The following article is a reprint of a unit developed by MIT Visualizing Cultures, a project focused on image-driven scholarship. Click here to view the essay in its original, visually-rich layout. In the coming months the Asia-Pacific Journal will reprint a number of articles on the theme of social protest in Japan originally posted at MIT VC, together with an introduction by John W. Dower to the series. These are the first in a continuing series of collaborations between APJ and VC designed to highlight the visual possibilities of the historical and contemporary Asia-Pacific, particularly for classroom applications.

Between 2002 and 2013, the Visualizing Cultures (VC) project at M.I.T. produced a number of “image-driven” online units addressing Japan and China in the modern world. Co-directed by John Dower and Shigeru Miyagawa, VC tapped a wide range of hitherto largely inaccessible visual resources of an historical nature. Each topical treatment—which can run from one to as many as four separate units—formats and analyzes these graphics in ways that, ideally, open new windows of understanding for scholars, teachers, and students. VC endorses the “creative commons” ideal, meaning that everything on the site, including all images, can be downloaded and reproduced for educational (but not commercial) uses.

Funding and staffing for VC formally ended in 2013, with around eight topical treatments still in the pipes. These will eventually go online. Overall, including the treatments to come, the project includes a total of fifty-five individual units covering twenty-six different subjects. The China-Japan division will be roughly equitable when everything is in place. (There will also be a two-part treatment of the U.S. and the Philippines between 1898 and 1912.) The full VC menu can be accessed at visualizingcultures.mit.edu.

VC is closing shop for the production of new units at a moment when it was just reaching a “critical mass” of subjects that invite crisscrossing among separate topical treatments. Western imperialist expansion beginning with the Canton trade system, first Opium War, and Commodore Matthew Perry’s “opening” of Japan is potentially one such subject; comparing and contrasting Japanese and Chinese engagements with “the West” is another. The VC units draw vivid attention to political, cultural, and technological transformation in East Asia between the mid-19th and mid-20th century. Many of them highlight graphic expressions of militarism, nationalism, racism, and anti-foreignism. Because the visual resources tapped for these units range from high art to popular culture, and are especially strong in the latter, it is now possible to tap the site to explore the emergence of consumer cultures and mass audiences in Japan and China. This, in turn, calls attention to popular cultures and grassroots activities in general.

One example of the insights to be gained by approaching the VC menu with this comparative perspective in mind is the subject of popular protest in Japan. That is the common thrust of the four separate VC units introduced here. This is, of course, a pertinent subject today, when the mass media in the Anglophone world tends to portray Japan as a fundamentally homogeneous, consensual, harmonious, conflict-averse and risk-averse “culture” (a familiar rendering, for example, in the venerable New York Times).

No serious historian of modern Japan would endorse these canards, which carry echoes of the “beautiful customs” nostrums of Japan’s own nationalistic ideologues. At the same time, however, it cannot be denied that the past four decades or so have seen nothing comparable in intensity or scale to the popular protests in prewar Japan, or the demonstrations and “citizens’ movements” (shimin undō) that took place in postwar Japan up to the early 1970s. How can we place all this in perspective?

The image-driven VC explorations of protest in Japan begin in 1905 and end with the massive “Ampō” demonstrations against revision of the U.S.-Japan mutual security treaty in 1960. The four treatments that will be reproduced in The Asia-Pacific Journal beginning in this issue are as follows:

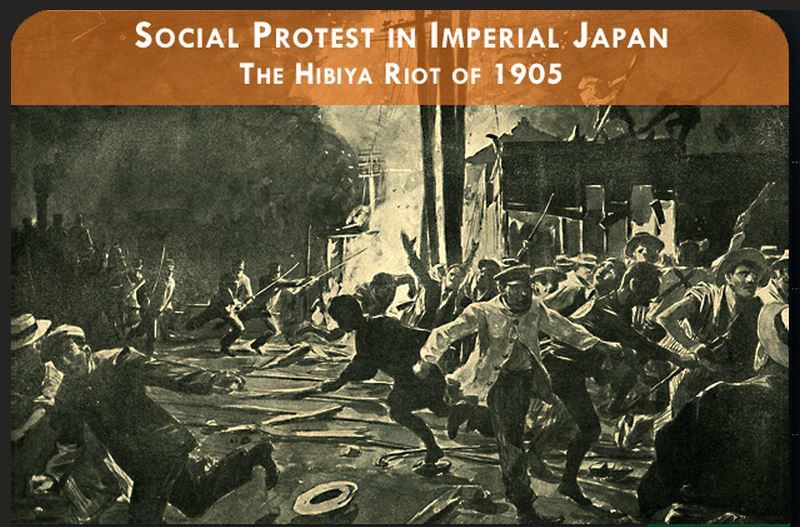

1. Social Protest in Imperial Japan: The Hibiya Riot of 1905, by Andrew Gordon. We reprint this article with this introduction. Other articles will follow in the coming months.

2. Political Protest in Interwar Japan: Posters & Handbills from the Ohara Collection (1920s~1930s), by Christopher Gerteis (in two units).

3. Protest Art in 1950s Japan: The Forgotten Reportage Painters, by Linda Hoaglund.

4. Tokyo 1960: Days of Rage & Grief: Hamaya Hiroshi’s Photos of the Anti-Security-Treaty Protests, by Justin Jesty.

VC and the Asia-Pacific Journal are committed to bringing the highest quality visual images to the classroom. In establishing this partnership, we anticipate publishing the subsequent units on protest every two weeks. We hope to follow this up with new units in preparation and projected.

John W. Dower is emeritus professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His books include Empire and Aftermath: Yoshida Shigeru and the Japanese Experience, 1878-1954 (1979); War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1986); Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (1999); Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor / Hiroshima / 9-11 / Iraq (2010); and two collections of essays: Japan in War and Peace: Selected Essays (1994), and Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering: Japan in the Modern World (2012).

|

On September 5, 1905, a massive three-day riot erupted in Tokyo protesting the disappointing terms of the peace treaty that ended the Russo-Japanese War. A decade earlier, after emerging victorious in the Sino-Japanese War, Japan had demanded and received a huge indemnity from defeated China. Although the war with Russia was far more costly in casualties and money, both sides were exhausted by 1905 and Japan was in no position to demand an indemnity from Russia. Because the Japanese public had been bombarded with reports of victory after victory, expectations of a profitable peace settlement were high and the outrage when this did not materialize was enormous.

Almost three-quarters of the police boxes throughout the capital city were destroyed, buildings and streetcars were torched, and some 450 policemen and 50 firemen were injured in addition to many of the protesters. The government responded by declaring martial law. It almost seemed as if the war had come home.

The anti-treaty riot—commonly called the Hibiya Riot after the park where the demonstrations began—marked the first major social protest of the age of “imperial democracy” in Japan that began with the promulgation of the Meiji constitution in 1890 and extended into the early 1930s.

This unit focuses in detail on the visual record of this spontaneous anti-government demonstration as presented in The Tokyo Riot Graphic, an extraordinary special issue of an illustrated magazine that was published at the time and featured both photographs and artistic renderings of the unfolding violence.

MAKING NEWS GRAPHIC

The founding father of illustrated newspapers and magazines worldwide was the Illustrated London News, first published in 1842 and immediately flattered by imitators throughout the West: the Leipziger Illustrirte Zeitung in Germany and L’illustration in France (both founded in 1843); and, a bit later, Harper’s Monthly (1850) and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (1855) in the United States. The owner and publisher of Tokyo Riot Graphic was Yano Fumio (1851–1931, also known by the pen name of Yano Ryūkei). Yano was a well known writer and political activist. He first encountered these publications, in particular the Illustrated London News and a more-recent British competitor simply titled The Graphic, while visiting England in 1884. We do not know which issues he read. But coverage of the British empire and its military engagements was a staple element of the graphic genre, and one which very likely caught his attention. Yano decided Japan both sorely lacked and very much needed publications of comparable content and quality, and he eventually undertook to address this need himself. 1

Yano launched his venture with the title Oriental Graphic (Tōyō Gahō) in 1903. Later that year he renamed the magazine Recent Events Graphic (Kinji Gahō) and similarly named his publishing venture the Kinji Gahō Company. With the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in February 1904, Yano and his trusted chief editor, the well-known writer Kunikida Doppo, correctly decided that the public wanted a steady diet of wartime pictures and text. To signal their commitment to war news and images from cover to cover, with publication of the February 18 issue they re-titled the magazine The Wartime Graphic (Senji Gahō). Starting with the fourth issue under this new name (March 20, 1904), Yano and Kunikida added the English title The Japanese Graphic to the cover and English-language captions to the illustrations.

These naming innovations signaled the twin aims of offering a Japanese record of the war to an international audience and distinguishing theirs as the definitive record among several competing wartime graphic serials. Through October 1905, including nine special issues, Yano and Kunikida put out 68 numbers with this title, a rate of more than three issues per month with print runs of around 50,000 copies, before turning the magazine’s title back to the more generic Recent Events Graphic. The Russo-Japanese War not only provided the spark that set off the fire of imperial democratic protest. It brought into being the publications that captured and helped define this event in its own time and for posterity, and it published images of the war that shaped the visual record of the socially turbulent “peace” that followed.

As with the Illustrated London News and its followers in the West, the graphic genre in Japan included text in the form of articles on politics, war, and society, but it was most notable for its numerous illustrations. The earliest such periodicals in the West primarily featured drawings carved into wooden blocks through the technique of end-grain wood engraving. 2 Early photographs likewise had to be engraved into wooden blocks in order to be reproduced in newspapers or magazines. Over the course of the 19th century, new technologies (lithography and half-tone printing) allowed the transfer of photographs and hand-drawn illustrations to a printed page without need for hand engraving, although in both the West and Japan some artists and publishers continued to make use of woodblock prints. The Wartime Graphic, including the special riot issue, featured a wide array of image techniques: multi-color lithography (and in some cases possibly woodblock prints) for its striking covers, half-tone printing of both photographs and hand drawn art (primarily watercolors and pencil sketches), and woodblock prints inserted into narrative text.

The Wartime Graphic: selected covers

|

||

| May 20, 1904 | July 10, 1904 | Dec 10, 1904 |

|

||

| Dec 20, 1904 | Mar 10, 1905 | April 20, 1905 |

|

||

| June 20, 1905 | July 1, 1905 | Aug 10, 1905 |

As one can see from this sampling, the covers of The Wartime Graphic are remarkable for the sophistication of the artwork and the variety of themes and moods. One of course finds some covers with a nationalistic and martial aspect, such as that of May 20, 1904 celebrating soldiers rushing into battle. But one also finds relatively calm scenes, such as that of the soldiers in the woods (December 20, 1904) and even some suggesting the Japanese are carriers of peace (through war), such as the cover showing a dove being released from a naval ship (July 10, 1904). Also noteworthy are scenes from the homefront, including a marvelous depiction of lanterns carried in a victory parade (July 1, 1905), and a cover highlighting the surging popularity of postcards as a new means of communication (March 10, 1905). The cover invoking the figure of the Sun Goddess (Dec 10, 1904) and that depicting US-Japan friendship (Aug 10, 1905) are also of interest. This cover appeared just as the peace-treaty negotiations were being concluded in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and it specifically commemorated the visit to Japan of a major diplomatic mission led by the American secretary of war, William Howard Taft, and including President Roosevelt’s famous daughter, Alice.

While Yano and Kunikida were certainly pioneers of this genre in Japan, they were not in fact the first to produce illustrated newspapers or magazines in Japan along the lines of European or American predecessors. That honor belongs to the Fūzoku Gahō (Customs Graphic), founded in 1889. This fascinating publication featured illustrations on culture and customs of elites and ordinary folk alike. It was particularly concerned to contrast the daily life of the Japanese past with new modes of dress or deportment of Western origin. During the Sino-Japanese War (1894 to 1895) an illustrated monthly True Record of the Sino-Japanese War (Nisshin sensō jikki) was one of the first periodicals to feature significant numbers of half-tone photographs. The Customs Graphic also celebrated this war with a fancifully rendered battle scene on one of its covers, but it otherwise showed little concern for matters political; the True Record was published only once a month, with relatively stale photographs of ships and landscapes, or portraits of generals and admirals.

Compared to these earlier efforts, the graphic publications from the time of the Russo-Japanese War were unprecedented in the visual force of their illustrations as well as their popularity and circulation. Hiratsuka Atsushi, an assistant to Kunikida from the founding of Oriental Graphic in 1903, recalled in a 1908 memorial essay about the great writer that the magazine’s sales took off when it began to run illustrations sent by artists dispatched by Kunikida to Korea in early 1904. Hiratsuka gives literal meaning to the cliché “hot off the presses” as he describes the frenzy of efforts to meet reader demand: “On one occasion, the printer couldn’t keep up and it is even said that the [printing] machinery caught fire.” 3

In addition to such publications modeled on Western periodicals, one found in 19th-century Japan a vibrant and evolving indigenous tradition of woodblock-print broadsheets. Combining image and text, and focused on newsworthy incidents, the earliest of these coincidentally began to appear around the same time as the earliest publications of illustrated news in the West. Called kawaraban and circulated in spite of prohibitions issued by the Tokugawa authorities, they flourished in the early-19th century. After the Meiji Restoration, a now legal—if closely monitored—genre of broadsheet prints soared in popularity, especially during the Satsuma rebellion. Known as nishiki-e, these were single-page sheets featuring a traditionally produced woodblock print in vibrant color and a short explanatory text, usually taken from a recent newspaper article.

The woodblock prints of the Sino-Japanese War analyzed by John Dower in Throwing Off Asia ll were an outgrowth of these widely circulated “news” prints. At the time of the Sino-Japanese War, as Dower describes, they played a key role in conveying images and understandings of the war to people in Japan. But as Dower notes in Throwing Off Asia lll, the situation was quite different a decade later. Although woodblock prints during the Russo-Japanese War did offer some powerful images, many of the prints merely imitated those of the Sino-Japanese War.

During Japan’s second imperialist war, the illustrated periodical press was a source of greater creative energy than individual prints, and it found its way to a far larger reading and viewing audience. Its repertoire of images owed a debt both to the illustrated genre of the modernizing West and to this evolving indigenous practice of woodblock prints of current events. Some of the new graphic publications of the Russo-Japanese War were short-lived commercial failures, but others, prominently including The Japanese Graphic, were both popular and profitable. They featured art work of high quality produced by some of Japan’s most talented young artists. Leading contributors to The Japanese Graphic during and after the war included Koyama Shōtarō, one of the most important early teachers of Western art in Japan, and the most promising students of his Fudōsha Academy.

Whereas 2,000 to 5,000 copies might have been made of a traditional woodblock print of this era, each issue of The Japanese Graphic (and its competitors) boasted print runs of 40,000 to 50,000 copies, offering from 20 to 50 photographs and illustrations of varied sizes and types per issue. In numbers and in visual impact, these illustrated publications were the most important sources to imprint the war and its aftermath in Japanese popular imagination. Particularly significant was the hand-drawn art, both watercolor paintings and woodblock sketches, better able than the photographs of that era to convey motion and mood. While the history of politics in imperial Japan, including the story of social protest, has been much studied by historians writing in English as well as in Japanese, the visual record produced by illustrated journalism offers insights not easily gained from textual sources into a number of themes. These images make it clear that imperialism was not simply a top-down imposition of the government, but a co-production with active participation by the commercial media and its customers. They also show that even as masses of people embraced the cause of empire, they added to it their own desire for democracy.

The War at Home

The Russo-Japanese War ended with a stalemate on the battlefield. Both sides were exhausted and depleted. Japanese forces suffered roughly 80,000 fatalities (over 20,000 of them from disease), compared to some 17,000 (almost 12,000 from disease) in the Sino-Japanese War a decade earlier. The total cost of the war in yen came to 1.7 billion yen, eight times the cost of the Sino-Japanese War. To pay these bills, the government had borrowed aggressively on the London bond market and had imposed all manner of new or increased taxes at home: sales taxes on cooking oil, sugar, salt, soy sauce, sake, tobacco, and wool; and a transportation tax that raised the cost of riding on the new streetcars of the capital by 33 percent. Faced with the prospect of even greater costs if the war continued, Japanese negotiators were willing to settle for less than they desired or had implicitly promised to the home-front populace.

In the peace treaty negotiated at Portsmouth, New Hampshire through the mediation of American president Theodore Roosevelt, Japan did win a free hand to dominate Korea as a protectorate, and it gained the upper hand in Southern Manchuria in the form of a leasehold that formed the basis for the Southern Manchuria Railway, protected by troops that developed into the Kwantung Army. It also took possession of the territory of southern Sakhalin. But it gained no reparations which might have offset the war’s cost. The leasehold was a form of imperialist encroachment, to be sure, but not an outright colony, and Sakhalin was a barren place of little strategic or economic value. In contrast, the Sino-Japanese War of a decade before had brought both a massive indemnity and full control of the island of Formosa (Taiwan), which became a Japanese colony.

Map of Tokyo in 1905. Source: Andrew Gordon, Labor and Imperial Democracy in Prewar Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991) |

It is not surprising in this context that a coalition of journalists, university professors, and politicians in the Japanese diet (parliament) who had vociferously supported the war now came together to protest the peace. They turned to the urban populace for support, calling a rally in Hibiya Park on September 5. The Tokyo police—an arm of the national government administered through the powerful Home Ministry—forbad the gathering. But a crowd estimated to number around 30,000 overran the barriers and rushed into the park. A brief rally ensued, about 30 minutes in all.

Later that day, a second large crowd gathered in front of the Shintomiza theater to hear speeches denouncing the treaty.

As the attendees spilled out from the initial rally in the park, Kōno Hironaka, a popular and hawkish political veteran and head of the alliance which had organized the event, led a crowd of perhaps 2,000 on a march toward the imperial palace. Others in the crowd fought with police, and the violence began to spread. Groups of dozens or hundreds attacked police and government buildings, offices of a pro-government newspaper (Kokumin shinbun), and streetcars and the offices of the streetcar company.

Source: Andrew Gordon, Labor and Imperial Democracy in Prewar Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991)

These actions continued for three days, during which time Tokyo lacked any effective forces of order. By the time the riot ended, 17 people had been killed and 311 arrested in clashes with police or the military troops eventually sent to subdue the rioters. 70 percent of the city’s police boxes (small two-man substations located in neighborhoods through the city) were destroyed along with 15 streetcars. Smaller riots broke out in Yokohama and Kobe. Anti-treaty rallies took place nationwide. 4

This outburst of riot and protest was the first of nine such incidents in Tokyo that took place through 1918 and were sparked by related discontents (see table, below). The illustrated record of the anti-treaty riot, discussed in the chapters to follow, teaches us much about the themes marking not only that event, but those that followed as well.

|

Sept. 5-7, 1905 |

Against treaty ending the Russo-Japanese War |

Against clique government; for “constitutional government” |

Hibiya Park |

17 killed; 70 percent of police boxes, 15 streetcars destroyed; progovernment newspapers attacked; 311 arrested; violence in Kobe, Yokohama; rallies nationwide |

|

Mar. 15-18, 1906 |

Against streetcar-fare increase |

Against “unconstitutional” behavior of bureaucracy, Seiyūkai |

Hibiya Park |

Several dozen streetcars smashed; attacks on streetcar company offices; many arrested; increase revoked |

|

Sept. 5-8, 1906 |

Against streetcar-fare increase |

Against “unconstitutional” actions |

Hibiya Park |

113 arrested, scores injured; scores of streetcars damaged; police boxes destroyed |

|

Feb. 11, 1908 |

Against tax increase |

|

Hibiya Park |

21 arrested; 11 streetcars stoned |

|

Feb. 10, 1913 |

For constitutional government |

Against clique government |

Outside Diet |

38 police boxes smashed; government newspapers attacked; several killed; 168 injured (110 police); 253 arrested; violence in Kobe, Osaka, Hiroshima, Kyoto |

|

Sept. 7, 1913 |

For strong China policy |

|

Hibiya Park |

Police stoned; Foreign Ministry stormed; representatives enter Foreign Ministry to negotiate |

|

Feb. 10-12, 1914 |

Against naval corruption For constitutional government |

Against business tax For strong China policy |

Outside Diet |

Dietmen attacked; Diet, newspapers stormed; streetcars, police boxes smashed; 435 arrested; violence in Osaka |

|

Feb. 11, 1918 |

For universal suffrage |

|

Ueno Park |

Police clash with demonstrators; 19 arrested |

|

Aug. 13-16, 1918 |

Against high rice prices |

Against Terauchi Cabinet |

Hibiya Park |

Rice seized; numerous stores smashed; 578 arrested; incidents nationwide |

CHALLENGING THE STATE

In 1873, Fukuzawa Yukichi observed in one of his most famous books, An Outline of Civilization, that “Japan has a government but no nation.” The Japanese people, that is, had no sense of themselves as kokumin. This was a neologism that Fukuzawa—the most important intellectual of his day and a brilliant wordsmith—defined in this text by inserting the phonetic Japanese pronunciation of “nation” (nēshon) alongside the characters for kokumin.

By the time of the Hibiya Riot, these once parochial or apolitical people, or their children, showed themselves to be active members of the nation and supporters of empire. They were anxious to voice their opinions on matters of foreign and domestic policy and insistent they be respected. Much of the apparatus of the modern nation had initially been imposed on them from on high, including mass compulsory education and a military draft in the 1870s. The Meiji constitution was written in secret and promulgated in 1889 as a gift of the emperor to his loyal subjects. The state promulgated a new civil code nationwide in the 1890s.

In all these steps, the balance between the obligations and the rights of the people tilted clearly toward the duties of subjects to be loyal to the state. Hibiya Park itself was designed and built by the government on a Western model at the turn of the century, with the understanding that modern cities required grand public spaces. It opened in 1903, just two years before the riot. It was first given extensive use during the Russo-Japanese War to celebrate war victories. The project of nation building was in these ways undertaken by the state with the intention of bringing into being a loyal body of kokumin, or people of the new nation. As Japan established itself as an imperial power in the decade spanning the turn of the 20th century, this project seemed to be working more or less as its elite architects had intended.

The irony made clear in the course of the riot was that the Meiji state if anything had succeeded too well. In matters political the people had views of their own, which they were more than willing to express in word and deed. They took various steps to appropriate public and imperial spaces, captured in some cases uniquely in the pages of The Tokyo Riot Graphic. In their anger at being excluded, the crowd asserted that Hibiya Park belonged to the people, not the state. This stance is dramatically rendered in a drawing of a stone-throwing melee at the entrance to the park “which followed in consequence of the attempt of the police to prevent the ingress of the crowd into Hibiya Park.” The perspective of this illustration—sketched from the side of what the caption writer in the Japanese language caption termed “Tokyo citizens” as they confronted the state’s forces or order—suggests that the artist supported the people’s claim to the park.

Among the most unusual depictions of such acts of appropriation are two photographs of remarkably calm moments at key places during the three days of the riot. We can be thankful and impressed that the photographer found these scenes worthy of recording and that editor Kunikida found them worthy of publishing.

Hot-air balloons trail banners denouncing the emperor’s advisors and asserting the shared will of the people and their sovereign. |

The first photo, as the English caption tells us, shows “citizens angling in Ichigaya moat, where it is usually prohibited.” The Ichigaya moat was (and to this day remains) a remnant of the outer moat surrounding what was once the shogun’s castle at the center of Edo, which by 1905 had for several decades been the imperial palace, home to the Meiji emperor. These anglers were on one level innocently pursuing their hobby in a convenient and suddenly available location. But many or most of them surely understood the moat’s special place in the city. They were staking an implicit claim to share in the use of normally forbidden imperial space.

The second photo shows “citizens sleeping on the turf in Hibiya Park,” a behavior not usually allowed according to the Japanese language caption. While napping or reading, were they not also extending a claim on behalf of ordinary people to occupy public space at the city’s center? Over time, this claim took root. In September 1913 on the occasion of a much smaller riot, also provoked by perceived weakness in Japanese foreign policy (this time toward China), the Asahi newspaper noted that “Hibiya Park is by now synonymous with the people’s rally.” 5

Much more explicitly, one of the woodcut prints which accompanied Yano Ryūkei’s narrative account of the riot reveals a popular conception of shared sovereignty presented to the crowd with considerable effort and cost. Although police closed the park to the anti-treaty protesters, organizers of the rally nonetheless managed to raise large banners with hot air balloons in the vicinity of their planned event. The banner on the right read—in a difficult four character Chinese-style slogan—that “in tears we protest what the emperor’s advisors have done.” The other banner pledged in Japanese prose that “we hold the sword of rectification.”

Here we see the rally organizers putting forward a vision in which the wishes of the emperor and the people were assumed to mesh, and be obstructed by his wrong-headed advisors. The duty of the people was to rectify the situation by enforcing this shared will of people and ruler. Testimony at the trial of those arrested for rioting also speaks of four-character banners carried by protesters, and describes as well the scene where the crowd led by Kōno Hironaka sought to carry black-trimmed flags toward the imperial palace, in essence offering condolences to the emperor for the bad policies of his officials. A policeman tried to stop them. They threw stones and beat him, shouting “this is not something the police should restrict.” 6

These actions—and their depiction—anticipated by over a decade the concept famously articulated by the political thinker Yoshino Sakuzō that in Japan sovereignty was rooted in both the monarch and the people (minponshugi). Like the ministers they criticized, people in the crowd supported empire and emperor. These commitments had been fostered from above through schools and through public rituals honoring the emperor, such as the reading aloud of the imperial rescript on education in school ceremonies. But the protesters not only disagreed with government policies. They claimed both duty and the right to challenge the state bureaucracy. They made Hibiya Park a symbol of their freedom to gather and express the shared will of the people and the monarch, which a legitimate government should respect.

IDENTIFYING THE “PEOPLE”

Who were these rioters or protestors? The visual record of The Tokyo Riot Graphic not only confirms what we learn from other sources. In two important ways relating to class and to gender, it extends our understanding. Arrest and trial records show the participants, or at least those targeted by the police and the prosecutor, to be quite diverse in occupation and social class.

|

|

Incidents, |

Incidents, |

Incidents, |

In 1908 occupational census: |

|

Merchant/tradesman |

91 (28%) |

64 (30%) |

60 (24%) |

(41%) |

|

Artisan |

82 (25%) |

27 (13%) |

22 (9%) |

(7%) |

|

Outdoor labor/ |

28 (9%) |

13 (6%) |

47 (19%) |

(6%) |

|

Transport/rickshaw |

29 (9%) |

10 (5%) |

7 (3%) |

(11%) |

|

Factory labor |

44 (14%) |

16 (8%) |

53 (21%) |

(14%) |

|

Student |

10 (3%) |

41 (19%) |

10 (4%) |

|

|

Professional/white collar |

13 (4%) |

8 (4%) |

28 (11%) |

(12%) |

|

Unemployed |

20 (6%) |

7 (3%) |

13 (5%) |

(1%) |

|

Other |

10 (3%) |

7 (3%) |

13 (5%) |

(10%) |

|

Totals: |

327 |

214 |

249 |

712,215 |

| Source: Andrew Gordon, Labor and Imperial Democracy in Prewar Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991) | ||||

The only social group significantly under-represented relative to the city’s population among those arrested was the professional class of bureaucrats, doctors, lawyers, journalists, and managers, a category which encompasses the very people who organized the gatherings that ended in riot. Wage labor, broadly defined, was a major element in the crowd, with artisans a leading component in the 1905 (and again in 1906) riots, and factory labor more prominent by 1918. All told, the class composition of the crowd—at least of those arrested—was heterogeneous. Participants came from a broad range of lower- and some middle-class urbanites: masters, artisans, and apprentices, shopkeepers and their employees, factory workers, outdoor laborers, transport workers, and students.

We see this variety confirmed in photos and illustrations from The Tokyo Riot Graphic. In the vicinity of the park on the day of the rally, the camera captured people ranging from gentlemen in relatively formal Japanese dress, a few in Western dress, and working class men in the traditional happi coat. These jackets were decorated with characters indicating an employer or sponsor and worn by rickshaw pullers and day laborers among others.

The arrest records for the 1905 riot included only a few men identified as “office worker” (10 of 273, about four percent). This suggests that men of substance and status, although they led the organizations which called for rallies and spoke at those rallies, did not take major part in the violence which followed. The visual record suggests this was not necessarily the case. It gives relative prominence to men of professional, Westernized appearance. An illustration showing a crowd attacking the offices of the Tokyo Street Railway Company, for example, depicts men in Western dress, including a man in a jacket and necktie in the middle ground who appears to be urging on the crowd.

Another illustration, showing crowds leaping from a stone wall to escape the police, likewise includes a finely dressed gentleman fleeing as fast as he can.

A young woman joins male streetcar passengers reading a September 4 leaflet announcing “a people’s rally.” |

The pages of The Tokyo Riot Graphic also suggest that one group—the women of the capital—although completely absent from the documentary trail of police and trial proceedings was nonetheless engaged with the issues of the day and present at rallies and even among the nighttime crowds watching the riotous action. It is important to note that taking part in these events was illegal for women even if they simply stood and watched. The 1889 “Law on Assembly and Political Societies” and the 1900 “Public Order Police Law” barred women from all forms of political life—not only voting, but joining political organizations, speaking at political meetings, and even attending such meetings.

Once in a while, it seems, they violated these laws and got away with it. A rare example was recorded by the Asahi on September 8, 1913, describing the rallies and the anti-government riot of the previous day sparked by a perceived weak response to the murder of a Japanese man in Nanjing. The formally scheduled rally took place in the center of Hibiya Park, but part of the overflow crowd converged on the bandstand at the park’s edge, creating an impromptu second site for speeches. Suddenly, “Ōno Umeyo, a believer in the Tenri religion and the 19-year-old eldest daughter of Ōno Shūsuke of the village of Tsukitate, Kurihara County, Miyagi Prefecture, ascended the bandstand. She wore a tight-sleeved summer kimono with a purple-blue skirt and had a hisashigami hair style. The crowd cheered and hooted: ‘Fantastic! Hurrah! A new woman!’ and so forth. She raised her voice: ‘Truly it is the duty of the Taishō woman to save our comrades in China.’ With her eloquent words she cut a brilliant figure.” 7

The documentary record of the 1905 riot offers no written reference to any such female participation, but The Tokyo Riot Graphic’s illustrations indicate that women were informed and involved. Illustrating Yano’s account of the buildup to the rally is a woodcut of a vignette inside a streetcar. The fare collector is passing a row of riders. The caption reads “Distribution of Tens of Thousands of Leaflets Calling for a People’s Rally. Sept. 4.” Front and center among a representative cross section of Tokyoites in age, dress, and social type is a young woman closely reading the leaflet.

Similarly, the banner across the cover of this special issue includes a young woman among the six people marching at an angle suggesting determination and perhaps haste. With Japanese flags in hand, these folks may be marching toward a rally site, or marching in one of the earlier wartime victory celebrations. The woman is dressed in the hakama skirt popular among the young women fortunate to attend one of Japan’s relatively few Girls Higher Schools at the time. Educated women in this artist’s conception were one element of the public engaged in the momentous events of the day.

More subtly, some of the artistic illustrations in The Tokyo Riot Graphic also include women in the animated crowd scenes, where it requires careful scrutiny to single them out.

|

|

| A woman in the panic-stricken crowd flees from police brandishing swords on September 6. | |

How reliable are these illustrations as a record of the day’s events? In contrast to the purported battlefield drawings and woodblock prints of both the Sino- and Russo-Japanese Wars, usually rendered from imagination at some distance from the battle front even when the artists were traveling with the troops, the illustrators of The Tokyo Riot Graphic observed the action first hand at close quarters. The offices of the Kinji Gahō were located in the center of Tokyo. Simply standing on the second floor balcony, it was possible for Kunikida and his colleagues, as they recalled, to “see fires here and there, flames rising from 15 or 16 different spots.” 8 (This is captured in the subtle color cover of the special issue.)

Even so, it is course the case that both photographs and drawings reflect choices of photographers and artists. The camera can mislead by omission. A photo editor can do so by cropping. Photographers can ask people to pose or to stage events. But a riot is not a time to easily stage pictures. Although we can never know whose picture was not taken or who was cropped out, we can be reasonably sure those who were captured in the photographer’s lens were present much as we see them.

In the case of hand-drawn illustrations, surely there was some exaggeration for dramatic effect in the depictions of crowds attacking buildings or fleeing the police. But we know from their own accounts that the Fudōsha artists were taught to value careful observation and accurate rendition. In the recollection of one student, the school’s founder, Koyama Shōtarō, enjoined him to “strive to render objects without an iota of difference, as if you had become a camera.” 9

Another student recalls “exhaustive” practice of pencil sketching, with a slightly different emphasis. Koyama told him to “look closely at nature, and draw more carefully, striving not so much for the minute detail of a photograph but for the simplicity that distills the essence of a scene based on careful observation and accurate rendition.” 10 Koyama perhaps tailored his emphasis to the particular needs of each student, but if the Tokyo Riot Graphic artists followed either version of his advice, they are hardly likely to have inserted figures of pure imagination into the scenes of riot as they pursued photographic accuracy or distilled the mood and rendered the essence of these events.

DEMOCRACY & THE CROWD

It is the wide range of loosely connected issues and targets going well beyond simple nationalism and support of empire which justifies seeing in the Hibiya Riots the germination of a drive to realize democracy as well as empire. The illustrations help us see this. Given that the peace treaty was negotiated on the Japanese side in Portsmouth by the foreign minister, Komura Jutarō, the government naturally feared attacks on the foreign ministry. After martial law was declared on September 6, army troops were stationed to guard possible targets, including Foreign Minister Komura’s official residence.

Yet neither the ministry itself, nor the minister’s residence, was subject to a major attack. Rather, and at first glance quite illogically, it was the official residence of the minister of home affairs which became the most important government office to be stormed by a massive angry crowd during the riot.

Located literally across the street from Hibiya Park, the home minister’s residence was certainly a convenient target. But the foreign ministry itself was only one block more distant. A crowd said to number “tens of thousands” made the home minister’s official residence an object of particular fury not simply for its proximity, but rather because this minister stood at the apex of the state agency most responsible for restricting the activities of the people. These restrictions were manifest in the formally political senses of suppressing freedom of assembly and freedom of expression. The nation’s police, including those in Tokyo who had banned the rally, were an arm of the home ministry, and the ministry oversaw censorship of the press. The ministry’s presence, and that of its police force, was also felt in a more general intrusion into people’s daily lives. Yoshikawa Morikuni, one of Japan’s first generation of socialists active in the early-20th century, witnessed what he described as an aged “rickshaw-puller type” ask one of the rioters to “by all means burn the Ochanomizu police box for me, because it is giving me trouble all the time about my household register.” 11

As an agency within the home ministry, the police were thus logical targets of the crowd whether for their role in banning assemblies or for bothering people about their more ordinary obligations to the state. They were also easy targets. Modeled on the Paris police of the late-19th century, Tokyo’s police (and the police around the country as well) were dispersed throughout the city in so-called “police boxes” (kōban), small stations typically manned by two officers, with a desk in a front room open to the street for easy observation and communication with residents, and a back room for sleeping. When officers cultivated trust with the neighborhood, the system of ubiquitous boxes provided effective community policing. But when trust broke down, the scattered police boxes were defenseless in the face of attacks by large crowds.

The rioters destroyed nearly three quarters of all the boxes in the city. The Tokyo Riot Graphic prominently placed a dramatic illustration of one such attack on its inside cover page, along with photographs of two demolished boxes.

With others, editor Kunikida saw this destruction as portentous. As he gazed at fires burning around the city center from the roof of the building that housed the editorial offices, he is reported to have mused to a colleague that “I wonder if a revolution has actually started?” 12 Kunikida selected illustrations to convey this volatile and violent situation to readers which figuratively brought the war back home; their composition and feel drew on artistic tropes already developed in illustrations sent back from the war zone by the Graphic’s artists over the previous 18 months.

Other targets during this and the later riots provoked enmity for their role in support of the bureaucratic state and its allies in the political parties. These included pro-government newspapers as well as politicians and their parties. The politician targeted most often was Hara Takashi, the home minister at the time of the Hibiya Riot, and his Seiyūkai Party was a repeated target of popular fury as well.

One further target was the city’s streetcars and the company that ran them, attacked in the 1905 riot and two smaller incidents the following year (one on the anniversary of the Hibiya Riot) for both economic and political reasons. The streetcars were relatively new, having begun service in 1903, the same year that Hibiya Park opened. They were expensive for ordinary Tokyoites. They threatened the livelihood of the city’s many thousands of rickshaw pullers, who were numerous among the rioters and those arrested. Streetcar passengers had been subject to the transport tax to finance the war, at the rate of one sen per ride added to the base fare of three sen. And rumors abounded that the service was initiated thanks to a sweet deal struck among Home Minister Hara, members of his party in the Tokyo city council, and the streetcar company itself. All three parties were criticized for having profited at the expense of ordinary people.

In sum, these ferocious and lavishly illustrated attacks were not random. Nor were their targets directly connected to the issue of empire at the political forefront of the day. The crowd targeted those seen to suppress people’s freedom of assembly and expression, as well as those seen to impose economic hardship and be shadily connected to the home ministry and the political allies of its leader. Attacks on the home minister, his police, and the streetcars evinced a populist and democratic, if also a violent, spirit.

This article is also available in another formatting at the Visualizing Cultures website.

Andrew Gordon teaches modern Japanese history at Harvard University with a primary research interest in labor, class and the social and political history of modern Japan. He is the author of A Modern History of Japan and the editor of Postwar Japan as History. His most recent book is Fabricating Consumers: The Sewing Machine in Modern Japan. He is an Asia-Pacific Journal associate.

The Visualizing Cultures website includes the complete image gallery from a special edition of The Tokyo Riot Graphic, No. 66, Sept. 18, 1905, by Andrew Gordon.

Recommended Citation: “Andrew Gordon, Social Protest in Imperial Japan: The Hibiya Riot of 1905,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 29, No. 3, July 21, 2014.

NOTES

1 On Yano’s encounter with the British illustrated publications, Yamada Naoko, “Jūgun shita gakka tachi: ‘Senji gahō’ ni okeru fudōsha monjin no katsudō” Joshi bijutsu daigaku kenkyū kiyō No. 33 (2004), p. 165 and Kuroiwa Hisako, Kunikida Doppo no jidai(Tokyo: Kadokawa shoten, 2007), p. 61.

2 The Western woodcut engravings were literally done against the grain of the block of wood, in contrast to Japanese wood block engravings which ran with the grain. This accounts for difference in the appearance of the two sorts of woodblocks. The Japanese illustrated publications of this era generally followed the Western practice rather than the traditional Japanese one.

3 Hiratsuka Atsushi, “Kinji gahōsha jidai no Doppo-shi,” Shinchō (7/15/1908), p. 128.

4 For a slightly more detailed narrative of the riot: Okamoto Shumpei, “The Hibiya Riot,” in Tetsuo Najita and J. Victor Koschmann eds., Conflict in Modern Japanese History:The Neglected Tradition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), pp. 258-262.

5 Tokyo Asahi Shinbun, September 8, 1913, p. 5

6 Andrew Gordon, Labor and Imperial Democracy in Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), p. 54.

7 Tokyo Asahi Shinbun, September 8, 1913, p. 5

8 Kuroiwa, Kunikida Doppo no jidai, p. 131.

9 Kuroiwa, Kunikida Doppo no jidai, p.72.

10 Yamada, “Jūgun shita gakka tachi,” p. 174.

11 Takahashi Yūsai, Meiji keisatsu shi kenkyū (Tokyo: Reibunsha, 1961), Vol. 2, p.103.

12 Kuroiwa, Kunikida Doppo no jidai, p. 131. His phrasing was “iyoiyo kakumei ga hajimatta ka naa?”

13 On Okoi’s role in the riot and its aftermath, see Kuroiwa Hisako, Nichiro sensō: shōri no ato no gosan (Bungei shunju, 2005), pp. 46-52, 95-100, 182-192.

14 Kuroiwa, Kunikida Doppo no jidai, p. 131.