Article Summary: This article explores tanka poetry published shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack as a window into the initial public reaction in Japan to the outbreak of the Pacific War. We show that whereas tanka became a powerful tool of propaganda in the hands of professional poets, it also allowed amateur poets and political figures to express their private, diary-bound dissent.

|

On December 8, 1941—seventy-five years ago—people across Japan woke to the most surprising news. At 7 a.m., the press released the following bulletin from Imperial Headquarters: “Today, on December 8, before dawn, the Imperial Army and Navy entered into a state of war with U.S. and British forces in the western Pacific.”1 A few hours later, at 11 a.m., the Cabinet released the imperial rescript declaring war on the United States and Great Britain. People glued to their radios would soon learn that Japan had launched a daring and successful surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, and had begun operations against British and American territories throughout Southeast Asia. This news electrified the populace, generating a widespread euphoria and jingoism that perhaps exceeded any other event in Japan’s modern history.2 From schoolchildren to professors, writers to critics, military men to civilians, people across Japan reacted with jubilation.

The war served as a call to arms for poets as well. In a manifesto published in March 1942, writer and poet Nishio Yō spoke to the unique role poets and patriotic verse (aikokushi) could play in Japan’s war. “Poets fight by taking up the pen,” he argued. Nishio recognized that patriotic verse had a twofold significance: to mobilize Japanese toward “victory in war,” and to seize a “victory in culture” that, presumably, would establish Japan as the leading power in the region. “Poetry,” Nishio concluded, “has never had as important a function as today.”3

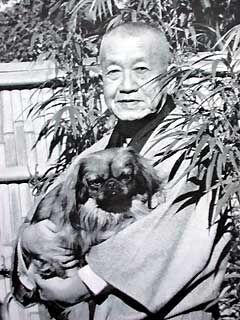

But Nishio was in fact describing a trend that had begun months earlier. December 8, 1941, in particular, constituted an awakening for many poets, who met Pearl Harbor and the Greater East Asia War with enthusiasm and support. Kitahara Hakushū, Japan’s poet laureate, best encapsulated this awakening in a tanka published in February 1942:

|

Kitahara Hakushū |

天皇の戰宣らす時をおかずとよみ搖り興る大やまとの国4

|

|

A striking and less-known fact, however, is that tanka was not only mobilized in the service of empire; it was also used to express private dissent. This essay explores tanka poetry written shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack as a window into both the public fervor and private anxieties of early Pacific War Japan.5 Tanka is particularly useful to this end: it was revered as the oldest native and most Japanese of all literary forms, and was widely used to commemorate events of great significance.6 Professional and amateur poets alike used it after the war had begun to express everything from enthusiasm to reverence to outright opposition. On the one hand, popular publications like Bungei shunjū mobilized the most famous poets of the day, providing space for them to publish poems that highlighted the necessity, the beauty, and the grace of Japan’s new war for Asia. On the other hand, some amateur poets and political figures took to tanka to express unpublished, diary-bound dissent. Existing scholarship in both Japanese and English largely eschews a broader focus on how poetry, tanka in particular, can shed light on the initial public reaction to Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of the Pacific War.7 In combining both professional and amateur poetry, we hope to paint a more complex picture of popular and literary responses to Japan’s declaration of war against the Allied powers.

Tanka and Private Dissent

|

Ozaki Yukio |

Not everyone throughout Japan met the news on December 8th with enthusiasm. Former Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro and former Foreign Minister Matsuoka Yōsuke, the two civilian leaders most responsible for the drift to war, had become bitterly critical and worried that Japan’s good fortune would not continue for long.8 Hirohito’s uncle, Prince Higashikuni Naruhiko, too, grieved in his diary on December 8th. “Japan had taken its first step to ruin,” he wrote, “and I was disheartened.”9 Strikingly, however, the most forceful critiques were made through tanka, by politician Ozaki Yukio and political scientist Nanbara Shigeru.

Ozaki Yukio was Japan’s maverick elder statesman, an independent politician who served a storied six-decade term in the House of Representatives. Widely revered as Japan’s “god of constitutional politics,” Ozaki led the fight for universal male suffrage in 1925, and through the 1930s supported arms limitation and criticized the military’s growing influence in Japanese politics. He reacted to Pearl Harbor with great trepidation. Ozaki worried about the “ecstatic response” that met news of Japan’s “unexpected military achievement,” and penned two poems in response.10 The poems would not be published until 1952.

桶狭間の奇勝におごり本能寺の奇禍を招ける人な忘れん11

|

|

詰手なき将棋をさしつつ勝ち抜くと嘯く人のめでたからずや13

|

|

These poems serve as strong indictments against Japan’s war for mastery over Asia. The first poem’s arrogant victor is a reference to Oda Nobunaga, the first of Japan’s three great unifiers during the warring states era. Ozaki hints that although Nobunaga won a great battle at Okehazama in 1560 that established him as one of Japan’s pre-eminent warlords, the resulting arrogance invited his untimely demise. In 1582, while staying at Honnōji Temple in Kyoto, Nobunaga ultimately let his guard down. One of his leading retainers, Akechi Mitsuhide, betrayed Nobunaga, setting fire to the temple and giving him no recourse but to commit suicide. Nobunaga met his end before fulfilling his dream of uniting the realm. This first poem thus mocked the misplaced jingoism of Japan’s new war, and warned that the seeds of Japan’s future defeat were already sown in the skies above Pearl Harbor and the jungles of Malaya.

|

Nanbara Shigeru |

The second poem is an even stronger attack on the jingoism prevalent in Japan’s military and political establishment. Pearl Harbor, Ozaki suggests, cast a veil over the eyes of Japan’s military and political leaders. This one battle led them to deceive themselves that victory is in Japan’s grasp. But no amount of wishful thinking would lead the war to a successful end. To Ozaki, the war against Britain and America was a “fool’s errand.” Together, his poems justify one historian’s view of him as “a persistent critic of both actors and audience.”14

Political scientist and Tokyo Imperial University Professor Nanbara Shigeru used poetry in similar ways. Nanbara kept a private collection of tanka poems that he used to criticize Japanese policy and the drift toward war. His poems denounced the Tripartite Pact, the Konoe Cabinet, the concentration of power under Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki, and the likelihood of war with the United States.15 When war broke out on December 8, Nanbara composed three poems that convey his deep distress. These poems would be kept under lock and key until 1948, three years after the Japanese surrender.

人間の常識を超え学識を超えておこれり日本世界と戦う16

|

|

日米英に開戦すとのみ八日朝の電車のなかの沈痛感よ17

|

|

民族は運命共同体といふ学説身にしみてわれら諾はむか18

|

|

Nanbara’s variable meter tanka went against the grain of contemporary tanka practice, which had turned away from experimentation in the late 1930s.19 But his message is clear. The war was against any notion of common sense or understanding, and its outbreak was something that brought him great sorrow. Still, Nanbara remained committed to Japan’s cause. The final poem highlights Nambara’s sense of duty to support his nation even in something he vehemently opposes. Although Nanbara saw the war as “wrong-headed,” he still considered it the people’s duty to share in the nation’s sufferings. The people, after all, were bound together in a community of collective fate: what affected one, affected all. As Nanbara eloquently noted in 1963, nearly twenty years after war’s end, “I have never felt so painfully as then the fact that for better or worse, politics and the people aren’t separable, that the nation constitutes a community of fate.”20 .

Both Ozaki and Nanbara had little recourse but to keep their poems private. Speaking out in opposition during wartime Japan, after all, brought great personal and social risk. From the early 1930s, assassinations had become so widespread that they were an essential feature of Japanese political life.21 At a very real level, taking a stand could invite one’s untimely demise. More importantly, thought-control policies threatened would-be protesters with prison or even capital punishment. The state since 1925 had used the Peace Preservation Law (which was revised for the third time in 1941) to suppress dissident organizations and heterodox views.22 Japan thus lacked any powerful independent organization that could shield people who spoke out in opposition. In fact, Ozaki would ultimately be indicted for lèse majesté for accusing Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki’s government of unconstitutional electoral manipulation in the general election of April 1942. Finally, fears of social ostracism played a critical role, with loyalty and harmony glorified as among the highest social values. Social ostracism and legal retribution may have been of particular concern to Nanbara, whose Christian beliefs were seen in wartime Japan as heretical and possibly subversive.23 In this highly authoritarian climate, it is no wonder that people were unwilling to publish direct and powerful criticisms of the war.

Lacking any formal means of protest, Nanbara and Ozaki privately turned to tanka to express their innermost thoughts. This is unsurprising. Tanka poetry served as an important medium—both public and private—to commemorate occasions of significance or to convey one’s emotional state. Moreover, tanka constituted a relatively safe form of private protest; the poems were sufficiently opaque that authors could be confident that censors would not decipher them correctly. In commemorating Pearl Harbor and the opening of hostilities against the Allied powers, Nanbara and Ozaki’s tanka highlight how this poetic form could be used to articulate private dissent against a society and polity mobilized for an unwinnable war.

|

Tanka Mobilized for War

Unlike amateurs like Nanbara and Ozaki, most famous tanka poets lent their support to Japan’s war for Greater East Asia. They found a strong platform in Bungei shunjū, a prominent literary journal and news magazine. Bungei shunjū by the late 1930s had emerged as an important conservative magazine, lending its weight in support of Japan’s kokutai (national polity), empire, and wars for Asia.24 The editorial staff saw tanka, haiku, and other poetic forms as playing an important role in Japan’s war. By 1942, the magazine had become one of the few widely read general-interest magazines containing dedicated sections for patriotic tanka and haiku. In January and February 1942, Bungei shunjū commemorated the declaration of war by publishing poems from the most famous poets of the day.25 The tanka section included works by Kitahara Hakushū (1885–1942), Kawada Jun (1882–1962), Toki Zenmarō (1885–1980), Shaku Chōkū (1887–1953), Saitō Ryū (1879–1953), Onoe Saishū (1876–1957), Yoshii Isamu (1886-1960), Sōma Gyofū (1883–1950), and Oyama Tokujirō (1889-1963). It was in part through Bungei shunjū that these tanka poets reached a broader audience; the journal helped mobilize poetry in the service of empire and war.

This use of poetry was a new development. The Manchurian Incident of 1931 and the China Incident of 1937 were both wildly popular events, but did not generate an explosion of patriotic verse in highbrow journals. But the editorial staff at Bungei shunjū viewed December 8, 1941 as a turning point not just for the world, but for the world of tanka as well. In January 1942 the journal wrote, “This day, which should be memorialized as a new departure for East Asia, nay, the world, and for Japan as well. This is also a day from which the world of tanka poets must start anew.”26 The following month, the journal also included a note that upon hearing the announcement of Japan’s victories, “The people, at once, were no longer the people of yesterday. Tanka poets, too, can no longer be the tanka poets of yesterday. The very appearance of tanka (tanka no fūbō) has completely changed.”27 Tanka poets answered this call to arms by creating new poetic tropes like the Imperial Edict (mikotonori) that announced Japan’s entry into war, and by highlighting themes of victimization, vengeance, glorious death, and deep emotion or reverence.

Victimization and Retribution. One of the most common strands of tanka hinted at a profound sense of victimization and future retribution. This sense of victimization had deep roots in Japan’s engagement in international politics. Many felt that Japan had been dragged into the dog-eat-dog imperialist world, a world in which the cards had been stacked unfairly against their nation. From the 1930s, after being condemned for invading Manchuria and establishing the puppet government of Manchukuo, government propaganda spun a narrative of Japan as isolated in a hostile world.28 U.S.-Japan relations in 1941 only served to reaffirm this point. Washington responded to Japan’s occupation of southern French Indochina with economic strangulation. The United States froze Japanese assets, initiated a full economic embargo, and issued the Hull Note, which called on Japan to withdraw troops from Indochina and China. But these moves fed into the sense among many Japanese of being bullied and humiliated in international affairs. Many came to believe that the United States failed to understand the “pure motives” or “sincerity” behind Japanese actions in China and Indochina, and was browbeating Japan into becoming a third-rate power.

The December 8, 1941 imperial rescript declaring war on America and Britain reinforced this victim narrative. Japan, the rescript stated, had only the purest of motives. It only sought stability, peace, friendship and “prosperity in common with all nations.” But Japan’s enemies failed to understand its true intentions. Instead, they presented new challenges at every turn. They threatened Japan with military preparations, obstructed Japan’s “peaceful commerce,” and even severed economic ties, “menacing gravely the existence of our Empire.” Japan had patiently endured this foreign menace, but the time for waiting had passed. The imperial rescript concluded, “our Empire for its existence and self-defense has no other recourse but to appeal to arms and to crush every obstacle in its path.” Japan, in short, was victimized into taking up arms.29

Poets echoed this victim narrative. Kitahara Hakushū published the following tanka in February 1942, a few months before his death.

長き時堪へに堪へつと神にしてかく歎かすか暗く坐しつと30

|

|

This poem evokes fierce support for Japan’s imperial project by positioning not just the Japanese people but even their gods (kami) and Emperor (a living deity) as victims. Contemporary readers would have noticed the similarities with the imperial rescript, especially its assertion that Japan had endured mistreatment by America and Britain. The explicit message of the rescript underlies this tanka as well: Japan had no recourse but to strike.

Whereas gloom was pervasive in Kitahara’s tanka, other poets were more vocal about the wrath, the beauty, or the refreshing feeling of finally casting off this victimhood and striking back. For instance, Shaku Chōkū (1887–1953), the tanka nom-de-plume of eccentric novelist and folklorist Orikuchi Shinobu, published the following poem in January 1941.

神怒り かくひたぶるにおはすなり今し斷じて討たざるべからず31

|

|

Shaku was known to produce works replete with romance, sexuality, and ghosts. He was also a scholar of Shintō and the Man’yōshū (the earliest extant Japanese poetry anthology, from the 8th century C.E.). His take on a post-Pearl Harbor tanka transmutes his interest in the supernatural and historical drama into propaganda: in his hands, the call to war becomes almost shamanic. Like Kitahara, Shaku here describes the Japanese people as of one mind with their gods. But whereas Kitahara’s gods weep alongside the suffering people, Shaku’s gods arrive in wrath and chaos, sweeping the populace along with them. This emphasizes the outbreak of war as inevitable, just, and divinely ordained.

|

Toki Zenmarō |

Prolific poet and journalist Toki Zenmarō gleefully awaited the time when America and Britain would reap their due rewards. The following poems, both published in February 1942, paint America and Britain cartoonishly as a “tyrannical” (ōbō) villain and “crafty” (rōkai) sidekick, and highlight a sense of joy that Japan can finally fight back.

横暴アメリカ老獪イギリスあはれ生耻さらす時に來向ふ32

|

|

His next poem is in the same muscular, pulpy style befitting his journalistic background.

撃てと宣らす大詔逐に下れり撃ちてしやまむ海に陸に空に33

|

|

This poem highlights the excitement and relief of the decision to take retribution, a decision long in coming. Toki’s enthusiasm is accentuated by his use of the common World War II slogan “shoot them down to the last man” (uchiteshi yamamu, shoot to no end, or keep up the fight). This phrase, taken from the early 8th-century Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters), called to mind the sacred origins of Japan, when mythical Emperor Jinmu rallied his forces to subjugate the Japanese isles. In this context, it tied the “never surrender” spirit of Japan’s modern military to the ancient founding of Japan, and legitimized Japan’s fight against the Allied powers.34

This is also the first example of many among these tanka that uses the most significant of new poetic tropes: the mikotonori, or “Imperial Edict,” referring to the Emperor’s official rescript declaring war following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Mikotonori appears in several of these works, and also fits perfectly in a 5-syllable line; it appears in a 7-syllable variation here, as ōmikotonori. Other widely used terms for the same concept include dai shōchoku or dai chokugo. The edict—published on the front page in every newspaper and announced on the radio—became a new and emotionally charged poetic theme, reference, and phrase.

|

Saitō Ryū |

Saitō Ryū, a former general and well-known poet who helped form the nationalistic Great Japan Tanka Poets Association, wrote a poem with a similar sentiment on December 8, 1941.35

英米を葬るとき来てあな清し四天一時に雲晴れにけり

|

|

|

Takamura Kōtarō |

Like Toki, Saitō highlighted the feeling of excitement at meting out punishment to Japan’s two powerful enemies. But whereas Toki’s first poem looks upon Japan’s doomed enemies with disgust and sarcasm (“what a pity” is their fall from grace), Saitō saw Japan’s bloody fight as a “refreshing” (sugashi) moment that approaches ecstasy. In a sense, Saitō’s poem best captures the popular attitude toward the new war. No longer would Japan dither and dally, hoping for an unlikely breakthrough in its negotiations with the United States, which had dragged on since March.37 In launching war, the path forward had become clear. Japan would “slaughter” the very bullies that sought to intimidate it into submission.38

Long form poetry, too, took up these very same themes. Perhaps the most famous of these is “December 8th” by Takamura Kōtarō (1883–1956). This was an unusual poem for Takamura, a poet and sculptor best known for Chieko Poems (Chiekoshō), a melancholy collection published in 1941 about his wife’s struggles with mental and physical illness and early death. Given that “December 8th” epitomizes the feeling of long-term victimization and the righteousness of Japan taking retribution against the “Anglo-Saxon” powers, it is worth quoting in its entirety.

|

|

|

***

Death. Death and heroic sacrifice constituted a second main theme upon which tanka poets drew. This ultimate sacrifice was often utilized to highlight themes of duty to one’s lord, loyalty, regret, and ephemerality. But in the aftermath of the Manchurian Incident of 1931, death in particular emerged as an important trope of patriotic literature. “Tales of heroism,” or bidan, highlighting noble deaths for the nation, became a popular cultural form appearing in the news, in popular magazines, and even on the stage and silver screen. As Louise Young has shown, these “tales of heroism” focused on acts of self-sacrifice: a soldier’s heroic death, or a housewife’s sacrifice of livelihood. “Tales of heroism” tied both battlefield and homefront in a mass-media driven culture of sacrifice for the nation.40 This theme of sacrifice became even more commonplace after Pearl Harbor. Japan’s total war pressed soldiers and civilians alike to sacrifice themselves for the nation; poets thus stressed a readiness to die that even Japanese subjects on the home front must embrace.

A tanka by Saitō Ryū written shortly after the outbreak of war best highlights this trend.

一億の民たたかひて盡くらくは滅ぶるにしてや潔よからむ41

|

|

“The hundred million” (ichi oku) was a common shorthand to describe the Japanese nation, expressing both the vast number of subjects and their unity in purpose. In struggling as one, placing their very existence on the line, Japan could transform its very destruction (horoburu, “fall to ruin”) into a glorious and “graceful” event. In a sense, Saitō was ahead of his time. The beauty or grace of national ruin, emphasized by the phrase gyokusai, or “to die gallantly as a jewel shatters,” would become a common trope after the war turned against Japan in 1943.42 The term was first introduced in May 1943, when U.S. forces retook Attu Island in the Aleutians near Alaska. And by June 1944, the Army Section of the Imperial General Headquarters called for the gyokusai of Japanese forces in Saipan in the hopes that “the enemy, fearing a hundred million shattered jewels (ichi oku gyokusai), would abandon their will to fight.”43

Yoshii Isamu also took up this theme of death in a poem published in February 1942.

大詔聽きつつ思ふいまわれら大君のため死ぬべかりけれ44

|

|

|

Yoshii Isamu |

Yoshii was a romantic poet and author of some of Japan’s first radio dramas, but this tanka evokes a dramatic radio moment more intense than any he could have come up with: the declaration of war. Yoshii here emphasizes the intensity of the experience of learning about the war through a double-meaning, with omou ima warera (I think, now we) almost perfectly containing the phrase omoi maware (thoughts surrounding/revolving). The layering of meaning captures the feeling of listening to the declaration of war while considering the inevitability of a glorious death in the name of the Emperor.45

Finally, this theme of death was taken up by Kawada Jun, perhaps the most prolific and best known of wartime tanka poets, who released two volumes of patriotic tanka during the war.46 In this poem, published in February 1942, he stresses death as a necessity for the justness of Japan’s cause.

たたかいは朕が志ならずと宣り給ふ大詔勅に命は捨てむ47

|

|

This tanka directly references the imperial rescript declaring war, highlighting the fact that war was brought upon the Emperor against His Majesty’s wishes. This is expressed through the majestic imperial pronoun chin (the royal “we”) reserved for the Emperor’s use. The last two lines turn to the poet’s thoughts. Kawada makes use of the edict of war—here rendered as dai shōchoku—as a symbol for Emperor, Empire, and Nation, the ideals for which Japanese subjects must be ready to “lay down” (sutemu, or “throw away”) their lives. By laying down their lives, Japanese subjects could help win the war against a powerful foe and gain glory for the nation.

***

|

Kawada Jun |

Deep Emotion. Whereas traditional Japanese poems like tanka and haiku are known for their restrained diction—implying feelings obliquely rather than explicitly—what is striking about wartime works is their heightened emotional state. The imperial rescript declaring war provoked an intense emotional reaction or visceral whole-body experience in the poet. In this sense, tanka poets reflected the broader trend among writers, from poets to prose essayists, who described December 8th through the terms “deep emotion” (kangeki) or being “moved to tears” (kanrui).48

Tanka written from the frontlines would have had little problem evoking a profundity of feeling. But the poets here, all older men on the home front, had to take a different approach. Kawada Jun laid out his approach in a 1943 essay, “My Attitude Towards War Tanka (Sensō tanka e no taido).”49 He created two broad categories of poems. The first were tanka that convey the everyday wartime experience of those at home. The second were verses that engage with news media, either evoking scenes of war as depicted in the newspaper or on the radio, or about the poets reflecting on the act of reading newspapers or listening to radio broadcasts. Instead of making dense allusions to famous works of literature and myth, Kawada sought to express deep emotion through everyday experiences and through references to the news and current events.

One of Kawada’s tanka, for example, depicts a vivid scene of the poet reading the imperial rescript, possibly aloud:

嚴肅にいくさ宣らすみことのり独り座りて吾が捧げ讀む50

|

|

In this tanka, Kawada performs what he sees as an appropriate response to receiving the Imperial Edict. He sits alone and reads it reverently, transforming the act of reading the Emperor’s words into something more akin to prayer.

Another Yoshii Isamu poem moves from reverence to melodrama:

大詔いまか下りぬみたみわれ感極まりて泣くべくおもほゆ51

|

|

This poem stresses the role of all Japanese as the Emperor’s subjects, weeping en masse upon receiving the declaration of war. The sense is not simply overwhelming relief. The use of mitami ware (“we, who are Your people”), a phrase used in the Man’yōshū, suggests a filial piety reaching back in time, with tears portrayed as the proper sign of gratitude to the time-honored Father of Japan’s family-state.

大勅語捧げまつればおのづから心のふる手に及ぶかも52

|

|

|

Onoe Saishū |

In this tanka, Onoe Saishū has a rare experience for a calligrapher like himself: his hands start to shake. Upon receiving the declaration of war (here rendered dai chokugo), both hands and heart tremble with emotion. In a different context this might be taken as an expression of fear. But in “humbly receiving” (sasage matsureba, two extremely reverential verbs) the imperial rescript, Onoe emphasizes his fervent encounter with the words of a living god.

Men of letters employed this theme of deep emotion across all genres of literature, from prose essays to free verse, diaries, and short stories. Whereas tanka in particular focused on the emotional response to reading the Imperial Edict in the newspaper or hearing it on the radio, other forms of poetry evoked the popular response in a more accessible way. Consider, finally, popular Symbolist free verse poet Itō Shizuo’s (1906–1953) “Imperial Edict” (Ōmikotonori). Combining collective relief at the decision to wage war against America and Britain with a touching awareness of a new unity of purpose, this short poem epitomizes how poetry could serve as propaganda for Japan’s war.

|

|

Conclusion

The first six months after December 8, 1941 witnessed a carnivalesque atmosphere in Japan.54 The rapid advance of Japanese forces across Asia created a sense of destiny and unbridled optimism on the home front. An interested public looked with delight upon success after success, as the Japanese military seized control over Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaya, the Netherlands Indies, Burma and the Philippines. By February 1942 writer Kamiya Shigeru had noted the advent in Japan of what he called the “spirit of December 8th,” an unprecedented sense of self-confidence and faith in Japan’s mission. “Today even small children,” he wrote, “stand before a world map dreaming dreams of advance after advance, thinking ‘here too, here too!’”55

Poets championed this “spirit of December 8th.” Literary figures at the height of their power crafted works dense with hurt, vengeance, gratitude, and reverence. They performed deeply emotional responses to war through their tanka. In the process, they served as models for other Japanese subjects to accept the declaration of war not with anxiety or doubt but with tears in their eyes, and with hearts and hands trembling in excitement. Something both delicate and disturbing is captured here within the tanka’s rigid frame. The “spirit of December 8th” that these poets epitomized was a firm conviction in Japan’s victimization, in the necessity for retribution, in an assured and anointed victory, but also in the glory of inevitable death.

These poets were the perfect propagandists. Most of them were between the ages of 54 and 65 at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor. They had been brought up through Japan’s statist and nationalistic education system, which stressed loyalty and self-sacrifice in the service of the Emperor. During their formative years, they had watched the waves of nationalist excitement that accompanied Japan’s first modern wars (the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05) and the rise to great power status. And by the 1930s, many of them had participated in both physical and “spiritual mobilization” for war. Saitō was a former general in the Imperial Japanese Army and an ultranationalist who spent time in prison for his role in the February 26th Incident of 1936, a failed coup d’état by young officers. Kitahara by 1938 had begun to publish highly nationalistic works, including the lyrics for Banzai Hitler Youth. And Kawada was a self-avowed nationalist and the most prolific writer of tanka and patriotic verse during World War II. Their collective histories, their experiences of Japan’s rise, and their status as the premier poets of the day made them unique advocates of the imperial nation’s cause.

Conversely, Ozaki Yukio and Nanbara Shigeru epitomize what might be thought of as a spirit of private dissent. Pro-war poets, upon receiving the imperial rescript, exhorted their fellow countrymen to prepare for glorious death on the battlefield and the homefront. Ozaki and Nanbara, however, had an audience of one. In secreting away their tanka in the pages of their personal diaries, they secured a private space to express doubt, sorrow, anxiety and hopelessness. In the process, they embodied what many across Japan may have felt but could not say: that their country had launched a foolhardy and suicidal act.

Tanka mark time. They are composed every New Year’s Day, at significant life events, and to commemorate the momentous. December 8, 1941 looms large in the modern history of Japan and the world, and it fittingly cast a long tanka shadow. To look at these works, 75 years later, brings their own time a little closer.

The work described in this paper was partially supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. CUHK 24610615).

|

Notes

The Manchurian Incident of September 1931 and the China Incident of July 1937 also led to popular enthusiasm and war fever. But the attack on the United States and Great Britain in December 1941 led to an outpouring of poetry, short stories, scholarship, essays, and overall support that perhaps exceeded these earlier events. Magazines like Bungei shunjū, Chūō kōron (Central Review), Shin joen (New Woman’s Garden), Shinchō (New Tide), and others even published diaries about people’s daily lives and emotional states on December 8, when they heard the news of Japan’s new war.

In our transliterations, we made the decision to split each tanka into five lines according to syllable count. Where possible, we made each of those lines in their English renderings also 5-7-5-7-7, except when the original also diverged from this pattern or where poetic license dictated a shorter poem. While tanka (and haiku) tend to be printed in one line without spaces when published in Japanese, splitting up the lineation into five lines (or three, in the case of haiku) is conventional for many English translations of these works. Our decision to make English translations conform to this particular syllabic count, however, is not entirely the norm in translations of tanka. The Japanese mora (syllables) counted in tanka and haiku are different and often shorter linguistic units than English syllables, and so these poetic forms in Japanese contain less information than their English syllabic equivalents. This leads translations like ours to be wordier than the originals. We thought, however, in the case of these poems, that this kind of translation had several benefits. The first was to make the Japanese tanka into English tanka; there is already a long tradition of tanka and haiku written originally in English, with lines of five and seven syllables, and they comprise an established, recognizable and popular poetic genre. Our translations also emphasize that all these poets were working within the constraints of the same rigid form. Another useful side-effect of this decision was the flexibility it afforded us to make certain implications more explicit, and to add brief explanations of terms or concepts within the poems when necessary without always relying on glosses or subsequent commentary. This is important when a reference would be instantly understood by the average reader in Japan at the time, and leaving it overly opaque in the English translation would give an inaccurate impression of a similar opacity in the original.

An important exception is Donald Keene’s work, but he focuses much less on poets than on fiction writers. And his work on tanka neglects the ways in which poetry was used to express opposition to war. See Donald Keene, “Japanese Writers and the Greater East Asia War,” The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 23, No. 2 (Feb. 1964), 209-225; Donald Keene, “The Barren Years: Japanese War Literature, Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Spring 1978), 67-112; and Donald Keene, Sakka no nikki o yomu Nihonjin no sensō (Tokyo: Bungei Shunjū, 2009).

On December 8, Konoe went to the Peers Club in Tokyo and was unusually despondent, in stark contrast to the popular excitement among Japan’s nobility. He told his aide and son-in-law, Hosokawa Morisada, “It is a terrible thing that has happened. I know that a tragic defeat awaits us at the end. I can feel it. Our luck will not last more than two or three months at best.” For Konoe’s views, see Yabe Teiji, Konoe Fumimaro, Vol. 2 (Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1952), 467; Yoshitake Oka, Konoe Fumimaro: A Political Biography (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1983), 161. On December 8, Matsuoka lamented his own role in the outbreak of war from his sickbed at home, telling an aide that signing the Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy “was the biggest mistake of my lifetime … When I think of this, it will bother me even after I die.” Quoted in Jeremy A. Yellen, “Into the Tiger’s Den: Japan and the Tripartite Pact, 1940,” Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 51, No. 3 (Jul. 2016), 576.

Higashikuni Naruhiko, Higashikuni nikki: Nihon gekidōki no hiroku (Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten, 1968), 103.

In the original tanka, there is a marked contrast between kishō, “unexpected victory,” and kika, “unexpected defeat.” Within the constraints of the poem, however, we thought it more important to emphasize Nobunaga’s arrogance [ogori]. This necessitated leaving these parallel terms, which would have been much wordier in English, less apparent. The second line could also be translated (in seven syllables) as “Pride in his chance triumph at” Okehazama.

Douglas H. Mendel, Jr., “Ozaki Yukio: Political Conscience of Modern Japan,” The Far Eastern Quarterly, Vol. 15, No. 3 (May 1956), 343.

Nanbara Shigeru, Keisō: kashū (Tokyo: Sōgensha, 1948). See also Andrew E. Barshay, State and Intellectual in Imperial Japan: The Public Man in Crisis (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 109-113.

Nanbara, Keisō, 173. For separate translations, see Barshay, State and Intellectual, 111; see also Nambara Shigeru, War and Conscience in Japan: Nambara Shigeru and the Pacific War, ed. and trans. by Richard H. Minear (Rowman & Littlefield, 2010). 117.

Ibid., 173. Separate translations can be found in Barshay, State and Intellectual, 111; Nambara, War and Conscience, 117.

Leith Morton provides an excellent analysis of wartime tanka poetry. See Leith Morton, “Wartime Tanka Poetry: Writing in Extremis,” in Recentering Asia: Histories, Encounters, Identities (Global Oriental: Leiden, Netherlands; Boston, 2011), 256–284.

See Nambara Shigeru and Richard Minear, “Nambara Shigeru (1889-1974) and the Student-Dead of a War He Opposed,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol. 9, Issue 4, No. 1, January 24, 2011 (Accessed Oct. 31, 2016). See also Nambara, War and Conscience in Japan.

The classic study on this phenomenon is Hugh Byas, Government by Assassination (New York: A.A. Knopf, 1942).

For more on thought control, see Richard H. Mitchell, Thought Control in Prewar Japan (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1976).

For more on the subversiveness of Christianity, see Mark R. Mullins, “Ideology and Utopianism in Wartime Japan: An Essay on the Subversiveness of Christian Eschatology,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, Vol. 21, No. 2-3 (1994), 261-80.

It is difficult to find accurate figures on print circulation. That said, according to Yamazaki Yasuo, Bungei shunjū in 1940 had a print circulation of 200,000 copies. See Yamazaki Yasuo, Nihon zasshi monogatari (Tokyo: Ajia Shuppansha, 1959), 305. Bungei shunjū would be temporarily shut down by Occupation authorities in March 1946 owing to its consistent support for Japan’s war.

The tanka poets we consider here were all men. This owes to a simple fact: the world of tanka was highly conservative and men dominated the ranks of the top tanka poets. Popular female poets like Yosano Akiko were the exception. Incidentally, Yosano, too, would come to support Japan’s war. For an account of hershiftfrom prominent anti-war writer in the early 1900s to her later days promoting the colonial project in Manchuria in the 1930s, and finally to her pro-war yet melancholic tanka after Pearl Harbor, seeSteve Rabson, “Yosano Akiko on War: To Give One’s Life or Not—A Question of Which War,”Journal of the Association of Teachers of Japanese, Vol. 25, No. 1 (1991), 45-74.

There was much to draw on. The rejection of the Japanese delegation’s proposed racial equality clause at Versailles in 1919 and the so-called Japanese Exclusion Act of 1924 which barred Japanese immigration to the US served as constant reminders of the low regard for which Japan was held within the international system.

The English translation of the imperial rescript is taken from Japan Times & Advertiser, evening edition, December 8, 1941, 1. For the original Japanese-language document, see Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), reference code: A03022539800.

For more on uchiteshi yamamu, see David C. Earhart, Certain Victory: Images of World War II in the Japanese Media (Routledge, 2015), 309-32.

According to Donald Keene, this group “attack[ed] such varying targets as ‘art for art’s sake,’ freedom, Communism, and individualism. See Keene, “Japanese Writers and the Greater East Asia War,” 213.

The Japanese version was taken from Donald Keene, Sakka no nikki o yomu Nihonjin no sensō, 28-29. We are also making use of Keene’s wonderful translation, found in Keene, “Japanese Writers and the Greater East Asia War,” 213.

Negotiations toward an understanding with the United States began in March 1941, and for all intents and purposes ended with the Hull Note on November 26.

A poem by an American soldier, Fremont Sawade, stationed at Honolulu at the time of the attacks, brings up many of the same themes from the other side: of America’s victimization, the necessity of vengeance against Japan, and of the day of Pearl Harbor as one that will go down in history. John Wilkens, “Poem captured surprise, horror of Pearl Harbor,” The San Diego Union-Tribute, June 16, 2012. http://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sdut-a-poet-once-for-all-time-2012jun16-htmlstory.html (accessed Oct. 24, 2016).

Takamura Kōtarō, “Jūnigatsu yōka,” Takamura Kōtarō zenshū, Vol. 5 (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1994) 50-51.

See Louise Young, Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 106-113.

Hiroaki Sato, “Gyokusai or ‘Shattering like a Jewel’: Reflection on the Pacific War,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 6, Issue 2 (Feb. 1, 2008). See http://apjjf.org/-Hiroaki-Sato/2662/article.html (accessed on Oct. 24, 2016).

Gunjishi Gakkai, Daihon’ei rikugunbu sensō shidōhan kimitsu sensō nisshi, Vol. 2 (Tokyo: Kinseisha, 1999), 550.

Of course, it is possible to read resistance into this and other poems in the Bungei shunjū collection owing to the ambiguity of the language. But it would be misguided to do so. The tanka poets considered here were typical in that they wrote poems meant to express support for Japan’s war for Asia.

Kawada Jun’s two volumes, Shika Taiheyō sen (Historical Tanka from the Pacific War) and Shika nettai sakusen (Historical Tanka from the War in the Tropics) were both released in 1942. His wartime tanka are considered in depth by Leith Morton in “Wartime Tanka Poetry,” 262–269.

Poet Takamura Kōtarō, for instance, wrote that December 8th “was a date to be remembered, one truly full of deep emotion” (jitsu ni kangeki ni michita kinen subeki hi to natta). See Takamura Kōtarō, “Jūnigatsu yōka no ki,” Chūō kōron, Vol. 57, No. 1 (Jan. 1942), 110.

Several passages of this essay appear in translation in Leith Morton, “Wartime Tanka Poetry,” 267–268. Original essay first published in Kawada Jun, Shika nanboku sakusen (Tokyo: Kotori Shorin, 1943), 135-40.

Donald Keene notes that this “festive mood” (omatsuri kibun) continued for one year after the attack on Pearl Harbor. See Keene, Sakka no nikki o yomu Nihonjin no sensō, 40.