The Kaminoseki Nuclear Power Plant: Community Conflicts and the Future of Japan’s Rural Periphery

Tomomi Yamaguchi

Summary

The article explores the controversy surrounding the construction of the Kaminoseki nuclear power plant in Yamaguchi prefecture. While briefly introducing opposition activism against the plant, I introduce the voices of proponents of the plant. By doing so, I highlight the harsh economic realities facing this and other rural communities and divisions within the construction site community.

Keywords

Kaminoseki, Fukushima, nuclear power plant, nuclear energy, energy policy, urban/rural divide, coucntryside, Chugoku Electric Power, Politics, Community divisions

The Atomic Age and Ashes to Honey

In the midst of the catastrophe of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant that began on March 11, a long-planned symposium, “The Atomic Age: From Hiroshima to the Present” was held on May 21 at the University of Chicago. 1 An important goal of the event from its earliest planning stages was to highlight the connection between atomic weapons and atomic energy by showing two films on the theme, to be followed by panel discussions. The catastrophe at Fukushima and throughout Japan’s Northeast has had an extraordinary impact on life in the immediate vicinity and caused major disruptions and danger to people and the natural environment far beyond. Among the consequences of the multiple earthquakes, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown have been a rethinking of Japan’s nuclear power agenda and the future of the nation’s energy policies. The Fukushima disaster has highlighted the culture of secrecy surrounding nuclear weapons and nuclear energy that has long crippled public discussion of the issues, and raised questions about rural/urban power differentials, which have been amplified by the catastrophe. The process used to determine where nuclear plants are built is of particular concern and has caused significant community divisions.

One of the films featured at the symposium was Kamanaka Hitomi’s Ashes to Honey: Toward a Sustainable Future (link)2, which is the third of a trilogy by this director that deals with nuclear issues (the others are Hibakusha at the End of the World (2004) and Rokkasho Rhapsody (2006)). The film explores the ongoing movement by the residents of Iwaishima, a small, Inland Sea island in Yamaguchi Prefecture, opposing the construction of the Kaminoseki nuclear power plant, which is separated from the construction site by just 3.5 km of ocean.3

|

Iwaishima seen from Tanoura, the construction site of Kaminoseki Nuclear Power Plant. Source. |

Kamanaka has been especially busy since March 11, traveling throughout Japan for screenings of her films, mostly organized by local citizens’ groups. She has also addressed numerous gatherings and symposiums, and has been interviewed in the mass media. Ashes to Honey, along with her two previous films, now gets the type of attention that she could never have imagined before the Fukushima Daiichi accident. Kamanaka has said that her aim in producing the films was to make the public aware of the dangers of radiation – whether from the use of weapons or from nuclear power plants – because she did not want anyone to be affected by radiation ever again. Now, sadly, Kamanaka’s films are gaining attention due to the very catastrophe that she had hoped to avert through spreading her message; nevertheless, the films have been functioning as extremely powerful tools for raising awareness and encouraging people to engage in actions against nuclear energy.

|

Ashes to Honey poster (center) on a bulletin board in Iwaishima, along with a poster for a signature drive against the plant’s construction (photo by the author). |

Ashes to Honey is one of two films on the Kaminoseki plant controversy released in 2010, along with Houri no Shima (Sacred Island) by Hanabusa Aya.

The two films, both the work of independent women filmmakers, focus on the residents of Iwaishima, the vast majority of whom have been opposing the construction of the plant for the past 30 years out of fear for their livelihood and the natural environment surrounding the island. The fact that supporters of the Kaminoseki plant feature in neither film is indicative of the polarized interpersonal relations in the community, and the difficulties for opponents of the plant to even approach supporters to hear their side of the story.4 In this article, I will explore the “other side” of the Kaminoseki debate, i.e., the perspective of those who support construction. My own position is opposition to the construction of the Kaminoseki plant, and opposition to nuclear energy as well. Nevertheless, I have attempted to hear the views of the supporters. This turned out to be quite difficult. Because the films of Iwaishima – and many other media reports as well – do not feature the supporters’ side, opponents of nuclear power plants tend to see the conflict as one of old and poor Iwaishima residents versus powerful and greedy corporate superpowers such as Chugoku Electric, together with the local and national governments. While these battle lines do exist, the story is not so simple. An adequate account would need to reflect the reality of struggling rural communities facing population decline and loss of livelihood, the package provided to secure support of local communities, and complex human relationships in once tightly knit communities. By exploring the story of “the other side,” I, as an opponent of nuclear energy, am better able to see the problems associated with the claims and activist strategies of the opposition, most particularly, the question of the nature of their commitment to the situation of so-called “ricchi” (plant sites) communities, all of which are struggling rural communities.

30 Years of Struggle Over the Construction of the Kaminoseki Plant

In June 2010, I visited Iwaishima Island with a friend, Yuki Miyamoto of DePaul University, who was also one of the organizers of the Atomic Age symposium. We wanted to see for ourselves the site of the protest movement against the Kaminoseki plant. Our visit was only for a few hours, yet we saw numerous indicators throughout the island of protests – in the form of signs, posters, and flyers.

|

Anti-nuclear Power Plant Sign in Iwaishima (photo by the author) |

Wandering around the tiny island, Yuki and I went into the small structure that was the Iwaishima branch of Kaminoseki town hall. We asked the person at the reception desk for a map, and inquired about what there was to see on the island. He smiled, gave us a map, and kindly started to explain various sightseeing spots. I then noticed a flyer at the reception window that read: “Study tour to visit the Genkai Nuclear Power Plant in Saga.” The flyer said a tour for 30 residents had been organized by the Kaminoseki Town Hall, with the town paying transportation and lodging costs for tour participants. I asked the man at the reception desk about it, and there was an awkward moment of silence and tension; it was obvious from his discomfort that he preferred to avoid such conversations with outsiders. Yet, as a municipal employee of the town of Kaminoseki, he has to promote the plant’s construction, even while working in Iwaishima. This memorable moment encapsulated the level of divisiveness of this issue on this small island, and in the town of Kaminoseki. The municipal government of Kaminoseki is promoting the plant’s construction while Iwaishima Island’s residents overwhelmingly oppose it.

There is an almost 30-year history of intense conflict between supporters and opponents of the Kaminoseki plant construction, dating back to 1982. The town of Kaminoseki comprises a peninsula and several islands, including Iwaishima. The majority of the 3,300 residents of the town support the construction, along with seven organizations in the town and the Kaminoseki Town government under the three mayors it has had since 1983. On the other hand, 90% of the 500 residents of Iwaishima Island oppose the construction. According to Iwaishima residents, many of whom have been engaged their whole lives in fishing and small-scale farming, their motive in opposing the plant is to maintain their livelihood as well as to preserve the diverse and vibrant natural environment of Iwaishima and the Inland Sea. Both Ashes to Honey and Houri no Shima describe the everyday realities of the aging residents, in an island struggling with youths leaving to find jobs and overall population decline. The residents’ lives are closely entwined with their protest movement against the plant. One such example is the weekly demonstration held in Iwaishima every Monday for the past 30 years.

|

1,100th Monday demonstration in Iwaishima in June 2011 |

There have been numerous court cases, signature drives, rallies, demonstrations, gatherings and protests among those against construction over three decades. There are also activists coming from outside of the town – such as the “Rainbow Kayaking Team” – which aims to “maintain the wonderful nature of the particularly beautiful bay of Tanoura, for future generations”5 and has been blocking construction of the Kaminoseki plant by Chugoku Electric Power, by using their kayaks, alongside Iwaishima residents doing the same with their fishing boats. Over the years the construction site has been a locale of intense conflict between Chugoku Electric Power and the Iwaishima residents and their supporters. In this situation, Chugoku Electric Power had great difficulty starting construction, and when it finally began in 2010, the company faced intense protest from the islanders and the Kayaking team.

|

Protest against Chugoku Electric by the islanders |

On February 21, 2011 construction to fill in Tanoura Bay for the plant finally restarted. But on March 11, the Tohoku Earthquake occurred, resulting in the massive accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. On March 15, Chugoku Electric halted work on the Kaminoseki plant after the governor of Yamaguchi Prefecture, Nii Sekinari, asked the company to stop construction. Construction has not resumed since then, although Chugoku Electric Company still maintains its stance to proceed with the project.

“The Other Side” of the Kaminoseki Debate

I became interested in the Kaminoseki issue during five years of research on anti-feminist movements in Japan. In the course of research, a small local paper, Nihon Jiji Hyōron (Japan Current Review; hereafter Jiji Hyōron), based in Yamaguchi City, caught my attention for its extensive critique of feminism. This local newspaper, usually about eight pages long, is published every two weeks. The paper’s official subscription is 30,000, and despite its focus on local content, Jiji Hyōron is distributed widely throughout Japan, especially to conservative politicians. When I started my interviews with employees of the paper – primarily its editor-in-chief, Yamaguchi Toshiaki – I was diverted from the issues I had assumed were primary to them, as I came to realize that they considered the construction of the Kaminoseki plant to be the top priority, along with keeping the U.S. base in Iwakuni. Indeed, Yamaguchi’s “life’s work” is to promote construction of the Kaminoseki plant, which he firmly believes “will benefit the local community, and the prefecture of Yamaguchi where I grew up, where I continue to reside, and which I love deeply,” and “also meets Japan’s national interests.” He has been covering issues related to the Kaminoseki construction and nuclear energy for the past 30 years, ever since he began his career as a journalist, and he has also been an activist on the issue. During repeated visits to Yamaguchi prefecture, I tried to listen to his stories.

Virtually every issue of this small newspaper contains articles in support of nuclear energy and the construction of the plant. This support has continued in the wake of Fukushima. As with other supporters of nuclear power, Jiji Hyōron points out its advantages as a means to control global warming and energy security, along with its economic benefits for the local economy. Japan is without natural resources that can provide a constant, reliable energy source, and its self-sufficiency rate for energy is only 4%. The paper argues that “this fact, combined with environmental concerns – such as global warming – makes nuclear power plants necessary.” Like many nuclear energy proponents, Jiji Hyōron also is extremely positive about technology – they have devoted major coverage to the “dream” plan (which has not been working) of the fast breeder reactor Monju, and the development of nuclear fusion reactors. The production of high-level radioactive waste is considered to be necessary and the paper describes how NUMO (Nuclear Waste Management Organization of Japan), the government-approved body whose task is to determine final disposal of high-level radioactive waste, has been looking for landfill sites since 2002.6 The safety of nuclear power plants and the superiority of nuclear technology in Japan, despite frequent earthquakes, were stressed repeatedly in the pre-3/11 coverage of the paper.

An argument that particularly stands out is the claim that “the plant is the means to finally start building a real community for Kaminoseki residents”: the town’s population has decreased by half in the past thirty years (in 1980, there were 6,773 residents, and there were 3,332 residents in 2010.) The percentage of elderly over 64 years old is 49.4%, the highest in the prefecture, and the average age of residents is 74. The demographic shift to the cities and abandonment of rural areas is a serious issue in this town, as in most rural areas throughout Japan.

An interview with Kaminoseki Mayor Kashiwabara Shigemi in the January 2009 issue of Jiji Hyōron highlights the controversy. Explaining how divided the town has been over the nuclear power plant, he goes on to express his deep appreciation for the grant-in-aid worth 2.5 billion yen ($30 million) from the national government, as well as money from the Chugoku Electric Power Co. This financial support has enabled the town to deal with a serious fiscal crisis. With the construction of a new plant, the mayor believes it will finally be possible to develop the community. To build a “flowering ocean town” (hana saku umi no machi) is his goal, “with cable TV in all homes, buses for the elderly and disabled, publicly-operated resort centers (hoyōjo), a new municipal building,” and so on. He would like to have more tourists, and to buy the many empty houses in the town and replace them with public housing. He states “I want to bring back vitality, promote local food, and empower the local economy by using the power plant.” (Jiji Hyōron, Jan 19, 2009)

The town’s own source of revenue – local taxes– is only two to three hundred million yen, less than one-tenth of total revenue. This places severe limits on any attempt to construct or improve public facilities and infrastructure. In fact, one-fourth of the town’s revenue, 1.1 billion yen, comes from the grant-in-aid for this fiscal year, and the town has also been receiving large sums from Chugoku Electric since 2007.7 A new hot spa facility will open in December 2011, and two other facilities are planned, spending over 1 billion yen of the grant-in-aid. The building plans have been criticized by the opposition as so-called “hakomono” (public work projects) politics, and the town’s financial future – in terms of operating costs – is in limbo as the national policy on building new power plants has been called into question since the Fukushima disaster, hence the future of the grant-in-aid is also in danger. With the grant-in-aid, the town introduced bus subsidies for senior citizens as well as free medical care for the residents. It also distributes shopping coupons worth 20,000 yen per resident, by using 7.4 million yen from the Chugoku Electric contribution. Significant portion of the grant-in-aid is also used for the PR purposes of nuclear power plants.8

The power plant has been the major issue in the town’s mayoral and assembly elections for three decades. Supporters of the plant have won the past nine mayoral elections, most recently the mayoral election held on September 25, 2011, as well as the past seven assembly elections. Supporters thus argue that it is the democratic will of the people to build the plant, while recognizing how deeply the town is divided and how human relations remain broken in the community because of the power plant. In addition, the paper views nuclear power as a national policy issue. Japan’s national interest is at stake, and it is important to spread Japan’s superior, earthquake-resistant nuclear technology – for peaceful purposes – to developing nations. Using this same line of argument, they characterize the opposition as consisting of selfish people who are not thinking of the interests of their own community, and of Japan as a nation.

The election results, however, have been controversial at times. For example, in the town mayoral election of 1987, 155 people of the pro-nuclear power camp suddenly registered as residents of Kaminoseki Town just in time to be eligible to vote. Seven people were judged guilty and later convicted of irregularities. Oppositional citizens’ groups and media have reported numerous cases of bribery at town elections.9 According to photographer Nasu Keiko, Chugoku Electric spent an extraordinary amount of money for entertaining town officials, business owners and powerful residents of the town, and held frequent tours to the existing nuclear power plants.10

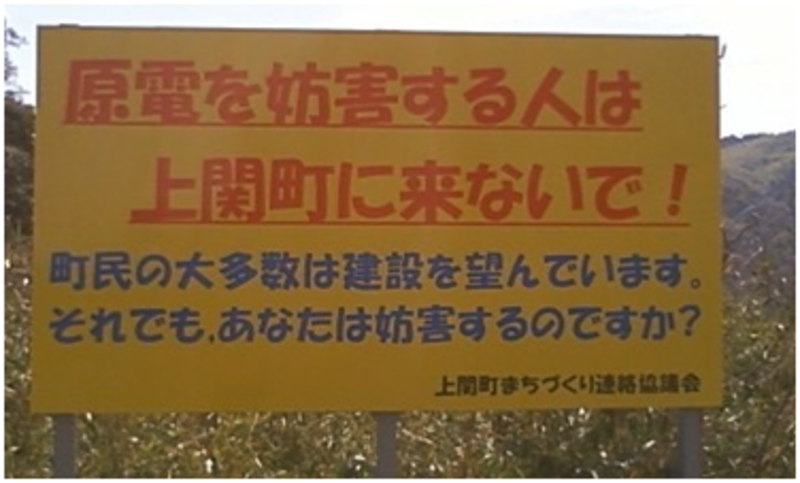

Recently, Jiji Hyōron has claimed that the main force within the opposition has shifted from local residents to outsiders, and that outsiders are committing illegal acts. The paper styles them as “gangs” who commit “terrorist actions.” Jiji Hyōron argues that the residents of Iwaishima, along with self-proclaimed “environmentalists” – i.e. outside activists such as the “Rainbow Kayaking Team,” are blocking the construction of the plant illegally and creating a nuisance. The same criticism of outsiders coming into town to engage in anti-nuclear plant activities is seen in leaflets and signs made by a residents’ organization supporting the plant.

|

Sign posted in the town of Kaminoseki, stating “Those who obstruct the construction of the nuclear power plant, don’t come to the Town of Kaminoseki! The majority of town residents want the construction. Despite this, do you still obstruct it?” Photo from a proponent organization, Kaminoseki Town Development Council /Kaminoseki Machizukuri Renraku Kyogikai. Source.11 |

The paper also criticizes the police and Coast Guard for doing nothing to stop the protests. Editor-in-chief Yamaguchi told me that the strategies of the opposition are problematic, because “in Iwaishima, where ninety percent of the residents are said to be the opposition, there is pressure on the ten percent supporters, as well as those who occupy the middle-ground, which keeps them from expressing their opinions freely.”

Hearing Mr. Yamaguchi’s stories, I could not help thinking of the Iwaishima residents’ claims, available both in the films and on the internet that the proponents acted unfairly. That is, both sides seem to have similar complaints about the other, illustrating the intense emotions that have built up during 30 years of conflict that has divided the local community.

Jiji Hyōron has also been extremely critical of reports on the Kaminoseki controversy in the mass media. To Yamaguchi (in contrast to opponents of nuclear power, who may think the opposite), the media reports lean too much toward the opposition. For him, the films on Iwaishima – such as Ashes to Honey and Houri no Shima – are propaganda representing outsiders’ opinions. He found the beautiful images of “nature” in those films to be manipulative tools of the opposition. “Nature” can be beautiful, he told me, but at the same time, it is dangerous – which is the painful reality that we all faced when we saw the tsunami on March 11. He insists that “humans have to live in harmony with it.”

Ashes to Honey reported on Iwaishima’s plan to achieve energy self-sufficiency without nuclear power. Yamaguchi’s response was that the plan might be interesting, yet he sees the key purpose of advocacy of natural energy to be a political one: to stop the Kaminoseki plan, rather than to promote environmental concerns. He sees “nature” as a tool used by the opposition, without offering a substantive explanation of their own beliefs. He also poses a major question: if sustainable natural energy could be made feasible on that tiny island with 500 residents, would it misleadingly convince people that the entire town of Kaminoseki, and Japan as a whole, could be supported in that way? The question of feasible alternatives to nuclear power is now being posed with increasing urgency in post-Fukushima Japan.

The Kaminoseki issue after 3/11

Since March 11, a number of arguments in support of the plant – on the prosperity of communities with a power plant, on the safety of Japan’s advanced nuclear technology – have lost credibility for many people. While the construction of Kaminoseki was halted on March 15 due to inquiries by the Town of Kaminoseki and Yamaguchi Prefecture, Chugoku Electric has continued digging and exploration. But the governor of Yamaguchi prefecture stated in the prefectural assembly meeting on June 27 that he would not approve an extension of Chugoku Electric’s sea reclamation permit at present on the grounds that the national governmental policy on nuclear energy and the safety measures for nuclear power plants have not yet been presented.

Likewise, Mayor Kashiwabara of Kaminoseki said in the assembly on June 21 that the plan to construct the Kaminoseki nuclear power plant might face extreme difficulty as the national government is reexamining its nuclear energy policy, and he has to consider how to develop the town without a power plant, given that the future of financial resources for nuclear energy remains unclear.12 Moreover, some local assemblies in surrounding cities and towns are petitioning to halt construction of the Kaminoseki plant, the first being the city of Shunan passed unanimously on May 27. Eight surrounding cities within a 30km radius of the planned Kaminoseki plant site followed in their footsteps, including Yanai, which is within 20 km of the plant and was to receive government aid for its construction.

I met again with editor-in-chief Yamaguchi of Jiji Hyōron in late June of this year. He expressed surprise over the Fukushima accident: he had expected the problems resulting from the accident to be resolved much sooner. It was already obvious from its coverage that Jiji Hyōron has been criticized by readers for its continued promotion of construction. He admitted that the situation has been stressful. Some readers criticized Jiji Hyōron and canceled their subscription. In a particular instance of bad timing, at the time of the Fukushima Daiichi accident, the paper was running a special series hailing the Kaminoseki plant and nuclear energy.

I could see from his writings that Yamaguchi, who has been the main reporter for the paper dealing with the power plant, is deeply frustrated. He characterizes the ongoing situation as an “overly emotional reaction” by the Japanese public and the media, and argues for the necessity of propagating “correct” information in order to avoid panic. The paper explains that the unexpected scale of the tsunami, not the earthquake, was the reason for the Fukushima accident, and the basic method of controlling nuclear hazards remains the same.13 It also claims that no serious harm to human health as a result of radiation has been reported so far.14 Jiji Hyōron asks, “Nuclear technology contributes to the advancement of our businesses, industries, medicine, lives, among others, and we should use this accident as a lesson and a challenge to pursue further technological innovations. Isn’t this Japan’s way to contribute to the world?”

Yamaguchi admits that the present situation is extremely difficult for promoters of the Kaminoseki plant – and for supporters of nuclear energy in general. He anticipates that more nearby cities and towns may issue statements against the plant. When asked to write articles or conduct interviews, some specialists who have supported nuclear energy now avoid doing so because they know they will be harshly criticized.

The newspaper has received phone calls from people who report seeing the films on Iwaishima. Yamaguchi seeks to engage them in conversation, and says that many know little about the situation beyond what has been covered in the films. The films – and the presence of outsiders in the protest movement – have also added complexity to the human relations, he said. Before the films and other public attention to the Kaminoseki issue, Yamaguchi could at least talk to a few of the protesters at Iwaishima. Despite different stances toward the power plant, they at least shared the overriding goal of revitalizing their local community. Now, with outside activists coming in, it has become even more difficult to hold discussions within the local community.

Furthermore, Yamaguchi wonders how much opponents from outside understand the reality of Iwaishima and Kaminoseki. He described the rapid aging and the unwillingness of young people to live and work on the island. I mentioned the many empty houses in Iwaishima, and he said there are many empty houses in other parts of Kaminoseki town, too.

|

An empty house in Iwaishima (photo by the author). |

Iwaishima, however, faces with the most serious lack of young people, because of its geography as an isolated, hilly island. When visiting the island, I also noticed that due to the hills and narrow roads, cars cannot go near the houses. With the rapid aging of residents, the lack of revenue is extremely pressing, and the island still lacks basic infrastructure. For example, many of the elderly live alone in houses without flush toilets.15 The depopulation of Iwaishima, Yamaguchi repeated, is much more serious than in other parts of Kaminoseki, but the entire area is struggling.

|

Narrow road in hilly Iwaishima (photo by the author). |

Yamaguchi continued that people who were forced into extreme economic hardship were committing suicide in Fukushima even as we spoke. In contrast, he said, nobody had yet died from the radiation leaked from the Fukushima Daiichi plant. What should we do to resolve the issue that exists right in front of us, now? He thinks that nuclear energy is only a temporary and partial solution, and that other methods using advanced technology need to be developed. Yet the question is what we can and should do now. The promoters of nuclear power plants have been accused of promoting the plants out of a desire for money. Money is undeniably necessary, especially in a community facing such a serious lack of revenue. It is, however, also true that despite lack of revenue and young people willing to live in the island, the vast majority of the Iwaishima residents continue to oppose construction of the Kaminoseki plant, and for them, Yamaguchi might be considered the outsider. He thinks, however, that given the serious lack of tax revenue, it is likely that more people are badly in need of and would like to receive compensation money for accepting the plant, but dare not openly say so because of community pressure.16

Thinking About Nuclear Energy Through the Lens of the Kaminoseki Controversy

The irony for Yamaguchi is that he has long tried, both as a journalist and as an activist, to convey to Japan’s urban majority the resource differential that exists between the urban and the rural populations, which is referred to as “chiiki kakusa”.17 The urban majority is located far from nuclear plants while using large quantities of nuclear power. Now, finally, with the Fukushima disaster, urban residents have become aware of crushing rural poverty, though only dimly. “Thirty years was too long, and everyone wants to have the issue resolved,” Yamaguchi said. Yet, even if the power plant is not constructed, he would like to have a “soft landing.” I asked him what he meant by “soft landing.” His answer was that if the power plant is not constructed, there should be alternative measures to reconstruct the local economy and community. He would like everyone to understand the reality of the local “ricchi” (construction site) community. Not building the plant cannot be the last word. Future discussion has to lead to alternative policies to shape the rural areas, and the responsibility should not be limited to the local government and residents.

Since March 11, the nuclear power debate has sharpened. Yamaguchi and other proponents of nuclear power insist that it is essential for Japan’s production of electricity and to remain competitive with other nations in nuclear technology. Unlike many other conservative proponents of nuclear energy who view Japan’s nuclear energy program as a stepping stone toward production of nuclear weapons, he differentiates atomic weapons and nuclear energy.18 But what is most distinctive is the fact that he highlights the harsh reality of rural communities, and this has been most persuasive for a struggling rural region located not far from Hiroshima. At least until March 11.

The power plant, as well as the socio-economic structure in which struggling rural communities are left without the resources that would allow them to share in the national affluence, is at the heart of long-lasting, serious conflicts between urban and rural society. While it may be easy for opponents of nuclear energy – especially urbanites living far away from the plant sites – to criticize claims made by supporters, it seems crucial to keep in mind the harsh reality faced by local residents of the plant sites. The critics of nuclear energy –especially those who are outside of ricchi – have the responsibility to seriously consider the question of the economic hardship facing rural communities, and the growing urban-rural gap. Lack of revenues and basic infrastructure always come up as reasons for siting a power plant by proponents including the government and industry. Once a community starts to accept grants-in-aid and donations, it becomes more and more difficult for it to seek alternative ways to be independent from such sources. The case of Kaminoseki with the new hot spring facility illustrates the problem; without the aid and donations, it becomes difficult to continue operation of the facility. Addressing the issue of economic hardship, lack of infrastructures as well as suggesting alternatives to nuclear-related funds provide strategies for resisting threats from government and industry about the deprivations an antinuclear policy would bring. The issue also brings up profound questions of equitable tax burdens, economic growth, environmental health, the right to a decent livelihood, and power differentials between the urban and the rural. And most especially, what are we citizens willing to do to create a society that effectively addresses such inequities?

Postscript: After the Kaminoseki Mayoral Election of September 25, 2011

On September 25, 2011, the Kaminoseki mayoral election was held, and the incumbent, Mayor Kashiwabara Shigemi who has supported the power plant construction, defeated the opposition candidate, Yamato Sadao of Iwaishima, the leader of the anti-Kaminoseki plant movement. The election attracted nationwide attention as the first election at a new construction site (ricchi) since the Fukushima Daiichi accident. Mayor Kashiwabara won for the third time. With 67.4% (1,868 votes) of the votes, he had twice the total of his opponent, Yamato Sadao (905 votes). Kashiwabara won 0.6% more votes than in the previous election as 87.55% of voters cast ballots.

|

Mayor Kashiwabara with supporters after his election Source. |

I asked Mr.Yamaguchi immediately after the election for his thoughts. He said, “I think we have to bring an end to the unproductive debate between promoters and opponents, or nuclear power and alternative energy (such as solar). We should begin realistic multi-dimensional discussion of the larger picture of energy supply, as well as our energy policy as a whole.” He continued, “in Japan, the structure of electricity supply is currently, ‘30% nuclear energy, 60% thermal, 8% hydro, 1% geothermal and alternative sources, and 1% other.’” Looking ahead to 2030, he went on, “we should keep the percentage of nuclear energy as it is, while “renewable energy (including hydro) supplies 20%, nuclear energy 30%, thermal 40% as well as 10% from energy conservation.” He concludes, “going beyond the current divisions and getting knowledge to the people of Japan is the key for Japan after the earthquake.” His view, favoring continued dependence on nuclear energy for a substantial portion of Japan’s energy, is at odds with recent opinion polls, and the direction charted by former Prime Minister Kan Naoto calling for sharp increase in renewables and reduction of nuclear power, although the direction remains unclear under his successor Noda Yoshihiko. In addition, serious questions remain whether the technological “knowledge” that Yamaguchi repeatedly highlights can guarantee the safety of nuclear power, above all in the world’s most earthquake-prone nation.

The result of the mayoral election demonstrates how difficult it is for anti-nuclear forces to win an election in Kaminoseki and perhaps in many other struggling rural communities, even at this moment when the Fukushima Daiichi Power Plant’s accident is ongoing and public opinion polls reveal the surge in anti-nuclear power sentiment.19 In blogs and twitter, I observed many posts expressing shock and surprise from the opposition to the election result, and criticisms of the activism and campaign tactics from both proponents and opponents of nuclear power.20 Among the criticisms, the opposition was again characterized as “outsiders” and “professional activists” as well. This line of critique is common to anti-nuclear energy movement in local communities, and it became even more visible following the surge of anti-nuclear demonstrations.21 Especially regarding nuclear energy and power plants, however, it is difficult – and likely impossible – to draw a clear line between “insiders” and “outsiders,” given the wide range of radiation effects once an accident occurs.22 The residents of the town of Kaminoseki are obviously not the only ones who would be subject to radiation exposure, if a major accident were to occur. The proponents, such as the Kaminoseki Town Development Council (Kaminoseki Machizukuri Renraku Kyōgikai), also interpret the election result as a sign of residents’ will to have an experienced mayor in difficult times, and they endorse Mayor Kashiwabara’s statement highlighting the difficulty of operating the town’s policies and finances without the government’s grant-in-aid for the Kaminoseki plant.

Media reports on the election, however, reveal that Mayor Kashiwabara’s campaign did not rest exclusively on the pledge to build the Kaminoseki plant. Kashiwabara, while supported by seven pro-nuclear organizations, did not change his long-term stance as a proponent of nuclear power. In this campaign, however, he rarely expressed support for the plant’s construction.23 Indeed, he expressed willingness to work on alternative plans in the event the power plant is not built due to changes in national policy in the wake of Fukushima. As of September 2011, all but 11 of Japan’s 54 nuclear power plants are closed pending stressed tests, and while the government has expressed willingness to restart the closed plants, the prospect is still unclear in the face of powerful opposition.24 All the more, the plan to build 14 new nuclear power plants is up in the air after the Fukushima Daiichi accident, and Prime Minister Noda stated in a press conference that it is realistically difficult to build new power plants.25 Nihon Keizai Shimbun reports that even one of the leading proponents of Kaminoseki said, “I know that there will be no new nuclear power plant in this situation.”

The result of the recent Kaminoseki mayoral election has forced those in the opposition to reconsider how to build their movement against nuclear energy in struggling ricchi (construction site) communities that have long relied on grants-in-aid and donations from electric corporations. It also posed a major question for all of us – both promoters and opponents, the residents of the town and those who live outside of the ricchi. How are we to look beyond divisions over nuclear power to consider both the broader parameters of Japan’s energy policy and the future of Kaminoseki and all other struggling rural communities, particularly those that have long depended on funding from the nuclear power companies and their supporters in government?

Tomomi Yamaguchi is an assistant professor of Anthropology at Montana State University. Her recent publications are “The Fukushima Daiichi Accident and Conservatives’ Discourse about Nuclear Energy and Weapons in Japan,” Anthropology News (October 2011), “The Pen and the Sword: Ethical Issues Surrounding Research on Pro-war Right-Wingers in Japan,” Critical Asian Studies, Vol.42, No.3, August 2010. Her co-authored book in Japanese (with Ogiue Chiki and Saito Masami), Feminism and “Backlash” (provisional title) is forthcoming in 2012. Her current research project involves nationalism, racism and xenophobia in contemporary Japan, particularly on the “Conservatives in Action” movement.

I would like to express my special thanks to the editor-in-chief of Jiji Hyōron, Yamaguchi Toshiaki for spending time and sharing his stories and insights with me, despite our different stances toward nuclear energy. I would also like to thank Norma Field, Bethany Grenald, Yuki Miyamoto and Mark Selden for their comments and suggestions on this article.

Recommended citation: Tomomi Yamaguchi, ‘The Kaminoseki Nuclear Power Plant: Community Conflicts and the Future of Japan’s Rural Periphery,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 41 No 3, October 10, 2011.

Articles on related subjects

• Jeff Kingston, Ousting Kan Naoto: The Politics of Nuclear Crisis and Renewable Energy in Japan

• Chris Busby and Mark Selden, Fukushima Children at Risk of Heart Disease

• Hirose Takashi, Japan’s Earthquake-Tsunami-Nuclear Disaster Syndrome: An Unprecedented Form of Catastrophe

• Winifred A. Bird and Elizabeth Grossman, Chemical Contamination, Cleanup and Longterm Consequences of Japan’s Earthquake and Tsunami

• Kodama Tatsuhiko, Radiation Effects on Health: Protect the Children of Fukushima

• David McNeill and Jake Adelstein, What happened at Fukushima?

• Koide Hiroaki, The Truth About Nuclear Power: Japanese Nuclear Engineer Calls for Abolition

• Chris Busby, Norimatsu Satoko and Narusawa Muneo, Fukushima is Worse than Chernobyl – on Global Contamination

• Yuki Tanaka and Peter Kuznick, Japan, the Atomic Bomb, and the “Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Power”

• Paul Jobin, Dying for TEPCO? Fukushima’s Nuclear Contract Workers

• Say-Peace Project and Norimatsu Satoko, Protecting Children Against Radiation: Japanese Citizens Take Radiation Protection into Their Own Hands

See other articles on Fukushima in the What’s Hot section of the Asia-Pacific Journal and a complete list of articles on 3.11 Earthquake, Tsunami and Atomic Meltdown.

Notes

1 See Norma Field “The Symposium and Beyond” for more information on the symposium (link). A video on the symposium is also available via the Atomic Age blog.

2 The trailer in English of Ashes to Honey can be viewed here.

3 See Kamanaka Hitomi (Introduced and translated by Norma Field), “Complicity and Victimhood: Director Kamanaka Hitomi’s Nuclear Warnings,” and Kamanaka Hitomi, Tsuchimoto Noriaki and Norma Field, “Rokkasho, Minamata and Japan’s Future: Capturing Humanity on Film”, for more information on Kamanaka’s works.

4 In contrast, Rokkasho Rhapsody by Kamanaka Hitomi includes interviews with supporters of the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant in Aomori prefecture while also describing the often tense interactions and the feelings of isolation of those who continue to oppose the plant (which has already been constructed) within the community.

5 The Rainbow Kayaking Team explains their activity in their blog (in Japanese)

6 See Pomper, Dalnoki-Veress, Lieggi and Scheinmann “Nuclear Power and Spent Fuel in East Asia: Balancing Energy, Politics and Nuclear Proliferation” concerning the problem of spent fuel and reprocessing.

7 Jiji.com 9/25/2011”The Grant-in-aid for nuclear power plants consists of one-fourth of the town’s budget – Kaminoseki-cho of Yamaguchi prefecture under difficult financial operation.”

8 Chugoku Shimbun 10/1/2011 “The Grant-in-aid for the Town of Kaminoseki – Asking the same amount as before.”

9 Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center’s newsletter Vol. 425 (11/1/2009) has a timeline on the Kaminoseki controversy, and indicates the 1987 case. Link.

Chōshū Shimbun, a leftist /communist (independent of the JCP) paper that takes an oppositional stance to the Kaminoseki plant, also writes in detail about past bribery incidents in the town of Kaminoseki by Chugoku Electric. 5/15/2003 “The Framework of Bribery by Chugoku Electric.”

10 Nasu Keiko. Chūden-san Sayonara: Yamaguchi-ken Iwaishima Genpatsu to Tatakau Shimabito no Kiroku (Good-Bye, Chuden-san: The Record of Islanders Figting Against a Nuclear Power Plant in Iwaishima). Tokyo: Soshisha, 2007 :35-37

11 A leaflet by Kaminosekicho Machizukuri Renraku Kyogikai, criticizing outsiders coming to protest against the plant’s construction, is also posted in the organization’s blog.

12 Asahi Shimbun, “Thirty-Years of Conflicts: Kaminoseki at the Crossroad.” 6/28/2011. Also see McCormack “Hubris Punished: Japan as Nuclear State.”

13 See Adelstein and McNeill for criticism of the view that the tsunami caused the accident. They quote TEPCO workers saying that the earthquake caused significant damage to the pipes and gas tanks prior to the tsunami. Link.

15 According to Yamaguchi, thanks to the very modest national pension that many of the elderly residents of Iwaishima receive, they can survive – though barely. The lack of infrastructure is extremely serious, particularly with the rapidly aging population.

16 See Oguma, Eiji. “The Hidden Faces of Diaster: 3.11, the Historical Structure and Future of Japan’s Northeast” for the similar issues of population decline and economic structure in Tohoku.

17 Jiji Hyōron is distributed beyond Yamaguchi prefecture, especially to conservative politicians. After March 11, Jiji Hyōron published a theme issue on nuclear energy as a booklet, Yūsen. Yamaguchi also contributes articles in other conservative publications.

18 An interesting example of the intentional dissociation between nuclear weapons and nuclear energy is the use by Yamaguchi and other Kaminoseki proponents of the term, “genden,” rather than “genpatsu,” for nuclear power plants. Yamaguchi Governor Nii Sekinari, also used the term, “genden,” until August this year, when he announced that he would use the common term “genpatsu.” (Yamaguchi Shimbun, 8/2/2011) According to Yamaguchi, one reason for the avoidance of the term, “genpatsu,” is that it sounds like “genbaku,” the atomic bomb.

19 See Jeff Kingston on the decline of the Japanese public’s support on nuclear energy and the rising support for a policy to phase out nuclear energy with a goal to abandon it.

20 For example, Chōshū Shimbun, a Shimonoseki-based leftist paper in opposition to the Kaminoseki plant, criticized the opposition candidate’s campaign strategy. Chōshū Shimbun, “The result does not mean victory for the proponents.” 9/26/2011 On twitter, freelance journalist, Ishii Takaaki criticized outsiders’ interference in local politics as the major reason why the opposition could not gain significant support, even at this particular election. Link.

21 For example, Ishihara Nobuteru of LDP called the anti-nuclear activists of Iwaishima as “outsiders” and “Chukaku-ha”, adding that the anti-nuclear rally of June 11 in Shinjuku was led by “professional activists” of various sects. Mainichi Shimbun (Kyushu local coverage) “Yamaguchi, Kaminoseki Plant Construction Plan: Ishihara ‘Impossible to construct for the next 10 years,’ ‘The opposition movement is anarchist.’” 6/19/2011

22 For the spread of radiation related to the accidents in Chernobyl and Fukushima, see Busby and Selden, “Fukushima Children at the Risk of Heart Disease.” Selden points out that radiation is not necessarily limited to concentric circles or evacuation zones defined by the state, and may easily transcend national borders through the air and water.

23 Nihon Keizai Shimbun “Kaminoseki, A step forward for united town development efforts: Overwhelming victory for Kashiwabara.” 9/27/2011; Chōshū Shimbun “The result is not victory for the proponents.” 9/26/2011

24 Asahi Shimbun “Minister of National Strategy moving forward with the resumption of nuclear power plants” 10/1/2011

25 Jiji.com “High hurdle for constructing new nuclear power plants: even with election victory by the proponents.” 9/25/2011