Young Japanese Temporary Workers Create Their Own Unions

Emilie Guyonnet

Translated by Ludwig Leibenguth

From the early 2000’s onwards, a new kind of trade unionism has been steadily gaining ground in Japan. While the country’s major trade unions are stagnating or losing workers, temporary workers, especially young people, have begun to create their own structures.

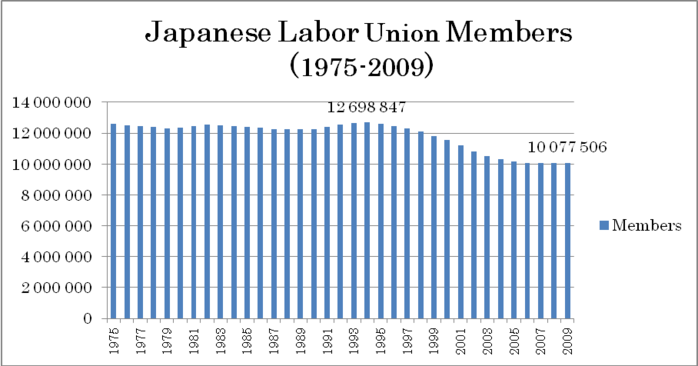

In contrast with the trend of deunionization prevailing in Japan (and many other countries) since the 1970’s, the number of unionized temporary workers rose from 400,000 to 700,000 between 2005 and 2009.1 Marginal though this may seem – Rengo, the country’s main trade union claims 6.8 million members – this trend is breathing new life into a defeated union movement: after remaining stagnant since 1975, during the “lost decade” beginning in the mid 1990s, union membership declined by 2 million to level off at 10 million people today. Moreover, the percentage of union members in the labor force declined steadily throughout the entire period from 35 percent in 1975 to less than 20 percent by 2008.

Source: Department of Health, Labor and Social Services, General Survey of Union Organizations, 2009. Graph by David-Antoine Malinas, Center for the Study of Social Stratification and Inequality, Tohoku University.

These precarious workers – many of them young people – assemble into rather small organizations. Some of them remain independent, while others affiliate with the major labor unions, which are beginning to seize upon the issue of precariousness in an attempt to curb their decline. That is the case of the Shutoken Seinen Union in Tokyo (SSU) – Tokyo Young Contingent Workers’ Union – which is affiliated with Zenroren, the second largest trade union federation in the country, closely linked to the Japanese Communist Party.

Shutoken Seinen is among the most active of the new unions and well illustrates their mode of operation. We met some of its members in Yokohama at a time when Nissan was holding its 2009 stockholders general meeting. Five of them sought to raise their grievances with Nissan shareholders on their way to the conference center. They sought to draw attention to the case of a young woman, hired by Nissan under a short-term labor contract three years previously, and then repeatedly renewed before being suddenly dismissed. The case exemplifies attempts by many companies to prevent workers from achieving the status and benefits of permanent employees.

Shutoken Seinen union members appeal to Nissan stockholders over the company’s employment practices, Yokohama, June 2009 |

The Yokohama scene might have raised few eyebrows elsewhere. But this is Japan. The ban on labor unions wasn’t lifted here until 1945, during the American occupation. Dogging each union activist’s footsteps was a security guard with a megaphone, warning anyone within hearing distance that handing out flyers on private property is a punishable offense – the property in question being the bridge leading from the subway station to the conference hall.2 From below, fellow union members were shouting messages of their own from a truck equipped with a loudspeaker.

Before the arrival of secretary general Kawazoe Makoto, the charismatic leader of the Shutoken Seinen Union, his colleagues had cautiously remained at a distance on the sidewalk, in the “public” zone. Only after lengthy negotiations could Mr. Kawazoe convince the chief of security to allow leafleting (trespassers are liable to jail sentences). At the same time inside the conference center, cheerful hostesses were welcoming the shareholders. They, too, might well have been on temporary contracts, like 34% of all Japanese workers.

“To raise one’s voice” is Mr. Kawazoe’s motto. In Japan, only a minority has the courage to do so. “By securing the payment of overtime, or the hiring of temps, our Union proved that individuals have rights. Before that, they used to leave rather than claim these rights,” he explains. The union’s success is undeniable: Shutoken Seinen has won 80 to 90% of all collective bargaining it initiates.3 Under Japanese law, any union member can request that collective bargaining negotiations be opened with his employer on his behalf. This is why the SSU made it possible for employees to join as individuals, whatever their status and the industry.

The SSU’s main strength is that it encompasses unionism and the civil society. On the one hand, it is affiliated with Zenroren. This provides the Union with an office, and access to the Diet through its communist members. On the other hand, SSU leaders are all members of the anti-poverty network, which brings together key figures from all three major union federations: Rengō, Zenrōren and Zenrōkyō, as well as other political entities of various political leanings, NGOs, and many lawyers. More than 90 organizations in all are represented. The anti-poverty network consistently hit the headlines during winter 2008-2009 when it set up “hakenmura” – tent villages – in Japan’s largest cities, to house laid-off temporary workers left homeless.4

“Our claims are articulated in terms of a struggle against discrimination and poverty,” explains Mr. Kawazoe. With good reason: 80% of his union’s members, whose average age is 31, live below the poverty line. “We also struggle against the prevailing view that individuals are responsible for their own problems and have to cope on their own”, he adds. He goes on to tell of a young man whose plight was so desperate that he had to beg a coin from a policeman to call the Union for help.

The Shutoken Seinen Union now has 400 members. “This is not a lot, but it keeps increasing: that’s up from 300 in 2009,” comments David-Antoine Malinas, assistant professor at Tohoku University. “Turnover is high; people don’t remain within the Union. That makes it more difficult to organize but doesn’t weaken the ‘Union spirit’ which is on the rise because members leave the Union with their problems solved.” The SSU also spreads through the creation of local branches outside of Tokyo and in districts within Tokyo.

Where does this new union come from? Its ten founding members are all former student activists of the “Jichikai”, the self-government organizations that were long centers of student activism.5 After graduating, they went on to work part-time for the same company, while organizing conferences. They draw inspiration from “Community Unions”, which are small local unions (about 100 members) created within Small and medium enterprises. Formed in the 1970’s and 1980’s, these unions brought together people who were outside standard employment frameworks: women, foreigners, part-timers, temps, etc.

With 400 members, the SSU is one of the largest young workers’ unions, but it is far from the only one. At the beginning of 2009, in just three months, 250 new independent unions of mostly young people sprung up, often with some help from the Japan Communist Party. Labor federations also played a part by setting up telephone help lines for temporary workers, to encourage them to unite. “We try to get temporary workers and regular employees to work together but it’s very difficult. Contingent workers often end up setting up their own structures,” says Fusei Keisuke, director of Zenroren’s international bureau. “At first, temps where denied access to labor unions.”

Many of the new unions are tiny, like the Freeter Union Fukuoka, on Kyushu, with 22 members. They are nevertheless effective. “The cases submitted to us typically involve unfair dismissals by small companies,” points out Ono Toshihiko, one of the founders of the Freeter Union Fukuoka. “We’ve never lost a single negotiation.”

Mr. Ono relied on the Japanese pacifist network, which found a new lease on life during the Iraq war in 2003. “That’s when I joined the civic movement. That brought me in contact with a lot of people, most of them older, but some of them my age,” explains Mr Ono. “During the protests against the Iraq war, we inaugurated a new style of demonstration with a DJ, which proved a great success with the young. We then split off to create our union.” The young translator also derived inspiration from protest movements in France and Greece: “a protest movement like that against the CPE (Contrat Première Embauche or first employment contract)6 in France would have been impossible in Japan,” he deplores.

According to Ono Toshihiko, the university is where it all begins: “When the university was being reformed in 2004,7 I tried to mobilize the students but they were too busy. The problem is that they don’t see themselves as freeters. Personally, I used to see myself as a freeter when I was a student because I had to work part time.” The word freeter (a coinage from the English word free and the German word arbeiter) is the Japanese term for young workers on precarious contracts. Many are students who work to pay for their education or to treat themselves to something special. The average annual tuition fee in Japan’s public universities is over 4,000 US dollars, but grants are scarce: only 25% of students receive financial aid.8 Most students have to take out loans from the Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO). But with the economic slowdown since the 1990s, more and more find themselves trapped in precarious jobs, heavily in debt, and unable to meet their commitments.

Fukuoka, where Mr Ono founded his union, is the gateway to Kyushu, the north of which, a mining region, is one of Japan’s four main industrial areas. Two hours train to the east is the city of Oita, home of a giant Canon factory and the birthplace of Mitarai Fujio, the powerful CEO of Canon and head of Keidanren, Japan’s main employers’ association. This is where we meet other young unionists, Kato Shuhei and his colleagues, who are former Canon employees.

Mr Kato established the local branch of the Nikkei Sohyo temping agency’s union (seven members) at the end of 2008. He is not interested in politics: he became a union activist because he was about to lose his job and apartment, when Canon decided to terminate temporary contracts ahead of time and refused to pay wages owed for the full duration of those contracts. This abuse turned Mr Kato, an otherwise mild-mannered 35-year-old, into an unyielding activist and something of a local celebrity. With his colleagues he made the eight-hour train ride to Tokyo several times, in desperate attempts to confront Mr Mitarai, first at company headquarters, and then at the shareholders’ meeting. When that didn’t work, they aired their grievances with deputies of the Diet.

They put so much energy into it that in the end, they got what they were owed. “We won our case because of our affiliation with the union. It is based in Tokyo and carries a lot of weight because of its many members, most of whom are salaried employees,” said Mr Kato. “I regret that we couldn’t obtain anything for the others, those who did not join the union. We too were unsure whether to join or not at first, because of the cost of membership and because we feared the consequences.” He added: “Another problem is that many Chinese and Vietnamese are working for Canon for only half our wages. They don’t want to hear about unionism because they fear losing their jobs. Some of them are very young, hired part-time by Canon as foreign interns.”

Mr Kato’s union disbanded in October 2009, within a year of its creation. “Our founding members scattered all over Japan: some went back to their parents’ in other parts of Kyushu, one found a job in Tokyo and joined another union there… It became unmanageable,” he explains. This well illustrates the challenges the new unions face, especially smaller ones, which are often short-lived.

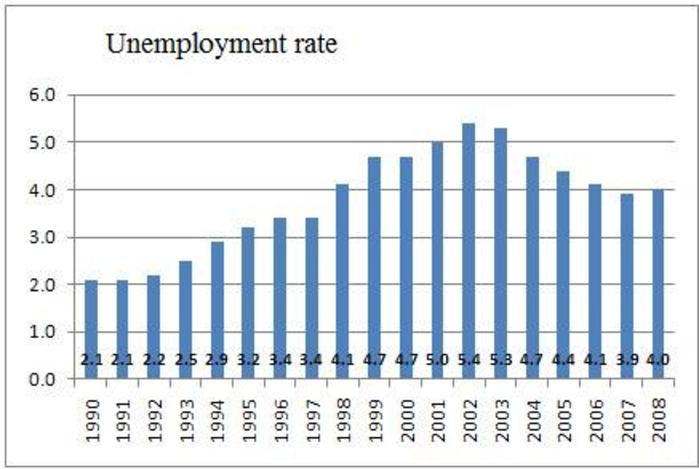

How did the labor situation become so harsh? “Japan underwent brutal reforms with no safety net in place”, sums up Jean-Marie Bouissou, research director at Institut des Sciences Politiques, Paris. In postwar Japan, enjoying a full employment economy, social welfare was provided mostly by companies. But since the economic crisis of the nineties, unemployment has doubled, up from 2% in the early 1990s to 4-5% from the late 1990s forward.

Source: Department of Internal Affairs and Communication, Bureau of labor statistics, Unemployment rate by area, 2009

Graph by David-Antoine Malinas, University of Tohoku.

Temporary work also nearly doubled, rising from 20% in 1990 to 34% in 2008.9 Unemployment benefits from public sources were nonetheless difficult to obtain, and many non-permanent workers could not join the unemployment insurance scheme.

Many of the problems can be traced to 1985, when the Dispatched Manpower Business Act, which legalized temping agencies, was passed to accommodate cost-cutting businesses. Temporary work was first allowed only in a few trades: the method chosen was that of the “open list”, whereby covered jobs were listed. But these provisions didn’t make it through the nineties when Japan’s economic expansion came to a halt and further deregulating reforms were initiated. The 1999 revision of the law during a period of recession introduced the “negative list method”, which specifies exempted jobs. Temporary work thus went from being allowed only in a few trades to being forbidden only in a few trades. The unions’ approval was secured at the time by the inclusion of a restriction on the time period.

Eventually, in 2003, temporary work was allowed in manufacturing industry. The revised law made it possible to keep temps on factory assembly lines for up to three years. The number of industrial accidents among temporary workers dramatically increased in the following years: by 2007, it was 9 times higher than it had been in 2004.10 For other professional workers sent by manpower agencies, including secretaries and interpreters, working on a temporary basis was authorized without specifying the length of service. To top it all, the Unemployment Insurance Law was modified and unemployment benefits were made more difficult to obtain for dispatched workers.

Why did labor unions let that happen? Until very recently, major unions, which are overwhelmingly composed of permanent employees, seemed unconcerned about the plight of precarious employees. Membership in enterprise unions was usually restricted to regular workers, and non-regular workers were for a long time excluded from them. The way the government handled the reforms further explains unions passivity. “The revision of the Dispatching Manpower Business Act is a case in which the Deregulation Subcommittee made policy-making processes contentious,” explains Miura Mari.11 “The major deal between the unions and the government was struck not at the Diet, but at the level of the advisory council. Therefore, the amount of protest raised by Rengo was smaller in scale.”

Looking further back in time, anti-establishment unionism has always been stifled in Japan. Unions weren’t allowed there until 1945, and were then thwarted by the creation of “cooperative” employer-backed company unions.12 Increasing salaries and lifetime employment for core workers further reduced the unions to silence: “In the fifties, Japanese labor unions were very aggressive. But from the sixties onward, job security and better salaries made them cooperative,” explains Suzuki Akira, professor of sociology at the Ohara Institute for Social Research of Hosei university in Tokyo. Public sector employees, who have no right to strike, held their ground until the mid-seventies but eventually gave up as well. “In 1975, they went on strike for eight days for the right to strike, but public opinion did not support them and the government refused to negotiate. Since this defeat, they have become passive, which eased the way towards privatization”, says Mr Suzuki.

As a result, “Japan lacks forums where people can examine and discuss its welfare system”, Mr Kawazoe observes. (Re)building these forums should be the task of the younger generation, as Nishiyama Yuji, Associate Professor of Philosophy at Tokyo Metropolitan University, suggests: “All those doctoral students who find themselves without jobs should create new institutions”.

Emilie Guyonnet is a free lance journalist whose has frequently published in Le Monde Diplomatique. She is the winner of the France-Japan Press Association’s journalism prize.

This article was translated by Ludwig Leibenguth.

Recommended citation: Emilie Guyonnet, Young Japanese Temporary Workers Create Their Own Unions, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 16 No 4, April 18, 2011.

Articles on related themes:

• Yoshio Sugimoto, Class and Work in Cultural Capitalism: Japanese Trends

• David H. Slater, The Making of Japan’s New Working Class: “Freeters” and the Progression From Middle School to the Labor Market

• Toru Shinoda, Which Side Are You On?: Hakenmura and the Working Poor as a Tipping Point in Japanese Labor Politics

• Akagi Tomohiro, War is the Only Solution. A 31-year-old freeter explains the plight and future of Japan’s Marginal Workers

• Kosugi Reiko, Youth Employment in Japan’s Economic Recovery: ‘Freeters’ and ‘NEETs’

Notes

1 Source: Department of health, labor and human services, general survey on trade unions, 2009.

2 The security guards work for a private company hired by the city of Yokohama.

3 Source: David-Antoine Malinas, Young workers labor union and the revival of Japanese labor movement, ICJS Wakai Project Youth Conference: Youth work in contemporary Japan, Temple University, Tokyo, 28 June 2009.

4 See Toru Shinoda, “Which Side Are You On? Hakenmura and the Working Poor as a Tipping Point in Japanese Labor Politics”, Japan Focus, 4 April 2009.

5 “Jichikai” are student self-government associations created after World War II. They were the foundation of the postwar student movement, but in the wake of the campus protests of the late 1960s many campuses disbanded their student self-government associations. Jichikai still exist in some universities.

6 Passed in France in 2006, the CPE stirred mass student protests, leading to its revocation. This labor contract required that employees under the age of 26 undergo a two year probationary period, during the course of which employers could end contracts at any time without any justification.

7 The law of April 1st 2004 turned national public universities into autonomous entities and allowed tuition fees to be raised up to 10% above standard fees set by the state.

8 Source: Highlights from education at a glance 2010, OECD 2010.

9 Source: Department of health and labor, workforce statistics, long term. Quoted by David-Antoine Malinas in “Evolution du travail précaire en France et au Japon”, Japon contemporain, 2nd of December 2008.

10 “5,885 temp workers killed or injured at work in 2007: poll”, Japan Today, 21rst of August 2008.

11 See “The New Politics of Labor: Shifting Veto Points and Representing the Un-organized”, Miura Mari, Institute of Social Science, University of Tokyo, Domestic Politics Project No. 3, July 2001.

12 See The wages of affluence: labor and management in postwar Japan, Andrew Gordon, Harvard University Press, 1998.