The Denationalized Have No Class: The Banishment of

Sonia Ryang

1.

In a recent article by Bumsoo Kim entitled “Bringing class back in: the changing basis of inequality and the Korean minority in

“[…] this study shows that the legal/institutional and socioeconomic structural changes in Japan for the past few decades, by decreasing ethnic inequality between Koreans and Japanese while increasing class inequality among Koreans, have made class more significant than ethnicity in understanding the inequality problematic of zainichi Koreans [i.e. Koreans in Japan].”[1]

Perhaps it is logical that an oppressed and marginalized ethnic minority, once it begins to receive the benefits of the affluence of the host society, albeit belatedly, would shed its markings of ethnicity and begin to take on the markings of class. Perhaps it is also logical to think that in such a situation class, rather than ethnicity, would become more relevant to forging identity. Unequivocally, however, I remain unconvinced by the argument that a particular category becomes “more significant” than certain others, since the marking of the oppressed is always necessarily multiply compounded.

Young Koreans in

wedding in traditional Korean style.

Nevertheless, what the above passage made me wonder—and what I found to be odd in it—was this: Koreans in Japan have always had incorporated class stratification: throughout the colonial period, during the US occupation and the entire post-war period, and to this day. The question is why, then, do some researchers think that class (and here, I take that they mean, through conflation, class consciousness and class differentiation) was not previously relevant to Koreans in

These questions led me to think not so much about class as about being human—notably, about when a human is not a human in

2.

It is no news to

But there is also the problem of cross-cultural and cross-national compatibility of categories. For example, the category of middle class captures a much broader population in the

But did class disappear equally and identically for Japanese and Koreans? In other words, is the mode of attrition of this concept from public consciousness the same for Japanese and Koreans in

I shall argue that there is an important mechanism at work here, involving legal, philosophical, and cultural elements, such that Koreans do not qualify to be included when one talks about class formation in Japan. Such exclusion of Koreans is not new. Throughout the postwar era, Korean residents in

The systematic exclusion of Koreans from

I do not attempt to fill this gap in the study of class among Koreans in

It will be necessary to start from the postwar process according to which emerging Korean expatriate movements effectively segregated Koreans from the Japanese mainstream, rendering them invisible in the context of

My final goal is to address the question of what it is to be human rather than “Korean” or “Japanese.” The reader will recognize that I do not propose to conceptualize Koreans as holding a transnational or supranational existence or, worse still, “cultural citizenship”— labels that in no way capture the fundamental reality of Koreans in Japan.[5] I shall show that the reason why Koreans in Japan continue to be viewed as irrelevant to, or not conforming with, class divisions within Japanese society is that they are merely and nakedly human and not members of a national polity. As I shall demonstrate below, this is an example of what Giorgio Agamben calls bare life, a form of existence that Hannah Arendt claims as the most perilous and precarious in the modern world.[6]

3.

It should not take too much to persuade the reader that, for a long time in postwar

And that violence, that ethnic Korean brand of violence, the intensity of which Japanese sectioned off in urban ghettos such as Sanya or Kamagasaki, readily found its way into Korean homes, fiercely inflicted upon weaker members of the family by the patriarch. The oft-quoted figure of the areru chichi or violent father, however, was also seen as burning with the flames of patriotism—there was always a good justification for his actions, as he had been destroyed, abused, exploited, and mentally injured by Japanese imperialism and colonial rule. Note that this portrayal was not found in the writings of Japanese commentators, let alone state-commissioned researchers, but in the writings of ethnic Korean writers in Japan.[8]

Strangely, however, the poverty of Koreans was not represented or perceived (by Koreans themselves) as a class phenomenon. It was, rather, an ethnic property. Just as

All of this, however, remained in the ghetto. Indeed, as long as Koreans did not try to take advantage of the limited forms of welfare offered by local municipalities, there was hardly anything the Japanese government owed them—that is, speaking from the perspective of

4.

Historically speaking, Koreans played an important role in the formation of the modern Japanese working class, Japanese trade unionism, and the Communist movement, both during the colonial and postcolonial periods. At the height of the Comintern’s intervention in the Korean and Japanese Communist movements during the 1920s, Korean communists in

When the war ended, there were 2.4 million Koreans in

The headquarter of Choryeon (top) and Mindan (bottom) in

The above belief in itself had not prevented leftist Koreans from forming their own organization. Within two months of the war’s ending, in October 1945, the League of Koreans in

5.

The left sought to build a supra-national class coalition. Ironically, such possibilities were augmented by the suppression of the left by Japanese and Occupation authorities. In 1949, Occupation authorities and Japanese military police responded to Choryeon’s support for

In the wake of these developments, Korean left-nationalists had no choice but to join the Japanese Communist Party, which had not been suppressed by the authorities. However, this marriage of convenience soon showed signs of strain. The frustrations of Korean members intensified following the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, compounded by disillusionment when the promised East Asian revolution failed to materialize. Fierce debate took place among Korean members, some stressing solidarity with the international working class movement, and others calling for prioritization of national goals and efforts to end the bloody conflict on the peninsula. This debate was brought to an end unexpectedly by communiqués issued by the North Korean Foreign Minister in 1952, which expressed

Following this development, Koreans withdrew en masse from the Japanese Communist Party and, after a few years of internal purges and fierce debates, re-organized as the General Association of Korean Residents in

Chongryun, in contrast to Choryeon, renounced all forms of intervention in

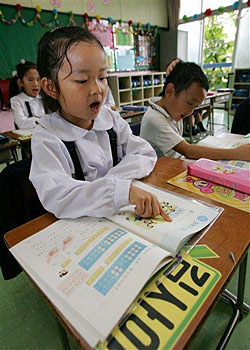

Ethnic Korean students study at a Chongryun-funded

elementary school in

In short, by 1955, within three years of being deprived of Japanese citizenship, Koreans in

From then on, Koreans were erased from

But that is not all. Up until 1965,

6.

The newly acquired name for the Korean left, “overseas nationals of the Democratic People’s

The repatriation of these individuals to

From 1959 to 1976, 92,749 individuals were “repatriated” from

As stated, it was not until 1965 that Koreans in

Morally speaking, this measure was, of course, unjustifiable: why should the Japanese government only provide benefits to those Koreans in

In this light, it should be clear how erroneous it is for many of those conducting research on Koreans in

7.

Arendt once wrote:

Not only did loss of national rights in all instances entail the loss of human rights; the restoration of human rights, as the recent example of the State of Israel proves, has been achieved so far only through the restoration or the establishment of national rights. The conception of human rights, based upon the assumed existence of a human being as such, broke down at the very moment when those who professed to believe in it were for the first time confronted with people who had indeed lost all other qualities and specific relationships—except that they were still human. The world found nothing sacred in the abstract nakedness of being human.[18]

But in

If birth and nation are one, then all the others who enter or wish to enter the national family must mimic, or are compelled to emulate, the nakedness of the newborn. The state—the guardian and prison guard, the spokesman and the censor-in-chief of the nation—would see to it that this condition was met.[19]

It is more than interesting to remember that persons who are naturalized in Japan are referred to as shinnihonjin or “new Japanese,” as if to indicate re-birth or a new life or, even more controversially, as kikajin, kika meaning a “return” to the correct state, implying that being Japanese or becoming Japanese is fundamentally right (and good) for humanity. This is all too deceptive, considering that a person who used to be only a naked human was not treated as human, while a person who had become a national was now treated as human for the first time.[20]

The enthusiasm and sense of profound commitment with which former Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi JunichirÅ (in power from 2001 to 2006) talked about the possible amendment of Article Nine of the Constitution need to be understood in this context, since this amendment would enable Japan to declare war against other nations: the possibility of war is the possibility of emergency, and further, a state of emergency is a state in which non-nationals can be exterminated more easily than at other times. Controversial behavior by the governor of

Ishihara ShintarÅ, the governor of Tokyo

For, the exception here derives from ex capere, meaning “outside,” and a state of exception is a state in which the law makes itself known by suspending itself. This is an effective way to control a population that exists outside ordinary national law.[22] Of course, undesirable elements can include both nationals and non-nationals. The unknowable number of victims in concentration camps in

ÅŒmura

This case points to an important factor in thinking about the bare life of stateless persons: in situations such as national emergencies or where certain decisions have been made at the national level, a person can easily become stateless, even if deemed to be in possession of a proper nationality. This was the case for Japanese Americans in the US after Pearl Harbor, when even those who were US citizens were sent to camps.[25] Not only that—inside the camps, they were studied as some kind of naked species whose reactions were meant to be used to inform the US government about the Japanese national character. Prominent anthropologists such as John Embree participated in this endeavor.[26] In other words, as stated above, states of emergency such as wars make anything possible—the elimination of humans, detention of undesirable elements, and deprivation of some citizens of their civil rights as the sovereign state sees fit.

The fact that the ÅŒmura camp has been relieved of its special duty as a place of detention for Koreans does not mean that the possibility of being incarcerated in a similar institution in future has been permanently removed. In the case of a national emergency, such as a war of the kind that Japan’s recent prime ministers were eager to have the option of participating in, it is non-nationals that would be the first to face detention in the name of national security.[27]

8.

In 1981, simultaneous with

It was during the 1980s that many situational (not structural) changes were made in the topography of Koreans in Japanese society. First, there was an influx of Koreans from

In 1992, all Korean permanent residents, including those who had acquired permanent residence following the 1965 treaty and those who had acquired it in the years following 1981, found themselves under a common classification as special permanent residents, or tokubetsu eijūsha. This change was accompanied by a diverse range of improvements in the residential status of Koreans in

In the meantime, ambiguity remains the constant for Koreans in

On the other hand, those Koreans in

It would be this group of stateless Koreans, whose form of existence is nakedly human without the official recognition of any nation-state, that would be the first to be loaded onto the trucks, possibly after being given one hour’s notice to pack one item of luggage, and sent away to the camps. The erasure of Koreans from

9.

Turning our attention to internal class-consciousness, or the lack thereof, among Koreans in

In Chongryun’s official rhetoric, all Koreans in

Chongryun was able to sustain this notion for two decades or so due to the ethnic marginalization of Koreans as a whole in

Class divisions evidently existed among Chongryun followers from the very beginning. But this reality was made part of the larger expatriate cause for the reunification of

It was from the early 1980s that inequalities and the uneven distribution of power inside Chongryun, and within

We must remember that, whereas the transition from a labor-intensive to a capital-intensive economy occurred during the 1960s for the Japanese mainstream, it only reached Koreans in

Post-poverty younger generations were altogether different. First off, they were employable in Japanese sectors, unlike their uneducated parents. In a cultural sense, too, they were no longer brought up simply with nationalism, but were also well versed in Japanese contemporary popular culture and socially accepted standards. Politically, in comparison with their parents and grandparents, they no longer had such a fierce interest, nor such a deep personal and professional investment, in homeland-oriented politics.

As stated above, by becoming permanent residents of

Chongryun visitors to

On a more personal level, Chongryun visitors were harassed, ridiculed, and simply treated with very little respect: flaws in their Japanese-accented Korean were met with contempt, and even their clothing, hairstyles and posture were monitored and pedantically corrected. For many, following a wave of emotional upheaval during their initial visit, repeat visits only confirmed their disillusionment. Chongryun Koreans, even including cadres, who had been born and grew up in

Such looming skepticism coincided with changes in the economic status of Koreans in

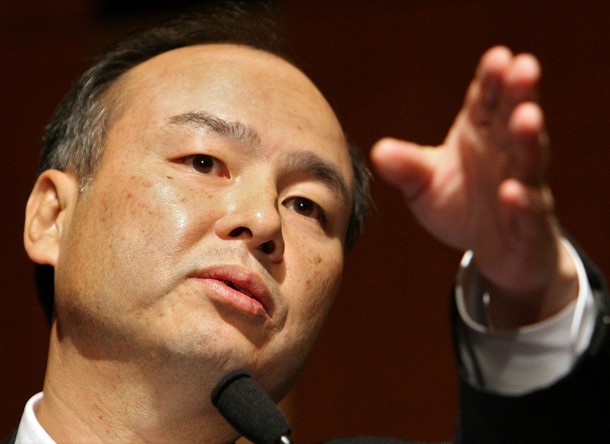

Son Masayoshi, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Softbank Mobile

as well as Softbank group. Son is one of Japan’s richest entrepreneurs.

The trajectories of such individuals can be contrasted with those of Koreans newly arriving in

More importantly, at least during the initial stage following their migration to

10.

I have dwelt so far on the topology of Koreans in

Where the Korean data deviates from the Japanese pattern is in the patterns for advancement in society. Whereas for Japanese respondents, length of education correlated with social status, education did not secure comparable upward mobility for the Koreans. At the same time, as many as 70 percent of Korean respondents primarily depended on family and friends, that is, ethnic connections in order to secure employment, and they predominantly ended up among the ranks of the urban self-employed.[34] In Kim’s sample, 42.3 percent of Japanese respondents are white-collar workers as opposed to 26.6 percent of their Korean counterparts, while 23.2 percent of Japanese respondents are self-employed as opposed to 52.1 percent of their Korean counterparts.[35] Of particular significance is the fact that the educational level of Korean fathers was not reflected in the degree of social advancement of their sons, demonstrating that cultural capital does not have the same value for Koreans and Japanese once they are placed in the Japanese (national) job market.[36] A key difference lies in the fact that Koreans are unable to turn to formal Japanese government agencies in order to secure employment given their non-national status (I have already discussed what it means not to have national status).

The breakdown of occupations for Koreans is also indicative: 11.57 percent working in restaurants, 16.07 percent in construction, 12 percent in simple manufacturing, and 8.3 percent unemployed; hardly any are found in the professional or executive sub-class. Not surprisingly, Kim finds that the older the Korean male, the more disadvantaged he is in the job market.[37]

Myungsoo Kim concludes “that employment opportunities and status attainment processes among Korean minority members [in Japan] are in fact far from being fully equal in comparison with the Japanese as the data analyzed in this article indicates, even though the outcome of Korean minority status attainment here appears to have reached levels similar to those of the Japanese.”[38] Compare this with Bumsoo Kim, whose words are quoted in the opening of this article, arguing that class is becoming a more important factor than ethnicity when thinking about Koreans in

We are dealing here with a parallel phenomenon: the job attainment, living standard, income level and other quantitative indicators documented for Koreans in Japan stand on fundamentally different mathematical (figuratively speaking, that is) footing than that of Japanese nationals. Consider the fact that the government retirement plan is unavailable to many first-generation Koreans in

It is true that many local governments have opened the door to Koreans and non-Japanese, allowing them to obtain low-ranking civil service jobs—perhaps a first step in altering the excluded status of Koreans in Japan.[39] But, a high hurdle remains in the quest for civil status, as Japan is not a federation or a union of states: as long as the central government strenuously excludes Koreans in Japan, there is little that local municipalities can do. It came as no surprise, for example, that the Japanese Supreme Court upheld the decision by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government to bar a civil servant from taking an exam for promotion to a managerial position due to her South Korean nationality; that is, her not being Japanese.[40] In other words, Koreans can be civil servants so long as they stick to sweeping the floors and cleaning the bathrooms; if they wish to be supervisors or managers, they will need to be reminded of the fact that they are merely human and not citizens.

As long as the system of nation-states governs our world, refugees, immigrants, and other stateless persons have no place in the domestic class stratification within individual nation-states. This does not mean that it is not possible (for scholars) to classify them or measure them according to national socio-economic classifications and surveys. Neither does this mean that they do not have class consciousness. But in the case of Koreans in

In the US, poverty is racialized with the result that unemployment, high crime rates, lack of education, drug abuse, and other paraphernalia that fill the closet of poverty are associated with non-whiteness and other ethnic markers. Nevertheless, poverty which disproportionately confronts people of color and other minorities, is a national problem, one requiring the attention of Congress, national and local government budgets, and the object of legal and institutional reforms. Such is not the case for Koreans in

Acknowledgements:

This paper was originally prepared for a workshop in

Endnotes:

[1] Kim (2008: 871).

[2] Perhaps the best-known Althusserian class theorists would be Poulantzas (1973), Therborn (1986), and of course, Althusser (1984, 1990) himself. For Bourdieu, see (1977, 1984).

[3] Thompson (1964) and, more classically, Engels (1993).

[4] Of course, the increasing numbers of homeless in

[5] I regard the view that facilely sees Koreans in

[6] See Agamben (1995) and Arendt (2000). See below in the text.

[7] See Weiner (1989).

[8] An array of historical and recent literary representations can testify to this effect, starting from writers such as Kin Kakuei (1970) and Ri Kaisei (1972), and later including Yang Seog-il (1998), and Kaneshiro (2000).

[9] History testifies, however, that the Korean members had to work extra hard, risking their lives and proving their bravery, in order to earn the trust of their Japanese comrades within the party, while it was almost unheard of for a Korean to rise to high-ranking office within the trade unions or the party in

[10] Wagner (1951: 95).

[11] Kim (1946).

[12] Martial Law was proclaimed in

[13] The North Korean initiative failed. The Japan-ROK treaty was not signed until 1965. Until then,

[14] Hiroyama (1955: 10).

[15] Ryang (1997: 122).

[16] Morris-Suzuki (2007). Morris-Suzuki discovered, by investigating newly de-classified papers, that the role played by the Japanese Red Cross was much more significant and decisive than had been previously thought.

[17] Arendt (2000: 38).

[18] Arendt (2000: 41).

[19] Bauman (2003: 130).

[20] An average of about 10,000 Koreans are naturalized each year as Japanese citizens. See Ministry of Justice statistics.

[21] Ishihara made the reference to Koreans and other non-nationals in

[22] Agamben (2005). Much of Agamben’s ideas are derived from Schmitt’s notion of sovereignty (Schmitt 1922).

[23] See, for example, Kang (2001). For a totalitarian society, see Arendt (2000: 119-145).

[24] Pak (1969), Yoshitome (1979), and Pak (1983). Due to the South Korean government’s reluctance to accept any deportees from

[25] See for example, Kurashige (2002).

[26] Ryang (2004: Ch.1) for a discussion.

[27] Today ÅŒmura

[28] Kim (2005).

[29] It needs to be added that there has been a huge increase in the number of Koreans in

[30] My two visits in 1985 as a reporter for the Chongryun media organ, Choseon Sinbo (Korea Daily), attest to this. I was routinely tricked in relation to where I should meet my supervisor, where to go, and whom to talk to, while my hotel rooms were randomly changed every one or two days. I think this was done simply to confuse, exhaust, and harass me, so that I would not be able to properly complete my assignment covering the family reunions.

[31] Ryang (1997) discusses this issue.

[32] Ethnographic studies and other forms of research on Korean newcomers in

[33] Kim (2003: 8).

[34] Kim (2003: 14).

[35] Kim (2003: 9).

[36] Kim (2003: 14-15, 12).

[37] Kim (2003: 12, 11).

[38] I discuss this matter pertaining to ethnic ethics of care and justice in Chapter 4 “Diaspora and the Ethic of Care: A Note on Disability, Aging, and Vulnerability of the De-nationalized” of my Writing Selves in Diaspora: Ethnography of Autobiographics of Korean Women in Japan and the US (2008).

[39] Ahn (2000).

[40] Rusling (2005).

References:

Agamben, Giorgio (1995) Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Stanford:

Agamben, Giorgio (2005) State of

Ahn, Doek Keun Matthew (2000) “Reflections on Voting, Identity, and Self-Affirmation in Japan,” Harvard Asia Quarterly Autumn 2000

Althusser, Louis (1986) “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes Towards an Investigation),” Essays on Ideology,

Althusser, Louis (1990) For Marx,

Arendt, Hannah (2000) “The Perplexities of the Rights of Man,” The Portable Hannah Arendt,

Bauman, Zygmunt (2003) Liquid Love: On the Frailty of Human Bonds,

Bourdieu,

Bourdieu,

Engels, Friedrich (1993) The Condition of the Working Class in

Hiroyama, Shibaaki (1955) “Minsen no kaisan to chÅsen sÅren no keisei ni tsuite” (On the dissolution of Minjeon and the emergence of Chongryun), KÅanjÅhÅ 22: 5-11.

Inokuchi, Hiromitsu (2000) “Korean Ethnic Schools in Occupied

Iwamura, Toshio (1972) Zainichi chÅsenjin to nihon rÅdÅsha kaikyÅ« (Koreans in

Kaneshiro, Kazuki (2000) Go,

Kang, Chol-hwan (2001) The Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in a North Korean Gulag,

Kim, Bumsoo (2008) “Bringing Class Back in: The Changing Basis of inequality and the Korean Minority in

Kim, Myungsoo (2003) “Ethnic Stratification and Inter-Generational Differences in

Kim, Tae-gyu (2005) “New individual identification system sought,” The Korea Times Feb. 24, 2005.

Kim, Tu-yong (1946) “Nihon ni okeru chÅsenjin mondai” (The Korean question in

Kin, Kakuei (1970) Kogoeru kuchi [Frozen mouth],

Ko, Seonhui (1995) “’Shinkankokujin’ no teijÅ«ka—enerugisshuna gunzÅ” [The settlement of “new Koreans”—their energetic image], in H. Komai (ed.) TeijÅ«ka suru gaikokujin [Settling foreigners],

Koshiro, Yukiko (1999) Transpacific Racisms and the

Kurashige, Lon (2002) Japanese American Celebration and Conflict: A History of Ethnic Identity and Festival, 1934-1990,

Lee, Seijaku (1997) Zainnichi kankokujin sanseino muneno uchi [Inner thoughts of a third-generation Korean in

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa (2007) Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Pak, Cheong-gong (1969) ÅŒmura shÅ«yÅjo (The ÅŒmura camp),

Pak, Sun-jo (1983) Kankoku, Nihon, ÅŒmura shÅ«yÅjo (

Poulantzas, Nicos (1973) Political Power and Social Class,

Ri, Kaisei (1972) Kinuta o utsu onna (The woman who fulled clothes),

Rusling, Matthew (2005) “High Court Bolsters Japan’s Anti-Immigrant Image,” Asia Times Online Feb. 8, 2005 http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Japan/GB08Dh01.html

Ryang, Sonia (1997) North Koreans in

Ryang, Sonia (2000a) “The North Korean Homeland of Koreans in

Ryang, Sonia (2000b) “

Ryang, Sonia (2002a) “A Dead-end in a Korean Ghetto: Multiple Readings of a Complex Identity in Gen Getsu’s Akutagawa-winning Novel Where the Shadows Reside,” Japanese Studies 22 (1): 5-18.

Ryang, Sonia (2002b) “A Long Loop: Transmigration of Korean Women in

Ryang, Sonia (2004)

Ryang, Sonia (2008) Writing Selves in Diaspora: Ethnography of Autobiographics of Korean Women in

Schmitt, Carl (1922) Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty,

Tai, Eika (2004) “‘Korean Japanese’: A New Identity Option for Resident Koreans in

Tatsumi, Nobuo (1966) “Nikkan hÅteki chii kyÅtei to shutsunyÅ«koku kanri tokubetsuhÅ” (The Japan-ROK legal status agreement and the special provision for the immigration control act), HÅritsujihÅ 38 (4): 59-67.

Tei, Daikin (2001) Zainichi kankokujin no shūen (The end of Koreans in

Therborn, Goran (1986) What Does the Ruling Class Do When It Rules?: State Apparatuses and State Power under Feudalism, Capitalism and Socialism,

Thompson, Edward P. (1964) The Making of the English Working Class,

Wagner, Edward (1951) The Korean Minority in

Weiner, Michael (1989) Origins of the Korean Community in

Yang, Seog-il (1998) Chi to hone (Blood and bone),

Yoshitome, Roju (1977) ÅŒmura chÅsenjin shÅ«yÅjo (The ÅŒmura Korean camp),

Sonia Ryang teaches anthropology at the

She wrote this article for Japan Focus. Published June 8, 2008.