Abstract: A certain type of historical revisionism involves changing the interpretation of historical material. The resultant commentary or translation, which attributes totally different meanings to the document, can then become a convenient vehicle for historical revisionism. This essay explores how the translator sympathetic to the Kyoto School as also the writer and editor of the reference materials changed the interpretations of the text and other materials related to The Ōshima Memos (approximately 1942–1944/1945). The essay demonstrates how these three agents embellished the authors’ justification of war as resistance and allowed wartime ideology to persist in disguise, dovetailing with historical revisionism.

Keywords: The Kyoto School, the Asia-Pacific War, The Ōshima Memos, translation, historical revisionism

Introduction

The creation of historical narrative is a dynamic process, involving constant dialogue between historical material and historical account, the former being the basis for the latter and the latter clarifying the significance of the former. Iwasaki Minoru and Steffi Richter, scholars from Japan and Germany, where historical revisionism has been growing in power in recent decades, express their concern over the current Japanese situation wherein “the two–way relation between historical material and historical account has been severed” under the influence of post–1990s historical revisionism (Iwasaki and Richter 2008: 534). Iwasaki and Richter deplore the fact that, in the narrative of historical revisionism, there is no such dialogue, but only stories without reference to historical material and without a factual basis. Even when historical fact or material is invoked, it is conveniently altered or arbitrarily interpreted, only to be used as a pretext that the stories are somehow related to fact or material.

However, given that all historical accounts are constructed by certain agents, who view facts and interpret materials from their own perspectives, all historical accounts may be relativized as being just “stories,” leaving no room for conflict or criticism. In fact, historical revisionists often use the diversity of narratives as an excuse to exempt their versions of stories from criticism. They regard criticism as suppression of such diversity. Nevertheless, is it possible to criticize a certain historical account, or affirm one and negate another among several conflicting accounts? If so, what may be the reasons for the same? Although this question might invite diverse responses, Japanese philosopher Takahashi Tetsuya offers a significant suggestion:

When different stories are in opposition or conflict, if we intend to accept one and reject another, naturally, we cannot settle the matter simply by saying “histories are stories.” We need to delve deeper into the concrete content of the story [to be rejected] and illuminate how it exercises the “violence of exclusion and selection” (Takahashi 2001: 48).1

One of the differences between historical accounts and pure fiction is that the former inevitably concern various people who actually lived or are living, and were or are involved in the accounted events, while the latter does not. As such, historical accounts cannot be equated to fictional stories written at the writers’ disposal. Historical accounts, if they seek to be true, or at least truthful, should aim at taking into consideration as many persons as possible, who are involved in the accounted events. Therefore, historical revisionists, who prioritize the honor of the nation–state, select specific, privileged persons, and exclude others, exercise precisely the “violence of exclusion and selection” as Takahashi puts it. This provides grounds to challenge revisionist versions of history, which erase contesting voices and ignore the diversity of people, by using the diversity of historical accounts as an excuse.

This essay will discuss how this “violence of selection and exclusion” is exercised around one set of historical documents called The Ōshima Memos and related to the so-called “Kyoto School” of wartime Japanese philosophers. Among the most prominent members of the school’s second generation were Kōsaka Masaaki, Kōyama Iwao, Suzuki Shigetaka, and Nishitani Keiji, all of whom participated in three roundtable discussions organized by the Chūōkōron journal from 1941 to 1942. Reflecting the era, these roundtable discussions contain abundant statements glorifying Japan’s colonial invasion of other Asian countries under the guise of achieving world peace, in line with Japanese wartime propaganda.

Some scholars, however, including Graham Parkes, Ōhashi Ryōsuke, and Ōshima Yasumasa,2 assert that these documents constitute evidence of the cosmopolitan pacifism of these thinkers and their secret resistance to the wartime regime. One of the aims of this essay is to elucidate how the “violence of selection and exclusion” pervades and transmits itself between the memoranda and these scholars’ accounts.

Yet, this is not the entire story. Drawing heavily on these scholars’ assertions, David Williams translated the Kyoto school’s roundtable discussions into English and published them in 2014 as The Philosophy of Japanese Wartime Resistance.3 Another aim of this essay is to elucidate how discrepancies between the original text and Williams’ translation result in even more “violence of selection and exclusion,” revealing how the memoranda, their accounts, the philosophers’ texts, and their translations, not only respectively but also conjointly, lend themselves to historical revisionism.

In this essay, I will explore how the actions of justifying the war and obscuring its brutality are undertaken by the authors of the original text, the translator, and the editor and writer of the reference material used for the translation. First, I intend to examine those inventions and modifications in Williams’ translation that depict the Kyoto School philosophers as resisting war or the wartime regime, and to observe how his translation embellishes both war and the philosophers’ justification of it. Second, I will argue that The Ōshima Memos, which some authors assert as evidence of the philosophers’ resistance, disprove their assertion, as they contain records of the philosophers’ statements supporting the policy of the wartime regime or proposing more effective mobilization for the war. Third, contrary to claims that the philosophers resisted war by trying to change its ideals, it will be demonstrated that The Ōshima Memos contain records of their statements, which use the idealistic causes of war to disguise imperialism and promote war. Thus, assertions of the philosophers’ justification of war as their resistance to it becomes a repetition of the philosophers’ attribution of varied meanings to the same phenomenon. This entire process ultimately conspires to support colonial violence while denying the existence of the forcefully conquered and massacred masses.

Translation as Transformation: A Comparison between Williams’ Translation and the Original Text

Williams’ translation includes too many baseless inventions and modifications to deal with all of them here.4 Therefore, I will focus only on selected passages that epitomize the problematic nature of this translation. I would especially like to highlight that many of these inventions and modifications were intended to depict the participants according to the translator’s viewpoint. The title of Williams’ book itself, The Philosophy of Japanese Wartime Resistance, reflects the creation of a particular image for these intellectuals through his inventions and modifications.

I will begin with some of the passages allegedly attesting the Kyoto School’s resistance either to the wartime regime or to the Pacific War. What is noteworthy is the insertion of the term “resistance,” which is absent in the original text. For example, in Williams’ translation, the title of the last section of the third roundtable discussion reads, “Concentrating our Powers of Military Resistance” (Ibid.: 363). Alongside the title is the transliteration of the original Japanese phrase “senryoku no shūchū” (Kōsaka et al. 1943: 109). However, the original literally means “the concentration of military powers” and does not imply resistance. The discussion among the four philosophers in this section is about how the entire nation should sacrifice itself and concentrate all its strengths toward the pursuit of the ongoing war. A war waged with all of one’s strength is called “sōryokusen,” which is commonly translated as “total war”; again, it does not imply resistance. Yet, in this last section, Williams translates sōryokusen as “war of total resistance,” “struggles of total resistance,” and “world–historical wars understood as wars of total resistance” (Williams 2014: 364, 365, 367).5 Such recurrent insertion of the term “resistance” into the discussion, which encourages the entire nation and its people to pursue war, raises a question as to what exactly this “resistance” means. At least, it is unlikely that it could mean a resistance to the ongoing war or to the government waging it.

Opinions have been divided about whether the Kyoto School supported and promoted the war or whether it opposed and resisted it. Given that these thinkers’ so-called resistance is not an established fact, much needs to be examined, including the following questions: what does “resistance” mean, what was being resisted, did this “resistance” deserved to be thus called, or did these thinkers really resist, and so on. The written works of these intellectuals and the records of their statements are part of the material based on which such questions are examined and their answers sought. Inserting the term “resistance” into the statements of the intellectuals, based on the assumption that they actually resisted the war, equals forging of evidence. In other words, it amounts to planting what one wants to demonstrate in the material and using it as a means to demonstrate the desired point.

Williams’ translation also consists of other passages wherein his inventions and modifications, despite, or ironically because of their divergence from the original text, highlight and reproduce a certain aspect of the latter. A few examples are found in the final section of the first roundtable. Let me start with how these passages are read in the original text and then move on to how they are changed in Williams’ translation.

One of the participants, Kōyama, argues, “Jihen no shinkō to tomoni genjitsu no igi ga sōzō sarete iru” (“Significance of reality is created as the incident proceeds”) and then adds, “Sensō ni shitemo suikō suru koto ni yotte sono shin no igi ga sōzō sarete kuru” (“In the conduct of a war, it is by pursuing our course of action that we create the war’s genuine meaning) (Kōsaka et al. 1942: 191). To sum up, Kōyama declares that the continuation of war enables the creation of its genuine meaning.

Apart from the evident abnormality of the above statement, understanding its meaning requires bringing its historical background into perspective. “The incident” refers to the Manchurian Incident in 1931 and the China Incident in 1937. These were the Japanese invasions of Manchuria and China. In his 1959 essay “Overcoming Modernity,” Takeuchi Yoshimi, a Japanese scholar of Chinese literature and one of the leading literary critics in early postwar Japan, recalls that, at the time of the China Incident: “It was virtually common knowledge among [Japanese] intellectuals at the time . . . that the state of war called the ‘China Incident’ was in fact a war of invasion against China.” Although many of them felt guilty, once Japan declared war against the United States and Britain, their feelings changed completely (Takeuchi 2005: 122). The Imperial Edict on the declaration of the war qualified China as a protégé of these Western powers and the Pacific War as a fight against their designs to rule East Asia, practically situating this new war as the extension of the two incidents in China (Hirohito 1941). Takeuchi notes the opinions of some Japanese intellectuals of the times, who felt as if “dark clouds” had been “cleared up” by the outbreak of the Pacific War or who wanted to release themselves from the sense of guilt and sought relief in the cause of an allegedly just war (Takeuchi 2005: 119–122). To summarize Takeuchi’s analysis, their feelings changed because once the incidents in China were regarded as the preliminary steps to the new war, the disgraceful wars of invasion were given another meaning and justified retrospectively in the minds of these intellectuals. Kōyama’s statement that the continuation of war enables the creation of its genuine meaning anticipates this exact ideological mechanism, which justifies one war using another, following the policy of the Japanese wartime regime. Clearer formulations of this justification are presented in the four thinkers’ second roundtable discussion.

Next, let us consider how Williams translated Kōyama’s statements at issue. He translated “Jihen no shinkō to tomoni genjitsu no igi ga sōzō sarete iru” (“Significance of reality is created as the incident proceeds”) as “Genuine significance is created as the struggle proceeds” (Williams 2014: 179). Although the preceding sentence in the translation refers to the incidents in question, using the term “struggle” instead of “incident” gives the impression that what matters is not the war itself but the kind of effort involved. Accordingly, in the next sentence in the translation, “Shina jihen” (“the China Incident”) in the original text is replaced with “our struggle in China,” and this struggle is said to have “the creative potential” (Ibid.), yet there is no term meaning “creative” in the original text (Kōsaka et al. 1942: 190). This is not the only place where the translation emphasizes the creativity of war while rewording it as a “struggle.” Williams translates “Sensō ni shitemo suikō suru koto ni yotte sono shin no igi ga sōzō sarete kuru” (“In the conduct of a war, it is by pursuing our course of action that we create the war’s genuine meaning) as “In the conduct of a war, it is by pursuing our course of action that we give genuine meaning to our actions, those things created through struggle” (Williams 2014: 180). The part “those things created through struggle” is the translator’s insertion with no equivalent phrase in the original. This insertion reinforces the aforementioned impression that what matters is not the war itself, but the struggle involved, adding a connotation that this struggle is also a creative effort. Moreover, what is given genuine meaning through continuation is the war in the original text, whereas, in the translation, it is the actions of the people who wage it. This shift of focus from war to action, along with the replacement of “war” or “incident” with “struggle,” obscures the fact that what matters here is war and gives it the appearance of a kind of ethical practice, that of giving meaning to one’s action by pursuing it.

To sum up, the evident abnormality of the original statement regarding the continuation of the war is replaced with another kind of grotesqueness in the translation, which flaunts the allegedly creative and ethical aspects of the colonizer’s aggressive actions. Despite this divergence, there exists a weird affinity between the actions of the authors of the original text and the translator. While the four thinkers of the Kyoto School claimed to give war another meaning, Williams gives it an altogether different meaning. Here, the actions of the authors of the original text are re–enacted by the action of the translator. Both actions are possible only from the standpoint of the colonizer, who ignores the existence of the colonized and silences their voice. For the colonized, the continuation of the war of invasion will never justify initiating war, because there will be more damage, death, suffering and so on, as the war continues. Therefore, the colonizer’s aggressive actions would never be creative or ethical. Williams’ translation not only resuscitates but also embellishes colonial agents, who trample the colonized and establish themselves self–righteously in the original text. Here, the translator is complicit with the authors of the original text to ensure the persistence of colonial violence, making himself an agent of supporting such violence just as the original authors did.

Resistance to What?: Continuities between The Ōshima Memos and the Japanese Wartime Policies

Williams has his own justifications for his inventions and modifications. His reading, or in his own words “fuller rendering of the Japanese original” (Ibid.: 4), is based on his firm belief that the Kyoto School “sought to defy the Tōjō ruling clique and alter the course of the Second World War” (Ibid.: xvii). For Williams, these inventions and modifications aim at giving fuller expression to the texts of the roundtable discussions, which are worthy of being called “the key document of the Japanese wartime resistance to predictable repression at home and doomed expansion abroad” (Ibid.). Williams invokes The Ōshima Memos as the grounds for his argument.

The Ōshima Memos are composed of the written records of secret meetings approximately from 1942 to 1994/1995 between some Japanese navy officers and a group of scholars at Kyoto Imperial University. These scholars were mostly members of the Kyoto School, including Kōsaka, Kōyama, Suzuki and Nishitani. One of the Kyoto School members, Ōshima, acting as the secretary, jotted down notes from the discussions held during these meetings. After his death, Ōshima’s memoranda were stored unnoticed in his house. Ōhashi discovered them in 2000 and published them in 2001, along with his own commentary.6

In his commentary, Ōhashi claims that The Ōshima Memos attest that these secret meetings were “‘antiestablishment’ activities to rectify the military’s policy rather than ‘assisting’ the military government” (Ōhashi 2001: 22). In Ōhashi’s opinion, the wartime Kyoto School philosophers engaged themselves in a “tug-of-war over meaning” as Ueda Shizuteru puts it (Ibid.: 24–25).7 Ōhashi insists that, through their discussions, the philosophers tried to change the meanings of the terminology of wartime propaganda with the goal in mind of “transforming the ideal of the ongoing war, so to speak” and “rectifying the course of the war of invasion” (Ibid.: 22, 24). In cooperation with the navy, which had a long-term rivalry with the army, the philosophers even planned to overthrow the army-led government under the leadership of prime minister Tōjō Hideki, a former army general and minister of war (Ibid.: 14–17). Ōhashi presents The Ōshima Memos as evidence of the Kyoto School’s engagement in such subversive activities. Following Ōhashi, Williams too treats The Ōshima Memos as evidence of the philosophers’ wartime resistance (Williams 2014: 46).

However, upon looking closer, The Ōshima Memos do not back up Ōhashi’s claims. Iwasaki notes that, “Ōhashi merely provides a way of reading [The Ōshima Memos] one–sidedly” (Iwasaki 2002: 120). I discuss a few examples of such one-sidedness below. First, as Ōhashi himself admits and Takeshi Kimoto points out, there is no record in the existing memoranda attesting that the Kyoto School discussed any plan or actions to overthrow the Tōjō cabinet (Ōhashi 2001: 115n41; Kimoto 2009: 100).8 What Ōhashi actually refers to here is a small chart in the retrospective chronological memoranda of past events concerning the war, which appears alongside the term “movement to overthrow the Tōjō cabinet” (Ōhashi 2001: 334–335). However, this is just a part of a record of what happened. Even though one or a few of the participants of the secret meetings might have engaged themselves in such a movement, there is no evidence to attest to this engagement in The Ōshima Memos. Besides, the nature and purpose of this movement also need to be scrutinized.9

Second, although Ōhashi refers to the memoranda of the first meeting on February 12, 1942 as an instance of the philosophers’ “tug-of-war over meaning,” namely, their own way of resisting the wartime regime, what is actually written in the memoranda seems to be different from his assertions. Ōhashi observes that the participants examined whether the term “Greater East Asia Coprosperity Sphere” was appropriate and insists that the Kyoto School took it as a problematic concept (Ibid.: 24). However, just after the title “The Examination of the Term ‘the Coprosperity Sphere,’” it reads:

The words “coexistence and coprosperity,” from which this term is derived, represent the idea that tends to attach too much importance to economic benefits. It lacks morality and has something in common with the worldview of Anglo–Saxon democracy. In addition, speaking of its nuance, this term gives us the sense of easygoingness mainly felt by material prosperity. Therefore, we agreed to avoid using this term (Ibid.: 176).

What the participants problematized about the term “the Coprosperity Sphere” is its lack of morality and emphasis on economic benefits and material prosperity. Emphasizing morality this way does not necessarily mean opposing the policy of the wartime government. In his parliamentary speech on January 21, 1942, about a month before the first secret meeting, Tōjō had stated that the basic principle of the construction of the Coprosperity Sphere was to “establish the order of coexistence and coprosperity based on morality centered on the [Japanese] Empire” (Tōjō 1942: 5–6). Even if it was just his public assertion of the superficial ideal regardless of reality, Tōjō stressed the morality of the Coprosperity Sphere. Problematizing the lack of morality in the concept of the Coprosperity Sphere does not mean problematizing the concept itself. Doing so merely foregrounds the allegedly moral aspect of the Coprosperity Sphere, along the line of Tōjō’s official statement.

Did the philosophers actually conceive other aspects of the Coprosperity Sphere differently enough to counter Tōjō’s policy? This does not seem to be the case. Later, in the first meeting, Suzuki stated: “in East Asia, respective ethnic groups’ cultures and traditions are at very different levels.” To quote Suzuki:

Therefore, putting each and every ethnic group in the right place according to each and every reality is a realistic political measure that should follow naturally. Doing so should be the real basis for the ideal giving guidance to the East Asia Coprosperity Sphere. In this respect, prime minister Tōjō’s statement in parliament about giving independence to one ethnic group but not to another, and the like, has a historical reality (Ōhashi 2001: 181).

The phrase “putting in the right place” (tokoro wo eshimuru) was a part of a popular Japanese wartime slogan, “putting each and every country in the right place” (banpō onoono sono tokoro wo eshimuru). It meant giving each group what it deserves, so that it plays its role in coordination with others in the hierarchical relationship. The general assumption was that this was possible only under Japan’s (or its Emperor’s) leadership. In wartime Japan, this phrase and its variations were frequently used on several occasions and by several people, including in Tōjō’s parliamentary speech (Tōjō 1942: 5). In the context of Suzuki’s statement, “putting in the right place” means considering the developed ethnic group as the leader and treating each of the underdeveloped groups at the levels they deserve. In other words, the underdeveloped ethnic groups need “guidance” from the developed one, as only the developed knows “the right place” for each of the others. Based on this idea of guidance, Suzuki asserts that the developed should grant independence to the underdeveloped and also decide who should be granted independence. In Suzuki’s eyes, without accepting this “guidance” qua domination, there is no independence. Thus, paradoxically, he urges subjugation in exchange for independence.

More importantly, it is striking that Suzuki explicitly appreciates Tōjō’s parliamentary speech in this respect. The phrase “giving independence to one ethnic group but not to another” in Suzuki’s statement refers to the following passage in Tōjō’s speech in January 1942:

In the case that [a certain ethnic group] understands the true intention of the [Japanese] Empire and comes to cooperate with the construction of the Greater East Asia Coprosperity Sphere as its member, the Empire is willing to generously give them the glory of independence. . . In the case that [a certain ethnic group] keeps their stance of fighting back, the Empire is willing to defeat them with no mercy (Ibid.: 7).

Here Tōjō asserts that countries or ethnic groups would be granted independence only if they accepted Japan’s rule and worked for the Coprosperity Sphere. Suzuki simply summarizes Tōjō’s assertion, endorses it, and explains it from the perspective of the developed guiding the underdeveloped. The idea of such guidance was not unique to the Kyoto School. Although expanding this idea may seem to make some difference, it does not problematize the Coprosperity Sphere. Suzuki and Tōjō share the same logic of urging subjugation in exchange for independence, legitimizing other Asian countries’ obedience to Japan, and incorporation into the Coprosperity Sphere constructed by Japan’s invasion. What is crucial is that Suzuki explicitly appreciates Tōjō’s policy in the secret meeting supposedly organized to resist his military regime.

As obvious from the above, some parts of the records of the first meeting show that the philosophers supported Tōjō’s basic policy regarding the Coprosperity Sphere and provided ideas that could undergird it. Thus, what Ōhashi presents as evidence of their resistance to the wartime regime actually contains counterevidence of the same.

Then, is it possible that the philosophers partly supported the policy of the wartime regime and yet tried to stop the war at least? Ōhashi quotes the following passage from Ōshima’s 1965 essay: “The basic theme of the memoranda until the autumn of 1944 was how to end the war advantageously, as soon as possible, while persuading the army reasonably” (Ōshima 2000: 282). Ōshima and Ōhashi may want to say that, even without opposing the war openly, pretending to be cooperative and implicitly dissuading the bellicose army from continuing the war is a form of secret resistance. Ōhashi calls this “antiestablishment within establishment.”

However, The Ōshima Memos include a memorandum, which contradicts the above statement by Ōshima. The memorandum is titled, “Kinds of Consciousness of Losing the War and Countermeasures against It.” Although this memorandum is undated and anonymous, a document with the same title, with slight differences in the type of kana used and the declensional kana ending, is part of The Documents of the Ministry of the Navy (Kaigunshō shiryō), a collection of Japanese navy documents during the prewar and wartime periods. It is the reference material for one of Kōyama’s lectures at the Naval War College on February 21, 1944 (Ōkubo et al. 1997: 322–335). These two documents commonly list, though in slightly different ways and orders, four causes that can create in the Japanese people a consciousness of losing the war. While the reference material in the naval document presents a more in–depth analysis and argument, both documents address these causes in the same vein. Based on this overlap, the memorandum at issue can presumably be dated around February 1944, almost the same period when the reference material for Kōyama’s lecture at the Naval War College was generated.

As its title suggests, the purpose of the memorandum “Kinds of Consciousness of Losing the War and Countermeasures against It” is to propose effective ways to prevent Japanese people from experiencing such feelings by specifying their kinds and causes. It is noteworthy that, this memorandum expresses the apprehension that people’s desire for the war to end soon may make them conscious of losing the war (Ōhashi 2001: 315). Proposing countermeasures against such consciousness and curbing public desire for an early end to the war are possible only by taking the stance that the war should be extended.

In fact, a strong will to continue the war and a firm belief in its righteousness are expressed toward the end of this memorandum:

Every member of the nation should rightfully be aware that “the current war is a dog–eat–dog war that we cannot lose no matter what” and say it out loud…. What is important is the indispensability of clearly explaining why we cannot lose this war, namely, the characteristics and historical necessity of the Greater East Asia War (Ibid.: 319).

To sum up, the claim here is that the ongoing war must be won, hence, it is necessary to explain its significance clearly to the public. The expected consequence is that, by understanding its significance, the public will devote themselves to the war until they win it, without wishing a quick end to the war or thinking of defeat. Here, it is hard to find signs of the will to end the war at the earliest.

Although there is a passage suggestive of criticism of the government in this memorandum, the point at issue is not whether to end the war or not. After suggesting what the government should or should not do, what constitutes its ideal conduct, what faults it should correct and so on, the memorandum states:

It is necessary to convince people of the necessity of the government’s policies, always with a sincere and honest attitude and strong political power, so that they cooperate voluntarily, and to arrange matters such that the government and people form a perfect union to fight against enemies (Ibid.: 316).

The focal point of the criticism is that the government in its current state could not successfully motivate people to cooperate with its policies and effectively mobilize people for the war.10 The policy of carrying on the war is not questioned. In the first place, contrary to Ōshima’s statement, The Ōshima Memos do not contain discussions about ending the war.

“The Tug–of–War over Meaning”: Purpose of Ideals or Purpose of Transformation of Ideals

Given the above, is the philosophers’ attempt at “transforming the ideal of the ongoing war” and “rectifying the course of the war of invasion” discernible in the memoranda, as Ōhashi claims? Does “transforming the ideal” mean more than mobilizing people and continuing the war more effectively? If so, what is it supposed to mean? In the essay Ōhashi draws on, Ōshima writes:

Just as Japan prevented Russia from disturbing Asia in the Russo–Japanese War, Japan has prevented the great powers from dividing China.11 For this very reason, in turn, Japan had to take an ambiguous action, which could not but be seen as imperialistic invasion, just as Europe and the United States did. Then, Japan should show greater morality, display a nonimperialistic stance in its actions, and thus dispel the misunderstandings of the Chinese people. Japan and China will then reconcile, and thus the Greater East Asia War will be terminated. They [the Kyoto School] made such statements in the memoranda. They also strongly implied the same statements in the roundtable discussions (Ōshima 2000: 299–300).

Following initial misleading historical accounts, Ōshima insists that the philosophers in The Ōshima Memos proposed that Japan should rectify its imperialistic behavior, dispel China’s misunderstanding, reconcile with China, and terminate the war. Such proposals may correspond to what Ōhashi describes as the philosophers’ attempt at “transforming the ideal of the ongoing war” and “rectifying the course of the war of invasion.” The question is whether the documents actually read so.

In The Ōshima Memos, some passages seemingly express the philosophers’ regret for the invasion and mention a change in the war ideal. For example, in the records of the second meeting on March 2, 1942, the discussion on the reasons for anti Japanese resistance movements in China contains the following clause: “because Japan’s way of conduct in the past had an imperialistic character” (Ōhashi 2001: 188). Then, another statement follows, suggesting that it would be necessary to “honestly confess and repent (zange suru) the Idea (Idee) of the China Incident (that it was imperialism at first, and while the incident proceeded, its ethicality and historical necessity revealed themselves)” (Ibid.: 188–189). In The Ōshima Memos, these statements are credited to Miyazaki Ichisada, an assistant professor of Chinese history at Kyoto University, Tanabe Hajime, the most prominent disciple of the Kyoto School’s founder Nishida Kitarō, and Kōyama.

Here again, a closer look reveals that something different from Ōshima and Ōhashi’s claim was going on. First, these intellectuals themselves do not change the war ideal but simply state that the war ideal changed itself as the war continued. Second, the intellectuals repent only for the idea that triggered the China Incident and for Japan’s initial conduct; they do not deny the war ideals that are revealed as the incident proceeds, namely, what they call its “ethicality and historical necessity.” After the China Incident, Japan invaded other Asian countries, declared war against the United States and Britain, and announced the construction of the Coprosperity Sphere. The causes held up to pursue these battles were the fight against U.S. and British imperialism and the liberation of Asia from U.S. and British rule. The intellectuals described these causes as the “ethicality and historical necessity” of the incidents.

In The Ōshima Memos, statements asserting that the newly–revealed war ideal justifies the initial invasion appear repeatedly. One of them is found in the record of the eighth meeting on September 19, 1942. The participants are Kōyama, Kōsaka, Kimura Motomori, a professor of pedagogy at Kyoto University, Suzuki, Hidaka Daishirō, the director of student affairs at Kyoto University, Miyazaki, and Ōshima.

Certainly, Japan resorted to stratagem in the China Incident. Besides, a treaty like the Nine–Power Treaty is obviously imperialistic. But, even from now, there is a way to justify the China Incident at the level of thought with the new Idea of the Greater East Asia War (Ibid.: 225).

In short, the claim here is that even imperialistic conduct could be justified by the ideal of the Greater East Asia War, though it was unclear initially and revealed only later.

Surprisingly, even where especially deep remorse for the past invasion is expressed in The Ōshima Memos, the same logic to justify it coexists. Tanabe offers his thoughts during the eleventh meeting on December 9, 1942, whose other participants are Kōsaka, Kōyama, Kimura, Nishitani, Suzuki, Miyazaki, and Ōshima.

Certainly, Japan initiated its action from the standpoint of imperialism at the starting point of the China Incident. But this had a double meaning. It was not merely an imperialistic aspect. This phenomenal aspect, at the same time, was always accompanied by our intelligence and conscience, which had made us already unsympathetic to the manner of proceeding adopted by the [state] leader’s group, right from the beginning of the Manchurian Incident….

The fault that Japan’s action was imperialistic at the starting point should not be ascribed only to the military and a part of the [state] leading group. In the sense that the discomfort felt by our conscience vis–a–vis this imperialism was not strong enough to stop us from being carried away by it, we have a joint responsibility. We need to repent this (Ibid.: 265).

It is undeniable that Tanabe feels deep remorse for his country’s imperialistic invasion in the past. However, what deserves attention is the subsequent turn of his argument.

Since around June this year, national morale has been rapidly slacking off. I wonder if this change has something to do with what I have stated so far. Japan initiated its action from the standpoint of imperialism and yet rationalized this [start] in the middle of the course of events. However, this [rationalization] still works at the level of superficial intelligence and has not proceeded so far as to justify the war during this decade in the depths of the people’s hearts. I wonder if that is why contradictions emerge here and there in reality, and our conscience, unconvinced at the beginning, gains strength later, consequently putting us in the mood to slack off (Ibid.).

Although Tanabe feels pangs of conscience, it is only about the Manchurian Incident and the China Incident, both of which he regards as Japan’s imperialistic invasion. Moreover, he sees such feelings negatively, as a cause of people’s low morale and emotional instability. For him, the pangs of conscience should be driven away, just as low morale and emotional instability should be dealt with. In his opinion, people feel such pangs of conscience, because they have not fully rationalized the past imperialistic invasion and justified the subsequent war wholeheartedly. As a possible solution, he proposes to further extend the rationalization and justification of the war to the extent that public conscience is convinced of the significance of the war and the pangs of conscience are driven away from their minds. Tanabe’s concern centers around how to incline himself and others to engage in the war earnestly so as to continue it.

Commonly discernible in the above passages, based on the records of the three (the second, eighth, and eleventh) meetings, are statements retrospectively justifying war through the ideal revealed by its continuation. Here, the same mechanism is operative as the one in Kōyama’s aforementioned statement in the first roundtable: the continuation of war enables the creation of its genuine meaning. In The Ōshima Memos, the grotesqueness of this mechanism is not as evident as in Kōyama’s statement in the roundtable discussion, partly due to the accompanying expression of remorse over the past imperialistic invasion. Still, it does not change the fact that the mechanism operates despite, or rather just because of this remorse. The way it works recalls Takeuchi’s observation on some Japanese intellectuals who wanted to release themselves from the sense of guilt and sought relief in the cause of an allegedly just war.

In this situation, is it possible to conceive of a reconciliation between Japan and China, as Ōshima asserts the philosophers did? What did they think this reconciliation should be like? In the eleventh meeting in December 1942, Kōsaka states:

The Chungking regime’s attitude of still fighting back uselessly has already stepped out of the realm of rational thinking. They are fighting back only moved by pathos. I have nothing left to say except that they are fighting fueled by antipathy. … Japan still has hope, in that China resists Japan not based on logos but feuded by antipathy, which falls under the category of pathos. That is to say, there should be a way to call for their reflection, by confronting them with the historical fact of East Asia and appealing to their logos (Ibid.: 260).

Kōsaka qualifies Chinese resistance to Japanese occupation as useless, in the conviction that the Greater East Asia War has historical necessity and is hence justifiable. Confident of the rationale of his thinking, he judges Chinese resistance as a mere emotional backlash and ascribes it to the lack of rational thinking and understanding on the part of the Chinese people. Presenting this historical necessity as a “fact” before the Chinese people and rationally persuading them to reflect on the uselessness of their resistance, Ōshima describes it as “dispel[ing] the misunderstandings of the Chinese people” so that “Japan and China will then reconcile.” This means convincing China to accept the ideal of Japan’s war and accept its rule.

It is worth noting that the participants of the three meetings discussed above comprised only philosophers of the Kyoto School and their colleagues at Kyoto University, excluding any navy officer or military personnel. It is unlikely that the philosophers were put under pressure to say something opposite to what they meant.

What is consistently assumed in these statements is that if the war has certain ideals, it can be justified as nonimperialistic. If past imperialistic invasion is thus justified, so would similar acts of aggression in the present and future, even without any change in their imperialistic character. Once this justification was taken for granted, nobody would feel remorse or pangs of conscience for involvement in any war–related action, insofar as it was ideally justified.

In The Ōshima Memos, there is a statement along the above line of thought, professing that Japan cannot be imperialistic and excluding the possibility of problematizing Japanese imperialism. It is a part of the undated memoranda. However, the reference pertaining to the Joint Declaration of the Greater East Asia Conference, published in November 1943, in this statement, suggests that this record is dated around that time.

It is obvious that the cause of this [Greater East Asia] war, the resolution it seeks, and the principle of this resolution, all have a common cause shared by Greater East Asia. This cause is the British and U.S. imperialistic invasion inflicted upon Greater East Asia. Therefore, first of all, it is absolutely impossible for Japan to take an imperialistic standpoint (Ibid.: 307).

Presented above is the sophistry that, because the United States and Britain had previously carried out imperialistic invasions in East Asia, Japan, which began its fight against them, is the opponent of imperialism. Therefore, Japan’s territorial expansion in East Asia cannot be an imperialistic invasion. According to this logic, so long as Japan wages war against the United States and Britain, it can exonerate itself from the blame of imperialism and legitimize its invasion of East Asia. Here, there is no room for reflection about the imperialistic nature of Japan’s conduct. For, even if Japan’s invasion does not stop being an invasion, it is described otherwise and given another look.

The Greater East Asia Conference was held in Tokyo in November 1943, hosting leaders of several members of the Coprosperity Sphere. Its purpose was to give publicity to the Coprosperity Sphere, make a show of Japan’s leadership, and promote unity among the members. The Joint Declaration, published on the last day of the conference, underscored the common cause of the liberation of East Asia from U.S. and British rule as the bond uniting constituent members. What is remarkable is that the declaration stipulated that the members should respect each other’s “sovereignty and independence,” a drastic change from the initial policy that Japan should decide which member is given independence (“Joint Declaration” 1943: 7). However, Ian Nish notes, “For most Asians, the declaration had a hollow ring as a piece of unrealistic propaganda; to believe that Japan would act as their equal partner was impossible” (Nish 2002: 173). Adachi Hiroaki points out that “the ideals upheld [in the declaration] were entirely far from the reality of the Coprosperity Sphere” (Adachi 2015: 159). According to Adachi, “The fact is that [the declaration] was made [for Japan] to overcome [its] disadvantageous position in the war, and that is why it became ‘the reason for continuing the battle more effectively’” (Ibid.). In other words, the ideals were brought up so that East Asian people would stop resisting Japan and join forces with it.

The participants of the secret meetings also had similar intentions and expectations. In a nondated anonymous memorandum, there are passages wherein these intellectuals highly appreciate the Joint Declaration (Ōhashi 2001: 307–308). However, upon reading the subsequent parts wherein the intellectuals discuss the effects of this promotion, it does not seem that they took the ideals of the declaration at face value.

By this means, Manchuria and China’s fear that Japan is imperialistic should be wiped away. If the fear is wiped away, they will cooperate actively. For example, when some people say that Japan exploits Manchuria for resources, they are viewing things from the standpoint of Japan being imperialistic. Based on the Joint Declaration, what is going on should be explained as accommodative cooperation for a common purpose (Ibid.: 308; emphases in the memorandum).

Here, the participants neither propose changing Japan’s imperialistic behavior nor stopping its exploitation of Manchuria’s resources. They just express their expectation that, once the East Asian people embrace the ideals of the declaration, they will not regard Japan’s rule as imperialistic and will accept Japan’s appropriation of their resources. The participants’ focus is not on the content of the ideals respecting each member’s “sovereignty and independence,” but on the function of the ideals in changing the public view of imperialism and exploitation so that people accept these things as they are. The ideals are merely used as tools for persuasion and mobilization.

Thus, passages from The Ōshima Memos, which have been examined above, reveal that the participants of the secret meetings, rather than changing the course of the ongoing war, gave it new meanings to reinforce its idealistic causes. Also, rather than proposing a stop to invasions and exploitation, they proposed changing the perceptions of invasion and exploitation so that colonized people would not recognize them as such. Such actions inevitably justified invasions and promoted the uninterrupted continuation of the war. Yamaguchi Koretoshi’s remark that the Kyoto School “intended to be ‘antiestablishment within establishment,’ but were taken into the party of the opponents and became ‘agitators’ for [Japan’s] invasion in Asia and militarism,” sounds pertinent (Yamaguchi 2020: 95). Consequently, in Yamaguchi’s words, “the Kyoto School ended up playing the role of the surrogate for power conveying to the public the ‘ideology of holy war’” (Ibid.: 93).12

When a specialist writes a commentary stating that certain documents constitute evidence for certain historical actions, a large number of people tend to take this claim at face value without looking into the actual documents. When the English translation or its equivalent is circulated, several individuals do not take the trouble to consult the original text, or often, they do not have access to it. Yet, they assume that the commentary or translation conveys something close to the information or message in the original text. If historical revisionism is a device that “enables one to find in history only that which one wishes to find,” as Iwasaki and Richter (2008: 524) formulate, a commentary or translation giving totally different meanings to the original document can be a convenient vehicle for historical revisionism. For, the commentator and the translator can put anything into their works, to make what they wish to see appear there for the readers.

Ōhashi asserts that, if The Ōshima Memos are translated into foreign languages, the translation will urge some European and U.S. scholars, especially those who draw upon only a small number of English translations of the philosophers’ texts, to change their views about the Kyoto School (Ōhashi 2001: 25–26). Consequently, questions arise as to which translator(s) will translate the memoranda, how, from which standpoint, and based on which principles. Based upon the presupposition that the philosophers resisted the war as Ōhima and Ōhashi describe, will the translator(s) randomly insert the term “resistance” within the translation, even where this term finds no equivalent in the original document? Would such a translation retain only the philosophers’ expressions of remorse or pangs of conscience for the state’s conduct at the beginning of the war and delete their justification of the subsequent war?

Conclusion

Let me summarize the argument so far. The Kyoto School philosophers in the Chūōkōron roundtable discussions asserted that the Pacific War, launched for the cause of fighting U.S. and British rule, retrospectively justified Japan’s invasion of China, in line with Japanese wartime propaganda. The action of thus giving another meaning to the war is repeated by the translator of the text of these discussions. Williams’ translation not only embellishes invasion as a creative struggle but also inserts terms and phrases insinuating the philosophers’ resistance to the wartime regime. In doing so, it gives another meaning not only to war but also to the philosophers’ action of justifying it. The memoranda of their secret meetings, which Williams takes as evidence of this resistance, contain passages retrospectively justifying the war (just like the roundtable discussions) and changing public perceptions of imperialism and exploitation without changing their status quo. Nevertheless, Ōhashi, the editor of the memoranda, and Ōshima, their writer, present the memoranda as attesting to the philosophers’ attempt at resisting the wartime regime and changing its policy of invasion so as to end the war. It was the editor and writer’s action of giving another meaning to war and the original authors’ justification of it that mediated the repetition of the same by the translator. This repetitive action results in the relay of pro colonial violence agency formation from the authors to the writer and editor of the memoranda, and subsequently to the translator of the authors’ roundtable discussions. Throughout this process, colonial violence as well as its justification, are given a new look and disguised as something innocuous.

The perniciousness of such discourse is that, it paves a way for the core tenets of wartime ideology to survive under the guise of resistance to war. Under the pretense of insisting on peace and resistance, this discourse neatly dovetails with historical revisionism, maintaining that the past war was just and necessitated no retrospection. When the core tenets of wartime ideology are propagated under varied guises and gain acceptance as voices from non-Western culture and tradition, criticisms tend to be foreclosed under the pretext of protesting against Western centrism and demanding respect for the cultural other. The logic often used for this foreclosure is similar to that used in wartime Japan, namely, making the fight against Western rule a cause for advocating any action by a non Western country, including its colonial invasion of neighboring countries.

Underlining the importance of opening history to diverse peoples and developing a global perspective, Lynn Hunt states: “The distance we can establish from our own preoccupations fosters a more critical attitude toward group or national glorification and an openness to other peoples and cultures. History has its own ethics” (Hunt 2018: 103). Thus, the ethics of keeping a critical distance from the glorification of a specific, often one’s own, group or nation and from the disregard for others totally contradicts the morality allegedly inherent in the war waged by a certain nation under the banner of certain ideals.

Claims that historical accounts addressing wartime atrocities committed by individuals belonging to a certain nation constitute denigration of the entire nation are invalid. Such claims ignore the existence of victims of atrocities; instead, they victimize perpetrators, expand the group of such new “victims” to include those not involved, and confuse the honor of perpetrators with that of all the people sharing the same nationality. Doing so implies protecting the honor of a specific nation, represented particularly by the honor of a specific category of individuals within it, taking no account of other nations or other kinds of individuals, including the victims of the atrocities in question. To this extent, those claims illustrate the exercise of “violence of exclusion and selection,” in Takahashi’s words.

Certainly, any account of historical events and actions, including that in this essay, is incomplete and destined to be rebutted and rewritten. Tessa Morris-Suzuki writes: “Historical truth is inexhaustible,” and therefore “all we can achieve are…partial representations,” which are “limited” and “contestable” (Morris–Suzuki 2001: 304). To such historical truth, she contrasts “historical truthfulness,” which is “a relationship between the enquiring subject and the object of enquiry.” She continues: “It involves an attempt to be aware of the position from which we approach the past, and of the biases of our own perspective. It requires both critical reflection and a certain breadth of vision” (Ibid.). Given the inexhaustibility of historical truth, historical accounts can always be revised. In the light of historical truthfulness, it is required to examine how, from what standpoint, and based on what ground such a revision would be conducted, as well as what kind of logic and power structure would be operative in such a revision.

In “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life,” Friedrich Nietzsche attributes to humans “the power of employing the past for the purposes of life” (Nietzsche 1997: 64). When some scholars read the Kyoto School’s resistance to the war into their discourse justifying the war, their actions were more or less influenced by the intellectual situation of their times, wherein people generally preferred peace to war and denounced past war and wartime cooperation. Consequently, if the situation changed, such that people forsook peace and moved toward war, would such scholars change their interpretations and praise the philosophers for their active engagement in the past war? Rewriting history by manipulating accounts of the philosophers’ activities and manipulating the meanings of materials, so that the philosophers may be favorably evaluated as per the values in each era, would be nothing but an abuse of history. The irony is that such a rewriting of history would result in continued reproduction of the same old wartime ideology, under varied façades, moving far away from historical truthfulness.

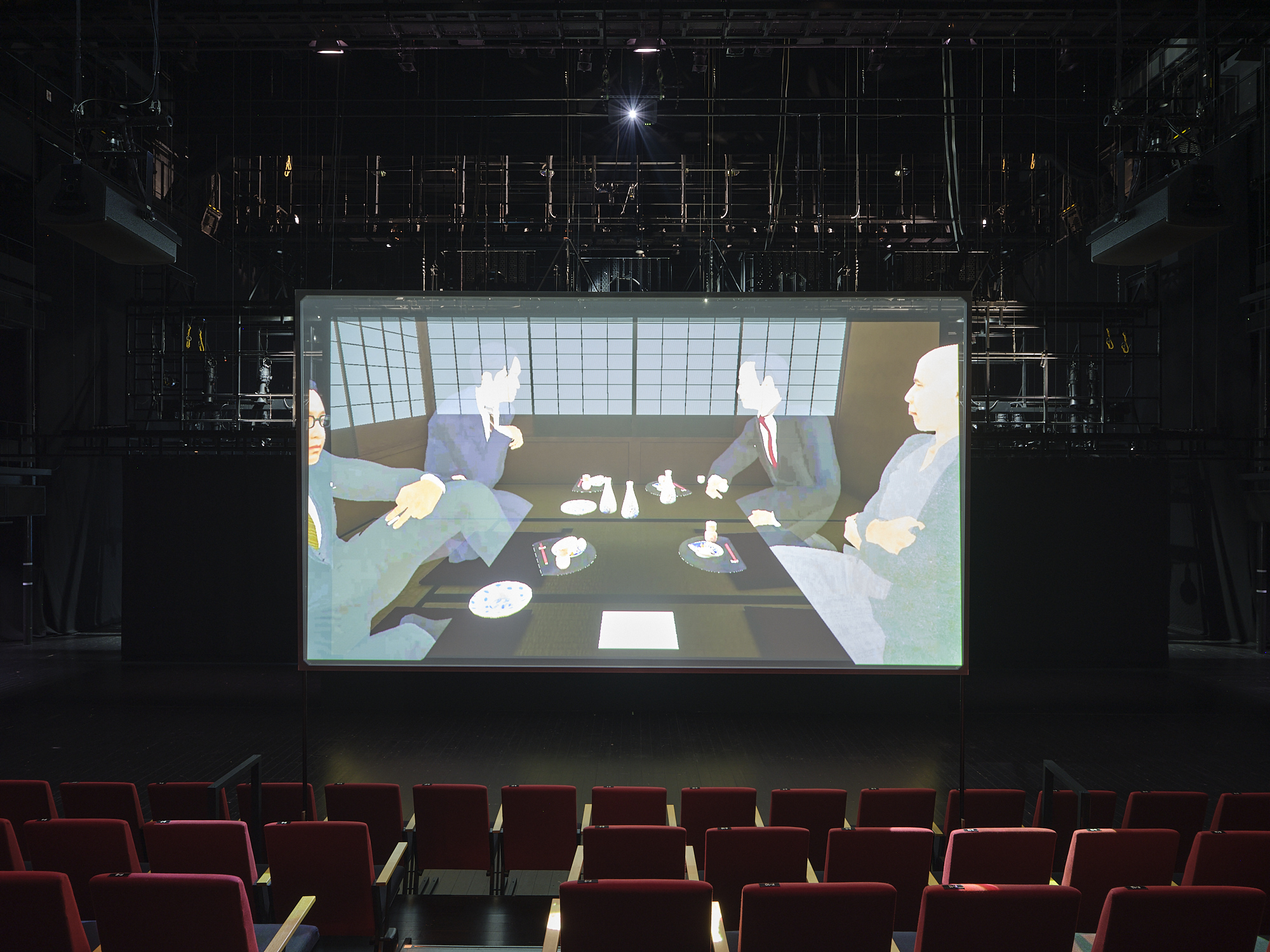

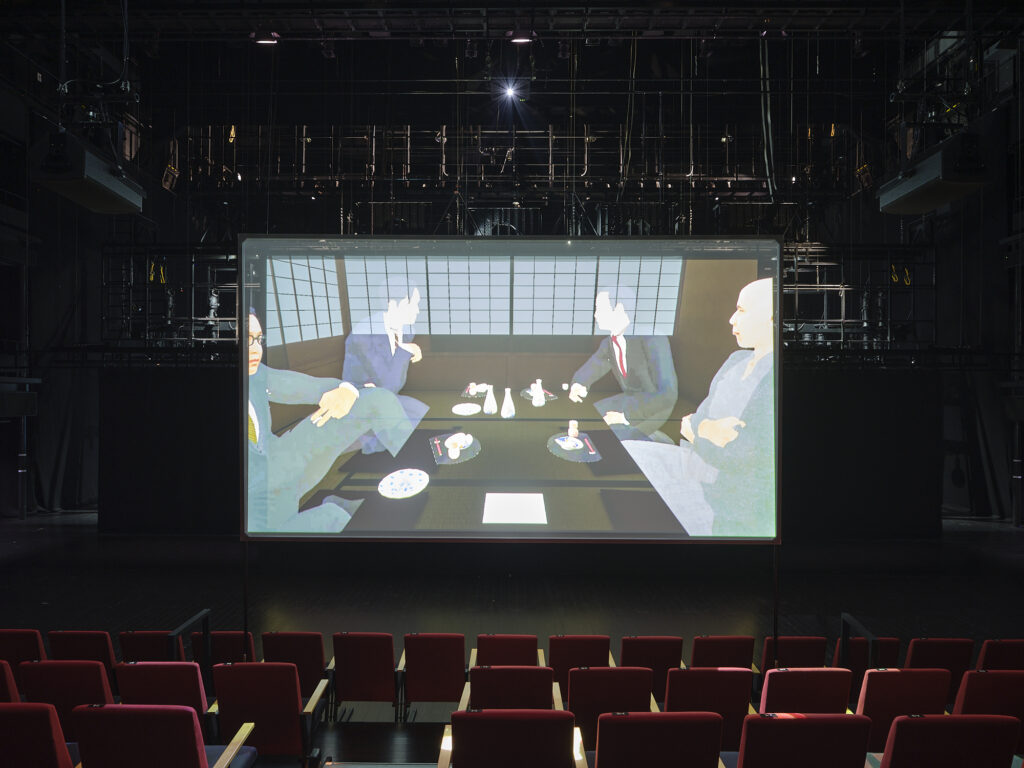

Acknowledgments: The earliest version of this essay was presented at the American Comparative Literature Association in June 2022. I thank Nick Tsung–Che Lu and Anum Aziz for the opportunity to present my paper in their seminar “Ethics of Postcolonial Translation: Exploring New Modes of Power and Resistance in Transcultural Exchanges.” Originally, I drew inspiration for this presentation from my collaboration with Singaporean artist Ho Tzu Nyen and some of his colleagues, namely Arai Tomoyuki, Tsujii Miho, and Yoshizaki Kazuhiko, to make the English script for the installation “Voice of Void” featuring the Kyoto School. I published the ideas I got from this collaboration in a short essay in the catalogue of the installation, Ho Tzu Nyen––Voice of Void: In Collaboration with YCAM, issued by Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media in 2021. I would not have had an opportunity to examine Williams’ translation meticulously, discuss its problems, and plan the above presentation without working with these people. Thus, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude. In this essay, I will mostly use some parts of this script, with slight changes, as an alternative translation regarding the first roundtable discussion. I’m also grateful to Ho Tzu Nyen for generously allowing me to use one of the photos of his installation as the featured image, and to Janfer Chung for helping facilitate the process. Lastly, I would like to thank the reviewers and editors of the APJJF, Tristan Grunow and Mary McCarthy, for taking the time and effort to review the manuscript. Especially, I sincerely appreciate Tristan Grunow, who gave me valuable comments and suggestions, which helped me improve the manuscript.

References

Adachi, Hiroaki安達宏昭. 2015. ‘『大東亜共栄圏』論 [A Treatise on “The Greater East Asia Coprosperity Sphere”].’ 岩波講座日本歴史 [Iwanami Series of Lectures on Japanese History], edited by Ōtsu Tōru大津透, Sakurai Eiji桜井英治, Fujii Jōji藤井譲治, Yoshida Yutaka吉田裕, and Lee Sungsi李成市, vol. 18, 141–176. 東京:岩波書店 [Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten].

‘The Joint Declaration of the Greater East Asia Conference.’ 1943. 6 November. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR) Ref.B13090817500, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/aj/meta/listPhoto?LANG=default&BID=F2013100114432640811&ID=M2013100114432640818&REFCODE=B13090817500.

Hirohito, Emperor Shōwa. 1941. ‘Declaration of the War against the United States and Britain,’ 8 December, translated by The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/sites/default/files/inline-pdfs/T-01415_0.pdf.

Hunt, Lynn. 2018. History: Why It Matters. Cambridge and Medford: Polity.

Itō, Takashi伊藤隆, Uno Shun’ichi宇野俊一, Toriumi Yasushi鳥海靖, and Matsuzawa Tetsunari松沢哲成. 1965. ‘文献から見た『東亜百年戦争』 [“East Asia’s Hundred Years’ War”: From the Perspective of Reference Documents].’ 中央公論[Chūōkōron] 80 (9): 198–211.

Iwasaki, Minoru岩崎稔. 2002. ‘戦争の修辞、世界史の強迫―『世界史の哲学』の喩法について [Rhetoric of War, Obsession with World History: On Figurative Language in “The Philosophy of World History”].’ 総力戦下の知と制度 [Knowledge and Institutions in Total War], edited by Komori Yōichi小森陽一, Sakai Naoki酒井直樹, Shimazono Susumu島薗進, Narita Ryūichi成田龍一, Chino Kaori千野香織, and Yoshimi Shunya吉見俊哉, 111–138. Tokyo: 東京:岩波書店 [Iwanami Shoten].

Iwasaki, Minoru and Steffi Richter. 2008. “The Topology of Post–1990s Historical Revisionism,” translated by Richard F. Calichman. Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 16 (3): 507–538.

Kimoto, Takeshi. 2009. “Antinomies of Total War.” Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 17(1): 97−125.

Kōsaka, Masaaki高坂正顕, Suzuki Shigetaka鈴木成高, Kōyama Iwao高山岩男, and Nishitani Keiji西谷啓治.1942. ‘世界史的立場と日本 [The World–Historical Position and Japan].’ 中央公論[Chūōkōron] 57 (1): 150−192.

Kōsaka, Masaaki高坂正顕, Suzuki Shigetaka鈴木成高, Kōyama Iwao高山岩男, and Nishitani Keiji西谷啓治. 1943. ‘総力戦の哲学 [The Philosophy of Total War].’ 中央公論 [Chūōkōron]58 (1): 54−112.

Morris–Suzuki, Tessa. 2001. ‘Truth, Postmodernism and Historical Revisionism in Japan.’ Inter–Asia Cultural Studies 2 (2): 297–305.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1997. ‘On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life.’ Friedrich Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations, edited by Daniel Breazeale and translated by R. J. Hollingdale, 63–106. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Nish, Ian. 2002. Japanese Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period. Westport: Praeger.

Ōhashi, Ryōsuke大橋良介. 2001. 京都学派と日本海軍―新資料『大島メモ』をめぐって [The Kyoto School and the Japanese Navy: On the Newly Discovered ‘The Ōshima Memos’]. 東京:PHP研究所 [Tokyo: PHP Institute].

Ōkubo, Tatsumasa大久保達正, Nagata Motoya永田元也, Maekawa Kunio前川邦生, and Hyōdō Tōru兵頭徹, (eds.) 1997. 昭和社会経済史資料集成 [The Compilation of Socio–Economic Historical Materials in the Showa Era], vol. 23. 東京:大東文化大学東洋研究所 [Tokyo: Institute for Oriental Studies at Daito Bunka University].

Ōshima, Yasumasa大島康正. 2000. ‘大東亜戦争と京都学派―知識人の政治参加について [The Greater East Asia War and the Kyoto School: On Intellectuals’ Political Engagement].’ 世界史の理論―京都学派の歴史哲学論攷 [Theories of World History: The Kyoto School’s Treatises on Philosophy of History], edited by Mori Tetsurō森哲郎, 274–304. 京都:燈影社 [Kyoto: Tōeisha].

Parkes, Graham. 2008. “The Definite Internationalism of the Kyoto School: Changing Attitudes in the Contemporary Academy.” In Re-Politicizing the Kyoto School as Philosophy, edited by Christopher Goto-Jones, 161-182, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Takahashi, Tetsuya髙橋哲哉. 2001. 歴史/修正主義 [Historical/Revisionism]. 東京:岩波書店 [Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten].

Takeuchi, Yoshimi. 2005. “Overcoming Modernity.” In What Is Modernity?: Writings of Takeuchi Yoshimi, edited and translated by Richard F. Calichman, 103−147. New York: Columbia University Press.

Teshima, Yasunobu手嶋泰伸. 2015. 日本海軍と政治 [The Japanese Navy and Politics]. 東京:講談社 [Tokyo: Kōdansha].

Tōjō, Hideki.東條英機 1942. ‘大東亜建設の構想 [The Plan for the Construction of the Greater East Asia].’ 大東亜戦争に直面してー東條英機首相演説集[In the Face of the Greater East Asia War: Speeches by Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki], edited by Takatori Tadashi高鳥正, 3–11. 東京:改造社 [Tokyo: Kaizōsha]. Digital Collections of National Diet Library, Japan. https://www.dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1459116.

Ueda, Shizuteru. 1995. “Nishida, Nationalism, and the War in Question,” translated by Jan Van Bragt. In Rude Awakenings: Zen, the Kyoto School, and the Question of Nationalism, edited by James W. Heisig and John C. Maraldo, 77−106. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Williams, David. 2014. The Philosophy of Japanese Wartime Resistance: A Reading, with Commentary, of the Complete Texts of the Kyoto School Discussions of “The Standpoint of World History and Japan.” London and New York: Routledge.

- Translations of Japanese texts are mine unless otherwise stated.

- Parkes 2008, Ōhashi 2001, and Ōshima 2000.

- Although Williams calls this text a “reading” of the three roundtable discussions rather than a “translation,” his “reading” was actually circulated as a translation. Further, he treats it as a translation, when he compares it with Richard F. Calichman’s 2008 translation of other roundtable discussions held in 1942 in Japan: “Overcoming Modernity” (Williams 2014: xix). Therefore, I shall be referring to Williams’ “reading” as “translation” in this essay.

- In addition to containing multiple elementary mistakes in Japanese grammar and vocabulary, as well as displaying a lack of basic knowledge about Japanese history and culture, Williams’ translation includes arbitrary inventions and modifications with no basis in the original text, as well as occasional omissions. To cite a few examples, there are frequent mistakes in the transliterations of Japanese terms and the spelling of Japanese names. Several Japanese words, phrases, and sentences were misunderstood and replaced with those having totally different meanings. An ancient Japanese Empress’ name was mistaken for another Empress’ name. A Japanese name referring to an ancient Korean state is consistently misspelled. There are also misunderstandings of German and Latin terms. British biologist Haldane is mistaken for German poet Hölderlin. These are only some of the mistranslations, which are irreducible to the matter of reading or interpretation. Calling this translation a “reading,” as Williams does, would hardly be an excuse. Furthermore, through such random divergences, agency formation takes place between the wartime discourse of the four Japanese thinkers and Williams’ translation, resulting in the endorsement or even the admiration of colonial violence. There are other agents involved in this process of agency formation: Ōhashi Ryōsuke, the editor of The Ōshima Memos, the material Williams drew upon when adding drastic changes to the text in question; and Ōshima Yasumasa, the writer of these memoranda, based on whose testimony Ōhashi wrote his commentary on them.

- The corresponding Japanese terms are found in Kōsaka et al. 1943: 110–111. Williams translates the title of the third roundtable discussion “Sōryokusen no tetsugaku,” literally meaning “The Philosophy of Total War,” as “The Philosophy of World–Historical Wars.” Along this line, he adds the term “world– historical” in the citation. Kimoto Takeshi notes that the Japanese term “sōryokusen” “was originally the translation of the German ‘totaler Krieg’” translated as “total war” (Kimoto 2009: 124). Thus, there is no reason to avoid the term “total war” as a translation of “sōryokusen.” For an explanation of the Kyoto School’s idea of “sōryokusen” and its similarities to and differences from Erich Ludendorff’s idea of “totaler Krieg,” see Ibid.: 103–108.

- For Ōhashi’s overview of The Ōshima Memos, see Ōhashi 2001, 12–14. For Ōhashi’s recollection of the course of things until the discovery of the memoranda, see Ibid.: 338–40.

- These words are found in Ueda 1995: 90.

- Kimoto questions the value of The Ōshima Memos as historical material, because there are many discrepancies between these memoranda and Ōshima’s testimony. Also, Ōshima’s testimony is “a recollection from the postwar perspective” (Kimoto 2009: 100).

- Based on his research on the wartime Japanese navy, Teshima Yasunobu argues that “The navy carried on the movement to overthrow the Tōjō cabinet, because they aimed not at stopping the war immediately but at changing the war situation for better” (Teshima 2015: 187). The purpose of this movement was to continue the war to win it. For an overview of this movement, see Ibid., 185–186.

- This point is more explicit in the reference material for Kōyama’s lecture at the Naval War College (Ōkubo et al. 1997: 326–328).

- Ōshima’s essay was first published in the Chūōkōron journal in August 1965, about one year after Hayashi Fusao’s Affirmation of the Greater East Asia War. Although Ōshima (2000: 299) is negative about this book, he shares with Hayashi the same idea about the outline of Japanese history since the Meiji Restoration: the idea that Japan fought to protect Asia from Western powers. In one of the early criticisms of Hayashi’s book, Itō Takashi, Uno Shun’ichi, Toriumi Yasushi, and Matsuzawa Tetsunari contend that since the Meiji era, Japan had sided with Western powers, pursued its interests in Asia in alignment with them, and subjugated other Asian countries rather than protecting them. With reference to relevant historical events and materials, these historians convincingly argue that the Russo–Japanese War and Japan’s interventions in China, Manchuria, and Korea related to the extension of the above basic Japanese policy. Itō et al. 1965: 202-210.

- For Yamaguchi’s criticism of the Kyoto School’s wartime engagement in reference to Documents of the Ministry of the Navy, see Yamaguchi 2020: 92–96.