Hillary in Japan – The Enforcer

Gavan McCormack

Crumbling Kingdom

Debilitated by nearly 20 years of rising debt levels, stagnation, mismanagement and lack of direction, Japan faces an economic crisis of almost unprecedented severity. Considerably worse than the US (and worst in the post-war period, according to Economic and Fiscal Policy Minister Yosano Kaoru), it is matched by a no less severe political crisis. Even before Finance Minister, Nakagawa Shoichi, gave the incoherent, alcohol-driven performance at the Rome G7 Finance Ministers’ meeting that cost him his job, the Aso government’s support level in the polls was down to 14 per cent [1]. Since then it has obviously fallen further, by some accounts already to around the nine percent record low of Prime Minister Mori Yoshiro in 2001.

The Diet is one whose Lower House was elected in September 2005, when Prime Minister Koizumi’s popularity was at its height and he swept all opposition before him to secure a two-thirds majority on the simple question of “reform” – by which he meant yes to postal privatization (as central to a broad neo-conservative economic agenda). The following year, however, he passed the baton to Abe Shinzo, whose neoconservative political agenda soon saw support plummeting, causing him to lose control of the Upper House in elections in 2007. Abe too then resigned, handing over to Fukuda Takeo, who also in turn, after an ineffectual term in which political initiatives were largely frozen by the split parliament, resigned, making way, in September 2008, for the present incumbent, Aso Taro. The only reason that Abe, Fukuda, and now Aso could form governments was because of the Lower House majority won by Koizumi in 2005. It is that “postal privatization” House of Representatives which now, public support plummeting, is to be called on to ratify a major political and strategic agreement between the US and Japan.

Prime Minister follows Prime Minister while consultation with the electorate is postponed as long as possible in the hope that the LDP will somehow be able once again to find electoral favour. When Aso was given the job in September 2008, he was popular and it was assumed that he would quickly go to the polls to exploit his popularity. Instead, he postponed it (in the hope of improving his party’s chances), and the more he did so, the more his government’s fortunes fell, and the more the country slid into financial and economic crisis. Aso’s recent attempt to position himself for an election by buying off a disgruntled electorate with a two trillion yen stimulus package that includes a handout of 12,000 yen (ca $200) to each household back-fired as it was widely seen as a cheap ploy irrelevant to the country’s deep-seated economic, financial, and budgetary problems.

The LDP’s stock has been further lowered in the public eye recently as both Nakagawa and Prime Minister Aso have shown themselves to be unable to read prepared texts without mistake (Aso has boasted that he only reads manga comics), or to answer correctly simple questions and (in the case of Aso) appearing to shift position in accord with the political winds. The Yomiuri shimbun (18 February) quoted the well-known novelist Takamura Kaoru, “Japanese politics is on the verge of collapse.” Few would disagree.

The Clinton-Nakasone Deal: Okinawa under the Revamped Alliance

It was to the capital of this crumbling kingdom that Hillary Clinton flew in on 16 February, on her first mission as Secretary of State of the new Obama administration. The following day, she and Japanese Foreign Minister Nakasone Hirofumi (son of former Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro – as in 18th century England, most Japanese political leaders have inherited their positions, and are second, third, or fourth generation politicians of what in England used to be called “rotten” or “pocket” boroughs) signed an Agreement, nominally on the transfer of Marines from Okinawa to Guam.

Clinton and Nakasone

was in the form of a package, and the package contained much more than a transfer of Marines to Guam: the US marine base at Futenma would be transferred to Henoko in Nago City in Northern Okinawa (to a new base to be built by Japan), the US military in Okinawa would be concentrated in the north of the island, vacating its bases in the south to take up its new ones in the north, and 8,000 Marines would be relocated from Okinawa to Guam, with the Japanese government and taxpayers paying $6.09 billion towards the transfer cost (of which $2.8 billion was to be in cash in the current financial year). The US promised not to use Japanese funds for purposes other than those stipulated.

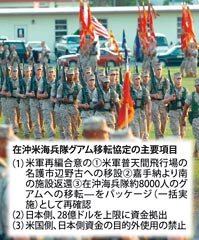

Ryukyu shimpo(16 February 2009) reports the February Deal, under the heading “Guam Relocation Agreement in reality promotes “Reorganization of US Forces in Japan”

It was an astonishing agreement. First, because its core matters had all been resolved by a previous agreement, nearly four years earlier – the October 2005 agreement on “US-Japan Alliance: Transformation and Realignment for the Future” reconfirmed by the May 2006 “United States-Japan Roadmap for realignment Implementation.” [3] All that the new Agreement did was to take the major sections of the 2005-6 “Roadmap” agreements on which there had been little or no progress (in particular on the new base Japan had promised) and reiterate them. Article 3 of the new Agreement declares that “The Government of Japan intends to complete the Futenma replacement facility as stipulated in the Roadmap [i.e. by 2014] precisely because the parties had virtually abandoned hope that that was possible. Admiral Timothy Keating, head of US Pacific Command, told a New York press conference in November 2008 that he did not expect the Roadmap target of 2014, “or may be even 2015,” to be met. [4] The political commitment of 2006 was now to be raised in status to a formal diplomatic accord, in effect, a treaty (though, as such, it must first be ratified).

37 years after Okinawa’s “reversion” from the US to Japan in 1972, most major US bases remain intact, taking up one-fifth of the land surface of Okinawa’s main island. The heaviest US footprint is that of the US Marine Corps Futenma Air Station, which sits astride the densely populated city of Ginowan. The US and Japanese agreed in 1996 that it would be returned, but made return conditional on construction of a replacement facility, which would also have to be in Okinawa, and not just anywhere in Okinawa but in the lightly populated but environmentally sensitive north, the coral and forest environment of Henoko, in Nago City. A peace and environment citizens’ coalition from 1996 to 2005 fought the first version of that plan – for an offshore, pontoon-supported structure on the reef just offshore from Henoko – to such effect that it was abandoned The second, and current, version was adopted in 2006. It was for an onshore site in the same Henoko district, to be built on land and landfill extending from the existing Camp Schwab US base into Oura bay. The “Futenma Replacement Facility,” as by now it was known, had grown from a modest “helipad,” as it was referred to in 1996, to a removable, offshore pontoon with a runway, initially 1,500 meters but gradually stretching to 2,500 meters, between 1999 and 2006, to assume its current form of dual 1,800 meter runways stretching out from Cape Henoko into Oura Bay, plus a deep sea naval port and other facilities, and a chain of helipads scattered through the forest – a comprehensive air, land and sea base able to project force throughout Asia. Each time the project was blocked by popular opposition, it came back significantly bigger. Today, even the (conservative) Governor rejects the existing design, although his call for the construction to be shifted again slightly offshore may be more temporizing than principled, and virtually all the prefecture’s 1.3 million people, as well as the majority in the Okinawan parliament, the Prefectural Assembly (elected in 2008), are opposed. [5]

US irritation at the lack of progress since the signing of the May 2006 Agreement has risen steadily. Richard Lawless, who as Deputy Defense Secretary had headed the negotiations that culminated in the 2006 Roadmap, told the Asahi in May 2008 [6]:

“It appears that a good deal of the focus on our alliance transformation that did exist under the Koizumi and Abe governments does not exist under this government. What we really need is a top-down leadership that says, “Let’s rededicate ourselves to completing all of these agreements on time; let’s make sure that the budgeting of the money is a national priority….

Japan clearly is not making adjustments and developing the alliance in its own best interest. Somehow it has to find a way to change its own tempo of decision-making, deployment, integration and operationalizing [sic] this alliance. Otherwise, Japan becomes marginalized and the alliance becomes increasingly marginalized.

Again, weeks ago, Lawless castigated Japan for its “self-marginalization” and for “allowing the alliance to degenerate towards sub-prime because of its withdrawal syndrome.” [7]

Like Richard Armitage, Lawless sees Japan it as a satrapy that needs guidance and direction in the service of an expansive security role under US direction (on Armitage, see my Client State, passim). Despite the overweening contempt they display for Japan, Lawless and Armitage continue to be treated with deference in Japan. The February 2009 Agreement may be seen as the Japanese response to the American demand that construction on the base proceed without further delay, and to that end that “top-down” steps be taken. “Operationalizing” the alliance required it.

With confidence in Aso plummeting, the Obama administration had good reason to treat the matter as urgent. Before Aso’s government collapsed, and while the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) still enjoyed the Koizumi majority in the Lower House, the 2005-6 deal had to be consolidated and Japan had to promise to enforce it. With Nakasone’s signature on the Tokyo document, it still has to be ratified by the Diet. That debate is expected to occur during March, and ratification may turn out to be one of the last Aso government acts before election. So long as the Koizumi parliamentary majority lasts (and provided the LDP does not split or fall apart in the meantime), that ratification should be possible. Once that is done, the US will insist it be honoured, whatever future government Japan might have. As Hillary put it, “I think that a responsible nation follows the agreements that have been entered into, and the agreement that I signed today with Foreign Minister Nakasone is one between our two nations, regardless of who’s in power.” [8]

It was a clear shot across the bows of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) and its increasingly popular leader, Ozawa Ichiro. The US knows full well the DPJ’s position that no new base should be built within Okinawa, i.e. that Futenma should be returned tout court. [9]

Washington has made clear that it views Ozawa with nervousness and distrust. Hillary’s mission, therefore, has to be seen as a means to block his party from implementing its Okinawa policy. The gauntlet now thrown in his face, Ozawa must decide whether or not to resist ratification. If he chooses to resist, an unprecedented diplomatic crisis will erupt.

During the long, perhaps soon to end, era of LDP hegemony, Washington could dictate Japanese foreign and defense policy. Defense Secretary Gates on his November 2007 visit instructed Japan it should resume its Indian Ocean naval station (then hotly debated), maintain and increase its payments for hosting US bases, increase its defense budget, and pass a permanent law to authorize overseas dispatch of the SDF whenever the need arises. Like Richard Armitage earlier, demanding Japanese “boots on the ground” in Iraq and billions of dollars for Iraq “reconstruction”, or Richard Lawless later, insisting on “top-down” resolution of the Okinawa problem, US officials always add the sentiment that of course everything is up to the sovereign government of Japan. Only on rare occasions do they spell out the consequences of non-compliance. One such occasion was when Secretary Gates bluntly told Japan that it could not hope to receive US support in its bid for a permanent seat on the Security Council unless it pursued the agenda he had set out.[10] As for DPJ leader Ozawa, when he briefly adumbrated a shift in Japanese foreign and defense policy from a Washington centre to a UN-centre, ending its deployment of the Maritime Self Defense Forces to the Indian Ocean in service to the US-led war effort in Iraq (then hotly debated), Ambassador Schieffer, who till then had refused to meet him, suddenly demanded a meeting, plainly to lay down the law, and prominent US scholar bureaucrats joined in issuing thinly veiled threats about the “damage” that Ozawa was causing to the alliance.[11]

The Obama government seemed set to be even less tolerant of Japan’s procrastinations, and less sympathetic to the agonized fumbling in search of an independent, regional or UN-centred foreign policy than its predecessor. It was demanding that Aso (or his successor) crush Okinawa’s opposition. For all her mild demeanour, therefore, and her messages of humility and renewal, Hillary went to Tokyo as enforcer.

The second reason for astonishment is that the global media would report the relocation (“troop withdrawal”) agreement as if it were a major US concession to Japan, and especially to Okinawa. Actually the deal was a further step in implementation of Donald Rumsfeld’s so-called “Revolution in Military Affairs” doctrine whose intent was to increase the Japanese burden or “contribution” to the alliance. Japan would pay an enormous price for the despatch of 8,000 Marines to Guam. Presented by the global media as a design “to reduce the burden of post-World War ll American military presence in Okinawa,” [12] it was actually nothing of the kind. Subtraction of 8,000 Marines would still leave around 15,000, and a new high-tech military base complex would be built for them. In addition, Japan was also committing itself to build another fabulously expensive base complex in Guam, and it was taking steps to integrate Japanese forces henceforth under US intelligence and command (for details: Client State, passim). Okinawa in particular was marked for militarization and US dominance. The Agreement spelled greater, not lesser military presence, even as it reduced the number of GIs stationed in Okinawa. It amounted to one more in the sequence of shobun (disposals) that have marked Okinawa’s tragic experience within the Japanese state ever since the islands were first conquered by Japanese samurai in 1609, just 400 years ago.

Japan must now take all necessary steps, “top-down,” to build the Henoko base without further delay. Both governments were saying, implicitly, that they would ignore the proceedings in the San Francisco court against the Pentagon over precisely this base construction plan (For details, see Yoshikawa Hideki’s analysis in The Asia-Pacific Journal), and the probable illegality under Japan’s domestic law of its environmental assessment procedures. The Bush-Cheney-Rumsfeld agenda becomes now the Obama-Clinton agenda and the February Agreement can only be seen as a virtual declaration of war against Okinawa’s civil society and its Prefectural Assembly. So much for those in Okinawa who hoped that Obama’s administration might actually mean “change”.

In short, the basic problem about the 2005-2006 Agreement was that it was done without consultation, over the heads and contrary to the wishes of Okinawans (for that matter it was done also without significant public or political debate in Japan as a whole). The 2009 Agreement now reproduces and intensifies those very faults. Public opinion then was overwhelmingly hostile and even the Governor was outraged. The Okinawan movement had blocked all plans for construction of the base at Henoko (in its previous form, offshore) for nearly 10 years between 1996 and 2005, and ever since then has continued to block attempts to survey and commence construction at Henoko and in the adjacent forest (where a series of helipads are planned). The Government of Japan, having tried unsuccessfully by every means to weaken, split, buy off and intimidate those opposed to the construction of any new base in the near pristine environment of Northern Okinawa, now is committing itself to take determined “top-down” steps to crush the Okinawan resistance. Even before the Clinton visit, the government had begun legal action to evict protesters against the Helipad construction from Takae in the Yambaru forest. The two super states now combine to root out and crush the Okinawan resistance.

Japan as “Reverse-Mercenary” State

Japan would pay dearly for its submission. Apart from the $6 billion cost for the construction of US military facilities in Guam (“relocation costs”) – for which surely there is no precedent elsewhere – it is estimated that the Henoko base construction will cost around one trillion yen (some $11 billion), and the missile defense system to which Japan had committed itself and which its Ministry of Defense estimates will cost between $7.4 and $8.9 billion through 2012 [13], and undoubtedly Clnton’s February mission would put pressure on Japan (likewise Korea and Indonesia) to step up purchases of other military hardware. In addition, Japan would be expected at very least not to attempt any reduction in the military tax it has been paying the US government for the past 30 years, known in Japan as “Omoiyari” (Consideration or Sympathy) and in the US as “Host Nation Support” (roughly 200 billion yen, currently $2.2 billion per year). The structure of this military tax system dates to the reversion of Okinawa from US to Japan in 1972, which was actually a purchase, Japan paying the US more for the return of its islands than it paid South Korea in 1965 and since as compensation for half a century of colonial rule.

Japan can also always be relied on to pour in funds as demanded to support US causes, such that it is said that President George W. Bush once jokingly referred to Japan as an ATM machine which required no pin number. It remains to be seen whether Japan’s economic, financial, and increasingly social, crisis will dent this reliability

There is good reason to think, counter intuitively, that it was the Government of Japan, not the Pentagon, that insisted on the Futenma replacement Facility being built in Okinawa, and that then insisted on paying all necessary costs both for that and for the partial transfer to Guam. The Pentagon seems to have been flexible and open to other possible arrangements, but the Japanese offer was simply too good to refuse. [14]

The Clinton-Nakasone agreement, which undoubtedly furthered the integration of Japan and the US, and specifically of Japan’s military (Self-Defense Forces) with the US military, was Japan’s choice. Japan’s leaders preferred to wrap themselves ever more tightly within the US embrace rather than consider seriously any possible turn towards positive engagement in the construction of an Asian “community.” The Japanese state becomes a “mercenary in reverse”, one that pays to subject itself. To explain such a peculiar state formation and its accompanying psychology, I have suggested thinking of Japan as America’s “Client State,” i.e. a state that enjoys the formal trappings of Westphalian sovereignty and independence, and is therefore neither a colony nor a puppet state, but which has internalised the requirement to give preference to ‘other’ interests over its own.

Hillary Clinton invited Aso to Washington to meet the president on 24 February. When Aso makes that visit, he will be conscious of the words spoken in Munich weeks ago by the new Vice-President, Joseph Biden: “America will do more, but America will ask for more from our partners.” Aso will undoubtedly try to find more ways to channel Japanese monies to Washington and other ways to help the US expand its war in Afghanistan. In return, he will seek what Japanese leaders have always sought from Washington – help in shoring up a crumbling government and reversing the tide that now runs so strongly against it.

The pathetic showing of Finance Minister Nakagawa in Rome is matched by the pathetic showing of Foreign Minster Nakasone and Prime Minister Aso in Tokyo. For the one, there might at least have been the excuse of exhaustion and drink, but for the other, none at all. Humiliation and submission in Tokyo is structurally determined, the fruit of long US design to construct Japan as a “Client State.”

Okinawan View of the Agreement

Okinawan voices are rarely heard in Tokyo, Washington, or indeed anywhere outside of Okinawa. I therefore reproduce below the “Open Letter” addressed by 14 representative figures of Okinawa’s civil society to secretary of state Clinton on the occasion of her Japan visit:

|

February 14, 2009

Hillary R. Clinton, Secretary of State. Dear Madame Secretary, The people of Okinawa have never welcomed the continuous presence of United States military bases since the end of the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. We have been deprived of opportunities to express our own will regarding the bases. In his famous Fourteen Points speech, President Woodrow Wilson stated that “a free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be determined.” Yet even today the people of Okinawa do not fully own the right of self-determination which President Wilson saw as an essential condition for world peace. The very origins of the military base issue in Okinawa lie in the lack of this right of self-determination No matter how many times or how strongly the President and Congress would express their gratitude to Okinawa people for the hardships of letting US military bases operate in Okinawa, their words have never reached the Okinawa people’s hearts. Please imagine what we have experienced and try to understand why we would not accept your words of gratitude. For example, most of the US military bases were built on land that was forcefully taken away. SOFA is another cause of anger because SOFA severely limits Japanese judicial authority over crimes committed by US soldiers, even serious crimes like rape. And consider astonishingly beautiful coral reefs that would be destroyed to construct your new base in Henoko. The US government has refused to take any responsibility by claiming that the new base construction is solely under Japanese jurisdiction. Another example: USMC Futenma does not meet the US operational safety standards for Navy and Marines airfield. Local residents are exposed to high risk flights and noise pollution, experiencing constant fear, while aircrafts fly over residential areas late at night and early in the morning. Okinawa, a small island, has lived under such great stress for over sixty years. The presence of US military bases has distorted not only the politics and economy of Okinawa, but also its society itself and people’s minds and pride. Do you think we would accept your gratitude in exchange for accepting these ongoing hardships? We do not need to remind you that Okinawa is not your territory. Your fifty thousand military members act freely as if this is their land, but, of course, it is not. Please remember that we, the Okinawa people, own “the inherent dignity” and “the equal and inalienable rights of all the members of the human family,” which is stated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, just like your family and friends do. These equal and inalienable rights are not respected in Okinawa. The governments of the United States and Japan legitimized the US military occupation of Okinawa with the San Francisco Treaty in 1952, and the reversion of administrative rights in 1972 created a structure of economic and financial dependency in exchange for the presence of US military bases on Okinawa. The governments have changed their strategy for maintaining the base presence from using force to using money. This is a very cruel treatment. The people of Okinawa have increased dependency on such money. The money has created a system which has corrupted our minds. It has taken away alternatives. The acceptance of US bases is seen as the only way to live. Furthermore, US military bases in Japan are highly concentrated in Okinawa and this condition clearly shows discrimination. This is an absurd situation, isn’t it? It is as if the Japanese government has made Okinawa a drug addict and the US government takes full advantage of the addiction, in order to maintain its military presence. Violations of human rights and the destruction of coral reefs, a treasure of human kind, are taking place in Okinawa, despite the fact that it is a part of Japan which is a highly industrialized democracy. “The world order” based on the American values and the “security of Japan” depend on the structure that deprives the Okinawa people of the “inherent dignity”. Those who are concerned with world peace should pay attention to this structure. Okinawa’s situation is one of the cracks of the world community that should be mended. Maybe Okinawa’s problems are small ones among the entire challenges that mankind is facing today. But it is a big issue for the people involved. When you have military bases on a foreign soil that does not accept and support them, you constantly need to be worried about the long term stability of the bases, and the potential crisis continues. This is a burden not only for Okinawa but for the US as well. In 2005 and 2006, the governments of the United States and Japan reached agreements regarding the reorganization of US military bases in Japan. They agreed on the construction of new bases and it seems that they are trying to make the US military presence in Okinawa permanent. This plan would add a further burden on the people of Okinawa who have suffered long enough. In other words, something that other parts of Japan refused to accept would be dumped on Okinawa again. Most of us are opposed to the executive agreement that you would sign during your stay in Japan. Here we state our tenets:

Please look into Okinawa’s situation from the standpoints of democracy, human rights, and environmental concerns during your visit to Japan. We hope that you will take new initiatives in U.S. policy toward Okinawa during the Obama administration President Obama states he would learn from Japan’s experience of “the lost decade of the 1990s” in his efforts to revive the US economy. The Okinawa people wish for you and President Obama to bring about the end of “the lost sixty-four years” forced on us by the US military bases. Seigen Miyasato, Chairperson, Okinawa Foreign Policy Study Group, Naha, Okinawa, Japan.

And the following: Arakawa Akira, Journalist; Arasaki Moriteru, Emeritus professor, Okinawa University, Oshiro Tatsuhiro, Novelist, Gabe Masaaki, Professor, Ryukyu University, Sakurai Kunitoshi, President, Okinawa University, Sato Manabu, Professor, Okinawa International University, Shimabukuro Jun, Professor, Ryukyu University, Higa Mikio, Political scientist, Hoshino Eiichi, Professor, Ryukyu University, Teruya Hiroyuki, Professor, Okinawa International University, Miki Takeshi (Ken), Journalist, Miyazato Akiya, Journalist, Yui Akiko, Journalist

|

Notes:

[1]

Japanese version

English version

[2] Asahi shimbun, 11 February, 2009 (disapproval: 73 per cent),

[3] For details, see my Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, New York and London, Verso, 2007, chapters 5 and 7.

[4] “Obama and Japan – Futenma relocation a pressing issue,” Yomiuri Shimbun, 20 November 2008.

[5] For details on these developments, see the various articles posted on Japan Focus, including those by this author.

[6] Yoichi Kato, “Interview/ Richard Lawless: Japan-U.S. alliance faces ‘priority gap,” Asahi shimbun, 2 May 2008.

[7] Quoted by Funabashi Yoichi, “Obama seiken to Nichibei kankei – Heiji no domei tsuikyu suru toki,” Asahi shimbun, 26 January 2009.

[8] “Clinton praises strong U.S.-Japan Ties,” Yomiuri shimbun, 18 February 2009.

[9] There is, however, some room for doubt as to whether the DPJ’s opposition is strategic and absolute or tactical and focussed on details sch as cost. “DPJ should back US marine move plan,” Yomiuri shimbun, 21 February 2009.

[10] Kaho Shimizu, “Greater security role is in Japan’s interest: Gates,” Japan Times, 10 November 2007.

[11] Kurt Campbell and Michael Green, “Ozawa’s bravado may damage Japan for years,” Asahi shimbun, 29 August 2007.

[12] AFP, “Clinton, Japan sign US troops pull-out deal,” Sydney Morning Herald, 18 February 2009.

[13] Masako Toki, “Missile defense in Japan,” The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists,

According to Robert Eldridge, professor at Osaka University and currently attached to the US Marine Command in Hawaii, quoted in “Guamu kyotei shomei, towareru itsusu no gorisei,” editorial, Ryukyu shimpo, 18 February 2009. (See also miliHanda Shigeru, “Akumu ka, Obama seiken ka no Beigun saihen,” Shukan kinyobi, 16 January 2009, pp. 16-17.)

He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal. Posted February 22, 2009.

Recommended citation: Gavan McCormack, “Hillary in Japan – The Enforcer,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 8-7-09, February 22, 2009.

For a report on “Hillary in Beijing–Buy American” see Peter Harcher’s report in the Sydney Morning Herald.