[Ed. Note: This article is part of an ongoing series and online exclusive exploring contemporary artists through interviews, commentary, and visual engagements provided by art historian Asato Ikeda. For other interviews in this series, see “Art and Politics with Asato Ikeda.“]

Abstract: This article features a conversation with contemporary Japanese artist Toshie Takeuchi, whose work integrates historical research, participatory art, and collective practices to explore themes of memory, trauma, colonialism, and relationality. From her performances on Palestine to her exploration of wartime memory in Japan and uranium mining in Congo, Takeuchi’s projects examine erased histories and the intersections of imperialism and exploitation. Highlighting her journey from Japan to the occupied Congolese Embassy in The Hague, the discussion emphasizes her commitment to collaborative art-making as a decolonial practice and a critique of individualism, fostering relational connections through collective creativity.

Keywords: Japan, Denmark, Palestine, Congo, War

Toshie Takeuchi is a visual artist, filmmaker, and organizer of community art activities. Her work is often based on careful historical research and community workshops.1 Born in Aichi, Japan, and having completed her BA in photography at London College of Communication in the University of Arts London and MFA at Aalto University in Helsinki, she currently lives and works in Copenhagen, Denmark. Her works have been internationally exhibited as part of solo/group shows in Denmark, the Netherlands, Canada, Belgium, Finland, Russia, Hong Kong, and Japan. Most recently, she was invited to the 2024 Lubumbashi Biennale in the Democratic Republic of Congo to present her work on the history of uranium and nuclear bombs/energies in Shinkolobwe and Hiroshima/Nagasaki.

Ikeda: It is fitting to have this conversation on December 9, as I realized I attended your participatory performance on Gaza on the exact same day last year. We befriended over pro-Palestinian demonstrations in Copenhagen where we met and I happened to live at that time. The information about the demonstrations was initially only available in Danish, and I contacted you to ask you where and when the next one would take place. In Copenhagen, so many people have been protesting since October 2023, literally filling the streets. Perhaps we could start our conversation by talking about your work on Palestine, then move on to discuss your work about Japan during the Second World War and Congo. Would you mind explaining what you did on December 9 last year?

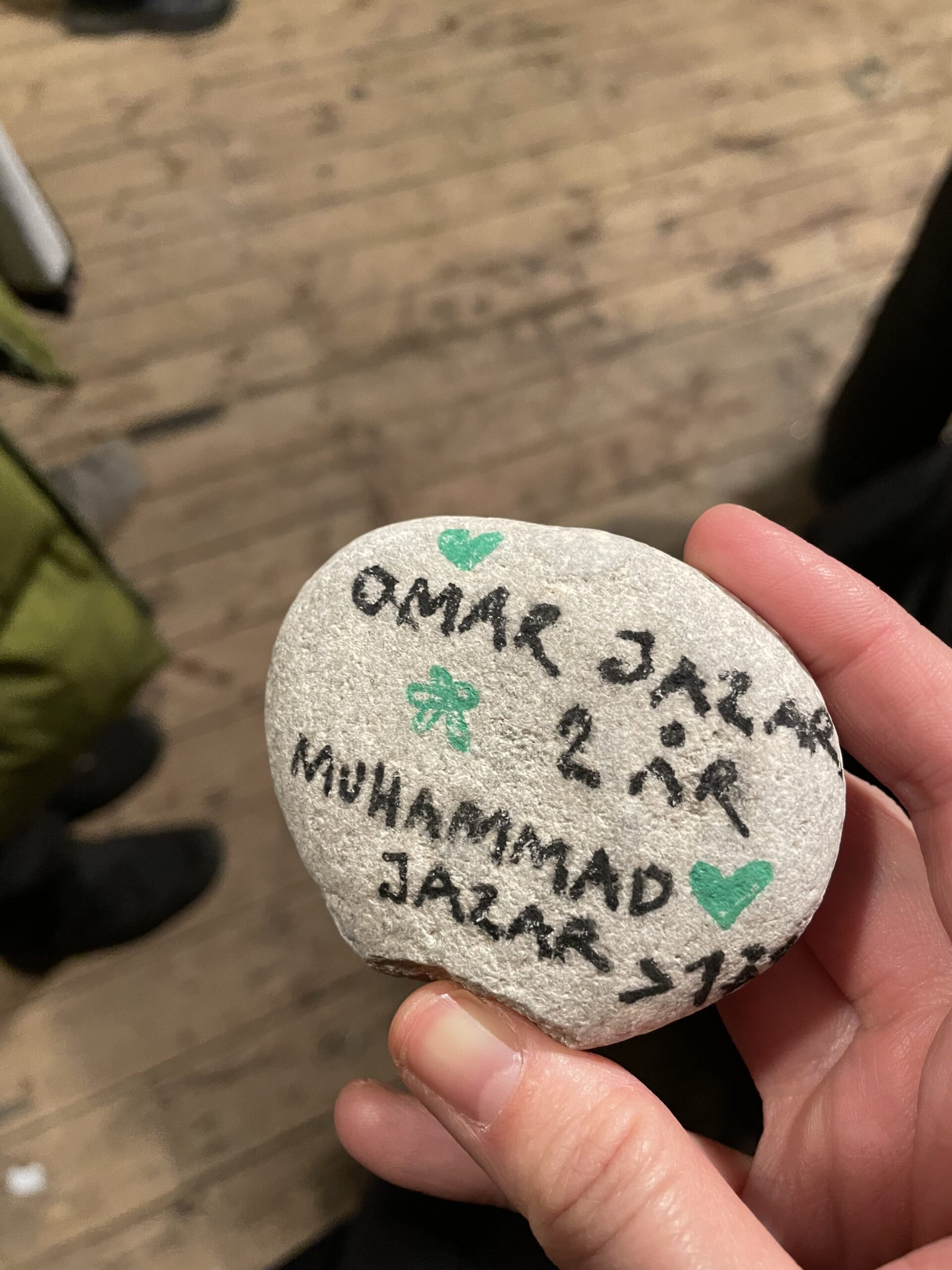

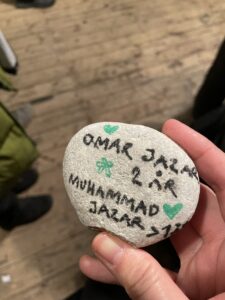

Takeuchi: I performed my work How to Reconnect, which I had been performing for a while in different contexts, at the fundraising event for Gaza and Palestine at Astrid Noacks Atelier on Rådmandsgade. For that event, I borrowed pebbles from Blågårds Plads, where activists had held an event to memorialize the victims in Gaza by writing out their individual names and ages and reading them aloud. I was very touched by their activity and wanted to connect the two events. In my performance, I instructed the participants to hold the pebbles using their bodies. We started with groups of two people holding the pebbles together, then groups of three and four, and in the end, all of us—about forty people—held small pebbles between each other, between our shoulders, knees, and cheeks (Figure 1, 2). It was my very first work on Palestine.

Figures 1, 2. Toshie Takeuchi, How to Reconnect at the fundraising event at Astrid Noacks Atelier on Rådmandsgade, Copenhagen. December 9, 2023.

Ikeda: I remember it being a very intimate event, with everyone being physically close to one another. It was contemplative, and your work, along with the entire event, brought together the community of people concerned about what was happening in Gaza through art.

You later invited me to make kites for pro-Palestine demonstrations, in which I participated in late December. With others who participated in your kite-making workshops, we then marched with the kites together during one of the demonstrations in March 2024. Would you like to tell us a bit about that work?

Takeuchi: I had been working with kites for some time, including a project I call Play it on the Sky—Borderless Praxis with Kites, where kites are used collectively to interpret a landscape and transform it in the sky as a projection of hope. This kite project for Palestine also emphasized collectivity. I created it with my friends in the Black feminist practitioners’ collective Dreamship, organized by Susan Zekiros. It was our response to the Palestinian poet Refaat Alareer (1979–2023) and his poem If I Must Die.2 Alareer was killed in December 2023 by Israeli bombings, and I felt the kite project as a form of community-building would resonate profoundly. We wanted to ensure the kites were not made individually but as a collective effort. We discussed making multiple kites and flying them as a collective and see what kind of landscape or scenery we can create in the sky together (Figure 3). We held multiple workshops to create the work, we started the workshop by reading Alareer’s poem and discussed what we wanted to depict on the kites. The collective of seven kites features symbols such as Handala, a cartoon figure that has come to represent Palestinian resistance, a key symbolizing the right to return, and an olive tree. We marched with the kites on March 30 to mark Palestine’s Land Day and later flew them at Amager Strandpark in June (Figure 4, 5, 6, 7).

Figure 3. Kites-making workshop, Copenhagen. December 2023.

Figures 4, 5. Kites made by Toshie Takeuchi and the collective Dreamship, Demonstration and Art Parade for Palestine, Copenhagen. March 30, 2024.

Video 1. Demonstration and Art Parade for Palestine, Copenhagen. March 30, 2024.

Figures 6, 7. The collective Dreamship flying kites. Copenhagen, June 2024.

Asato: Would you explain what a kite means to you? We will talk about this more in a moment, but your work about your father, Refuturing the Soil-1, also uses kites.

Takeuchi: I grew up flying kites as part of community activities in Aichi, I enjoyed the communal and transformative aspect of flying kites. I have been exploring how the kite can serve as a tool for empowerment.

Ikeda: This might be a good moment to talk about your work Refuturing the Soil-1 From the Lost Memory of Hikoshichi, which is about your father and his experience of losing his own father—your grandfather—during the Second World War.

Takeuchi: When I was having repeated troubles with a friend, I spoke to a therapist in Denmark. That’s how I learned that my childhood wounds, which I kind of forgot about, have affected me in my relationships as an adult. This made me wonder if my father, with whom I’ve had a very difficult relationship, also had experienced childhood trauma that affected him psychologically. Until that time, I didn’t reflect on the Asia-Pacific War from my own family’s or from the local city’s perspective. My father survived the air raid in Handa City, Aichi Prefecture, which killed hundreds, including his father, Hikoshichi, when my father was just eight years old. However, in my family and my father’s family, we rarely talked about the war or acknowledged my grandfather’s death. As a child, I was simply told that he was hit by a bomb and died. I must admit that I accepted this explanation, as if it were an ordinary and unremarkable way to die. My grandfather wasn’t drafted into the military due to his disabled leg, and I believe this led my father’s family to subconsciously diminish him and the circumstances surrounding his death.

In Japan, we often take war experiences for granted because they were so widespread. I believe that the memories of air-raids in local cities have often been diminished. What we know about the war is often shaped by larger, external narratives. I hadn’t fully considered how deeply my closest family members and my familiar local city could have been traumatized. Even though Japan was a perpetrator during this war, I wanted to explore how ordinary citizens, like my father as a child, experienced and could have been traumatized by the violence and how that affected the contemporary family format of Japanese society.

I researched how to talk to people with trauma and I used this artmaking as an opportunity to have a conversation with my father, who had never discussed his wartime experiences, as a form of therapy. We had four or five sessions, and for the first time, my father cried in front of me.

Ikeda: For your Refuturing the Soil-1, which you showed as work in progress at Eks-Rummet Copenhagen in 2023, you created a sculptural work of two hands holding a kite, eight kites as a group, and a 45-minute video. Would you explain the design of the kites and what the video contained (Figure 8 and 9)?

Takeuchi: I created the drawing based on the most common shape of Japanese kites, inspired by interviews with my father and local victims who were of a similar age to him. It also draws from published testimonies by the Society to Remember the War and Air Raid in Handa (Sensō to Kūshū wo Kirokusuru Kai). Members of the Society have been documenting local testimonies for more than thirty years, starting in the 1980s. While most testimonies were collected in the early years, even a few years ago, new accounts emerged from survivors of the air raid.

The central image on the kites depicts my father as a child being carried on his father’s shoulders, as this is the only memory he has of his father interacting with him. Japanese imperialism is symbolized by the image of a Shinto shrine gate. After the air raid, my father ran into a nearby shrine but was scolded and blamed by adults for entering. According to Shinto myth, because a family member had died, his body was considered unclean, making it taboo to enter the shrine. From another testimony, I learned that while the shrine gate survived the raid, the rest of the shrine was completely destroyed. The combination of these stories reminded me of the deep sickness in Japanese society—the monarchy was preserved, and fascism, at its core, never truly died.

The video was presented as a work in progress and includes interviews with my father and a historian from the Society. Handa was targeted because it housed the Nakajima Aircraft Company, the largest airplane manufacturer in the region. In the final year of the war, the company mobilized thousands of youth laborers, some as young as fourteen years old, from across Japan, as well as forced laborers from Korea. The Society honors these laborers by recovering their original names, including the Korean names that had been replaced with Japanese ones during their registration.

Ikeda: Where does this idea of “refuturing,” which you include in the work’s title, come from?

Takeuchi: It comes from Rolando Vázquez’s use of the term “defuturing,” which describes how modernity creates erasure, rapture, and disconnection. His concept is closely tied to discussions of decoloniality. I think there were two instances of “defuturing” in Japan’s modern history: the transition to the Meiji era and the postwar period. After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, what existed before was erased. Everything became “flat” and the relationality between things were destroyed.

Figures 8, 9. Toshie Takeuchi, Refuturing the Soil-1 from the Lost Memory of Hikoshich. EksRummet, Copenhagen, 2023.

Ikeda: Now that you mention Hiroshima and Nagasaki, perhaps this is the perfect time to move on to our conversation about your work in Congo. You were invited to present your work at the 2024 Lubumbashi Biennale, and that work was about the mining of uranium in Congo and the making of the atomic bomb.3

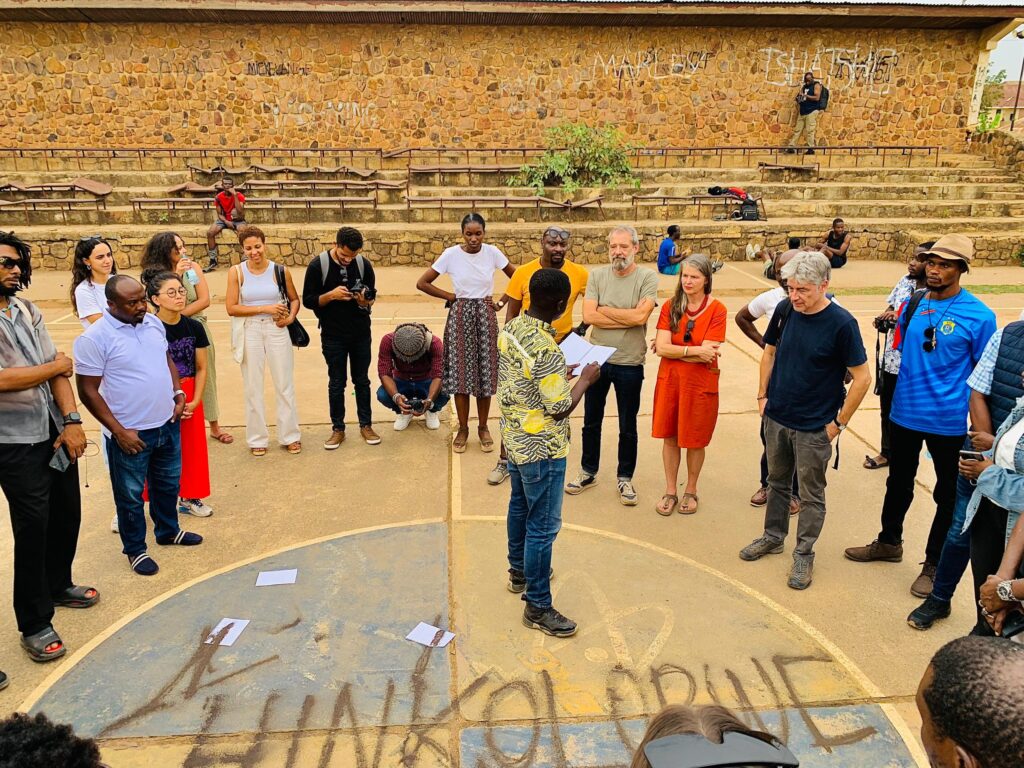

Takeuchi: Yes. The biennale itself was started in 2008 by Atelier Picha, an artists collective founded in Lubumbashi. This was the eighth biennale. I presented my work as part of a coalition with two other artists, Roger Peet from the United States and Sixte Kakinda from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Our exhibition Shinkolobwe: Between Power and Memory examines the overlooked history of the Shinkolobwe uranium mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a former Belgian colony. Shinkolobwe is located in the Katanga region, about 100 kilometers from Lubumbashi, where the biennale took place. This mine supplied the uranium used in the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as in thousands of other nuclear weapons. Katanga borders Zambia, a former British colony, and the history of uranium mining in Shinkolobwe is entangled with both British and Belgian colonialism, along with the exploitation of local resources and labor. In the exhibition, I presented my work Refuturing the Soil 2: Mapping the Other Side of Modernity and Peace, Guided by the Radioactivity of Shinkolobwe’s Uranium Ore (2024), which focuses on the colonial history and the erased memories of local Congolese people’s exposure to radioactive materials (Figures 10, 11, 12).

Figures 10, 11 Toshie Takeuchi, Refuturing the Soil 2: Mapping the Other Side of Modernity and Peace, Guided by the Radioactivity of Shinkolobwe’s Uranium Ore (2024), Lubumbashi Biennale 2024. The archival images from ©Collection RMCA Tervuren, ©RMCA Tervuren/Stalin, ©Sofam, ©Koushi Akeda, ©Hiroshima city archive, ©Brussels Royal Library, ©Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and United States Army.

Figure 12. Exhibition View, Shinkolobwe: Between Power and Memory, Lubumbashi Biennale, 2024. Works in the photograph include Toshie Takeuchi’s Refuturing the Soil 2: Mapping the Other Side of Modernity and Peace, Guided by the Radioactivity of Shinkolobwe’s Uranium Ore (2024), Roger Peet’s Dig Up The Sun (2023), and a banner that auto-workers in the USA used to display their solidarity with the workers at Shinkolobwe (2024).

Figure 13. Drawing performance by Sixte Kakinda, 25 October 2024. Lubumbashi Biennale.

Ikeda: The work Refuturing the Soil 2 consists of one hundred and twelve postcard-sized photographs. Your work attempts to imagine the erased experiences of Congolese miners and their families while also presenting the postwar promotion of “peaceful” use of atomic energy.

Takeuchi: The work combines my drawings on existing postcards, my photographs of autoradiographs of uranium samples borrowed from a descendant of a chief of Union Minière du Haut-Katanga, archival images, satellite images of the mine over time, and my recent documentation in Hiroshima. Some of the archival images are from the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, where nuclear energy and comfortable consumerism through new technology were promoted. In the same venue, Congolese people were displayed as part of an ethnological exhibit—just two years before Congo gained independence in 1960. One image I used shows a sculptural representation of two Congolese men at the fair, which the Belgian sculptor Arthur Dupagne described as depicting the “strength and youth of Congo.” I contrasted this with images of Congolese children working barefoot in the radioactive mine. Many local people were likely exposed to radioactive ore and contaminated water, suffering severe consequences.

Shinkolobwe’s uranium ore was exceptionally potent, with an average uranium oxide concentration of 65%, compared to a maximum of 1% in most uranium ores found elsewhere. However, no archives document the miners’ exposure to radioactivity at Shinkolobwe. Union Minière still withholds some key records. To address this gap, I made drawings on their promotional postcards, imagining what it must have been like for workers under such conditions.

I also included images from the 1958 Hiroshima Reconstruction Exposition (Hiroshima Fukkō Hakurankai), which strategically positioned victims of atomic bombs as active promoters of nuclear energy. The fact that the Brussels World’s Fair and the Hiroshima Reconstruction Exposition occurred in the same year is no coincidence. Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Shinkolobwe are deeply connected through “parallel” histories—the atomic bombings would not have happened without the uranium mined in Congo.

People in Japan may not be familiar with Congo’s history, but through this work, I aim to address the systemic issues of exploitation, resource extraction and the erasure of local sufferings tied to imperialism, colonialism, and capitalism, drawing connections between Japan and Congo.

Ikeda: I think your connection with Congo might not be clear without mentioning your experience of living in an occupied Congolese Embassy in The Hague. Would you explain what you did?

Takeuchi: Squatting was quite common in the Netherlands until 2010, when the government passed a law criminalizing the practice. In response to this legal change, a group of artists and squatters occupied the abandoned Congolese Embassy, which had closed due to financial problems and political instability in the Democratic Republic of Congo. I lived there for about five years, from 2011 to around 2016. This experience provided me with critical insight into the privileges enjoyed by leftist artists in the West, including myself, who could live under the immunity of diplomatic territory belonging to a country struggling with political and economic dysfunction. I created a film reflecting on this experience.

While living there, I began researching Congo’s history. A conversation with a Congolese individual who expressed his dream of walking from Congo to Hiroshima, given their shared nuclear histories, inspired me to further explore the connection between the two countries.

Ikeda: The theme of working in a collective seems to be an important one in our conversation today. I know some artists and even scholars now work collectively. Could you share why working as part of collective is important to you?

Takeuchi: I began working in collectives when I started living in the former Congolese Embassy in The Hague. Even when I present work as my own, it is always created through interaction with and inspiration from others. I don’t believe anyone produces anything entirely on their own. Individualism, in my view, denies relationality, and I see that as a form of arrogance. For me, art is a process born from relationships—with people and materials—and that must be acknowledged.

While I have experienced toxic collectivism in Japan, I strive to foster more organic and meaningful relationships through collaborative art-making. I have also observed a disconnect in some contemporary art between the conceptual dimension of a work and the labor required to produce it, which I believe deserves greater attention.

Ikeda: That’s very interesting. I am teaching Chinese art right now, and we discussed that very idea when examining Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds. He created an installation with millions of porcelain sunflower seeds, but the workers in Jindezhen who made them didn’t understand why they were making what they were making.

Takeuchi: I actually admire Ai Weiwei’s art, but it’s true that we should be more critical of the compartmentalization of labor in capitalist society. Before becoming an artist, I worked in a corporate setting where it was impossible to grasp the bigger picture of what the company was doing or the consequences of my work. When we consider decoloniality, I think that working in a collective is almost the only way forward. We need to understand the relationships between supplier and supplied, and between the land and its people. Moving beyond the violent histories of colonialism, racism, and the erasure of modernity requires recognizing that individual creation is a myth. We must acknowledge our relationality. As a practitioner of collective or community art, I believe in taking responsibility for transparency and creating space for others to contribute. I see this approach as the antithesis of the never-ending imperial and colonial system and its products. That is what I want to do with my art practice.

[Ed. Note: This article was originally published with the title: “Artist Toshie Takeuchi in Conversation with Asato Ikeda: From Palestine, Japan, to Congo”.]

Notes:

- For more on the artist and her works, see https://www.toshietakeuchi.com/; https://www.instagram.com/toshimoshi.toshimoshi/

- Refaat Alareer, “If I Must Die” (2011):

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze —

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself —

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up above,

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love.

If I must die

let it bring hope,

let it be a story. - For another interview by Asato Ikeda with artists who work with uranium, see On Uranium Art: Artist Ken + Julia Yonetani in Conversation with Asato Ikeda.