[Ed. Note: This article is part of an ongoing series and online exclusive exploring contemporary artists through interviews, commentary, and visual engagements provided by art historian Asato Ikeda. For other interviews in this series, see “Art and Politics with Asato Ikeda.“]

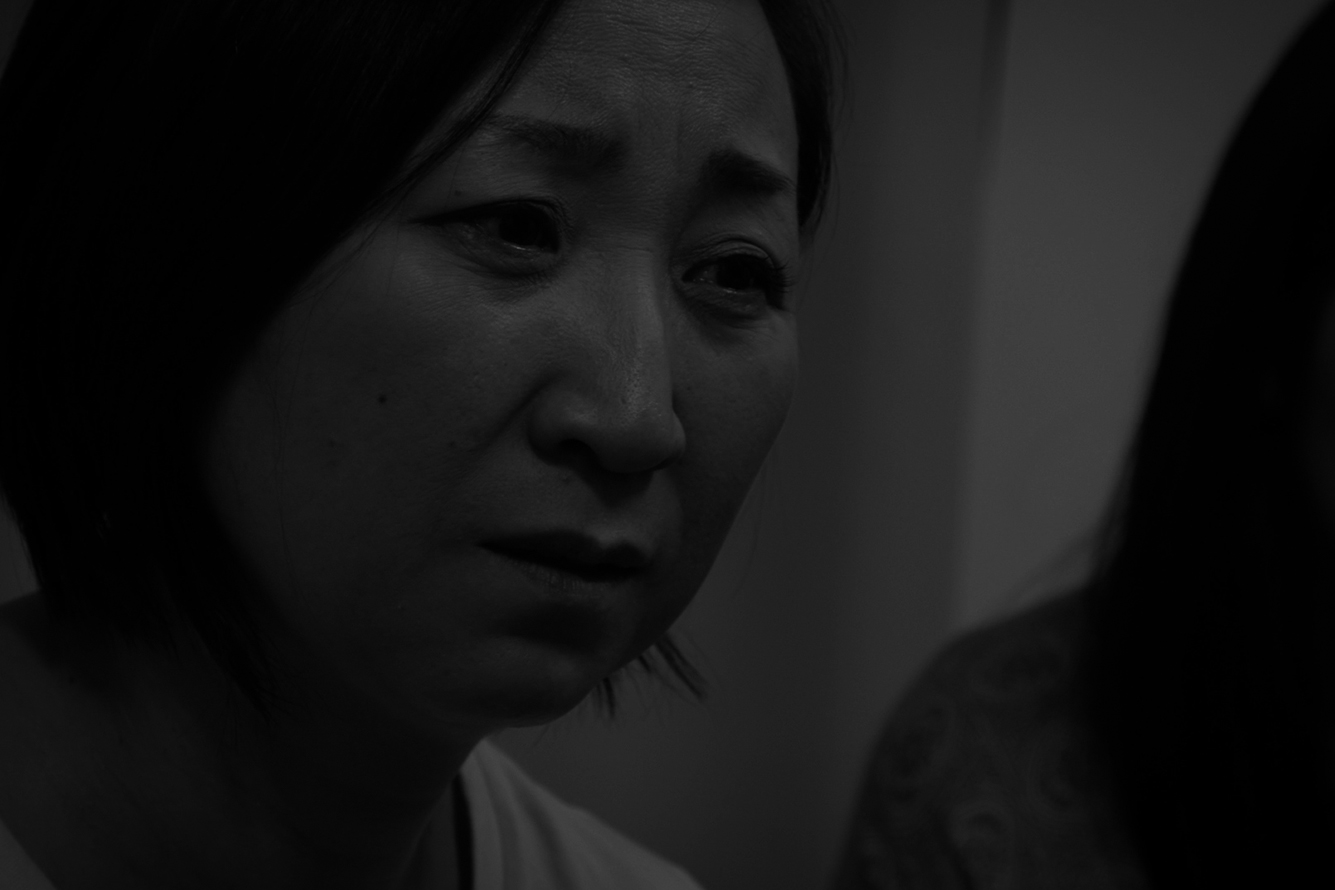

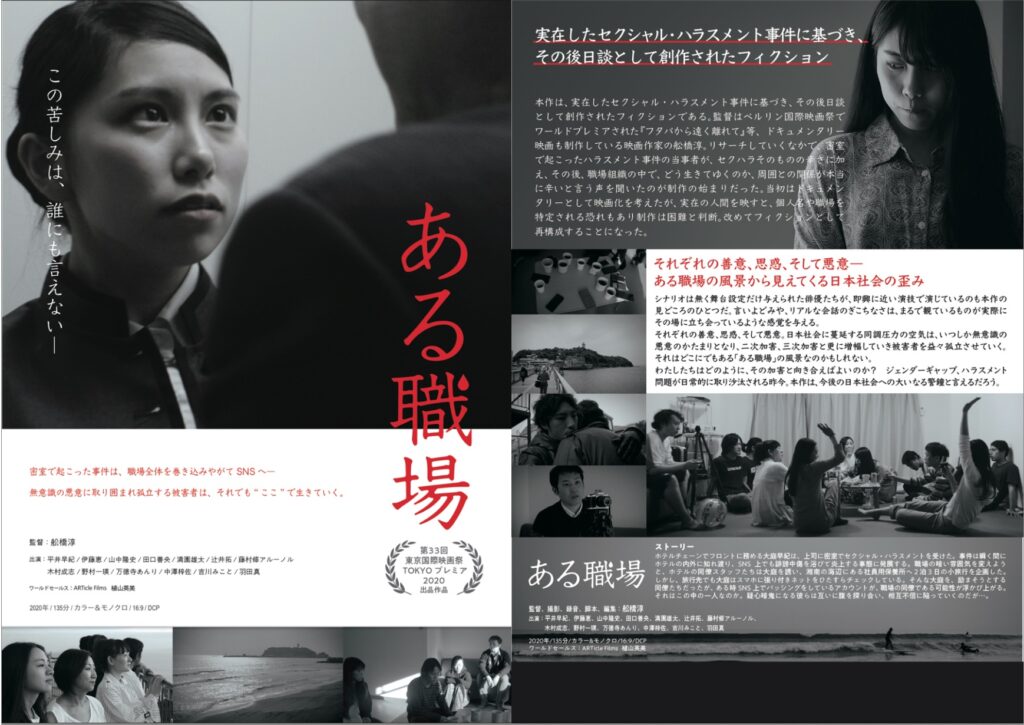

Abstract: In this conversation with Asato Ikeda, Atsushi Funahashi discusses his 2022 film Company Retreat, which is fiction based on a true story.1 The film tells the story of a female employee Saki who works at a hotel and was sexually harassed by her boss. The story unfolds in Kamakura, where she and her co-workers have an emotional company retreat where their differing opinions about the sexual harassment incident collide. The film centers on the secondary trauma and harassment that survivors often encounter in Japan and elsewhere.

Keywords: Japan, film, sexual violence, gender relations, harassment, education

Atsushi Funahashi (b. 1974) is a Japanese film director. Originally from Osaka, he graduated from the University of Tokyo with a B.A. in cinema studies and studied film directing at the School of Visual Arts in New York. His representative works include Big River (2005), Nuclear Nation (2012), and Company Retreat (2022), and his films have been screened at major international film festivals, including Berlin, Annonay in France, Pusan, Shanghai, Sao Paolo, and Tokyo.

Ikeda: Thank you for making the time for this today. I re-watched Company Retreat for this interview a few days ago, and I’m still struck by how uncomfortable the film made me. As somebody who grew up in Japan, I remember how human relationships there can be convoluted in a particular way. There are certain very abstract phrases that are often used in Japan, such as “you are relying too much on other people” (amaeteiru), “you must work hard” (ganbatte), “we are a team” (nakama dakara),” or “don’t run away” (nigenaide). I am working on collaborative research on NHK data regarding sexual violence and consent with other researchers, but the survivors’ voices there are isolated from the cultural context.2 I thought your film did a great job presenting that context—the dark aspects of Japanese culture—though I am having a hard time articulating exactly what they are. Perhaps narrow-mindedness and herd/village mentality? I know you talked about the goal of your filmmaking as capturing the “unconsciousness of the times” (jidai no muishiki), which might be relevant here. Would you like to elaborate on this?

Funahashi: There might be many answers to this question, but I often talk about how there is no education in Japan that allows people to have debate. They cannot debate. I think they take things personally. In our East Asian culture, the hierarchical thinking—the idea that we cannot challenge somebody in a higher position— is deeply ingrained in our unconscious. There are cultural codes about how we are expected to behave toward our boss (jōshi), the senior (senpai), and the junior (buka) and to be mindful about that relationality. When somebody “lower” than you speaks in a certain way, you get to think “how dare you talk like that” and that emotional reaction comes first. That cultural code prevents us from having a frank “debate” about something on an equal level. You are supposed to “read the air”—the hierarchy among people.

When I was in New York and I worked on the NHK production team for a show called “New Yorkers.” For a special episode on American education, I went to an elementary school in Brooklyn. Everybody raises their hands when their teachers ask if there are any questions and they grow up like that. When I went to a Japanese elementary school, first and second graders usually raise their hands, but around third and fourth grades, the students stop raising their hands. They will start looking around and see if it is okay to raise their hands or speak up and say certain things. For fifth and six grades, nobody raises their hand and there is only silence. That moment of silence where everybody is looking around trying to “read the air” is quite unique to Japan, I think. It is the culture of “hirame-kyorome,” referring to somebody who only looks upwards at “superiors” and sideways at “equals,” not caring to see people “below” or “inferiors.”

The underlying problem regarding sexual violence in Japan is this basic inability to have debate. When sexual harassment happens, there is no clear debate about what caused it. In addition to the lack of practice of debate, sexuality is a complex and sensitive issue to begin with, and sexual violence becomes a topic that people cannot discuss for multi-layered reasons. So consequences or narratives of sexual harassment get decided by people on “the top” and everybody else has to follow them without questioning. And often the understanding of sexual violence or harassment by those people in senior management positions has not been updated, so I can see how this could easily become a problem.

Ikeda: I agree. Asking questions is often seen as being naïve or even stupid as you are supposed to know the answers, but you don’t. The hierarchical relationality among people and appropriate behavior accordingly often become the most important thing to think about, and discussions do not lead us to fully understanding ideas or clarifying points. Also, in Japan people are not trained to question authorities or criticize institutions. Your film Company Retreat is about secondary victimization. If the company had processed the sexual harassment incident properly to begin with, there wouldn’t have been any confusion, suspicion, or ambiguity among the colleagues, but there was no consensus on it being the company that was to blame.

Funahashi: American society has a lot of problems too, but if there is something I think is a good practice and needs to be introduced to Japan more fully is the system that protects whistleblowers. When there were many cases of bribes and corruption in the 1990s, they created a structure to protect whistle blowers with the belief that whistle blowers’ actions are to the benefit of the company. I have seen an American company that treated sexual harassment cases under the policy of whistleblowing. When the incident happened, the company guaranteed employment to the woman while the investigation was in process, and she was isolated and could be only reached indirectly through liaison. This treatment prevented her from being the target of retaliation or harassment from those involved or other people at the workplace. For the victim, continuing to work in the same workplace after harassment means they could be the target of second and third victimization. The underlying belief here is that the company benefits from this process by providing a safe workplace to employees and it’s the company’s responsibility to protect the human rights of the victim. Most Japanese companies do not think this way. They are about twenty or thirty years behind their American counterparts.

Ikeda: The recent Fuji TV scandal might be the beginning of that movement. I would like to ask you questions more specifically about the film now. In other interviews I read you saying that you initially wanted to make a documentary out of this case but failed. I understand that this film is a fictional work based on a true story. Is it possible for you to talk about what part was a fiction and what part was based on the true story? For example, I liked that in the film the company retreat happens at Kamakura—since I recently visited the site a few weeks ago—and this gloomy retreat was contrasted against the “good vibes” of the surfers in the sea.

Funahashi: Around 2016, there was a case of sexual harassment at a franchise hotel that I heard about from my friend . A woman who works at the hotel front was harassed by her boss in the same department. At first, I wanted it to be a documentary. I was introduced to those involved by my friend and I got permission to do the interviews with the initial agreement that I would not report this publicly. I brought only a pen and a notebook—without a camera—to hear their stories, including those of the victim and perpetrator, along with those of their colleagues, and those working in a different hotel, since the incident had spread as “rumors” to an extensive group of people. I felt a strong impression when the victim said it was hard for her to experience sexual harassment, but it was as hard to continue working and living in the same workplace. She became the target of defamation (hibō chūshō), and the hotel did not do anything about it. She was transferred to a different department, but the reason was never clarified openly to others. After the interview, I asked the victim if it was okay to bring in a camera and do the shooting. She said no because even if her face is blurred, people might be able to tell it’s her.

Ikeda: Was this case relatively known in the online world? The film touches on cyber-bullying.

Funahashi: No. There is not much about this case online. The defamation was primarily at her workplace. The bullying on social media in the film was a fictional part of the work. After the interview, I asked her why she allowed me to interview her. She said because she didn’t want this to happen again and if talking about this would help others she wanted to do it. So we thought of ways in which we could still produce a film about this and the answer we came up with was substantially fictionalize the incident so that their names or locations would never be inferred. The victim and others involved then gave us permission.

Ikeda: I read in other interviews about how the lines in the conversations in the film were not scripted beforehand and you had the actors improvise them. How did that process work?

Funahashi: Talking about sexual violence inevitably brings out very different opinions, and I understood from the start that it was a complex and sensitive topic. The biggest problem for me, honestly, was that I was a male director. At first, I thought, maybe I shouldn’t be the one directing this film. I thought perhaps I could co-write the script with a female writer and then let her direct it. But many people told me: you’re the one who directly interviewed all these people involved in the incident, you’re the one who probably feels the most committed to the story—so you should direct it.

So I decided to direct, but I didn’t want to be the “mastermind” of the story. Usually film directors tell a story or communicate a message through the mouths of their characters. But in this film, I asked the actors—especially the female actors—to express their own opinions. I set the broad framework for the scenes, like swimming on the beach, sightseeing, eating together, and the topics of conversation, and I also set the positionalities of the characters. But what they would actually say, and how they would say it, I left to them.

We spent a long time shooting. There were hours of conversations, many of them quite boring, that I couldn’t use at all. But sometimes, in those unscripted conversations, I would capture something compelling—spontaneous interactions among the actors while they were in character. And we painstakingly built on those.

So the characters in the film: There’s Saki, the victim. There’s Ms. Kinoshita, who wants to “protect” Saki. There’s another woman in a higher position, who also experienced sexual harassment in the past but feels that Saki is making too big a deal out of her case. There are men who are sympathetic in some ways but also doubt the severity of what happened to Saki. And then there’s a gay couple—two men—who care deeply about their own sexual minority status, but don’t care very much about the hardship Saki is going through.

That gay couple was meant to reflect an atmosphere in Japan where even a marginalized group, like gay men, may still try to ostracize someone like Saki, who is seen as “disturbing” social harmony.

Ikeda: I found the presence of that gay couple very interesting, because I felt it reflected a broader cultural context in Japan—where gay men are often more socially accepted than women. Misogyny seems to be more prominent than homophobia. I, of course, watched the film as a woman, and I wonder how male viewers might have watched it. I would assume that the fact that they were watching the film at all meant that they already had a higher awareness of sexual violence as a social issue.

Funahashi: Actually, not necessarily. And this might sound strange, but have you seen the poster of the film? Some men came to the theater expecting my film to be pornography.

Ikeda: What? How? Even though they already knew the story? …Actually, I understand that. I am analyzing narratives from the NHK survey, and sometimes they border on porn. This is because there isn’t much difference between some titles of Japanese porn—like “I raped my sister’s friend”—and what is actually happening in reality. The narratives written by survivors that I read in the NHK survey could be used as pornography if they fell into the hands of the wrong audience.

Funahashi: Most of the male audience members were serious. They came alone, they watched carefully, and some even spoke to me afterward at autograph sessions on weekday nights. But maybe about ten men came expecting it to be porn. That was really shocking to us too. There is a very short harassment scene in the film where Saki is confined to a room and her boss locks the door. And there were men who made strange noises during that scene, obviously getting excited.

Ikeda: That is really dangerous. Because even the NHK survey narratives could be sexualized for somebody’s pleasure. There’s so much porn that depicts women being harassed. And as many survivors have pointed out, some perpetrators are actually inspired by that kind of porn. For them, it becomes a sexual fantasy.

Funahashi: Exactly. Our brains have been contaminated by pornographic videos and also by anime and manga. If you look at the poster for the film, it shows Saki—a young woman—looking troubled, standing next to an older man whose face you cannot see. And the poster has the line, “I cannot tell this suffering to anybody”(Kono kurushimi wa darenimo ienai).

Some men—maybe not a majority, but still—looked at that and fantasized about what might come next. They came all the way to the theater with that fantasy in their heads. That was something we absolutely did not expect.

Ikeda: Returning to male audiences more generally, I wonder if there were some who sympathized with the things said in the film by male characters who basically undermined Saki’s suffering.

Funahashi: Yes, absolutely. There are so many men whose understanding of sexual violence has not been updated. Some of the male employees I interviewed for this film said they thought the victim was overreacting, that she had gone too far.

I did those interviews around 2016 and 2017. And that was the same period when Aso Tarō, who was then the Finance Minister, publicly said, “there is no such thing [crime] as a sexual harassment charge.” I thought that was such a revealing line—one that perfectly represents the misogyny of Japanese society. So I had one of the male characters in the film say that exact line. I pulled real-life lines like that, things actually said by men, and used them in the film to capture the patriarchal nature of the society.

Ikeda: I’d like to dig a little deeper into something you said earlier about being a male filmmaker, and how you felt you might not be the most appropriate director of this film. Since the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 in the United States—and especially in academia—there has been a strong emphasis on being mindful of one’s positionality: race, gender, sexuality, class, economic background, and so on. It has become a necessity to take these into account. Having heard your statement about positionality as a male director, I wonder if the same kind of awareness and change is happening in Japan as well. I wouldn’t know, since I don’t work in Japan.

Funahashi: In the Japanese film industry, since March 2023, there have been several cases of male directors—like Sono Sion, for example—making headlines because of sexual harassment. My film Company Retreat was released around that same time. There were confirmed cases of directors using their power for sexual gain under the excuses of “casting” or “rehearsing.” These cases made big news.

In response, there are ongoing efforts to eradicate sexual harassment in the industry. With directors like Kore-eda Hirokazu and Nishikawa Miwa, I helped found an organization called Action 4 Cinema that works to fight sexual violence in the industry. We produced a handbook and distributed it widely. We asked people to attach the handbook to film scripts so that everyone on set would have to read it. The handbook includes resources for people who have experienced violence, and it also asks crews to designate people on the ground who would be responsible for handling such matters. Efforts like this, aimed at making the structure of power visible, are happening in different places. So yes, I do think some change is happening—but at the same time, there is still so much that hasn’t changed.

Ikeda: That’s really good to hear. I was very struck by what the victim you interviewed for this film said about why she talked to you: that she did not want this to happen again to anybody else. That line is the same one most survivors use when they explain why they participated in the NHK survey. They say, “I don’t want this to happen to others.”

For the research collaboration on that survey, I’m working with anthropologists and labor economists, but I’d really like to also work with psychologists, activists, lawyers, and people from other fields. Sexual violence—like war, pandemics, or climate crisis—is a topic that really needs an interdisciplinary point of view. I am the only person in cultural studies on the team, and I keep wondering what people in the cultural industries can contribute to this discussion. How can we best add to the conversation? What can we do that people in other fields cannot do?

Funahashi: I think one of the most important things we can do is visualize best practices and create training programs for different industries. For example, we could produce a drama about how an institution can best handle a sexual violence incident. We could visualize what good scenarios look like: how to protect the survivor, how to penalize the perpetrator. Because the truth is, institutions don’t really know what best practices are supposed to look like.

And training programs, I think, should focus on the feelings of people on the receiving end. For example, it’s hard for famous filmmakers—people with power—to really imagine what it feels like to be yelled at, or belittled, or harassed. But young people today have no tolerance for those kinds of behaviors, and them quitting has become a serious issue.

Ikeda: That sounds like a great idea. At my university, we actually have a training program that addresses harassment and discrimination, so I can definitely see the value of visualizing good practices through film. To conclude this interview, could you tell us about your current project?

Funahashi: It’s not directly related to harassment. Right now, I’m working on a film about euthanasia. It’s another “taboo” topic that Japanese society doesn’t really want to talk about. In Japan, most of the discussion is about how to prolong life, not how to bring it to an end. But in other countries, it’s a different story. In England, an assisted dying bill is now being passed. In Spain and Canada, such laws have already been passed. Taiwan is proactively discussing it. Japan will probably be the slowest country in East Asia to confront this issue.

And again, for me, this connects back to the same problem we’ve been talking about—the inability to debate. This is very much a reflection of the “unconsciousness of the times.” In Japan, people simply do not want to discuss this topic, while the rest of the world is already having the conversation.

Ikeda: Through our discussions of sexual violence and other difficult topics, I think both of us are working on issues that many people in Japan generally do not want to talk about. But I also want to acknowledge our positionalities. We are both Japanese, but both educated outside Japan, which gives us a kind of “safe space” even when we’re criticized back home. The claustrophobic feeling I had watching Saki—the victim in your film—came from the fact that she did not have such a safe space. She was stuck in her community, and she didn’t have the option of leaving.

Funahashi: In Japan, a sense of insularity (heisokukan) is ingrained in us through education and culture. So when people feel cornered, often the only option they see is suicide. They could leave their community if things are not working, but the idea of “leaving” doesn’t even occur to them.

Unless education itself changes in a way that brings these unconscious patterns into awareness, nothing will really improve. Of course, culturally, there are also positive sides to this shogi-like way of thinking—where you keep working things out step by step, closing in logically, carefully. That’s why the Shinkansen arrives exactly on time, why a long-distance train can stop at a station without being off by even one minute. Everything is done with incredible precision and care. And that’s admirable.

But if you apply that same mindset to every part of your life, it becomes suffocating. It produces a stifling society where people corner themselves. When they can no longer function in an organization, they stay trapped in that narrow shogi-like logic. And once they conclude that they’ve committed some kind of offense, it can very easily lead to suicide. This narrowing of perspective is, I think, something deeply rooted in Japanese culture.

But we shouldn’t just dismiss it as a cultural issue. We have to recognize it as a social problem. And the only way to address it is through education. Personally, I think students should be required to spend a few years outside Japan—two or three years—to acquire a broader perspective.

Ikeda: Thank you very much for sharing your thoughts today. I really appreciate it.

Notes:

- The film is currently available on Amazon Prime in Japan but not for streaming outside the country.

- Other members of our research team include Machiko Osawa, Akiko Takeyama, David Slater, Maiko Kodaka, and Evan Koike. We plan to publish our findings in Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus at a later date. For further information on the NHK data, see https://www.nhk.or.jp/minplus/0026/topic059.html.