[Ed. Note: This article is part of a collection of essays entitled “Critical Reflections on the 80th Anniversary of the End of World War II” published in August 2025.]

Keywords: war commemoration, war memories, World War II, contested memories, victim consciousness

This year, the world is commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of WWII. One thing that has not changed over the past eight decades is how the forms and focus of commemoration vary considerably across countries. The United States, for example, commemorates the war differently in relation to the Asia-Pacific and European theaters, reflecting differences in military experiences, post-war impact, and historical memories. The European victory is remembered as a clear military and moral triumph, with the defeat of Hitler and Nazism. D-Day – the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944 – is celebrated as a key event. In contrast, the Pacific victory is more complicated, involving controversies over the use of atomic bombs, the Tokyo Tribunal as “victor’s justice,” and the racial dynamics of the U.S.-Japan conflict, including the internment of Japanese Americans. Commemorations largely focus on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. victory over Japan.

Within Asia, war memories and commemorations are not only different from those in the U.S. but also divided and contested. Japan’s remembrance is marked by narratives of victimhood and pacifism, while neighbor countries like China and Korea stress Japanese wartime atrocities. Accordingly, there is no single date or event that Asians commemorate together. Furthermore, divergent memories of war have been a source of tension in their bilateral relationships, and China’s narrative of the Asia-Pacific war, which emphasizes national resistance and victory over a foreign power, is increasingly invoked to stoke anti-foreign nationalism against the U.S.

Divergent Memories and Commemorations

The divided nature of historical memories in the Asia-Pacific region stems from the imbalance or difference in focus in the formation of war memories in these countries.1

For the Chinese and Koreans, Japanese acts of aggression, like the Nanjing massacre, forced labor, and sexual slavery, are the most crucial in their remembrance of the war. On the other hand, actions involving the U.S., such as the attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. bombings of Japanese cities (both atomic and firebombing), carry the most weight in shaping Japanese war memories. China and Korea are not as significant to Japanese war memories as is the U.S. Likewise, Japan is a central player in Americans’ memory of the Pacific war, whereas China and Korea are not as prominent.

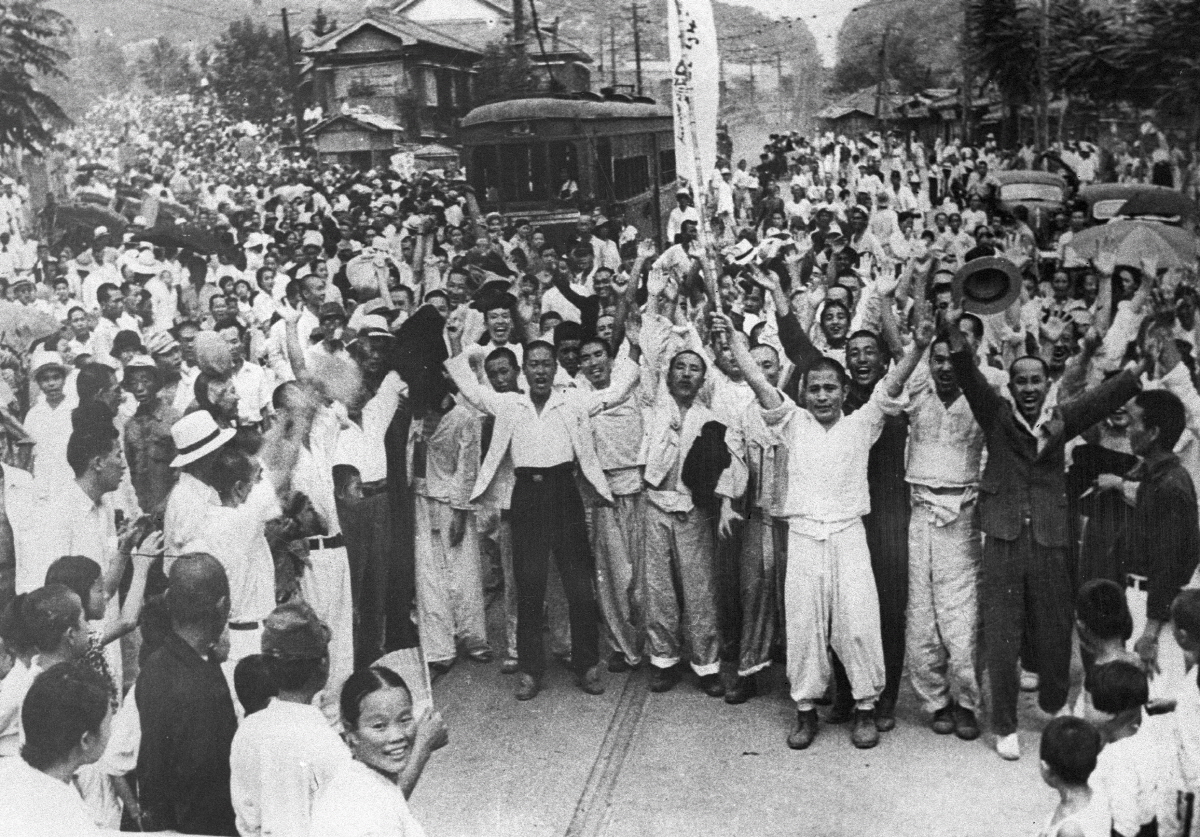

Such divergent memories naturally lead to different commemorations of the war. Chinese celebrate their victory over Japan in the Pacific War on September 3, while Koreans celebrate the nation’s “Day of Liberation” from Japanese rule on August 15. For Japan, however, there is no single national day of commemoration, reflecting its ambivalence about the war. Memorial services honoring the victims of the bombing are held in Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, respectively, and on August 15, known as the “End of War Memorial Day,” Japanese leaders visit Yasukuni Shrine where war criminals are enshrined. Meanwhile, the U.S. officially “remembers” only the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor, with an annual memorial parade and commemoration held on December 7, though there is growing critical reflection on the Manhattan Project in recent years. U.S. presidents have attended D-Day anniversaries with European leaders, but no such collective commemoration occurs with Asian counterparts. The war ended a long time ago, but the fractured nature of its legacy continues today.

Contemporary Politics

The historical memories of the war also affect contemporary politics in the Asia-Pacific region, especially Japan’s relations with its neighbor countries and recent U.S.-China tensions. Japanese historical memory’s focus on the U.S. both reflects and explains Japan’s postwar victim identity and reluctance to fully engage Asian neighbors regarding its colonial aggression and wartime atrocities. Unlike Germany, postwar Japan witnessed the development of a mythology of victimhood, in which many innocent civilians were sacrificed because of the massive and destructive U.S. bombings of cities as well as the military (gunbu), portrayed as a force that went out of control. Victim consciousness provided fertile soil for the emergence of postwar neo-nationalism that denied Japan’s responsibility for wartime atrocities, hindering reconciliation with China and Korea. It has, in turn, fueled the rise of anti-Japanese sentiments in both countries during much of the postwar period until now.

More recently, China has been promoting a form of anti-foreign nationalism based on historical memories of the war. Framing it as “the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, 1937–1945,” China presents itself as the victim of imperialist aggression but also the victor that emerged through suffering. The Chinese Communist Party uses WWII commemorations to legitimize its rule, portraying itself as the true defender of the Chinese nation against imperialism. This narrative feeds China’s “never again be humiliated” mindset, which underpins its pushback against U.S. dominance in Asia, though China and the U.S. were not adversaries during WWII. As China increasingly emphasizes the CCP’s leadership in the anti-imperialist and anti-fascist struggle, this renewed focus in its historical narrative will serve as a valuable political resource in its escalating competition with the U.S.

Commemorating Together?

On the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII in 2015, I urged Asia-Pacific leaders to recognize a simple truth: “only when they are able to celebrate shared memories of war and colonialism can the region, now ridden with conflict, become more peaceful and prosperous.”2 That call is not only still relevant today but more urgent than ever. In an era dominated by strongmen who weaponize nationalism and manipulate historical memory for political gain, the distortion of the past has become a common tool of division and confrontation. It is imperative that U.S. and Asian leaders, rather than continuing to commemorate their fractured memories, can come together to mark the end of the Asia-Pacific war jointly, as has been done in Europe. Only then can they present a credible, collective vision for the peace and prosperity of this important region grounded in the hard-earned lessons from the unfortunate past.

- See Gi-Wook Shin and Daniel Sneider, Divergent Memories: National Opinion Leaders and the Asia-Pacific War (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016).

- Gi-Wook Shin, “Colonialism, Invasion, and Atomic Bombs: Asia’s Divergent Histories,”The Diplomat (August 12, 2015). https://thediplomat.com/2015/08/colonialism-invasion-and-atomic-bombs-asias-divergent-histories/.