Abstract: Indonesia remains the country with the largest number of Covid-19 fatalities in Southeast Asia. Observers have focused on the political impact of President Joko Widodo’s crisis management. Many argue that the pandemic has exposed the country’s democratic decline. This article focuses on the military and analyzes how the army has instrumentalized the coronavirus crisis to boost its agenda. We look into four cases of active army lobbying aimed to expand its missions beyond national defense, arguing that the army has skillfully exploited the Covid-19 crisis to reverse some key post-Suharto military reforms.

Introduction

With an official count of more than 2,500 deaths (as of June 24, 2020), Indonesia has endured the biggest Covid-19 outbreak in Southeast Asia. The government led by President Joko Widodo (popularly called Jokowi) has struggled to stem the spread of the virus and mitigate the damage in society, facing the common dilemma of balancing epidemiological risks and the economic costs of restricting people’s daily activities. The media coverage has generally been critical, exposing the problems of medical resource deficiencies, the credibility of official data on infections and deaths, and the inadequacies of top government leaders in handling the crisis.

Some observers have probed the political ramifications of Indonesia’s Covid-19 crisis. Mietzner (2020), for example, highlights democratic decline under the Jokowi presidency—noting the trend of populist polarization and the weakening of anti-corruption efforts—that has contributed significantly to the ineffectiveness of the country’s Covid-19 responses. Others have argued that the Covid-19 crisis has exposed Jokowi’s weak leadership and invigorated political ambitions of those who seek to compete in the 2024 presidential elections (Lane 2020, Sulaiman 2020, Bean 2020). Some suggest that the political rivalry between Jokowi and local leaders is reflected in their respective Covid-19 responses in a way that deepens sociopolitical polarization in the country (Warburton 2020, Hermawan 2020). In addition, pollsters find that Covid-19 has diminished public trust in the central government (The Jakarta Post 2020) and, more seriously, amplified public dissatisfaction with democracy (Indikator 2020). Thus, observers of Indonesian politics, have tried to identify weaknesses in Jokowi’s Covid-19 governance or the political effects of the government’s poor crisis management.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo |

This article examines how the military elite has instrumentalized the Covid-19 crisis to advance its institutional agenda. There are many reports about how Jokowi has mobilized the military (Tentara Nasional Indonesia: TNI) in dealing with the crisis. In contrast, here we examine how and why the pandemic has become a decisive opportunity for the military and how it is exploiting the crisis. Below, we examine TNI’s internal problems and how these have shaped military politics in pandemic Indonesia.

Surplus as Time-bomb

When Suharto’s 32 years of dictatorship ended in 1998, the TNI was under heavy pressure to drastically reduce activities outside its professional national defense duties. This role reduction, often called ‘back to the barracks,’ impacted the army most seriously, the largest among the three services, as it faced a structural crisis of losing massive extra-military positions and jobs that had absorbed army high-ranking officers during the authoritarian era. The post-Suharto army chiefs have faced expectations that they alleviate the problem of increasing numbers of surplus officers who have no jobs in the organization (IPAC 2016; Laksamana 2019). By 2018, the number of these jobless high-ranking army officers exceeded 500. An internal workshop held by the Defense Ministry in 2018, identified this joblessness as a time-bomb requiring an immediate response.

It is against this backdrop that the army under the Jokowi administration has endeavored to create positions for generals, including: the creation of a 3rd infantry division of the army strategic reserve command (Divinf-3 Kostrad) headed by a major general; a decision in 2019 to change the rank of the commanders of some sub-regional commands (Korem) from colonel to brigadier general; and the mid-2019 establishment of three Joint Regional Defense Commands (Kogabwilhan) throughout the archipelago, creating many positions for high-ranking army officers. This significant organizational expansion, however, was not enough to placate officers who resented what were seen as unfair promotions of politically connected officers. This discontent was also amplified by the prominence of national police in the country’s security arena traditionally regarded as the TNI’s turf, as symbolically seen in Jokowi’s appointments of police generals to Minister of Home Affairs, Head of the National Intelligence Agency (BIN), Head of the National Counter-Terrorism Agency (BNPT) and Chairman of the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK). In particular, many army officers interpreted Jokowi’s unprecedented appointment in late 2019 of a police general—Tito Karnavian, the former police chief—to serve as Minister of Home Affairs, managing all regional affairs and supervising local government heads down to the village level, as the coup de grace.

Army Chief General Andika Perkasa |

This inter-service rivalry fueled frustrations within the army, putting pressure on the current army chief Gen. Andika Perkasa to assert army interests. He is well connected to Jokowi’s inner circle, becoming the commander of the presidential guard in 2014, and enjoys the strong backing of his father-in-law, Lt. Gen. (ret) Hendropriyono, ex-BIN chief and a right-hand man of Megawati Sukarnoputri who is the country’s ex-president and chairwoman of the ruling Indonesian Democratic Party for Struggle (PDI-P) that has supported Jokowi’s political career. Given such strong political connections, it is natural that Andika incites jealousy among many officers, but it has also incentivized him to demonstrate the merits of having a well-connected army chief who can lobby the president on behalf of his subordinates. It is against this backdrop that some of the measures for organizational expansion discussed above were taken under Andika’s leadership after he became army chief in November 2018. “How to solve the problem of ‘5th floor’ has been Andika’s primary concern,” remarked an insider referring to the 5th floor library of the army headquarters in Jakarta where jobless officers spend the day reading newspapers.

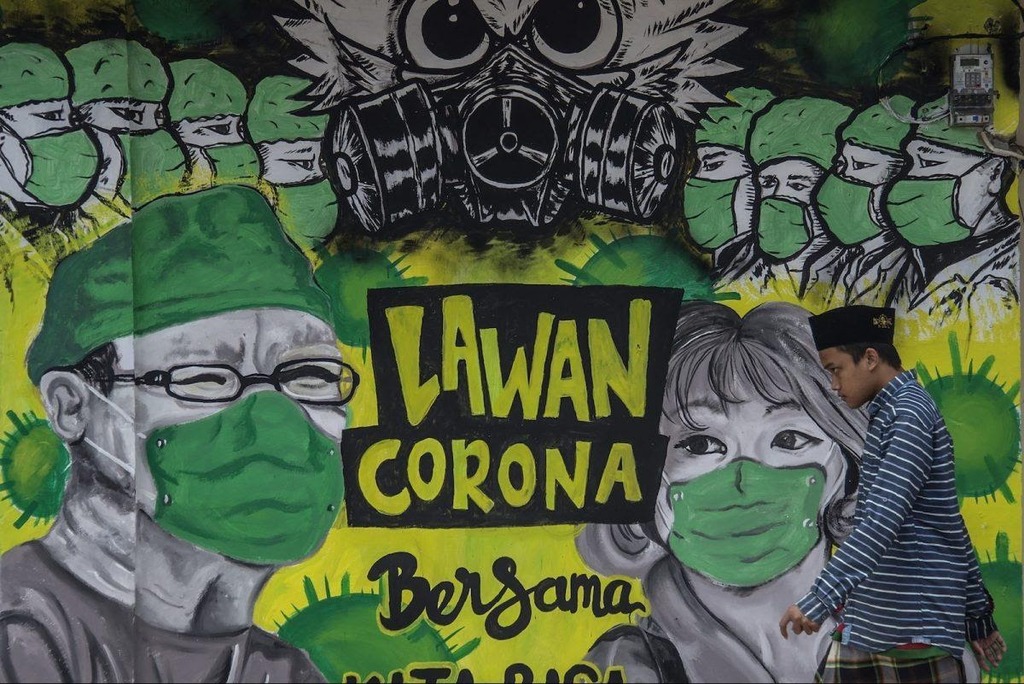

Public Health Warning Indonesia |

Fighting Covid-19

An opportunity to further expand jobs for high-ranking officers arrived with the coronavirus. When Jokowi established the Covid-19 national taskforce in March 2020, the public did not expect to see a massive influx of army officers to the taskforce both at the national and local levels. Headed by Lt. Gen. Doni Munardo, the former commander of the army special forces (Kopassus), the national taskforce supervises local taskforces, which have mobilized more than 200 military officers (mostly from the army) as deputy chiefs, creating an impression that the country’s Coronavirus management is ‘partially militarized’ (Laksamana and Taufika 2020).

Doni surprised the public when he dressed up in military uniform, and appeared at the taskforce meeting on April 27, despite the fact that the two agencies he led, i.e. the Covid-19 national taskforce and National Disaster Agency (BNPB), were civilian organizations. Doni seemingly ‘dog-whistled’ to his army colleagues that he retains his military identity and represents the army in this time of national crisis.

In parallel with the formation of Covid-19 taskforces across the country, Andika’s army conducted massive personnel changes during the middle of the pandemic crisis in early April, involving more than 280 army officers. During this reshuffle, there was a remarkable increase in the number of Korem elevated to ‘A-type Korem.’ An A-type Korem is now commanded by a one-star general whereas previously commanders held the rank of colonel. This scheme was first introduced in early 2019 and has been adopted by more than 70% (34 out of 47) of all Korems throughout the country. In 2020, the rationale for increasing the number of A-type Korems was attributed to the need to upgrade the army’s Covid-19 response at the local level.

Using the crisis as pretext, Andika’s army stealthily carried out a policy which would otherwise have invited criticism for hastily inflating the number of generals. A close look at the April reshuffle also revealed that many of these officers who were promoted to one-star generals are graduates of the military academy between 1985-1987, meaning they would retire soon. Given the big difference between colonels and brigadier generals in terms of post-retirement opportunities for income and power, it appears that Andika used Covid-19 to appease senior officers and strengthen his institutional support.

Counter-terrorism

In early May 2020, the military further moved to institutionalize its role expansion for everyday counter-terrorism operations. In post-authoritarian Indonesia, the military has played a secondary counter-terrorist role behind the police. TNI, especially the army, has longstanding ambitions to claw back a significant internal security role and has managed to exploit the Covid-19 crisis to convince Jokowi to produce a draft presidential regulation on expanding the TNI’s counter-terrorist role. The draft proposes independent TNI anti-terrorism activities beyond merely supporting the police, including territorial (regional) and intelligence operations. The draft regulation requires parliamentary approval and to help ensure passage the military intelligence body has actively lobbied lawmakers seeking their endorsement (Majalah Tempo 2020b).

The police are of course discreetly opposed to the idea of ceding counter-terrorism turf. Civil society groups have also expressed strong opposition to the draft presidential regulation, calling it an attempt to return to the authoritarian ways of President Suharto’s New Order (1967-1998). The TNI, anticipating strong public resistance to an expanded military role, has used the pandemic crisis to secure a presidential regulation rather than a politically more difficult revision of the law governing TNI. Whether the draft regulation is approved or not by the parliament remains unknown, but intensive military lobbying of parliamentarians may bear fruit as politicians may not want to antagonize the army, especially as civil society groups can’t counter with street demonstrations under current Covid-19 restrictions on large-scale gatherings.

Pancasila

In mid-May, TNI again tried to expand its role and positions outside defense-security sectors. It was a plan to involve active military/police officers in the Agency of Pancasila Ideology Education (BPIP), a new body established by Jokowi in February 2018 for the promotion of Pancasila, the state ideology; an ideology established by the country’s first president Sukarno and subsequently used by Suharto to legitimize his authoritarianism. BPIP was Jokowi’s initiative to please his patron Megawati, a daughter of Sukarno, whom he assigned as the head of the steering committee. BPIP started with no idea of involving active TNI officers in the agency as it would invoke memories of the Suharto era’s military hegemony over the state ideology. However, the draft law on Pancasila Ideology Orientation was deliberated by the parliament, and it contained a stipulation that active TNI officers could serve on the BPIP’s board of directors. To explain why TNI should be involved, a parliamentarian from the Golkar Party claimed: “Pancasila is the basis of national development encompassing various sectors, including national defense, so that we need to involve TNI” (CNN Indonesia 2020).

The government insists that the bill was prepared by lawmakers, not by the government, but this claim does little to obscure the military’s backdoor lobbying. The two main parties in parliament, i.e. the PDI-P and Golkar Party, include powerful ex-military figures, for example Megawati’s right-hand men such as Hendropriyono and former vice-president Gen (ret) Try Sutrisno, and Golkar’s secretary-general Lodewijk Paulus, the former commander of Kopassus. As seen above, Hendropriyono is in a position to give input to Megawati on behalf of the army chief Andika. Try Sutrisno, who serves BPIP as Megawati’s deputy, is also a long-time adviser for the party chairwoman who is a powerful patron of his son, Brig. Gen. Kunto Arief Wibowo who was recently appointed as chief of staff of the prestigious Siliwangi Military Regional Command that oversees West Java—a politically significant region adjacent to Jakarta. Kunto is also a brother-in-law of Gen. (ret) Ryamizard Ryacudu, another close advisor of Megawati whom she appointed as Defense Minister during Jokowi’s first-term (2014-2019). Paulus has served as Golkar’s secretary-general since 2018 and he enjoys the powerful backing of retired army general Luhut Binsar Panjaitan, Jokowi’s right-hand man who serves as Coordinating Minister of Maritime Affairs and is widely dubbed ‘prime minister.’ Importantly, Jokowi’s presidential guard is now headed by Maj. Gen. Maruli Simanjuntak, son-in-law of Luhut. Both Kunto and Maruli are ‘the stars’ of the academy graduates in the class of 1992 and well understand the frustration of many senior officers who are still colonels. Naturally these officers expect ‘connected men,’ such as Maruli, to channel their demands to powerful figures like Luhut who also serves as the chairman of Golkar’s advisory board. Paulus—who calls Luhut ‘my commander’ (Tempo.co 2018)—is definitely a key person for active army officers in navigating parliamentary politics. These personal networks in TNI, the government and political parties suggest that the draft law on Pancasila Ideology Orientation has emerged due to their machinations.

However, contrary to the draft presidential regulation on TNI’s counter-terrorist role discussed above, the draft law on Pancasila Ideology Orientation encountered an unexpected obstacle by stoking the anti-communist agenda of Islamic groups. The country’s major Islamic organizations (Nahdlatul Ulama, Muhammadiyah and Majelis Ulama Indonesia) all criticized the draft because it failed to refer to the country’s historic decree made by the nation’s highest decision-making body in 1966 regarding the dissolution of the PKI (Indonesian Communist Party) and the prohibition of Marxist, Leninist and Communist teaching (TAP MPRS No.25/MPRS/1966). For these Islamic groups, this oversight raised the possibility, however remote, of revoking the 1966 decree and reviving communist ideology in Indonesia. Facing this strong opposition from three influential Islamic organizations, the government quickly withdrew its support of the draft law, asking the parliament to take more time to deliberate the content and socialize the law in public dialogue (Kompas.com 2020b).

In this way, the law designed to open the door for active TNI officers to expand their positions in non-military institutions has hit a roadblock. It should be noted, however, that this situation is not due to civil society protests about a revival of militarism, but rather conservative religious pressure on the government to derail military mission creep by invoking the exaggerated specter of a communist revival. Again, the Covid-19 political environment has limited the space for civil society activism and the military is trying to exploit this situation but encountering unexpected obstacles.

|

New Normal

In late May, Jokowi announced his plan to relax the ‘stay-home’ campaign introduced in early April. The lifting of the stay-home order was a concession to the country’s powerful business community which is eager to resume operations (Majalah Tempo 2020a). Despite daily reports of increasing numbers of infections, Jokowi declared that the country should move toward a ‘new normal’ from early June. He asked the public to maintain Covid-19 public health protocols while also lifting restrictions on socio-economic activities. Jokowi’s decision to relax social restrictions drew criticism from health experts and local leaders concerned that he did so before flattening the curve of new infections. What also surprised the public was his mobilization of soldiers (along with the police) to enforce ‘social discipline.’

The TNI commander and police chief soon announced that, following the presidential instruction, they would deploy around 340,000 personnel to four provinces—namely Jakarta, West Java, West Sumatra, and Gorontalo—and 25 regencies/cities that had large numbers of infections to enforce the government’s policy of large-scale social restrictions (PSBB). Human-rights defenders complained that: ‘the public does not need military personnel to remind them to be washing their hands and practice strict social distancing’ (Arshad 2020), and; ‘what we need is a public health approach, not a security approach’ (Kompas.com 2020a).

Jokowi has ignored these criticisms. For him, justifying normalization of business activities and mitigating the economic downturn necessitates a grand gesture of social discipline to convince the public that public health protocols can be maintained while relaxing social restrictions. For Jokowi, deploying the TNI conveys resolute leadership in tackling the pandemic. For the TNI this mobilization expands its mission, providing political cover for ramping up operasi pendisiplinan (disciplinary operations) in many parts of the country, often beyond PSBB areas. The army has broadly interpreted the presidential request to empower its territorial command structure down to the village level, and local commands now mobilize babinsa (village non-commissioned officers) throughout the country for monitoring and patrolling markets, train/bus stations, houses of worship and shopping malls. In the eyes of the police, such military operations are nothing but a serious encroachment on police turf, but for the army, such activities are consistent with its longstanding doctrine of kemanunggalan TNI bersama rakyat (the unity between the military and the people).

TNI’s reactivation of the territorial command structure itself is not to imply that soldiers are mobilized to constrain social activities or control local governance, but rather—perhaps more importantly for the army elites—it provides a very rare opportunity to carve out a new role while conducting a nation-wide territorial mobilization down to the village level in the name of a national emergency response. This is important because it leads to the empowerment of babinsa together with the sanctification of the army doctrine mentioned above, helping the army elites restore the battered legitimacy of the territorial (regional) command structure. It is this territorial command structure that involves around two-thirds of army soldiers that has enabled it to preserve institutional superiority vis-à-vis the navy and the air force.

Post-Suharto era demands for military reform pressured army elites to streamline the territorial commands and relinquish babinsa, because they are associated with the New Order’s authoritarianism (Crouch 2010, 156-7). Within the army there is some support for this reform agenda (Widjojo 2015, 545). Now, with the restoration of babinsa, and carving out a new emergency response role for the territorial commands, the army leadership can fend off pressures to downsize, maneuvering to maintain a bloated army and budget in an archipelagic country where the navy and air force are better suited to dealing with external security threats but starved of resources.

Conclusion

We have seen how the Covid-19 crisis has been instrumentalized by TNI, particularly the army, in a way to advance its institutional agenda. Given the legacy of authoritarianism associated with the army, its expanding role during the current pandemic tends to be interpreted as a comeback of the TNI in politics (Jaffrey 2020; Vatikiotis 2020). This interpretation fits well with the broader discourse about democratic backsliding around the world during the pandemic (Smith and Cheeseman 2020; Croissant 2020).

But, whether the TNI’s role expansion during the Coronavirus emergency signals expanded political ambitions remains in question. It appears that the recent role expansion is primarily motivated by the need to secure positions for senior officers, boost morale and claw back lost ground from the police on security issues rather than re-politicization of the TNI. As we have seen, post-Suharto democratization has contributed to the growth of surplus officers with no positions in the organization, sparking growing frustrations that sap institutional morale. At the same time, during the Jokowi administration, we see the diversification of political patrons who expand their personal networks by promoting the careers of favored officers. Such patrimonial networks have been developed by major patrons such as Luhut Panjaitan, Hendropriyono, and Try Sutrisno since the beginning of the Jokowi presidency, but ‘new comers,’ for example Jokowi’s enemy-turned-ally Prabowo Subianto (ex-son-in-law of Suharto and the current Defense Minister who lost two presidential elections to Jokowi) are also building power networks to elevate connected men from the quagmire of surplus officers.

“We know that frustrated officers have been involved in instigating instability in some cities,” confides Jokowo’s political advisor who believes that job-creation is key to mitigate intra-army frustration. Thus, it appears that these dynamics of intra-army stabilization—rather than institutional political ambitions—are driving the expansion of roles and command structures. Covid-19 has provided useful political cover to advance this agenda.

What does all this mean for Indonesia’s civil-military relations? It was during the Habibie presidency (1998-99) that the TNI enacted major reforms for political disengagement. Security disturbances during the subsequent Wahid and Megawati presidencies sparked a conservative backlash from the TNI that slowed the pace of reforms. President Yudhoyono’s decade in power (2004-14) restored political stability but kept further military reforms on hold (Aspinall, Mietzner and Tomsa 2015). Now, under the Jokowi presidency, the TNI is regaining lost ground on security affairs and has been able to fend off civil society pressure for reform due to the Covid-19 crisis. It seems probable that these developments will shape the new normal in post-pandemic Indonesia, because national lawmakers have no incentive to antagonize the powerful military at a time when it is enjoying public approval for its crisis management role (Indikator 2020, 73). Thus, the army has skillfully exploited the Covid-19 crisis to lockdown and marginalize some key post-Suharto military reforms, demonstrating the virtues of pulling strings behind the scenes rather than direct political intervention. Institutionally, the TNI is reasserting authority while insulating itself from political responsibility.

References

Arshad, Arlina. (2020) ‘Military gets a boost in Indonesia’s ‘new normal’,’ The Straits Times, June 19.

Aspinall, Edward, Marcus Mietzner and Dirk Tomsa. (2015) The Yudhoyono Presidency: Indonesia’s Decade of Stability and Stagnation, Singapore: ISEAS.

Bean, James. (2020) ‘Indonesia’s ‘new normal’ a disaster in the making,’ Asia Times, June 8.

CNN Indonesia. (2020) ‘RUU Ideologi Pancasila, BPIP Bisa Diisi TNI-Polri Aktif,’ June 11.

Croissant, Aurel. (2020) ‘Democracies with Preexisting Conditions and the Coronavirus in the Indo-Pacific,’ The Asia Forum, June 6.

Crouch, Harold. (2010) Political Reform in Indonesia after Soeharto, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Hermawan, Ary. (2020) ‘Politics of pandemics: How online ‘buzzers’ infect Indonesia’s democracy, jeopardize its citizens,’ The Jakarta Post, March 21.

Jaffrey, Sana. (2020) ‘Coronavirus Blunders in Indonesia Turn Crisis into Catastrophe,’ Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 29.

Indikator. (2020) ‘Persepsi Publik Terhadap Penanganan Covid-19, Kinerja Ekonomi dan Implikasi Politiknya: Temuan Survei Nasional, 16-18 Mei 2020,’ June 7.

IPAC. (2016) ‘Update on the Indonesian Military’s Influence,’ IPAC Report No.26, Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, March 11.

Kompas.com. (2020a) ‘YLBHI Minta TNI Tidak Dilibatkan dalam New Normal, Ini Alasannya…,’ June 1.

Kompas.com. (2020b) ‘Tiga Ormas Islam Apresiasi Pemerintah Tunda Pembahasan RUU HIP,’ June 17.

Lane, Max. (2020) ‘The Politics of National and Local Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia,’ Perspective No.46, ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute, May 15.

Laksamana, Evan. (2019) ‘Reshuffling the Deck? Military Corporatism, Promotional Logjams and Post-Authoritarian Civil-Military Relations in Indonesia,’ Journal of Contemporary Asia 49:5, pp.806-836.

Laksamana, Evan and Rage Taufika. (2020) ‘How “militarized” is Indonesia’s Covid-19 management? Preliminary assessment and findings,’ CSIS Commentaries DMRU-075-EN, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Jakarta, May 20.

Mietzner, Marcus. (2020) ‘Populist Anti-Scientism, Religious Polarisation and Institutionalised Corruption: How Indonesia’s Democratic Decline Shaped its COVID-19 Response,’ the Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 39:2.

Majalah Tempo. (2020a) ‘Main Api Normal Baru,’ May 30.

Majalah Tempo. (2020b) ‘Keluar Barak Teroris Dilabrak,’ June 6.

Smith, Jeffrey and Nic Cheeseman. (2020) ‘Authoritarians Are Exploiting the Coronavirus. Democracies Must Not Follow Suit,’ Foreign Policy, April 28.

Sulaiman, Yohanes. (2020) ‘Indonesia’s politicisation of the virus is stopping effective response,’ Southeast Asia Globe, April 10.

Tempo.co. (2018) ‘Sekjen Golkar Lodewijk Paulus: Pak Luhut Komandan Saya,’ January 22.

The Jakarta Post. (2020) ‘Most Indonesians dissatisfied with administration’s Covid-19 response, survey finds,’ May 27.

Vatikiotis, Michael. (2020) ‘Coronavirus challenges Southeast Asia’s fragile democracies,’ Nikkei Asia Review, April 2.

Warburton, Eve. (2020) ‘Indonesia: Polarization, Democratic Distress, and the Coronavirus,’ Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 28.