Abstract: Singapore earned early plaudits for its management of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the government’s failure to pay attention to the health of the country’s sizable foreign worker population and its refusal to heed the repeated warnings from infectious disease experts and advocacy groups has led to a major outbreak in cramped dormitories and a lockdown of the entire country. Later, as caseloads dropped and citizens received cash handouts, the ruling People’s Action Party staged an election in the hopes of receiving an overwhelming electoral mandate, even as infections remained a serious public health concern. The opposition received its best-ever result, further calling Singapore’s elitist party-state governance model into question.

In early March 2020, basking in international praise for its early “gold standard” response to COVID-19, Singapore’s rulers prepared to hold parliamentary elections. Of course, the continued dominance of the People’s Action Party (PAP), which has been in power since 1959, was a foregone conclusion. Yet, this election seemed to offer an opportunity for Prime Minister and PAP Secretary-General Lee Hsien Loong to pass the baton to a new generation of ministers. As one local commentator observed, “…Lee regarded the COVID-19 crisis as a political transition opportunity as much as a public health crisis. While other heads of state have prominently fronted their country’s public engagement, Lee slid into the background, forcing several ministers from the relatively inexperienced 4G cohort to take control” (Vadaketh, 2020). In those halcyon days, government officials and media outlets were still telling people not to wear masks unless they were sick, and threatening construction companies who sent their foreign employees to hospitals for COVID-19 tests due to a lack of supplies and an explicit choice to prioritize the rest of the population.

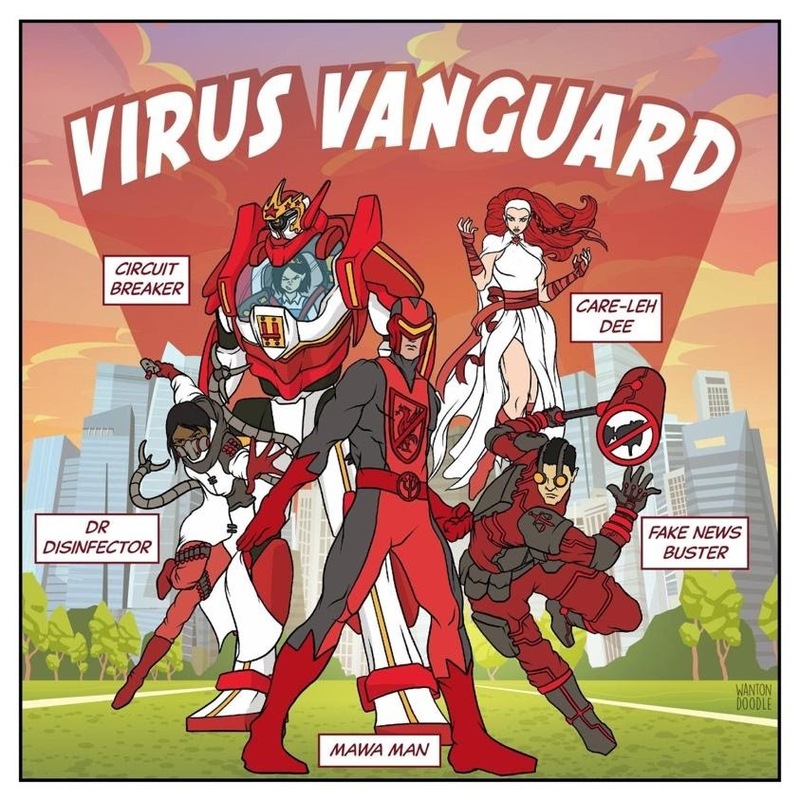

Superheroes removed after public backlash |

The first outbreaks among foreign workers were controlled. Still, infectious disease expert and chairman of the opposition Singapore Democratic Party, Dr. Paul Tambyah, cautioned that ring-fencing infected migrant workers within their massive dormitories could lead to “the Diamond Princess all over again” (Han, 2020). His reference to the quarantined cruise ship docked outside Yokohama proved apt. Indeed, only days after the election planning began, COVID-19 ripped through dormitories so cramped and squalid that even the Straits Times, the party-state mouthpiece positioned as the newspaper of national record, reported that “the rooms are infested with cockroaches and toilets are overflowing. Workers have to queue for food with no social distancing measures to keep them apart” (Lim, 2020). Overnight, dozens of disease-stricken dorms housing a total of over 300,000 workers, mostly from India, Bangladesh, and China, became prisons, with most residents barred from leaving their quarters, while still uncertain if their roommates were infectious. It took further days of outcry from concerned citizens and members of civil society before those laborers deemed “essential” by a government task force were evacuated and temporarily housed in vacant parking lots and floating barges.

Outside the dorms, as cases spiked in what official statistics classified separately as the “community”, the government’s initially relaxed and confident handling turned incoherent and draconian. The PAP regime hastily implemented a nationwide lockdown, euphemistically dubbed a “Circuit Breaker”, shuttering businesses, mandating mask wearing, and forbidding nearly all forms of personal visitation on threat of high fines, six months in prison, or deportation and permanent re-entry bans for non-citizens. Emergency cash hand-outs went out to support those affected, although much of this was routed through employers. Even after such a shocking turnaround, Wong claimed, incredibly, that Singapore had not changed its strategy or approach in the battle against COVID-19 (Sin, 2020). Meanwhile, in what was a likely a world-first, Singapore’s judiciary delivered a death penalty sentence via a Zoom call, perhaps suggesting the need for science-fiction writer William Gibson to update his 1998 characterization of Singapore in “Disneyland with the Death Penalty”, a WIRED cover story which got the magazine banned for years (Gibson 1993).

The response demonstrated not only the cynicism of the PAP leadership, but its utter incompetence, shattering the party-state’s carefully-crafted façade of technocratic mastery. Perhaps the best that could be said of such a sorry performance is that despite the effective imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of foreign workers, the economic disruption and psychosocial devastation caused by a lockdown of nearly 6 million “community” members, and the terrifying risk posed by the ruling party’s decision to hold an election during a plague it was clearly incapable of managing, the number of COVID-19 deaths remained low by international standards, with under 30 fatalities out of over 40,000 confirmed cases by July 2020. Still, given the closely guarded secrecy of government data, whether these outcomes are proportionally any better than those of North Korea, with whom Singapore’s special blend of kitschy nepotism has more than a little in common, is hard to know for certain.

Minister for National Development Lawrence Wong, the co-chair of the COVID-19 task force, who had been praised for his clear and consistent crisis communication in the early days of the pandemic, claimed to have been blindsided by the dorm outbreak: “Unfortunately, we do not have the luxury of the benefit of hindsight… The virus is moving so quickly. If I’d known, I would have done things differently. But no one can tell the next step.” Yet, as noted by freelance journalist Kirsten Han, “you can’t have foresight for things you refuse to see” (Han, 2020).

Indeed, the first reported foreign worker outbreak occurred in February, and was effectively contained through extensive contact tracing and quarantine. However, few infection prevention measures were implemented for the rest of the dorms. The government did little beyond suggesting that foreign workers, who were not issued masks or hand sanitizer, exercise “personal responsibility” while residing in dorms housing over 10,000 men each, sleeping in rooms with 15 men sandwiched on bunk beds, using shared bathrooms, and cooking “shoulder-to-shoulder by the hundreds in mass kitchens” (Chew, 2020). This failure came in spite of persistent warnings from advocacy groups that tried to call attention to the health vulnerabilities of foreign workers (TWC2, 2020). Years earlier, a study conducted in 2017 already demonstrated that migrant workers’ work and living conditions placed them at a significantly higher risk for infectious diseases such as dengue, Zika, and tuberculosis (Sadarangani, Lim and Vasoo, 2017).

Josephine Teo, the Minister of Manpower, was asked in Parliament if she might consider offering an apology to the migrant workers “given the dismal conditions that they are currently in”. Betraying an extraordinarily flippant indifference to the structural inequality between her and her wards, who oscillated between fear of infection from their fellow dorm-mates and concern about deportation to even more chaotic circumstances, Minister Teo replied, “…I have not come across one single migrant worker himself that has demanded an apology” (Zhang, 2020).

Migrant workers’ activist who apologized to Minister Teo for wearing ironic t-shirt |

In this “Chinese family business” that passes for a city-state (Barr, 2014), it came as little surprise that Josephine Teo’s husband served as the International CEO of Surbana Jurong, a company which was tapped to handle the emergency housing and treatment facilities for newly-evacuated workers. Surbana Jurong is wholly owned by Temasek Holdings, the sovereign wealth fund headed by Prime Minister Lee’s wife, Ho Ching. After two people, including social worker Jolovan Wham, suggested in Facebook posts that these relationships just might constitute a conflict of interest, they were threatened with lawsuits by Teo, who noted that her husband was the “International CEO” of the company, not the domestic CEO, and was therefore not involved in any of these arrangements for foreign workers. Facing high legal fees and severe repercussions, Wham and the other poster retracted their posts and publicly apologized (CNA, 2020).

Leaping to the defence of his team, Prime Minister Lee declared that Singapore would not be a place where his ministers, the highest-paid in the world, would step down based on things that weren’t their fault. Singapore’s ministerial salaries are premised on the myth of a “natural aristocracy”, as famously put by Prime Minister Lee, that legitimizes extraordinarily high compensation on the basis of presumed competence. This myth follows from the 1971 statement of his father, founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, that the survival of Singapore rests on the shoulders of “some 300 key persons” in the ruling party, civil service and military, and that “if all 300 were to crash in one jumbo jet, then Singapore will disintegrate” (Lee, 1971). Whether or not the majority of Singaporeans subscribe to such a self-serving fantasy, the PAP have sustained their parliamentary supermajority for decades, effectively giving them free rein to change the constitution and raise public servant pay as they please.

If the pandemic proved that even these hyper-credentialed and highly-paid elite are not immune to bungling, it also demonstrated the impressive capacity of working-class Singaporeans to self-organise and practice solidarity. In the face of socioeconomic precarity aggravated by the lockdown, various ground-up initiatives emerged — from Facebook groups to support freelancers, to volunteer associations that directed donated laptops to low-income students who were struggling with the sudden switch to home-based learning, to campaigns to provide phone top-up cards for trapped migrant workers to call home. Social media exploded with calls encouraging better-off Singaporeans to donate their government cash pay-out to those in need.

Robot dogs enforce social distancing in parks |

In late June, despite the risk of continuing infections, the government loosened mobility restrictions enough to press ahead with elections the following month. Commentators speculated that the PAP presumed that a crisis-stricken electorate would opt for the devil they knew. After all, as Chan Chun Sing, the Deputy Prime Minister, revealed in a leaked recording of a talk to PAP cadres, the party had repeatedly profited from staging elections in the midst of crises. Throughout the brief election season, Prime Minister Lee hammered on about the necessity of the incumbent to receive a strong mandate, as if further legitimizing the faltering ruling party would be required to steer Singapore out of the crisis.

President Lee Hsien Loong (left) and his PAP suffered setback at pandemic polls |

Of course, after years of gerrymandering, state control of print and broadcast media, and the legal authority to silence its critics at will, there was no chance that the PAP would lose control of Parliament. But between the crisis and a series of emergency relief budgets that had delivered cash handouts to voters, perhaps the PAP thought they had a slam dunk case for an even more overwhelming electoral result. Alas, they were proven wrong by a careful and well-organized opposition, including a resurgent Workers Party.

Facing a more attractive, optimistic, and social media-savvy opposition, the PAP resorted to old tactics, such as race baiting and personal smears, and added new tricks, like the 2019 POFMA bill, which empowered ministers to demand the removal of any online information they deemed “false”. POFMA was passed under the pretense of protecting against foreign influence campaigns. It has since been almost exclusively used against domestic political opponents. Targets included Dr. Paul Tambyah, for remarks on what he deemed an ill-advised punitive policy by the Ministry of Manpower that discouraged employers from sending asymptomatic migrant workers for COVID-19 testing (Goh, 2020).

Despite such tactics, given the government’s bungled COVID-19 response, the opposition’s calls for accountability and a diversity of voices in parliament resonated with a more confident electorate. Although opposition parties and other groups still had to expend energy to reassure voters that their ballots were secret, and that voting for the opposition would not result in any legal repercussions, the usual atmosphere of fear and resignation no longer defined the election season. Singaporeans appeared more engaged with contentious party politics than they had been in living memory. The nine-day campaigning period saw vibrant discussion, mostly conducted online due to mobility restrictions, and a flourishing of critical commentary on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. These debates went beyond so-called ‘bread and butter’ issues to squarely address the country’s political structure and direction. Given decades of programmatic depoliticization among the populace, the wide diffusion of such discussions into the mainstream was inconceivable just five years before. Such a change is in no small part due to the emergence of a younger and more politically active generation of Singaporeans, who find it easier to acquire information and engage in debates online, and the groundwork laid by earlier waves of long-suffering activists.

Meanwhile, detached from the ground, the incumbents did not seem to realize that the dirtier they played, the more incensed voters became. A chaotic election day, featuring confused hygiene safeguards and a highly irregular snap extension of voting by two hours, resulted in 61% nationwide popular vote for the PAP, the second-lowest number since independence in 1965. Despite this relatively poor showing, the bizarre and byzantine division of constituencies allowed the PAP to walk away with 83 of the 93 elected seats. Of the ten members of the opposition Workers Party elected to parliament, Raeesah Khan, a 26 year-old self-described “intersectional feminist” won, despite having been subject early in the election season to a scurrilous police investigation for allegedly fomenting racial and religious disharmony based on a two year-old Facebook private post about the unfairness of discretionary police enforcement (George and Low, 2020).

|

After the results were announced, residents of the Workers Party’s newly won ward of Sengkang cheered from their windows, as supporters gathered at a coffee shop next to the party headquarters. Impromptu celebrations continued deep into the night, which included patriotic displays of belting out the national anthem and reciting the national pledge. Within such an unusually hopeful atmosphere, it was easy to forget that the occasion was the win of a mere 10 opposition seats in parliament.

Although some Singaporeans showed that they are ready for change in their country’s governance, sober observers should expect more of the same from an unrepentant ruling party that managed to retain its supermajority. Despite Minister for Law and Home Affairs K Shanmugam’s admission that the vote swing called for “a lot of soul searching and reflection” within the PAP (Abdullah, 2020), little looked set to change. As COVID cases in the dormitories begin to rise again right after the elections, employment regulations were amended to authorize employers to dictate the movements of their workers (HOME, 2020). In a televised press conference, Minister Lawrence Wong lectured citizens about the lack of social distancing at the opposition celebrations and warned about how it could lead to an uptick in infections, ignoring the fact that it was the ruling party that chose to call for an election in the middle of a pandemic (Channel News Asia, 2020). Given the imperiousness of the world’s longest-ruling elected party, it seemed that even the plague was not quite powerful enough to topple the unnatural aristocracy.

References

Abdullah, Z. 2020. Clear messages sent by voters in GE2020, ‘soul searching and reflection’ needed: Shanmugam. Channel News Asia, 11 July. Accessed 18 July 2020.

Barr, M.D. 2014. The Ruling Elite of Singapore. Networks of Power and Influence. I.B. Tauris. Print.

Channel News Asia. 2020. COVID-19: Second wave of infections in Singapore “preventable” if all play a part, says task force. YouTube, 17 July. Accessed 18 July 2020.

Chew, S. 2020. Migrant Workers’ Dorms Were Always Ticking Time-Bombs. Singapore’s Failure To Act Sooner Is Inexcusable. Rice Media, 6 April. Accessed 14 July 2020.

CNA. 2020. Jolovan Wham apologises over allegations of corruption against Josephine Teo. Channel News Asia, 22 May. Accessed 14 July 2020.

Goh, C.T. 2020. GE2020: POFMA correction directions ‘a complete distraction’, says SDP’s Tambyah. Channel News Asia, 6 July. Accessed 16 July 2020.

George, C. and Low, D. 2020. GE2020: Why Singapore may lose, whatever the final score. Academia | SG, 7 July. Accessed 14 July 2020.

Gibson, W. 1993. Disneyland with the Death Penalty. WIRED, April 1.

Han, K. 2020. Singapore’s new covid-19 cases reveal the country’s two very different realities. Washington Post, 16 April. Accessed 14 July 2020.

Han, K. 2020. Singapore’s migrant workers on front line of coronavirus shutdown. Al Jazeera, 8 April. Accessed 16 July 2020.

HOME. 2020. Response to Post-Circuitbreaker Amendments to the Employment of Foreign Manpower (Work Passes) Regulations — HOME & TWC2, Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics, 26 June. Accessed 18 July 2020.

Lee, K.Y. 1971. “Politics, economics, security and your future.” Address by the Prime Minister at the seminar on communism and democracy, Singapore, 28 April. Accessed 16 July 2020.

Lim, J. 2020. Coronavirus: Workers describe crowded, cramped living conditions at dormitory gazetted as isolation area. Straits Times, 6 April. Accessed 14 July 2020.

Sadarangani, S.P., Lim, P.L., and Vasoo, S. 2017. Infectious diseases and migrant worker health in Singapore: a receiving country’s perspective. Journal of Travel Medicine, 24(4). Print.

Sin, Y. 2020. Singapore has not changed approach to tackling Covid-19. Straits Times, 15 April. Accessed 14 July 2020.

TWC2. 2020. Straits Times Forum: Employers’ practices leave foreign workers vulnerable to infection, 23 March. Accessed 16 July 2020.

Vadaketh, S.T. 2020. Coronavirus: is electioneering to blame for Singapore’s teetering pandemic response? South China Morning Post, 5 May. Accessed 14 July 2020.

Zhang, J. 2020. ‘I have not come across one single migrant worker himself that has demanded an apology’: Teo. Mothership, 4 May. Accessed 14 July 2020.