Pearl Harbor and September 11: War Memory and American Patriotism in the 9-11 Era

By Geoffrey M. White

Recent events provide a stark reminder that we live in a global society where major events affect everyone, across borders, regions, and cultures. Yet, despite the intensification of global interconnections effected by worldwide flows of capital and culture, the meanings of September 11 continue to be constructed in sharply nationalist terms. This may be especially so for Americans who were the primary targets of the 2001 attacks, and who generally see them as attacks on the nation (as, indeed, they seem to have been intended). As John Dower has observed, one need only look at the outpouring of patriotic responses to September 11 in the United States, marked by flags, songs, ceremonies, and commentaries (as well as military actions) enunciating national pride and solidarity. (John Dower, in remarks made at a symposium marking the 60th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, observed that these responses reminded him of accounts of Japanese nationalism in the early stages of the Asia-Pacific War.) But the �new� American patriotism being produced in the post-9-11 era frequently invokes earlier forms of patriotism, especially in images of World War II, the �good war.� Here I reflect on the role of memories of the bombing of Pearl Harbor in (re)producing American patriotism in the 9-11 era, focusing particularly on cultural practices of remembrance.

It will be obvious to anyone who has viewed American media coverage of 9-11 and the subsequent �war on terror� that these events have given rise to a resurgent patriotism in the U.S. not seen since World War II (In this paper I use the American name for the war, �World War II.�). Even in Hawai�i, far from the mainland United States, houses along the streets of most neighborhoods routinely display American flags; stores sell flags, pins, and banners; and cars everywhere sport bumper stickers proclaiming national pride and unity. Whether swept up in this renewed patriotism, or worried by the concomitant rise of racism and unchecked militarism, nearly everyone has been affected.

How it is that such distinctly national meanings are produced in the face of intensifying globalization? In addressing this question I focus on memorial practices as one means of and for (re)imagining national communities. I am particularly interested in the manner in which memorial practices articulate personal narratives (of sacrifice or suffering) with larger histories of the state. Of all the kinds of histories that nations construct of themselves, histories and memories of war are among the most effective ways of imagining national community and reproducing visions of a shared past. Histories (and memories) do not just happen. They are told, written, filmed, and otherwise represented for specific times, places, and audiences. In other words, histories and memories are mediated�mediated by cultural ways of telling stories and by the people who tell them. Attention to the constructed nature of history has led to an increasing amount of writing on historical memory�on the ways that people and societies remember significant events. To the extent that the term �memory� refers to the meaning of events rather than the events themselves, then this paper is primarily concerned with memory�with the (re)production of September 11 as part of the American past, however contested. I make this point in order to be clear that my purpose in exploring the ways people draw parallels between Pearl Harbor and September 11 is not to confirm or disconfirm the historical basis for these comparisons, but to ask what they tell us about the ongoing nationalization of history and memory of the September 11 attacks. (In this paper I focus primarily on representations of the World Trade Center attacks; although a fuller analysis would include the attack on the Pentagon and the crash of United flight 93.)

How, then, are September 11 and its aftermath represented as a distinctly American story? In pondering this question I want to focus on the role of narratives of World War II, and of Pearl Harbor in particular, in framing the meanings of September 11 and the subsequent �war on terror.� Since we have now had sixty years of remembering the Pacific War, we may also ask what we have learned about war remembrance that may help us better understand the meanings of 9-11 now emerging in American public culture. As September 11 is memorialized and institutionalized in public discourse of all kinds, its significance is becoming solidified for generations to come.

For Americans, the events of September 11 are a human catastrophe of a sort not seen since World War II. It is not surprising, then, that in the United States images and stories of World War II have been invoked repeatedly to give meaning to September 11, to understand events that otherwise seem to defy comprehension. Given that histories of war are almost always intensely national in character, appropriations of WWII imagery for the purpose of representing September 11 have the effect of further nationalizing understandings of this most recent epoch of violence. I explore these influences first by examining invocations of the Pacific War in representations of September 11, focusing on Pearl Harbor, the World War II event most frequently linked to 9-11. I then ask how practices of war remembrance, especially memorial practices honoring the dead, work to give September 11 its distinctly national character in American consciousness. And just as World War II memory is shaping understandings of September 11, so September 11 has had a profound effect on the ways Americans view World War II�a history that has continued to evolve and transform during the last 60 years. This paper reflects on the ongoing transformation of American memories of Pearl Harbor in the post 9-11 era.

It may seem obvious to say that much of the emotional power of representations of Pearl Harbor and September 11 derives from the fact that, at base, both are concerned with memorializing the dead. Both Pearl Harbor and September 11 are about the sudden, violent death of thousands of people. As such they are not only recalled as history, as abstract, if important events, but they are marked with ceremonies to remember people who died a violent death–by those who survived, by loved ones, and by fellow citizens drawn into the story through imaginations and identification. In this paper I discuss practices of memorialization emerging with September 11,

Invoking Pearl Harbor after September 11

Historians have long noted a certain asymmetry in American and Japanese remembrances of the Pacific War. Whereas Americans have devoted extensive resources to remembering Pearl Harbor, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain problematic, marginal memories (Lifton 1995). In Japan, where war memories in general are more ambivalent and contested than in the U.S., the atomic bombings are, for obvious reasons, a larger focus of national interest. Whereas the official center of American memory of Pearl Harbor is centered on the national monument and shrine constructed over the sunken battleship USS Arizona, efforts to mount even a temporary exhibit of the atomic bombings at the Smithsonian Institution 1995 resulted in deep controversy and cancellation of the exhibit (Linenthal and Engelhardt 1996).

Given this background, it should not be surprising that Pearl Harbor quickly became a reference point for American interpretations of September 11, and that Hiroshima and Nagasaki have been notable absences (despite the appropriation of the phrase �ground zero� to refer to the site of destruction at the World Trade Center). Even though the reasons for comparing September 11 to Pearl Harbor may seem obvious to Americans, the absence of reference to the atomic bombings is also notable given that the scene of urban devastation around the World Trade Center site is referred to as �ground zero,� a term associated with the original testing of atomic bombs at Los Alamos during World War II. Furthermore, both events involved massive civilian casualties from attacks unimaginable prior to the event.

These comparisons have been contested on the obvious grounds that Pearl Harbor was a military strike on a military target. For example, Gary N. Suzukawa voiced these sentiments in a letter to the Honolulu Advertiser immediately after the 9-11 attacks (September 18, p. A-13):

�No comparison to Pearl Harbor� As an American of Japanese ancestry, I take strong exception to those in the news media comparing the cowardly attack on the World Trade Center to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Last Tuesday is far and away much, much worse for all Americans. The attack on Pearl Harbor was a military strike against a military target. Despicable, sneaky, call it what you will, but the attack on Pearl Harbor is not in the same ballpark. . . .

Noam Chomsky has challenged the comparison by noting the erasure of American imperialism implied by references to Hawai�i as the United States. In a published interview about September 11, Chomsky commented, �For the United States, this is the first time since the War of 1812 that the national territory has been under attack, or even threatened. Many commentators brought up a Pearl Harbor analogy, but that is misleading. On December 7, 1941, military bases in two U.S. colonies were attacked�not the national territory, which was never threatened. The U.S. preferred to call Hawaii a �territory,� but it was in effect a colony.�(2002: 11-12).

Yet many others have drawn comparisons that play upon cultural and psychological meanings as well as visual and narrative similarities of the two events (as opposed to any kind of comprehensive historical accounts). For a country that had been in the privileged position of never witnessing the destructive effects of modern warfare on its own soil, both Pearl Harbor and 9-11 stand out as attacks at �home� that caused sudden, massive casualties and led to protracted war. These similarities, it seems, were enough to compel comparisons from the first moments following the September 11 attacks. References to Pearl Harbor were immediate and widespread in news reporting on the attacks. On the one hand, the sheer scale of death and destruction was enough to evoke comparisons, regardless of the nature of the attacks. Television news anchor Tom Brokaw, reporting that day on NBC, said �This was the most serious attack on the United States since Pearl Harbor� (www.abcnews.com/wire/US/ap20010911_1453.html). Senators and members of Congress joined in: Senator John Warner of Virginia referred to �our second Pearl Harbor,� Senator Hagel of Nebraska called the attacks �this generation�s Pearl Harbor� (Honolulu Advertiser, September 12, 2001, A-1). And it was not only Americans who made the analogy. CNN reported that the External Relations Commissioner for the European Union, Chris Patten �compared the attack with that deployed by the Japanese at the U.S. naval base Pearl Harbor in 1941,� quoting him to say, �This is one of those few days in life that one can actually say will change everything.� (www.cnn.com/2001/WORLD/europe/09/11/trade.centre.reaction).

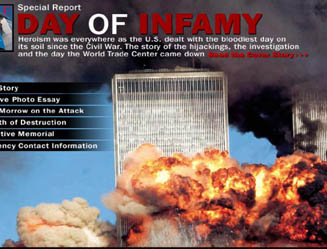

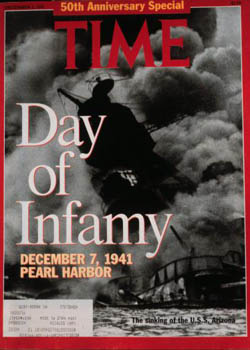

USA Today ran its account of the attacks under the front-page headline: �America recovering from ‘the second Pearl Harbor’� (Honolulu Advertiser Sept 12, 2001, A-1). Indicative of other echoes of Pearl Harbor in 9-11 reporting, the term �infamy� or �day of infamy� also appeared in many accounts, redeploying the phrase first used by Franklin Roosevelt in his declaration of war speech the day after Pearl Harbor (when his reference was actually �date that will live in infamy�). Time magazine titled its special issue on the attacks simply, �Day of Infamy�. The Honolulu Advertiser�s headline story the day after already referred to Pearl Harbor as �the other day of infamy� (�Surprise act of war invokes specter of other day of infamy� September 12, 2001, A-1).

But at this early stage, media commentators and ordinary people groped to find ways to make sense of these events. Americans felt they were at war, but did not know with whom. Even calling the attack and its aftermath �war� stretches the usual meanings of �war� in which known combatants face each other on battlefields. In the weeks and months following September 11, national ceremonies of remembrance became important occasions for representing the 9-11 attacks in the framework of the nation�s history of warfare. In these contexts, references to Pearl Harbor proved especially useful as symbolic linkages between the still nebulous and contested �war on terror� and World War II, America�s �good war� (Terkel 1984). References to Pearl Harbor and World War II attempt to interpret unimaginable events in terms of familiar models, known historical patterns.

2001 was also the 60th anniversary year of Pearl Harbor, commemorated just three months after September 11. At that time the Honolulu Advertiser ran a series of articles comparing the two events. The headline �Two Defining Moments, One Common Resolve� appeared over a photographic collage juxtaposing the wreckage of the WTC with the wrecked hulk of the USS Arizona (with the dates Dec 7 � Sept 11 superimposed). Even as the parallel was becoming routinized through this kind of media representation, commentary continued to describe the comparison as problematic. In an article accompanying the headline about �two defining moments,� editorial writer John Griffin wrote that, �Certainly the 9/11 attacks should not be called �a new Pearl Harbor,� because the differences in methods and civilian slaughter need to be emphasized.�(Honolulu Advertiser, December 1, 2001, B1). Having noted this qualification, however, Griffin went on to derive �some common lessons and cautions from the two tragedies,� noting that both events ended a period of �isolationism� and concluding that �Maybe we can even coin some new slogan for the ages: �Remember Pearl Harbor. Remember Sept. 11�. For they are related.� (B4)

But, like Griffin, other writers noted that comparisons with Pearl Harbor were partial and inadequate at best:

Even if Sept. 11, 2001, was not our deadliest day, it was surely our worst. Americans talked of “a second Pearl Harbor” and “an act of war,” but the comparisons faltered.

This time it was civilians dying in the nation’s political and financial centers, not soldiers and sailors in a distant Pacific territory. This time the targets were not outdated battleships, but buildings familiar to every schoolchild.

And if this really was war � 86 percent of Americans in a USA Today/CNN/Gallup Poll Tuesday said it was � who was the enemy? What did he want? When was the next battle? (Honolulu Advertiser, September 12, 2001, A-1).

I want to suggest two factors that contribute to the perception of parallels between these events. In both cases (1) visual images condense the significance of the larger events in single, stark moments of destruction, and (2) narratives of war represent complex events in simple story-lines of: surprise attack, catastrophic destruction, and collective national response (unity in the face of attack). On the one hand, visual images condense stories in often striking, memorable images. And other, more discursive forms of narrative expand the social and moral meanings of those images through storytelling of all kinds.

Visualizing the Past: Flashbulb Images

Pearl Harbor has been represented for Americans for more than sixty years in photographs of exploding and burning battleships; so September 11 has come to be represented in photos and videos of the burning twin towers of the World Trade Center. In both cases, visual images of destructive attacks capturing the actual moments of death and destruction have come to stand in for larger historical events, for �turning points in history.� As evidence of the force of the images of exploding battleships at Pearl Harbor, they have continued to be reproduced throughout the postwar period, reaching a crescendo of sorts during the 50th anniversary of the bombing in 1991 when they appeared in many magazine and newspaper publications, such as the cover of Time magazine. The same image, of the listing and burning ship USS Arizona, appears on the front page of the official brochure handed out at the national memorial in Honolulu.

By 2001, the evolution of technology meant that Americans not only saw images of the attacks, they saw them as they occurred, transmitted in televised accounts that now constitute a densely documented video record of �history.� In addition to the sheer magnitude of destruction and death at the Trade Center, one reason that most people think of that site as representing September 11 (rather than the Pentagon or the Pennsylvania crash) is that the New York attacks produced a longer sequence of events leading from plane crashes to explosions, fire, and ultimately collapse of the towers. These events produced a vivid photographic and video record which, in turn, has been reproduced and circulated widely in media accounts, making images of the twin towers the signature icons of September 11, just as burning battleships are the icons of December 7th.

As catastrophic events that were quickly broadcast to national audiences through electronic media (radio in 1941; television and internet in 2001), Pearl Harbor and September 11 share the distinction of being among a handful of historic moments regarded as turning points in lives and histories. Appropriately, psychologists have coined the term �flashbulb memory� for memory of momentous events such as these�events sufficiently important to rivet the attention of an entire society, leading people to remember where they were when they first heard the news (Neisser 1982; Sturken 1997). For Americans who came of age in the mid-twentieth century, Pearl Harbor was the most important �flashbulb memory.� For Americans at the turn of the century, it is now September 11. In both cases, the metaphor of �flashbulb� suggests the role played by visual images in signifying memory of more complex events.

But what do these images mean? Obviously they mean different things to different viewers. For many Americans the horrific scenes from the World Trade Center heightened a sense of awareness of membership in a national community under atttack, marking a new feeling of vulnerability in a changed world. Similar sentiments have been attributed to Americans of 1941 and 1942, upon viewing images of exploding ships in Pearl Harbor. In writing about the role of photography in World War II, Susan Moeller (1989) noted that photos of exploding and burning battleships became the defining images of Pearl Harbor for a national population going to war . These images brought home all the anxieties of a world going up in flames�just the kind of world at risk that demanded U.S. mobilization.

Narrating the Nation

The meanings of such historic images are expanded in stories that locate them in scenes that become moral dramas, embedded in wider historical contexts, linking events with implied causes and consequences. In asking about the cultural significance of historic events or �flashbulb memories,� we can ask what kind of stories they evoke. In so far as �Pearl Harbor� is already coded as one of the mythic stories in American history, invoking it as an analogy for September 11 mobilizes a pre-formed narrative that provides a framework for interpreting events that continue to elude understanding. Popular books and films that have retold the Pearl Harbor story to American audiences over the years typically represent the event in terms of an elemental, even mythic narrative structure that begins with (1) a surprise attack, causing (2) dramatic death and destruction, leading to (3) a determined response from a unified nation. As argued elsewhere, even when documentary filmmakers have set out to retell the story without recourse to �Hollywood� images or propaganda, they end up reproducing the same elemental narrative (White 2001), a structure that represents events as a moral story with actors embodying committed citizen subjects.

In summarizing these elements of the Pearl Harbor story, it is important to note that the meanings of Pearl Harbor for Americans are neither static nor singular�they have evolved throughout the postwar period and continue to be contested. For example, the significance of Pearl Harbor for many Japanese Americans, who endured racial discrimination and internment at the hands of a government unable or unwilling to recognize their loyalty to the nation, has emerged in recent years as a more important part of Pearl Harbor�s public memory.

Whereas the images of exploding battleships and the burning twin towers capture the climactic moments of destruction, references to Pearl Harbor contextualize the September 11 attacks by locating them in a broader scenario of war and national history. Both events begin with �surprise� attacks represented as particularly �evil� because of their assault on unsuspecting targets. Even though the Pearl Harbor attack was executed against armed forces that had been on high alert for weeks expecting the outbreak of war in the Pacific, the �surprise� or �sneak� attack on Sunday morning, is always represented as a kind of attack on innocents, on unsuspecting young men sleeping or at play or prayer. Popular cultural narratives of Pearl Harbor typically create images of innocence in ways that amplify the vulnerability of men dying at the hands of the attacking force. See Turnbull (1996) for discussion of the strategies of personalization adopted at the USS Arizona Memorial museum to render the attack in human and emotional terms.

The �sneak attack� label, however contested it may be, expresses the dominant American perspective on the attack, revealing some of its cultural and psychological meaning for Americans. It is this aspect of the surprise attack that earned the bombing of Pearl Harbor Franklin Roosevelt�s epithet, �Day of Infamy��a label also quickly applied to the attacks of September 11, as noted earlier. In the case of the Pearl Harbor attack, the Associated Press put out a press release a week after the bombing, that began �Born last Sunday in Japan�s treacherous attack on Hawaii, the phrase �Remember Pearl Harbor,� has overnight become the battle cry of the nation.� As a �surprise� attack, the Pearl Harbor story told in popular accounts has the effect of stripping away the wider context for the Japanese attack, the decades long clash centered on Asia, of the US and Japan. The story focused only on the events of the attack itself and the violent death of Americans killed that day. The most popular book on the attack, Walter Lord�s Day of Infamy, is essentially the story of events unfolding on the day of the attack, as told through the stories of survivors. This type of �experience-near� narrative, although an effective literary device for telling engaging stories, precludes a wider lens that might place the attack in a longer historical perspective. Occasional efforts to widen (or lengthen) the Pearl Harbor story by adding reference to the conflict of colonial powers in Asia that pressured Japan have met with resistance. For example, a documentary film that showed at the official memorial to Pearl Harbor was severely criticized for characterizing Japan as having its �back against the wall.� Similarly, efforts to widen the lens of public attention on the September 11 attacks by discussing American policies and actions in the Middle East, have also met with protestations that they demean the memory of those who died that day. For example, Rudolph Giulani, former Mayor of New York City, returned a check for $1 million given by a Saudi Prince because the Prince, in a letter to the Mayor, encouraged efforts to examine the conflicts that provoked the attacks.

If images of destruction were all there are to the Pearl Harbor story, we might ask why it has become such an oft-repeated part of American history. Those images, after all, seem to be only about defeat, about a military force caught unprepared at the hands of an apparently superior enemy. There are at least two dimensions of the story that construct a more positive story�one with a moral imperative. On the one hand, acts of heroism emerge in the context of the battle, signifying the patriotism of citizen subjects. Even if the battle was lost, individual acts of bravery personify citizens willing to sacrifice themselves for the nation. Secondly, and more importantly, the larger Pearl Harbor story does not end on December 7. It begins there, but ends with the recovery and response of a nation that unites to fight a prolonged war ending in ultimate victory. Even though the visual images only record a kind of cataclysmic defeat, resulting in the death of thousands of Americans, the invocation of �Pearl Harbor� calls up a longer story, one that ties the defeat to a national response leading to victory in the war.

Here the metaphor of �awakening� conveys the sense of an isolationist nation stirred to action while �sleeping� (just as the U.S. battleships and their crews were �sleeping� in Pearl Harbor on Sunday morning, December 7). The metaphors of sleeping and awakening have also been extended to September 11. For example, on Veterans Day, November 11, 2001–just two months after the attack�a former Army chief of staff and veteran of World War II, Korea, and Vietnam speaking at the national veterans cemetery in Honolulu used the metaphor of �sleeping giant� to refer to America prior to September 11. This image, commonly used to describe the state of unpreparedness prior to the Pearl Harbor attack, works pragmatically to signal the need for a similar resolve to win the war on terror, just as the U.S. had won the second World War.

�Weyand, a former Army chief of staff who served in World War II, Korea and Vietnam, said America should never again take some sort of strange pride in being regarded as a “sleeping giant,” because the cost of each awakening “has been paid in the blood and lives of too many of the American veterans whom we honor this morning.”

. . .

Dozens queued up to shake the hand of the 100-year-old Steer, who sat in a wheelchair, the French Legion of Honor and the U. S. Pearl Harbor Survivors decorations hanging from ribbons around his neck.

Both attacks, Steer said matter-of-factly, were “both very clever military actions, and very successful, very well planned. We let our pants hang out a little. They surprised us completely and they are still surprising us.� By invoking images of a war that had also begun with a catastrophic defeat sixty years ago, but had been won decisively, American commentators and audiences could construct an optimistic frame for the 9-11 attacks. At the same time they could enunciate an idealized image of national community, transposed from the dominant national narrative of Pearl Harbor.

And just as the visual resonance of smoking towers and burning battleships might evoke comparisons with World War II, another visual image emerged the very next day that summarized a mood of patriotic resolve. A photograph of firemen raising an American flag on a tilting pole in the middle of debris from the collapsed towers quickly became a signature image for the World Trade Center attacks. This image graphically reproduced the most circulated image from the Pacific War: that of U.S. Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima (Bradley and Powers 2000). The image of Marines pushing up a makeshift flag pole on Iwo Jima has had a long and prolific history in American popular culture, generating countless copies and now rendered in statues large and small, including the official U.S. Marine monument to the Pacific War in Washington D.C. (Marling and Wetenhall 1991). The image of firemen hoisting a flag amidst the destruction of September 11 not only resonated visually with the Iwo Jima photo (the WTC pole even tilted at an angle much like that of the pole righted by Marines in 1945), it could tap into the narrative of victory emerging from costly battles, signified by the actions of men displaying their determination to �keep the flag flying� in the face of violent warfare. The substitution of firemen for Marines says much about the different kinds of �wars� represented in these photos, as well as about the way in which police and firemen stand in for soldiers in representations and remembrances of the World Trade Center attacks.

It is this triumphal dimension of the story, about a massive collective response, personified by heroes such as the Marines and firemen raising the flags, that underlies the usefulness of Pearl Harbor as a narrative of the nation, of a nation willing and able to unify behind a war effort. As a story of recovery from defeat through the actions of citizens willing to sacrifice for the nation, Pearl Harbor is a parable of patriotic subjectivity. Commentators who referred to Pearl Harbor in the first moments of reporting on September 11 often commented about this aspect of the Pearl Harbor narrative. A newspaper article the next day observed that �In one sense, memories of Pearl Harbor offered hope,� quoting former Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger to the effect that �Pearl Harbor brought us together to face a problem. Maybe this can do the same.� (�America recovering from the �second Pearl Harbor�,� Honolulu Advertiser, September 12, 2001). Very similar remarks were made by visitors to the Arizona Memorial the day following the attacks, reported in a newspaper story in The Honolulu Advertiser. Even though the memorial was closed on September 12, for security reasons, Honolulu reporters sought out visitors there to explore thoughts about symbolic associations of the two events. Army Col. James C. Rasnick, was quoted as saying, �It [Sept 11] is a wake-up call, just like it [Pearl Harbor] was . . . They�ve awakened a sleeping giant.� (Gordon, Cole and Blakeman, Honolulu Advertiser, September 12, 2001). This dimension of the story�of a nation galvanized to fight in the face of adversity�now underwrites public support for war in the Middle East, first in Afghanistan and then Iraq (even though there is no direct evidence of complicity of Iraq in the September 11 attacks).

The narrative of surprise attack and mobilization to fight a war is not just a story told to represent past events. From 1941 to 1945 the image of Pearl Harbor was widely circulated (in posters, songs, newsreels, and so on) to stir a nation. Calls to actively �remember� the bombing were part of an organized campaign to generate a collective resolve to fight a war; to mobilize a national population. Just as the mythic story of Pearl Harbor could be used to engender patriotic responses needed to fight a war, so the comparison in 2001 is used to evoke similar sentiments today. These uses of the analogy between Pearl Harbor and 9-11 are especially evident in speeches made during national ceremonial occasions where ritual practices routinely recall the sacrifices of a nation�s soldiers as a way of expressing sentiments of patriotic loyalty. For example, in a speech given by President George Bush on Pearl Harbor Day, he compared Pearl Harbor and September 11 in precisely these terms:

On the morning of December 7, 1941, America was attacked without warning at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, by the air and naval forces of Imperial Japan. More than 2,400 people perished and another 1,100 were wounded, triggering our entry into World War II.

Today, we honor those killed 60 years ago and those who survived to fight on other fronts in the four succeeding years of world war. We also remember the millions of brave Americans who answered our country’s call to the battlefield, to the factory, and to the farm, remembering Pearl Harbor by their deeds, their devotion to duty, and their willingness to fight for freedom. The attack at Pearl Harbor fired the American spirit with a determination that freedom would not fall to tyranny; and the United States and its allies fought to victory, preserving a world in which democracy could grow. The tragedy of December 7, 1941, remains seared upon our collective national memory, a recollection that serves not just as a symbol of American military valor and American resolve, but also as a reminder of the presence of evil in the world and the need to remain ever vigilant against it.

Now, another date will forever stand alongside December 7 — September 11, 2001. On that day, our people and our way of life again were brutally and suddenly attacked, though not by a complex military maneuver, but by the surreptitious wiles of evil terrorists who took cruel and heartless advantage of the freedoms guaranteed by our Nation. Their target was not chiefly our military, but innocent civilians. We fight now to defend freedom, secure civilization, and ensure the survival of our American way of life. (George W. Bush, Jr., National Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day Proclamation, December 7th 2001).

As we fight to defend what we believe is right, we remember the sacrifice of those who have gone before us — not only the heroes of Pearl Harbor but all the men and women of the greatest of generations

Memorializing the Nation

Constructing images of patriotic citizenship, of the strong identification of ordinary people with the nation and their willingness to sacrifice themselves for its ideals, has long been the focus for national ceremonies of remembrance. In the United States, such occasions are marked on November 11, Veterans Day, and in the spring on Memorial Day�both days set aside to honor those who have fought (and died) in the nation�s wars. To these, we may add Pearl Harbor Day, December 7th and now September 11. Although not a national holiday, Pearl Harbor Day is a national day of remembrance marked with ceremonies and widespread media attention each year.

Both Pearl Harbor and September 11 are among the most densely represented events in American history. Within hours of the 1941 attack, newspapers and radio stations spread word of the bombing. President Roosevelt�s speech to Congress was carried by radio throughout the nation. Within two weeks, Life magazine ran a photo spread of the attack. In addition to newspapers, magazines, and radio, the Pearl Harbor story circulated widely through the increasingly powerful technologies of newsreels and films.

In addition to newspapers, magazines, and exhibits, representations of September 11 have been amplified through today�s more powerful technologies of communication. The events of September 11, after all, were viewed even as they were happening by millions of people watching in horror on their televisions. The World Trade Center catastrophe has been recorded in an unprecedented number of photographs, videos and media programs. A television documentary about the WTC attacks titled �In Memoriam: New York City, 9/11/01� includes video footage shot by 118 people in the vicinity of WTC the morning of the attack, as well as video from 16 news organizations. (See �A Mayor�s Recollections of an Unforgettable Day� (New York Times May 12, 2002) The producer, HBO, collected close to 1,000 hours of film and tape for the project. That film begins with the assertion that Sept 11 attack was �the most documented event in history.�

As an indication of the degree of self-consciousness surrounding calls to remember Pearl Harbor, researchers at the Library of Congress led by folklorist Alan Lomax immediately began a nationwide project to record the reactions of ordinary people. Beginning the day after, they ultimately produced volumes of tape-recordings now held at the Library of Congress� American Folklife Center. In light of this historic precedent, staff at the Folklife Center issued an urgent call over the internet on September 12, calling for participation in a similar nationwide project to record responses to 9-11, now called simply the September 11 project. (See: http://www.loc.gov/folklife/nineeleven/nineelevenhome.html )

These kinds of memory project find a more solid and enduring expression in public spaces dedicated to war memory�cemeteries, monuments, memorials, and museums. Such spaces inscribe the past in architectural and discursive forms of all kinds, providing not only visual reminders, but creating public spaces for collective practices of remembrance (Young 1993). Whereas events coded in cemeteries and monuments are always at risk of fading into the forgotten past, they also provide material and symbolic resources for the ongoing reproduction of collective memory.

Sacred Ground: Pearl Harbor and the World Trade Center

At both Pearl Harbor and the World Trade Center, rescue workers attempting to recover bodies soon realized that most of the bodies would never be recovered. They had simply disappeared in the force and intensity of explosions and physical collapse. At Pearl Harbor, 1177 men died in a massive explosion of the battleship USS Arizona, about half of the total killed in the entire attack. It is for that reason that the national memorial to the Pearl Harbor attack is called the USS Arizona Memorial, and is built spanning the remains of the sunken battleship at the location where it was moored on December 7, 1941. At the World Trade Center, where more than 2,800 people died in the September 11, only about 1100 have been identified. The remainder of the victims disappeared without a trace.

Thus, in radically different environments, both the USS Arizona and the World Trade Center have become cemeteries and shrines to the dead and missing. They have become �sacred ground� and host to ritual practices that express reverence for those who died there (Linenthal 1993). And people did not only die at Pearl Harbor and the World Trade Center, they died violent deaths as citizens or residents of the United States. Thus, remembering the dead becomes a task for the nation, a focus for imagining national community. The significance of these places as sites of national memory is perhaps more evident in the case of Pearl Harbor, given the military status of the dead, who perished on a naval base in the opening event of a conventional war. Those individuals are now listed on the wall of the USS Arizona Memorial, with indications of rank and military service. It is virtually certain that whatever design emerges for the memorial complex at the WTC, the names of all 2800 of the dead will be prominently inscribed. For example, one proposal for a design that entails a wide corridor running east and west through the site, would have rows of signposts along the walkway, each bearing the name of one of the deceased.

But elements of the nationalization of memory are also evident at the World Trade Center, even though several hundred of the victims were not citizens of the United States. This is particularly evident in the ritual practices that have marked various phases of the recovery effort. For example, during a ceremony conducted to mark the end of the clean-up phase in May 2001, an empty stretcher with a flag draped over it symbolized the victims whose remains have not been recovered. It was carried out of the pit by firemen, police, and construction workers, and was followed by the trade center’s last steel beam, loaded on the back of a flat-bed truck and draped in black cloth and flag. The ceremony was punctuated by bagpipe music and patriotic songs such as �God Bless America�.

At both Pearl Harbor and the World Trade Center, questions of how to memorialize the dead have led to debates about what would be most appropriate for those who died. Even though there was no clear consensus about whether or how to construct a memorial in the years following the bombing, by the mid 1950s fundraising was underway for a memorial that would be dedicated in 1962. [Note: one important issue of difference: payment to survivors, court cases, big settlements pending in 9-11.]Today, the USS Arizona Memorial is a national historic landmark and shrine and has become the institutional center of Pearl Harbor memory (Slackman 1986). Managed by the National Park Service in cooperation with the Navy, the Memorial is the most frequently visited tourist destination in Hawai’i, with nearly 1.5 million visitors each year. The US Navy and the National Park Service conduct memorial services at the Arizona every Memorial Day and December 7th (the day of the bombing). The Navy also conducts enlistment ceremonies and hosts official visitations at the Memorial.

Whereas the production of national memory at the Arizona Memorial is now quite routinized (even if still contested and evolving), the meanings of the World Trade Center site remain raw and undigested. Ritual practices conducted to memorialize the dead have had to be invented. There simply is no precedent. Whose meanings, emotions, and perspectives will be accommodated in such a diverse and contentious universe as New York City? From September 11 onward, groups of people big and small have engaged in spontaneous acts of remembrance and commemoration. One of the functions of ritual and ceremony is to create a context in which meaning can be produced for audiences who feel connected to the places and events at hand.

Within days, even hours of the attack, work began on plans and proposals for various kinds of memorial. The Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for example, wrote an editorial suggesting that the last piece of wall left standing at the site and evident in photographs be preserved as an iconic reminder of the destruction. That jagged section of wall, with its eerie similarity to the listing conning tower of the USS Arizona, and even the skeletal remains of the atomic bomb dome in Hiroshima, now sits in storage awaiting plans for memorial architecture.

The City of New York commission charged with reviewing plans for redesigning and rebuilding the WTC site has overseen a contentious debate about the nature and degree of memorial space to be constructed there. As the process moved forward, families of those killed in the attacks have been extensively involved in the consultation process. Some wanted the entire 16-acre site to be used for a Memorial, seeing a return to commercial use as a denigration of the memory of those who died (see �Blueprint for Ground Zero,� New York Times, May 4, 2002). All of the proposals reviewed initially set aside approximately seven acres of the 16-acre site �as sacred ground� to provide a way to �incorporate some tangible reminder of the towers themselves into the memorial design.� The remaining 9 acres would be rebuilt as commercial space. The design recently selected, produced by the German firm Studio Libeskind, calls for a 4.5 acre memorial park 30 feet below street level preserving the footprints of both original towers.

As is the case for the USS Arizona Memorial, the focal elements for a World Trade Center memorial will be the people who died there and those who survived. The deaths of thousands have already been lamented in myriad ways (such as in the daily pages of the New York Times that for months published biographical sketches of lives cut short, told in touching personal terms elicited from loved ones). This personalization of loss is a tactic of remembrance characteristic of national memories of war generally, evident in literatures and films of war that humanize the inhuman by telling the stories of individuals caught up in deadly events. Phyllis Turnbull has described this approach in the small museum of the Arizona Memorial, with its preference for displaying letters home and other memorabilia from the doomed crew of the USS Arizona (Turnbull 1996). The personalization of historic events in this way heightens their moral and emotional significance, working not only to nationalize memory but to emotionalize the nation.

Conclusion

In this paper I have focused particularly on the ability of war memory and memorial practices to create powerful forms of national identification. Everywhere the experience of war is enlisted to the cause of nationalism, to mold personal subjectivity as part of an imagined national community mobilized for war. The great irony or contradiction of the era of globalization at this turn-of-millennium moment is that the very forces that traverse and dissolve national boundaries through economic and technological flows have served to accentuate and deepen nationalisms and movements of cultural revitalization. Nowhere are the boundaries of the nation more clear and inviolable than in its sacred sites�spaces that mark the death of citizens and in so doing mark a kind of limit of national subjectivity. Burial sites of violent death and loss become inviolable spaces that link personal memory with national history. In particular, collective rites of remembrance work to meld the personal and intimate with the collective and public.

If the history of Pearl Harbor memory is any indication, we may predict that September 11 will continue to be represented in new and revised forms as it is adapted and (re)circulated in future years. Representations of Pearl Harbor have evolved steadily throughout the 60 years of postwar history, marked by the release of the feature film Tora! Tora! Tora! in 1970 and reaching a peak during the fiftieth anniversary in 1991 (Dingman 1994; White 1997). Whereas some might have expected that interest in Pearl Harbor would wane as the war generation ages, 2001 witnessed an upsurge of renewed interest as Disney Studios released it�s summer �blockbuster� film Pearl Harbor. Aimed at younger movie-going audiences, that film showed in more than 3,200 cinemas across America when in opened. And it stimulated no less than 22 television and documentary films focusing on various aspects of the �real story,� suddenly of interest because of the Hollywood publicity machine (White 2002).

Having described some of the ways that Pearl Harbor has been invoked to interpret and define September 11, it is important to also note that September 11 has had an important effect on the meanings of Pearl Harbor and other previous wars, especially Vietnam. Senator John McCain, on day of the memorial service marking the end of the recovery effort at the WTC observed that many who had opposed the Vietnam war have found a new �compact with their country.� He hoped that the �ghosts of Vietnam� might at last be �put to rest.� 2001, with the release of the Disney film Pearl Harbor and its spin-off documentaries, was already a year in which Pearl Harbor memory was again re-inscribed in American popular culture. Shortly after September 11, the Honolulu media carried stories about visitors to the Arizona Memorial finding new meaning in that site, seeing the call to �be prepared� as once again taking on renewed significance.

The heavy inscription of Pearl Harbor and other WWII images in American representations of September 11, as well as the absence of reference to the atomic bombings, make sense if we consider that acts of representation and remembrance are concerned to do something�in this case to validate a sense of national purpose in the face of devastating attack. [A possible place where you might wish to develop this slightly: the specific mobilization of the nation for a series of wars, even pre-emptive wars, militarization on a global scale, the expansion of US military and other power etc.] Yet, in this age of global media flows, we may wonder how it is that intensely national images produced by American media and consumed by American audiences can have the effect they do. In this paper I�ve suggested that the ability to recontextualize conflict in the frameworks of memory growing out of previous wars continue to shape the meaning of events according to the familiar scripts of global conflict among nations.

Given that the Pearl Harbor attack, as a focus for American propaganda and resolve, proved to be such a liability for the Japanese during the war�providing a symbolic focus for American rage and resolve, one wonders if those planning the terrorist attacks of September 11 were aware of Pacific War history. On the other hand, if the aim of the attacks was to create the symbolic conditions of war (rather than to win a war)�to provoke reactions that manifest a vision of global conflict between Islam and the West, then attacks that create an environment reminiscent of World War II could be said to have succeeded, possibly beyond the dreams of those who perpetrated them.

REFERENCES

Bradley, James, and Ron Powers

2000 Flags of our fathers. New York: Bantam Books.

Chomsky, Noam

2002 9-11. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Dingman, Roger

1994 Reflections on Pearl Harbor Anniversaries Past. The Journal of American-East Asian Relations 3(3):279-293.

Lifton, Robert Jay and Greg Mitchell

1995 Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial. New York: G.P. Putnam�s Sons.

Linenthal, Edward, and Tom Engelhardt, eds.

1996 History Wars: The ‘Enola Gay’ and Other Battles for the American Past. New York: Henry Holt and Co.

Linenthal, Edward T.

1993 Sacred Ground: Americans and Their Battlegrounds. Rev. ed. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Marling, Karal Ann, and John Wetenhall

1991 Iwo Jima: Monuments, Memories, and the American Hero. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Un iversity Press.

Moeller, Susan D.

1989 Shooting War: Photography and the American Experience of Combat. New York: Basic Books.

Neisser, Ulric

1982 Memory Observed: Remembering in Natural Contexts. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

Slackman, Michael

1986 Remembering Pearl Harbor: The Story of the USS Arizona Memorial. Honolulu: Arizona Memorial Museum Association.

Sturken, Marita

1997 Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Terkel, Studs

1984 “The Good War”: An Oral History of World War II. New York: Pantheon Books.

Turnbull, Phyllis

1996 Remembering Pearl Harbor: The Semiotics of the Arizona Memorial. In Challenging Boundaries: Global Flows, Territorial Identities. H.A. Jr. and M. Shapiro, eds. Pp. 407-433. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

White, Geoffrey M.

1997 Mythic History and National Memory: The Pearl Harbor Anniversary. Culture and Psychology, Special Issue edited by James Wertsch 3(1):63-88.

� 2001 Moving History: The Pearl Harbor Film(s). In Perilous Memories: The Asia-Pacific War(s). T. Fujitani, G. White, and L. Yoneyama, eds. Pp. 267-295. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

� 2002 National Memory at the Movies: Disney’s Pearl Harbor. The Public Historian in press.

White, Geoffrey, and Jane Yi

2001 December 7th: Race and Nation in Wartime Documentary. In Classic Whiteness: Race and the Hollywood Studio System. D. Bernardi, ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Young, Donald J.

1992 December 1941: America’s First 25 Days at War. Missoula, MT: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co, Inc.

Young, James E.

1993 The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning. New Haven: Yale University Press.