Between 2012 and 2014 we posted a number of articles on contemporary affairs without giving them volume and issue numbers or dates. Often the date can be determined from internal evidence in the article, but sometimes not. We have decided retrospectively to list all of them as Volume 10, Issue 54 with a date of 2012 with the understanding that all were published between 2012 and 2014.

Roger Pulvers

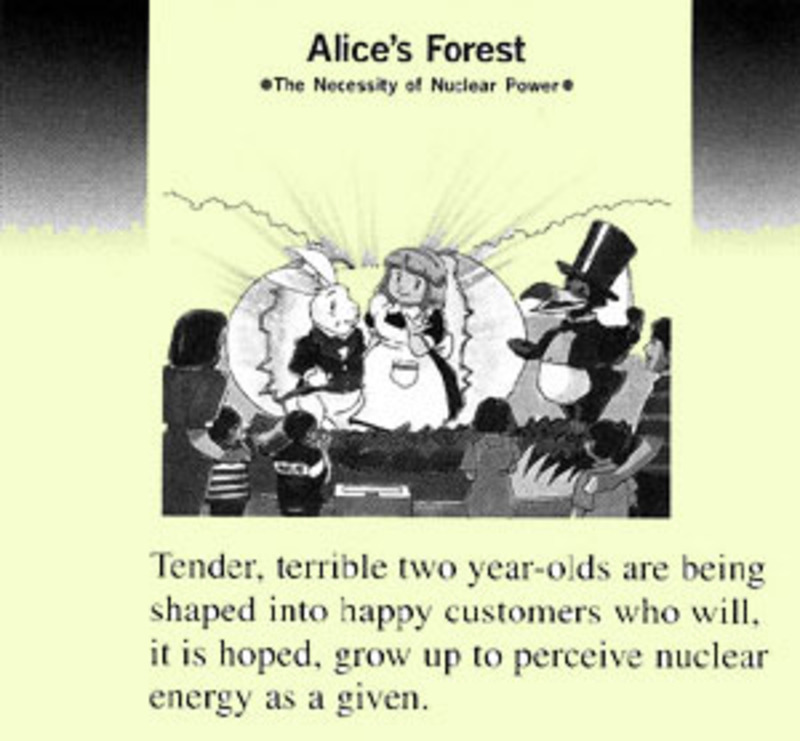

If you visit the Alice Pavillion at the Shika nuclear power plant in the town of Shika, Ishikawa Prefecture, you will be happily entertained by Prof. Aomushi (Blue Caterpillar), who, water pipe in mouth, sits in the sun and, together with Alice, “teaches you about radiation.”

Illustration by Walderedo de Oliviera

What those friendly cartoon characters will not teach you, though, are facts about the geological fault that, in all likelihood, is active under the plant’s No. 1 reactor.

The government gave Hokuriku Electric Power Co. — the plant’s owner and operator — the go-ahead to start construction in 1988, “after (the company’s) underground surveys did not detect any active faults.” The No. 1 reactor was commissioned in 1993, and a second reactor went on line in 2006.

Shika Nuclear Power Plant

Now research has shown a “strong possibility” that the fault lying below the older reactor may be active. Another fault lies below No. 2 reactor as well. By law, nuclear power plants built over active faults are not permitted to operate — yet Hokuriku Electric is determined to restart these reactors despite local opposition due to real safety concerns.

It is not only the utility companies operating Japan’s nuclear power plants that are pushing for a return to the status quo ante as it was prior to the nuclear disaster that followed the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011. The dominant industrial forces, led by the giant electric power companies, are actively lobbying for the restart of reactors as well.

Nothing could have illustrated this more vividly than the Oct. 3 visit by Yonekura Hiromasa, chairman of Nippon Keidanren (Japan Business Federation), Japan’s most powerful business organization, to the Hamaoka Nuclear Power Plant in the city of Omaezaki, Shizuoka Prefecture.

Yonekura, who has been president of Sumitomo Chemical Co. Ltd. since 2000, was accompanied on his first ever visit to a nuclear plant by Kojima Yorihiko, vice-chairman of Keidanren and chairman of the board of directors of Mitsubishi Corp. (The Articles of Sumitomo Chemical list, as an “Objective of Management,” “the nuclear power industry,” for which they provide a range of goods and services; while among Mitsubishi Corp.’s “Main Products and Services” is the “transport and import of nuclear fuel.”)

“I was extremely relieved to see,” said Yonekura, “that safety (at the plant) is steadily being strengthened.” He went on, “If we could win the trust of the residents and restart the plant, it would be a role model for the world.”

The safety he alluded to is in the hands of owner and operator Chubu Electric Power Co., which, in May 2011, was forced by Prime Minister Kan Naoto to shut down the Hamaoka plant because its safety could not be guaranteed. Yonekura was “relieved” when he saw the construction of an 18-meter-high sea wall, to be completed by December 2013 at a cost of ¥140 billion.

But the plant sits right over the subduction zone where two tectonic plates come together. It is a toss up of chance involving potential catastrophe as to whether the plant’s reactors could survive the expected massive Tokai earthquake, and whether this new sea wall could stand firm and repel an accompanying tsunami.

Yet, the industrial and financial interests that dictate public policy to politicians and bureaucrats are determined to forge ahead.

Consider this: On Oct. 3, the day of the Keidanren visit, national broadcaster NHK displayed a map on its 7 o’clock evening news program. The map had a number of circles on it, each with a radius of 50 km — and each representing the area that would be contaminated by radioactivity from a crippled reactor. The circle with the Hamaoka plant at its center encompasses the largest population of any plant in Japan: 2.14 million people — though of course radiation from there could well track north to Greater Tokyo, with its population of more than 35 million. What then for Yonekura’s sense of “relief”?

However, Tokyo is by no means only endangered from the south. Around 100 km north of the capital stands the Tokai Nuclear Power Plant in Tokai Village, Ibaraki Prefecture. It was months after the Fukushima disaster before events that occurred at the plant’s No. 2 reactor on March 11, 2011 — the day of the Great East Japan Earthquake — came to light.

In fact it turns out that one of three pumps installed for cooling the reactor was inundated by a tsunami that reached 5.4 meters. If it had risen another 70 cm, it would have knocked out the other two pumps as well. It was simply good luck that work to raise the height of the sea wall to 6.1 meters was completed on March 9.

If a similar accident to that at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant had struck the Tokai reactor, airborne plumes of radioactive substances may very well have shrouded Tokyo.

Yet as Otani Norio, the mayor of Nasukarasuyama City in neighboring Tochigi Prefecture, said recently, “It was only in February of this year that I learned of just how dangerous the situation at Tokai No. 2 was in March 2011. Nasukarasuyama is a mere 37 km from it. … It sent shivers down my spine.”

But Shika, Hamaoka and Tokai are just three examples of nuclear plants highly vulnerable to catastrophic accidents.

Leaders of the governing Democratic Party of Japan have been issuing conspicuously ambiguous statements as to who will take the decisions on whether to restart nuclear plants or not — and when, if ever, nuclear power will be phased out, with 2039 indicated as the date for closure. For its part, earlier this month the Nuclear Regulation Authority, which is an administrative body of the Cabinet, outlined a number of “nuclear disaster prevention measures,” such as expanding “priority areas for emergencies” to 30 km, distributing iodine pills to stave off the effects of radiation exposure in thyroid glands, evacuating hospitals, etc.

While these measures may be necessary in case of an accident when reactors are being decommissioned, they give a false sense of security to people regarding the operation of nuclear power plants.

This, though, is the strategy of Japan’s political leaders, bureaucratic controllers and industrial forces: Confuse the public with ambiguous signals, feigning an interest in opposition arguments; issue guidelines that assuage public anxieties; and send the captains of industry out to assure the people that their welfare — not instinctive greed — is their primary concern.

If a major earthquake or tsunami, or both, strike a reactor at the Shika, Hamaoka or Tokai nuclear power plants — or ones at any of the many other nuclear plants built on precarious sites — and radioactive contamination spreads through the population, what will be the response of the politicians, bureaucrats and business leaders then?

They are trying once again, as they did in the 1950s and ’60s, to railroad policy in favor of nuclear energy while maintaining the pretense of openmindedness, debate and concern. But renewal of nuclear power in Japan is not the fait accompli it was decades ago.

If we do go back to pre-Fukushima norms, we will only be flirting with disaster and possibly poisoning not only ourselves but also our children, their children and who knows how many others beyond these shores. The only legacy of such a policy is the legacy of death.

Those who believe the assurances of a blue caterpillar and Alice concerning “the facts” about radiation are living not in Japan, a country plagued by natural disasters, but truly in a Wonderland. In such a Wonderland, myths reign supreme and bias is dictated as simple truth from above.

Now is the time for all of us to wake up, come back to Earth and refuse to allow the powers-that-be to force us to live in a world that does not resemble our own.

This is a slightly supplemented version of an article appeared in the Japan Times on October 21, 2012.

Roger Pulvers is an American-born Australian author, playwright, theatre director and translator living in Japan. An Asia-Pacific Journal associate, he has published 40 books in Japanese and English and, in 2008, was the recipient of the Miyazawa Kenji Prize. In 2009 he was awarded Best Script Prize at the Teheran International Film Festival for “Ashita e no Yuigon.” He is the translator of Kenji Miyazawa, Strong in the Rain: Selected Poems. The Dream of Lafcadio Hearn is his most recent book.