Abstract: In September 2022, the curtains at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal in Cambodia opened for the last time. Given the hundreds of millions spent, long delays, few trials, and non-stop controversies, many people wonder if the tribunal was worth the time, money, and effort. This essay describes three perspectives on the tribunals, two negative (purist and progressivist perspectives) and one more positive (the pragmatist perspective). The author then discusses why, despite the tribunal’s shortcomings, he agreed to testify as an expert witness, an experience recounted in his recently published book, Anthropological Witness: Lessons from the Khmer Rouge Tribunal (Cornell University Press, 2022).

Keywords: Cambodia; Khmer Rouge; Genocide; Expert Witness; International Law; Tribunals

Figure 1: Cover of the author’s latest book, Anthropological Witness: Lessons from the Khmer Rouge Tribunal (Cornell University Press, 2022).

Last September, the curtains at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal in Cambodia opened for the last time. Given the US$350 million spent, long delays, two trials, and non-stop controversies, many people have been wondering: was the tribunal worth the effort?

I am one of them. I served as an expert witness at the tribunal in 2016 and recently published a book about the experience, Anthropological Witness: Expert Lessons from the Khmer Rouge Tribunal (Hinton 2022). And I have spent years conducting research on the Khmer Rouge, a group of Marxist revolutionaries who seized power in April 1975 amid the shockwaves of the Vietnam War.

The revolutionaries, headed by Pol Pot, renamed the country Democratic Kampuchea and launched a ‘Super Great Leap Forward’ meant to outdo even Maoist China (Becker 1998; Chandler 1991; Kiernan 2008). Their project of social engineering was a catastrophe. By the time the Khmer Rouge’s Democratic Kampuchea regime was toppled in January 1979, roughly a quarter of Cambodia’s eight million inhabitants had perished. Many died from starvation, overwork, or disease. Perhaps half were executed, their bodies dumped in mass graves the world came to know as ‘the killing fields’ (ECCC 2009).

Due to geopolitics, it took almost 25 years to establish the UN-backed Khmer Rouge Tribunal to seek justice for this genocide. The first roadblock was the Cold War as the government of the new socialist People’s Republic of Kampuchea, which was backed by Vietnam, was allied with the Soviet Union and faced international sanctions. Only after an UN-sponsored election was held in Cambodia in 1993, did the possibility of a tribunal begin to seem possible. It took another decade of bargaining for the United Nations and Cambodia to reach an agreement to hold a tribunal in 2003.

Formally known as the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), this hybrid court includes Cambodian and international staff in most offices. It began operation in 2006 and the first trial was held in 2009, but, in the end, the court convicted only three people and two others died in custody. The last one standing was 91-year-old Khieu Samphan, the former Khmer Rouge Head of State. He appealed his 2018 conviction for genocide and atrocity crimes. After the tribunal’s Supreme Court Chamber denied most of his appeals on 22 September 2022, the court began to shut down.

The ECCC has many supporters and detractors. Most fall into three camps.

Three Perspectives on the Khmer Rouge Tribunal

Figure 2: The ECCC trial chamber. Source: ECCC.

Purists: For legal purists, law has an important but narrow function: ‘to render justice, and nothing else’, as philosopher Hannah Arendt (2006) put it. Arendt made this claim while expressing reservations about Israel’s politicization of the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi bureaucrat who oversaw the deportation of Jews to ghettos and death camps. Doing otherwise, Arendt warned, would lead to victor’s justice and a show trial.

This is exactly what some human rights actors and even ECCC defense lawyers claim happened at the ECCC. Their concerns are legitimate and date back to the complex negotiations between the United Nations and Cambodia over the establishment of the tribunal.

In 1999, a UN-appointed Group of Experts recommended the establishment of an ad hoc international tribunal like the ones held after mass violence in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia (United Nations 1999). However, the Cambodian Government wanted control and only a few trials. The ECCC was established in 2003 as a compromise (Ciorciari and Heindel 2014; Etcheson 2020).

The structure of this hybrid court, mixing UN and Cambodian personnel in most offices, raised concerns about political interference that proved prescient. Corruption allegations almost immediately emerged. They were followed by evidence of the Cambodian Government’s political interference in the trials, including its minimization of the number of suspects tried.

As a result of such controversies, most legal purists regard the tribunal as a failure.

Progressivists: Progressivists acknowledge such legal shortcomings but believe courts like the ECCC have a broader purpose than legal procedure. Justice, in their view, can be curative and even transform a society. From this ‘transitional justice’ perspective, international tribunals can help achieve the liberal progressive goal of turning post-authoritarian countries into democracies governed by the rule of law and human rights.

As I have detailed elsewhere (Hinton 2016 and 2018), the ECCC was deeply intertwined with the idea of transitional justice. The 2003 UN–Cambodia agreement claimed the tribunal would help Cambodia’s ‘pursuit of justice and national reconciliation, stability, peace and security.’ These transitional justice goals were embodied by the court’s slogan, ‘Moving Forward through Justice’. Transitional justice actors like the International Center for Transitional Justice and Open Society Justice Initiative sought to help facilitate Cambodia’s transformation.

The hoped-for democratic transformation did not materialize. Instead, during the course of the tribunal proceedings, Cambodia’s ruling party cracked down on the opposition, suppressed human rights, drew close to China, and increased political surveillance. Some claim that, by the end of the tribunal, Cambodia had turned into an authoritarian state (Bennett 2021; Morgenbesser 2019).

Given this outcome, most progressivists also regard the ECCC as a failure.

Pragmatists: Like purists, pragmatists view the possibilities of international justice as limited. But they regard all tribunals, from the post-Nazi Nuremberg trials to the International Criminal Court, as political. And like progressivists, pragmatists believe that the impact of international justice extends beyond the courtroom—even as they are skeptical of the claim that international justice is transformative.

Instead, pragmatists look for modest achievements that can help a post-conflict society attain a measure of justice and healing for atrocity crimes. Along these lines, the ECCC’s accomplishments included holding some Khmer Rouge leaders accountable, combatting long-standing Khmer Rouge genocide denial, and deterring would-be genocidaires. And, though limited in purview, the tribunal clarified the historical record and compiled key documentation about Khmer Rouge rule.

Working with non-governmental organizations, the court also robustly engaged victims and the broader public. A 2018 study found that, despite outreach challenges in a rural country, most Cambodian victims view the ECCC favorably and are content with the small number of trials (Williams et al. 2018; see also Chy 2009).

These achievements are not transformative. But they are significant. For this reason, most pragmatists view the tribunal as a success.

An Anthropological Witness Perspective

Where do I place myself among these three camps? And why, given the shortcomings of the court, did I agree to testify?

It was not an easy decision, as I recount in Anthropological Witness. The book begins:

Tuesday, September 22, 2015 (Newark, New Jersey, USA)

As I sit at my desk, finishing a book manuscript on an international criminal tribunal being held in Cambodia, I receive a surprise e-mail from that very court. The message confronts me with a dilemma. It also raises questions about my role as an anthropologist and my responsibility to bring scholarly insights into the public sphere.

“I would like to inform you that your name has been put before the Trial Chamber of the ECCC on a confidential and provisional Expert Witness list,” reads the message from an official at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) …

“The Trial Chamber has requested that I make contact with you,” the message continues, “to determine your willingness and availability to travel to Phnom Penh, Cambodia to testify before them an Expert Witness” in the trial of the Case 002 defendants, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan …

Many scholars would leap at the chance to be a part of [their] trial at the ECCC, one of the most significant international criminal trials since the Nuremberg Tribunal’s prosecution of Nazi leaders. My initial response is ambivalence and apprehension. I have reservations – and questions. (Hinton 2022: 1–2)

I was hesitant for several reasons. The first and most predictable one dovetailed with concerns expressed by purists and progressivists: wariness of Cambodian political influence. Indeed, I was in the midst of writing a book, The Justice Facade: Trials of Transition in Cambodia, which discussed these controversies in detail (Hinton 2018). Second, there was a professional risk since the research and testimony of expert witnesses often comes under attack. This concern has led some scholars to decline serving as expert witnesses.

A few have refused a summons out of fear that the epistemology and practice of law are too at odds with that of the humanities and social sciences (Wilson 2011; see also Eltringham 2019)—perhaps most famously the French historian Henry Rousso (2002), who turned down a request to testify at a Holocaust-related trial. This was perhaps my greatest concern as well, particularly given that my earlier work on the tribunal had examined at length the ways in which victim testimony is ‘clipped and pruned’ to fit into legal definitions of criminality supporting a judgement of guilt or innocence (Hinton 2016 and 2018).

Such challenges notwithstanding, I decided that the pros of testifying outweighed the cons. On the one hand, as someone committed to public scholarship, I felt a responsibility to make a small contribution to the process of justice and accountability for the Cambodian genocide. On the other, I felt an obligation to the many Cambodians I had interviewed or met over the years, especially the survivors who had told me about their experiences during Democratic Kampuchea.

And so, my decision made, I testified for three and a half days in March 2016. Anthropological Witness draws on creative non-fiction literary strategies (narrative structure, dialogue, first-person voice, character, setting, and so forth) to tell the story of how I navigated the challenges of providing expert witness testimony as I sought to offer explanation in a court of international law.

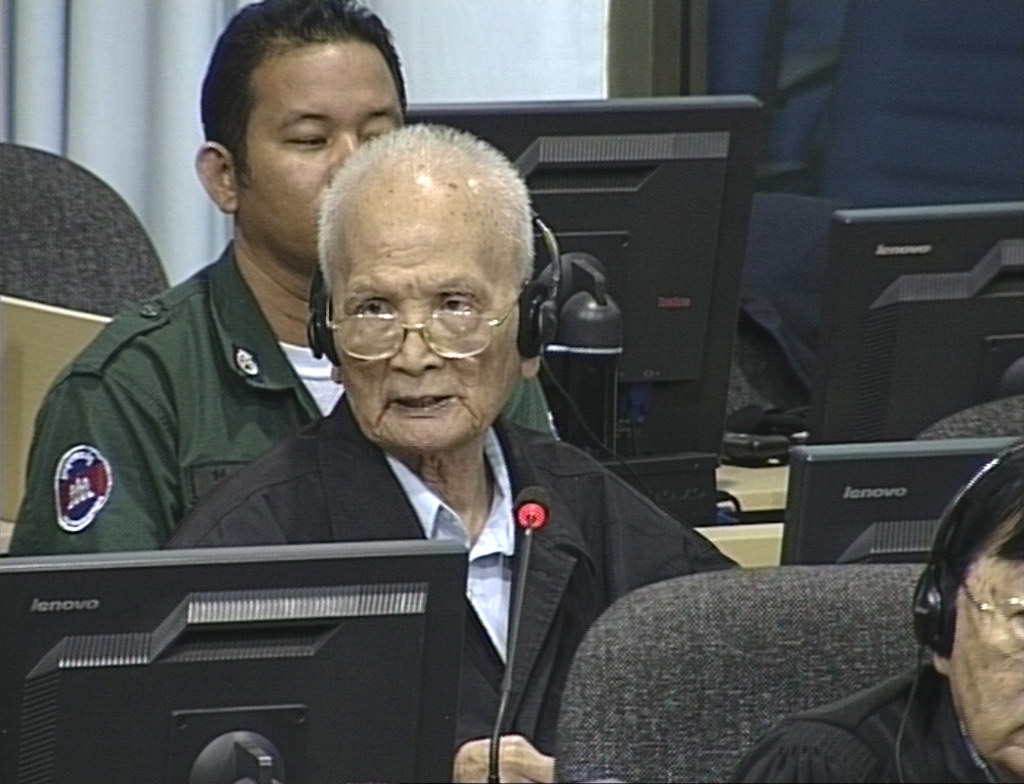

My testimony—and the book—culminates in an account of my courtroom exchange with Pol Pot’s deputy and ‘Brother Number Two’ Nuon Chea, who, upset with my testimony, broke his long-standing silence at the court to try to rebuke my testimony. He also posed two questions to me that sought to displace responsibility for the genocide onto the United States and Vietnam. In real time, I had to respond to genocide denial.

Figure 3: The author testifies at the ECCC in March 2016. Source: ECCC.

Figure 4: Nuon Chea, ‘Brother Number Two’ speaks at the ECCC. Source: ECCC.

The ECCC prosecutor, Bill Smith, later wrote: ‘Sitting at the prosecution bench as this exchange was unfolding. I watched Dr. Hinton ably and respectfully respond to Nuon Chea’s view’ (Smith 2018: 38). Smith then added: ‘I thought to myself, would Alex Hinton ever have thought that, when he was a 31-year-old PhD research student sitting in a village in Kampong Cham province in the middle of Cambodia collecting evidence on the genocide of the Khmer Rouge, that 25 years later he would be discussing his findings [directly] with Nuon Chea in a trial where Nuon Chea was charged with genocide?’

‘All Dr. Hinton’s prior hard work had paid off,’ Smith finished, ‘and he was able to make his contribution to the accountability and reconciliation process in Cambodia in one of the most salient possible ways’ (Smith 2018: 38). Smith was right—I could never have imagined it.

As should be evident by now, I would place myself in the pragmatist camp, if I had to choose. While recognizing the limitations of the ECCC and politicization of international tribunals in general, I recognize that such courts can still accomplish a great deal of good. The ECCC, as the journalist Elizabeth Becker (2022) underscored in a review of Anthropological Witness, ‘gave Cambodia a taste of justice.’

It was for such reasons that I agreed to testify at the ECCC. I wanted to contribute to the process of justice-seeking in Cambodia by helping explain how and why genocide takes place. Despite their limitations, tribunals can open spaces for such understanding about the past.

In this regard, the ECCC offers us a lesson learned and a remainder. Justice is a salve. While it is messy, it can soothe and help heal. But if you expect it to cure, justice will break your heart.

This essay is partly adapted from an earlier article by the author, ‘Justice at Last for Cambodia’s Killing Fields?’, which appeared in The Diplomat on 21 September 2022.

References

Arendt, Hannah. 2006. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York, NY: Penguin.

Becker, Elizabeth. 2022. ‘In the Hot Seat.’ Mekong Review, Issue 29, November.

Becker, Elizabeth. 1999. When the War Was Over: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge Revolution. New York, NY: PublicAffairs.

Bennett, Caroline. 2021. ‘Cambodia 2018–2021: From Democracy to Autocracy.’ Asia Maior, Issue XXXII.

Chandler, David P. 1991. The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War and Revolution since 1945. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Ciorciari, John D. and Anne Heindel (eds.). 2014. Hybrid Justice: The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Chy, Terith. 2009. A Thousand Voices. Phnom Penh: Documentation Center of Cambodia.

Eltringham, Nigel. 2019. Genocide Never Sleeps: Living Law at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Etcheson, Craig. 2020. Extraordinary Justice: Law, Politics, and the Khmer Rouge Tribunals. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). 2009. ‘Demographic Expert Report.’ ECCC website, 30 September.

Hinton, Alex. 2022. ‘Justice at Last for Cambodia’s Killing Fields?’ The Diplomat, 21 September.

Hinton, Alexander Laban. 2022. Anthropological Witness: Lessons from the Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Hinton, Alexander Laban. 2018. The Justice Facade: Trials of Transition in Cambodia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hinton, Alexander Laban. 2016. Man or Monster? The Trial of a Khmer Rouge Torturer. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Kiernan, Ben. 2008. The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Morgenbesser, Lee. 2019. ‘Cambodia’s Transition to Hegemonic Authoritarianism.’ Journal of Democracy 30(1): 158–71.

Rousso, Henry. 2002. The Haunting Past: History, Memory, and Justice in Contemporary France. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Smith, William. 2018. ‘Justice for Genocide in Cambodia: The Case for the Prosecution.’ Genocide Studies and Prevention 12(3): 20–39.

United Nations. 1999. ‘Report of the Group of Experts for Cambodia Established Pursuant to General Assembly Resolution 52/135.’ U.N. General Assembly Security Council, 53rd session, UN Doc. A/53/850, 8 February.

Williams, Timothy, Julie Bernath, Boravin Tann, and Somaly Kum. 2019. Justice and Reconciliation for Victims of the Khmer Rouge? Swiss Peace website, November.

Wilson, Richard Ashbury. 2011. Writing History in International Criminal Trials. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.