Helen McCullough translated and published the first twelve chapters of the medieval military chronicle Taiheiki, The Chronicle of Great Peace, in 1979. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Kyoko Selden and I, then colleagues on the faculty of Cornell University, began meeting weekly to read, discuss, and translate a broad range of Japanese historical texts, including sections of the Taiheiki through Chapter 19 (out of forty). Our short-term objective was to develop materials for an interdisciplinary seminar that would introduce more of the Taiheiki to English readers. In this special issue, two selections from the Taiheiki—the dramatic and tragic death of Go-Daigo’s cast-off son Prince Moriyoshi (alt. Morinaga, 1308-35) from Chapter 13 and an account of the critical battle at Hakone Takenoshita from Chapter 14, both events of 1335—are paired with linked verse by the basara (flamboyant) warrior Sasaki Dōyo, and the Edo-period Hinin Taiheiki: The Paupers’ Chronicle of Peace. All were originally translated and annotated for our Taiheiki course, first taught in 1992, a class that I continue to teach at the University of Southern California.

By way of brief introduction to the Taiheiki, we know neither its authors’ names nor its completion date. Criticisms of the Taiheiki (Nantaiheiki) by Imagawa Ryōshun (active 1370s-1440s), compiled in 1402, suggests that an initial account took form between 1338 and 1350, but editing and expansion continued long after, into the era of the third Ashikaga shogun, Yoshimitsu (1358-1408; reign 1368-94). Literary historian Hyōdo Hiromi thinks that an early text of thirty chapters was expanded by an additional ten chapters.1 The journal of the well known courtier Tōin Kinsada (1340-99) names the monk Kojima as one author, while Imagawa’s Criticisms of the Taiheiki mentions two other monks, Echin and Gen’e, as compilers. Gen’e was an intimate of Ashikaga Takauji’s younger brother and lieutenant Tadayoshi (1306-52), as well as a prominent scholar of China’s Sung dynasty (960-1279). Since both Echin and Gen’e died in the 1350s, they would have been early contributors to the manuscript.2 As for the issue of how the early story was written, historian Satō Kazuhiko thinks that, at least for battle narratives, the authors used records made by Ji-sect monks, who followed armies of the day and tended to funerary rites on the battlefield. In some cases we also have reports of battle service called gunchūjō submitted by warriors to claim rewards.3

The Taiheiki can be divided into three chronological sections: the first twelve chapters provide the narrative up to the fall of the Kamakura Shogunate in 1333—this was the section translated by McCullough. The next nine chapters (13-21) tell the story of the monarch Go-Daigo’s restoration, its failure, and Go-Daigo’s subsequent death in Yoshino in 1339. And the final nineteen chapters (22-40) narrate the fortunes of the newly established Ashikaga Shogunate up to 1367, including battles between adherents of the northern and southern courts, the fracturing and inner struggles within the Shogunate between supporters of Takauji and Tadayoshi in the 1350s, and the back story for the reign of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu that began in 1368. While the Selden-Piggott translation does not yet include chapters from this third section, we have translated the titles of each subsection and written abstracts for them, which provide readers with a good sense of the contents of each subsection. The plan is to put all this work on the Japan Historical Text Initiative (JHTI) website in the near future,4 providing a platform where multiple translators can work on sections simultaneously to advance the ongoing translation project more quickly.

As for historical context, the knowledge of which greatly enriches a reading of the Taiheiki, English readers can find useful material in Andrew Goble’s The Kenmu Revolution (1997), Kenneth Grossberg’s Japan’s Renaissance (1981; reprinted in 2010), and Thomas Conlan’s two studies, State of War (2004) and Sovereign and Symbol (2011).5 Fortunately, in these books Conlan has begun to develop the new field of Nanbokuchō historical studies—that is, the history of the era of warfare between supporters of the two courts, north (in Kyoto) and south (in Yoshino and Kawachi), from 1336 to 1392—in English.

In terms of style and genre, the intellectual historian Ōsumi Kazuo has noted strong influence from the Heike monogatari (Tales of the Heike, compiled in the mid-fourteenth century) battle narratives on the Taiheiki descriptions of warfare.6 Nevertheless, the sustained depiction of bloody and unending civil war and the fissuring of society at all levels over several decades distinguishes the Taiheiki story, even if blind monk Akashi no Kakuichi’s Heike (the best known edition of the text, completed in 1371) and extant versions of the Taiheiki—far fewer than those of the much larger Heike opus—took form around the same time. The sharp critique of politics and society in the Taiheiki evokes the Chinese historiographical tradition of “praise and blame” that dates back to the Han dynasty Historical Records (Shih chi in Chinese, Shiki in Japanese). And while some researchers have questioned its historical authenticity, the Taiheiki is frequently cited by historians.7 For instance, Satō Kazuhiko’s research on “evil bands” (akutō), the mentalité of “lowers overcoming betters” (gekokujō), and other aspects of society and culture in the fourteenth century draws extensively on insights from the Taiheiki.8 Hyōdo Hiromi actually reads the Taiheiki as the chronicle of the Ashikaga Shogunate, arguing that it served a function similar to the earlier Azuma kagami (Mirror of the East, circa 1266) for the Kamakura Shogunate. And Ōsumi sees the Taiheiki as a primer (ōraimono) from which medieval readers took away basic lessons on both the classical texts of China and Japan, as well as knowledge of events associated with the fall of one warrior government, the rise of another, and the hostilities between the northern and southern courts.9

To conclude, having a fuller English translation of this important historical chronicle is a goal that Kyoko and I espoused, and we worked over many years to advance that objective. Future plans for the results include making more of our Taiheiki translation accessible to readers online, interspersed with the Japanese text of the Survey of Classical Japanese Literature (Nihon koten bungaku taikei)10 on the website of the Japan Historical Text Initiative at the University of California, Berkeley. We will also publish a set of Taiheiki-related materials, including Imagawa Ryōshun’s Criticisms of the Taiheiki, which we have already translated, to provide additional historical context for English readers of this important account of war and peace in medieval Japan. I am so glad to see some of that work published herein.

|

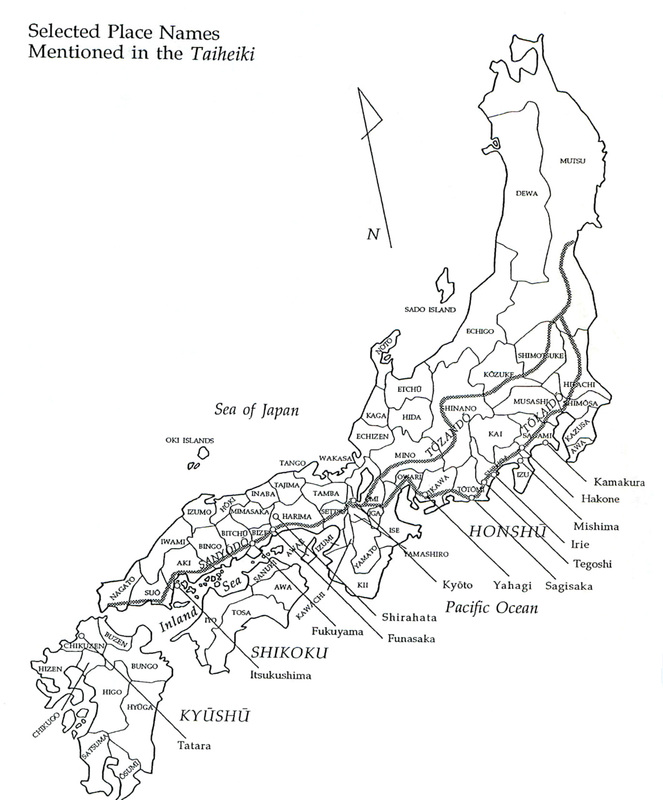

Selected Place Names Mentioned in the Taiheiki. Original map created by Joan Piggott. |

Introduction to the Translated Sections

Chapter 13 begins with a series of ominous events: Go-Daigo Tennō’s trusted minister Madenokōji Fujifusa (also known as. Fujiwara Fujifusa, 1295-1380?) forcefully criticizes Go-Daigo’s restoration government, drawing parallels from Chinese history. He then resigns to become a hermit in late 1334. In 1335 Saionji Kinmune (1310-35), from the family that had long served as shogunal liaisons (mōshitsugi) at the Kyoto court, plots the assassination of Go-Daigo in order to restore the Kamakura warrior government. But Kinmune’s treason is revealed, in part by a series of heavenly signs, and he is executed. Then Hōjō Takatoki’s son, Tokiyuki (?-1353), who survived the fall of Kamakura in 1333, rises in rebellion with backing from some eastern warriors. Dubbed “the Heike” in the Taiheiki—thereby reprising Heike monogatari stories of earlier Gempei warfare (1180-85)—these “Hōjō remnants” strive to retake Kamakura. Faced with this challenge, Go-Daigo solicits General Ashikaga Takauji’s help, but Takauji is initially unwilling to fight unless he is named premier warrior of the realm, that is, shogun. In the end, however, Takauji heads east to fight without that appointment. He is encouraged when his troops swell from 500 to 30,000 as he proceeds up the Eastern Sea Road. Meanwhile, his brother Ashikaga Tadayoshi (1306-52), then in Kamakura and facing the brunt of the rebels’ attack without adequate defenses, is forced to withdraw and join Takauji. As he does so, he orders the execution of Go-Daigo’s son, Prince Moriyoshi, whom the Ashikaga had been holding under arrest by royal order since 1334. Scenes from that execution are described in our first translated section.

We know from the final sections of Chapter 13 that Takauji and his forces subsequently bested the Hōjō forces in battles fought around the Hakone area, and that Takauji then began using the title of “shogun.” In the first section of Chapter 14, we also witness the dueling memorials submitted to Go-Daigo by His Majesty’s rival commanders in the tenth month of 1335—Takauji and his cousin, Nitta Yoshisada (1301-38). Each argues, albeit with quite different rhetoric, that he himself is the most loyal and capable royal defender. Ultimately, Nitta gets the nod—in part due to the murder of Prince Moriyoshi—and is ordered to pacify Takauji. A long list of those who joined the royal force follows. As it set out in the eleventh month, the force of 320 lords and 67,000 troops reportedly stretched from the capital to Atsuta Shrine in today’s Nagoya, far up both the eastern mountains and sea routes. This catalog of royal generals comprised a critical record for later descendants of those who supported the throne at this epochal moment of Go-Daigo’s restoration.

What happened to the Ashikaga ranks reads less heroically. Takauji himself initially refused to fight the royal force; he withdrew to a monastery, while his brother Tadayoshi took the army—reportedly numbering between 200,000 and 300,000 troops—to Mikawa and Suruga for battles at Yahagi, Sagisaka, and Tegoshigawara in the late eleventh and early twelfth months of 1335. Despite the fact that Nitta’s army was severely outnumbered, they were still able to force the Ashikaga to retreat, at which point Takauji’s fellow generals faked a royal order from Go-Daigo promising to destroy all the Ashikaga family whether they fought or not. That edict finally moved Takauji to rejoin the battle. With Takauji back in service, the Ashikaga won a decisive battle just a few days later at Takenoshita in the Hakone area, on December 11, 1335. That victory, which swelled the army of the Ashikaga side and resulted in the dispersal and flight of Nitta’s forces, is the subject of our second translated section.

Notes

Hyōdō Hiromi, Taiheiki yomi no kanōsei: rekishi to iu monogatari (Reading the Taiheiki, History as Narrative) (Tokyo: Kodansha Sensho Mechie, 1995), 1-43, esp. 27.

See Paul Varley’s discussion in Steven D. Carter ed., Dictionary of Literary Biography. Volume 203: Medieval Japanese Writers (New York: Gale Group, 1999), 283-86.

Satō Kazuhiko, “The Society of the Taiheiki,” in Okutomi Takayuki et al., Nihon no chūsei, sono shakai to bunka (Medieval in Japan, Society, and Culture) (Chiba: Azusa Shuppansha, 1983), 105-28. Recent research that adds many new insights to this discussion is Kitamura Masayuki, Taiheiki sekai no keishō (Images of the World of the Taiheiki) (Tokyo: Hanawa Shobō, 2010). Ji Sect is a branch of Pure Land Buddhism that formed around itinerant preacher Ippen Shōnin in the thirteenth century.

Andrew Goble, The Kenmu Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Council on East Asian Studies, 1997); Kenneth Grossberg, Japan’s Renaissance (Cambridge: Harvard University Council on East Asian Studies, 1981; republished by Cornell East Asia Program, 2010); Thomas Conlan’s State of War (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Center for Japanese Studies, 2004); and Sovereign and Symbol (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). Also useful is Paul Varley, “Cultural Life in Medieval Japan,” in Kozo Yamamura, ed., The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 3 (Medieval), especially 458-81 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990); G. Cameron Hurst, “Warrior as Ideal for a New Age,” in Jeffrey Mass, ed., The Origins of Japan’s Medieval World (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), 209-36; Thomas Conlan, In Little Need of Divine Intervention (Ithaca: Cornell East Asia Series, 2001); Lorraine Harrington, “Regional Administration under the Ashikaga Bakufu,” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Stanford University, 1983); Karl Friday, Samurai, Warfare, and the State in Medieval Japan (Oxford: Routledge, 2004); and Andrew Goble, “GoDaigo, Takauji, and the Muromachi Shogunate,” in Karl Friday, ed., Japan Emerging (Boulder: Westview Press, 2012), 213-23. Other chronicles of the same era that have been translated into English are Shuzo Uenaka, A Study of Baishōron (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Toronto, 1978) and George Perkins, The Clear Mirror, Masukagami (Stanford: Stanford University Press,1998).

See his entry for the Taiheiki in the Kokushi daijiten (Great Dictionary of National History) (accessed through Japan Knowledge, accessed February 16, 2014.

For instance, dates for the battle of Takenoshita in the Baishōron, also compiled in the mid-fourteenth century, differ from those in the Taiheiki, and those in the former have been determined to be correct. See “Taiheiki, Baishōron kara mita Hakone, Takenoshita no tatakai” (accessed January 12, 2014).

See Satō Kazuhiko, Taiheiki no sekai (The World of the Taiheiki) (Tokyo: Shinjinbutsu Ōraisha, 1990). For class use, Piggott and Selden translated Satō’s essay, “Taiheiki as Nanbokuchō-era Literature” (Taiheiki, Nanbokuchōki no bungaku toshite), which is a rich introduction to his reading of the Taiheiki. See Okutomi, Takayuki et al., 1983, 105-28.

Ōsumi Kazuo, Chūsei rekishi to bungaku to no aida (Between History and Literature in Medieval Times) (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 1993), esp. 198-216.

Nihon koten bungaku taikei (Anthology of Japanese Classical Literature), vols. 1-3 (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1960-62).