Essential Ingredients of Truth: Soldiers’ Diaries in the Asia Pacific War

Aaron William Moore

All swindlers on the earth are nothing to the self-swindlers.

-Charles Dickens

In the last decade, numerous film and print media treatments of the Second World War have focused on the “soldier’s perspective.” Because the wartime generation is now rapidly disappearing, postwar generations have become especially eager to know the war. In particular, there is a hunger to learn how it was experienced by ordinary servicemen—a focus popularized most effectively by historian John Keegan (and film directors such as Clint Eastwood, Oliver Stone, and Francis Ford Coppola). Scholars and war history buffs alike seek “reliable” accounts of the war; presumably, the best histories of the war are those that rest on a firm foundation of the most “reliable” sources. Certainly, the larger historical narrative of the war is incomplete without adequate attention to the personal records that servicemen kept at the time, such as diaries and letters. Nevertheless, like any document, it is essential to pay close attention to the assumptions shared by the authors of these documents and their audiences today, especially regarding the “truth” such texts putatively contain. Invariably, issues of self-discipline, including self-censorship, as well as military discipline and direct external censorship, intrude.

Diary writing in

Meanwhile, new technologies of reproduction such as telegraphy, photography, and mimeography and the rise of the mass circulation newspaper and magazine fed growing domestic demand for information about

In addition to commanding a knowledge of the “facts” (weather, unit position, terrain, etc.), authenticity was also closely tied to narrating one’s personal experience of war. Officers who had served in the Japanese army even printed their diaries, which sold extremely well in the Japanese market, particularly after the Russo-Japanese War in 1905. Tamon Jiro’s field diary, published in 1912 as My Participation in the Russo-Japanese War (Yo no sanka shitaru Nichiro sen’eki), along with Sakurai Tadatoshi’s iconic Human Bullets (Nikudan), was extremely popular. Tamon claimed that he made the diary public in order to answer frequent questions from inexperienced recruits such as “What happens during war? What actions do lower echelon officers take during battle? What do you think about (kannen) during a battle?” He believed that it would be helpful for “young cadets with no experience of war” and that it would provide material for “readers’ future self-cultivation” (dokusha shorai shuyo). [3] Of course, Tamon was aware that his “diary” was to be published, and the possibility of censorship and punishment in Imperial Japan was an ever-present factor when writing a military diary (whether it be subject to review or not). Nevertheless, as will be shown below, the desire to produce a “true” image of oneself was at least as strong, if not stronger, than the often self-contradictory messages sent down by the state, military, and mass media. In fact, merely reproducing acceptable propaganda might make writing a diary unsatisfying. Early on in Japanese modern discourse, the “factual” or “truthful” replication of experience in diary format established the truth value of these texts, as well as tying it to the concept of self-discipline, so spinning any lie authorities might want to hear devalued the diary itself—unless, of course, the author agreed with those views.

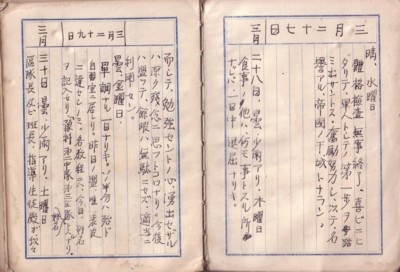

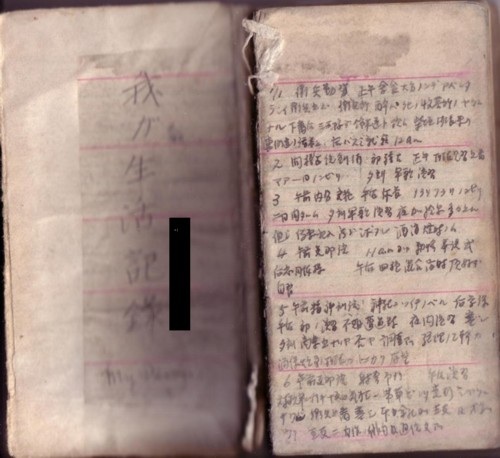

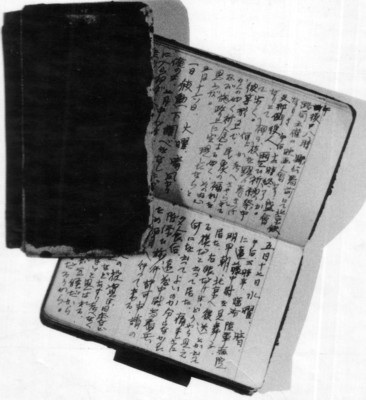

Diary, “A Record of My Life” (

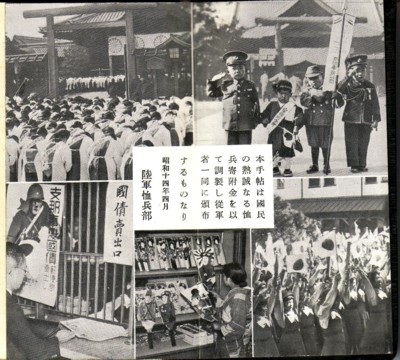

With the rise of mass politics in

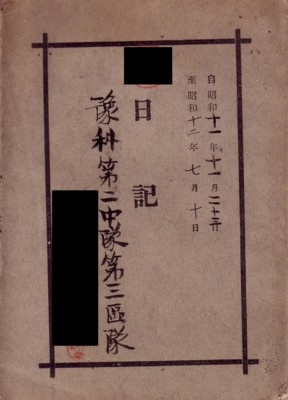

Inside cover of a war diary mass produced for servicemen during the 1940

What constitutes “truth,” however, has always been difficult for servicemen in wartime, and it was no less so for some veterans in the postwar era. Japanese captives of the Chinese Nationalists were enrolled in reeducation programs, particularly in “

For the first time, I thought about this term “brainwashing.” Then, I realized afterwards that I had been “brainwashed” from childhood by Japanese militarism, and, because of that, I had committed atrocities. For me, my studies, self-criticisms, and acknowledgment of crimes [in

However eloquent these “returnees” might have been, postwar Japanese society was, for the most part, unwilling to listen; an early attempt to record the “confessions” of these veterans, run through as they were with the language of the Chinese Communists, was largely dismissed by the Japanese media as a fraud. [7] Despite intense social pressure, these “returnee” veterans refused to abandon what they believed to be the “truth”—just as veterans with more positive views of the war did, as well. [8] Even if one were to accept the argument that postwar accounts might lack the essential reliability to be used as historical sources, can one really accept that some deeper “truth” would be revealed in the wartime documents? When reading wartime and postwar documents, opposing, contradictory, and highly individualized views of “the truth” inevitably emerge.

In looking at personal diaries from the Second World War (1937-1945), one of the most important facts to be confronted is the widespread support for the war effort. At the same time, Japanese wartime diaries convey a strong sense that, for many servicemen, discovering truth, writing truth, and even “embodying truth” was a major preoccupation. Particularly on the home front, these two goals were not necessarily mutually exclusive. In 1937, a few days after receiving his notice to serve, Kimura Genzaemon, a schoolteacher from

6am lecture from the squad commander. Dreams of the battlefield and running about the barracks. Every night my dreams are not about my home, not about my wife and children, but actually an image of myself on the battlefield. The most beautiful thing in the world is “truth,” an “image of one who seeks truth,” a “process toward truth.” If there is anything beautiful about war, it is that “truth” that only war can possess.

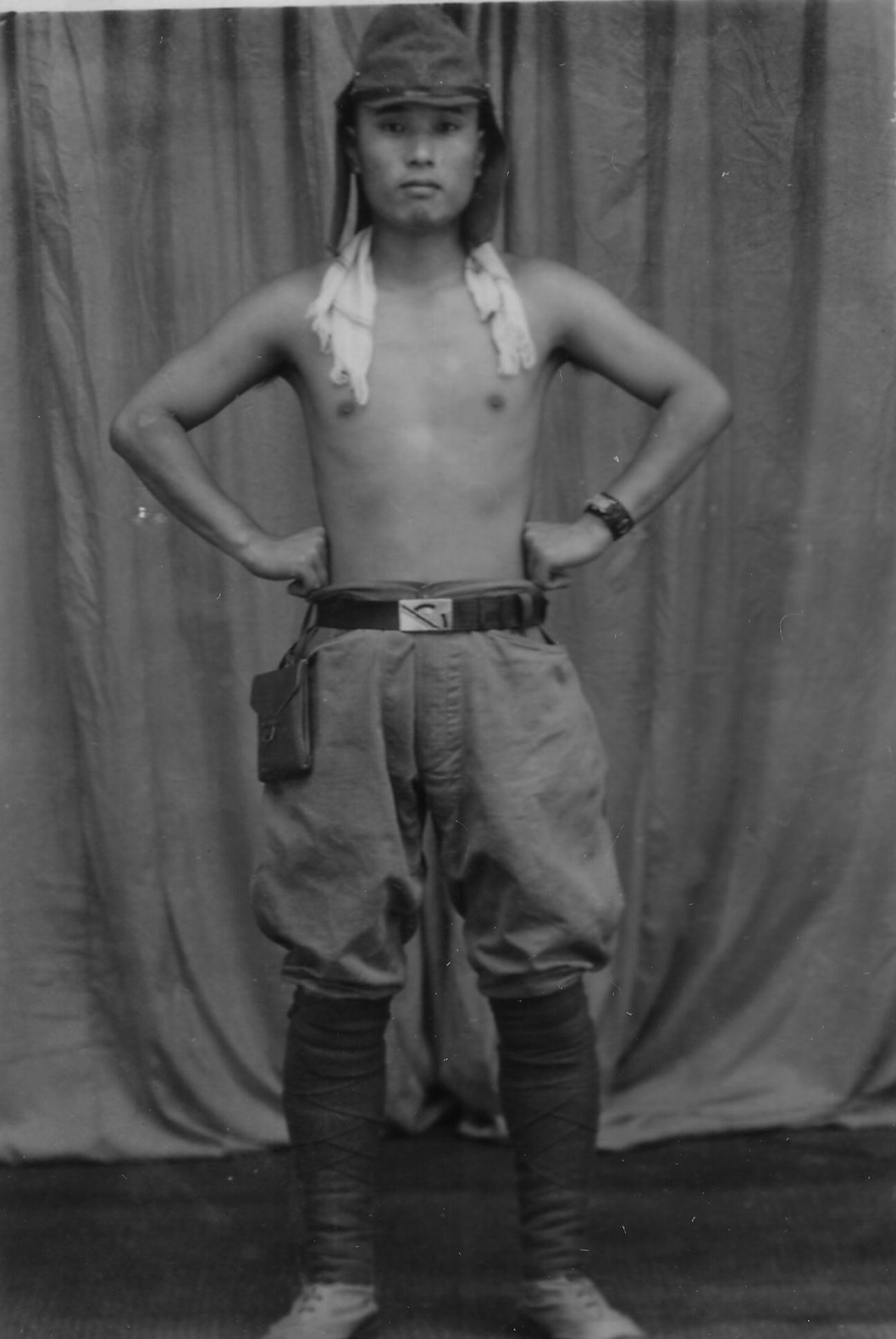

Japanese soldier in Burma

Kimura reflected on what the war meant to him, and why he was participating in it as a soldier. Then, Kimura’s diary transformed briefly into an extended farewell letter to his wife and children—whom he had to leave behind. If he could only embody a life of “truth,” he wrote, even if he was “covered in blood and tortured by all the pains of this earth,” he could face his children after the war. [9] After enduring the brutal privations of the war in Northern China, however, what began as an intellectual concept became more tightly tied to physical self-discipline. In the bombed-out city of Zhengding (in Hebei province), Kimura revisited his concern for “truth,” but was concerned with “bodily health”—that which springs naturally from a cool, clear spirit, the abnegation of indulgences, vegetarianism, and “self-caution” (Jp. jikai, Ch. zijie, watching one’s own behavior and correcting faults). Kimura’s complex (and often idiosyncratic) views on truth were tied to his belief in self-discipline, which places his text not only within the conventional view of the war, but also within the discourse on self-discipline in modern Japan altogether.

Because one’s version of the truth could be highly individualized, however, servicemen often came to radically different conclusions about war and self in their diaries. The emergence of the Special Attack Forces (tokkotai, popularly known as “kamikaze”), for example, could be very divisive. A Japanese officer in the

Unfortunately, what some diarists might consider “truth” in many ways appear to outside readers as narcissism and self-delusion. When Japanese servicemen encountered inhabitants of their expanding empire in the Pacific, they were often struck by how compliant these subjects seemed to be, and how lavishly white colonizers had been able to live. Thus, in places like occupied Dutch Indonesia, servicemen found government propaganda to be a compelling vision of their new role as liberators of Asian people in the Pacific. “Hara Kinosuke,” an elite pilot who had participated in the bombing of

We visited the homes of the local civilians (ryomin) and were treated to coffee. They have some trust in us. They are proud to receive us graciously (taigu suru), and we also find them very cute (kawaigatte iru). Teaching them Japanese is a struggle, but they are very serious, so they pick it up quickly […] The islanders are all filled with new hope, and can be seen everywhere working their hearts out. People are really simple and pure (jun). They do have that trait, unique to the people of the

Undoubtedly, this was a refreshing change from dealing with the resistance in central

The houses of the Chinese are flying our Imperial flag with signs that say “Welcome Japan!” The refugees from

Throughout the Pacific, confidence in Japanese military prowess ran high in the early months of 1942 as the British, Dutch, French, and Americans collapsed or were routed and Asian populations were “liberated.”

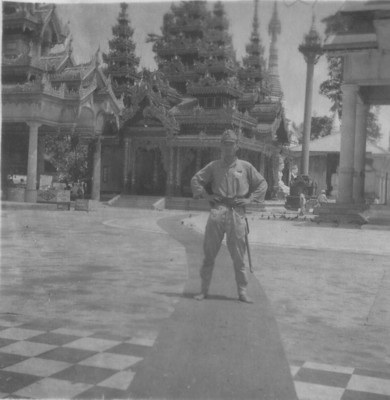

Japanese serviceman poses for a victory photograph in Burma (Personal Collection)

Watanabe boasted that they captured so many weapons, automobiles, and ammunition from the Dutch that they “are concerned with what to do with it all.” In

Since we launched our surprise landing against the Dutch, we’ve crossed 100 ri in 13 days. A truly rapid advance, our entry into the final target of

Even the dire news of a surprise American attack at

Japanese servicemen frequently used their diaries as a space for “self-mobilization:” encouraging themselves to be brave, castigating their lack of initiative, or even demanding that they prepare to make the “ultimate sacrifice.” Obara Fukuzo mobilized himself right up to the end, even re-writing his entire diary in the middle of the thick jungles of

Now we must live the lessons (senkun) of ‘Saipan’ and ‘

While rewriting this diary, however, he still could not completely obfuscate the instability of his personal narrative. Previously pliant colonial subjects began to drag their feet. “Filipino bastards,” Obara cursed, “Forgetting all gratitude (shigi) for the gift of independence, they yearn only for the soft pleasures of American-style hedonism!” His increasingly strident tone—anger at the unwilling colonial subjects, suffering over the loss of his comrades, pain from severe athletes foot, hunger and constant strafing by US Grumman fighters—only made the power he exercised over these experiences through narrative seem more brittle. Was Obara’s increasingly inflexible tone overcompensation for his fear, anger and anxiety? Why else would he feel so compelled to rewrite his entire wartime experience in such a patriotic idiom? [15] In an environment where death was nearly assured, censorship was not Obara’s concern, and yet he embraced patriotic discourse for his self-narrative—evidently by choice. No one required Obara to keep this record.

The diary served as a “factual record” for servicemen that many referred to later; they re-read their personal records in order to draw conclusions about themselves, the enemy, and their worldview in general. One striking similarity between diarists from all nations is the authors’ desire to chronicle even the most horrifying scenes and then meditate on their meaning. Even Kimura, who was an otherwise cool and level-headed diarist, could not bear the sight of the carnage in war-torn

We pull out to the edge of the city gates and spend the evening there. Chinese dead are piled up on the city walls—I cover my eyes. The city is full of corpses, and I am overwhelmed by its ghastliness (sakimi ni semaru). […] They say

In the face of such a mind-numbing sight, Kimura still struggled to find truth—his lack of “awakening” while meditating on this terrifying vision profoundly disturbed him. Many Japanese who survived the first landings at

I feel like I’m still on the boat—rocking and swaying. Everywhere you look, the place is brutally torn apart from air raids. I’m finally able to truly understand the worth (kachi) of war. This is how you know how horrible, how savage a thing it is (makurumono). Right where were we resting, under the shade of a tree, were soldiers who had just come back from an intense battle; I was filled with a sense of fortune and gratitude for having landed safely on this land, taken by the blood and tears of the marines and forward land units. I offered a small prayer to the spirits of the war dead and, facing towards the Emperor in the far, far East, while feeling how grateful I am for my country

Personal failure was another subject of deep reflection. Corporal Hamazaki Tomizo lost his sword right before the attack on

I have no face to show my superiors or the men; there’s no excuse for losing a weapon necessary for battle, and nothing can be done about it, but seppuku is even more unfilial (fuchu) at this time. How can I fight without a weapon? After losing my sword, I should die on the frontline. No matter what method you use, a fatal wound cannot be cleansed […]

Hamazaki did “cleanse” himself of the wound of humiliation, however, by using his diary as a space for self-mobilization: “I won’t be taken by this [mistake] and let it darken my heart; I’ll use my error as a basis for preparing for the next battle.” As the battle to surround

The highly individuated nature of “truth” could also manifest itself when diarists attempted to explain their actions and those of others. Months of bitter Chinese resistance following the Japanese landing at Shanghai generated great anger among the servicemen who entered Nanjing in December, 1937: “Ouchi Toshimichi” listened to horror stories of the battlefield and reflected, “The Chinese army has become really despicable (nikurashiku) to me; I want us to wipe them out (senmetsu) as quickly as possible.” [19] Others became disgusted by war and even their own “comrades.” After the initial fighting, some Chinese Nationalist forces withdrew without collecting their wounded and dead. The Chinese dead lay scattered amidst Japanese casualties in trenches and in the fields. As the Japanese advanced, Umeda described the scene:

While looking for other Japanese in the trenches, I came across wounded Chinese soldiers (fusho shita teki-san). Shocked, I led them to the unit commander. It was pitiable to see them undergo various inquisitions (torishirabe). So this is war, I thought, but an hour later they finished the investigation and were led to the rear by Lieutenant Yamane. They were probably killed. Even though they’re our enemies, they’re human beings with a soul like all other living things in this world. To use them as helpless tests for one’s sword is truly cruel. There’s no place as cruel and unjust as the battlefield. [20]

Most Japanese servicemen, however, found some space for themselves between being the willing perpetrators of war atrocities and those who learned to despise all war. Medical Officer “Taniguchi Kazuo,” who initially strongly justified

Just in case one might think that these texts reveal some inherently “Japanese” preoccupation with truth and personal record keeping, I should note that similar trends can be found in the wartime diaries and letters of Chinese, American, and Soviet servicemen as well. Many American servicemen, for example, had little love for the army or their commanding officers. Staff Sergeant Bernard Hopkins raged at the citations given to ignorant officers while the heroism of noncommissioned officers was ignored. He wrote, “I think my blood will boil when I hear of Generals and Colonels being cited.” During the Japanese invasion, the complacency and impotence of US commanding officers on the

The war plans called for this area to be held—but the local big-wigs—plenty of them asleep on the matter and few of them knowing anything of the area. I’ve been there—felt that it would take the Jap 6 months to get in there. Well, the Japs got into the area in less than a month. These same big-wigs didn’t know there was a sugar cane railroad up into the area. […] [The map] has been on file here (in HD Hq) for over two years now. I certainly hope someone gets wise soon, before the Japs start pelting us with 8” guns from over here … [22]

Many Chinese Nationalist officers recognized their faults and struggled to correct them; they used their diaries as a space to complain, worry, and propose solutions to problems whose consequence could include death. Division Commander Liu Jiaqi took self-discipline very seriously, and railed against those who did not meet his standards:

The officers and men in this division are not making any effort in building our outer defenses, and more than a few cannot follow the regulations. I am deeply concerned about this. I’m good at cultivating a spirit of meticulousness during a period of peace, but once we get our orders, it is not such an easy thing to do. From here on out, regarding our fighting spirit, if we are not resolved to die in battle, it is going to be extremely difficult to achieve victory. The officers and men in the division are spineless (weimi jingshen), our system of punishment and reward is unclear, so I’m truly concerned about our battle against the Japanese. [23]

Servicemen around the world recorded not only “facts” about the war or the army, but also about themselves. In the Red Army, where the gaze of the commissar was supposed eradicate all privacy, Soviet servicemen too used their diaries as a place to gripe, record the “true war,” and ponder revelations about themselves. Red Army translator Vladimir Stezhenskii, for example, frequently complained about being drafted into the army and pined for his girlfriend, Nina. He further worried desperately about his close friends being sent to fight the Germans in the bloody battles of late 1941 and early 1942:

I thought a lot about Arthur. For a long time now I have not believed that he was “evacuated” to the Bashkir farms (sovkoz), and, lo and behold, Ninka has written me that he went into a combat battalion. […] In the first month of the war—when the first sound one heard after the night passed was a bomb exploding—Arthur said, “You alive, old man?” “Yeah, I’m alive.” Yeah, that’s what we said. My whole life, all of my happiness, sorrow, and misfortune, my friends were with me; at all times, during difficult moments, I had friendly support and essential, intelligent counsel. [24]

The dedication to keeping an accurate account of thoughts, conditions, events, and revelations when facing death was something servicemen around the world would have recognized. One should not presume, of course, that these diaries contain the “whole truth” regarding the events they describe, but what text could possibly do this?

Indeed, like Stezhenskii, many Japanese diarists saw articulations of the self to be one of the most valuable forms of “truth.” Servicemen juxtaposed or embedded these “reflections” within the delineation of battlefield experience, where they derived their authenticity as warriors. “Yamamoto Kenji,” a private who fought in

I’ve leapt into canal beds, into the enemy camp, and stabbed Chinese soldiers to death. I’ve shot Chinese soldiers when they came to attack us at night, too. Also, while thirstily drinking soup made from chestnut husks, hungrily chewing raw garlic and daikon, I shot the Chinese at close range as they fled. If I went on about the fighting and such, well, there’s a lot of interesting stuff (omoshiroi koto) to tell, but, in order to maintain military discipline (gunki no hochi), they won’t let me write about it. [25]

“Sakaguchi Jiro,” a veteran soldier from both the Manchurian Incident and the battles of

I want to stop living in holes in the ground and go home [even if] temporarily. Another victorious spring here at the Holy War, and, looking back, I think our work is pretty impressive. This just confirms the fact that our task is to carry out punitive expeditions and work hard to build northern

The diary, then, became a space where record of fact and record of self became bound up in the same discourse; the concomitant assumptions, including the idea that a diary can somehow capture “truth,” created a possibility (for better or for worse) for servicemen to speak authoritatively about who they “really” were. When Kimura nonchalantly mused on the nature of war, self, and gambling, he perhaps unwittingly revealed the man that he created through his war diary:

In all competition (shobugoto), in order to feel a fleeting sense of superiority when victorious, one must gamble against the danger that, when defeated, one feels remorse and regret, as if one is doomed—and that is what war is like. […] Therefore, only those who stink of vulgarity will engage in competition. In other words, competition is something only mankind does, as a game. […] If this is some bellicose nature (sotosei) inherited from our primitive past (yasei jidai), then no one is quite as primitive as he who is obsessed with competition. But, within this competition, there is an opportunity one should take to perfect oneself (mizukara wo migaku beki kien).

Even when he grew frustrated with his prolonged stay in

River crossing in Burma

A diary contains whatever “truth” its author believes to be relevant to the story he is telling about himself. Sometimes, the story is heroic, but other times it is gruesome and even incomprehensible. More often than not, the voice one discovers in a wartime diary changes dramatically from one page to the next. Rather than viewing a diary as a window to truth (indeed, as servicemen themselves arguably saw it), scholars should consider the ways in which diarists used the text as a tool for defining who they were, regardless of whether the story they told about themselves was “true” or not. Like psychoanalysis, perhaps, the truth value of the tale is less important than its ability to impress consistency across the chaos that otherwise characterizes the daily experience of identity. Any other less organized self-narrative might be taken as a form of madness.

Support for the research included in this article came from the Ito Foundation, the Whiting Foundation, and the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at

Notes:

Names that I have introduced in quotes are pseudonyms. I have been asked to use them in order to protect the privacy of the diarists and their families. I have used black bars wherever images reveal personal names or other private information.

In order to gain access to the roughly two hundred wartime diaries written by Japanese, Chinese, Russian, and American servicemen, I have relied heavily on the kindness of archivists, activists, and scholars around the world. One of the most underused resources for Japanese wartime materials are the many “Peace Museums” there. The documents are generally open to qualified researchers and the staff are always quite helpful. Although there is no comprehensive guide to these archives, many can be found through the Heiwa hakubutsukan / senso shiryokan gaido bukku (Aoki shoten, 2000), edited by the Rekishi kyoikusha kyogikai. Also, interested researchers should be all means make use of the “Peace Network” hosted by Ritsumeikan’s

While working closely with them, I found that archivists and curators there and at “Peace Osaka” keep the most comprehensive lists and up-to-date information on Japan’s many “Peace” and “War” Museums.

[1] See especially the discussion in Samuel Hideo Yamashita, Leaves from an Autumn of Emergencies: Selections from the Diaries of Ordinary Japanese (

[2] Ohama Tetsuya, Shomin no mita Nisshin / Nichiro senso: Teikoku he no ayumi (Tosui shobo, 2003), p. 50

[3] Tamon Jiro, Nichiro senso nikki (Tokyo: Saiho shobo, 1980, orig. 1912), introduction (original)

[4]

[5] See Linda Hoaglund, “Stubborn Legacies of War: Japanese Devils in Sarajevo.”

[6] Hoshi Toru, Watashitachi ga Chugoku de shita koto: Chugoku kikosha renkakukai no hitobito (

[7] In spite of vigorous opposition, Kanki Haruo was the first to successfully publish these accounts in the post-occupation era. Kanki Haruo, Sanko: Nihonjin no Chugoku ni okeru senso hanzai no kokuhaku (Kobunsha kappa, 1957).

[8] See Cook and Cook’s interview of Tanida Isamu in Japan at War: An Oral History (New York: The New Press, 1985), p. 29, where he denied the severity of the Nanjing Massacre.

[9] Kimura Genzaemon, Nicchu senso shussei nikki (Akita: Mumeisha shuppan, 1982), p. 16-17

[10]

[11] Nishimura Masaharu, Yokaren nikki (

[12] Kanoya: Kanoya koku kaijo jieeitai shiryokan: “Hara Kinosuke,” “Toyo nikki,” 1942.3.6-7

[13] “Kurozu Tadanobu,” “Jinchu nikki,” in Ono Kenji et alia, Nankin daigyakusatsu wo kiroku shita kogun heishitachi (Tokyo: Otsuki shoten, 1996), 1937.12.10. The pseudonym is Ono’s.

[14]

[15] Obara, op. cit., 1944.12.26, 1945.1.27, 2.13

[16] Kimura, op. cit., 1937.10.11

[17]

[18]

[19] “Ouchi Toshimichi,” “Jinchu nikki,” in Ono Kenji et alia, ed., 1937.12.7. The pseudonym is Ono’s.

[20] Umeda Fusao, Hokushi ten senki: Umeda Fusao jugun nikki, ed. Umeda Toshio (self-published, 1970), 1937.8.26; many thanks to Yoshimi Yoshiaki for pointing this text out to me.

[21]

[22]

[23] Liu Jiaqi, Zhenzhong riji (

[24] Stezhenskii, Soldatskii dnevnik: voennye stranitsy (

[25]

[26] Personal Collection: “Sakaguchi Jiro,” “Jinchu nikki,” 1939.1.4

[27] Kimura, 1938.12.1, 12.14