Abstract: Who is allowed to practice medicine? This question recurred in different forms throughout Japan’s modern era, reflecting fundamental changes in how people provided and received medical care. This article explores one key issue that underlined this question: a persistent doctor shortage, whose causes and form changed over time—from the late wartime era, through the immediate postwar rehabilitation years, to the era of rapid economic growth. Rather than focusing on issues of policy, the article examines personal histories, revealing how shortages led to various doctor substitutes, some legitimate and some not, in a process whereby doctor care came to be seen as a basic right.

Keywords: Doctor Shortage, Postwar Japan, Medical Licensing, Rural Japan, Okinawa

Who is allowed to practice medicine, and in what capacity? What is the relationship between medical licensing and skill? In postwar Japan, discussion around these questions was inextricably linked to what was often referred to as the doctor shortage problem (ishi busoku 医師不足). During the final years of the Asia-Pacific War (1937–1945), the Japanese military enlisted an ever-growing number of doctors, creating shortages at home. To meet this demand, medical education grew shorter, and standards dropped. After Japan’s defeat, under the American occupation, medicine underwent demilitarization and broad reform, reshaping medical practices as well as the criteria for practicing. Yet, concomitantly, the population faced a potential humanitarian disaster as a result of the ongoing impact of the destruction of war. Every capable hand was needed to provide medical care, even at the price of turning a blind eye to the absence of formal accreditation. Only decades later, when Japan began to enjoy a culture of plenty, did medical quality—and the power of a license to ensure it—rise to public attention and become a matter for debate.

At the center of these debates were individuals who doctored the population without the title of doctor. I refer to this phenomenon as medical workarounds. During each historical stage—war, occupation, and reconstruction—medicine underwent reconfiguration, which included a redefinition of its professional boundaries. Change, however, took time, while the demand for medical services on the ground remained urgent. The gap between changes that would improve the future and current needs led to the emergence of workarounds—ways of practicing medicine beyond the official paths of training and licensing.

These non-doctors answered a genuine need, providing help to numerous people who had no other recourse and earning reputations as respectable professionals. In certain instances, particularly during the period of rapid economic growth, some referred to them as “quacks” or “charlatans” (nise isha 偽医者) to discredit and belittle them, as they challenged the professional boundaries of the accredited medical system. There were also cases of non-doctors who indeed caused harm by offering substandard services under false pretenses or attempting treatments they had no skill to provide. Referring to non-doctors as quacks, however, obfuscates the broader significance and varied nature of these people and the services they provided. As the article reveals, the differences between the licensed and unlicensed could be blurry, with some non-doctors possessing equal or even superior skill when compared with licensed counterparts. And in Okinawa, non-doctors were also licensed.1 Examining the actions of this broad group within the framework of medical workarounds rather than quackery provides a better understanding of this largely overlooked history of medicine in action.

One reason this history has gone largely unnoticed is its unofficial nature. In most cases, non-doctors did not operate as an organized group within a formal, documented framework. Instead, their history appears in personal stories, which powerfully reveal lived experiences and daily realities of life that typically escape regulatory records. Accordingly, each section of the article focuses on the personal story of one individual, based on interviews and memoirs—rare sources, many of which are rapidly disappearing. For a significant period, the wartime generation refrained from sharing their life stories, and now, with the passage of time, fewer and fewer remain to do so.

Like the sixteenth-century miller Menocchio, whose story reveals the untapped world of early modern rural Italy, underscoring the strengths of microhistory (Ginzburg 1980), each protagonist serves as a window for understanding a broader reality. Positioning the stories within the historical context and carefully examining the public debates that surrounded them thus enables us to understand the unintended consequences of medical change and how people’s expectations altered with it. It also underscores the enduring effects of war on the history of medicine in Japan decades after the Asia-Pacific War ended.

Finally, it should be noted what the article leaves out. In another medical workaround, public health nursing in Japan developed from the early twentieth century largely to compensate for limited access to medical services in far-flung rural locations. However, unlike non-doctors, public health nurses were perceived as a distinct branch of nursing rather than doctor replacements, and worked within an accredited medical system (e.g., Ishihara 1967, 58–68; Kawakami 2012, 38–46). Thus, they deserve a separate, in-depth examination that is beyond the scope of this article.

Wartime Legacies: The Doctor Shortage

Yamanaka Kōichi was born in Tokyo eleven years after the end of the Meiji era (1868–1912), when its major reforms were ripening and began to bear fruit.2 The Meiji era was a transformative time in Japanese history, including in the field of medicine. Recovering from the threat of Western imperialism and a civil war, the Meiji government sought to build Japan as a centralized nation-state with a modern, regulated, and systematic medical system. As early as 1874, the Meiji government promulgated a series of nationwide medical laws, the Isei (医制), which set standards for medical education based on those of the Euro-American West, especially Germany. It also required a medical license to practice (see, e.g., Burns 1997, 705; Kim 2014; Shinmura 2006, 226–28). This was not the case in the preceding Edo period (1600–1868), when there were numerous paths to the practice of medicine.3

Instating a licensing system was part of a broader government attempt to designate those who were allowed to practice medicine according to a Western benchmark. The majority of those who provided medical services at the time practiced various Sino-Japanese forms of medicine, now lumped under the term kanpō (漢方). To weaken and even eliminate them in favor of Western medicine, the government did not simply illegalize kanpō. Rather, it required kanpō practitioners to obtain a license by passing a national exam whose subjects, such as anatomy and physiology, were exclusively Western, thus forcing them into a Western framework (Sakai 1982, 420). To prevent immediate medical shortages, while providers underwent training, the authorities temporarily allowed those who were already practicing kanpō to continue doing so (Sakai 1982, 422). In the long run, however, licensing served to enforce medical reform.

By the time Yamanaka was born in 1923, biomedicine, backed by the state, had grown increasingly prominent. Granted, by adapting to the new requirements, various forms of medicine continued to coexist within a lively medical marketplace, and surveys reveal that most people continued for decades to turn to over-the-counter drugs when they were ill, rather than seeking a more expensive doctor consultation. However, doctor visits did gradually become part of people’s lives as well (Suzuki 2008, 521, 524–31). This was particularly the case in the military, which was one of the main organizations to promote Western medicine (e.g., Bay 2012). From 1873, it included a medical department that provided medical services to soldiers who were sick or injured, in accordance with Western military and medical principles (e.g., Harari 2019, 1146–1147). Since general conscription was introduced at the same time, and since the scale of conscription grew over the decades, large numbers of men experienced Western medicine during their military service (e.g., Jaundrill 2016; Katō 1996).

Throughout, the government continued to view biomedical doctors as the leaders of the field, so much so that it considered remote places with no doctor, often referred to as “doctorless villages” (muison 無医村), to be in need of intervention. Although there were relatively numerous doctors in Japan by then, they tended to reside in urban areas where it was easier to open private clinics, which formed the foundation of the healthcare system. The result was a geographic medical imbalance, which as we shall see, recurred in the Postwar era. The concern surrounding this imbalance grew stronger in the interwar period, as Japan, like many other states, prepared for the possibility of total war, and each and every citizen came to be seen as a potential soldier or laborer and had to be kept healthy. The government thus formed policies aimed at improving the population’s health and saw doctors as crucial in their implementation across the country (Shinmura 2006, 271–72).

When Yamanaka began his medical studies in 1943, Japan waswell into the Asia-Pacific War, which caused a further shortage of doctors in the military and throughout the country. Yamanaka, the third of six children of a doctor, did not particularly wish to become a doctor himself. However, his eldest brother died of acute pneumonia and his second brother entered the insurance business, leaving to him the duty of studying medicine and taking over their father’s private practice. Studying medicine also offered certain advantages in wartime. It postponed enlistment and gave doctors the rank of high officer from the start, sparing them the bullying and other hardships so many soldiers experienced in their first year. (On bullying in the military, see, e.g., Endō 1994, 264–75. On doctor military ranks, see Rikujō jieitai eisei gakkō shūshinkai, 295–98).

And the military needed an increasing number of doctors. Since the War in China began in 1937, the military was concerned that the number of military doctors would not meet the growing demand, and considered various ways to expand their numbers. This need became even more pressing from 1941, when Japan entered the Pacific War which opened numerous additional fronts (Hashimoto 2008, 122–24). Although the war began with swift victories for Japan, by mid-1942 the tables had turned. Japanese forces were losing many battles, supply lines were susceptible, and the condition of the troops deteriorated (Yoshida 2018, 16–22). Yet the military continued to expand enlistment (Katō 1996, 240–60), including of doctors, which in turn created a deficit of doctors at home, in both urban and rural areas. While in 1937 there were 61,799 doctors in Japan, by 1942 the number had dropped to 50,677, and by 1945 to only 12,812 (Banshōya 2013, 136). War turned doctor shortages into a national issue.

One way to tackle this worsening undersupply was to produce new doctors quickly, which affected the nature of medical education. Since the late Meiji era, a person wishing to become a doctor could study either in a university or in a professional medical school (Sakai 1982, 430–31, 434–41, 542–43). Most medical students chose the latter, as they offered a shortened period of study, and required fewer years of prior schooling: universities required a higher-school education, whereas professional schools required only a middle-school education (Amano 2016, 123–25; Ogawa 1972: 9; Sakai et al. 2010, 342; Sakai 1982, 543; Shinmura 2006, 271–72; Fukunaga 2014, 377; Shillony 1986, 770).4 Given this disparity in popularity, the military recognized that simply increasing the quota of university medical students would not fix the problem. Instead, in 1942 the Ministry of Education established national and encouraged the establishment of private provisional professional medical schools (臨時医専 rinji isen) (Hashimoto 2008, 124). Yamanaka intended to follow the longer route of a university medical school, and so he enrolled in its preparatory school and began the three additional years of prerequisite schooling. His story, however, reveals that the arduous final years of the war ultimately lowered the bar even in university medical schools, blurring the differences between the two routes. While formal medical studies, like medical licensing, remained a requirement for practicing medicine, the paths towards them became less demanding than in peacetime.

During his first year, Yamanaka studied various subjects that were intended to provide him with a foundation of general knowledge, as well as more specific subjects needed for medical studies, including physics, ethics, and Latin and German—the languages of medicine since the Meiji era (see, e.g., Kim 2014). But by 1944, Japan’s situation had deteriorated further, and the demand for workers in military industries was urgent. With more and more men enlisted, new groups were mobilized to work in industry, including women and students (see, e.g., Havens 1978, 103, 110, 112). All the students in Yamanaka’s prep school were sent to work at Toshiba’s car factory, which had been converted to manufacture weapons such as antiaircraft guns and artillery. It was nearly impossible to study under such circumstances. At three o’clock every afternoon, the students had a thirty-minute break devoted to attending class in a small room. But the work was so physically exhausting that they were too tired to absorb any information. They returned to their school only a few times during Yamanaka’s entire second year. Then the school cut the third year entirely, graduating all its second-year students. Yamanaka entered a university medical school (the current Nihon ika daigaku 日本医科大学) directly afterward, with only one-third the necessary preparation.

In late January 1945, shortly after Yamanaka entered the university, Allied aerial bombing of the Japanese mainland intensified. Yamanaka’s school was almost completely destroyed (see, e.g., Ishikawa 1992, 44–45). The students were left without a building to study in and instead moved to Tsuruoka in Yamagata prefecture. Classes were held in an evacuated elementary school near a large hospital. Yet, studying was still a challenge. Tsuruoka was a center of production, notably of rice and sake, but because the military had enlisted many of the local men, there were few workers. Thus, besides studying, the students packed goods, moved crates, and helped in other ways. Classes were limited to lectures. Usually, Yamanaka explained, subjects such as biochemistry, biology, and bacteriology included a practical component, presumably in a lab. But there was no medical equipment available and no space appropriate for conducting experiments. The only class that was not based solely on lectures was anatomy, since bodies were brought in from the local hospital for students to dissect. There were no clinical studies, either. Yamanaka recalled that this was typical of medical studies at the time, since so many schools and hospitals had been bombed. Indeed, disastrous air raids burnt to the ground 40–100 percent of numerous Japanese cities (Gordin 2007, 21–22). This included educational and medical facilities, forcing the use of alternative structures (Fukunaga 2014, 344–45).

Ultimately, the war ended before Yamanaka finished his medical studies. He was still in Tsuruoka when Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945. Rather than going home for the summer break, he and a few classmates decided to stay and observe doctors at work at the large local hospital, to compensate a little for their lack of practical studies. It took him over a year to return to Tokyo, since the burnt universities and professional schools had to be rebuilt before they could welcome their students back (Sakai 1982, 544). In mid-1946, his school moved to a former military building in Kōnodai in Chiba prefecture.5 Only in the fall of 1947 did the school finally return to Tokyo. Even then, with the war over, Yamanaka could not fully devote himself to his studies. Hyperinflation in the immediate postwar years left many Japanese struggling to survive (Dower 2000, 112–120), and Yamanaka’s family was no exception. He therefore took part-time medicine-related jobs while he was still in school. He found these jobs largely through his father’s circle of medical acquaintances, but they were open to him also because of doctor shortages, which continued also after the end of the war.

Admittedly, by that time, there were more doctors in Japan than in wartime. By 1946, the number of doctors had risen to 65,301, and by 1947, to 70,636. This rise can be explained by a few factors: Japanese civilian doctors who had practiced around the empire repatriated after the war ended; many of those who began studying medicine during the war graduated by the time it ended; and military doctors were discharged and returned to Japan, often opening private practices (Banshōya 2013, 136–37). However, the number of those in need of care multiplied as well.

By the time of Japan’s surrender, nearly three million Japanese people were dead (Yoshida 2018, 23–24). Millions more were stranded across the empire, sometimes for years, until they repatriated, bringing with them various health problems and infectious diseases. Millions within Japan were homeless and basic infrastructure was severely damaged. Thousands of children were orphaned. The surviving population was sick, injured, and weakened from years of severely reduced caloric intake, particularly in urban areas; wartime food shortages grew even worse after defeat due to crop failures and the loss of the empire as a food source (Aldous and Suzuki 2012, esp. 53–61; Dower 2000, 45–64). Thus, although the end of the war finally halted the lethal bombings of Japanese cities, bringing relief, in many ways the civilian population became more vulnerable. Consequently, despite the general increase in the number of doctors, and the fact that they concentrated in cities where the demand was now greatest, the overall ratio of doctors to patients did not significantly improve from the final war years (Banshōya 2013, 137, 144–45).

With demand for doctors surpassing the available supply, Yamanaka began working a few days a week in busy doctors’ clinics, assisting in surgical and obstetric cases. In addition, he worked as a night guard in a hospital near Shinjuku, from which he could commute to school the next morning. Although his job was to patrol the hospital, and although he was still an unlicensed student, he was asked to treat patients who arrived during the night after getting into drunken brawls or drinking methyl alcohol. Alcoholism and drug addiction spread among the urban population following Japan’s defeat, causing numerous social and medical problems. Further, the dearth of basic ingredients led many to consume methyl alcohol-based drinks, which claimed hundreds of lives and caused many cases of blindness (Dower 2000, 107). Yamanaka thus played a role in bridging the disparity between the number of doctors and that of patients, concomitantly contributing to his family’s income.

In the spring of 1948, Yamanaka graduated. He then took a national medical exam, which was required of all medical students apart from those who graduated from a select list of schools, and then underwent practical training at a university hospital, which was required of all graduates from 1942 on (Sakai et al. 2010, 341, 343). Numerous extreme events took place from the time Yamanaka began his studies, creating the illusion that he had studied for many years, but in reality, his medical training lasted only a little over two years. Yamanaka recalled a conversation he had with his classmates one evening when they all went out drinking. Some wondered whether it was right for them to practice with so little education and experience. Others replied that they were now licensed and would do their best from that point on.

Yamanaka worked as a general practitioner in a private practice until he was 83 years old, and indeed helped countless patients, while adapting to the numerous changes the medical world underwent throughout this long period. And yet, so many years later, he still carried with him a sense of loss concerning his education: “To use a somewhat exaggerated expression, I felt inferior. Even now” (Yamanaka 2014). This statement can be seen as a testament to Yamanaka’s modesty, but it also demonstrates the long-term effects the war had on medical practice in Japan. Not only were there too few doctors in the years immediately after the war, many of those who began working at that time—and continued to work for decades—also started out with very little knowledge and skill. Whether trained in the provisional professional medical schools created as an emergency measure, or in the more established university medical schools, the quality of medical education was significantly diminished by the war.

The medical license, established during the Meiji era to systematize and Westernize medicine, remained a prerequisite for medical practice even in the final wartime years and immediate postwar period. However, as Yamanaka’s story illustrates, in the chaotic circumstances of war and in times of urgent need, the criteria for obtaining it became laxer. Some providers could begin practicing in certain capacities before meeting even these lower standards. This gap between medical supply and demand continued long after the war ended, as did the need for medical workarounds. An additional component contributed to this need, one that changed the postwar Japanese medical world, medical education, and licensing criteria—reforms led by the American occupying forces’ General Headquarters (GHQ).

Filling the Postwar Medical Gap: Unlicensed “Doctors”

When General Douglas MacArthur arrived in Japan in August 1945, his famous corn-cob pipe in his mouth, the mission before him was formidable indeed. Under his leadership, the American occupation forces rebuilt their former foe as a demilitarized and democratic nation. Starting with political and military affairs and extending into other aspects of life, such as culture and education, the GHQ led broad reforms (see, e.g., Takemae 2002). None of the changes could have taken root, however, had Japan suffered a large-scale humanitarian disaster under the GHQ’s supervision. Accordingly, the reforms also encompassed the restoration and demilitarization of public health and medicine. The GHQ’s wide-ranging reforms included vaccination campaigns; improved sanitation, nutrition, and other measures to prevent epidemics; reshaping hospitals and pharmacies to make them more efficient, standardized, and accessible; and expanding national health insurance coverage (Aldous and Suzuki 2012, chs. 3–6; Sugiyama 1995, 80–93, 190–208; Sugita 2007, 167–71).

Ironically, reforms contributed to the doctor shortages as the GHQ purged military doctors from the public medical system. Military hospitals and medical facilities were desperately needed, as so many civilian facilities had been destroyed by bombs or forced to close their doors when their doctors were mobilized. However, they also represented a strong link to the recent military past: they exclusively treated servicemen and their families, and they were staffed by military and military-affiliated personnel. To sever this tie, Crawford Sams, the head of Public Health and Welfare within the GHQ, nationalized all military facilities and turned them into public hospitals. They were now to admit both civilians and former servicemen, and they had to fire former military doctors who ranked above first lieutenant (Fukunaga 2014, 345, 364–65, 366–67). These doctors often opened private practices instead, but their elimination from the hospitals created a demand for civilian doctors to replace them.

In addition, in response to the drop in the quality of medical education that resulted from the war, the GHQ reforms also aimed at reshaping medicine more broadly, starting with medical education. Between 1946 and 1948, Sams, together with a Japanese committee, initiated a series of reforms in medical education, which ultimately included a requirement that all medical school students first complete high school.6 Medical school was to last six years, and the curriculum was to emphasize experimental and clinical studies rather than theoretical lectures. Only medical schools with appropriate facilities were allowed to remain open. Of the 46 professional schools, 29 managed to upgrade their facilities and become accredited universities, and the rest closed. And in a symbolic shift, medical studies emphasized English over German (Fukunaga 2014, 356, 377, 379; Amano 2016, 254–58). Upon graduation, students had to complete a medical internship, and then all of them had to take a national medical exam. Once licensed, doctors were required to undergo two further years of clinical training in a hospital or university lab (Sugiyama 1995, 81–82. For more also see Hashimoto 2008, 131–98). Yet, the new generation of doctors that was to emerge from these reforms could begin practicing only well into the 1950s and, according to Banshōya (2013, 133), became the majority of doctors only in 1965. As in the case of the Meiji reforms, implementing change took time.

The reforms thus exacerbated the existing doctor shortage, generated by war because soldiers were so often injured or exposed to infectious diseases. But this shortage lingered after the war ended despite the replenishment of doctors, in part because as noted above the population was even more vulnerable, increasing the demand for medical care. Meanwhile, the wartime response—lower medical standards in order to quickly produce more doctors—bred the postwar counter-reforms to raise the quality of doctors, and this longer training process created yet more shortages. But people needed medical services immediately. And so intermediary solutions developed on the ground.

Haraoka Isamu was born two years before Yamanaka, in 1921, and enlisted to an artillery unit in the Japanese army in 1941. Throughout the war, Haraoka served as a unit medic. Medics (eiseihei 衛生兵), alternatively known as corpsmen or military orderlies, were soldiers whom the military trained to become medical care providers. Unlike doctors, they usually had no medical background or experience before enlistment. Rather, the military trained them to provide emergency care on the battlefield, prevent diseases, tend to the sick, and assist doctors in base clinics and hospitals.7 Had he enlisted two years later, when Japan’s situation was rapidly deteriorating, Haraoka would have received brief and haphazard training at best. But at this stage—the very beginning of the Pacific War—the triumphant Imperial Japanese military medical system still functioned properly. Consequently, Haraoka went through six months of military training followed by six months of medical training (Haraoka 2014).

His training took place in Keijō (Seoul), Korea. Each day he commuted from his unit to a well-equipped military hospital, where he attended both theoretical classes, such as anatomy, taught by military doctors, and practical classes, such as bandaging, taught by non-commissioned medic officers. In addition to anatomy, medics learned how to tend wounds and injuries (e.g., how to set splints, antisepsis methods) and other traumas (e.g., frostbite, burns, poisoning); how to convey patients according to their condition, both on stretchers and on their person; how to identify and prevent the spread of various infectious diseases (e.g., cholera, malaria, tuberculosis); how to detect and provide care for other diseases and medical conditions that were prevalent in the military (e.g., acute gastroenteritis, beriberi, inflammation); and even some basic pharmacology ([Rikugun imukyoku] 1940).

After completing his training, Haraoka remained in Korea, where he served for about two years as a medic. But in 1944 he was transferred to a different unit and sent to Burma. On the way there, an American submarine sank his ship, and about half of the men drowned. Haraoka was rescued by a navy boat, but because of the many hours he had spent in the water, his hearing was permanently impaired. He spent the rest of the war in a struggle to survive. Japan’s position was deteriorating and, like so many other Japanese soldiers, Haraoka and his unit were stranded across the empire with little or no supplies to sustain them (see, e.g., Yoshida 2018, 28–41). For all his training, without food or medicine there was little he could do to help the numerous soldiers who contracted malaria or suffered malnutrition (Haraoka 2014). As a result, when Japan surrendered, Haraoka felt relieved. After two years as a British prisoner of war, he finally returned to Japan (Haraoka 2012; Haraoka 2014).

Life was still very difficult in 1947 Japan. As noted above, most people struggled to make ends meet. Moreover, Haraoka was part of a wave of about a million soldiers and civilians who repatriated that year from various parts of the former empire and had to find their place in a new Japan that was still recovering from the wounds of war (Dower 2000, 54). Haraoka’s first concern was thus to find employment. In the prefectures, which was where he lived, the doctor shortage remained especially acute. Even after expedited building efforts reopened many medical facilities and doctors were able to return to work, most still chose to live in cities (Banshōya 2013, 143–44). This proved lucky for Haraoka.

Opportunity came knocking not long after Haraoka returned to Japan, when a doctor he had served under during the war offered him a job at his dermatology clinic. Given his hearing loss, Haraoka saw dermatology as the perfect field, one where it was less important to listen to patients than to see their afflictions. Here he could make use of the knowledge and experience he had gained as a medic. After working in the clinic and gaining experience in dermatological care, he returned to his hometown, where another opportunity arose. Haraoka’s uncle introduced him to a professor at Kurume University who was searching for a dermatologist to treat patients, presumably at the university hospital. While working at the clinic, Haraoka memorized a dermatology textbook. Drawing from it and various other sources of information, he experimented at home and created ointments and dressings to treat the ailments of his many patients.

At the time, itinerant licensed doctors visited multiple hospitals and care centers, but they spent most of their time completing the additional training mandated by the GHQ’s medical reforms. As a result, they would sign their names to forms, but the person who actually saw patients was Haraoka. There was such great demand for his services that he eventually left the university and opened his own clinic in his hometown. He was not a licensed doctor, but he had knowledge and experience that arguably did not significantly differ from that of many doctors hastily trained in the final years of the war. He built a good reputation and most likely charged less than the few licensed doctors available, which mattered in those years of economic uncertainty.

After practicing for fifteen years, Haraoka was anonymously reported. What happened next is illuminating. The head of the regional health center came to inspect Haraoka and his practice, and thereupon instructed Haraoka to obtain a nursing license. Like doctors, nurses were regulated by a 1948 law requiring them to pass a national exam and earn a license to practice (Sugiyama 1995, 86). In the interim, rather than prohibiting Haraoka from practice, the inspector merely asked him not to take new patients apart from emergency cases. As requested, Haraoka took a course, studied, and passed the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s exam without much difficulty, all while tending his patients. Haraoka explained that he was on friendly terms with the official, who therefore treated him leniently. But the inspector’s decision also demonstrates the ongoing need for Haraoka’s services even two decades after the end of the war.

Why was Haraoka reported? Granted, he did not possess a license to practice, as required by the 1948 Medical Care Act. But this was true from the beginning, and Haraoka practiced for fifteen years to the satisfaction of his patients and the authorities. Only twenty years after the war ended was he reported. Haraoka contended that a disgruntled doctor who envied his success was the one who reported him, which implies that by then there were already competing doctors in the neighborhood. Haraoka attracted many patients, and the issue of accreditation was a weakness that a competitor could exploit.

But Haraoka’s story also epitomizes a broader change in medicine. In the early postwar years, Haraoka’s services were desperately needed for all the reasons noted above. But in the 1960s and 1970s, Japan experienced rapid economic growth, and people like Haraoka who met this need gradually came to be seen in a less positive light (Asahi Shimbun 1972c). A series of exposés in 1972 placed medical licensing at the center of social discourse and brought about a change in enforcement. The newspaper Asahi Shimbun described a medical association whose members were practicing as doctors around the country, even though they were nearly all unlicensed. These were former medics or doctors who had trained during wartime in Japanese medical schools across the empire, but whose local medical licenses were not accredited in the Japanese mainland. In 1947, the Ministry had instated a special exam to allow them to obtain a national license, but while about 800 such doctors repatriated, only 250 passed the exam. When the ministry offered an alternative exam in 1961 for those who had failed, only five of the 274 doctors who took it managed to pass. Most of those who either did not take the exams or failed found alternative occupations (Asahi Shimbun 1972a, 3). But the members of the association practiced as doctors illegally, including in emergency medicine (e.g., Asahi Shimbun 1971a, 10). In the wake of the ensuing scandal, the Ministry of Health and Welfare began a nationwide investigation together with the National Police Agency, revealing hundreds of additional unlicensed practitioners all over the country (e.g., Asahi Shimbun 1972e, 3; Asahi Shimbun 1972f, 1).

Based on over a hundred articles the Asashi Shimbun published on the topic between 1960 and 1980, it seems that many of the these practitioners, now referred to as “fake doctors” and “charlatans” (nise isha ニセ医者), were medical school graduates who had failed the national licensing exam, medical students who had never graduated, or people who had never attended medical school at all and were in fact ambulance drivers, medical technicians, or doctors’ spouses. They had forged their licenses or else used the chaos of war and reconstruction to obtain copies of others’ licenses and assume their identities. Haraoka’s case was different. His services were actively sought in 1947; when he opened his private practice, he served patients who had no alternative; but many continued seeing him even when alternatives became available. When he began, there was little to distinguish Haraoka from many licensed doctors, and while he practiced for two decades, most of the accused medical frauds practiced only a few years or months before they were discovered. Nonetheless, Haraoka got caught up in the scandal’s aftermath, which demanded a reexamination of what it meant to be a doctor.

If non-doctors were an ongoing phenomenon, existing between professional boundaries, why were they considered a problem meriting public attention specifically during the 1970s? There are a number of possible reasons. For one, an organized medical association may have had a stronger impact than individual practitioners, prompting a broad investigation and the revelation of an astounding number of additional cases.8 Another, more significant factor was the changed expectations patients had from their medical care providers during the 1960s and 1970s. Various popular movements rose to challenge traditional sources and structures of authority and to give a voice to vulnerable groups, including on health-related issues (e.g., Upham 1993, 337–44). Patients were emboldened to doubt doctors’ authority, notice suspicious behavior, and speak up. The newspaper reports reveal that the investigation conducted by the National Police Agency relied on people’s reports and local rumors (Asahi Shimbun 1972c, 3; Asahi Shimbun 1972d, 4). In the case of an emergency hospital that employed members of the dubious medical association, families of patients who were allegedly harmed or killed due to medical errors and negligence even established an organization to demand compensation (Asahi Shimbun 1972b, 10).

A third factor was economic growth. The new patient voice was strongest in cities, likely because of the different impact doctor shortages had on cities as compared with rural areas. Many of the articles claimed that the increase in medical fraud was the result of the “chronic doctor shortage” (manseiteki-na ishi busoku 慢性的な医師不足; e.g., Asahi Shimbun 1972f, 1). However, in urban centers, where most of the Japanese population lived, there was by now a surplus of both doctors and medical facilities, similar to the situation in the prewar period. Instead, the likely culprit for medical fraud in large cities was changing market forces. These cities had developed into medical hubs wherehospitals and clinics competed over both patients and doctors (Kumagai 1973, 5). One reason for this competition was prosperity and universal health insurance, which caused a sharp increase in the number of people seeking doctor’s appointments.

As discussed above, for decades, most of the population did not immediately consult a doctor when in need of medical assistance. Among other reasons, doctor services were expensive—but affluence and medical insurance coverage changed that. In 1972, the government further expanded welfare policy to provide free medical care for the elderly starting the following year (Takahashi 2019, 205). Thus, while there were more doctors than in the past, there were also more patients who could afford their services (Matsumoto et al. 2010). Some medical institutions knowingly employed unlicensed doctors to fill this growing demand, sometimes with detrimental consequences (e.g., Asahi Shimbun 1971b, 3; Asahi Shimbun 1971c, 9). Medicine became a flourishing business, and it needed doctors to thrive.

In major cities, doctor shortages were thus the result of a thriving culture of plenty and growing choice. Outside the big cities, however, particularly in remote, rural areas, doctor shortages resulted from the absence of medical professionals, a situation that remained largely unchanged from the prewar period. To tackle this issue, elaborate plans were put in place starting in 1950, aimed at creating a multi-tiered medical system, centered on large general hospitals in the prefectural capitals and smaller hospitals and clinics further from the center (Banshōya 2013, 141). But about a third of Japan’s prefectures did not even have a medical school, and plans to establish new ones encountered various difficulties (Hashimoto 2008, esp. 271–75, 279, 280–90). Moreover, doctors still preferred to work in cities for both professional and personal reasons. As medicine underwent increasing specialization, doctors became experts who knew a lot about one specific area and very little about anything beyond it. Treating one patient thus required a team of specialists, but in remote places, a doctor had to work alone (Kumagai 1973, 5). Doctors also noted how difficult it was to obtain the latest information and equipment in far-off locations, or to attend medical conferences and thus continue to be part of a medical community (Asahi Shimbun 1972d, 4; Asahi Shimbun 1979, 1). For those with families, the lack of cultural and educational opportunities in remote areas were a deterrent as well (Asahi Shimbun 1979, 1; Asahi Shimbun 1978, 2).

Many towns and villages had no medical doctors at all (e.g., Asahi Shimbun 1972d, 4). Some communities asked hospitals dozens of times to send a doctor to no avail (e.g., Asahi Shimbun 1972d, 4). In one case, an unlicensed doctor was supposed to work only two or three months until an alternative was found, but no licensed replacement ever was, and he remained (Asahi Shimbun 1972h, 18). And so, if a doctor finally agreed to come to such a community, the local population was so grateful that it did not ask to see his accreditation. Moreover, once a doctor was revealed to be unlicensed, the locals would remain with no one for a long time(Asahi Shimbun 1978, 2). Which, then, was the better option?

This question was echoed in a number of the articles, revealing a broader debate on how medical quality was to be evaluated. Could a license guarantee proper medical care? Articles reported cases of unlicensed individuals giving misdiagnoses and conducting major surgeries with no proper training, which resulted in harm to the patient and even death (e.g., Asahi Shimbun 1971a; Asahi Shimbun 1973, 11). Yet there were other cases where “fake doctors” were capable, empathetic, dedicated and efficient, so much so that their patients could not believe they were unlicensed even after they were discovered (e.g., Asahi Shimbun 1978, 2). Was a talented and experienced yet unlicensed doctor thus necessarily inferior to a licensed one? One article even noted that some of the unlicensed doctors had graduated from a medical school but failed the national exam. Were they significantly different from licensed doctors who had just barely passed the exam (Asahi Shimbun 1972e, 3)?Moreover, a medical license was for life, while medicine evolved over time. Some proposed a mandatory annual test to ensure that doctors were still physically and mentally competent and that they were not practicing under a false identity. But, in anticipation of opposition by the National Doctor Association, this measure was quickly rejected (Asahi Shimbun 1972d, 4; Asahi Shimbun 1972g, 22).

Horiuchi Shigeru, a famous psychiatrist who wrote under the pen name Nada Inada, suggested a very different approach. He argued that a license was a means to preserve doctors’ monopoly over the practice of medicine rather than to ensure quality care, and even allowed certain doctors to charge exorbitant sums of money for useless treatments (Nada 1972, 6). In fact, the 1948 licensing law stated, “Only a doctor is allowed to practice medicine” (Medical Doctor’s Act 1948, article 17), and defined “doctor” as a graduate of an accredited medical school who had obtained a doctor’s license—thus excluding practitioners of East Asian medicine, among others, similar to the Meiji-era reforms. It also placed very few restrictions on doctors once they received their licenses, based on the assumption that interference could damage their judgment and confidence, and thus curb medical progress. Instead, the path to becoming a licensed doctor became longer and more difficult, in the hopes that this would ensure quality care afterward (Banshōya 2013, 134). Horiuchi/Nada thus claimed that, far from being a standalone problem, unlicensed doctors and frauds highlighted fundamental problems in the healthcare system, and that, until these problems were fixed, doctor shortages would continue and, with them, non-doctors who filled the resulting gaps (Nada 1972, 6).

This discourse on the quality of medicine and the healthcare system was thus the result of the shifting realities of the 1970s. During the war and its aftermath, people’s main concern was survival. As the turmoil of the past grew more distant, and with increasing prosperity and broader insurance coverage, the mere availability of licensed doctors was no longer sufficient. They had to be considered capable as well. The debate surrounding medical workarounds thus reveals evolving perceptions and expectations of medicine. In remote rural areas, on the other hand, finding any medical practitioner willing to serve the population was still a challenge. Thus, doctor shortages persisted in both urban and rural settings, but in different ways. Horiuchi/Nada proposed a workaround by which some healthcare work would be formally delegated to talented and capable non-doctors, turning them into a solution rather than a problem. He noted that public health nurses already provided various medical services in remote areas, but that the law required them to get a doctor’s approval for certain procedures. Horiuchi/Nada favored expanding their responsibilities and independence (Nada 1972, 6). What he did not know was that his idea was already a reality in Okinawa prefecture, which was soon to return to Japanese sovereignty.

Not Doctors: Licensed Medical Service Men in Okinawa

When the Meiji oligarchs embarked upon their journey to transform Japan, one of their main goals was to turn it into an empire. Their many reforms were aimed at cancelling the unequal treaties foisted upon Japan by Western powers in the 1850s and ensuring that Japan would never again find itself subordinate to foreign empires. To do so, it was to become an empire itself, consolidating a Japanese “civilization” while imposing it upon others. The first step was the colonization of Ezo, renamed Hokkaido prefecture in 1869, and of the Ryūkyū kingdom, annexed as Okinawa prefecture in 1879 (e.g., Howell 2005, 7–8). The Japanese state instituted various policies to turn the new prefectures into a part of Japan, placing them under Japanese administration, law, and police; gradually exporting to them Meiji modernization; and ultimately assimilating the local populations (Howell 2005, 172–196; Kerr 2000, 397–401; see also Meyer 2020).

In the case of Okinawa, Japan also instituted public health and medical reforms in the 1880s, including vaccination campaigns, improved sanitation, building hospitals, and limiting yuta shamanic healing activities (Kerr 2000, 401–02; Maeda 2021, 46–47). It also opened a Western medical education program in 1885. The program, however, was active for only 27 years, producing 172 doctors, and the vast majority of these lived and worked in the main cities of Shuri and Naha. Consequently, in more distant areas, there were few or no doctors (Kinjō 1963, 602; Maeda 2021, 56–57). Okinawa is an archipelago consisting of over a hundred islands spread across around a thousand kilometers. Some small islands are secluded and difficult to access, leaving their populations with little access to medical care.The doctor shortage that existed in rural areas in the mainland was thus much more severe in Okinawa.

Besides the geographic challenges, the Japanese metropole—whose own medical reforms were just underway at the time of Okinawa’s colonization—perceived Okinawa as inherently different and even inferior to the mainland. Thus, by and large, as Masubuchi (2019) argues, Okinawa became the “periphery of the Japanese imperial state,” with healthcare and welfare services far behind those of the mainland (17). The limited availability of doctors, coupled with distrust and, as we shall see, limited economic means, meant that most people turned to local folk remedies in times of illness (Maeda 2021, 42).

Oyamori Chōmei grew up in this reality, which shaped his path as both patient and, eventually, medical caregiver. He was born in 1916 in Taketomi, a small island of about 600 people. Taketomi was at the southernmost tip of the Okinawan archipelago, far away from its main island and closer to Taiwan than to mainland Japan (Oyamori 2010, 32). His father passed away when he was only four years old. When he was 13, he broke his arm badly in an accident and was rushed on a boat to a tiny hospital on an adjacent island. While today his arm would have been saved, at the time the three doctors on staff decided to amputate it rather than risk gangrene. Oyamori thus grew up with only his left arm (ibid., 45–50). Ironically, this traumatic event spared him from being enlisted for the Sino-Pacific War years later, and perhaps saved his life.

Instead, in 1942 he began working at a small local clinic that provided medical services to the island’s population and also regularly visited smaller nearby islands. There was only a doctor, a nurse, and a pharmacist at the clinic, and Oyamori’s job was to help them all. He did administrative work, such as calculating payments and ordering medical supplies before they ran out. He also assisted in the medical treatments, which stirred in him an interest in medicine. In his spare time, he read the clinic’s medical books on topics such as diagnosis and treatment, pharmacology, internal medicine, surgery and dermatology. The doctor answered his questions about the reading and provided additional explanations (ibid., 152–53).

When the Battle of Okinawa began in March 1945, Oyamori was still working in the clinic. It was the final battle of the Second World War, and the only one to take place on Japan’s home islands, amid its civilian population. The combination of aerial bombardment and ground combat killed around 120,000 civilians and resulted in destruction that set Okinawa apart from the mainland for many years to come, (Hayashi 2005, 50). The fighting centered on the main island, so Taketomi did not become a battlefield, although, like many other places, it was bombarded. One challenge Oyamori’s clinic faced during the war was caring for refugees who evacuated to Taketomi. Many of them caught malaria, a health hazard in the Yaeyama islands of which Taketomi was part, and of Okinawa more broadly (see, e.g., Iijima 2009, 61–70).

Oyamori continued working in the clinic after the war ended, and through it had an encounter that changed the course of his life. Japan’s defeat put an end to its vast maritime empire, prompting the return of Japanese nationals to the home islands. One of these was a doctor who studied in Japan and had worked in Taiwan. When he returned in 1945, Dr. Sakiyama began working in the small clinic and became a mentor to Oyamori, teaching him a lot in a relatively short time. Not long after the defeat, the clinic was requisitioned, most likely by the US military government (Oyamori 2010, 75, 153–54).

Not only was Okinawa the only prefecture to experience direct warfare, it was also the only one to experience the American occupation directly. While the American military ruled mainland Japan indirectly, through a local Japanese government, and only after Japan’s capitulation, it had taken over parts of Okinawa, while the Battle of Okinawa was still taking place. Consequently, the United States Military Government began ruling it months before the defeat and continued to do so after it; in 1950 it was replaced by the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands (Sakihara and Todoriki 2004, 2). This meant that mainland Japan and Okinawa were each subject to different policies, legal systems, and medical and public health structures. As we shall see, the American administration took responsibility for health conditions on the archipelago from early on, including requisitioning existing structures. The purpose was, first and foremost, to protect American troops from infectious diseases, particularly malaria and sexually transmitted diseases (Masubuchi 2019, 17). Nonetheless, the American policies had a far-reaching impact on Okinawa’s health and medicine for years to come.

Leaving the clinic behind, Oyamori temporarily took a break from the medical world after the defeat, joining efforts to ensure an adequate food supply for the small island and even working in agriculture. Food became one of the main postwar challenges in Taketomi, particularly as many Japanese repatriates from Taiwan first returned to Taketomi due to its proximity. But in 1949 Dr. Sakiyama wrote to Oyamori to offer him a job at the Yaeyama Civil Administration Health Department Malaria Prevention Center, which ultimately became a general health center, treating various diseases. Oyamori accepted the offer and began working there as Sakiyama’s assistant, gaining knowledge and experience (Oyamori 2010, 72–80, 157–58).

The center surely played an important role in the community, given that the doctor shortage faced by mainland Japan after the end of the war was a severe scarcity in Okinawa. According to a 1949 survey conducted by the GHQ Public Health and Welfare Bureau, in 1948 mainland Japan had one doctor for every 1,165 people, whereas Okinawa had one for every 4,343 people (Sakihara and Todoriki 2004, 4). Although Okinawa’s doctor shortage predated the war, the war greatly exacerbated the situation by turning Okinawa into a battlefield. One-third of its civilian population died. Tens of thousands were wounded, and multiple diseases spread among the survivors. The island’s medical infrastructure, like much else, was destroyed. Most medical practitioners were killed; of 163 doctors, only 64 are believed to have survived. Some of these relocated to mainland Japan (Masubuchi 2017, 24; Sakihara and Todoriki 2004, 4).

As early as April 1945, even as the battle dragged on, the US military began providing free medical services to the injured and sick within the territories it occupied on Okinawa Main Island. After Japan’s defeat, the US military government, which ruled all of Okinawa, promulgated a Public Health and Sanitation Act to deal with the vast destruction. The law called upon all who provided medical services to continue treating and preventing diseases, including both licensed practitioners—doctors, dentists, pharmacists, nurses, and midwives—and “others”—former medics, acu-moxa practitioners, doctors’ assistants, and so on. This was supposed to be a temporary measure, but as doctor shortages persisted, particularly in remote places and isolated islands, the government used doctor assistants as primary care providers (Sakihara and Todoriki 2004, 3–8).

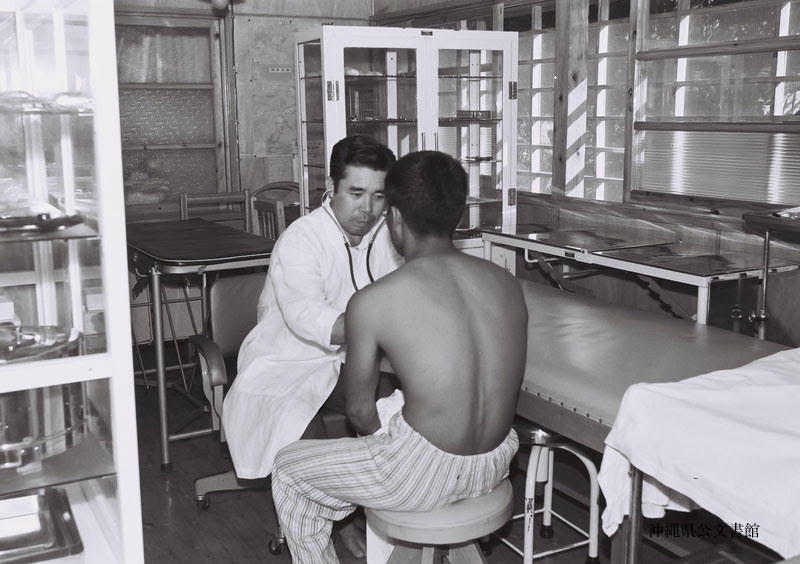

In 1951 the American administration made this system official by creating the “medical service man,” or ikaiho (医介輔). Ikaiho, sometimes called kaiho for short,had to possess at least three years of experience as doctors’ assistants; train for at least a year under a licensed doctor in subjects such as first aid, diagnosis, disease care, minor surgical procedures, and basic pharmacology; and pass a licensing exam. There was also a separate, related category of dental ikaiho (ibid. 8–10).9

While working at the malaria center, Oyamori took and passed the exam, and began working shortly after as a licensed ikaiho (Oyamori 2010, 158). He was one of the 126 ikaiho produced by this new system (Sakihara and Todoriki 2004, 9). For 57 years he served as the first line of medical care in various remote locations in the Yaeyama islands, helping numerous people. According to Oyamori, ikaiho were sent to various remote areas with small, very poor populations. The ikaiho had no facilities and thus usually used one room, or in Oyamori’s case, the entrance to his house, to see emergency cases. They also had little equipment and little money to buy a stethoscope, medicine, and other basic supplies. Oyamori built an examination bed by himself.

Ikaiho like Oyamori also earned very little, since the local people usually could not afford to pay the treatment fees. They often provided free care or received modest gifts of food instead of cash. Yet life was very busy, because so many people were sick and needed care. As the only medical care provider, an ikaiho had to be available at all times for any emergency, and often went on house calls as well. Moving about was difficult, since there were often no paved roads. Oyamori also visited small adjacent islands by boat (Oyamori 2010, 140, 143, 146–47). Miyazato Zenshō, who was also an ikaiho, used to provide treatments in his clinic by day and go around on his bicycle to conduct home visits in the evenings, using a flashlight since the roads were unlit at the time (Miyazato 2014).

Despite their limited means, ikaiho served as the first line of care and thus had the authority and freedom to provide a broad variety of treatments.But they were also limited by regulations that listed conditions and situations in which they were required to refer patients to a doctor’s care. For example, ikaiho were forbidden to administer X-ray exams, conduct major surgeries, treat certain diseases, provide psychiatric care, and prescribe certain narcotics and antibiotics. They were also required to refer serious cases to the local hospital, although they provided emergency care and initial diagnosis (Oyamori 2010, 138–39).

In short, ikaiho were licensed, trained, and experienced healthcare providers who were responsible for the health of their communities and performed tasks usually reserved for medical doctors as part of an organized and regulated system. As such, they were simultaneously sequestered from and part of a broader healthcare system. Ikaiho both replaced and worked alongside doctors. They maintained collegial relationships with them and with other medical personnel in the hospitals to which they referred their patients. Miyazato, for instance, described working closely with the local hospital and said that he was respected and appreciated by the medical community there. Nonetheless, he recalled one hospital doctor disparaging him as “fake doctor” (nise isha). Miyazato was very hurt by this. He was not a doctor, nor did he claim to be one. He was a licensed ikaiho, with a unique and important role that stood on its own (Miyazato 2014).

According to Oyamori, there were other such doctors who denigrated ikaiho, accusing them of not being versed in modern medicine and of being low-level medical practitioners. As a result, Oyamori claimed, ikaiho were even more careful, making sure to refer patients to a doctor if they had even the slightest doubt concerning their diagnosis and course of treatment. Moreover, they formed an ikaiho association, which hosted monthly lectures by members of the parallel doctor association in order to remainup to date on innovations in various medical specialties (Oyamori 2010, 147–48). In other words, there was occasional friction concerning the boundaries of professional responsibility, as people in mainland Japan feared would be the case, since ikaiho indeed broke the doctor monopoly to a certain extent. But, in general, the system worked quite smoothly, solving the fundamental problem of medical access.

As a result, ikaiho were valued and trusted members of their communities.10 When preparations began for Okinawa’s reversion to Japan, many feared the cancellation of ikaiho. With reversion, the legal system established under American rule was dismantled, and Okinawa was placed under Japanese law instead. This shift necessarily delegitimized existing structures and roles that did not align with Japanese law, unless an exception was deliberately made (see e.g., Iwagaki 2018). Lawyers, for example, had received their licenses from US Civil Administration and practiced according to its laws—which were nullified by the reversion. However, they were allowed to continue practicing as an exception, and even today they appear as special members of the Japanese Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA 2024).

Unlike lawyers, however, ikaiho had no parallel in Japan and no national association to join. They also contravened Japan’s Medical Doctor’s Act, which, as noted above, limited medical practice to licensed doctors with degrees from accredited schools (Oyamori 2010, 139). Communities were in danger of losing their medical care providers, and the ikaiho their livelihood and position in society. To prepare for this eventuality, Shinyashiki Kana, who headed the ikaiho association, went to Tokyo two years before Okinawa’s reversion to introduce the ikaiho system to the Japanese parliament and explain its importance. Ultimately, the Ministry of Health and Welfare allowed the ikaiho to continue practicing (Shinyashiki 1986, 42–3), but they limited the system to existing ikaiho (Oyamori 2010, 139). At that point there were 49 left (Sakihara 1987, 31). The last to retire was Miyazato in 2008. His hearing began to deteriorate, and he did not want to endanger his patients. At that point, there were also more alternatives, which allowed him to leave his position with a light heart, receiving accolades and appreciation from his former patients (Miyazato 2014; Okinawa Times 2009).

The ikaiho are one example of how Okinawa’s special status and history, as concomitantly part of Japan and distinct from it, created their own challenges as well as possibilities. From early on, Okinawa’s population had much more limited access to medical services, a dearth that reached crisis proportions as fighting on its soil inflicted many casualties. Both the shortages of doctors and the demand for their services were more extreme than in the mainland. However, the war also placed Okinawa under a different political rule, which resulted in different policies aimed at solving the humanitarian and medical crisis. The American administration’s semi-military nature gave it more freedom to initiate unprecedented steps. Moreover, it was unencumbered by pressures from local doctor associations, since there were so few doctors to begin with. All these factors allowed the creation of the ikaiho as an easier-to-train alternative who could serve areas that were beyond a doctor’s reach. However, once Okinawa reverted to Japan and its legal framework, the ikaiho’sdays were numbered. Practicing ikaiho were allowed to continue working, but only as a temporary remnant of the occupation. However, rather than changing Japanese law and expanding the ikaiho solution to the rest of Japan, the government ended the system, a decision primarily driven not by medical considerations but political ones.

Conclusion: The Rise of Doctors?

Non-doctors proliferated during transitional periods in Japanese modern history—the Meiji medical reforms, total war, the medical reforms of the American occupation, and the shift from poverty to prosperity. Each upheaval created particular medical and public health needs. Each also generated regional and national doctor shortages for distinct reasons, accompanied by the appearance of non-doctors as unofficial—and, in the Okinawan case, official—workarounds, to compensate for these shortages. By meeting an urgent need, non-doctors pushed the boundaries of medical practice and the division of medical labor, and highlighted a growing demand for doctor services. What could be seen as lying at the heart of these stories of medical boundaries, therefore, is the gradual rise of doctors to the center of the Japanese medical world.

Doctors were never the only medical practitioners available in Japan, nor necessarily the most important. Most people did not turn to them in times of need, whether because they preferred other approaches or because they simply could not afford their services. To this day, Japan’s thriving medical marketplace offers a multitude of medical solutions. Nonetheless, from the Meiji era, laws that determined the boundaries of medical practice gave preference to doctors and pushed them into the center of medicine and medical decision-making, as part of a decades-long effort to promote Western medicine and exclude those who did not align with it.

In other historical cases, too, the rise of scientific medicine, the standardization of medical education, and the implementation of licensing aimed to exclude practitioners who did not follow the new criteria (e.g.,Vankevich 2002, 220–23). In Japan, however, this medical change was not motivated solely by medical and professional considerations. Rather, one of the main driving forces from the beginning was war and its aftermath. Effectuated by the government, the Meiji medical reforms were part of a broader reconfiguration of Japan aimed at protecting it from external military threats. The military was one of the main promoters of medical reforms, and military doctors were the leading decision makers. Decades later, in the days of total war, the expanded military demand for doctors came at the expense of the home front, leading to a relaxation of medical criteria and an opening for the unlicensed. During the aftermath of war, doctor shortages continued in the face of massive numbers of injured and ailing people, while occupation-led reforms made the path to becoming a doctor longer and more demanding. Throughout these transformations, licensing officially maintained a doctor monopoly, but people turned to whomever they could afford and trust for the care they needed.

It was only in the 1970s, about two decades after the end of the war and the occupation, that prosperity and expanded health insurance enabled more of the population to afford doctors’ services. With this change, the public not only began to question non-doctors, but also reexamined the nature of doctor care itself. What made a doctor a good one? Such a question could rise to the fore because there was no longer an emergency, giving people leeway to examine quality, and because doctors became a prominent part of life, drawing broader public attention to the nature of their services. The process that began in the Meiji era now reached fruition.

The very different circumstances in far-off rural areas accentuate this process. With few or no doctors available, there was less impetus to scrutinize the quality of their care. Their absence also created more space for non-doctors, so much so that some suggested making their status official. Within an official system, non-doctors would reinforce doctors’ dominance from the boundaries. The Okinawan example demonstrates this argument. Okinawa’s unique wartime and postwar experiences exacerbated both the doctor shortage and the demand for medical services, while positioning Okinawa under a different legal framework. This distinct historical trajectory enabled the creation of the ikaiho as an official and licensed non-doctor. Ikaiho brought medical services normally provided only by doctors to a broader group of people across a larger territory, people who would otherwise have turned to local forms of medicine. However, when Okinawa reverted to Japan, rather than expanding the ikaiho system to the rest of the country, the Japanese government expanded its own doctor monopoly to Okinawa, bringing the ikaiho system to an end.

Today, as the Japanese population ages rapidly, doctor shortages continue to preoccupy Japanese authorities and society in a new guise and to prompt new solutions, which deserve separate, in-depth examination (see, e.g., Asahi Shimbun 2023, 19). The recurrence of this question, however, demonstrates how far it is from being solely a medical issue. Doctor shortages have consistently reflected broader challenges faced by Japanese society, which were underlined by changing social views and political structures, as well as regional differences. Throughout the examined historical period, the perception grew that access to medicine, and specifically to doctor care, was a basic right that needs to be ensured by the state. And thus, as new challenges continue to arise, they might necessitate renegotiation of the boundaries between different medical roles and the prominence of doctors, altering once again both medical practice and the daily lives of patients.

Acknowledgements: This article was the result of the help and support of many dear people, although I sadly cannot thank them all. First and foremost, my deepest gratitude goes to Haraoka Isamu, Yamanaka Kōichi and their families, for so kindly welcoming me into their homes and for sharing their precious stories with me. I dedicate this article to them. This work would not have been possible without the invaluable support of Michal Nissim Takahashi, Takahashi Hayato, Takahashi Yoshimitsu, Tadokoro Satoko and the volunteers of the Japan Veterans Video Archive Project (senjō taiken hōei hozon no kai 戦場体験放映保存の会). Very special thanks to the wonderful Gilly Nadel, Angharad Fletcher, Hadas Aron and Orly Lewis. I am also indebted to Alexandra Burykina and Yotam Gazit for their assistance, and to Tristan Grunow and the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments. Finally, I thank Ruti Harari for doing everything she could to help me write in very difficult circumstances. While the article benefited from the contribution of many, all possible mistakes are solely my own.

This research was supported by THE ISRAEL SCIENCE FOUNDATION (grant No. 312/21)

References

Anonymous. 1964. “医介輔 診療風景”[Ikaiho (at work): Scenes of Medical Care]. 医療・衛生 [Category: Medical Care and Hygiene]. 琉球政府関係写真資料025 (Ryūkyū Government Related Photos and Document 025). 沖縄県公文書館所蔵 (held by the Okinawa Prefectural Archives. May: photo no. 007058.

Aldous, Christopher, and Akihito Suzuki. 2012. Reforming Public Health in Occupied Japan, 1945-52: Alien Prescription? New York: Routledge.

Amano, Ikuo. 2016. 新制大学の誕生:大衆高等教育への道 (上)[The Birth of the New University System: The Path Towards Mass Higher Education, Vol. 1]. Nagoya: Nagoya Daigaku Shuppankai.

Aoki, Toshiyuki. 2009. “佐賀藩「医業免札制度」について”[The Saga Han Medical Practice Licensing System]. 佐賀大学地域学歴史文化研究センター「研究紀要」[Saga University Center for Regional Culture and History “Research Bulletin”] 3: 35–70.

Asahi Shimbun. 1963. “ニセ医師取り締まり強化:厚生省 今年もう44人”[Strengthening the Fake Doctor Crackdown: Already 44 Additional Cases this Year According to the Ministry of Health and Welfare]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Evening Edition, August 25: 9.

Asahi Shimbun. 1971a. “ニセ医者が2人も: 大阪の救急病院手入れ” [Two More Fake Doctors: Crackdown on an Emergency Hospital in Osaka]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Evening Edition, December 9: 10.

Asahi Shimbun. 1971b. “大阪でまたニセ医者―実はホルモン焼屋:大和病院夜間に診療、注射も”[Another Fake Doctor Case in Osaka —Actually a Grilled Meat Restaurant Owner: Conducted Medical Exams and Even (Gave) Injections on Nightshifts at the Yamato Hospital]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Morning Edition, December 27: 3.

Asahi Shimbun. 1971c. “斎藤前院長を逮捕:ニセ医師の救急病院”[Former Hospital Manager Saitō Arrested: The Medical Fraud Emergency Hospital]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Evening Edition, December 16: 9.

Asahi Shimbun. 1972a. “ニセ医者を一手に供給:元衛生兵らの同門医師会を追及” [A Single-Handed Supply of Charlatans: The Investigation of an Alumni Medical Association of Former Medics]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Morning Edition, January 9: 3.

Asahi Shimbun. 1972b. “地裁がカルテを検証:ニセ医者の斎藤病院 遺族ら賠償請求へ” [District Court Inspection of Patient Charts: The Medical Frauds of Saitō Hospital—Surviving Families Demand Compensation]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Evening Edition, March 16: 10.

Asahi Shimbun. 1972c. “あやしい医者‘総検診’:警察庁 風評もとにチェック” [Suspicious Doctors’ “Comprehensive Inspection”: National Police Agency Inspections Based on Public Rumors and Reports]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Morning Edition, January 15: 3.

Asahi Shimbun. 1972d. “ニセ医者の横行:医療制度も問題”[Widespread Medical Frauds: The Problem Lies Also in the Medical Healthcare System]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Morning Edition, January 21: 4.

Asahi Shimbun. 1972e. “ニセ医を全摘手術:厚生省都道府県に大号令”[Total Surgical Removal of Fake Doctors: The Nationwide Grand Directive of the Ministry of Health and Welfare]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Morning Edition, January 20: 3.

Asahi Shimbun. 1972f. “今日の問題:ニセ医者”[Problem of the Day: Fake Doctors]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Evening Edition, January 20:1.

Asahi Shimbun. 1972g. “定期的に資格審査を:ニセ医師対策で警察庁”[Periodic Qualifications Inspection: The National Police Agency’s (suggested) Countermeasure for Medical Fraud]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Morning Edition, March 28: 22.

Asahi Shimbun. 1972h. “偽名八つを持つ男:三重県のニセ医師 歓迎され居すわる”[A Man with Eight Aliases: Fake Doctor in Mie Prefecture, Welcomed and Took Residence]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Morning Edition, January 6: 18.

Asahi Shimbun. 1973. “盲腸の手術などもしていたニセ医師” [Fake Doctor who Even Conducted Surgeries like Appendix Removal]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Evening Edition, November 8: 11.

Asahi Shimbun. 1978. “今日の問題:ニセ医者騒ぎ” [Problem of the Day: The Fake Doctor Scandal]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Evening Edition, April 3: 2.

Asahi Shimbun. 1979. “天声人語” [Tensei jingo column (lit. Heavenly Voice of the People). Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Morning Edition, July 6: 1.

Asahi Shimbun. 2023. “県央基幹病院、3月開院:高齢化や医師不足に対応” [Kenō Core Hospital [Set To] Open [Next] March: A Measure [to Deal with] Population Aging and Doctor Shortages]. Asahi Shimbun. Niigata Morning Edition, December 27: 19.

Banshōya, Mitsuhara. 2013. “戦後の医療供給体制の整備動向に関する一考察”[The Postwar Organization of the Medical Healthcare Care System]. 四天王寺大学大学院研究論集 [Shitennōji University Graduate School Collection of Research Essays] 8: 131–55.

Bay, Alexander. 2012. Beriberi in Modern Japan: The Making of a National Disease. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Burns, Susan. 1997. “Contemplating Places: The Hospital as Modern Experience in Meiji Japan.” In New Directions in the Study of Meiji Japan, edited by Helen Hardacre and Adam Kern, 702–18. New York: Brill.

Dower, John. 2000. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Endō, Yoshinobu. 1994. 近代日本:軍隊教育史研究 [The Historical Research of Modern Japanese Military Education]. Tokyo: Aoki Shoten.

Fukunaga, Hajime. 2014. 日本病院史 [The History of Hospitals in Japan]. Tokyo: Pillar Press.

Ginzburg, Carlo. 1992 (orig. 1976). The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth Century Miller. Translated by John and Anne Tedeschi. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gordin, Michael. 2007. Five Days in August: How World War II Became a Nuclear War. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hayashi, Hirofumi. 2005. “Japanese Deserters and Prisoners of War in the Battle of Okinawa.” In Prisoners of War, Prisoners of Peace, edited by Barbara Hately-Broad and Bob Moore, 49–58. London: Berg Publishers.

Haraoka, Isamu. 2012. Interview by the Japan Veterans Video Archive Project. May 1.

Haraoka, Isamu. 2014. Interview by author. May 9.

[National Diet of Japan]. 1948. 医師法 [Medical Doctors’ Act]. Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare Website: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/web/t_doc?dataId=80001000

Harari, Reut. 2019. “Medicalised Battlefields: The Evolution of Military Medical Care and the ‘Medic’ in Japan.” Social History of Medicine 33(4): 1143–1166.

Harari, Reut. 2020. “Between Trust and Violence: Medical Encounters Under Japanese Military Occupation During the War in China (1937–1945).” Medical History 64(4): 494–515.

Hashimoto, Kōichi. 2008. 専門職養成の政策過程 : 戦後日本の医師数をめぐって [Policy Processes in Professional Training: The Number of Doctors in Post-War Japan]. Tokyo: Gakujutsu shuppankai.

Havens, Thomas. 1978. Valley of Darkness: The Japanese People and World War Two. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Howell, David. 2005. Geographies of Identity in Nineteenth-Century Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Iijima, Wataru. 2009. “Colonial Medicine and Malaria Eradication in Okinawa in the Twentieth Century: From the Colonial Model to the United States Model.” In Disease, Colonialism, and the State: Malaria in Modern East Asian History, edited by Ka-che Yip, 61–70.Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Ishihara, Akira. ed. 1967. 看護二十年史 [20 Years of Nursing History]. Tokyo: Medical Friend.

Ishikawa, Kōyō. 1992. 東京大空襲の全記録:グラフィック・レポート [The Complete Records of the Great Tokyo Air Raid: A Graphic Report]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Iwagaki, Masato. 2018. “アメリカ支配下での沖縄の統治構造と法制度” [The Governing Structure and Legal System of Okinawa Under American Rule]. 沖縄大学法経学部紀要 [Bulletin of Okinawa University Faculty of Law and Economics] 28: 1–23.

Jaundrill, Colin. 2016. Samurai to Soldier: Remaking Military Service in Nineteenth-Century Japan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

JFBA (Japan Federation of Bar Association). 2024. “日弁連の会員.” [JFBR Membership]. March 1. https://www.nichibenren.or.jp/jfba_info/membership/about.html.

Katō, Yōko. 1996. 徴兵制と近代日本 [Conscription and Modern Japan]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan.

Kawakami. Yuko. 2012. “国民健康保険組合の設立と保健婦活動の展開” [The Establishment of National Health Insurance and the Development of Public Health Nurse Activities]. 文化看護学会誌 [The Society of Cultural Nursing Studies Bulletin] 4, no. 1: 38–46.

Kerr, George. 2000 (orig. 1958). Okinawa: The History of an Island People. Tokyo: Tuttle.

Kim, Hoi-Eun. 2014. Doctors of Empire: Medical and Cultural Encounters Between Imperial Germany and Meiji Japan. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Kinjō, Kyomatsu. 1963. “琉球医学史概説” [Overview of Ryūkyū History of Medicine]. 東女医大誌 [The Tokyo Women’s Medical University Bulletin] 33, no. 11: 595–602.

Kumagai, Yoshiya. 1973. “ひと:日本学術会議会員に繰り上げ当選した—熊谷義也”[Hito column (lit. People): Kumagai Yoshiya, Runner-up Elected Member of the Science Council of Japan]. Asahi shimbun. Tokyo Morning Edition, November 1: 5.

Maeda, Yuki. “明治後期の沖縄における感染症流行と衛生” [The Spread of Infectious Diseases and Hygiene in Okinawa in the Late Meiji Period]. 島嶼地域科学 [Journal of Regional Science for Small Islands] 2(2021): 41–61.

Masubuchi, Asako. 2017. “Nursing the U.S. Occupation: Okinawan Public Health Nurses in U.S.-Occupied Okinawa.” In Rethinking Postwar Okinawa: Beyond American Occupation, edited by Pedro Iacobelli and Hiroko Matsuda, 21–38. London: Lexington Books.

Masubuchi, Asako. 2019. Life Under Siege: Militarized Welfare in U.S.-Occupied Okinawa. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Toronto.

Matsumoto, Masatoshi et al. 2010. “Retention of Physicians in Rural Japan: Concerted Efforts of the Government, Prefectures, Municipalities and Medical Schools.” Rural and Remote Health 10. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH1432.

Meguro, Akane. 2022. 近代「女医」の歴史社会学的研究:竹内茂代「女の健康運動」の萌芽 [A Socio-Historical Study of “Women Doctors” in the Modern era: the Origins of Takeuchi Shigeyo’s “Women Health Movement”]. Doctoral Dissertation, Tsukuba University.

Meyer, Stanislaw. 2020. “Between a Forgotten Colony and an Abandoned Prefecture: Okinawa’s Experience of Becoming Japanese in the Meiji and Taishō Eras.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 18(20). https://apjjf.org/2020/20/Meyer.html.

Miyazato, Zenshō and Tomiyama Mitsue. 2014. Interview by author. April 20.

Nada, Inada (Horiuchi Shigeru). 1972. “現代ニセ医者論:意味ない「資格」偏重” [The Current Fake Doctor Debate: Disproportionate Emphasis on Meaningless “Qualifications”]. Asahi Shimbun. Tokyo Evening Edition, February 9: 6.

Nakamura, Eri. 2018. 戦争とトラウマ:不可視化された日本兵の戦争神経症 [War and Trauma: How Japanese Soldiers Suffering from War Neurosis Were Made Invisible]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan.

Ogawa, Teizō. 1972. 日本の医学教育史 [The History of Medical Education in Japan]. 医学教育 [Medical Education] 3 (1): 6–9.