Waterboarding: The Meaning for Japan

Kinue Tokudome

“If you look at the history of the use of that technique used by the Khmer Rouge, used in the inquisition, used by the Japanese and prosecuted by us as war crimes, we prosecuted our own soldiers in Vietnam, I agree with you, Mr. Chairman, waterboarding is torture.” [1]

The above statement made by Eric Holder during his confirmation hearing for Attorney General marked a clean break from the policy of the Bush administration on “waterboarding,” [2] the interrogation technique used by the CIA on at least three Al-Qaida suspects, and on the general issue of the use of torture in US interrogation.

If the Japanese people were surprised to see their country grouped together with the Khmer Rouge, medieval torturers who brutally persecuted heretics, and US soldiers during the Vietnam War, some of whom were court-martialed, [3] they should not have been.

Waterboarding in Vietnam

In the past few years, waterboarding by the Japanese military has often been mentioned in the discussion on this topic in Congress, the media, and among those who had unforgettable memories of experiencing it and witnessing it.

Senator Ted Kennedy, in opposing the confirmation of Michael Mukasey as Attorney General, made the following statement on the Senate floor on November 8, 2007.

It is illegal under the Geneva Conventions, which prohibit “outrages upon personal dignity,” including cruel, humiliating, and degrading treatment. It is illegal under the Torture Act, which prohibits acts “specifically intended to inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering.” It is illegal under the Detainee Treatment Act, which prohibits “cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment,” and it violates the Constitution. The Nation’s top military lawyers and legal experts across the political spectrum have condemned waterboarding as illegal. After World War II, the United States prosecuted Japanese officers for using waterboarding. What more does this nominee need to enforce existing laws? [4]

Senator and presidential candidate John McCain mentioned waterboarding by the Japanese during his appearance in CBS’ “60 Minutes” on March 9, 2008. He answered when he was asked if “waterboarding” was torture:

Sure. Yes. Without a doubt…We prosecuted Japanese war criminals after World War II. And one of the charges brought against them, for which they were convicted, was that they water-boarded Americans. [5]

Some powerful reports on waterboarding by the Japanese military appeared in major newspapers. Evan Wallach, a judge at the U.S. Court of International Trade in New York, wrote an opinion piece, “Waterboarding Used to Be a Crime,” that was published in the Washington Post on November 4, 2007:

After Japan surrendered, the United States organized and participated in the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, generally called the Tokyo War Crimes Trials. Leading members of Japan’s military and government elite were charged, among their many other crimes, with torturing Allied military personnel and civilians. The principal proof upon which their torture convictions were based was conduct that we would now call waterboarding.

Judge Wallach quoted the testimony of a victim:

They laid me out on a stretcher and strapped me on. The stretcher was then stood on end with my head almost touching the floor and my feet in the air. . . . They then began pouring water over my face and at times it was almost impossible for me to breathe without sucking in water. [6]

Former British POW of the Japanese, Eric Lomax, who was waterboarded by the Japanese military police, the Kempeitai, during World War II, wrote about his ordeal for the Times of London on March 4, 2008. A lieutenant in the Royal Signals, Lomax was caught with his fellow POWs and interrogated about their secretly assembled radio.

The whole operation was a long and agonising sequence of near-drowning, choking, vomiting and muscular struggling with the water flowing with ever-changing force. . . . How long the torture lasted, I do not know. It covered a period of some days, with periods of unconsciousness and semi-consciousness. Eventually I was dumped in my cell, which was so small it offered little scope for movement. At about this time two of my colleagues were beaten to death. Their bodies were dumped in a latrine where they may well remain to this day. [7]

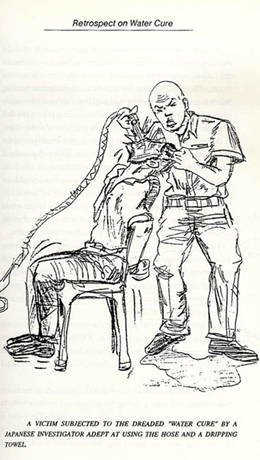

Gustavo Ingles was tortured mercilessly by the Japanese military when he was captured as a guerrilla in the Philippines. In 1992, he published a book entitled, “Memoirs of Pain”, where he described various types of waterboarding, including ones he was subjected to. [8] Illustrations of waterboarding he received and witnessed were included in his book.

Drawing of waterboarding (Illustration by Rey Rillo)

The experience of witnessing waterboarding also remains etched in the memories of those who saw it firsthand. Lester Tenney, a Bataan Death March survivor, wrote in his memoir, My Hitch in Hell, about witnessing his fellow American soldier waterboarded while he himself was being tortured. It happened after Tenney was recaptured by the Japanese soldiers following his escape from Camp O’Donnell and a brief stay with guerrillas. The Japanese wanted to extract information about the guerrillas from Tenney.

Lester Tenney one month after liberation, Sept.1945

For what seemed like an eternity, I just stood and waited for them to say something. At last the commander gave the interpreter instruction. A few minutes later, a guard came into the room, raised his rifle, flipped it around so that the stock of the gun was facing me, and with one swift movement hit me with the butt squarely in the face. With one fell swoop, I started to bleed from each and every part of my face. I knew that my nose was broken, that a few teeth were missing, and that it hurt like hell. Blood was gushing down my shirt to my pants. Everything was getting wet from the flowing blood. All the while the Japanese were having themselves a good laugh. I guess I was truly the butt of the joke.

While I was trying to straighten up, one of the guards hit me across the back with a piece of bamboo filled with dirt or gravel, and once again I fell to my knees. I got up as fast as I was able and stood at attention in front of the guards. I was left standing there for about an hour, then three guards came in and dragged me out to the parade ground, which had been the playground of the school.

Once outside, I saw they had another American spread-eagled on a large board. His head was about ten inches lower than his feet, and his arms and feet were outstretched and tied to the board. A Japanese soldier was holding the American’s nose closed while another soldier poured what I later found out was salt water from a tea kettle into the prisoner’s mouth. In a minute or two, the American started coughing and throwing up water. The Japanese were simulating a drowning situation while the victim was on land. Every few seconds an officer would lean over and ask the prisoner a question. If he did not receive an immediate answer he would order that more water be forced into the prisoner’s mouth.

I could not believe my eyes. Torture of this nature was something I had read about in history books. It was used during the medieval times, certainly not in the twentieth century. My God, I wondered, what is in store for me? [9]

Walter Riley was 12 years old when he witnessed waterboarding. He saw it through a hole in the fence surrounding Santo Thomas University in Manila that was converted into a civilian internees’ camp by the Japanese military during World War II. More than 4,000 civilians from the United States and other Western countries, including many children, endured more than three years of internment under harsh conditions. Walter recently wrote to this author:

Walter Riley in 1946

One day late in 1944, some of us kids were crawling through the weeds in the field between the gym and the front gate. The weeds were so tall we were able to crawl right up to the fence without being seen. I looked through a hole in the fence and saw a young Filipino man tied in a chair with a water hose in his mouth. I got to see the “water cure” up close. Somehow, I was able to keep from making any noise and quickly crawled away from the fence. I can still see the water coming out of the Filipino’s mouth when the soldier hit him in the stomach.

Some things are hard to forget.

On his second day in office, President Obama kept his campaign promise to undo many of the previous administration’s contentious policies on war on terror. He ordered that the prison at Guantanamo Bay be closed within a year and that detainees be treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventiosn. The United States, he pledged, would prosecute the ongoing struggle against violence and terrorism “in a manner that is consistent with our values and our ideals.”

While heated discussion of waterboarding was taking place in the US and around the world, Japan remained largely silent. The mainstream media reported on the debate in the United States, but did not report that their country’s history of waterboarding was often mentioned outside of Japan in this discussion. But didn’t the world expect Japan to contribute to the discussion by providing insight based on reflection on the nation’s past behavior?

It is not easy for any nation to revisit its dark history. But the Japanese people should note that waterboarding by the Japanese was not the only example mentioned in this discussion. Americans recalled and criticized examples of waterboarding by US troops in the Philippines-American War of 1898-1902 and by US soldiers during the Vietnam War. The point of such discussions is not to condemn past behavior for its own sake, but to learn from the past so as to find appropriate ways for nations to protect their people from contemporary threats while hewing to their highest principles. [10]

Japanese Prime Minister Taro Aso, under vigorous questioning in the Diet, recently admitted that 300 Allied POWs (101 British prisoners, 197 Australians and two Dutch) had worked at his family coalmine during World War II. [11] Japanese Foreign Minister Nakasone Hirofumi also made this statement in the Diet about the Geneva Convention which prohibits torture:

I believe it is very meaningful to join such major agreements of international humanitarian law from the standpoint of both promoting the development of international humanitarian law as well as gaining greater trust in Japan in the international community.[12]

There were nearly 130 POW camps throughout Japan during World War II with some 30,000 Allied POWs who did forced labor under appalling conditions in mines, docks, and factories owned by companies such as Mitsui and Mitsubishi. More than 3,000 POWs died on Japanese soil. The Prime Minister has not yet acknowledged that the POWs at Aso Mining were forced to work, much less that they were abused. But testimonies of former POWs who worked at Aso Mining paint a grim picture of the conditions under which they were placed. [13]

The waterboarding that Senator Kennedy mentioned during the debate on the Senate floor took place at Fukuoka POW camp # 3, not too far from Fukuoka POW camp #26 where POWs worked for Aso Mining. POWs held in Japan were forced laborers and they were subjected to abuse and even torture such as waterboarding. There were also tens of thousands of forced laborers from the Korean Peninsula and China who were often subjected to even harsher treatment than Allied POWs.

Only after the Japanese government acknowledges these historical facts, and both government and corporations take steps to apologize and solve the issues of compensation, will the statement by Foreign Minister Nakasone on the Geneva Convention become convincing.

It is also essential for the Japanese business community to make a clean break from its World War II history of using forced laborers. [14] Their German counterpart has already set an example. The international community expects no less from Japan. [15]

Although their memories of waterboarding are painful, some individuals are making efforts to make sense out of their experience and to come to terms with it. Former POW Eric Lomax forgave Nagase Takashi, who was the interpreter while he was waterboarded. He also met with Komai Osamu, the son of the Japanese officer who ordered the torture of Lomax and who was executed after the war as a war criminal. When Komai traveled to England and apologized for his father’s action, Lomax thanked him for traveling far to meet him and said, “It is extremely rare for a victim of war like myself to be able to receive this kind of guest. I am very happy that you came.”

Komai Osamu visiting Eric Lomax who was tortured by his father’s order

Lester Tenney visited Japan in spring 2008 and shared his POW experience with many young people there. He also asked the Japanese government and companies to acknowledge their abuse of POWs during World War II, apologize for it, and offer a reconciliation project such as inviting former POWs and their families to Japan.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the last revision of the Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. It is also the United Nation’s Year of International Reconciliation. It is hoped that it will be a year for Japan to find a moral voice. Japan can do so by facing the past squarely, achieving reconciliation with former victims, and winning the trust of the International community.

Kinue Tokudome is Executive Director of the US-Japan Dialogue on POWs.

This is a revised version of an article that she wrote for Gunshuku Mondai Shiryo (Materials on Problems of Disarmament).

She has the following articles and others published at The Asia-Pacific Journal:

The Bataan Death March and the 66-Year Struggle for Justice

“Comfort Women”, the US Congress and Historical Memory in Japan

Recommended Citation: Kinue Tokudome, “Waterboarding: The Meaning for Japan” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 4-3-09, January 24, 2009.

The following recent related texts explore issues of war crimes, atrocities, historical memory, apology and compensation, offering Japanese and American archival documentation and comparative perspectives on the legal and humanitarian issues at stake.

Michael Bazyler, Japan Should Follow the International Trend and Face Its History of World War II Forced Labor.

Lawrence Repeta, Aso Revelations on Wartime POW Labor Highlight the Need for a Real National Archive in Japan.

Consult in addition the category “War Crimes and Atrocities” for numerous related articles, particularly those by William Underwood, Oe Kenzaburo, Herbert Bix, Jennifer Lind, Philip Seaton, Mark Selden, Yuki Tanaka, Teresa Svoboda and Paul Kramer.

Notes

[1] Holder video here.

[2] Details of the development of the Bush administration’s policy on waterboarding are here.

[3] See “Waterboarding Historically Controversial” The Washington Post, Oct, 5, 2006. Page A17.

[4] Congressional Record, Senate, November 8, 2007, p .S. 14166.

[5] “McCain Looks Ahead,” CBS 60 Minutes, March 9, 2008. McCain’s live comments on waterboarding are here.

[6] Washington Post, “Waterboarding Used to Be a Crime“

[7] Here

[8] Gustavo Ingles, Memoirs of Pain (Metro Manila: Mauban Heritage Foundation, 1992), p.27.

[9] Lester I. Tenney, My Hitch in Hell (Washington: Brassey’s, 1995), pp. 87-88.

[10] See for example, “Water Cure: Debating torture and counterinsurgency- a century ago” by Paul Kramer, New Yorker, February 25, 2008. Kramer chronicled the debate on American soldiers’ torturing Filipinos with water during the Philippines-American War. He concluded that although some Americans at that time were outraged by the “cruelty” and “barbarities” exhibited by US soldiers, in the end the nation as a whole chose not to deal with it squarely. Kramer’s thoughts on the relevance of this century old debate on “water cure” to today’s situation can be found at Japan Focus.

[11] For Prime Minister Aso’s admission see Japanese PM Taro Aso’s family business used British PoWs. Prime Minister Aso also admitted that there were Korean workers at Aso Mining during the Upper House plenary session on Jan. 7, 2009.

[12] Foreign Minister Nakasone Hirofumi before the Upper House Committee on Foreign Affairs and Defense, Dec. 18, 2008.

[13] Former Australian POW Arthur Gigger who was forced to work at Aso Mining said that food and clothes were inadequate. (See “Proof of POW Forced Labor for Japan’s Foreign Minister: The Aso Mines” by William Underwood.) Another former POW Joe Coombs recently told the Radio Australia about the condition of the Aso Mining, “The coal mines were the worst of the lot, I’m sure the mines that we were working in were old mines that had been re-opened. And the coal that we were taking out should have been left there to hold the mine together and we had several major falls while we were working there.”

[14] See “The Japanese Court, Mitsubishi and Corporate Resistance to Chinese Forced Labor Redress” by William Underwood for the account of Japanese corporations’ resistance to dealing with the forced labor issue.

[15] See Michael Bazyler’s forthcoming article at Japan Focus for discussion of many issues relevant to the present article.