Generals preparing to go to war are, we are often told, fond of reading military classics on the Art of War. Some of the stories may be apocryphal – did Norman Schwarzkopf really have a copy of the ancient Chinese strategist Sunzi on the subject in his back pocket when he launched the Gulf War, or did Napoleon have it at his bedside? – but it is certainly studied widely, along with Machiavelli’s essay of the same title, and Clausewitz’s On War, at West Point, Sandhurst and Saint Cyr. So are the strategies and manoeuvres of classical military engagements from the Greco-Persian Wars of the 5th century BC through to the Crimean and Franco-Prussian Wars of the 19th century and on into the world conflicts of the 20th century. The curriculum of the PLA National Defence Academy in Beijing, which claims to be China’s equivalent of West Point, no doubt has a similar historical and geographical breadth. The academic study of war, while recognising the shift to what is generally called ‘modern warfare’ brought about by the Napoleonic wars (or, in some views, rather earlier) also takes a longer and wider view of the subject. As the British war studies professor Lawrence Freedman has observed, ‘The [strategic] debates of today can be traced back to those of classical times, so that Thucydides’ account of the Peloponnesian wars from 400 BC can still serve as a starting point for analyses of the causes of war while Machiavelli can still be read with profit by aspiring strategists.’1 The form of war, it is acknowledged, may change significantly, and new terms need to be coined – such as the concept of asymmetrical warfare – to keep pace with such change, yet war as a human activity is seen to possess a timeless quality which should continue to merit our attention and study. For ‘war antedates the state, diplomacy and strategy by many millennia’, wrote the military historian John Keegan. ‘Warfare is almost as old as man himself, and reaches into the most secret places of the human heart…’2 War is thus regarded as a seamless historical phenomenon: third-year students of War Studies at Kings College, London, may choose from a list of options ranging from Warfare in the ancient world’ to Insurgency and counter-insurgency in the modern world. This is not contradicted by the growing interest in what is referred to as the changing character of war (currently the subject of a major project at Oxford University). War is seen as both constant and changing: as a recent study argues, one of the key challenges that strategists face is ‘balancing the tension between the constantly changing character of war and its underlying, unchanging nature’.3

The same argument can reasonably be made of peace – often referred to as the ‘opposite of war’ (though it is much more than that). Our understanding and definition of peace in the modern context is broader and more complex than in the past, recognising that in a globalised world peace also requires a global dimension, and must encompass issues of economic and social justice and equality which go far beyond the mere ‘absence of war’. Yet peace is also a universal phenomenon with a long history, and the human desire for a peaceful environment in which society can flourish is as deep-seated as the human impulses which lead to destructive war. Peace, as even Thucydides (who in his History was much more interested in war) acknowledges, ‘brings its own honours and splendours and countless other advantages, which are free from danger and would take as many words to enumerate as when we describe the evils of war’.4 The blessings of peace and the case against war are a constant theme in human discourse from ancient times to today. As I have sought to show in my book on The Glorious Art of Peace5 powerful arguments against war were made by classical Chinese and Greek thinkers, by the early Christian fathers and even during the Crusades. A continuous narrative of peace can then be traced from the time of Desiderius Erasmus and fellow-humanists of the Renaissance, through Kant and other philosophers of the Enlightenment, to the peace societies and conferences of the 19th century whose efforts to find international mechanisms for preventing war and negotiating differences between states paved the way ahead to the League of Nations, and ultimately to the United Nations. Nor is the subject confined to argument and theory. Peace in action – the attempts by individuals, groups and whole societies, to resist violence and protest peacefully – is by no means a modern phenomenon as sometimes suggested with the notion that ‘non-violence began with Gandhi’. While historians have paid less attention to it, we can still find evidence of popular opposition to war and the demand for peace (though often in chronicles which were unsympathetic to the aspiration).

However, peace has very obviously a much lower visibility than war, and many people are unaware that there is a science of peace which is every bit as complex and rich as the science of war. A survey of the shelves of any large bookshop or library will illustrate the point: It is much easier to find Sunzi on the Art of War than the thoughts on peace of his Chinese contemporary Mengzi, Machiavelli’s militaristic counsel to The Prince is much more accessible than the pacific advice to another Prince of his Renaissance contemporary Erasmus, Clausewitz’s thoughts On War are more likely to be on the shelves than the reflections On Perpetual Peace by his fellow thinker of the Enlightenment Immanuel Kant. And for a round-up of thinking on peace and war, while Professor Freedman’s Oxford reader On War is generally available, the Oxford reader on Approaches to Peace6, is much less so. The record of a century of peace advocacy from the mid-19th century onwards is also little discussed outside specialist studies with a few notable exceptions such as Barbara Tuchman’s extended treatment of the two Hague Peace Conferences (1899 and 1907) in her portrait of ‘the world before the [first world] war’.7 (By contrast, the Hague conferences were not mentioned at all by the renowned British historian A J P Taylor in his classic work on European diplomacy leading up to the war. (The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918 1848-1918).

While the history of war is seen to be relevant to the study of international relations, the history of peace is much less central – outside the field of peace studies which, in spite of its impressive growth of the last three or four decades, still struggles to be inserted into the mainstream of academic discourse. We may also note the relative lack of attention paid by mainstream media: war historians are far more likely to be asked to voice their opinion on current issues of war and peace than are peace historians. And while the lessons of past wars and the teaching of classical war thinkers are regarded as relevant by those engaged in the practice of war, diplomats engaged in peace negotiations are much less likely to keep in mind the lessons of past eras of peace – and far less likely to have a copy of Erasmus in their back pocket. This is not to devalue the very considerable input in recent years from peace study institutions and scholar-activists in attempting to mediate and promote peace and justice in countries or regions emerging from war. The pioneer British Quaker Adam Curle (1916-2006), for example, worked, as his obituary noted, ‘to bring people together in conflict-torn areas, including India, Pakistan, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka and the Balkans’.8 Since the escalation of intra-state conflict following the end of the Gulf war, there has been a huge increase in the demand for help in peace-building, both in terms of theory and practice, from peace institutions working through NGOs and government.9 The work of peace researchers, especially on promoting the conditions for peaceful economic and social develoment, is drawn on extensively by the specialised agencies of the UN and by governmental foreign aid agencies.10 There has been a significant effort in a number of countries to promote education in schools about problems of violence and strategies for peace.11 Graduates in peace studies work in both governmental and non-governmental institutions to promote peaceful change.12 Yet we should note that while the peace studies community has made and continues to make a significant contribution to a range of conflict-related issues, its assistance is more likely to be called upon (a) after the event and (b) in situations of intra-state conflict, while neither current peace ideas nor the rich history of peace thought are generally admitted into public debate in cases of major conflict between states – precisely those cases which pose the greatest threat to world peace. It is no wonder that for peace historians it is still an open question as to how much influence peace history has had on foreign policy and attitudes toward international relations.13

There may also be a cultural dimension in the comparative neglect of the history of peace thought and action. Self-consciously modern in outlook, many societies tend to trace their political culture a relatively short distance back over time, and to regard the moral and social postures of earlier times as old history’ in both senses of the phrase. More recent history also casts a shadow. To call for peace’ is to risk confusion with ‘the appeasement’ of the 1930s, or with the ‘peace campaigns’ of the cold war period. For peace advocates, it may even seem more prudent to describe oneself as opposed to war rather than in favour of peace. There is an interesting contrast here with the approach of the Chinese government whose representatives now explicitly invoke the thought of ancient philosophers, including Kongzi (Confucius) and Mozi, in order to give weight to the claim that China pursues a foreign policy based upon harmony and peace, and that China has no ambitions for expansion abroad. The official Chinese news agency from time to time publishes authoritative commentaries along these lines that are disseminated by Beijing’s embassies around the world. One such example, distributed on Chinese National Day 2007, was titled ‘Harmonious World: China’s Ancient Philosophy’.14 (Needless to say, such an approach would not have been adopted during the era of Mao Zedong when ancient philosophy except for the Legalist school was rejected as part of the feudalist past). To what extent this cultural attachment to the past has operational significance is a matter for debate, but it does appear to reflect a sense of continuity with the past, something which is lacking in many Western societies.

Yet we need to be more aware that over the last two millennia there has been a powerful and multi-stranded narrative of peace, expressed in different forms and in different environments, challenging the more familiar dialogue of war. This trajectory of pacific thought is not just of scholarly interest but can still enrich our contemporary debate on how to fashion a more peaceful world. Here I shall trace it (briefly and selectively) from ancient Greece and China, through early Christian thought to the humanist thinkers of the Renaissance, onwards in an increasingly rich dialogue through the Enlightenment into the 19th century when peace became a campaigning issue and the modern peace movement can be said to have emerged. I shall then consider what lessons we can draw from this still under-explored wealth of peace thinking which may continue to be relevant today.

A. The history of peace thought

The ancient world:

The early history of the two oldest world civilizations still extant today, those of the Greek and the Chinese peoples, appears dominated by warfare and martial values, stretching over the first millennium BC — from Mycenaean Greece and the Shang dynasty of China to Greek city-states and the Chinese Warring States period. We might suppose that there is very little to learn about peace rather than war from such an epoch, yet if we look carefully the surviving works of Greek and Chinese history and literature reveal a rather more complex narrative.

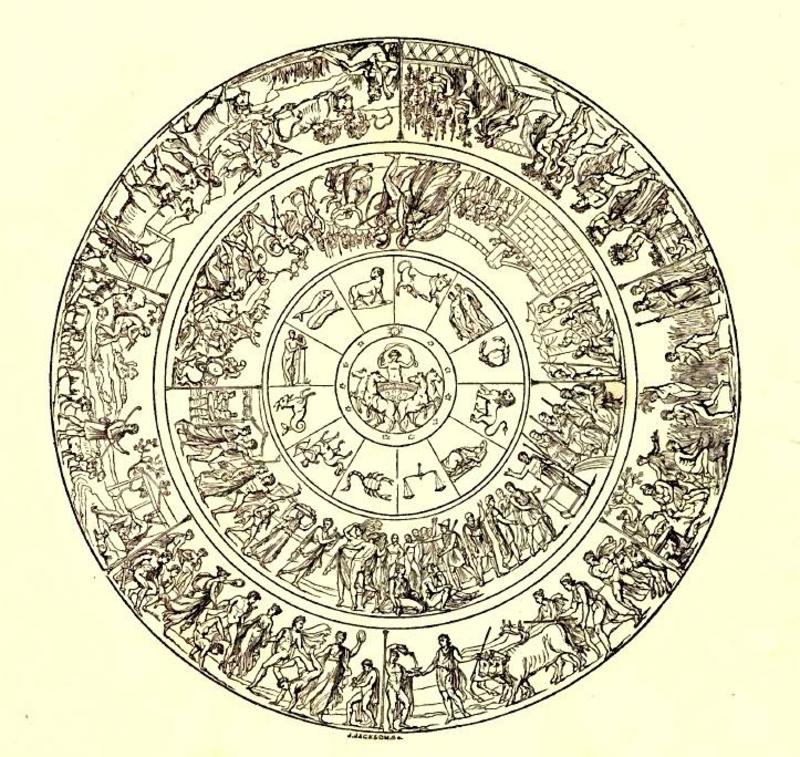

Homer’s Iliad may seem unpromising material for an enquiry into attitudes towards peace in ancient society. Yet as the Iliad‘s translator E V Rieu observed, ‘the Iliad was written not to glorify war (though it admits its fascination) but to emphasize its tragic futility’.15 Homer has woven into his narrative of the war which was fought a counter-narrative of peace which it denied. This is evident particularly in his depiction of the Shield of Achilles. Where one would have expected this to bear fierce images to terrify the enemy, the Shield, as described by Homer, is covered mainly by images of peace, plenty, and normal life, including festivals and dancing, ploughing and harvesting, the gathering of grapes and the herding of cattle. Homer here is depicting in detail the life which should be desired yet which is rendered impossible by conflict.16

|

An imaginative reconstruction of The Shield of Achilles as described by Homer, published in The Art-Union Scrap Book (London: H G Bohn, 1843) |

Our perception of classical Greece in the city-state era (5th to 4th centuries BC) is also dominated by war, although there were constant efforts, sometimes resulting in success, to maintain peace through treaties and diplomacy. The history of this period has been biased by the war-oriented approach of Thucydides who presents at length the arguments of the war party in the Athenian Assembly, but barely mentions those who urged peace. Thus the speech by Pericles advocating war with Sparta (432 BC) is given in full, while the argument of those urging compromise is summarised in half a sentence. Later, in describing the peace concluded in 422 BC by the Athenian leader Nicias, Thucydides barely mentions war weariness as a factor. We must rely on Plutarch’s much later life of Nicias for a rare glimpse (in a passage based on a source no longer available to us), of the strong desire for peace among the Athenians and the wish to ‘become friends’ with the Spartans.17

The surviving Greek plays from this period also suggest that pro-peace arguments could be more easily argued on the stage where playwrights were allowed dramatic license to put the case against war. This is true not only of the comedies of Aristophanes whose anti-war satire in Peace, the Lysistrata and The Archanians is well known but in the works of the great tragedians. In Seven Against Thebes, Aeschylus depicts a fratricidal conflict in which the two brothers die at each others’ hands, while a chorus of women laments the loss of life among their followers. Two remarkable plays, Sophocles’ Ajax and Euripedes’ Herakles, describe the descent into madness of the two war heroes concerned in terms which seem to evoke what we would now call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.18 War and its effects is the underlying theme in most of the surviving 17 works of Euripides.

Early Chinese texts also reveal more concern with issues of peace than might be supposed. We may note the laments of the peasant soldiers and their families, vividly expressed in many of the lyrics in the Asia-Pacific Journal. The record of war and intrigue in the Chronicle of Zuo (Zuo zhuan), on close enquiry, also reveals a wide range of thought and argument in which rulers and their advisers considered seriously questions of both morality and expediency in the exercise of power, weighing up the benefits of peace against the advantages of war. We may also discern, during the period of the Warring States which led to the first unification of China (221BC), a vigorous debate between scholar-advisers of the different schools of thought — the so-called Hundred Schools — on the merits of peace and war. As well as the more familiar positions of Sunzi, and of the pro-war Legalists, powerful arguments in favour of peace were made at the court by Confucian and Mohist scholars in terms with which we may still identify (I have discussed these arguments at length in a recent article published in The Asia-Pacific Journal).19

Early Christianity and peace: The early Christian fathers thought deeply about peace, raising questions—still relevant today—about the real meaning of the injunctions of Jesus Christ, and the balance to be struck between temporal and spiritual obligations. Christians in the imperial service of Rome faced a hard choice between unquestioning obedience and conscientious objection. The message of the early fathers, such as Origen and Tertullian, was that Christianity (in the phrase of Justin Martyr)’ had changed the instruments of war, ‘the swords into ploughs and the spears into farming implements’. This record of early Christian pacifism has been played down and sometimes ignored altogether in some standard histories of the origins of Christianity. One of the most striking stories from this period is that of Martin (b. AD 316), the young Roman soldier who told his emperor that he would henceforth refuse to fight and become a solder of Christ instead. Even after the historic compromise between the church and the Emperor, this story shows, there were Christians who continued to believe that military service was incompatible with their faith. The tale of Martin could be described as one of the first recorded cases of conscientious objection. All the more amazing therefore, that in an ironic reversal of roles, St Martin of Tours has become in the Catholic faith the patron saint of soldiers!

|

Simone Martini, St Martin Renounces his Weapons’ c. 1320, Basilica di San Francesco, Assisi |

The role of St Augustine (AD 354-430) has been subjected to similar distortion: in many accounts, his greatest contribution was to resolve the dilemma faced by early Christians between their temporal and spiritual obligations by formulating the doctrine of the Just War, of which he is said to be the ‘father’. Yet nowhere in Augustine’s abundant writings is this doctrine spelt out clearly and he would not approve of the use which has been made of his words to justify numerous wars. In his great work The City of God, Augustine was far more eloquent on the subject of peace. ‘In the city of man as well as in Heaven,’ he wrote, ‘there is a desire for peace which may be achieved on earth to some degree. Even the warrior who had to take up arms,’ said Augustine, should regard ‘the prevention of shedding blood as his real mission’. Man’s nature moves him powerfully ‘to maintain peace with all other men as far as he is able’, and anyone who can contemplate warfare without heartfelt grief has ‘lost all human feeling’.

The Crusades is another episode in history where the voices of the warriors and those who support them sound loud and clear down the ages, while the voices of those opposed to such adventures are heard dimly if at all. Opposition within sections of the Church and nobility, and in the emerging urban societies, can usually only be discerned through the counter-arguments deployed by advocates of the Crusades. The clearest evidence for opposition in the late thirteenth century comes in the memorandum of Humbert of Romans, the senior Dominican who sought to demolish the arguments of the critics. Humbert cited in detail eight hindrances’ to the crusade, and seven types of men who objected to it: foremost were those who believed that the Crusades were not compatible with Christianity.

Peace thought in the Renaissance: The modern debate on peace and war may be said to have begun in the renaissance, with the arguments of two great scholars in the humanist tradition, Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) and Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536), occupying opposite poles. The contrast may be illustrated by these two pieces of advice, both taken from essays intended to instruct a prince on how to conduct himself as a ruler.

Erasmus: The first and most important objective is the instruction of The Prince in the matter of ruling wisely during times of peace, in which he should strive his utmost to preclude any future need for the science of war. (Education of a Christian Prince, 1516)

Machiavelli: A Prince ought to have no other aim or thought, nor select anything else for his study, than war and its rules and discipline; for this is the sole art that belongs to him who rules. (The Prince, 1513)

Though the two scholars were contemporaneous there is no record that they actually met. However they were both in Florence at the same time and witnessed a significant military event in neighbouring Bologna from which they drew opposite conclusions — the siege of the city in 1506 by the army of the warlike Pope Julius II (known as Julius the Terrible). For Erasmus this demonstrated the negation of everything that kings and popes should stand for: Was Pope Julius the successor of Jesus Christ, he asked, or of Julius Caesar? Later he would write a satirical dialogue in which the Pope, drunk and boasting of his military victories, is denied entry to Heaven by St Peter! Machiavelli on the other hand admired the Pope’s firmness of purpose in pursuing his campaign and his refusal to be bound by peace treaties which had been made between previous Popes and the city of Bologna. Later Machiavelli would praise qualities of this ruthless kind in The Prince.

Erasmus was the most eloquent as well as the most prolific of a group of Renaissance humanists who, in the early sixteenth century, sought to convince the rulers of the emerging European nation-state system that the interests of potentate and populace alike were best served by peace, not war, and who for a short while believed that their arguments might prevail. Erasmus was in his time much better known than Machiavelli, and his books circulated widely (Henry VIII possessed his own copy of the Education of a Christian Prince). His writings on the subject of peace would if collected together occupy some 400 pages of a modern book. Yet we will search today to find these works. Usually the only available title is his In Praise of Folly (1510), a jeu d’esprit written for the amusement of fellow-humanist Sir Thomas More — the only work by Erasmus to have been published in the Penguin Classics series. This may be contrasted with the ready availability of many of Machiavelli’s works. The catalogue of the well-stocked Oxfordshire library service lists 16 editions of works by Machiavelli, and only two by Erasmus.20

Peace thought in the Enlightenment: Free-minded thinkers in the age of Enlightenment identified clearly the threat posed by shifting alliances of nations led by wilful rulers who resorted to war without regard for the suffering it caused. Their thinking was linked by a loose but coherent thread, referring to advocacy from Erasmus (whose works enjoyed a revival) onwards. Among their forerunners the French monk Émeric Crucé (1590-1648) stands out: in the Nouveau Cynée he proposed a permanent Council of Ambassadors to resolve disputes between states, to be located in Venice. The Quaker scholar and founder of Pennsylvania William Penn (1644-1718), in his Essay Towards the Present and Future Peace of Europe (1693), set out a more detailed structure for a pan-European council. The French rationalist and early Enlightenment thinker the Abbé de Saint-Pierre (1658-1743) drew on earlier works for his own Project for Perpetual Peace (1712). Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-78) would edit Saint-Pierre’s Project, adding a ‘judgement’ or commentary of his own. This discourse of peace in the Enlightenment reaches its peak with Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), whose essay On Perpetual Peace has received more attention than its predecessors. Kant’s plan for a League of Nations (he was the first to use the term), although conceived in a restricted sense, would have a practical influence on the Versailles negotiations a century later.

Kant argued against secret treaties and against the use of mercenaries and for the abolition of standing armies and a republican form of government. Kant’s overall vision of perpetual peace is at points difficult to interpret, but he clearly perceived that the maintenance of world peace has to be a joint endeavour, and he identified the lack of what we would now call enforcement’ as a major problem. Kant has been unfairly accused of advocating an unrealizable utopia: he believed that peace is achievable but not inevitable, concluding that it depended in the end on human efforts:

In this manner nature guarantees perpetual peace by the mechanism of human passions. Certainly she does not do so with sufficient certainty for us to predict the future in any theoretical sense, but adequately from a practical point of view, making it our duty to work toward this end, which is not just a chimerical one.

Peace thought and action in the 19th Century: The peace societies which began to emerge after the Napoleonic Wars, drawing on a wider social and geographical basis, and driven by the horrors of modern conflict, made it possible for the first time for the voices of tens of thousands rather than of a handful of scholars to be heard on the subject of peace. Although they suffered drastic reversals and were easily silenced by the shrill sound of patriotism whenever a new war broke out, they quickly came back to life when the costs of such a war were reckoned up. By the end of the century they could even lay claim to the support—however equivocal—of a Russian tsar and a multitude of European government ministers. It is easy to dismiss the nineteenth century peace movement for placing too much faith in the power of persuasion and for underestimating the strength of militarism. Yet the First Hague Peace Conference of 1899 did achieve practical results in the fields of arbitration and the regulation of rules of war, while peace and disarmament were placed on the international agenda, where they have remained ever since. The human cost of war, dramatised by a series of senseless conflicts including the Crimean War (1853-6), the Franco-Austrian War (1859) and the Franco-Prussian War (1870- 1), also led to first steps towards an international humanitarian law, notably the establishment of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

The movement brought together Christian evangelists, Quakers with a previous history of peace commitment, and secular humanitarians in seeking a more peaceful world. They were driven not only by considerations of morality and compassion, but increasingly by rational arguments as to the harmful socio-economic effects of war and military preparation. By the end of the century there had emerged a shared vision of liberal internationalism which saw the need for global organisations which could provide international security without resort to violence. Advocates of peace in the period leading up to World War 1 include Noah Worcester, Elihu Burritt, Richard Cobden, Victor Hugo, Henry Richard, Bertha von Suttner, Jean de Bloch, Jacques Novikow, John Ruskin, William James, Norman Angell and H G Wells. Today their arguments are mostly either neglected or dismissed as unrealistic, while the peace-directed thoughts and words of the great writers are glibly dismissed as unrelated to the real genius of their work. Yet the evolution of Tolstoy’s thoughts can be traced from his powerful reporting of the Crimean War (which was subjected to Russian censorship),21 through War and Peace when he was still trying to reconcile the apparent inevitability of war with its essential immorality, to the complete rejection of violence and adoption of total pacifism in his later years. Similarly in the case of Hugo, we can trace a consistent development of his thinking on peace from his address to the first great Peace Conference of 1849 – when he made a prescient appeal for European unity which would make war obsolete – to the impassioned denunciation of war in his speech on the centenary of Voltaire’s death (1878) in which he drew a powerful connection between the peace thought of the Enlightenment and the peace campaigns of his own time.

Let us give the word to those great voices [of the Enlightenment]. Let us stop the shedding of human blood. Enough, enough, you despots! If barbarism persists then philosophy must protest. If the sword is relentless, then civilisation must denounce it. Let the 18th century come to the aid of the 19th century! The philosophers who came before us are the apostles of truth, let us invoke the illustrious shadows of those who, faced by monarchs who dreamt of war, proclaimed the human right to life, the right of conscience and freedom, the supremacy of reason, the sanctity of work, and the blessings of peace. And, since the thrones of our monarchs cast us into darkness, let the tombs of these great thinkers restore us to the light!

|

Victor Hugo addresses the Paris Peace Conference, Illustrated London News, 1 September 1849 |

B. The Lessons of Peace History

The above account of peace thinking from ancient times to the end of the 19th century is necessarily selective. It does not cover the history of heterodox pacifist thought which has been brilliantly rescued from obscurity by the peace historian Peter Brock).22 Nor have I attempted to consider how peace has been regarded in the religious traditions of Islam and Buddhism — both areas on which much research remains to be done. Yet this survey should be sufficient to dispel two common myths: either that concern for peace is a relatively modern conception, or that opposition to the war in the past was based on utopian or idealistic arguments of little relevance today. A further criticism also needs to be dealt with; that even if peace advocates in historical times did address practical issues, the character of war has changed to such an extent that what they had to say is still of little relevance today. To this I would reply that while the character – or at least the form – of war has changed in some (though not all) respects, the thinking which leads governments to opt for a military solution while rejecting or downgrading peaceful alternatives, and therefore to choose war as an instrument of policy, remains substantially unchanged. What Mengzi or Erasmus or Penn or Kant or Hugo or von Suttner had to say about peace is not only of great historical interest, it can also illuminate our own efforts to strive for the same goal. (If they had been listened to, we may suggest, there would have been no Iraq War!). A desire for peace has been woven into the fabric of human consciousness not just in recent times but throughout history, and knowledge of this rich historical record of peace thought and argument should sustain and encourage our own efforts.

The Benefits of Peace: Rejecting the view that war is in some way essential for human development, the peace thinkers of the past concur in their appreciation of the beneficial character of peace – indeed that the condition of peace is indispensable for the growth of civilisation. Peace, as Erasmus put it eloquently, ‘is at once the mother and nurse of all that is good for humanity…. Peace shines on human affairs like the sun in springtime.’ St Augustine also wrote at length on the benefits of peace, linking this to the argument – fundamental to his philosophy – that human beings should live the best, and most peaceful lives possible rather than simply wait for the life hereafter.

[God has] imparted to men some good things adapted to this life, to wit, temporal peace, such as we can enjoy in this life from health and safety and human fellowship, and all things needful for the preservation and recovery of this peace, such as the objects which are accommodated to our outward senses, light, night, the air, and waters suitable for us, and equitable condition, that every man who made a good use of these advantages suited to the peace of this mortal condition, should receive ampler and better blessings, namely, the peace of immortality, accompanied by glory and honour.23

Kant has a more sophisticated view of the role of peace in human development. He is no idealist (contrary to the charge laid against him by some war historians), and even asserts that ‘the natural state of humans living side by side is one of war’. But, he continues, humanity has now reached the level, through a process of repeated wars, at which the danger of continued war and its adverse effect on economic development, will oblige the new nation-states to formulate and abide by international law, and that this should in time lead to global harmony and agreement.

Here we may see that Kant has anticipated Charles Darwin who – again contrary to popular misperception – believed that competition within the human species would, as civilisation evolved and as communities grew larger, give way to the realisation that cooperation could be a more effective driver for progress and development. The following passage from The Descent of Man should, I suggest, be a compulsory element in any discussion of Darwinism.

As man advances in civilisation, and small tribes are united into larger communities, the simplest reason would tell each individual that he ought to extend his social instincts and sympathies to all the members of the same nation, though personally unknown to him. This point being once reached, there is only an artificial barrier to prevent his sympathies extending to the men of all nations and races….

This virtue, one of the noblest with which man is endowed, seems to arise incidentally from our sympathies becoming more tender and more widely diffused, until they are extended to all sentient beings. As soon as this virtue is honoured and practised by some few men, it spreads through instruction and example to the young, and eventually becomes incorporated in public opinion.24

Peace theorists of the late 19th century such as Jacques Novikow and Jean de Bloch25 built upon Darwin’s approach, seeking to show that peaceful economic competition had replaced armed conflict as man’s principal activity, and pointing to the role of science and technology in promoting peaceful development. Here they were combating the arguments of the so-called Social Darwinists who distorted Darwin’s own findings in order to assert the ‘necessity of struggle’, and who argued that war would continue to be the driving force for all human progress,

Education for Peace: Peace thinkers from the earliest time have understood the importance of persuasion: their rulers had to be convinced that the cost of war will almost always be higher than the cost of any compromise necessary to avoid war. As Erasmus put it in The Education of a Christian Prince, the effects of war are so damaging that the wise prince will ‘sometimes prefer to lose a thing [by not fighting] than to gain it [through war]’. And even more bluntly in his The Complaint of Peace, ‘Hardly any peace is so bad that it is not preferable to the most justifiable war’. In modern terms, we might say this is a question of accurate cost-benefit analysis, with the problem that too often the short-term gains of war are not properly measured against the long-term negative consequences.

In seeking to persuade potential war-makers of the dangers of seeking peace through war, one also has to combat the arguments of those with a vested interest in arguing the opposite. The Confucian peace advocates of the Warring States period made no secret of their loathing for the Strategists and Legalists who urged their rulers to make war. ‘The so-called good ministers of today [who advise their prince to go to war] would have been called robbers of the people in olden days’, commented Mengzi. His successor Xunzi, when asked by the ruler of his native state what was the best way for a king to manage his army, replied dismissively that ‘such detailed matters are of minor importance to Your Majesty, and may be left to the generals’. Xunzi shared Mengzi’s insistence that what was of real importance was to rule with humanity and justice, and that unity between the ruler and the people was the best way to resist aggression.’ ‘For a tyrant to try to overthrow a good ruler by force would be like throwing eggs at a rock or stirring boiling water with your finger’.

Peace advocates of the Enlightenment, in the age when armies were becoming professional and the military establishment gained more power in the courts of the nation-states, recognised the growing strength of the vested interests for war, and the difficulty experienced by kings and princes in resisting their pressure. The dilemma was eloquently put by Denis Diderot, author of the great Encyclopédie (c. 1760), in which Peace was given its own entry and definition:

The sovereign has need of unalterable firmness, and an invincible love of order and the public good, to resist the clamour of those warriors who surround him. Their tumultuous voice constantly stifles the cry of the nation whose sole interest lies in tranquillity. The partisans of war have no shortage of pretexts with which to stir up disorder and make their own self-interested wishes known.26

By the mid-19th century, the existence of what we would now describe, following President Eisenhower’s warning, as the military-industrial establishment, was a stock theme in the discourse of the newly emerging peace societies. There is a large portion of the community which does not want peace’, warned the British radical parliamentarian Richard Cobden. ‘War is the profession of some men, and war, therefore, is the only means for their occupation and promotion in their profession’ (speech at Wrexham, November 1850).

Mediation for Peace: The advocates of peace have always recognised that it will not come by itself, that hard work is needed to avert conflict between rival parties, and that this will require a negotiated solution. St Augustine understood this very well, declaring that ‘It is a higher glory still to stay war with a word, than to slay men with a sword, and to procure or maintain peace by peace, not by war’. Erasmus too had a very clear idea about the need for some form of mediation between those about to go to war:b

There are laws, there are scholars, venerable abbots, reverend bishops, by whose prudent counsel the matter can be composed. Why not try these arbiters, who can hardly create more problems and are likely to cause many fewer than if recourse were had to the battlefield?27

As the new world order of nation-states began to take shape, peace advocates began to explore means of establishing more permanent mechanisms through which to mediate conflict and if necessary to enforce a settlement. William Penn’s proposal for a pan-European council amounted to a permanent international tribunal, in which the European countries were represented by delegates in numbers corresponding to their economic power. Penn even anticipated modern conference procedure by setting out rules for the layout of the council chamber: the room should be round and entered by more than one door to prevent any quarrel over precedence. In his Project for Perpetual Peace, the Abbé de Saint Pierre proposed a League of European States with a permanent Congress of Representatives, and a Senate with powers to arbitrate disputes and enforce its decisions if necessary by military sanctions, while all peacetime armies were to be reduced in size to no more than 6,000. Kant also began to explore the relationship between individual states and the community of nations, proposing a ‘federation of states which could in theory lead to perpetual peace’ – although in practice he conceded that this is unlikely to be achieved, and that we must settle for a more limited alliance to prevent specific wars.

The peace societies of the 19th century, while stressing the moral case against war, placed the main emphasis of their argument upon its economic irrationality, and on the possibility of resolving disputes by peaceful means – and in particular through international arbitration. In a modest early success, at the Paris conference which ended the Crimean war, a peace deputation led by Richard Cobden persuaded the delegates of the great powers to include in the treaty a protocol expressing the desire’ for recourse to mediation in future disputes. The campaign to promote international arbitration as the way to settle disputes by peaceful means rather than by war was boosted by a provision in the 1871 Treaty of Washington between Great Britain and the United States in which a contentious issue (the Alabama dispute’) was referred to an arbitration committee in Geneva. In Britain Henry Richard, secretary of the Peace Society and a Liberal MP, scored a notable victory by proposing a parliamentary motion in favour of arbitration, and winning an unexpected majority

While spending so much of time, thought, skill, and money in organizing war, is it not worth while to bestow some forethought and care in trying to organize peace, by making some provision beforehand for solving by peaceable means those difficulties and complications that arise to disturb the relations of States, instead of leaving them to the excited passions and hazardous accidents of the moment? (Hansard, 8 July 1873)

By the end of the 19th century, peace activists could claim a share of credit for dozens of bilateral treaties and agreements between states with provisions for the peaceful arbitration of disputes. Plans for obligatory arbitration on a wider international scale, and for the creation of a real international judiciary, began to be discussed. Though optimism was already fading by the time of the second Hague Peace Conference in 1907, the peace societies had sown the seeds for a society of nations which, after the war, would germinate into the League of Nations (and in turn pave the way for the United Nations). Overall, these were significant gains.

The globalisation of peace: We have become increasingly familiar over the last century with the concept that peace is indivisible and that it is not enough to have the absence of war without freedom from oppression and hunger unless these advantages are shared by one’s neighbours. This approach acquired a global reach in the post-cold war period of the 1990s, with the concept of human security promoted by the UN Development Programme in its Human Development Reports. It has been carried a stage further by this organisation (ORG) in formulating the concept of sustainable security, which addresses both the continuing inequalities of world society, and the new types of security threats of the 21st century.28 It has also been developed in the concept of ‘cosmopolitan peace’, proposed by the international historian Ken Booth, in which international security is promoted by humanising the powerful forces of economic globalisation which are already at work.29

This notion of a cosmopolitan world in which harmony between peoples is the indispensable basis for peace was already familiar in the history of peace thinking. It can be found in the ideas of the Greek Cynics who believed (in words attributed to Diogenes of Sinope) ‘that the only true commonwealth is one which is as wide as the universe’. It may be found too in the cosmopolitan worldview of the Roman Stoics: thus Seneca describes the outline of a commonwealth of humanity which is

A vast and truly common state, which embraces alike gods and men, in which we look neither to this corner of earth nor to that, but measure the bounds of our citizenship by the path of the sun. (De Otio).

Erasmus and his fellow-humanists of the Renaissance were strongly influenced by this aspect of Stoic thought, and argued for what we would now call an internationalist approach to the regulation of human affairs. Juan Luis Vives, in his time as well known as Erasmus, addressed Henry VIII in 1525 with a personal appeal for peace between England and France, ‘My anxiety is great in seeing the Christian world divided by dissensions and wars, and it seems that a perturbation cannot be caused in any part of the world without affecting all the rest.’ Vives went on to argue (De Concordia) that Concord or harmony was both natural and essential to human progress, whereas Discord or war was destructive, materially and spiritually, of all that made life worthwhile. Vives’s proposal for promoting European concord has been described as a precursor of the concept of the League of Nations.

The narrative of peace which extends from the humanists to the Enlightenment increasingly focused on the need for international cooperation which transcended national and even continental boundaries. In an early example, Émeric Crucé’s proposal for a Council of Ambassadors to resolve disputes between states included not only the European states but ‘the Emperor of the Turks, the Jews, the Kings of Persia and China, the Grand Duke of Moscovy (Russia) and monarchs from India and Africa’. In Perpetual Peace, Kant would write that ‘a violation of rights in one place is felt throughout the world’. It followed that ‘the idea of a law of world citizenship is no high-flown or exaggerated notion’.

By the 19th century, a strong theme of liberal internationalism permeates the arguments of peace advocacy (although complicated at times by the conflicting demand for national liberation). As well as emphasising the need for an international legal framework for peace, it has a strong humanitarian aspect – reflected in the foundation of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Much quoted in later years, Victor Hugo’s peroration to the first great Peace Conference (Paris, 1849), conveys the general feeling that national boundaries were being eroded by technological progress, and that this should create a sounder basis for universal peace. The day would come, he forecast, ‘when there will be no battlefields other than markets open to trade and minds open to ideas. The day will come when cannon balls and bombs will be replaced by votes, by the universal suffrage of peoples,’ and by ‘a supreme, sovereign senate’ for the whole of Europe.

The very fact that peace societies, movements and leagues could be formed on a transnational basis, that they could collectively lobby world rulers, sometimes to good effect, and that support for concrete goals such as arbitration and disarmament could be gained, taking advantage of new mass communications, in the populations of many countries, strengthened the sense that peace was now an international enterprise. The rising tide of revolutionary socialism/Marxism, although it rejected what was regarded as bourgeois pacifism, coincided in the sense that it too envisaged action by the proletariat across national borders. The gap between the two was partly bridged at times – notably at the Stuttgart Congress of the Second International (1907) which urged the working class to take strike action against the threat of war.

Bertha von Suttner, the Austrian peace pioneer who played an important part in mobilising support for the 1899 Peace Conference, would sum up the new mood of popular internationalism in her Nobel Peace Prize lecture (April 1906).

We must understand that two philosophies, two eras of civilization, are wrestling with one another and that a vigorous new spirit is supplanting the blatant and threatening old. No longer weak and formless, this promising new life is already widely established and determined to survive. Quite apart from the peace movement, which is a symptom rather than a cause of actual change, there is taking place in the world a process of internationalization and unification. Factors contributing to the development of this process are technical inventions, improved communications, economic interdependence, and closer international relations. The instinct of self-preservation in human society, acting almost subconsciously, as do all drives in the human mind, is rebelling against the constantly refined methods of annihilation and against the destruction of humanity.

|

Bertha von Suttner (1843-1914), Austrian peace campaigner and novelist, the first woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize |

The popular voice for peace: Muffled for ages but never entirely silent, becoming more audible to our ears in the last two centuries, the role of ordinary people in rejecting war and seeking peace has always been present in human society, and was often acknowledged by the peace thinkers who are surveyed here. We hear it in the popular ballads collected for the Chinese Asia-Pacific Journal (Shijing) in which, during the ‘Spring and Autumn’ period (722-403BC) of turbulent warfare, conscript soldiers and their dependants complain bitterly of separation, hardship, the destruction of families and the wasting of their land. In classical Athens where, as already noted, the voices of peace advocates in the Athenian Assembly remain silent in the orthodox history, a popular desire for peace breaks through upon the stage on which, through the medium of comedy, dissenting voices were allowed. In three of the surviving plays of Aristophanes (The Acharnians, Peace, and Lysistrata), we hear the authentic voice of the man and woman in the street when it has not been swayed by pro-war oratory. (The Archanians, an ancient commentary noted, appeals for peace in every possible way’). At the conclusion of Peace, its hero Trygaeus, a very ordinary Athenian but one with more common sense than the generals, celebrates rumbustiously his success in liberating the goddess Peace from the heavenly cave into which she had been cast by War.

Remember, lads, the life of old

Which Peace put in our way:

The myrtle, figs and little cakes,

The luscious fruit all day,

The violet banks and olive groves,

All things for which we sigh,

Peace has now brought back to us,

So greet her with joyous cry!

Medieval Europe is not usually associated with anti-militarism, yet large-scale demonstrations for peace did occur when the populace was driven to protest by the endless round of oppression and war. This popular voice was usually mediated through the accounts of literate clerics who might not always be in sympathy with it, or might exploit it for different ends. In the Peace of God (pax dei) movement of the late 10th to 11th centuries, the Church encouraged popular backing for its attempts to place limits on the marauding greed of warlord nobles who often encroached on ecclesiastical privilege. Thousands of the common folk, we are told by the chroniclers, ‘gathered at assemblies called by the bishops, and ‘cried out to God for Peace, Peace, Peace!’

Non-conformist religious movements such as the Cathars and Albigenses, the Penitents and Flagellants, and (in England) the Lollards, voiced pacifist views although not always consistently, and their voices were also distorted by accusations against them of heresy. The Tenth Conclusion of the Lollards’ manifesto, nailed to the door of Parliament in 1395, was directed against ‘War, Battle and Crusades’. John Wyclif had already criticised the Pope for approving of the Crusades – for the Pope, says Wyclif, may sin as much as anyone else. Medieval literature also offers insights into arguments which countered the dominant values of militarism and chivalry (itself an ambiguous concept). In the words of the Norman cleric Guillaume le Clerc, expressed in his allegorical poem Le Besant de Dieu (1227),

God! how shall a Christian king send forth from his kingdom thirty thousand fighting men, who must leave their bereaved wives and children at home, when they go into mortal combats in which a thousand shall soon be slain and never again see their country, and as many men on the other side.

Popular anti-war sentiment in the age of modern warfare from the 18th into the 19th century was often drowned out by the sound of drums and the display of scarlet uniforms as princely regimes sought to mobilise the populace for cannon fodder. However, with the spread of literacy and modern communications, the Napoleonic Wars initiated a new awareness of the real horrors of armed – and still mostly hand-to-hand – conflict. 19th century writers such as Stendhal (The Charterhouse of Parma), Thackeray (Vanity Fair), Zola (La Débâcle) and, most famously, Tolstoy in his War and Peace, presented an emphatically anti-heroic view of war. The mass media of the 19th century also began to report, though usually in a form biased in favour of the colonial powers, the popular resistance of many colonised peoples. The full extent of such resistance, which typically began with passive and non-violent disaffection but, when suppressed by violence, was likely to become violent in return, is still not sufficiently recognised. (A new book by the historian Richard Gott fills an important gap in this story).30 Gandhi is often credited with virtually inventing the concept of non-violent protest, yet it must have been practiced in many thousands of separate incidents in Europe, Africa and Asia over many centuries.

The popular voice for peace, as we are well aware, has become louder and clearer in the last hundred years although it still can be swayed by appeals to patriotism and chauvinism. Yet from ancient times onwards, peace thinkers have recognised that peace is, in the end, about serving the interests of the people, and that peace is more likely to be secured if the people can be rallied to its cause. Although we live today in very different times, the validity of this proposition is not diminished, and we have seen important (though unfortunately not yet sufficient) results from popular activism against war and nuclear weapons. I could conclude this article with a suitable quotation on the subject from one of the great peace advocates of the modern world, such as Jane Addams, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, Joseph Rotblat, Alva Myrdal, Johan Galtung or Kenneth Boulding. Instead I shall end with a lyric from a popular song of the mid-19th century, often sung in the music halls of Britain. The singer is a young woman, saying farewell to her lover who is going off to the wars, and the last four lines of her ballad, widely quoted at the time by the advocates of peace, convey a simple and still important truth.

When glory leads the way, you’ll be madly rushing on,

Never thinking if they kill you that my happiness is gone.

If you win the day perhaps, a general you’ll be:

Though I’m proud to think of that, what will become of me!

Oh, if I were Queen of France—or, still better, Pope of Rome,

I would have no fighting men abroad—no weeping maids at home.

All the world should be at peace, or if kings must show their might,

Why, let them who make the quarrel be the only men to fight.

(Jeannette’s Song’, c. 1848) 31

|

Marc Chagall, Peace Window’, United Nations Building, New York, 1964 |

*This essay is an expanded version for Asia-Pacific Journal of an article published by the Oxford Research Group. The Narrative of Peace: What we can Learn from the History of Peace Thought’, Oxford Research Group Newsletter, 28 Aug 2012.

John Gittings was chief foreign leader-writer and East Asia Editor at The Guardian, and is now on the editorial board of the Oxford International Encyclopedia of Peace and a research associate of the Centre of Chinese Studies at the School of Oriental & African Studies. After working at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, he began reporting on China during the Cultural Revolution, and later covered major events such as the Beijing massacre and the Hong Kong handover. He has also written extensively on the politics of the cold war and was active in the International Confederation for Disarmament and Peace. He is the author of The Changing Face of China: From Mao to Market (2005) and, most recently, The Glorious Art of Peace: From the Iliad to Iraq (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Recommended citation: John Gittings, “History of Peace Thought East and West: its Lessons for Today,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10 Issue 38, No. 1, September 17, 2012.

Articles on related subjects

> John Gittings, ‘The Conflict between War and Peace in Early Chinese Thought’, Asia-Pacific Journal http://japanfocus.org/-John-Gittings/3725.

> Afghan Peace Volunteers with an introduction by C. Douglas Lummis, An Afghan Okinawa, Asia-Pacific Journal http://japanfocus.org/-Afghan_Peace_-Volunteers_/3758

> Oe Kenzaburo, The Man Who Continues to Speak about Experiencing the H-Bomb — Exposed Clearly: the Deception that is Deterrence http://japanfocus.org/-Richard-Minear/3511

> Nakazawa Keiji, Hiroshima: The Autobiography of Barefoot Gen http://japanfocus.org/-Nakazawa-Keiji/3416

> Yuki Tanaka, War and Peace in the Art of Tezuka Osamu: The humanism of his epic manga http://japanfocus.org/-Yuki-TANAKA/3412

> Ahagon Shoko and C. Douglas Lummis, I Lost My Only Son in the War: Prelude to the Okinawan Anti-Base Movement http://japanfocus.org/-Ahagon-Shoko/3369

> C. Douglas Lummis, The Smallest Army Imaginable: Gandhi’s Constitutional Proposal for India and Japan’s Peace Constitution http://japanfocus.org/-C__Douglas-Lummis/3288

Notes

1 Lawrence Freedman ed., War (Oxford Reader), (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 7.

2 John Keegan, A History of Warfare (New York: Random House, 1993), 3.

3 Patrick M Cronin ed., Global Strategic Assessment 2009: America’s Security Role in a Changing World (Wahington: Department of Defense, 2009), 145.

4 Thucydides, History, Book 4. 62 (my translation).

5 John Gittings, The Glorious Art of Peace: from the Iliad to Iraq (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

6 David Barash, ed., Approaches to Peace: A Reader in Peace Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

7 Barbara Tuchman, The Proud Tower: A portrait of the world before the war 1890-1914 (New York: Macmillan, 1965), ch. 5, 229-88.

8 ‘Adam Curle’, The Guardian, 4 October 2006

9 See further Alexandru Balas, Andrew P. Owsiak, Paul F. Dieh, ‘ Demanding Peace: The Impact of Prevailing Conflict on the Shift from Peacekeeping to Peacebuilding’, Peace and Change, 37:2, April 2012, 171-194.

10 See for example the output of The Economics and Security Journal, launched in 2006, which addresses issues related to the political economy of peace and security, with special emphasis on ‘ constructive proposals for conflict resolution and peacemaking’.

11 See further the special issue on peace education, Peace and Change, 34:4, October 2009.

12 The Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame claims to have produced more than 1,200 graduates who now work ‘at all levels of society to build a more just and peaceful world’.

13 Charles F Howlett ‘Peace History Society’, in Encyclopedia of Peace Education (online, 2008).

14 Li Shijia, ‘Harmonious World: China’s Ancient Philosophy for New International Order’, People’s Daily (online), 2 October 2007.

15 The Iliad, trans. E. V. Rieu, ed. Peter Jones (London: Penguin Books, 1993), xxxiv.

16 I have identified no less than six points in the narrative of the Iliad where Homer holds out the possibility of an end to the war. One of the most striking occurs in Book 2 where the entire Greek army turns its back on Troy and rushes to the boats to embark for home – their desire to abandon the war is only foiled by divine intervention! See further The Glorious Art of Peace 42-44.

17 Plutarch, Greek Lives, trans. Robin Waterfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), ‘Nicias’, 193.

18 A number of US scholars have re-assessed with insight Greek history and drama in the light of our experience of modern warfare, comparing aspects of the Peloponnesian War with the Korean and Vietnam Wars. They include the Vietnam veteran Lawrence Tritle, From Melos to My Lai: War and Survival (London: Routledge, 2000); Robert Meagher, Herakles Gone Mad: Rethinking Heroism in an Age of Endless War (Northampton, Mass.: Olive Branch Press, 2006); Jonathan Shay, Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character (New York: Scribner, 1994); and David McCann and Barry Strauss, eds., War and Democracy: A Comparative Study of the Korean War and the Peloponnesian War (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2001).

19 ‘The Conflict between War and Peace in Early Chinese Thought’, Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 16 March 2012. For analysis of the Book of Songs and the Chronicle of Zuo, see The Glorious Art of Peace, 47-53.

20 For a classic study of Erasmus and his fellow-humanists, see Robert P Adams, The Better Part of Valor: More, Erasmus, Colet, and Vives, on Humanism, War, and Peace, 1496–1535 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1962).

21 Tolstoy’s Sevastopol reports are translated in Louise and Aylmer Maude, trans., Tales of Army Life (London: Oxford University Press, 1933).

22 Peter Brock, Pacifism in Europe to 1914 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972).

23 Augustine, City of God, 19: 13, trans. Marcus Dods, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, 1st series, vol. i (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1887).

24 Charles Darwin¸The Descent of Man (1871), ch. 4.

25 J. Novikow, War and its Alleged Benefits (London: Heinemann, 1912); Jan Bloch [Jean de Bloch], The Future of War in its Technical, Economic and Political Relations (Boston: The World Peace Foundation, 1914).

26 Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert, Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (1751–72), vol. xi, online at http:/fr.wikisource.org/wiki/L’Encyclopédie (my translation).

27 The Praise of Folly and Other Writings , trans. Robert Adams (New York: Norton, 1989), 105-6.

28 Chris Abbott, Paul Rogers, and John Sloboda, Global Responses to Global Threats: Sustainable Security for the 21st Century (London: Oxford Research Group, 2006).

29 Ken Booth, Theory of World Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

30 Richard Gott, Britain’s Empire: Resistance, repression and revolt, (London: Verso, 2011).

31 ‘Jeannette’s Song, You are going far away’, words by Charles Jefferys, music by Charles William Glover, c. 1848. This is the first song in a set of four published as The Conscript’s Vow. Its second verse is reproduced here.