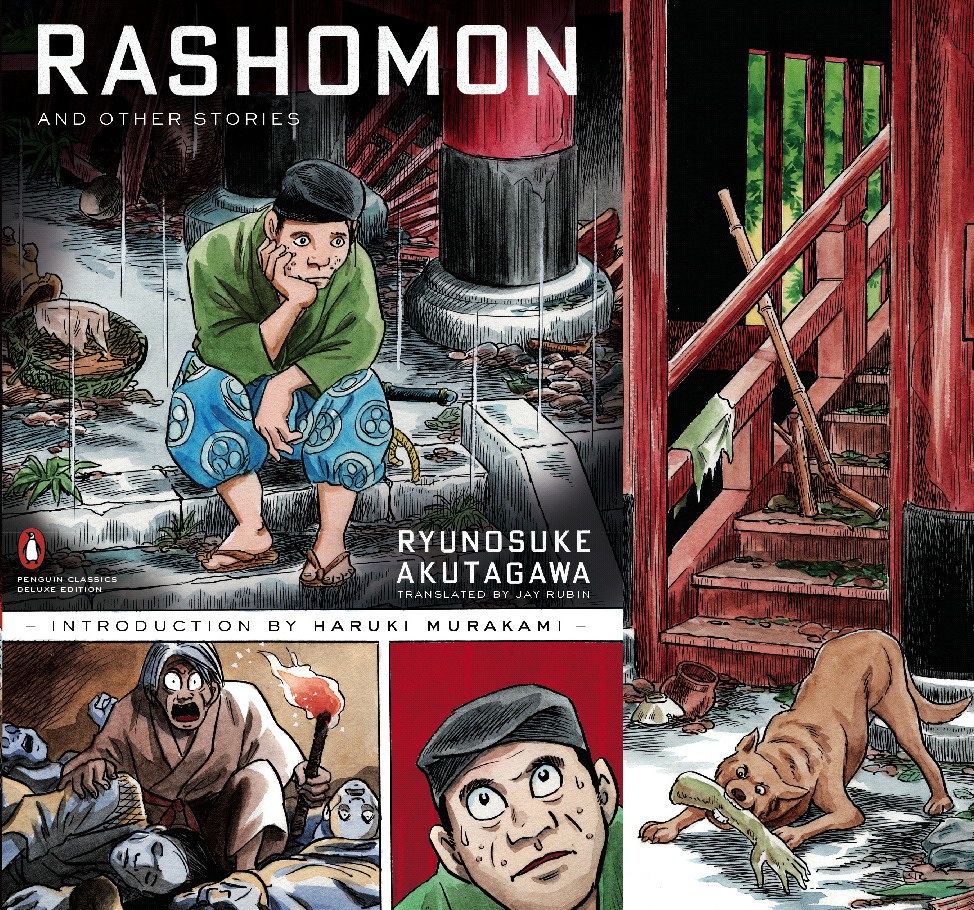

Reprinted by arrangement with Penguin Classics, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from Rashomon and Seventeen Other Stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, translated from the Japanese by Jay Rubin. Copyright © 2006 by Jay Rubin.

Jay Rubin has translated Natsume Soseki’s novels Sanshiro and The Miner and Murakami Haruki’s Norwegian Wood, The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, and after the quake. He is the author of Injurious to Public Morals: Writers and the Meiji State and has been a professor of Japanese literature at the University of Washington and at Harvard University.

Posted at Japan Focus on August 3, 2007.

Notes

[1] Empress Dowager: Cixi (1835-1908), the powerful “Last Empress” of China.

[2] Strange Tales of Liaozhai: The collection of supernatural tales is Liao zhai zhi yi by Pu Songling (1640-1715), which has been partially rendered into English as Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, tr. John Minford (London: Penguin Books, 2006), and Strange Tales of Liaozhai. Story 72, “A Final Joke” (in Minford’s edition), tells how a certain man named Jia literally laughed his head off many years after receiving a near-fatal wound. It gave Akutagawa the idea for this story according to Kono Toshiro et al., eds., Akutagawa Ryunosuke zenshu, 24 vols. (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1995-8) 3:394.