Ko Tae Mun, Ko Chung Hee, and the Osaka Family Origins of North Korean Successor Kim Jong Un

Kokita Kiyohito, Tessa Morris-Suzuki and Mark Selden

The following article by Kokita Kiyohito, on the family origins of Kim Jong Un, the leader designate of North Korea, is illuminating above all for the language, assumptions and treatment of issues related to North Korea in contemporary Japanese media, including the Asahi. Two brief commentaries locate some of the issues in broader perspective. The headline and article are taken from the Asahi’s weekly Aera; photos have been provided from other sources. The major story addressed in the commentary by Tessa Morris-Suzuki is the collaboration of the Japanese government and the International Red Cross in arranging the migration of more than 93,000 Korean residents of Japan, who had been deprived of Japanese citizenship following Japan’s wartime defeat, to North Korea. Mark Selden examines a range of issues related to the perspective of the Japanese journalist on Zainichi Koreans and North Korea.

Osaka Black Mark in Kim’s Life?

Kokita Kiyohito

Osaka–Without fail, North Korea’s propaganda machine deifies any location associated with the Kim dynasty, but the birthplace of the mother of future leader Kim Jong Un is unlikely to be accorded such reverence.

In any event, the sad history of her family in Osaka is hardly the stuff of legend.

Specifically, Ko Young Hee came from Osaka’s Tsuruhashi district, an area that for decades has had a thriving Korean community.

|

Tsuruhashi Shopping Center, Osaka, today |

According to a resident of the neighborhood, someone linked with North Korea recently came to check on the site of her birthplace, long an empty lot.

Kim Jong Un is the third son of North Korean leader Kim Jong Il and the grandson of Kim Il Sung, the founder of North Korea. In September, Kim Jong Un was anointed heir apparent.

His mother was born in June 1953, a month before a cease-fire agreement was reached in the Korean War.

Her father was called Ko Tae Mun. He was born in 1920 in Jeju island when the Korean Peninsula was under Japan’s colonial rule. Jeju Island is now part of South Korea.

Ko Tae Mun came to Japan when he was 13 to join his father.

An elderly resident of Tsuruhashi said a famous black market in the district in the immediate aftermath of World War II was controlled by Korean nationals.

“Many of those individuals walked around as if they owned the place. The Japanese seemed to take a step back. (Ko), who would use a nearby bathhouse, always walked around with a proud bearing.”

Ko learned judo from a Japanese while living in Osaka.

The resident recalled: “Ko’s wife did sewing at home. Many of the Koreans living here came from Jeju. His wife was a hard worker, but her husband was always drinking and doing as he pleased. There were many households like that.”

Ko often visited a dojo that was on the first floor of a building that housed a newspaper for a Korean organization on the second floor.

A Korean national in his 80s who worked at the newspaper said: “Four Korean nationals often gathered at the first floor judo hall to teach judo. It was said that when all four were around, they had nothing to be afraid of.”

One of those individuals was Ko.

The division in the Korean Peninsula led to the creation of South Korea and North Korea in 1948.

Perhaps because he was having difficulties making a living solely from judo, Ko in 1956 started his own professional wrestling group with ethnic Korean businessmen serving as sponsors.

That was the era in which Rikidozan, himself a Korean national, sparked a wrestling boom in Japan, then desperate for local heroes after its defeat in war, by staging bouts in which Japanese usually defeated their much larger American opponents.

Rikidozan concealed his Korean roots and became very wealthy as well as a hero to the Japanese. Ko wrestled under the name of Daidosan after the river that flows through Pyongyang.

However, his wrestling group never took off, and Ko disbanded it soon after.

In 1961, the family boarded a ship in Niigata bound for North Korea under a program begun in December 1959 by Kim Il Sung to repatriate Korean nationals living in Japan.

The move to North Korea was for more than simply economic reasons.

As part of a plan to host an international sports event for newly developing nations, Kim Il Sung wanted to create a judo association in North Korea. As far as he was concerned, the man for the job was Ko.

A former high-ranking official of the Pyongyang-affiliated General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (Chongryon) said, “(Two officials) of a sports association affiliated with Chongryon in Osaka were given instructions, and they approached Ko and asked him to return to North Korea.”

Although Ko was only a minor pro wrestler in Japan, his move to North Korea would eventually lead to him being referred to as the father of North Korean judo.

Another Korean national who also moved to North Korea learned judo from Ko and would later flee the North for South Korea.

The individual once said, “Those who built the foundation of North Korean judo were all Korean nationals who moved from Japan. Ko’s daughter, Young Hee, resembled her mother and was slim and very pretty. She would often visit the judo hall.”

Having become the daughter of an influential figure in North Korean judo, Young Hee in around 1970 joined the Mansudae Art Troupe as a dancer.

It was there that she caught the roving eye of Kim Jong Il. While Korean nationals who returned to North Korea from Japan were often discriminated against, Young Hee experienced a Cinderella story of sorts.

In 1973, she came to Japan as the lead dancer of the Mansudae Art Troupe.

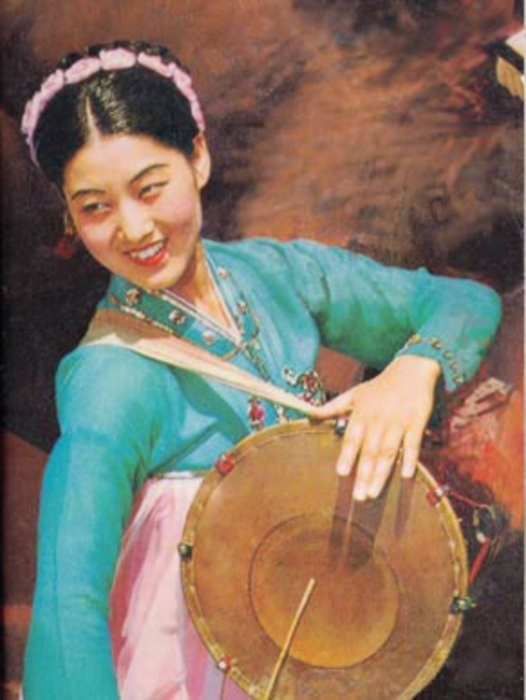

|

Ko Young Hee performing with the Mansudae Art Troupe |

An individual with ties to Korean nationals said, “Her visit to Japan was a present from Kim Jong Il. He basically told her to go to the Japan of her birth and buy whatever she wanted. She was treated very specially and those around her were very nervous about not upsetting her.”

Ko Tae Mun died in Pyongyang in 1980. Ko Young Hee gave birth to three children. She died of cancer in 2004, having reached the pinnacle of North Korean society.

North Korea will likely make a huge effort to create a revolutionary legend around Jong Un. People in the Korean community in Japan are in agreement that little mention, if any, will be made of Tsuruhashi, or the ties to the district of both his mother and her family.

The history of the family in Japan, including Ko Tae Mun’s failure as a pro wrestler, does not have the makings of a good legend, they say.

What could be included in the legend is the fact that Ko Tae Mun was born in Jeju. In 1948, islanders clashed with the right-wing South Korean authorities. The conflict resulted in numerous fatalities, and some islanders fled to Japan.

In around 2003, a TV drama about the incident was broadcast in North Korea. That was at a time when Ko Young Hee’s political influence was growing.

A former high-ranking Chongryon official said a legend about Kim Jong Un could be created along the following story line:

“Ko Tae Mun carried on the will of Jeju islanders who fought bravely under the guidance of Kim Il Sung. After fleeing to Japan, he returned to North Korea to be embraced by the greatness of Kim. Ko gave up his life to serve as a soldier for Kim. Kim Jong Un would be an individual who carried on the great revolutionary bloodline from Jeju.”

Tsuruhashi would have no place within that legend.

A source in the Korean community in Japan said, “Ko Tae Mun’s relatives still live in Osaka. They are not involved with Chongryon. Even if you talked to them, they will tell you nothing. They have been told to keep quiet by North Korea.”

This article appeared in the Asahi Shimbun Weekly Area on December 1, 2010.

Commentary

Ko Young Hee and the “Repatriation” of Ethnic Koreans from Japan to North Korea

Tessa Morris-Suzuki

The story of Ko Young Hee is an intriguing and little known part of the history of the mass “repatriation” of ethnic Koreans from Japan to North Korea. Ko Young Hee and her family were among 93,340 people (most of them ethnic Koreans) who were relocated from Japan to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, North Korea) following the signing of a repatriation agreement between the Japanese and North Korean Red Cross Societies in 1959. The Ko family left at the height of the exodus: though repatriation continued until 1984, over 70,000 of those who left did so before the end of 1961. Most, like Ko Young Hee’s family, originated in the southern half of the Korean peninsula, and a particularly large number came from Jeju: an island with a history of large-scale emigration to Japan, and the site of a 1948-49 uprising against the South Korean government which was suppressed with great force.

|

Boarding a ship for North Korea |

What is unusual about the Ko family’s story is their destiny once they arrived in North Korea. As is now known, the background to the “repatriation” is a dark story of pressures and intrigues on both sides. Japanese bureaucrats and some politicians played a very active role behind the scenes in creating the scheme for a mass repatriation, and in encouraging Koreans in Japan to leave for a “new life” in a North Korea which most had never seen before. An important factor on the Japanese side was majority prejudices against a minority seen as lawless and potentially subversive. (The widespread perception that Koreans had tried to “lord it” over the Japanese majority in the immediate aftermath of Japan’s defeat in war was an important element in these prejudices). Meanwhile, the DPRK government, via the pro-North Korean organization Chongryun [Sōren in Japanese] spread glowing propaganda about the rosy life that awaited “returnees” in the socialist fatherland. In some cases, Chongryun was instructed specifically to encourage the repatriation members of the community with specialist skills which would help North Korean development, and this seems to be the case with Ko’s father.

Most Koreans from Japan, however, quickly found that their lives in North Korea were far from the propaganda image. Many were sent to work in remote mining or rural areas, and came to be assigned to the lowest levels of the DPRK’s complex (and secret) social ranking system – regarded as unreliable citizens, and therefore barred from prestigious jobs. There were exceptions however – and Ko Young Hee was the most remarkable of all, becoming the wife of Kim Jong-Il and mother of his designated successor Kim Jong-un. Many members of the Korean community in Osaka remember the Ko family, and, with Ko Young Hee’s relatives still living in Japan, there should be the basis for a link between the North Korean heir apparent and his mother’s birthplace. It is symbolic of the tragedy of Northeast Asia today manifest in the continuing Japan-North Korea clash, that this link may never be celebrated, but rather (as in the interviews reported here) spoken of uneasily, almost in whispers.

Tessa Morris-Suzuki is Professor of Japanese History at the Australian National University and an Asia-Pacific Journal Associate. She is the author of Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War. Her two most recent books are To the Diamond Mountains: A Hundred Year Journey Through China and Korea, from which this article is excerpted, and Borderline Japan: Foreigners and Frontier Controls in the Postwar Era.

The Asahi portrayal of Zainichi Korean life in Osaka and the Family Origins of Kim Jong Un

Mark Selden

From the article’s headline through the treatment of Zainichi history in Osaka, the migration of Korean families to North Korea, and the family history of Ko Tae Mun and Ko Chung Hee, the present article is indicative of the fraught relations between Japan and North Korea and the continued legacy of prejudice against Korean residents of Japan.

Take the headline: Osaka Black Mark in Kim’s Life? The article paints a portrait of Korean residents of Osaka that emphasizes their black market activities in the desperate years of the immediate postwar, a time when the Japanese government stripped Koreans of their Japanese citizenship, sought to deport many, and generally marginalized Korean residents who were among the groups hardest hit by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the firebombing of Tokyo, Osaka and other cities. No mention here, for example, of the fact that many Japanese survived the early postwar years via black market activities or any other contextualization of the Zainichi Korean experience.

Not only does the article quote an elderly Japanese resident who describes Korean control of the Tsuruhashi black market, but the interviewee bridles at the fact that Koreans, particularly those who dominated the black market, “walked around as if they owned the place,” and Ko in particular (by association) “walked around with a proud bearing,” though the article does not directly charge him with black market activity.

The brief mentions of the US-Korean War are equally interesting. I am particularly interested in the use of sentences with no subject: “The division in the Korean Peninsula led to the creation of South Korea and North Korea in 1948.” No agents at work here. If my recollection is correct, the division did not simply “happen”. Rather, then army officer, later Secretary of State, Dean Rusk drew a line across a map at the 38th parallel and the US then persuaded the Soviet Union to accept the demarcation as a means of preventing armed conflict between the two former wartime allies. And placing Seoul and the majority of the Korean population under US rule. Indeed, the United States nowhere appears in the article’s several references to the Korean War.

That includes the discussion of Jeju, the island off South Korea that produced the largest number of Korean migrants to Japan including Ko. The author states that “In 1948, islanders clashed with the right-wing South Korean authorities. The conflict resulted in numerous fatalities, and some islanders fled to Japan.” Numerous fatalities? Indeed numerous, and the figures remain contested to this day. As Ko Sun Hui Kate Barclay and conclude, “Local records show 14,028 people [out of an estimated population of 300,000] were registered as killed or missing that day, and since many more deaths would not have been registered it has been estimated that 20-30,000 people were killed. (“Traveling through Autonomy and Subjugation: Jeju Island Under Japan and Korea,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, May 30, 2007, link.) Others have suggested higher casualties, cf. Wikipedia’s estimate of 14,000 to 60,000 (link). Once again, the agent is obscure: but we know that the major killings were carried out by ROK forces together with rightwing vigilantes. The article goes on to relate the fact that a North Korean documentary about the Jeju Island clash was aired in 2003, explaining this as “a time when Ko Young Hee’s political influence was growing.” However, the Jeju Uprising was (and is) a longtime staple of nationalist historiography in North Korea, which had no need for Ko’s political rise to record the events.

After presenting Ko as a drunk, the article allows that, in 1956, he “started his own professional wrestling group.” Why? “ . . . perhaps because he was having difficulties making a living solely from judo.” In a land in which entrepreneurship is routinely praised, Ko’s endeavor is painted in desperate colors.

The article is, in short, indicative of the difficulties that lie ahead in restoring North Korea-Japan relations to normalcy in the wake of the political movement to make Korean kidnapping of Japanese nationals in the 1980s the pivotal issue of Japanese diplomacy, and the eradication of consciousness of Japanese crimes against Koreans over the half century of colonial rule.

Mark Selden is a coordinator of the Asia-Pacific Journal. His most recent books are Japan’s Wartime Medical Atrocities: Comparative Inquiries in Science, History, and Ethics and China, East Asia and the Global Economy. Regional and Historical Perspectives. His home page is www.markselden.info

Recommended citation: Kokita Kiyohito, Tessa Morris-Suzuki and Mark Selden, Ko Tae Mun, Ko Chung Hee, and the Osaka Family Origins of North Korean Successor Kim Jong Un, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 1 No 2, January 3, 2011.