Okinawa and Guam: In the Shadow of U.S. and Japanese “Global Defense Posture”

Kensei YOSHIDA

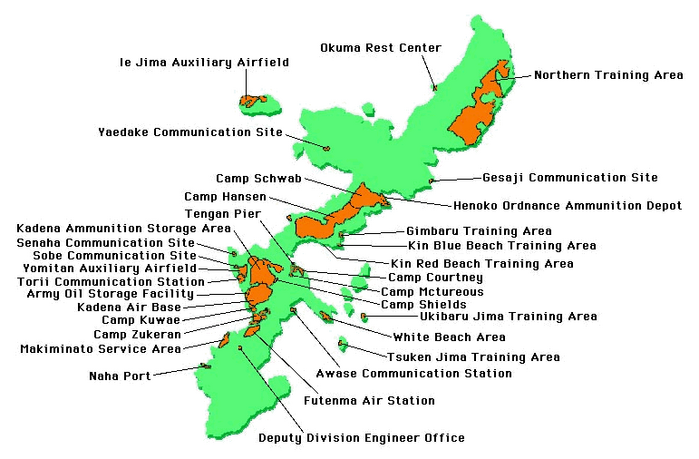

Okinawa is Japan’s southernmost prefecture lying between mainland Japan and Taiwan off China’s east coast. The main island measures twice the size of Guam and has a population roughly seven times greater, or one-third the size of New York’s Long Island with 50,000 more people. On its slender, irregularly shaped island, which constitutes a mere 0.3 per cent of the country、Okinawa hosts 75 per cent in size of all U.S. only military bases in Japan, exclusive of sea and air space. U.S. bases include the Marine Corps jungle training, aviation, bombing and shooting ranges, landing training grounds and an ammunition depot, the largest Air Force base in the region with its own ammunition site, a naval station often visited by nuclear submarines and Army facilities, adding in sum to roughly one-fifth of the densely populated island. It is home to an estimated 24,600 U.S. service personnel, out of a total of 36,000 in all of Japan, many of them living with their dependents in fenced-in “American towns” with schools, gyms, golf courses, shopping centers and churches. Nearly 90 per cent (about 15,000 in number) of the Japan-based Marines are concentrated in Okinawa.

Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, located in the middle of a residential area of the city of Ginowan (population 91,000) north of the capital Naha, reportedly stations 2000 to 4000 personnel of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing of the III Marine Expeditionary Force. Helicopters and fixed/wing aircraft are constantly flying low in circles over the residences, schools and hospitals for embarkation and touch-and-go exercises, creating roaring noise and the danger of crashes. People are so concerned that they have long been demanding its closure and return, with particular urgency since 2004 when one of Futenma’s heavy helicopters spiraled into the wall of the administration building of a university right across the fence and splattered its broken pieces all over during the summer break. In 2006, the Japanese and U.S. governments agreed to relocate many Okinawa-based Marines to Guam by 2014 to lessen the Okinawan people’s burdens or to accommodate “the pressing need to reduce friction on Okinawa.” MCAS Futenma would be returned, but only after being replaced by a new facility that Japan would construct within Okinawa.

Okinawa Prefectural Government, U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa (2004)

The U.S. Department of Defense chose the American territory of Guam for the Marine relocation from Okinawa from geopolitical and strategic perspectives, saying:

“Guam is a key piece of the strategic alignment in the Pacific and is ideally suited to support stability in the region. It is positioned to defend other U.S. territories, the homeland, and economic and political interests in the Pacific region.” [1]

Japan’s Ministry of Defense agreed when it called Guam a “strategic point” located only about three hours away by air and about three days away by sea from principal cities in the Asia-Pacific region [2].

The Department of Defense owns 30 per cent of this 540 square kilometer westernmost territory of the United States, lying between the Pacific Ocean and the Philippine Sea. A deep-water naval station at Apra Harbor with one of the largest ordnance complexes in the world and a four-runway air force base at the northern end with its own ammunition storage area and capacious fuel tanks have made Guam a major military stronghold since the end of World War Two. Andersen Air Force Base was built on the island’s northern plateau in 1944, then served as a B-29 staging point to attack Japan and its Pacific territories and later as a Strategic Air Command (SAC) base during the Korean and Vietnam wars. Thirteen times as large as the MCAS Futenma, it has two air fields with an ammunition site in the middle: one known as Andersen Air Force Base (AFB) at the northeast and another, AFB Northwestern Field (NWF). AFB, with two paved runways, has been used in recent years by B-1 and B-2 stealth bombers, B-52 bombers, F-16 and F-22 fighters deployed on a rotational basis from air bases in the continental United States. NWF also has two runways, but has been virtually untouched for the last sixty years.

The redeployment of “8,000 III Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF) personnel and their approximately 9,000 dependents …from Okinawa to Guam by 2014,” was agreed in May, 2006 between the governments of Japan and the United States as part of their “roadmap for (military force) realignment implementation.” Among the units to move were the III Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF) command element, 3d Marine Division headquarters, 3d Marine Logistics Group (formerly known as Force Service Support Group) headquarters, 1st Marine Air Wing headquarters, and 12th Marine Regiment headquarters. Marine Air-Ground Task Force elements, such as command, ground, aviation, and combat service support, as well as a base support capability would remain in Okinawa.

The 1st Marine Air Wing headquarters and unnamed aviation units at the MCAS Futenma were included in the relocation agenda. “Airfield functions” and “training functions” such as “aviation training,” currently performed at the MCAS Futenma would be carried out in Guam. But this would not be sufficient to enable the closure and return of the MCAS. U.S. officials have insisted that the MCAS Futenma could not be closed until a replacement facility is constructed in Okinawa and the air station is relocated there.

It’s not clear how many U.S. personnel are stationed at Futenma [3], but Mark Thompson of Time magazine reports (June 8, 2010):

“For many in Okinawa, Futenma and its 2,000 American personnel have been a perpetually noisy and polluting symbol of continuing U.S. dominance. But U.S. military leaders insist that as long as the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Force is based on Okinawa, they need the air base, which allows them to rapidly deploy Marines throughout the region. Stalder (Marine Corps Pacific Commander Lt. Gen. Keith Stalder) uses the analogy of a baseball team to explain why the force can’t do without its aircraft: ‘It does not do you any good to have the outfielders practicing in one town, the catcher in another and the third baseman somewhere else’.”

|

MCAS Futenma.

Source: Okinawa Prefectural Government, U.S. Military Issues in Okinawa (2004)

|

But the article leaves several questions unanswered. If the Ⅲ Marine Expeditionary Force needs an air base, why do not they take it with them to Guam, by including the 2,000 troops at Futenma in the 8,000 to 8,600 Marines moving to Guam by 2014 under the 2006 agreement? If the team, outfielders, the catcher and the third baseman, should stay together, shouldn’t the aviation units of the Ⅲ MEF relocate to Guam together with the force command and the 1st Marine Air Wing headquarters? If the team needs to stick together under the field manager and coaches, with the support of dependents, who will stay behind and train at the new Marine Corps air facility to be built in Okinawa against local protests or at other Marine Corps facilities on the island?

Japan agreed to contribute $6.09 billion of “the facilities and infrastructure development costs for the Ⅲ MEF relocation to Guam” while the U.S. would fund the remaining $4.18 billion. Japan’s pledge to cover more than 60 per cent of the total cost was, according to the agreement, to meet “the strong desire of Okinawa residents that such force relocation be realized rapidly.” The realignment was described as a deal to “maintain deterrence and capabilities while reducing burdens of local communities.” The agreement specified that the money allocated was designed for the Marine relocation, but Japan’s contribution is being spent not only to design and build Marine Corps facilities but to subsidize infrastructure improvement at Andersen Air Force base and at a Naval base. [4]

The relocation package was confirmed in the May 2009 Guam Agreement between Japan’s Liberal Democratic administration and the Obama administration and then, on May 28, 2010, in the “Joint Statement of the U.S.-Japan Security Consultative Committee” between Washington and Japan’s new administration under Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama of the Democratic Party. Having set out to put the U.S.-Japan relationship on an “equal footing,” review the realignment roadmap and to relocate the MCAS Futenma out of Okinawa, but unable to find a way out that would be acceptable to the Obama administration, Hatoyama’s government quickly lost its original popularity and he announced his resignation a few days after the joint statement was signed in Washington..

The “Roadmap” was a follow-up to the December, 1996 Japan-U.S. Special Action Committee on Okinawa (SACO) agreement which promised to return “approximately 21 percent of the total space of the US facilities and areas in Okinawa excluding joint use facilities and areas (approx. 40 square kilometers),” including the MCAS Futenma and a large portion of the 50 square kilometer Northern Training Area. The closure/return of each of the facilities/areas was contingent on relocating most of their functions within Okinawa. The MCAS Futenma, for example, would be returned “within the next five to seven years” after a sea-based facility (SBF) was established off the Henoko peninsula near the Marine Corps Camp Schwab training complex on the northeastern coast of the main island of Okinawa. The floating base, connected to land by a pier or causeway, was chosen over two other alternatives—incorporating the heliport into the huge Kadena Air Force Base or building a heliport at Camp Schwab. The heliport, the two governments suggested, would enhance “safety and quality of life for the Okinawan people while maintaining operational capabilities of U.S. forces and could be removed when no longer necessary.”

|

Camp Schwab, Eastward to Henoko Point and Oura Bay. Source: Okinawa Prefectural Government, U.S. Military Issues in Okinawa (2004) |

Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro recalled in June 2005 that his government had tried to convince the other prefectures to accept a replacement facility. Every one of them agreed with the necessity of reducing Okinawa’s burden, he said, but none wanted a U.S. base to be relocated to its backyard and therefore, he said, he had no choice but to settle on Okinawa for the sea-based facility.

The deadline is long past, but no light is seen at the end of the tunnel. Why? The sea-based facility concept soon gave way to a landfill plan and the “roadmap” introduced the idea of Marine relocation of from Okinawa to Guam.

The Futenma Replacement Facility would be constructed with v-shaped runways across the tip of the Henoko Peninsula and in the adjacent sea next to Camp Schwab, an ammunition storage area and a deep-water bay where nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers could be based. The neighborhoods around the MCAS Futenma, located in the middle of a residential area with schools, hospitals, shops and restaurants, have long suffered the disturbance of low-flying helicopter noise and accident danger. In August 2004, an MCAS-based cargo helicopter crashed into the wall of the administration building of a university some 300 meters away from the fence line. It injured no Okinawan but damaged some houses and cars. Many people were shocked and angered not only by the crash but also by the colonial status of their island when U.S. forces cordoned off the off-base site of the crash from local police, government officials and university administrators, and removed the remains of the burned helicopter without permission. The Japanese government did not protest the U.S. invasion into the off-base civilian district and paid compensation for the damage. Futenma citizens and many other Okinawans reinforced their demand that the dangerous Marine Corps base be closed and removed immediately.

Japan was made responsible for conducting a pre-construction environmental assessment of the replacement site (known as a habitat of dugong, an endangered species protected under Japanese and U.S. law), land-filling the waters around the peninsula, building the new facility at its cost by 2014, and then handing it rent-free to the United States for use by the Marine Corps. The Guam relocation was conditional on “1) tangible progress toward completion of the FRF, and 2) Japan’s financial contributions to fund development of required facilities and infrastructure on Guam.”

But local fishermen and other Henoko villagers, environmentalists, and peace activists, supported by many Okinawans outside Henoko and Japanese mainlanders, so fiercely and persistently opposed the intrusion of a new U.S. military base on the island, one-fifth of which is already occupied by U.S. forces, that the Japanese government has not been able to even start the construction 14 years after the SACO agreement and four years after the roadmap agreement.

In April 2009, the Marine realignment to Guam became an international agreement (Agreement Between the Government of the U.S. and the Government of Japan Concerning the Implementation of the Relocation of the III Marine Expeditionary Force Personnel and Their Dependents from Okinawa to Guam) when it was approved in the Lower House of the Diet by the Liberal Democratic Party and the Clean Government Party, although it was rejected in the Upper House where the Democratic Party and the Social Democratic Party held a majority.

The September, 2009 general election further complicated the issue. The Democratic Party, which had campaigned on a platform calling for “equal partnership” with the United States and a review of the Status of Forces Agreement and the contentious U.S. force realignment in Japan, came into power by a landslide victory over the Liberal Democratic Party which had governed Japan for the past half century almost without interruption. Before and after being sworn in as prime minister, party leader Hatoyama Yukio vowed to fight to move the Marine Corps air station out of Okinawa.

A month later, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates visited Tokyo and disputed Hatoyama’s campaign pledge, demanding the new Tokyo government to abide by the 2006 roadmap agreement in view of the vital importance of the Japan-U.S. alliance. Without the relocation of the MCAS by the deadline, he said, there would be no relocation of Marines from Okinawa to Guam and no return of facilities south of Kadena, and that he could not guarantee congressional approval of U.S. funding for the Marine relocation. He was contradicting himself. Gates had visited Guam in May 2008 to look at construction already started in preparation for the Marine relocation from Okinawa and called the military buildup on the island “one of the largest movements of military assets in decades,” which he said would “continue the historic mission of the United States military presence on Guam: serve as the nation’s first line of defense and maintain a robust military presence in a critical part of the world.” [5] “That’s especially critical now,” he added, “in light of the diffuse nature of the threats and challenges facing our nation in the 21st century — a century that will be shaped by the opportunities presented by the developing nations of Asia.” Most Japanese media sided with the U.S. position, calling on Hatoyama to honor the 2006 roadmap agreement in adherence to the Japan-U.S. “(military) alliance” which Hatoyama himself said formed the core of Japan’s foreign policy and the bilateral relationship.

In the meantime, the Marine relocation plan, now combined with U.S. Pacific Command’s “Guam Integrated Military Development Plan” has been making steady progress towards building command, training and housing facilities for the Marines and their dependents, upgrading the Andersen Air Force Base, constructing a deep-water wharf in Apra Harbor for visiting nuclear aircraft carriers and installing an Army missile defense task force. A number of projects are already underway with the money allocated by both governments, cost-sharing ratio unchanged.

Actually, the military expansion in Guam preceded the 2006 realignment agreement. According to the CRS (Congressional Research Service) Report for Congress in January, 2010, “(A)s the Defense Department has faced increased tensions on the Korean peninsula and requirements to fight the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Pacific Command (PACOM), since 2000, has built up air and naval forces on Guam to boost U.S. deterrence and power projection in Asia.” [6]

Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld, who visited Guam in November, 2003, was quoted by a U.S. diplomat in Tokyo as saying repeatedly after the trip, “What about Guam? Let’s build up Guam.” [7] The U.S. had been forced to close its naval base at Subic Bay, the Philippines, in 1992 after the Philippine Senate voted against extending the lease and, at home, Washington was about to kick off the fifth round of base realignment and closure (BRAC), or the first since the cold war ended. According to Rumsfeld, the military, having built up bases since World War Two, had 24 per cent more capacity than it needed.

As Rumsfeld indicated, Guam, home to the Apra (harbor) Naval Base and Andersen Air Force Base, was excluded from the 2005 BRAC list; on the contrary, it was going to be rebuilt into a major forward-deployed outpost under the Pentagon’s “Global Defense Posture” program.

The Defense Policy Review Initiative (DPRI), or the talks between U.S. and Japanese officials that began in 2002 to discuss force realignments in the Pacific, had a particular emphasis on reducing the U.S. presence in Okinawa “that could ameliorate longstanding frustrations among the local population and improve the local political support for the stable and enduring presence of the remaining U.S. forces.” It led to the “Alliance Transformation and Realignment Agreement” (ATARA) in 2005. [8]

In addition to confirming the vitality of Japan-U.S. bilateral defense cooperation and the continued U.S. maintenance of forward-deployed bases in Japan, the two countries approved realignment of U.S. forces in Japan and the Japan Self-Defense forces. The latter was formalized the next year as “the roadmap for realignment implementation.” Two months later, in July 2006, the US. Pacific Command released its “Integrated Military Development Plan.” Subsequently confirmed by the Department of Defense’s “Guam Joint Military Master Plan” of July 2008, the documents envisioned the western-most U.S. territory as a military stronghold with more than 20,000 members of the Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force and Army.

Proposed Military Buildup in Guam (from Joint Guam Program Office, United States Navy, Proposed Action/Guam”)

Why Guam?

In November 2009, the Joint Guam Program Office of the Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Pacific released for 90-day public comment Draft Environmental Impact Statement / Overseas Environmental Impact Statement: Guam and CNMI Military Relocation Relocating Marines from Okinawa, Visiting Aircraft Carrier Berthing, and Army Air and Missile Defense Task Force (Draft EIS). As the title suggests, the 8,000-to-10,000-page document presented potential environmental effects of the proposed Guam military buildup, as required by the National Environmental Policy Act. The buildup would include facilities and infrastructure not only for the Marines relocating from Okinawa but for the nuclear aircraft carriers visiting Guam and for an army missile defense task force to be stationed on the island. Tinian in the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands, too, was surveyed, as Marines are scheduled to conduct shooting exercises there. The strategic and basing plan in the Draft EIS, based on the “Guam Integrated Military Development Plan” and the “Guam Joint Military Master Plan,” had to meet the following requirements:

• “Position U.S. forces to defend the homeland including the U.S. Pacific territories”

• “Location within a timely response range”

• “Maintain regional stability, peace and security”

• “Maintain flexibility to respond to regional threats”

• “Provide powerful U.S. presence in the Pacific region”

• “Increase aircraft carrier presence in the Western Pacific”

• “Defend U.S., Japan, and other allies’ interests”

• “Provide capabilities that enhance global mobility to meet contingencies around the world”

• “Have a strong local command and control structure”

To meet the “pressing need to reduce friction on Okinawa,” the U.S. consulted allies such as Korea, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Australia, but they were all “unwilling to allow permanent basing of U.S. forces on their soil.” “The military’s goal,” the Draft EIS continued,

“is to locate forces where those forces are wanted and welcomed by the host country. Because these countries within the region have indicated their unwillingness and inability to host more U.S. forces on their lands, the U.S. military has shifted its focus to basing on U.S. sovereign soil.”

Guam was “the only location for the realignment of forces” that met “all criteria”—freedom of action, response times to potential areas of conflict and U.S. security interests in the Asia-Pacific region.” It was also considered “ideally” located. Says the Joint Guam Program Office in “Why Guam – guambuildupeis.us”:

“Guam is a key piece of the strategic alignment in the Pacific and is ideally suited to support stability in the region. It is positioned to defend other U.S. territories, the homeland, and economic and political interests in the Pacific region.”

Accordingly, the United States, or the Pentagon, decided to “relocate approximately 8,600 Marines and their 9,000 dependents from Okinawa to Guam,” consisting of the following four “military elements.” [9]

Command element, III Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF), known as Marine Corps’ forward-deployed Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF). The element will involve Headquarters and supporting organizations (Estimated personnel: 3,046);

Ground combat element (GCE), 3rd Marine Division units, which will provide infantry, armor, artillery, reconnaissance, anti-tank and other combat arms (Estimated personnel: 1,100);

Air combat element (ACE), 1st Aircraft Wing and subsidiary units, which operates from sea- and shore-based facilities to support MAGTF’s expeditionary operations (Estimated personnel: 1,856);

Logistics combat element (LCE), 3rd Marine Logistics Group (MLG), which will provide communications, engineering support, motor transport, medical, supply, maintenance, air delivery, and landing support (Estimated personnel: 2,550).

To these will be added transient forces– an infantry battalion (800 people), an artillery battery (150 people), an aviation unit (250 people) and other (800 people) – bringing the total number of Marines in Guam to more than 10,000 personnel.

Guam Functions

In the Draft EIS, the Joint Guam Program Office divides the major functions of the Marines relocating from Okinawa to Guam into the following four:

First, “main cantonment area functions” which “include headquarters and administrative support, bachelor housing, family housing, supply, maintenance, open storage, community support (e.g., retail, education, recreation, medical, day care, etc.), some site-specific training functions, and open space (e.g., parade grounds, open training areas, open green space in communities, etc.), as well as the utilities and infrastructure required to support the cantonment area.”

Second, “training functions” consisting of “firing ranges” for “live and inert munitions practice,” “non-fire maneuver areas” for “vehicle and foot maneuver training, including urban warfare training,” and “aviation training area” to “practice landing/takeoff and air field support (including loading and unloading of fuel, ammunition, cargo and personnel).”

Third, airfield functions for “aviation units and aviation support units” relocating from Okinawa (apparently the MCAS Futenma, the only Marine Corps air station based in Okinawa). The units require runways, hangars and an embarkation facility or the military version of airport terminal for loading and unloading servicemen/women and their weapons to and from aircraft.”

Fourth, waterfront or harbor functions for ”transient” ships and assault craft which, not based in Guam, will visit Guam and the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands from outside for training.

Guam Sites

After the Joint Guam Program Office examined various alternative sites from the perspectives of environmental impacts, political/public concerns and mission compatibility, it proposed the following places as the best candidates for the above functions. They will be formalized in the final EIS expected to come out this summer (2010), officially authorizing the construction projects to start.

Main cantonment function: the Finegayan area on the northwestern coast of the island. Airfield functions (air embarkation and bed down) of the Air Combat Element: the northeastern airfield (which has two improved parallel runways, 11,185 ft and 10,558 ft long) of the Andersen Air Force Base. To quote the Draft EIS:

“Although there are site limitations (i.e., alternative sites in Guam are limited), Andersen AFB met all of the suitability and feasibility criteria (for airfield functions) and is the only reasonable alternative. It is an existing DoD airfield that has sufficient space to accommodate the (fixed and rotary wing) aircraft proposed for relocation from Okinawa.” [10]

Aviation training for the air traffic control detachment and tactical air operations: the Northwest Field (NWF) at Andersen AFB and the north ramp of AFB’s northeastern field.

Aviation training such as formation flights, field carrier landing practice, aerial gunnery, helicopter insertion and extraction (fast rope, rappelling, helo-casting, and parachute operations in improved fields, drop zones, and water operating areas) would be conducted at the NWF and Orote Point Airfield on the southern coast of Apra Harbor as well, and air-to-air and air-to-surface training at “other existing aviation training areas” in the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands and international airspace. New unimproved vertical lift landing zones (LZ‘s) would be developed at Andersen South (former Air Force residential area) and the NMS (Naval Munitions Site).

The proposal identifies the Marine Corps aircraft to be based at Andersen as 12 MV-22 tilt-rotor vertical-takeoff-landing Ospreys, three 3 UH-1 single-engine helicopters, six 6 AH-1 twin-engine attack helicopters and four 4 CH-53E heavy-lift helicopters.

Live-fire training and pistol training would be conducted at the coastal area south of the AFB northeastern field, one of the few sites to be newly acquired by the military, and some on Tinian.

Non-firing maneuver training, including urban warfare training, would take place at Andersen South.

The existing Andersen AFB Munitions Storage Area and the NMS, as well as the existing demolition range at NWF would be used by the Marine Corps for the same purposes.

Inner Apra Harbor would be renewed to accommodate waterfront facilities and operations for amphibious assault landing craft, aircraft carriers, and high speed transport ships.

Guam Budget

To implement the plans, the U.S. Congress authorized about $180 million for Guam’s military construction projects in the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2009 (that became P.L. 110-417 on October 14, 2008). On May 7, 2009, shortly before Japan’s Diet ratified the relocation agreement with the United States, Defense Secretary Gates submitted the proposed defense budget for FY2010, requesting $378 million to start construction in Guam to support the relocation of 8,000 marines from Okinawa, as part of the total U.S. contribution of $4.18 billion tor the relocation. The National Defense Authorization Act for FY2010 authorized roughly $734 million as the first substantial incremental funding for the relocation of Marines from Okinawa to Guam.

In the bill for the FY2011 National Defense Authorization Act, the Obama administration proposed to spend $566 million for military construction projects in Guam and won the approval of the House of Representatives at the end of May, leaving the Senate to discuss it further. The $566 million would include $50 million to Andersen Air Force Base for Guam Strike Group operations and ramp upgrades, combat communications facilities, Red Horse engineering facilities and commando warrior barracks; $426.8 million to the Navy for marine aviation ramp improvements, Apra Harbor improvements and defense access road improvements; and $70 million for the new Naval Hospital and nearly $20 million for the Guam Army National Guard the combined support maintenance ship and the readiness center. [11]

For its part, the Japanese government earmarked 35.3 billion yen or about $390 million in its fiscal 2009 budget for the relocation projects and 47.9 billion yen or about $530 million in 2010. Japan is committed to use its funds to develop infrastructure at Finegayan, the north area of Andersen AFB and Apra Harbor, design and build a fire station, bachelor enlisted quarters at Finegayan and port operation unit headquarters building and medical clinic at Apra Harbor, and design and build the MEF command and headquarters buildings, a military police station, a gymnasium and a restaurant all at Finegayan. [12]

Guam Opinions

How has Guam reacted to the Marine realignment and the ensuing military buildup?

With the island mired in a deep slump in the 1990s and the 2000s as a result of sluggish tourism and the post-cold war closure of a number of bases, Guam’s political and economic leaders had been calling on Washington to send back the military. To Governor Felix P. Camacho, with many businesses idle and workers out of jobs, the Marine relocation was a dream come true. In his “2008 State of the Island Address,” Camacho enthusiastically welcomed the Marine relocation to the island:

“In a few short years, this island as we know it, will be transformed by the work we do today. The Guam Buildup, as I like to call it, has generated much excitement and confidence in the future. The accompanying investments, construction and population growth will present tremendous opportunity for new and better jobs, higher wages and an improved quality of life for the citizens of Guam. We have only one opportunity to get it right. In this upcoming period of significant growth, we must not squander this precious opportunity. Our stewardship of the resources entrusted to us will determine the inheritance we leave future generations.”

The Governor repeated the message in October 2009 by stating:

“We are at the beginning of a period of tremendous opportunity. The growth in jobs, income, and the long term improvement of our roads, utilities and community facilities, which the military build up will bring, is unprecedented. There has never been, in my life time, a greater opportunity to improve the quality of life for all Guamanians.” [13]

The enthusiasm, however, was not unqualified, nor was it shared by all Guamanians. The Governor, Madeleine Z. Bordallo、non-voting delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives, and other leaders, while supporting the military build up, kept calling for infrastructure improvements outside the fence, and expressing environmental concerns such as possible damage to the coral reef.

A reader of the Pacific Daily News probably summed up the sentiment of many Guamanians opposed to the build-up, particularly native Chamorro people, when he wrote: “I think we all may have second thoughts about the military transfer but we don’t count. They will do whatever they feel they must do to enhance National security. We must accept that fact. We can grouse all we want and pitch a fit but no one in Washington, DC will hear or care.” Guam is an “unincorporated territory” of the United States inhabited by American citizens without the full application of the U.S. constitution. Without voting rights in the Presidential and Congressional elections, they have little means of getting their voices heard or reflected in national politics.

People of Chamorro ancestry in Guam, estimated to number between 60,000 and 70,000 (about one-third of the population), are concerned about losing their identity and culture in the face of a sudden increase of military personnel, off-island construction workers and their dependents.

Conclusion

Prime Minister Hatoyama’s attempts, like Koizumi’s, to relocate the MCAS Futenma out of Okinawa failed. On Okinawa, discontent with the status quo was heating up. In the 2009 general election, people elected only those candidates who were committed to opposing construction of the replacement facility within Okinawa. Earlier this year, citizens of Nago, where Henoko is located, voted for a new mayor opposed to the construction, and the Prefectural Assembly adopted a unanimous resolution across party lines to demand the closure and return of the MCAS Futenma. On April 25, a huge rally attended by Governor Nakaima, the president and all members of the Prefectural Assembly, mayors and an estimated 90,000 people from all over the prefecture, most of them wearing yellow shirts or head-band or holding yellow placards to show their opposition to the realignment roadmap, called for removal of the MCAS from Okinawa. Opinion polls suggested an overwhelming majority of Okinawan people wanted the MCAS Futenma moved away and not replaced by a new air facility on their island.

Hatoyama’s appeal at the National Governors’ Conference at the end of May, however, only confirmed the results of the surveys conducted earlier by Kyodo News and the Asahi Shimbun: all other prefectures showed “unwillingness” and “inability” to accommodate a U.S. military base relocated from Okinawa. The entire nation, while mostly supporting the military alliance with the United States, was strongly opposed to accommodating U.S. troops or an aviation training facility in their own localities, as Koizumi had discovered in 1995. The Hatoyama administration ultimately settled for the Henoko coast, respecting the voice of the mainland Japanese but disregarding that of the Japanese on Okinawa.

While the Marine relocation and other military buildup projects in Guam are making progress for the targeted completion by 2014 in the way of financial contributions, construction contracts and building of housing complexes for off-island workers and their dependents, the following questions remain.

1. Why doesn’t the United States respect the democratically expressed voice of the overwhelming majority of Okinawan people who want U.S. military bases closed and removed together with their hazards, and why doesn’t it follow its principle of locating forces only where those forces are “wanted and welcomed”?

2. How many Marines will stay behind in Okinawa after 8,000 (in the realignment agreement) or 8,600 (in the Draft EIS) move to Guam, and what units will use the replacement air station to be built off the Henoko coast in northeastern Okinawa?

3. Does the United States need to keep the MCAS Futenma, located in the middle of a populated residential area, over the local protests and concerns about noise and possible accidents such as crashes, until the completion of the replacement? Why cannot not the Marine Corps aviation units train at the Kadena Air Base as they did while the MCAS Futenma was being renovated several months ago, at the spacious Air Force Base in Guam, or at a sea base made up of an aircraft carrier and its support vessels?

4. Why does the U.S. need to station so many Marines in Japan (15,000 in Okinawa alone), way above the estimated 5,500 in Hawaii 20 in Alaska, 300 in Germany, 150 in Spain, 90 in U.K., about 130 each in South Korea and Djibouti? Why does it need to keep so many Marine Corps training sites, as well as the huge Kadena Air Base, a naval station often visited by nuclear submarines, etc., in this crowded Japanese island? Why not relocate them all to the United States, where many “excess” military installations have been closed over the last three decades, often against the protests of local politicians, businessmen, war veterans, military workers and members of other interest groups?

Okinawa’s Share of U.S. Forces Stationed in Japan

* U.S. Department of Defense, “Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country, June 30, 2010”

** Figures, as of the end of September 2009, taken from the statistical booklet on military bases in Okinawa published by the Okinawa Prefectural Government in March 2010.

Ministry of Defense

*There is no U.S.-only base in the remaining 34 prefectures.

5. Why are the U.S. military bases in Japan concentrated in the tiny island far away from Tokyo, the country’s political, economic, academic, communication and cultural center with one-tenth of the whole population? For the same “geopolitical reasons” that the U.S. used during the cold war, the Vietnam War, the Korean War and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and in recent years, for the nuclear threats of North Korea and China’s rising military power to the United States? Is the U.S. going to keep its military “footprint” in Okinawa, a prefecture of Japan, as long as what it considers that “threats” exist in the region or elsewhere in the world, or so long as Japan leaves the bases and personnel under the control of the United States and is willing to fund them so generously (providing three-quarters of the total cost?

Kensei Yoshida [Yoshida Kensei] is a native of Okinawa who now lives in Naha after retiring in 2006 from Obirin University in Tokyo where he taught Canadian history and society, Canadian politics and foreign relations, U.S. politics, modern Okinawan history, and journalism. Author of Democracy Betrayed: Okinawa under U.S. Occupation (2002), Kanada-wa Naze Iraq-Sensou-ni Sansen Shinakattanoka (Why did Canada Not Participate in the Iraq War) (2005), Senso-wa Peten-da (War Is A Racket: the Status of Forces Agreement in the Eyes of General Butler) (2005)、and Gunji Shokuminchi Okinawa (Okinawa: A Military Colony) (2007). Earlier this year, he published Beigun-no Guam Togo Keikaku: Okinawa-no Kaiheitai-wa Guam-e Iku (Guam Integrated Military Development Plan: U.S. Marines Are Relocating to Guam) from Kobunken Press in Tokyo.

Recommended citation: Kensei Yoshida, “Okinawa and Guam: In the Shadow of U.S. and Japanese ‘Global Defense Posture,'” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 26-2-10, June 28, 2010.

Notes

[1] Joint Guam Program Office, “Why Guam – guambuildupeis.u0073”

[2] Ministry of Defense website on the Guam relocation.

[3] According to the Marine Corps Camp S.D. Butler, Newcomers’ Information Booklet posted in 2007, the Air Station is “home to approximately 3,000 Marines and Sailors. It is capable of supporting most aircraft and serves as the base for Marine Aircraft.”.

[4] Ministry of Defense, cit.

[5] American Forces Press Service, “Gates Views Massive Growth Under Way in Guam,” May 30, 2008.

[6] Shirley A. Kan and Larry A. Niksch, “Guam: U.S. Defense Deployments,” Congressional Research Service, CRS Report for Congress, May 22, 2009.

[7] James Brooke, “Looking for Friendly Overseas Base, Pentagon Finds It Already Has One,” New York Times, April 7, 2004.

[8] Joint Guam Program Office, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Pacific, Draft Environmental Impact Statement /Overseas Environmental Impact Statement Guam and CNMI Military Relocation Relocating Marines from Okinawa, Visiting Aircraft Carrier Berthing, and Army Air and Missile Defense Task Force(Draft EIS), Volume 1: Overview of Proposed Actions and Alternative, pp. 1-18.

[9] Draft EIS, Volume 2, Marine Corps relocation: Guam, 2-1.

[10] Op.cit., 2-76.

[11] Mar-Vic Cagurangan, Marianas Variety News, “Guam gets $566M under ‘11 DoD budget”(May 21, 2010)

[12] Ministry of Defense, cit.

[13] Office of the Governor of Guam, ”Governor Unveils Guam’s Vision to Address Military Buildup” (Oct. 11, 2009).

See the following articles on Okinawan and Guam bases and anti-base movements:

Gavan McCormack, Ampo’s Troubled 50th: Hatoyama’s Abortive Rebellion, Okinawa’s Mounting Resistance and the US-Japan Relationship

Furutachi Ichiro (video) and Norimatsu Satoko (text), US Marine Training on Okinawa and Its Global Mission: a Birds-Eye View of Bases From the Air

LisaLinda Natividad and Gwyn Kirk, Fortress Guam: Resistance to US Military Mega-Buildup

Yoshio SHIMOJI, The Futenma Base and the U.S.-Japan Controversy: an Okinawan perspective

Kageyama Asako and Philip Seaton, Marines Go Home: Anti-Base Activism in Okinawa, Japan and Korea