Yasukuni Shrine: History, Memory, and Japan’s Unending Postwar (University of Hawaii Press and Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University, 2015) examines key moments in the one-and-a-half-century history of Yasukuni Shrine, beginning with its conceptualization in the late Tokugawa years and culminating in the political turmoil of the twenty-first century. I decided to write a book on the history of the Shrine for a seemingly counter-intuitive reason: there is too much attention on this monument—political attention, that is.

Yasukuni Shrine remains one of the focal points in the domestic and international debates on how Japan remembers and acts on its wartime past. In the ongoing debates, Yasukuni Shrine has come to take on a singular presence—an institution that represents Japan’s unresolved war crimes. Critics of the shrine argue that Yasukuni Shrine signifies Japan’s desire to return to the military-driven expansionist state that it was during the Asia-Pacific War. Supporters contend that it is a memorial for those who died for the nation.

|

Yasukuni Shrine: History, Memory, and Japan’s Unending Postwar is an attempt to complicate the history of the Shrine. It demonstrates that Yasukuni Shrine was a space with unstable meaning that changed significantly over time. It highlights the various ways that Japanese people became actors—whether willingly or unwillingly, consciously or unconsciously—in Japan’s quest for empire.

We may confront “Yasukuni” from three perspectives: Yasukuni the belief (Yasukuni shinkō), Yasukuni the site (Yasukuni Jinja), and Yasukuni the issue (Yasukuni mondai). “Yasukuni the belief” is the myth that developed during imperial Japan: that war death and the resulting enshrinement at Yasukuni Shrine was the highest honor a man could achieve. “Yasukuni the site” refers to the physical space that is both a Shinto shrine and a war memorial, as well as the spatial practices within it. “Yasukuni the issue” includes the postwar political problems currently associated with the shrine. These elements are intertwined. The shrine site and the associated spatial practices are intertwined with the beliefs and issues. The operators of “Yasukuni the site” promote “Yasukuni the belief” and therefore play a major role in intensifying “Yasukuni the issue.”

Most discussions of Yasukuni Shrine, and particularly those by its critics, reduce the complex history and memories of Japan’s wartime past to one ambiguous “Yasukuni,” giving the impression that an intervention into (or severing state ties with) the physical presence of the shrine could resolve all of the issues associated with the Asia-Pacific War. This focus on the shrine—and by extension the wartime military and political leaders who created and supported it—ironically reinforces the narrative of victimhood prevalent in Japan today. Namely, that during the Asia-Pacific War, ordinary Japanese were victims of the wartime state (embodied by Yasukuni Shrine and the Class-A war criminals enshrined there). This stark separation of victim and perpetrator roles in wartime Japan obstructs a necessary effort to reconcile with non-Japanese victims of the war. It also affects the ways that contemporary Japanese remember, assess, and preserve memories of their war experiences, and act upon those memories.

The following examines the earliest phase in the creation of “Yasukuni the belief,” the process through which Yasukuni Shrine was conceptualized in late Tokugawa Japan.

Today on the way to the villa I passed through the temple grounds of Ueno. The two-story gate and most of the buildings were burned in the battle last summer; so now the grandeur of the past is but a dream. I want to purify this ground, and dedicate it as a memorial to the war dead.

Kido Takayoshi, The Diary of Kido Takayoshi

On January 15, 1869, statesman Kido Takayoshi noted in his diary that the Kan’eiji site in Ueno, which he walked through earlier that day, should be purified and transformed into a memorial for the war dead.1 He was, in fact, proposing that Ueno, once bustling with patrons of the Kan’eiji temple but now devastated after the Battle of Ueno the previous year, should house a memorial for the imperial loyalists who fell during the Restoration. In short, Kido was recommending that an institution akin to what would become Yasukuni Shrine be built at Ueno. Kido’s proposal did not materialize, however. Ōmura Masujirō, who soon would become the Vice Minister of the newly created Army Ministry, opposed Kido’s choice, arguing that the spirits of the dead bakufu soldiers—enemy casualties of that battle—haunted the site. Furthermore, the land was unavailable, as the Meiji government announced shortly thereafter that it had designated the Ueno site for a new university hospital. Instead, Ōmura selected a stretch of land atop Kudan Hill that had been controlled by the bakufu infantry—the site that Yasukuni Shrine currently occupies. He recommended it as the most auspicious location for the Imperial Palace: the site was situated to the northwest of the palace, the direction in need of protection.2

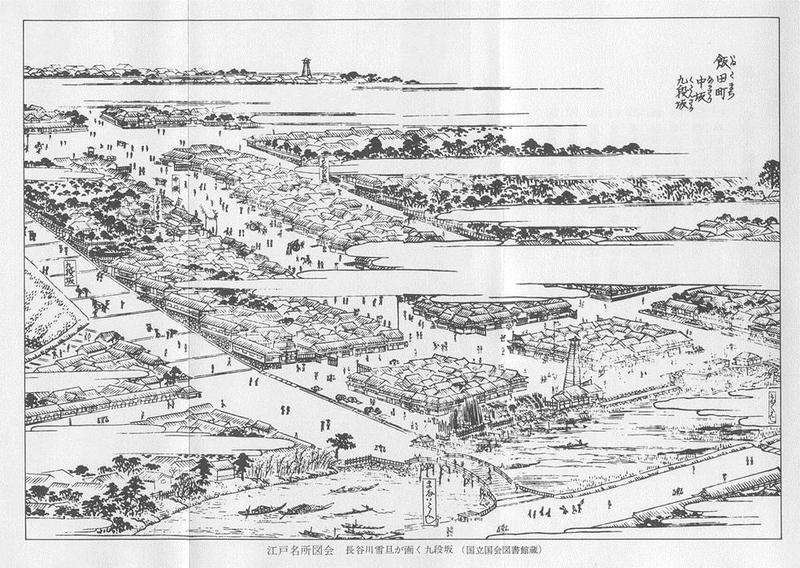

Ōmura had grand plans. He predicted that the Kudan site, with its proximity to the Imperial Palace and a commanding view of Tokyo, would become a strategic spot in case of armed domestic conflict. Thus, it was—at least symbolically—to function as more than a memorial for the fallen. At the time, the road that traveled up the hill comprised nine sloped steps (hence the name Kudan, or nine steps), and from the summit one could see as far as Tokyo Bay. As the original pathway up Kudan was narrow and steep, Ōmura planned to widen it and decrease the incline for easier travel by the military. Although they did not yet exist in Japan, he imagined horse-drawn carriages traveling along the street.3 In addition to the memorial itself, Ōmura proposed an expansive plan for the site (Figure 2) that would include a communal cemetery for those memorialized.

Ōmura’s vision became the foundation for the Yasukuni Shrine that we know today. But the shrine grounds do not include a cemetery, and Yasukuni Shrine houses only the spirits—not the physical bodies—of the fallen.4 Nonetheless, the construction project for the memorial itself commenced in mid-June of 1869. Temporary structures, which included the inner shrine, a worship hall, and two offering halls, were hurriedly completed in ten days. In the evening of June 28, the first shōkon ritual (literally a ritual to invite the spirits of the dead) took place, memorializing the spirits of 3,588 imperialist men who had fallen during the Boshin War. For five days thereafter, from June 29 to July 3, the shrine hosted festivities that featured sumo matches and fireworks. An imperial messenger paid tribute on June 29. Units of the Imperial Army took turns firing celebratory gun salutes. Visitors were treated to sacred sake.5 Until the permanent inner shrine was completed three years later, three festivals per year took place at the site.

At the time, these structures were known as the Tokyo Shōkonsha, or the “Tokyo shrine to invite in spirits of the dead,” and together they comprised the immediate predecessor to Yasukuni Shrine. Although the Kudan area quickly became a popular location, the shrine was generally absent from cultural representations of Tokyo in general and of the Kudan area in particular. The turning point was the 1872 spring festival, conducted immediately after the permanent structure was completed, during which numerous people visited the shrine grounds. An article reporting the festival in the Yūbin hōchi newspaper suggests one reason for the lack of attention in previous years:

For the past couple of years, few people visited this shrine and many had no respect for the facility, as the enshrined here were only those from the Western domains…6

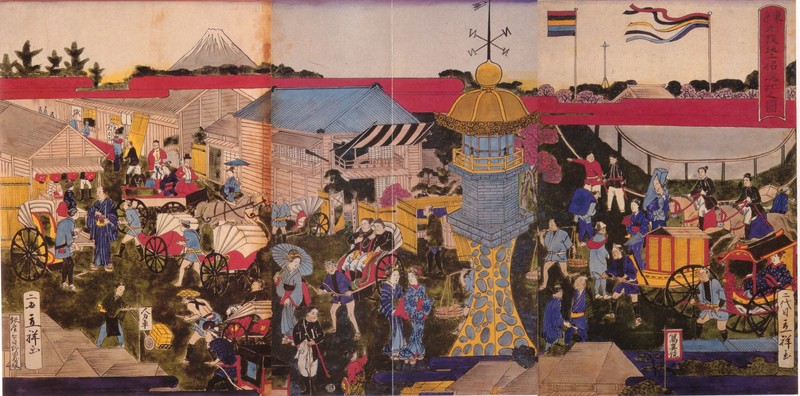

It was the new, permanent shrine that attracted Tokyoites, not the memorial function of the site. By this time, other novelties were perched atop Kudan Hill, including a pair of monumental stone lanterns completed in 1871. Together with the spectacular view of the bay, the shrine grounds inspired artists and attracted nearby residents. Festivals and other events on the shrine grounds quickly became popular.

|

|

|

| Figure 4. Inner shrine, c. 1872. | Figure 5. Risshō II, Tokyo Kudan-zaka-ue Shōkonsha no Zu, c. 1868. | Figure 6. Hiroshige III, Tokyo Meisho Zue, Shōkonsha Taka-Tōrō no Zu, c.1871. |

There was a simple reason that people living within easy traveling distance of the shrine initially had little knowledge of the men who were memorialized: the antibakufu faction, which took political power away from the Tokugawas, was led by men from Chōshū and Satsuma, the “Western domains.” Other major participants were the domains of Aki, Inshū, and Tosa, also located in the Western half of Japan. While leaders quickly took over Tokyo to organize the new government, residents were not invested in the fate of the dead of the imperial forces. Not only did the men come from the faraway “Western domains,” but ordinary Tokyoites at the time had little to do with armed conflict. Armed participation in a military cause was for the most part limited to the samurai class during the Tokugawa era. The significance of the shrine as a memorial to deaths that occurred at Ueno and other related battles was not apparent to most Tokyoites in early Meiji.

Of course, Tokyo Shōkonsha (and Yasukuni Shrine soon thereafter) did not remain an obscure institution for long, as can be observed by the prominent place it occupied in the last years of the Asia-Pacific War. The process that transformed it into a central institution of war memory, however, is not straightforward. Wars and the resulting loss of life in Japan’s imperialist quest certainly played a key role in this transformation: Death was presented in a positive light in order to sustain a level of enthusiasm to support these wars.

Imperial Japan was certainly not alone in this effort. In analyzing the modern European experience of warfare (roughly contemporaneous with my work here), George Mosse discusses what he refers to as “the Myth of the War Experience,” with a particular focus on how the concept was mobilized in post-World War I Germany.7 In representations of war memory in prose, poetry, picture books, and film, Mosse identifies a strong urge to portray a higher meaning of the war experience that was shaped by encounters with mass death and argues that this Myth of the War Experience developed more significantly in defeated nations.8 Redefining the meaning of the lives that were lost was central to this myth: War death was presented as sacrifice and resurrection rather than loss of life. Young soldiers were remembered as having fought courageously and dying for the homeland singing joyously (in striking parallel to anecdotal accounts of Japanese troops shouting “Long live the emperor!” in the face of death). Mosse contends that these narratives were influential not so much for the soldiers in the trenches but, significantly, more for those waiting at home.9

Yasukuni Shrine played an important role in the development of such myths and their transformation into a sort of national belief. Over time, and certainly by the 1940s, Yasukuni Shrine came to occupy center stage in the creation of a Japanese myth of war experience.

What was the origin of the idea that dying in war for the emperor’s sake is the greatest honor one could achieve? And who realized that this idea could be used to mobilize men for a common cause even in the face of death? “Yasukuni the belief,” of course, is an invented tradition, just like national holidays, anthems, flags, and other conventions of nationhood.10 I am interested in the origins of the myth and the ways in which they were reinvented.

The Origins of Yasukuni Practice

To address these questions, I start in the years leading up to the Restoration, when the practice of commemorating war death was normalized. Scholars such as Ōe Shinobu have provided the early history of Yasukuni Shrine.11 Yet the existing narrative does not explain the process through which the Japanese came to embrace the idea of dying for the emperor or the idea of transforming the war dead into a protector god for Japan—a process that closely aligns with the development of the Myth of the War Experience in modern Japan. Although the shōkon ritual conducted at Yasukuni was introduced during the last years of the Tokugawa era, planners of this ritual drew on precedents and customs to memorialize military deaths.

Shōkon rituals in general draw from traditional death-related practices in Japan, which developed out of the belief in the close relationship between the living and the dead. It was believed, for example, that the spirits of the dead lingered in the world of the living after death. It was commonly thought that spirits were confused about or unaccepting of their death. Rituals were designed to call back the wandering spirits to the world of the living or to attempt to communicate with the spirits, typically to placate them.12 This kind of spirit, ara-mitama (spirit of the new dead) in Buddhist terminology, was deemed capable of harming the living. Especially feared were spirits of those who were believed to have had special powers (whether psychic or political) while alive, those whose death rituals were not performed properly, and those who died an untimely death (including the military dead). Rituals were conducted in order to tame these spirits, based on the belief that, when properly appeased, the power of vengeful spirits is transformed and brings positive influence to the living. The imperial court historically followed this tradition to commemorate and posthumously promote men who had died a tragic death as a way to placate their spirits. Sugawara no Michizane (845-903) and Kusunoki Masashige (c.1294-1336) both had shrines dedicated to them.

In medieval times the fear of vengeful spirits (goryō shinkō) grew into a battlefield memorial practice. According to this practice all deaths were memorialized, whether enemy or ally.13 Victors conducted a ritual called dai segaki e (the great rite to appease hungry ghosts) for all the war dead, from both sides. Victors typically erected a memorial on the site for both enemy and ally (teki mikata kuyō-hi). This medieval practice is distinct from Yasukuni ritual in that both enemy and ally were memorialized.14 Indeed, the dead from the defeated side were memorialized with particular attentiveness.15 Previous accounts conclude that the creators of Yasukuni Shrine appropriated and politicized this traditional ritual by selectively memorializing and commemorating war death for the emperor.16

A close examination of the ways that death rituals were conducted in the years leading up to and during the Restoration suggests, however, that there was not yet an established arrangement to discriminate against enemy dead. In some of the Restoration-related battles, all dead were memorialized regardless of which side they had fought for. In other cases, concerted efforts were made to prevent the enemy from tending to their dead. But when Tokyo Shōkonsha was created, the idea of selective memorialization was not yet institutionalized. Instead, a move to politicize the war dead for a larger cause emerged during the last years of the Tokugawa era. I outline below the development of death rituals in some of the antibakufu domains and then introduce instances where death—encompassing both the physical bodies and the spirits of the dead—was mobilized for the construction of a collective identity. The idea of mobilizing death for a political cause is hardly unique to modern Japan, thus my analysis is informed by scholars who have studied the politics of memorial, burial, exhumation, and reburial elsewhere.17

Son’nō jōi and the Legend of Kusunoki Masashige

Two domains in particular hold the key to the modern practice of shōkon, which developed into the ideas behind Yasukuni Shrine: Chōshū, a key player of the Meiji Restoration and situated at the Western end of mainland Japan, and Mito, the birthplace of the Mito School of nativist thought, located much closer to Edo. During the final years of the Tokugawa era, men of samurai status in Chōshū began to collectively and publicly memorialize the deaths of samurai. Around the same time, some six hundred miles away, Mito ideologues were promoting the idea of son’nō jōi (revere the emperor; expel the barbarian) as a way to strengthen national consciousness by uniting under the emperor. Both were responding to the emerging sense of crisis precipitated by the decline of bakufu influence, social unrest generally, and the appearance of foreign ships in Japanese waters.

In the beginning the Chōshū practice was exclusively domain based. In October 1851 Chōshū leader Mōri Takachika ordered research on and the collection of the names of all samurai who died for a cause that benefited the domain. Two years later, in 1853, Chōshū men created a register of such domainal deaths, deposited it at the local Tōshunji temple, and performed a Buddhist-style memorial service on June 14. This practice was to be an annual ritual.18 While the religious style differs, this ritual bears striking resemblance to the Yasukuni practice.

The circumstances contributing to the reasons for these rituals, however, are open to interpretation. For instance, these rites became an annual event when foreign ships appeared in the waters surrounding Japan: Commodore Matthew Perry, a catalyst for Japan’s dramatic shift in foreign policy, arrived at Uraga on June 5, 1853. Domestic politics also contributed to the situation. Chōshū leaders had held the bakufu in deep contempt throughout the Tokugawa regime. According to some accounts, as an annual new year’s tradition, a retainer would ask the daimyo, “should it be this year [that we attack the Tokugawas]?” to which the daimyo would always respond, “not yet.” Retainers are said to have slept with their feet facing Edo to demonstrate their resentment.19 With the political power of the bakufu waning, Chōshū leaders began to anticipate armed conflict, with an eye to opportunities to overthrow the bakufu. At a time when more deaths could be foreseen, ritualized treatment of the dead could help promote a collective identity.

Although there are similarities between the annual Chōshū memorials and Yasukuni practice, the Chōshū rituals were conducted in the Buddhist style. How did the shift to the Shinto style of Yasukuni enshrinement take place? Further, how was the concept of fighting for the emperor incorporated into the rituals? The Mito domain produced thinkers who played a central role in shaping the political ideas behind the restoration, including son’nō jōi. The Shinron (The New Theses, 1825), by Mito scholar Aizawa Seishisai, is a key text that promotes the concept of son’nō jōi and highlights the emperor’s importance. Written as a response to the bakufu order of the same year to expel foreigners from Japanese waters, Shinron attempted to strengthen a collective national consciousness through unity under the emperor. The goal of Shinron was to secure Japanese independence by establishing a strong political structure that maintained the bakufu politically, while creating a renewed identity around the authority of the emperor. In short, it emphasized national consciousness of Japan as a whole (with both the bakufu and the court intact) over allegiance to individual domains.20 However, once the bakufu signed treaties to open Japanese ports, Son’nō jōi quickly came to include the idea of overthrowing the bakufu.

To promote a new brand of son’nō jōi that included restoring exclusive power to the emperor, Mito scholars used a fourteenth-century figure Kusunoki Masashige (c.1294-1336). Significant here were both Kusunoki’s initial role in aiding Emperor Godaigo terminate the Kamakura bakufu (1185-1333) and establish his own regime (Kenmu Restoration, 1333-1336), as well as his failure in 1336 to protect the court’s political power from Ashikaga Takauji, after which he took his own life. The Kusunoki figure proved useful for the Mito scholars’ attempts to foster a sense of nationalism focused on the emperor. Kusunoki quickly came to be revered as a hero in a historical “overthrowing of the bakufu,” and as the emperor’s loyal follower who sacrificed his life for the imperial cause.

Kusunoki also appears in Shinron, in which Aizawa Seishisai advocated the deification of people who accomplished extraordinary deeds for Japan. The connection with Shinto is also introduced here. Aizawa mentions Shinto shrines that are dedicated to people whose deeds were significant and argues that reviving the tradition of deifying loyal warriors would encourage commoners to revere the gods. One such figure was Kusunoki. In an 1834 text, Aizawa proposed gathering comrades on the anniversary of Kusunoki’s death for training and morale building.21 Here we see a communal identity beginning to develop via the death rituals.

Aizawa’s follower Maki Izumi went one step further in arguing for the deification of loyal warriors in history and their posthumous promotion. In addition, he suggests dedicating shrines to these figures as a way of inspiring contemporary warriors.22 On May 25, 1862, Maki conducted a ritual for Kusunoki during which he also memorialized eight spirits of antibakufu Satsuma warriors who died during the Teradaya Incident. Around this time, Kusunoki rituals began taking place in other domains as well. In 1865, residents of the Yamaguchi domain, for example, began regularly conducting a Kusunoki ritual and soon incorporated the dead from their own domain into the ceremony.23 Through these combined memorials, the Kusunoki legend shifted its emphasis from a narrative of successful imperial restoration to one of a brave hero who sacrificed his life for an imperial cause. His death was thus mobilized for a larger political objective: to rally around the emperor in order to unseat the Tokugawa regime from power.

Chōshū Memorial Practices

The idea of Kusunoki worship traveled to the Chōshū domain early on. In the mid-1850s, Yoshida Shōin, a scholar and son of a Chōshū samurai, preached on the heroic self-sacrifice of Kusunoki to pupils in his private school while he was under house arrest. A strong critic of the bakufu’s passive foreign policies, Shōin encouraged his students to emulate Kusunoki and defy the bakufu in order to restore power to the court. His many followers, including Takasugi Shinsaku and Kusaka Gensui, would play central roles in the movement to overthrow the bakufu.

By the early 1860s, clashes between the antibakufu and pro-bakufu factions had led to bloodshed such as the Ansei Purges (1858-1859) and the Sakurada Gate Incident (1860). Shōin was executed in October 1859 as a part of the Ansei Purges. By this time, antibakufu supporters were converging in the imperial capital to plan an overthrow of the Tokugawa regime. Chōshū leaders conspired to hold a collective memorial rite in Kyoto to commemorate their dead. But the bakufu forbade a proper memorial for these dead. From the bakufu’s viewpoint, the imperial loyalist dead were criminals who had been executed or killed as rebels. The first matters for attention, therefore, entailed obtaining a court mandate to remove their criminal status. The involvement of the emperor was also useful for the leaders of the antibakufu movement since it would emphasize the idea that the antibakufu faction was now fighting for a common cause: the restoration of imperial political power. A memorial sanctioned by the emperor offered the perfect opportunity to instill in the antibakufu supporters a sense of son’nō—reverence for the emperor—as well as a collective identity.

In 1862 Chōshū leaders successfully solicited Emperor Kōmei’s approval to posthumously exonerate men who died for antibakufu causes. On August 2 of that year, Kōmei sent the bakufu an imperial message about his plan to memorialize “deaths in state affairs (kokuji).”24 Fourteenth shogun Iemochi freed all imperial loyalist prisoners, exonerated all those who had died, and granted permission to construct graves for them. Among those exonerated was Yoshida Shōin. Chōshū men requested this ritual largely to revive the name of Shōin, their revered teacher. The event was the first memorial ritual initiated in the name of the emperor to involve multiple domains. It can be considered the key event in restoring political power in the name of the emperor through the use of death rituals.

Kōmei himself officiated at a shōkon ritual at the Reimeisha shrine at Mt. Ryōzen in Higashiyama, Kyoto, on December 24, 1862.25 For the first time, men from multiple domains were memorialized together in the name of the emperor for efforts to overthrow the bakufu.26 This transformed memorialization into a tool for constructing a collective identity. The ritual not only relieved the men of their criminal status, but made them heroes who had sacrificed their lives for the imperial cause. In the following year, 1863, for the first time in Kyoto a physical structure was built exclusively for the shōkon ritual. Men from the Tsuwano domain constructed a small shrine inside the Yasaka Shrine grounds, situated at the foot of Ryōzen, where, on July 25, they memorialized forty-six men. Immediately after the ritual, the shrine was relocated to the residence of Tsuwano leader Fukuba Bisei to conceal the event from pro-bakufu forces. In 1931 the structure was transferred again to Yasukuni Shrine where it exists on the grounds as the Motomiya, or original shrine.27

Chōshū rituals took on a Shinto quality once the move toward Restoration began. On May 25, 1864, members conducted a memorial at the Shiraishi residence, where the kiheitai (volunteer army comprised primarily of commoners which played a significant role in the Restoration) would soon be established. Loyalists from the Chōshū domain were in attendance along with Maki Izumi, the Kusunoki admirer and son’nō jōi advocate from Mito. For the first time for the Chōshū men, the rituals were conducted in the Shinto style. For the first time the Chōshū idea of regularly memorializing dead comrades merged with the Mito idea of commemorating commendable deaths as gods in the Shinto tradition—and offering prayers for military success.

Back in their home domain, Chōshū also led the creation of physical structures for the rituals. In August 1865 Chōshū constructed a shrine at a site in Sakurayama (Shimonoseki), where memorial rituals continued to be held on a regular basis. A permanent structure for the rituals would be useful not only for regular events but also as a visible marker, a constant reminder for the men of the importance of their political cause. The previous month a law had been passed that required each county to build its own shōkonsha, or shrine for conducting memorial rituals.28 Unlike Yasukuni Shrine, gravelike stones with the names of the deceased now neatly stand behind the shrine. The bodies, however, were cremated and the ashes buried at temples or battlefields. The stones are markers to which the spirits of the dead were to return.

Figure 7. Memorial markers at Sakurayama Shrine. Figure 7. Memorial markers at Sakurayama Shrine. |

The Chōshū shrines were also educational. At the time of the Restoration, many lower-ranked members of domains that were fighting on behalf of the emperor knew little about him. Moreover, the unification of the nation under the emperor’s name was still a new idea. Some lacked access to even a part of the education that a child of a samurai received. In fact, in August 1863, in the midst of attacks by foreign battleships at Shimonoseki, Chōshū member Takasugi Shinsaku created the kiheitai, which enabled commoners to fight. To those fighting for the emperor and risking their lives, just as their deceased comrades had done, the memorial practice and physical presence of the shōkonsha buildings reinforced the message of an imperial cause. An iteration of Aizawa’s 1834 proposal to annually commemorate Kusunoki’s death is evident here: Men concluded their shōkon ceremonies by pledging to follow in the footsteps of their slain comrades.29 In this sense, a shōkonsha was not merely a memorial site but also a place to which men pledged to return as spirits. Commoners were conscripted to construct the local shōkonsha.

The regular rituals also normalized two conditions that had recently been introduced along with the shōkon rituals: first, the idea that the domain, rather than the family member of the deceased, had authority over the memorialization process, and second, the attenuated distinction between shrines dedicated to gods and those dedicated to human spirits.30 The domain’s authority over memorialization of the dead transferred the right to perform death rituals from the private entity of the family to a public one of the domain. This established the precedent for the Japanese state’s control over the memorialization of the war dead.

Architects of the new government, comprised primarily of Chōshū men, developed this domain-based practice into a national one. In May 1868 the newly instituted government built a shōkonsha on Ryōzen to collectively commemorate imperial loyalists who had lost their lives in political struggles since 1853, as well as the soldiers of the Imperial Army killed at Toba-Fushimi, the first battle of the Boshin War.31 The Kyoto facility housed the graves of representative loyalist dead as well as several domain-specific shrines and was considered a central facility at the time. However, the practice of collective memorial was not limited to this site. For example, on June 2, 1868, less than two months after the bakufu relinquished Edo Castle, to collectively commemorate all deaths in the Imperial Army, the governor general of the Eastern Expedition Group (Tōseigun) held a large-scaled shōkon ceremony at Edo Castle rather than the newly constructed Higashiyama Shōkonsha. The ceremony was conducted in the very hall where negotiations to hand over the castle were held by the last shogun, Yoshinobu, thus highlighting the redemptive symbolism of the event: that the transfer of power occurred as a result of the lives lost. The official chronicle of Yasukuni Shrine points to this ritual as the beginning of the Tokyo Shōkonsha.32

On July 17, 1868, Tokyo was designated the new capital. With the official relocation of Emperor Meiji from Kyoto to Tokyo in March 1869, the new government decided to construct a shōkonsha in Tokyo to replace the one in Higashiyama.

Who Can Be Enshrined?

Chronologically, we have arrived at the moment when Ōmura Masujirō selected the site at Kudan. But there is one other important issue surrounding a characteristic of the shōkon practice at Yasukuni Shrine that needs to be addressed: the problem of selective memorialization. One major criticism of Yasukuni Shrine in recent decades is that it commemorates only particular kinds of deaths: mostly Japanese military deaths that resulted from wars of imperialism and loyalist deaths that occurred during the Restoration. This kind of selective memorialization has had further ramifications in the post-Asia-Pacific War period. Many bereaved family members have submitted requests to Yasukuni Shrine to have their loved ones enshrined, whereas others have demanded the removal of names from the shrine’s register.33 The process of post-1945 memorialization includes the compilation of the names and other information about the deceased, which was often provided by the Japanese state.34 Although the head priest always makes the final decision in special or controversial cases, for example, the Class-A war criminals, a set of guidelines also helps determine the names for enshrinement. These guidelines have changed numerous times, even after 1945, sometimes resulting in enshrinement of those who had died decades earlier.35

The popular theory that antibakufu men started selective memorialization for political purposes during the restoration-related battles, may not be entirely accurate. Late Tokugawa memorial practices did become increasingly political, but there were no predetermined qualifications that the deceased had to meet in order to be memorialized in a particular ritual. In fact, at times all of the deaths on both the imperial and the bakufu sides were memorialized, as with the memorial that was ordered by the court and performed in October 1864 at Chion-in, a Pure Land temple in Kyoto.36 Moreover, during the Boshin War, imperial loyalists often allowed the enemy dead to be memorialized. For example, imperial troops immediately consented to the burial and memorial of the pro-bakufu fighters who died in the Battle of Echigo-Koide in April 1868.

Political Use of Death: Dead Bodies and Memorial Practices

The idea to establish eligibility for memorialization and to use the practice of memorializing for political purposes developed gradually. At the outset, efforts were not focused exclusively on the spirits of the dead—the practice of Yasukuni Shrine—but on death rites in general, including proper burial of the bodies. And in later years, during Japan’s wars of imperialism, the military took full control of not only the spirits of the war dead (through Yasukuni Shrine) but also their bodies as a way to exert power over those still alive.

Being under the jurisdiction of the military, it is not surprising that Yasukuni Shrine became a venue through which the military organized its dead. Particularly in the final years of the Asia-Pacific War, when retrieval of bodies from the front was nearly impossible, mobilizing the spirits of the war dead became a useful replacement for rituals associated with bodies and ashes. Memorial rituals at Yasukuni Shrine were only one component of a variety of practices that utilized death to promote militaristic nationalism.

As we have seen in the discussion of the 1862 process of rehabilitating the posthumous status of men who were considered antibakufu, criminals and traitors (kokuzoku) were not eligible for typical death-related rites in Tokugawa Japan. On October 27, 1859, Yoshida Shōin was beheaded in an Edo prison and thrown into a hole in the ground along with other executed criminals. On January 1, 1863, upon receiving permission from the bakufu, Shōin’s remains were dug up and transported from the mass burial ground to open land in Tokyo that Chōshū owned. According to some accounts, the procession barged onto a Ueno bridge that was reserved exclusively for use by the shogun, viciously attacked the guards, and crossed the bridge. In 1882, followers constructed a Shinto shrine by the gravestone, thus elevating Shōin to the status of a god.

Shōin’s spirit was memorialized in an official ritual carried out by the emperor in Kyoto, thus signifying that the death was for an imperial cause. The Kyoto ritual and the Tokyo spectacle together signified the determination of the Chōshū men to pursue the process of jōi in the name of the emperor—an action that Shōin himself had advocated. The rituals associated with Shōin’s death were not conducted exclusively for the dead, for example placating the potentially angry spirit of Shōin, but were transformed into practices that created new meanings for the living, both enemy and ally.

Other instances occurred during the restoration, when practices associated with death, burial, and memorial were highly politicized: the battle of Aizu. A number of mass suicides took place during the battle. During and after the battle, the imperial troops—led by Chōshū—forbade the burial of Aizu dead. Dead Aizu bodies were left to rot on open fields, and local residents subsequently struggled for their proper burial. If Shōin’s example presents a case study in posthumous restoration of honor through rituals involving the body and the spirit, incidents that occurred during the battle of Aizu demonstrate the power to control people by denying proper burial and memorialization of their dead. The two incidents provide a strong rationale for politicizing memorial practices, which took place alongside the development of criteria for enshrinement at Yasukuni Shrine.

On June 4, 1879, Grand Minister Sanjō Sanetomi issued a directive that announced the renaming of Tokyo Shōkonsha as Yasukuni Shrine and designating it as a Special Government Shrine (bekkaku kanpeisha).37 This designation of the memorial as a Shinto shrine completes the first period in the history of Yasukuni Shrine. With the designation, the rituals and physical structures associated with the use of the war dead for political purposes were institutionalized. At the same time, the spirits of those enshrined became a permanent fixture in the shrine itself. In succeeding decades, Yasukuni Shrine increased its official capacity as Japan’s national military memorial, its visibility reaching its zenith in the last years of the Asia-Pacific War.

This article was adapted from Chapter 1 of Yasukuni Shrine: History, Memory, and Japan’s Unending Postwar. I thank the University of Hawaii Press for generous permission to publish this material here.

Recommended citation: Akiko Takenaka, “Mobilizing Death in Imperial Japan: War and the Origins of the Myth of Yasukuni”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 38, No. 1, September 21, 2015.

[Ed. Note: an earlier version of this article misidentified the Prime Minister who visited Yasukuni in the postwar as Suzuki Kantarō instead of Suzuki Zenkō.]

Related articles

• James Shields, Revisioning a Japanese Spiritual Recovery through Manga: Yasukuni and the Aesthetics and Ideology of Kobayashi Yoshinori’s “Gomanism”

• John Breen, Popes, Bishops and War Criminals: reflections on Catholics and Yasukuni in post-war Japan

• John Junkerman, Li Ying’s “Yasukuni”: The Controversy Continues

• Akiko Takenaka, Enshrinement Politics: War Dead and War Criminals at Yasukuni Shrine

• Takahashi Tetsuya, Yasukuni Shrine at the Heart of Japan’s National Debate: History, Memory, Denial

• Takahashi Tetsuya, The National Politics of the Yasukuni Shrine

• Mark Selden, Nationalism, Historical Memory and Contemporary Conflicts in the Asia Pacific: the Yasukuni Phenomenon, Japan, and the United States

• Matthew Penney, Nationalism and Anti-Americanism in Japan – Manga Wars, Aso, Tamogami, and Progressive Alternatives

• John Breen, Yasukuni Shrine: Ritual and Memory

• Yomiuri Shimbun and Asahi Shimbun, Yasukuni Shrine, Nationalism and Japan’s International Relations

• Andrew M. McGreevy, Arlington National Cemetery and Yasukuni Jinja: History, Memory, and the Sacred

Notes

1 Kido Takayoshi, The Diary of Kido Takayoshi, vol. 1. (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1983), 184-5.

2 Ikeda Ryōhachi, “Yasukuni Jinja no sōsetsu.” Shintō shi kenkyū 15 (1967): 50–70. Archival documents associated with the construction of Tokyo Shōkonsha are available in Yasukuni Jinja hyakunenshi. Vol 1. (Tokyo: Yasukuni Jinja, 1983).

3 Recollection of Kamo Mizuho, the second head priest of Yasukuni Shrine. Cited in Murata Minejirō, Ōmura Masujirō sensei jiseki (Tokyo, 1919).

4 Diary entry dated June 26, 1869. Kido, 248-249.

5 Details of this first festival are included in Ikeda, 56-58.

6 Yūbin hōchi shinbun (monthly), June 1872, italics added. The event that took place in May was reported in June since this was the newspaper’s first edition.

7 George L. Mosse, Fallen Soldiers: Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

8 Ibid., 5-7.

9 Ibid., 70-73.

10 Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, eds, The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983); Takashi Fujitani, Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

11 Representative scholarship on Yasukuni Shrine that includes a summary of its early history includes Murakami Shigeyoshi, Irei to shōkon: Yasukuni no shisō. (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1974), Ōe Shinobu, Yasukuni Jinja. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1984), and Akazawa Shirō, Yasukuni Jinja: Semegi au “senbotsusha tsuitō” no yukue (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 2005). A summary in English is available in Breen, “Introduction,” in John Breen ed. Yasukuni, the War Dead, and the Struggle for Japan’s Past (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 1-21. Most recent works draw upon Murakami and Ōe for the shrine’s early history.

12 Namihira Emiko, Nihonjin no shi no katachi: Dentō girei kara Yasukuni made (Tokyo: Asahi shinbunsha, 2004), 77-9.

13 Nishimura Akira, Sengo Nihon to sensō shisha irei: Shizume to furui no dainamizumu (Tokyo: Yūshisha, 2006), 56-7.

14 Tsuda Tsutomu, “Bakumatsu Chōshū han ni okeru shōkonsha no hassei,” Jinja Honchō Kyōgaku Kenkyūjo kiyō 7 (2002): 127–169.

15 Ōe, 120-122. See, also, Murakami.

16 Ōe references a work by ethnographer Sakurai Tokutarō, Reikon kan no keifu to make this point. Ōe, 119-21.

17 For studies on the political use of the dead outside Japan, see for example, Katherine Verdery, The Political Lives of Dead Bodies: Reburial and Postsocialist Change (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), István Rév, Retroactive Justice: Prehistory of Post-Communism (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005), and Pamela Ballinger, History in Exile: Memory and Identity at the Border of the Balkans (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003). Heonik Kwon, “The Korean Mass Graves,” The Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, posted on August 1, 2008.

18 Nihon Shiseki Kyōkai, ed., Kōhon mori no shigeri. 2 vols. Reprint. (Tokyo: Tōkyō Daigaku shuppankai, 1916, 1981).

19 Ichisaka Tarō, Bakumatsu eiketsu tachi no hīrō: Yasukuni zenshi (Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, 2008), 59.

20 For a close analysis of the text, see Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi, Anti-Foreignism and Western Learning in Early Modern Japan: The New Theses of 1825 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986), and Harry Harootunian, Toward Restoration: The Growth of Political Consciousness in Tokugawa Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970).

21 Kobayashi Kenzō, and Terunuma Yoshifumi, Shōkonsha seiritsu no kenkyū. Tokyo: Kinseisha, 1969), 40-43.

22 Ibid., 45-47.

23 Ibid., 48.

24 An excerpt of the relevant section of this imperial order is available in Kobayashi and Terunuma, 30-31.

25 Reimeisha was a shrine founded in 1823 for the purpose of funerals (Kobayashi and Terunuma, 55-6). For a detailed account of this memorial service, including names of attendees and the prayer offered during the ritual, see Katō Takahisa, “Shōkonsha no genryū,” Shintō-shi kenkyū 15 (1967), 9-27.

26 The men were later enshrined at Yasukuni around 1889. Kobayashi and Terunuma, 31.

27 Tsuda.

28 Shūtei bōchō kaitenshi 7. Cited in Ichisaka, 128-9.

29 Ōkawa Ichirō, “Yasukuni mondai no shin dōkō,” Rekishi hyōron 358 (1980), 77-84.

30 Tsuda, 144.

31 Murakami, 19-22.

32 Hata Ikuhiko, Yasukuni Jinja no saishin tachi (Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 2010), 25.

33 For example, family members of medical students killed by the atomic bomb while studying at Nagasaki Medical University requested the enshrinement of their sons. Nishimura Akira, “Shi shite nao dōinchū no gakuto tachi: Hibaku Nagasaki Ikadai-sei no irei to Yasukui gōshi,” Nishi Nihon shūkyōgaku zasshi 25 (2003), 1-12. In the book, I also discuss the case of Okinawans, Koreans, and Taiwanese, who have demanded enshrinement.

34 I detail this process in chapter 5 of my book.

35 Hata.

36 Kobayashi and Terunuma, 34.

37 The designation Special Government Shrine was an early Meiji invention, elevating the status of shrines dedicated to persons who loyally served the emperor in one way or another.