The Cook Islands and the Pacific Island Nations: Will the Last Person Leaving Please Turn Off the Lights?

Andre Vltchek

From Rarotonga, the Cook Islands. The sea is blue, beaches with golden sand boast palm trees bending almost to the water surface. Beneath barely detectable waves, marine life is fascinating and diverse. On hotel terraces, coconut juices cool the refined throats of jet setters. Traditional huts rub shoulders with some of the most expensive resorts in the world. 500 US dollars would hardly sustain a couple for more than a day here in one of the most expensive parts of the world. Together with neighboring French Polynesia, this has become one of the most expensive parts of the world.

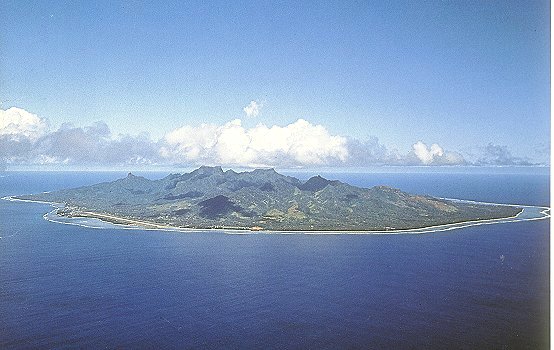

Rarotonga

Rarotonga

Welcome to Rarotonga – the main island of “Cooks”, a country spanning a huge expanse of the Western Pacific, but with a combined land mass of just 236.7 sq kms. “Raro” may be the main island of the country, but its coastal road runs only a bit over 31km.

Muri Beach, Rarotonga

Muri Beach, Rarotonga

The Cook Islands, a former New Zealand colony, is a subdued English-speaking answer to its Francophone neighbor, one of the most lavishly posh places on earth, French Polynesia with its hedonistic icon Bora-Bora.

With all that beauty, one would expect an enormous influx of foreigners searching for sun and sea, and a local demographic explosion to serve them. But the opposite is true: the Cook Islands are losing people at an alarming rate. And despite the arrival of desperate migrant workers from Fiji, the Philippines and elsewhere (almost 300 were given permanent residency status this year), the total number of people living here is declining at alarming rates. According to estimates of the “CIA World Factbook – Cook Islands,” the population fell to 12,271 in 2008. Some older statistics that still circulation claim a total population of the Cook Islands of 18,700, of which 10,000 to 12,000 live in Rarotonga.

Between 1996 and 2007, according to statistics of the Ministry of Education of the Cook Islands, student enrolment in elementary schools decreased by 20% as a result of migration.

There are now 60,000 Cook Islanders living in New Zealand alone. The total population of the Cook Islands is only around 18,700, of which 10-12,000 live in Rarotonga.

Auckland, a promised land for many Cook Islanders

Auckland, a promised land for many Cook Islanders

“I can definitely understand why people are leaving”, explained painter Ani Exham-Dun, who owns a small gallery Art@Air Raro and is a New Zealand-born Cook Islander. “There is nothing they can do here. The other day a girl was caught painting graffiti on the wall in the capital. As a punishment, she was told to scrub graffiti off the wall. That’s what the government did, instead of thinking about how to make life for local young people at least a bit more exciting.”

Boredom is, of course, only one of the problems the Cook Islands have to struggle against. With luxury tourism becoming the main source of income, prices skyrocketed. A small bag of cassava chips at the gas station now costs almost 4 NZ dollars (3.50 US dollars) while a milkshake sells for 7 or even 10. Food, as in the rest of the Pacific islands, is mostly imported from New Zealand or Australia and exorbitantly expensive. But local minimal wages have been stagnating at 5 NZ dollars an hour.

Yet little is being done to encourage local production, while the country falls ever deeper into a dependency trap. “It is evident that the Cook Islands depend on imported food,” explains Vili A. Fuavao, Sub-Regional Representative for the Pacific & FAO. “But very little food is produced there. Cook Islanders are going abroad in search of job opportunities. Meanwhile, some desperate unemployed people from Fiji and elsewhere are trying to migrate to Cooks.”

“The Cook Islands are one of the best performing countries in the Pacific”, explains Elisabeth Wright-Koteka, Director of the Central Policy and Planning Office of the Prime Minister. “Our people want the same standards as New Zealand. But we do not have enough resources to satisfy them. Independence was both blessing and curse. Blessing: because we have our own country and we have freedom of movement, which is guaranteed by the fact that all of us are in possession of New Zealand passports. Without it, we would be just another Tarawa (in Kiribati) – overpopulated, stuffed and desperate. Curse: because now we don’t have enough people and we have to import workers from the Philippines and Fiji and even that is not enough to fill the gap.”

The Cook Islands are not the only country that is losing its most enterprising sons and daughters to richer nations in the area and beyond.

“In the past 40 years the Polynesian island of Niue has experienced a population decline greater than that of any other independent state in the world,” John Conell observed in The Journal of Ethic and Migration Studies in August 2008 of Niue – the country with the smallest population on earth. “More than three-quarters of all Niue-born live overseas, mainly in New Zealand. The balance continues to shift overseas, mainly because of the presence of kin, education and employment opportunities there.”

There are more Samoans and Tongans living abroad than at home. These two countries are sending young people to New Zealand, Australia and elsewhere, in order to support families at home. More than half of the GDP of Tonga is provided by remittances and foreign aid, and Samoa is not far behind. According to “Statistics New Zealand”, in 2006, Samoans were the largest Pacific ethnic group in New Zealand, making up 131,100 or 49 percent of New Zealand’s Pacific population (265,974).” The entire population of (independent) Samoa is around 180,000. Over 50,000 Tongans live in New Zealand and tens of thousands more in Australia and the United States. 112,000 live in Tonga itself.

Even tiny Easter Island, Chilean territory, has more people on the mainland than at home. At the 2002 census, 2,269 Rapanui lived on Easter Island, while 2,378 lived in the mainland of Chile (half of them in the metropolitan area of Santiago).

Needy people from some of the poorest nations in the Pacific – like PNG (Papua New Guinea) and the Solomon Islands – find it difficult to obtain visas. Only relatively well off and educated citizens can secure trips to Australia, New Zealand or the United States, leading to brain drain.

Three Micronesian countries – Palau, RMI (Republic of Marshall Islands) and FSM (Federated States of Micronesia) – have “Compact” agreements with the United States: a deal that brings foreign aid to government coffers, while allowing American military bases to be built on the territory of these nations. Citizens of Palau, FSM and RMI can travel to the US and settle there. They can also send their children to study. Many educated ones never come back. Some of the families from Kwajalein Atoll (where the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site (RTS) is located) that receive rent payments from the US government never spend it in the Marshall Islands.

The 2006 Asian Development Bank Study on Remittances in the Pacific states that “Migration is very significant in Pacific island states, especially in Polynesia, primarily as a response to uneven economic and social development. In many Pacific island countries, the remittances that flow from internal and international migrants to family members at home are increasing in growing importance, especially in Polynesia where they often represent the single most prominent component of national income. They reach levels rarely found elsewhere in the world.”

But in the Cook Islands, claims Elisabeth Wright-Koteka, migration is not necessarily about remittances. “It is different here than in many other island nations. It is not about escape from the culture as in Samoa or Tonga. It is not necessarily about money. We have a culture of migration. We are sailors. Our whole history is about movement. We used to be a colony of New Zealand and we used to send migrant seasonal workers. Migration became part of our culture, of growing up. Young people always like to go away and experience what it is to live in big cities, in the “big smoke”. Some come back. The biggest cohort of returnees is that of people in their 40’s who managed to save money abroad and want to start a new life back in the Cook Islands”.

Secretary of Education of the Cook Islands, John Herrmann would probably agree, but due to migration he is facing urgent problems: “I am struggling to find secondary school teachers”, he explained at a meeting with UNESCO representatives. “Many of our teachers have left the country and we are increasingly relying on overseas teachers, particularly on those from New Zealand.”

In fact, almost the entire country is now relying on foreign workers and professionals. But education is not the only sector suffering from labor shortages – almost entire country is now relying on foreign workers and professionals.

A skilled masseuse in one of the luxury resorts on Muri Beach turns out to be a university-educated economist from Suva, the capital of Fiji. While declining to be identified, she assesses the situation this way: “There are more than 600 Fijians working in the Cook Islands. About one half are employed legally, the other half being overstayers. After the last military coup in Fiji, the situation is extremely bad. Families are breaking apart because they have no means to survive on meager salaries. We are forced to leave. But unlike Cook Islanders, we have only our own (Fijian) passports and now we need visas to go almost anywhere. The Cook Islands are one of the best countries for us to work. There is almost no racism here, unlike elsewhere in Polynesia. People are very welcoming and compassionate. Wages are low for them, but excellent for us. Many Cook Islanders are leaving for Australia or New Zealand and there is always a demand for foreign workers. We are simply filling the gap.”

It is obvious that the problem is becoming increasingly severe. While the Cook Islands as a whole are experiencing depopulation, there is also alarming internal migration which is devastating the outer islands and atolls of the archipelago. The outer islands are hurting more than Rarotonga. Many adults of Aitutaki and Mangaia have left, first to Rarotonga and then to New Zealand. They were simply unable to find jobs on their islands. Many have left elderly people to care for their small children – a situation almost as desperate as on the outer islands and atolls of the much poorer Polynesian country of Tuvalu.

To put it bluntly, there are almost no jobs in Aitutaki and Mangaia. Some time ago the Government of New Zealand severely cut the Cook Islands civil service and reduced or terminated many subsidies that helped support the economy. Unemployment soared and wages plummeted, forcing many to seek employment in New Zealand, predominantly in the shipping industry, where they frequently suffer drug and alcohol addiction. Given the choice, the vast majority of Cook Islanders don’t want to leave New Zealand. Some, however, have been returned by extradition, fighting addiction and criminal records.

Paul Panchyshyn, a visitor from Winnipeg, Canada, was alarmed by what he witnessed in Mangaia, one of the outer islands. “Mangaia is an Island that has seen its population drop by half in the previous decade. There are only about 600 souls left on this unspoiled Pacific gem that was once an exporter of pineapples (reportedly the best in all the South Pacific) and coffee. Cheap exports from Asia and Central America eventually squashed these cash crops and now what few people live on the Island exist solely for the meager tourist dollars. While we were on Mangaia, there were rolling blackouts, actually blackouts of 20 hours a day because diesel was in short supply. We found out later that the one tanker used in the Cook Islands was booked to bring Survivor supplies to Aitutaki and thus Mangaians had to go without fuel and fresh supplies for weeks on end, further diminishing their tourist appeal. Mangaians are wonderful people and fiercely loyal to their Island and the land of their forefathers. Tere, our guide on a cave tour in Mangaia, said the Island had been approached numerous times by big resort pitchmen and every time Mangaians turned them away. I asked why, when the population was dwindling so drastically, they could turn down such major investment. He said it would be an insult to their ancestors, that Mangaians were connected to their land and they would never sell even an inch of their Island to foreign investors. Stubborn, yes. Stupid, no. There are probably few places in the world that have the rugged untouched beauty of Mangaia and it’s so refreshing to hear them insist on keeping it that way.”

It is obvious that the problem is becoming increasingly severe. The Pacific islands are losing people. Environmental refugees are pouring out of Tuvalu, which may be the first country to become uninhabitable due to rising sea level from global warming. Kiribati is facing similar problems, plus overpopulation and social malaise. And the same can be said of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) with some of the worst ecological and demographic problems anywhere in the world (mainly as a result of the US nuclear experiments and present day missile range on Kwajalein Atoll).

Funafulu. Only the very old and the very young remain in Tuvalu

Funafulu. Only the very old and the very young remain in Tuvalu

Social destitution and racial intolerance in the larger Melanesian countries (PNG, Solomon Islands and Fiji) is sending tens of thousands of people to distant shores in search of a better living or simply for survival.

And Polynesia, the eternal paradise once immortalized on the canvases of Gauguin, is not doing much better than the rest of Pacific. Riots in Tonga, child abuse and feudal oppression in Samoa, tremendous efforts (mainly international) to sustain Niue as independent country with only 1.200 inhabitants, gang culture and confusion in French Polynesia.

“I left the Cook Islands and went to New Zealand”, recalls Elisabeth Wright-Koteka. “But I decided to return. I simply like to be here. I like my job, my house. I would like my kids to grow up here. To be a Cook Islander… What is it, really? Maybe a sense of belonging, something we carry inside. It is abstract. We are like a Parrotfish from the long reef – a fish that travels the world but always finds its way home. But coming back doesn’t mean that we stay in one place forever. Maybe our lot is exactly that: a movement between the wide world and the reef.”

As she speaks, a light breeze begins to penetrate the tropical heat. It is suddenly easier to breath. But the water of the Pacific is slowly rising while more and more people are boarding planes with one-way tickets that will take them far away from the palm trees, transparent water and quiet nights of unspeakable Polynesian beauty.

Andre Vltchek – novelist, journalist, filmmaker and playwright. Co-founder of Mainstay Press publishing house for political fiction and LibLit (http://liblit.org). His latest novel – Point of No Return – tells the story of a war correspondent covering New World Order conflicts. A Japan Focus associate, he lives in Asia and the South Pacific and can be reached at [email protected]. He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted at Japan Focus on November 17, 2008. His homepage and blog are available here.

Recommended citation: Andre Vltchek, “The Cook Islands and the Pacific Island Nations: Will the Last Person Leaving Please Turn Off the Lights?” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol. 47-1-08, November 17, 2008.

See other articles by Andre Vltchek on the Pacific Island nations:

Fiji’s Mercenary Military, the US and the Politics of Coup D’état

Samoa: One Nation, Two Failed States

Paradise Lost. Logging and the Environmental and Social Destruction of the Solomon Islands

From the Kwajalein Missile Range to Fiji: The Military, Money and Misery in Paradise

Sinking. Tuvalu and the Pacific Islands in an Age of Global Warming