The Nago Mayoral Election and Okinawa’s Search for a Way Beyond Bases and Dependence

By Gavan McCormack, Sato Manabu and Urashima Etsuko

1. Gavan McCormack:

Okinawa is far from Tokyo, even farther from Washington. An insignificant group of islands with a mere 1.3 million people, it is, more than anywhere, the child of the US-Japan relationship, in which the essential nature of both, and of their relationship, is starkly revealed. Insignificant . . . and yet, by their location between China and Japan, and between Japan and Southeast Asia, they are of extraordinary strategic significance in the postwar strategic calculus in the Asia Pacific region. Only in Okinawa does one become conscious that Japan’s “peace state” has long had its counterpart of Okinawa as “war state.” Now, as the rest of Japan faces the implications of US pressure to become a fully-fledged ally, the “Great Britain of the Far East,” and as forces associated with the Libral Democratic Party relish and seek to advance this prospect, it is to Okinawa that one may look to see what this might mean.

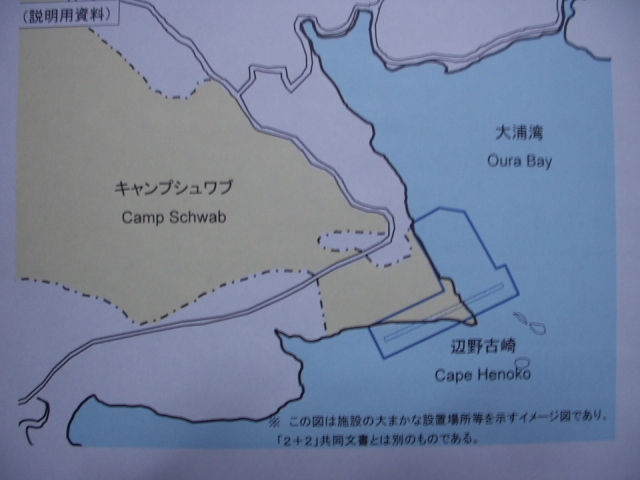

Under the SACO (Special Action Committee on Facilities and Districts in Okinawa) agreement of 1996, Futenma Marine Air Station, which sits incongruously in the middle of Ginowan township, was to be returned to Japan once alternative facilities were completed. Both governments agreed, however, that those alternative facilities would have to be in Okinawa. A 1997 plebiscite in Nago City rejected the idea of relocation there, but Governor Inamine Kei-ichi, who came to office in 1998, nevertheless went ahead and chose an offshore site on Nago’s relatively remote eastern side, provided only that it be a joint civil-military airport, its use limited to fifteen years, and there be no environmental damage. Late in 2005, however, construction works had still not even begun, so fierce and determined was local (and international) opposition. The two governments therefore changed their plan, adopting instead a site that could be partly built within the existing Camp Schwab base on Cape Henoko, with extensions on land reclaimed from Oura Bay, expanding the concept of the base by extending the runway from 1,500 to 1,800 meters and adding a Combat Aircraft Loading Area (CALA), and ignoring the conditions laid down by Inamine. The Governor declared his implacable opposition, as did all concerned Okinawan local government bodies, and a major crisis now brews.

Not only Okinawa, but all other local governments designated to play an increased military role in the future US-Japan alliance burden-sharing arrangements, reacted with opposition to the 2005 “Mid-Term” plan. At least one, Iwakuni in Yamaguchi prefecture, has decided to hold a plebiscite. The confrontation between Tokyo and the regions (whose autonomy is supposedly guaranteed under the Constitution) steadily sharpens. To deal with Inamine in Okinawa, the government is considering adopting a “Special Measures Law Concerning US Bases” designed to strip the Governor of his constitutional authority over the open seas and to simplify environmental assessment procedures. Tokyo also steps up its use of economic measures, fiscal pork barrel, to try to divide and buy off the opposition.

In the January 2006 election for mayor of Nago City, all three candidates declared themselves opposed to the revised plan. A conservative candidate, who intimated, however, that his opposition might not be absolute and that he would be prepared to discuss alternatives, was elected. Yet as of early February 2006 he had made clear his continuing opposition, and the head of Nago’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry asked whether Tokyo took the people of Nago for a bunch of idiots (Ryukyu shimpo, 7 February). The magma of political, constitutional, and diplomatic crisis began once again to rise thoughout Okinawa.

The dilemma of Okinawan local governments, from prefectural to village, is their structural dependence on bases. Since reversion from US to Japanese administrative control in 1972, eight trillion yen (roughly eighty billion dollars) has been spent, ninety per cent of it on public works, roads, harbors etc, supposedly to bring Okinawa to mainland levels of development. Such works were till recently 100 per cent subsidized, and still today are 90 per cent subsidized. The subsidies are compensation for the hosting of lion’s share of all US base facilities in Japan.

The subsidy system succeeded in raising Okinawan social capital to mainland levels, but income levels remain the lowest, at 70 per cent of the national average, and unemployment the highest, at seven per cent, in the country. The funds that continue to flow in seem unable to affect this “backwardness.”

When the prefecture teetered on the brink of outright confrontation with Tokyo following the 1995 rape of a 12 year-old girl by three GIs, one hundred billion yen was set aside for distribution to towns and villages that housed bases during the Seven Year Plan beginning in 1997, and from 2000, an additional one hundred billion was promised, over ten years, to Nago and its surrounds. Dependence on base-related subsidies reached as high as twenty per cent of revenue in the case of Nago city.

Also, the rental paid by the Japanese government for US base lands was steadily raised, from 12.6 billion at reversion in 1972 to 82.2 billion now, so that even if landowners were to have their land returned and were to use it for agriculture, they would actually suffer economic loss. Some, not surprisingly, no longer actually want their lands returned. The Japanese government’s “Sympathy Budget” has also grown, to 600 billion yen, much of which is spent on provision of services to the bases, which means provision of local community jobs, this too best seen as part of Tokyo’s base-promotion policy. In short, Tokyo assumes Okinawa has its price and provided the ante is steadily raised its discontent can be bought off.

Under this exceptional fiscal structure, Okinawa is blocked from any initiatives aimed at developing its unique characteristics or generating locally-rooted economic initiatives. Miyamoto Ken’ichi, Shiga University president and long-term critic of Japanese government policy on Okinawa, notes, “it is almost as if Okinawa were under direct rule by the national government in Tokyo,” i.e. that it is being denied its constitutional right to local self-government.

Sooner or later, Okinawa faces an inevitable fiscal and economic crisis as subsidies shrink under the reforms of local administration currently under discussion in Tokyo, and the top priority must be to find a way out of base dependence.

In the following essays, Sato Manabu, a political scientist at Okinawa International University, ponders the possibilities, in his article originally published in Asahi shimbun on 28 January 2006. Only by insisting on its constitutional rights, turning to maximum advantage the Tokyo government’s tentative, and so far insubstantial, talk of increased regional autonomy and ultimately pursuing the principle of “self-government”, can Okinawa’s demands be met. Sato speaks of “autonomy” and “self government,” not “independence,” but his arguments are bound to send a shiver down the spine of bureaucrats and politicians in Tokyo.

Urashima Etsuko, a Nago-resident environmentalist and author, writing in the February issue of the journal Shinshu Jichiken, gives a grassroots perspective on the local movement. Over the past decade the people of Nago have repeatedly fended off Tokyo’s attempts to foist on them a new base for the US marines. They have won many battles, but now they face a higher level of determination on the part of Japanese and US governments to ride roughshod over them. She offers her thoughts, from within this movement, on the recent mayoral election and its implications.

2. Sato Manabu:

In the Nago City mayoral election of 22 January 2006, Shimabukuro Yoshikazu, supported by the LDP and New Komeito, won, defeating two opponents. The main issue was that of the proposal to shift the Futenma US military base to a coastal area of Nago City. How are we to understand the victory by Shimabukuro, who opposed the government’s plan but was ready to consider a revised plan, over the two candidates who stood for simple rejection?

First, the election result was a serious blow for the anti-base movement. The opposition groups failed to agree on a candidate but even their two candidates together could not match Shimabukuro’s vote. They will have to come to grips with this coming spring’s election of mayor in Okinawa City and the autumn’s prefectural governor election, and rethink strategy. Electors at Nago were forced to make a painful choice.

Governor Inamine, who enjoys the support of the same LDP and New Komeito political forces as Shimabukuro, has held fast to his opposition to the Nago base since the October 2005 US-Japan Agreement on Base transfer. While on the one hand, the Governor supports Mr. Shimabukuro, local business and LDP groups that were part of their shared support group have adopted the position of favoring economic development through acceptance of the base transfer. Voters are troubled by these complex differences within the same camp.

As a result, the message the voters sent to the government was misleading. One hears it whispered about in Nago since the election that, “provided he can get the candy of some ‘development plan,’ the new mayor will give his assent.” Most likely that is also the view of members of the government in Tokyo.

However, even though the people of Nago city do hope for some economic development plan, Shimabukuro’s election should still be interpreted as saying “No” to the base, at least as presently proposed by Tokyo and Washington. Shimabukuro made clear his opposition to the present plan. It was his political pledge, and that is not to be overlooked.

The present base transfer plan was drawn up in accordance with a grand American design for military reorganization, with local people kept completely in the dark. To address the danger of Futenma Marine Base or to reduce the overall burdens on Okinawa were not major considerations, as the US itself has made clear. The latest Nago airport plan is for a Marine attack base completely different in character from Futenma, one that combines airport and naval port elements. At the same time, there is talk of a 7,000-man reduction in the marine force on Okinawa but most are support staff, while actual combat functions are to be reinforced. The real point of the present election result is that the people of Nago oppose base reinforcement.

Okinawa has until now had foisted upon it the choice of getting economic development in return for accepting the burden of the bases. However, Okinawa’s industrial base is still feeble and its per capita prefectural income the lowest in the country. As a result of constant, base-related, fiscal transfers, public and private sectors alike have grown more and more dependent. We have to realize that there is no future in trading off bases for economic development and that such a line of action has reached the end of the road.

As the merger of Japanese and US forces proceeds under the US military restructuring, it has become clear that the Japanese government looks on Okinawa only as a convenient bargaining chip. For Okinawa to create its own future there is no other path than to end its dependence on government through the bases and to build a relationship on an equal footing.

The government’s planned reforms of local administration provide Okinawa a god-given opportunity. For Okinawa to become a single shu (a kind of “super-prefecture,” with enhanced self-governing rights), in accordance with the plans currently under consideration by the national government, is going to mean that it will be pushed, willy-nilly, into autonomy anyway. So, why not move one step beyond the government’s plan and aim at a higher level of self-government, putting an end to dependence?

The path to autonomy will be hard. However, it is far better than a future in which we keep on taking the pittance from Tokyo that leads down the road to ruin. What is called for in Okinawa now is, above all, psychological independence. (translated GMcC)

3. Urashima Etsuko

Late January. In Nago City, the major town in northern Okinawa, the winter cherry is in full bloom. Here and there, dark pink blossoms dot the green of the mountains under the blue sky.

Crossing the island by Route 329 from the town center of Nago City that is bustling for the “Cherry Blossom Festival” (on 28 and 29 January), crossing the ridge that divides the island, to the East coast, overlooking the Pacific, it is hard to believe that these quiet hamlets, nestling scattered quietly in the folds of the hills, are part of the same Nago City. Here too the vivid flowers of the winter cherry are to be seen.

The Kushi district on Nago’s eastern seaboard was known as Kushi village up until 1970, when Nago City was formed by the merger of one existing town and four villages. In area, Kushi accounts for around one third of Nago City and in population about eight per cent (4,800 of 59,000 people). While the population of Nago as a whole has roughly doubled over the past eighty years, Kushi has not grown. The Okinawan word “kushi” means “after” or “back,” and since services here are always inclined to be left till last, local people are inclined to refer self deprecatingly to Kushi as the “after” or “last.”

In particular, even compared to the three settlements to the south of Henoko, on which Camp Schwab sits, the ten settlements to the north of Futami (where I live) suffer acute isolation and aging. Their present population in total is less than 2,000, and the four settlements that have primary schools are all facing crisis of merger or dissolution. Kayo Primary School, which my 16 year-old son attended, had 300 students at its peak, fifteen when he was there, but now has only three. Even when the Henoko district flourished from military base construction in the 1950s and services for the US troops thereafter, and population grew, these ten districts remained beyond the pale.

In response to the earnest desire of the region for something to put a brake on this deepening isolation, and to the desire for work to keep young people from leaving the district, what we have had on the boil since the end of 1996, has been the plan for construction of a new US military base – the airport to substitute for Futenma.

The world’s “North-South” problem is that of a rich north and a poor south, but in Okinawa it is the reverse. The contradictions of the urbanizing south press on the north, and then, within that north, the contradictions of the west press on the east. The ten districts to the north on the eastern coast, function rather as if they were the last repository of these contradictions. It is there that the plant for processing all the ordinary wastes of Nago Citywas built. In this context, residents of the district reacted with anger when they learned that a new US base was to be dumped on them but, at the same time, the fact is that the people here are desperate for work to avoid unemployment. So, for these past nine years, the base problem has been cause of unbroken anguish for us, setting parents and children, brothers and sisters, relatives and neighbors, at each other’s throats. The base problem, and the “money” that goes with it, have torn to shreds human relations based on cooperation and mutual help, relationships that used to be so rich even though we were poor, or rather, because we were so poor.

I belong to the “Association of the Ten Districts to the North of Futami that do not Want a Heliport.” It was founded in October 1997, during the outburst of activities leading up to the Nago City plebiscite on the base issue that was held on 21 December. As a local residents’ movement, it followed the formation of the “Stop the Heliport Council – Henoko Association for Preserving Life,” set up in January of the same year by the three districts centering on Henoko. The recollection of the more than 500 people – the elderly, children, couples with children in arms – who gathered from remote districts that you could walk through without ever seeing anyone, and where you might doubt that anyone actually lived, at Nago City’s Kushi District Hall to found it, will forever be etched on my mind.

From the beginning, compared to the “Three Henoko Districts,” the “Ten Northern Districts” had derived little economic “benefit” from the existing bases, while being exposed to their harm. With the exception of a few people, they were almost entirely anti-base. On the eve of the elections, the heads of the ten sub-districts all marched at the head of the demonstration through the heart of Nago to demonstrate the will of the people of the district. The struggle united the district.

However, when the expression of citizen’s determination of “No to the Base,” accomplished by the 1997 plebiscite campaign into which we had poured our hearts and souls and for which we had put our jobs and livelihoods on the line, was brusquely overturned by the then mayor, the sense grew that moves towards construction of the base were proceeding at some point beyond our reach, and the opposition movement gradually wilted. The sentiment of opposition to the base did not change, but people began to give up, thinking that, whatever we did, we could not defeat the authorities. Public facilities such as civic halls and schools and the like were refurbished one after the other and Defence Agency funds, salted with wads of ten thousand yen notes, forced people’s mouths, especially those of community leaders, shut. In the Ten Districts where aging was proceeding apace, clinics that had been sought in vain for years were built in no time at all with Defence Agency funds.

Though the numbers of participants in the activities of the “Ten Districts Association” fell off, we still took every possible opportunity and tried every device we could imagine to make the opposition of local residents known at city, prefecture and national government levels. Both the national government and Nago City regard only the “Three Districts” as the “designated area,” and even though a higher level of noise disturbance is predicted for it than for the “Three Districts” in the event of the airport being built, still the “Ten Districts” are considered only “surrounding districts,” and are left outside the net, without any explanation. When we submitted to Nago City a demand for a meeting of explanation, signed by two-thirds of the local residents, it was ignored.

Middle school protestor

After that, after eighty successive days of “Peace Present” activity calling on the Mayor’s office to hold an “Explanation Meeting for the Designated Area,” when we figured we had gained the unanimous support of the members of the town assembly, we ended up being turned down on a single word from the mayor. My 2002 book [in Japanese] “Fertile Islands have no Need of Bases” details some of the unique kinds of activities undertaken by the “Ten Districts Association,” including a mabuigumi (shaman) ceremony to restore his lost soul to the mayor. [Mabuigumi is the title of a novel by the well-known Okinawan novelist Medoruma Shun.]

In the February 1998 recall election for mayor, following one month after the then mayor had acted contrary to the will of the people expressed in the plebiscite by announcing his “acceptance” of the base and promptly resigned, the pro-base faction’s Kishimoto Tateo was elected by a narrow margin over the opposition candidate. In mayoral elections four years later, in 2002, Kishimoto was re-elected by a 9,000 vote margin. It seems to me that the fact that we are always defeated in elections even though the majority in opinion surveys is against the base is because we cannot overcome the strong sense of crisis on the part of pro-base people, including construction company-related people, that opposition to the base would mean loss of any development plan. The problem lies in formulating a compelling alternative non-base-dependent economic system or society. But, be that as it may, we local residents have endured constant suffering because of the base endorsing city government. After the defeat in the 2002 mayoral elections the opposition movement hit rock bottom, and the “Ten Districts Association” even had to declare a temporary suspension of its activities.

As individuals, we members of the Association participated in Okinawa-wide movements such as the sit-in and marine blockade to stop the seabed engineering survey of Henoko Bay beginning in April 2004, and in the local Henoko – Life Protection Association and Heliport Opposition (Nago City Liaison Council) and Okinawa-wide movements such as that by the Peace Citizens’ Liaison Committee.

Having forced the government to abandon its seabed engineering survey due to the force of pubic opinion supporting resolute, non-violent struggle, we are now confronted by the even bigger barrier of the exclusive military airport Henoko coastal plan “agreed” between the Japanese and US governments. For us residents of the Ten Districts, with the flight route passing directly over our hamlets and with concerns that the large-scale reclamation of Oura Bay is going to turn it into a military port, the crucial issue in the Nago mayoral election of 22 January had a crucial bearing. We would no longer be just “neighboring districts” but literally “designated area.”

If the plan is brought to realization, it is anticipated that the Ten Districts may become unlivable because of noise and the premonition of fishermen of Oura Bay who are overcome with a sense of crisis that “The sea will die!” Those of us who have suffered so much over these nine years pray fervently that, by one means or another, the base problem can be put behind us.

The candidates for successor after Kishimoto’s eight years all declared their opposition to the coastal plan. Even the cadidate succeeding Kishimoto declared his opposision to the

coastal plan, unable to unable to ignore the overwhelming public opinion, but suggesting, at the same time, that he may agree to a modified plan, andmany citizens feared that the day after might see a switch to a pro-base stand. Also, small and medium-scale businesses, who had not benefited from the “Northern District’s Development Plan” that was supposed to be compensation for the bases, suspected that there would be little benefit for them in airport construction work that would likely be monopolized by large, mainland construction forms; they wondered how they could escape from domination by the zenekon.

We prayed that in this election at last we would win, win come what may, and that we could restore Nago City, so long given the run-around by the base problem, to a healthy condition. But,- and how sad it is to relate – although this was our best chance, the anti-base camp put up two candidates, the vote was split, and the efforts of so many to create unity were in vain. In the end, both our candidates were defeated. Their total combined vote was just below that of Shimabukuro Yoshikazu, but the fact that the turnout was the lowest-ever Nago City poll (74.98 per cent) suggests that many who abstained did so out of disgust at the split. Most of them would have been anti-base. If you add to these the votes of whose who were anticipating a victory anyway, the consensus would probably be that a unified candidate could have won.

But this is no time for disappointment. The Ten Districts Association, which had suspended activities, has now resumed them. From then on, by taking an independent position on the election we were able to bring to the attention of people as a whole the views of local people normally not heard at all because of being a kasochi remote area. Links between the Ten Districts Association and the locality were revived by this election. The Henoko sit-in and the activities on the sea were necessary and I am proud that I was able to participate in them, but I now concede that during that period we were inclined to neglect our grassroots.

It is a fact that a pro-base city government will continue. But, whatever the city government, there is no way the base is going to be built easily so long as local solidarity is maintained. There are big problems to be overcome if we are to build a movement under present harsh conditions of extensive area, small population and rapid aging, but every one of the members of our movement has a fierce love for this region. Of course, opposition to the military base is primary, but together with that, the task facing us in the Ten Districts Association right now is to put our hearts and souls into finding a way to dig deep into our local resources to build a non base-dependent locality. (translated GMcC)

Written for Japan Focus and posted on February 16, 2006.