[Ed. Note: This article is part of a collection of essays entitled “Critical Reflections on the 80th Anniversary of the End of World War II” published in August 2025.]

In 2019, Kurihara Toshio began a new serial column for his newspaper, the Mainichi Shimbun.

A veteran reporter, Kurihara had carved out a name for himself as a leading journalistic voice covering the history and memory of the Asia-Pacific War in Japan. He dedicated his new column to delving deeper into these topics, but with a particular focus on the redress movement of Japan’s air raid survivors. Rather than focus on the hibakusha, survivors of the atomic blasts in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Kurihara fixed his attention on air raid survivors in his own backyard, Tokyo.[1]

This was a full-time beat. For months, Kurihara shadowed this dogged but dwindling community of memory activists. Children during the war, these retirees now dedicated the twilight of their lives to memorializing air raids in Tokyo that had been relegated to the margins of national memory. Their aging bodies showed few signs of slowing their crusade. Kurihara tracked them all over the city, filing stories on everything from court cases to legislative petitions to public outreach.[2]

His newspaper colleagues, accustomed to reading articles of this sort only around the anniversaries of surrender and the atomic bombings each August, had previously joked that his reporting “looked like summer all year long.”[3] Kurihara leaned into the remark, christening his column the “Perpetual Summer Report” (Tokonatsu tsūshin).

The column itself is a riveting tour of the shifting memoryscape of Tokyo, a city subjected to over a hundred air raids in the final year of the war, including five ruinous firebombings. It takes readers to the statue of Saigō Takamori in Ueno Park, showing how this well-known landmark, a favorite meeting spot for cherry-blossom viewers today, presided in the spring of 1945 over one of the city’s largest open-air crematoriums. It trails gray-haired activists during their weekly “kōnnichiwa katsudō” in front of the National Diet, leafleting operations designed to raise awareness among both politicians and the public. (“Do this in front of the U.S. Embassy!” scolds one passerby in a telling exchange.) Kurihara’s column offers a deeply reported postwar history of the Tokyo air raids, a reminder that while the air raids may have ended long ago, the damage they caused has not.[4]

But the Perpetual Summer Report is something more. An astute observer of the war memory beat in Japan, Kurihara does not shy away from training his critical lens on his own industry. He is the rare World War II journalist to report on World War II journalism. Not only in his column, but also in interviews, lectures, and now a brand new book, Kurihara has offered critical commentary on the limits and possibilities of World War II journalism eight decades on.[5]

In this, Kurihara is joined by a small but growing group of scholars concerned with what media observers have dubbed Japan’s “August journalism” (Hachigatsu jānarizumu): the tendency for ritualized, compressed, and hollowed-out coverage of war memory each August. To Kurihara’s analysis of contemporary journalistic practice, media scholars have added path-breaking studies of the historical construction of Japan’s season of remembrance. Satō Takumi, a media historian at Sophia University, has carefully considered the myth-making surrounding the spectacle of August 15, the very cornerstone of national memory.[6] Yonekura Ritsu, a media scholar at Nihon University, has more recently compiled a vast audio-visual archive of memorial coverage to map the prevailing storylines of August journalism across the postwar period.[7]

Their work carries special salience in August 2025, a year that marks the 80th anniversary of Japan’s defeat. At a time when media outlets the world over are carrying special features on “the end of World War II,” these scholars are asking a different but vital set of questions about what it means for a conflict so far-reaching and so destructive to actually come to an end.

What are the hallmarks of August journalism and how did it emerge? How should we understand the potential perils of and alternatives to these mediated rituals of World War II commemoration? What can journalists and scholars beyond Japan learn from a critical examination of its season of remembrance? This essay explores these and other questions by way of a brief survey of this dynamic arena of media criticism—what could be called the burgeoning field of “August journalism studies.”

Requiem of August

August brings in Japan not only the observance of Obon, Buddhist rituals honoring the spirits of one’s ancestors, but the anniversaries of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Emperor’s surrender broadcast—8.6, 8.9, and 8.15. As if by reflex, Japan’s major news outlets spring into war memory mode. A wave of special programs, documentaries, and editorials dedicated to these commemorations wash across front pages, tv screens, and social media feeds. NHK and other broadcasters air live coverage of the atomic bomb memorial events and the noontime 8.15 “end of war” ceremony, a somber moment of reflection that brings the country to standstill.

And then, as quickly as the tidal flood of remembrance rushes in, it recedes—gone until another year.

Critics of August journalism don’t take issue with these acts of national reflection on their own. No one disputes the inherent value in bearing witness, praying for peace, or reaffirming Japan’s commitment to non-aggression. In a media environment crowded with distractions, these August anniversaries have provided a vital outlet for Japanese across generations to take stock of the ravages of war.

Their concern rather lies in the year-wide compression of war remembrance. Kurihara likens the jagged contours of the media’s commemorative coverage to Japan’s alpine topography. When compared to the small bumps in reflection that emerge each March (the anniversary of the March 10 firebombing) or June (Okinawa Memorial Day), August “towers alone, like Mt. Fuji.”[8]

Critics charge that this seasonal saturation has, in turn, routinized remembrance. Decades of this commemorative cycle, they suggest, have nurtured a rehearsed reproduction of an anti-war stance that often sidesteps more difficult discussions of war responsibility and redress. The results are rituals of memory and expressions of remorse that can appear almost rote. Politicians and pundits issue stale statements about the horrors of war engraved in our hearts, then move on.[9]

To some media watchers, August journalism has cultivated less a spirit of solemnity than a sense of seasonality. Alongside Bon Odori dance festivals, the blast of summer heat, and the Koshien highschool baseball tournament, war reflection is just another beat in the rhythm of the summer calendar. Commemoration bleeds into nostalgia. Themes such as “peace,” “nuclear non-proliferation,” and “anti-militarism” have taken on the feel of seasonal words one might find in a haiku.[10]

The problem is, the threat of nuclear weapons isn’t seasonal, nor are the geopolitical frictions that arise from Japan’s own interpretation of its wartime past. Calendar journalism, in effect, has confined discussion of the war to the first two weeks of August, boxing in debates that, critics argue, should know no seasons. (A similar line of critique has recently emerged regarding “March journalism”: the media’s inclination to peg discussions of disaster preparedness to the anniversary of the 3.11 disaster at the expense of year-round coverage.[11])

If August journalism serves to circumscribe commemoration, it also perpetuates a particular way of remembering. Kurihara is a keen student of what he calls its “grammar”—calcified modes of war reporting, handed down from senior editors to junior reporters, internalized by generations of journalists. A signature feature of this grammar is the use of well-worn phrases about the “regrettable horrors of the past.” The use of the passive voice is another. It’s guided, according to Kurihara, by a simple and inoffensive formula. Open with a profile of the war experience of an air raid survivor or child evacuee or bereaved family member. Note the relevant commemorative proceedings that August. And conclude by proclaiming some version of the stockphrase, “the horrors of war must never again be witnessed.”[12]

There is of course immense value in profiles of this sort. It is, after all, growing only more difficult to find and interview individuals with direct experiences of the war, and reporters should be lauded for their efforts to convey their stories.

Only seldom, however, do these conventions of war memory reporting leave room for evaluating a critical question: who should be held responsible for these “horrors”? Atrocities unfold, bombs blast, and children starve, all without any assessment of the chain of authority or coercive policies that created these circumstances to begin with.

The details of these stories are different, but the takeaway is the same: war is wretched and must be avoided at all costs. Everyone is responsible and thus no one is responsible. Matsuura Sōzō, among the first postwar journalists to train a critical eye on the media’s complicity in the war, feared exactly this outcome in 1971 when he observed that “August 15, which used to be a day for anti-war and peace, is being replaced by a day of national repentance for all.”[13]

Self-Reflections

If August journalism functions as a mirror of postwar society, reflecting the self-images Japan wants to project to the world, what sorts of stories have its authors enshrined?[14]

That question lies at the heart of Yonekura Ritsu’s 2021 book, August Journalism and Postwar Japan. Analyzing not only print media, but also radio, television, and documentary film, Yonekura charts how different eras of August commemoration reflected different preoccupations. At the risk of oversimplification: Where the 1950s were defined by a post-Occupation censorship reckoning with the atomic bombs, the 1960s were animated by Cold War conflicts, and the 1970s by fears of the withering of memory. The messaging on nuclear non-proliferation so central to coverage in the 1980s gave way to a turn toward Asia in the 1990s.[15]

A former producer at NHK, Yonekura understands better than most the vital importance of Japan’s protean postwar media landscape. Each of the commemorative turns outlined above cannot be understood without accounting for changes in the use and penetration of new media technologies. The increasing affordability of television sets in the 1960s, for example, ushered in a pronounced shift in August programming from radio to television, fundamentally altering the visuality of remembrance.[16]

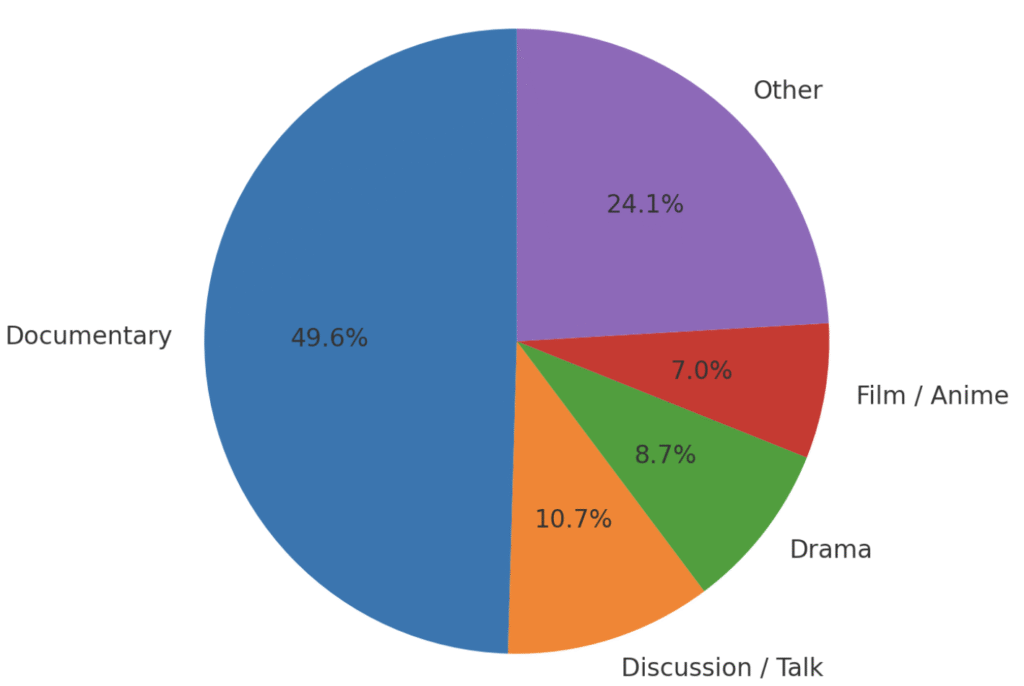

Yonekura marshals an impressive data set in support of his claims. 1965, according to his data, saw the highwater mark in postwar remembrance, with outlets airing 66 distinct segments—a whopping 2,940 minutes of programming—related to August remembrance.[17] Since then, the number has fluctuated between around ten and forty each year, predictably spiking in milestone anniversary years such as this one.[18] Documentaries constitute the preferred genre of delivery, comprising nearly half of the 1,654 postwar television commemorative broadcasts cataloged by Yonekura (see Fig. 1).

For Yonekura, this quantitative analysis is of secondary importance to a qualitative assessment of the meta-narratives of August journalism, the memorial storylines that prevail across the postwar. He pulls out from this coverage three particular narrative threads. One is the story of reconstruction and reinvention. Focusing on the process of “building the postwar,” this narrative marks 1945 as “Year Zero” in the birth of a new Japan. It traces the transformation of Japan into a peace-loving member of the global community and an economic juggernaut, imbuing the postwar period with a particular set of values and sensibilities.[19]

A second narrative concerns the horrors and hazards of nuclear weapons. It centers Japan’s unique position as the only polity in the world to have suffered nuclear holocaust, asserting a special obligation to convey its costs to the world. This commemorative through-line emphasizes Japan’s tragic responsibility to stand on the frontlines of nuclear non-proliferation. Under the banner of “No More Hiroshimas!” it underscores Japan’s enduring commitment to pacifism.[20]

The third narrative type is, according to Yonekura, also the most pervasive: the story of suffering. Each August brings new and harrowing portraits of malnourished child evacuees in the countryside, of abused repatriates, of fires reducing entire neighborhoods to ash and rubble. These accounts are often gut-wrenching and understandably arrest the media’s attention. But they have also served to nurture what Yonekura, citing John Dower, calls a “victim consciousness” in Japan, a fixation on suffering with little heed paid to the question of perpetration at home or abroad.[21]

War damage, in this mode of storytelling, is portrayed as an almost natural disaster. These accounts say nothing of colonial rule and oppression, nothing of the wartime state’s coercion and deceit. August journalism, in this sense, perpetuates the oft-repeated logic, a staple of political stump speeches across the decades, that the “peace and prosperity of the present is rooted in the suffering of generations in the past.”

The Mythos of 8.15

It seems logical, natural even, that August would mark Japan’s season of war remembrance, given the course of Japan’s defeat and its convergence with Obon, Japan’s festival of the dead.

That the surrender announcement read by Emperor Hirohito during his 8.15 “jewel voice broadcast” (gyokuon hōsō) is exactly 815 characters long is taken by some as evidence that this date was fated to be etched into the national psyche.[22]

It would be a mistake, however, to take the memorial magnetism of 8.15 as a given. For the commemorative calendar that today seems routine was not always so. It is rather the product of a host of political and editorial decisions across the postwar period that pressed memorial weight into certain days rather than others. The observance of 8.15 as a day of national remembrance, in other words, is itself a postwar creation, forged by many of the same media forces that animate August journalism into the present.

That process of commemorialization is the abiding concern of Satō Takumi, a true pioneer of August journalism studies. With the skepticism of a media historian and the curiosity of a folklorist, Satō has meticulously scrutinized the facts and fictions surrounding the events of 8.15, which he identifies as the very keystone of postwar memory. Where Yonekura maps the evolution of August storytelling into the present, Satō traces these stories back to their point of origin—the Emperor’s surrender broadcast, an event that was in itself a mass-mediated spectacle.

Satō is hardly the first to question the authenticity of media coverage of the surrender broadcast and the response it elicited. Matsuura Sōzō, for one, has suggested that the Emperor wasn’t the only one to make a “sacred decision” (seidan) that August. The media, he argues, made one as well: the decision to immediately absolve Emperor Hirohito of any war responsibility.[23] But where Matsuura and others have cast their doubts in passing, Satō has put this media production under the microscope. What, exactly, are the Japanese public looking at each August when the media inevitably recycles photographs of crestfallen subjects falling to their knees upon hearing the Emperor’s address? Satō sees in both written and visual coverage traces of the same propaganda the media peddled throughout the war, and unearths considerable evidence of staging and state coordination. 8.15, he shows, involved as much stagecraft as statecraft, raising key questions about the role of the media in rebranding a peace-seeking Emperor at the dawn of the postwar.

Whatever the case, there is broad consensus that this broadcast formed a sort of inception event for August journalism. It stamped August 15—rather than, say, September 2, the date on which the Instrument of Surrender was signed—as the “end of the war.” It likewise fixed 1945—rather than, say, 1952, the end of the Occupation—as the start of the postwar.

For Satō, as Yonekura, 1955 marks another critical watershed. Radio and newspapers invested the first marquee anniversary since regaining sovereignty with special importance. “August 15 is a profoundly significant day,” declared the Asahi Shimbun, “marking both the end of the Pacific War and the beginning of Japan’s postwar journey.”[24] The atomic bombings stood at the crest of this outpouring of coverage. The same issue of Asahi went on to note that the trauma of atomic injury had been visited upon Japan not twice but three times—a reference to the previous year’s Lucky Dragon Boat No. 5 Incident, a major catalyst to Japan’s peace movement.[25] That media outlets would adopt the “Pacific War” label—a viewpoint that subordinates the fighting in Asia to that against the United States—is to Satō a telling indicator of broader shifts in the contours of national memory.

This and other coverage served to consolidate what Satō has called in a recent interview Japan’s “1955 system of memory” (Kioku no gojūgo-nen taisei).[26] The same political forces that gave rise to what political historians have dubbed the “1955 system” of Liberal Democratic Party electoral dominance also breathed life into corresponding norms of remembrance. It served, among other things, to anchor reporting to 8.15, codifying many of the journalistic conventions that are associated with August journalism today.

LDP politics loomed large in the further canonization of 8.15. It was not in fact until May 14, 1963 that 8.15 came to be officially recognized as “End-of-War Day” (Shūsen no hi). This came by decree of the second cabinet of Prime Minister Ikeda Hayato, which issued its Implementation Guidelines for the National Memorial Ceremony for the War Dead. Only then, fully eighteen years after defeat, did it become standard for the country to hold a national memorial service and collectively halt all activities on 8.15 at noon—the same time the Emperor read his broadcast—to collectively pray for peace.[27]

This was followed in 1982 by a decree from the cabinet of Suzuki Zenkō bestowing on 8.15 the now cumbersome official designation it carries today: the “Day to Commemorate War Dead and Pray for Peace” (Senbotsu-sha o tsuitō shi heiwa o kinen suru hi). This, Satō suggests, was tied inextricably to government-led efforts to nationalize the Yasukuni Shrine, providing the LDP cover for normalizing ministerial visits, if not securing state support for the shrine.[28]

Satō has been outspokenly critical of the “inward-looking” nature of the 8.15 proceedings. What could be sorely needed opportunities to foster international dialogue with former colonies and now vital allies, he argues, have instead become rituals for internalizing remorse. The memorial monopoly of 8.15, moreover, has crowded out other milestones of the war. Why not also reflect on July 7 (the anniversary of the 1937 incident sparking the Second Sino-Japanese War) or December 8 (the attack on Pearl Harbor)? Is the end of the war, he asks, more important than its beginning?

Treating 8.l5 as a neat, clean “end” of the war invites other analytical problems as well. The Emperor’s broadcast may have brought hostilities to a halt on the main islands, but it didn’t bring an end to combat against the Soviets in the northern reaches of the Kuriles or the Manchurian frontier. So, too, did the broadcast mean something rather different to Okinawans, who have chosen two alternative dates to commemorate peace and their war dead. The preoccupation with 8.15 effectively obscures these alternative “endings” to the war. It flattens the experience of defeat to that only of subjects and soldiers at the imperial core.[29]

There is a venerable tradition among writers and intellectuals of deliberately bucking this trend—of counter-commemoration. Novelist and pacifist Oda Makoto made a point of holding an anti-war rally every year on August 14. He did this in part to remind his countrymen that when the Emperor made his 8.15 broadcast Kumagaya and other cities firebombed on August 14 were still burning.[30] Literary critic Etō Jun advocated alternatively for paying tribute at 4:00pm on August 16, on account of it being the moment the Imperial General Headquarters issued its ceasefire order. More than the Hirohito’s broadcast, he argued, this was truly consequential in bringing the war to an end.[31]

Satō has recently floated a different alternative. Proposing a turn to “September journalism,” he has suggested enshrining a second day of national reflection: September 2. To Satō, this, the day Japan’s leaders actually signed the Instruments of Surrender aboard the USS Missouri, is a critical and all-too-often overlooked milestone for Japan. It is, after all, the moment the war ended in the letter of international law, a turning point celebrated to this day with speeches and parades in Moscow and Beijing.[32]

More specifically, Satō has proposed a disaggregation of the “Day to Commemorate War Dead and Pray for Peace.” Why not break it into two—a day of mourning and prayer (8.15), followed by a day of discussion and debate (9.2)? Rounding out the commemorative calendar in this way would allow for a fuller reckoning with the uneven costs and consequences of Japan’s imperial expansion and collapse. It could, he suggests, stimulate reflection on the mass murder of Koreans in the wake of the September 1, 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. Or it might spur greater dialogue regarding the Mukden Incident of September 18, 1931, a decisive moment in Japan’s territorial expansion. A national day of remembrance on 9.2 would have the added benefit of taking place after Japan’s schoolchildren are back in the classroom, giving teachers new opportunities for curricular engagement on the war for those who need it most.[33]

The “Unfinished War”?

To these critiques, Kurihara has added another: that August journalism unwittingly relegates the war to a bygone era, one unconnected to the present. For child survivors of air raids, however, the end of the war was only the beginning of their hardship. Whether orphaned or injured, survivors across the 66 cities (and scores of villages) attacked in 1945 now had to endure the physical and psychological ailments they would carry with them for the bulk of their lives. “The brightness I initially felt after the war,” remembered Suzuki Chieko, severely injured by a strafing attack at Ōji Station in Nara Prefecture, “quickly turned into a new kind of war: the struggle of postwar life.”[34]

Suzuki struggled mostly on her own, the bullet fragments lodged in her back a source of debilitating pain. This stood in stark contrast to the military veterans all around her. No sooner did Japan regain its sovereignty under the 1952 San Francisco Peace Treaty than its government resumed relief and welfare programs for military personnel, employees, and their families. While these groups have received over 60 trillion yen in financial support since 1952, Tokyo’s civilian bomb survivors have received no relief of any kind.[35]

This is not for want of trying. Riding a surge of “war memory activism,” these survivors have since the late 1970s pursued every avenue available to receive some form of relief for their injuries as well as state support for an array of memorial projects.[36] They filed litigation against their own government, arguing essentially that since the wartime state started the war they should be held accountable for the damage it caused.[37]

When Japan’s Supreme Court denied them relief, arguing that only legislation could remedy their claims, they took their fight to the Diet. Fourteen times between 1973 and 1988, survivor groups submitted a petition for some form of token compensation. And fourteen times they were shot down by lawmakers in the Liberal Democratic Party. The LDP’s opposition rested on what has come to be known as “war damage endurance doctrine” (sensō higai juninron): the idea that because all citizens suffered damage in some way during the war, they should all endure its consequences equally.[38]

Tokyo’s air raid survivors, in effect, became a political football, passed around by each branch of their own government. The state refuses relief on the grounds that civilians were not government employees during the war. The court recognizes harm, but shirks responsibility, passing the buck to the legislature. The Diet, meanwhile, does nothing. Kawai Setsuko, a leading figure in this memorial movement, captured the sentiment of many fellow survivors when she observed that “the state is just waiting for us to die.”[39]

Tokyo’s memory activists have regrouped and adapted, pouring their energies into projects of grassroots memorialization of all sorts. They’ve built and maintained local monuments in neighborhoods wiped clean of all material reminders of the war. They’ve painstakingly compiled oral histories, archival materials, and lists of the dead. After the Tokyo Metropolitan government reneged on a financial pledge of support for a memorial museum, they raised funds and built it themselves.[40]

Their activism, like their wartime injury, is perpetual. It is a relentless, ongoing affair. And now that many of these survivors are passing away, it is slowly creeping to a halt.

This, to Kurihara, is precisely what is obscured by August journalism: the deep connection between past and present, the still open wounds of those who experienced the war. Canned reporting on the end of World War II runs the risk of rendering its battles into epic tales of a distant world. In his own writing, Kurihara now tries to avoid using the phrase “X years since the end of the war,” recognizing that for many survivors the conflict hasn’t ended. He proposes as an alternative mikan no sensō, “the unfinished war.”[41]

Three Lessons

It’s easy to critique August journalism from afar, to lament the monotony of reporting or demand more complex representation. Kurihara, for his part, doesn’t share in the singularly derisive view of some critics. Years of shoe-leather reporting have left him deeply sympathetic to the challenges faced by journalists—generalists by profession—suddenly assigned to the war memory beat. He applauds those who do their best under trying circumstances. Kurihara himself wears the label of “August journalist” as a badge of honor, vowing to conduct “August journalism all year round.”[42]

That task is growing more difficult in Japan with each passing year. The voices of those with firsthand memories of the war are fading. This year’s 80th anniversary may well represent one of the last major moments when those who actually carried out frontline combat are around to share their stories. While Kurihara could, for instance, once easily track down multiple former members of the Tokkō, he now struggles to find a single veteran to speak on these kamikaze attack units.[43] Moving forward, the task of bearing witness will fall increasingly on the children of the war, those with limited memories and particular vantage points. This demographic shift will undoubtedly shape which stories of the war get told and which do not.

Some journalists have responded to this shift by reorienting coverage toward the “passing of the baton”—profiling not just kataribe (survivor-storytellers), but kataritsugibe (passers-down) as well. Kurihara has decided to refrain from this vein of reporting for now, prioritizing instead the hunt for the stories of survivors who have not yet spoken.[44]

The sheer volume and changing delivery of news present further challenges. In our hyper-connected age of TikTok, X, and Youtube, public interest in traditional media is waning. How can journalists capture the attention of readers with yet another story on the legacies of World War II when they are competing with a torrent of social media clips of wars in the present built for viral content propagation?

Kurihara sees far more than historical awareness at stake in these questions. His media criticism is also animated by a firm conviction that journalists should stand as a bulwark against the lurch toward war—precisely what his predecessors failed to do in the late 1930s. Kurihara understands all too well the wartime collaboration of journalists, including those at his own newspaper, in perpetuating militarism and propaganda.[45]

Drawing on these experiences, Kurihara sets forth in his new book three particular responsibilities that rest on the shoulders of journalists today.

- “Expose the deceptions of governments driving toward war, along with their unachievable schemes and fantastical policies.”[46] When confronted with lies and delusions, Japan’s own journalists cowered. Those today must expose fictions and fabrications for what they are.

- “Convey how extensive the damage would be if a new war were to occur.”[47] Japan’s officials severely underestimated the toll that the war would bring to their own cities and civilian inhabitants. Compliant journalists let them off the hook. Journalists today must force the disclosure of damage assessments and foster debate on these estimates.

- “Make visible the damage of past wars.”[48] In times of crisis and conflict media attention can ricochet from one topic to the next, making it difficult to assess the risks at hand. Journalists have a particular obligation to provide a check against the inexorable swirl of contemporary events to put matters of war in historical perspective.

Kurihara calls, in the most basic sense, for specificity. To deter war, journalists need to quickly dispense with abstractions and the comfort of stock phrases. Rather than simply declare “we deplore war and stand against it,” he suggests, reporters need to graphically communicate its toll.

Global August

Scholars of August journalism are adamant that its practice is unique to Japan, and for good reason. Many of its defining features are indeed rooted in Japan’s particular experiences of the atomic bombings, unique media landscape, and distinctive postwar politics.

And yet, if global media coverage of this year’s 80th anniversary proceedings are any indication, Japan is hardly the only country to fixate on the memorial significance of a few days in August. A case can be made that Americans partake in their own form of August journalism. Like clockwork, August brings in the United States the same rehashing of now decades-old debates on the morality of the atomic bombings. Experts come out of the woodworks to expound on the potential costs of a land invasion, deliberations of Japan’s high command, and the Emperor’s role in surrender. New books, editorials, podcast episodes, Reddit forums, and films parse the twists and turns of a few pivotal days in August to answer some version of the same question: were the atomic bombings necessary? These debates, while necessary, sometimes devolve into their own sort of hollowed-out ritual.

The events of 2025, however, raise questions about the history and memory of World War II that demand something more. They require a fuller consideration of how the leveling of Japan’s cities in 1945 is being used to explain, if not justify, the wholesale destruction of Gaza.[49] They call for greater contemplation of the afterlives of the bombing campaigns underway in Gaza and Ukraine, the legacies of air raids that will long weigh on those fortunate enough to survive them. If, as Kurihara suggests, it’s the responsibility of journalists to reveal the costs of some future war, they might start by clarifying what the changing face of drone-driven air power on display in these war zones might look like closer to home.

Our present moment requires, not least, a clear-eyed assessment of active efforts by the Trump administration to constrain historical inquiry and censor the historical record. The meaning of “the Enola Gay Controversy” has taken on new meaning in 2025, a year that saw photographs of the plane that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima flagged for removal from a Department of Defense database, ostensibly because they had the word “gay” in their meta-data.[50] Media outlets that lavish attention on this year’s 80th anniversary would do well to also track the ongoing assault on the archive, the very foundation of historical research.

This year’s 80th anniversary occasioned in Japan many of the familiar August rituals described above. Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru certainly kept tradition alive this past 8.15 when he stated that “We will not forget, even for a moment, that the peace and prosperity that Japan enjoys today was built atop the precious lives and the history of suffering of the war dead.”[51]

Yet some of those watching closely detected something new. “What felt a little different from previous years,” noted filmmaker Sōda Kazuhiro in a debrief on the August proceedings, “was the increasing number of voices suggesting that we are now in a new ‘prewar’ period rather than a ‘postwar’ one.”[52]

What this means for Japan, for the US-Japan relationship, and for World War II memory writ large are questions of urgent importance for us all.

Notes:

[1] On the origins of this column, see Kurihara Toshio, Tokyo daikūshū no sengoshi (Tokyo: Iwanami shinsho, 2022), 210.

[2] Of the 122 stories filed for the column between July 25, 2019 and December 2, 2021, roughly half are dedicated to the history and memory of the Tokyo air raids, with the other half focusing principally on the search for and repatriation of the remains of Japan’s war dead overseas. Each installment of the column can be accessed here: https://mainichi.jp/ch190742116i/%E5%B8%B8%E5%A4%8F%E9%80%9A%E4%BF%A1

[3] Kurihara, Tokyo daikūshū no sengoshi, 210.

[4] He later spun off this reporting into a book on the topic, Kurihara Toshio, Tokyo daikūshū no sengoshi (Tokyo: Iwanami shinsho, 2022).

[5] Released in August 20205 to coincide with the 80th anniversary, this book is Kurihara Toshio, Sensō to hōdō: “Hachigatsu jānarizumu” wa owaranai (Tokyo: Iwanami Bukkuretto, 2025).

[6] His landmark study on this topic is Satō Takumi, Hachigatsu jūgonichi no shinwa: shūsen kinenbi no media-gaku (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 2005).

[7] See, for example, Yonekura Ritsu, “Hachigatsu jānarizumu” to sengo Nihon: Sensō no kioku wa dō tsukurarete kita no ka (Tokyo: Kadensha, 2021); and Yonekura Ritsu, “Terebi ni okeru ‘hachigatsu jānarizumu’ no rekishiteki tenkai: dokyumentarī bangumi no hensei no hensen o chūshin ni,” Seikei kenkyū Vol 54, no. 3 (2017): 329–370.

[8] “Mainichi Shimbun × Yomiuri Shimbun ‘Sensō Kisha’ taidan: Hachigatsu jānarizumu to sengo 80-nen. Shuzai shiteiru no wa ‘Owatta sensō’ de wa naku ‘Mikan no Sensō,’” Foresight, August 9, 2025. Accessed online August 22, 2025: https://www.fsight.jp/articles/-/51531

[9] For a brief historiographical overview of this line of critique, see Yonekura, “Hachigatsu jānarizumu” to sengo Nihon, 7-11.

[10] In a clever analysis of seasonal haiku dictionaries, Satō Takumi has shown this to be quite literally true: “Shūsen-hi” (End-of-War Day) and “Gyokuon” (Imperial Rescript Broadcast) are, among other related terms, gathered in these dictionaries under the label of autumnal words, alongside Urabon-e (the Bon Festival of the Dead). See Satō, Hachigatsu jūgonichi no shinwa, 129-130.

[11] This critique is elaborated in Yamaguchi Hitoshi, “Karendā jānarisumu hihan no kōchikusei ni kansuru sho mondai: ‘Hachigatsu jānarisumu’ ron kara ‘Sangatsu jānarizumu’ o kentō suru,” Jānarizumu & Media: Shinbun-gaku Kenkyūjo Kiyō Vol. 19 (2022): 7-21.

[12] On the “grammar” of August journalism, see Kurihara, Sensō to hōdō, chapter 3, e-book version.

[13] “Ano higeki o kesu na — taiken koso saidai no buki,” Yomiuri Shimbun, August 15, 1971.

[14] “Hachigatsu jānarizumu ga utsusu Nihon no jigazō: “naze” keishō suru no ka jimon o,” Asahi shimbun, August 26, 2023. Accessed online, August 18, 2025: https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASR8N63MMR8BUPQJ00S.html

[15] Each decade essentially comprises a chapter of the book. See Yonekura, “Hachigatsu jānarizumu” to sengo Nihon, chapters 1-5.

[16] As discussed in Yonekura, “Hachigatsu jānarizumu” to sengo Nihon, chapter 2.

[17] Yonekura, “Hachigatsu jānarizumu” to sengo Nihon, 78-79.

[18] Yonekura, “Hachigatsu jānarizumu” to sengo Nihon, 23.

[19] As discussed in Yonekura, “Hachigatsu jānarizumu” to sengo Nihon, 38.

[20] As discussed in Yonekura, “Hachigatsu jānarizumu” to sengo Nihon, 52-65.

[21] Yonekura, “Hachigatsu jānarizumu” to sengo Nihon, 262.

[22] This numeral coincidence is examined in Satō, Hachigatsu jūgonichi no shinwa, Introduction.

[23] Matsuura Sōzō, Tennō Hirohito to chihō toshi kūshū (Tokyo: Otsuki shoten, 1995), 195.

[24] As quoted in Satō, Hachigatsu jūgonichi no shinwa, 113.

[25] As quoted in Satō, Hachigatsu jūgonichi no shinwa, 116.

[26] For a brief discussion of this 1955 memory system, see “Tokushū: Shōwa hyaku-nen kara tou” Gendai Shisō No. 08 (August 2025): 12.

[27] Satō, Hachigatsu jūgonichi no shinwa, 75.

[28] For a discussion of these deliberations and political calculations see, Satō, Hachigatsu jūgonichi no shinwa, 120-125.

[29] For thoughts on the multiple endings of World War II in Japan, see “Takumi Sato: Japan should stop acting like World War II ended on Aug. 15,” Asahi shimbun, September 1, 2024. Accessed online August 23, 2025: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15389640

[30] As discussed in Matsuura Sōzō, Tennō Hirohito to chihō toshi kūshū (Tokyo: Otsuki shoten, 1995), 185.

[31] As examined in Satō, Hachigatsu jūgonichi no shinwa, 84.

[32] “Sengo 80-nen rekishi ninshiki no henkaku o, Satō Takumi,” Intelligence Nippon, July 10, 2025. Accessed online August 20, 2025: https://www.intelligence-nippon.jp/2025/07/10/5582/.

[33] “Hachigatsu jūgo-nichi ni owatta sensō nado nai: Heiwa hōdō wa kugatsu ni shifuto o,” Asahi shimbun, July 26, 2024.

[34] As quoted in NHK, eds., NHK Supesharu, Sensō no shinjitsu shirīzu 1: Hondo kūshū zenkiroku (Tokyo: KADOKAWA, 2018), 143.

[35] For a discussion of this postwar relief, see Kurihara, Sensō to hōdō, chapter 3, e-book version.

[36] These projects include the construction of an official air raid memorial (distinct from the Yokoamichō Park memorial site) and state support for compiling an official list of those killed in the air raids. The pursuit of both goals is explored in Paper City (2021), a documentary film focusing on memory activism of Tokyo’s air raid survivors.

[37] On this legal fight, see, for example, Cary Karacas, “Fire Bombings and Forgotten Civilians: The Lawsuit Seeking Compensation for Victims of the Tokyo Air Raids,” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol 9, Issue 3 No 6, January 17, 2011.

[38] On the legal rationale underpinning this theory, see Kurihara, Tokyo daikūshū no sengoshi, chapter four.

[39] As quoted in Kurihara, Tokyo daikūshū no sengoshi, 181.

[40] For an English-language overview of these projects of grassroots memorialization, see Cary Karacas, “Place, Public Memory, and the Tokyo Air Raids,” Geographical Review Vol. 100 (2010): 521-537.

[41] Kurihara, Sensō to hōdō, Introduction, e-book version.

[42] Kurihara, Sensō to hōdō, chapter 4,e-book version.

[43] Kurihara, Sensō to hōdō, chapter 4, e-book version.

[44] Kurihara, Sensō to hōdō, chapter 4, e-book version.

[45] For a landmark study of wartime newsprint journalism and its support of the war, see Suzuki Kenji, Sensō to shimbun (Tokyo: Mainichi Shimbunsha, 1995).

[46] Kurihara, Sensō to hōdō, chapter 4, e-book version.

[47] Kurihara, Sensō to hōdō, chapter 4, e-book version.

[48] Kurihara, Sensō to hōdō, chapter 4, e-book version.

[49] Examples of these comparisons are too numerous to compile here. See, for example, “Israel ambassador says Gaza, post World War II comparison ‘baseless,’” Kyodo News, October 13, 2024; and “Lindsey Graham sees Israel taking Gaza by force to wrap up war,” Politico, July 27, 2025.

[50] On the “Enola Gay controversy” of 2025, see “The Pentagon’s DEI Panic,” The Atlantic, March 7, 2025.

[51] Prime Minister’s Office of Japan, “Address by Prime Minister Ishiba at the Eightieth National Memorial Ceremony for the War Dead,” August 15, 2025. Accessed online August 28, 2025: https://japan.kantei.go.jp/103/statement/202508/15shikiji.html

[52] “Hachigatsu jānarizumu ni kaketa giron,” Magajin 9, August 20, 2025. Accessed online, August 22, 2025: https://maga9.jp/250820-2/