Abstract: Although there is a clear rise in academic interest in region formation, theoretical approaches to the topic vary greatly, stemming from geopolitical identifications of objective regional boundaries, through functionalist ideas of regional linkages, to post-structuralist ideas about fluid regional belonging. This article provides a typology of region formation approaches, based on the ontological assumptions of its authors. The typology is based on two main debates within contemporary international relations ontology: regarding the basic components of reality (material vs. ideational) and regarding the status of theories (transfactual vs. phenomenalist). The presented matrix provides an ideal-typical position for each of these four iterations and illustrates its viability in the case of region formation literature on the Asia-Pacific. Doing so, the text contributes to (meta)theoretical discussions of how regions are formed while at the same time illustrating the often-overlooked stories of region formation.

Keywords: Regionalism, ontology, metatheory, typology, region formation, Asia

Introduction

It is becoming increasingly clear that although we have witnessed several decades (or even centuries) of globalization, regions and regionalisms are more important than ever. A number of analysts have pointed this out. Barry Buzan (2012) noted that regions act as a “central feature” of international relations (IR) and a regional perspective “may tell us more about the current transformation of international society” than the study of superpowers. Amitav Acharya (2018) has argued that due to the gradual decline of American power in the world, research should revolve around “regional worlds” to better grasp the influence of regionalism in world politics. The rise of regionalism, as Borzel and Risse (2016) claim, has been clearly visible in the growing IR literature on the topic, signified by the works of Katzenstein (2005), Lake and Morgan (1997), Solingen (1998), Söderbaum and Shaw (2003), Acharya (2007, 2009), van Langenhove (2011), Wunderlich (2016), Spandler (2018), Bilgin and Futák-Campbell (2021), Prys-Hansen, Burilkov, and Kolmaš (2023), Prys-Hansen and Frazier (2024), and others.

Despite this enhanced attention to regionalism and region formation, however, the literature has not come to a consensus on how regions are created and maintained. Indeed, especially due to the rising complexity of IR thought through efforts at its decolonization and multiculturalization (Blaney and Tickner 2017, Brunner 2021), it is understandable that there will be varied interpretations of region construction and consolidation. Ranging from geopolitical and realist thought highlighting the role of objective boundaries and power projections (Gilpin 1987, Hurrell 2005), through the liberalism-derived theories of European integration such as (neo)functionalism and federalism that highlight the finer processes of integration (Mitrany 1966, Rosamond 2000, Hettne and Söderbaum 2008), institutional and regime theories focusing on changes in state preferences (Mansfield and Milner 1997), to constructivist accounts of regional security complexes and communities (Buzan and Waever 2003) and post-structural visions of regional fluidity (Jessop 2003), a plethora of authors have provided us with a palette of worldviews on the topic.

While these may be converging as some authors have claimed (Soderbergh 2011 has, for instance, argued that most scholars engaged in the contemporary debate agree that there are no natural or ‘scientific’ regions, and that those definitions of a region vary according to the particular problem or question under investigation), the range of problems and questions that analysts use to undertake their research of regionalism remains significantly wide, leading to increasingly broad identifications of regions and their composition.

For example, focusing on political economy and the flows of material goods would likely identify different regions than focusing on shared history and cultural links. But the divisions run deeper than a simple distinction between issue areas around which regions are formed. The divisions go directly into the ontological assumptions regarding the discipline that the authors hold. For many of the rationalist thinkers, regions remain definable by objective criteria such as trade flows and spheres of influence. For the more constructivist and critical authors, regions are mere political or discursive creations without any reference to objective reality (Zarakol 2022, van Langenhove 2011, Neumann 2003). While this debate might seem purely academic, as many post-structuralist authors have already pointed out, the way we see (and narrate) the world has deep consequences for the shape it turns out to be (Neumann 2009).

In other words, the way we speak about regions has a direct influence on how they shape up politically. Moreover, the distinct identification of regions reaches far beyond the focused regionalism literature. The ontological and epistemic roots are visible in all parts of international relations that in any way touch on the existence of regions. Speaking about the European Union as a group of states, contrary to speaking about it as a singular entity, presupposes distinct assumptions about the role of actors in international relations. Understanding the varieties of these assumptions is thus essential for navigating our way through the distinct discipline that IR is (Wight 2006).

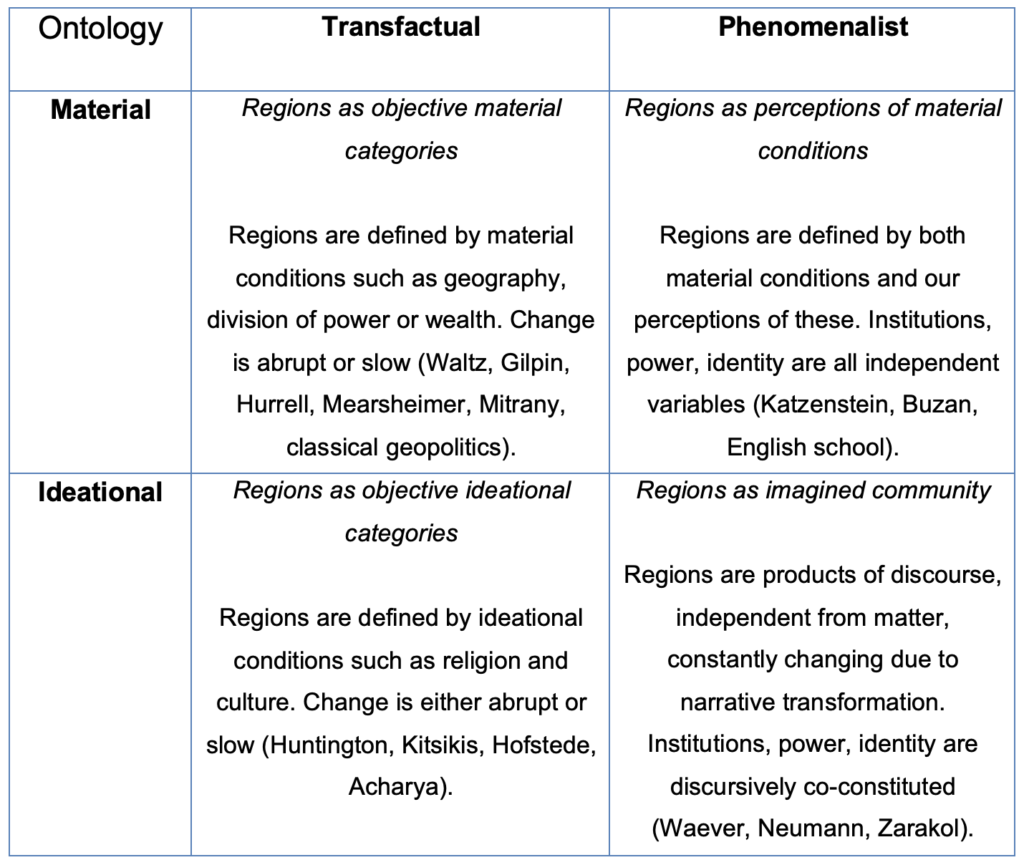

It is the aim of this article to review the theoretical foundations of region formation and consolidation and attribute them to an original ideal type matrix based on differing ontological positions of their authors. In line with the contemporary interest of IR ontology scholarship (Jackson 2011, Lake 2011), the typology is based in the distinction of material vs. ideational and transfactual vs. phenomenalist approaches. This metatheoretical typology aims to provide a complex, yet comprehensible, illustration of different modes of understanding regional dynamics. In particular, it allows us to 1) make sense of the varied ideas about what regions constitute the world that certain agents hold and 2) illustrate that there are various ideas of region formation, that are ultimately linked to inherent objectives of actors that pursue them. While the aims of the article are purely (meta)theoretical, the typology thus can help us navigate both theoretical and empirical dynamics of region transformation that are happening in the world right now, while at the same time allowing us to identify and bring to light the marginalized narratives of region formation.

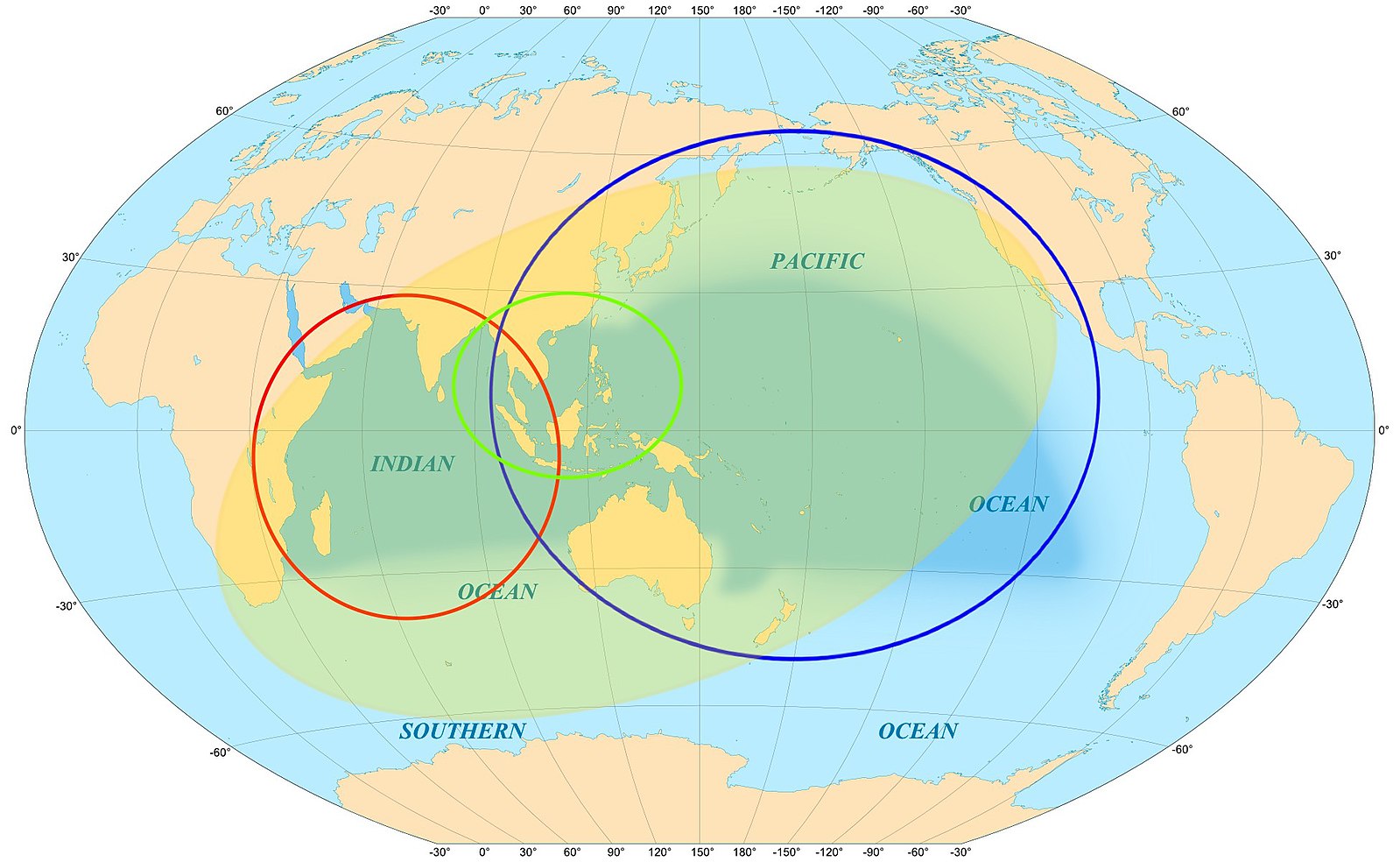

After presenting the ideal types of ontologies of region construction, this article tests the typology on the contending interpretations of region formation in the Asia-Pacific by categorizing the dominant visions for regional orders in Asia according to the authors’ ontological assumptions. I have chosen the Asia-Pacific for three particular reasons. First, Asian regions are utmost political constructs derived from centuries of great power incursions (see Zarakol 2022). Second, for large parts of the post-WW2 history, general IR theories have been used to identify and solidify regional orders in Asia, further stripping Asian countries of their agency (Hemmer and Katzenstein 2002). Third, there has been a recent discussion in theory and practice of IR that has attempted to redefine the region as “Indo-Pacific” (Kolmaš, Qiao-Franco and Karmazin, 2024). While it is not the aim of this paper to revisit this discussion, this shows that regional demarcations in Asia are flexible and prone to change even to this day.

Presenting the Typology

Ontology is the study of the essence of being. In the discipline of international relations, ontology has been increasingly defined in contemporary literature by two broad questions: what is the essence of reality (who are the actors –individuals? structure? ideas? practices? matter?) and what is the status of theories – are they transfactual, meaning that they are based on the real experiences of structures that generate observable things that we may then study, or are they phenomenalist, meaning that they are based on the scholar’s experiences and not rooted in any further claim about something really existing outside of those experiences (Jackson 2011, Lake 2011 and 2013)?

The first debate has been heavily represented in the so-called fourth great debate in IR theory, that was waged between the positivists and the reflectivists in the 1980s and 1990s. It focuses on several questions regarding the essential components on which the reality of international relations is built (Wendt 1987). Initially, the debate revolved around the famous agent/structure divide, in which agent-based realist and liberal theories became increasingly criticized by their neo-variants as well as many of the post-positivist theories (post-structuralism, postmodernism, feminism) that argued that the theory and practice of IR rests on structural assumptions, and that state policies only can be explained with regard to international systems (be it the systems of power distribution or the systems of meaning-making). While this discussion is sometimes still reflected in the IR debates, since the constructivist incursion linking agents to structures into hermeneutic circles, it has become increasingly clear that neither of these ideal points fully represented the political realities of the discipline. Trownsell has recently made this point clear (2022: 801), by arguing that the idea that global politics are constituted through actors beyond the human, which was largely introduced into the field by social constructivism, is now evident in the field and has been increasingly prominent with the rise of disciplinary globalization.

Yet while we increasingly acknowledge the co-constitution of social reality by agents and structures, the question of whether these constitutive structures for the practice of IR are ideational or material remains alive and well to this day. The theoretical distinction between rationalist paradigms such as realism, liberalism, and their neo-variants—Marxism and others that understand the world to be underlined by material assumptions (such as history, economics, or the simple amount of weapons)—and ideationalist ones that see ideational structures (perceptions, identities, norms and the like) as key to our understanding of the world continues to be heavily represented in contemporary IR literature (see Knio 2022, Castro Moreira 2021).

It is by no means the aim of this article to go into the details of these debates beyond the few paragraphs above, but they are presented to provide the rationale for why the material-ideational distinction comprises the first component of the presented typology. Material ontology entails theories and authors that usually understand essential, tangible and relatively unchangeable factors as decisive in region formation. These may mean apparent existing geographical boundaries such as mountain ranges that separate regions, power spheres and zones of influence as well as measurable economic ties between particular countries. For many, these have formed a “substance” of region formation that has had an indispensable role in the consolidation of regional frameworks (Buzan, Weaver and de Wilde 1997, Hemmer and Katzenstein 2002, Buzan and Zhang 2014, Kolmaš, Qiao-Franco and Karmazin 2023).

Ideational ontology, on the other side of the spectrum, resides in the idea that all attributes of the system, even though physically apparent, only make sense when perceived by cognitive agents. Social norms and identities define the way in which material is perceived. Rivers can be perceived as boundaries, but also as veins of social ecosystems around which civilizations emerge. Mostly linked with the varieties of social constructivism and post-positivist theories, ideational approaches are interested in regional belonging, identification, and narratives that, according to them, define the place of actors in reality (Waever 2000, Tickner 2013). Contrary to the materialist assumptions defined above, ideational ontology does not speak in terms of substances, and assumes change, rather than continuity, to be the defining factor of regional belonging. This material-ideational distinction will provide the first two ideal points in the presented typology.

The second great discussion in contemporary ontology, according to Jackson (2011), revolves around the status of each particular theoretical approach. The transfactual vs. phenomenalist distinction in many ways copies the positivist vs. reflectivist/post-positivist debate on the discipline’s epistemology and discusses the possibility of objective (essentialist) causality in social sciences. Transfactual theories/approaches (most of the positivist ones) argue that there is observable knowledge generated outside of the researcher’s perceptions. Since this knowledge/reality is objective, it can be studied similarly to how the natural sciences approach real world phenomena. These approaches have generated generalizable assumptions and hypotheses and have tested them to produce replicable scientific outcomes (i.e., democratic peace theory). Phenomenalist approaches (most reflectivist theories), on the other hand, reject any possibility of causality in social reality and argue that there is no objective, outside knowledge that can be discovered. They have thus focused on constitutive relationships and tried to understand, rather than explain, social events in their unique circumstances.

Linking this debate to region formation, the question is whether there are objective, largely unchanging characteristics of regions, or whether regional boundaries are fluid and prone to change with the change of social circumstances (usually in the form of dominant narratives). The former has been heavily linked with traditional geopolitical studies of region formation, especially those of the Anglo-Saxon geopolitical school (Halford Mackinder, Nicholas Spykman, Alfred Mahan, and others) and their followers. That said, a significant part of more up-to-date approaches, building on realism, liberalism, and other positivist theories (Mitrany, Waltz, Gilpin, Mearsheimer, etc.), have continued in this tradition, albeit in different terms—focusing on measurable, tangible factors such as power distribution and spheres of influence, but increasingly also applying these approaches to intangible assets such as national and strategic cultures. For transfactualists, regions are usually essential, that is, defined by unchanging characteristics. If change happens, it may be due to structural shocks such as wars or a new division of power (Widmaier, Blyth, and Seabrook 2007), or slow onset developments like profound cultural change (Widmaier and Park 2012).

Contrary to transfactualism, phenomenalist approaches stress the impossibility to separate theory and practice, as well as the theorist and the theory. This strand of literature on region formation has revolved around the notion that various modes of regional demarcation are inextricably linked to the positionality of the observers and their perceptions vis-a-vis the regional space. Usually relying on reflectivist epistemology, these studies have highlighted the role of identity, storytelling, and other ideational factors and processes in fostering regions and posited that there are many ways in which regions, states, and communities in general exist. The same community may be understood differently when seen from within and from outside, and the self/other distinction plays a large role in this identification. That said, there is no consensus on whether the relationship between identity and region formation is exclusive or inclusive, that is, whether identity is just one among several factors (including material ones such as wealth-seeking or power assumptions, see Berenskoetter 2010, Guillaume 2011, Kolmaš 2020) that influence region consolidation, or whether a region only exists in the imageries of actors and not outside of it. The Copenhagen school of constructivism (i.e., Buzan 2012) has pioneered the former, while the recent post-structural literature has offered explanations in line with the latter (Neumann 1998, Hagstrom and Gustafsson 2015). The division between transfactual and phenomenalist approaches forms the second pair of ideal types for the presented typology.

Linking the materialist-idealist and transfactual-phenomenalist ontological assumptions creates four distinct ideal positions linking the two great ontology debates in IR. These are indeed ideal types, meaning they do not necessarily have to be represented fully in reality (IR research). They should be understood as two axes, along which actual IR research revolves. In the top-left quadrant, transfactual and material positions link to illustrate a position of regions as objective material denominations. Building on rationalist material theories, this position assumes that regions exist outside of the observers’ perceptions and are easily distinguishable based on their existing preconditions. They are defined by their material conditions such as mountain ranges, river flows, but also on tangible yet political conditions such as power distribution and economic interdependence.

The bottom-left ideal position in the typology refers to transfactual and ideational assumptions of region formation. This position assumes that regions are created and maintained by relatively unchangeable, yet ideational (rather than material) conditions such as shared cultures and religions. Culture of states is understood in essentialist terms, according to prevailing and measurable patterns of behavior and institutions rather than by intangible features such as the perceptions of self and other. Samuel Huntington’s seminal piece the Clash of Civilizations (1996), which divided regions based on their cultural characteristics, is perhaps the clearest example of this ideal point, but Geert Hofstede’s (1998) typology of national cultures falls within the same category. One could perhaps argue that even Amitav Acharya’s groundbreaking work on region formation in Southeast Asia places culturally-derived social norms on top of the pyramid of region forming factors, although arguably it is distinct from the more essentialist views of Huntington and Hofstede. Similarly to material-transfactual positions, only limited change is envisioned for regions formed in this way, as according to these authors changing cultures and religions is a slow and uncertain process. Both culture and religion are assumed to be distinct and exclusively shared by the whole civilizational/regional structures, and therefore they create borders and exclude those that do not belong to them.

The top-right position links phenomenalist and material ontological assumptions. While speaking in terms such as identity, memory, and belonging, and understanding the connections between such intangible concepts and state policies (as well as individual and collective perceptions), these approaches give greater agency to culture and advocate for greater flexibility in these concepts compared to the transfactual/ideational position. That said, they understand ideational concepts as an addition to existing material realities rather than categories on their own. The Constructivist school of Japan’s foreign policy (Katzenstein and Okawara 1993; Berger 1998) has for instance argued that Japan’s post-war pacifist Constitution has instilled antimilitarist norms into Japanese foreign policymaking. Yet these norms by themselves cannot fully explain Japan’s behavior and need to be understood in a broader set of Japan’s positioning in the international system. Linking this theoretical position to region formation, while perceptions are important in this constitutive process, they form another set of independent variables that help to explain why certain regions emerge and others do not. In many ways, however, these approaches share some central assumptions with positivist-material theories, such as the primacy of anarchy in world politics and the important role of tangible factors. Conventional constructivism (as pioneered by Wendt, Katzenstein, Berger, and others) is the prime example of this ideal position.

Finally, the bottom-right position denotes the combination of phenomenalist and ideational ontological positions. The most radical of the four, this position entails post-structural and other reflectivist works that understand regions to be inherently flexible and constantly changing. The positionality of the agents is central to their assumptions of regional change, and regions may emerge or cease to exist as soon as social conditions conducive to their formation alter. Whether a country belongs to, for instance, Western or Eastern Europe does not depend on its geographical placing or shared culture, but on the prevailing hegemonic narrative of that time. Othering acts as the most frequent process of regional demarcation, and all regions are understood to be political rather than objective creations. See the typology below.

Figure 1: Typology of region formation ontologies

The Typology of Region Formation Ontology and the Asia-Pacific

Having identified the most prominent types of region formation literature, the paper now turns to demonstrate its applicability on the various literatures of regional demarcation in the broader Asia-Pacific region. The demarcations of Asian macroregions are complex and constantly evolving, depending on the political will, norms diffusion and power distribution over the broad area. I have chosen the regional term “Asia-Pacific,” because, contrary to other possible ways of addressing the region (ie. East Asia, Southeast Asia, Indo-Pacific), it is a relatively coherent category, that, albeit being socially constructed, encompasses most of the relevant actors, including all East and Southeast Asian states, but also the United States, Australia and New Zealand, that are inseparable from the evolution of regional political and economic systems (see He and Feng 2020). Furthermore, contrary to the trending conception of the Indo-Pacific, the Asia-Pacific is significantly more institutionalized in both political and economic ties, and therefore actually functions as a region rather than a geopolitical imagination (Kolmaš, Qiao-Franco and Karmazin 2024).

Over the course of the last several decades, the Asia-Pacific has emerged as perhaps the most intriguing region for IR analysts. Undergoing dramatic changes in terms of economic development, political institutions, and regional security dynamics, many theorists have tried to analyze the evolving boundaries of the region. And yet, the story of Asia-Pacific regionalism is quite complicated. During the Cold War, there was virtual nonexistence of regional cooperation due to several interrelated factors including divided spheres of influence between the two major superpowers, the legacy of Japanese imperialism, and the lack of leadership among Asian powers (Dieter 2007, He and Inoguchi 2011, Beeson 2014, He and Feng 2020).

In the 1990s, things began to change. The gradual incorporation of China into the world economic and political system, together with the disappearance of structural boundaries after the dissolution of the Soviet bloc, and a growing willingness of many parties in Asia to lead regional integration, led clearer regional demarcations to emerge. The Organization of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) consolidated the political creation of Southeast Asia and established several institutions on ASEAN’s blueprint, including the East Asian Summit, ASEAN Regional Forum, and ASEAN+ platform (Dent 2016). Elsewhere, Japan, Australia, and the United States pursued the establishment of regional economic cooperation in Asia-Pacific Economic Community (APEC) that has significantly helped to reduce trade barriers over the largely defined region, but has also had a vital role in the consolidation of the Asia-Pacific.

Recently, the new Indo-Pacific narrative has become widely shared among policymakers and IR theorists. Kickstarted by the late Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe’s idea of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific, the new regional demarcation was soon picked up by the former U.S. president Donald Trump, who inserted the term into American security strategy. Many others, including many European states (together with the European Union), have produced their own Indo-Pacific strategies, replicating the discourse set by Abe. Several regional institutions were formed on the Indo-Pacific basis, including the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and the Australia-United Kingdom-United States security cooperation (AUKUS, see Koga 2020). While the Indo-Pacific was readily applauded by many of the “allied” powers of the U.S.-led security community, many others have trouble accepting this new political construct. China understood the region as an attempt to curb its rise and ASEAN became worried about losing its central position in achieving regional cooperation and security.

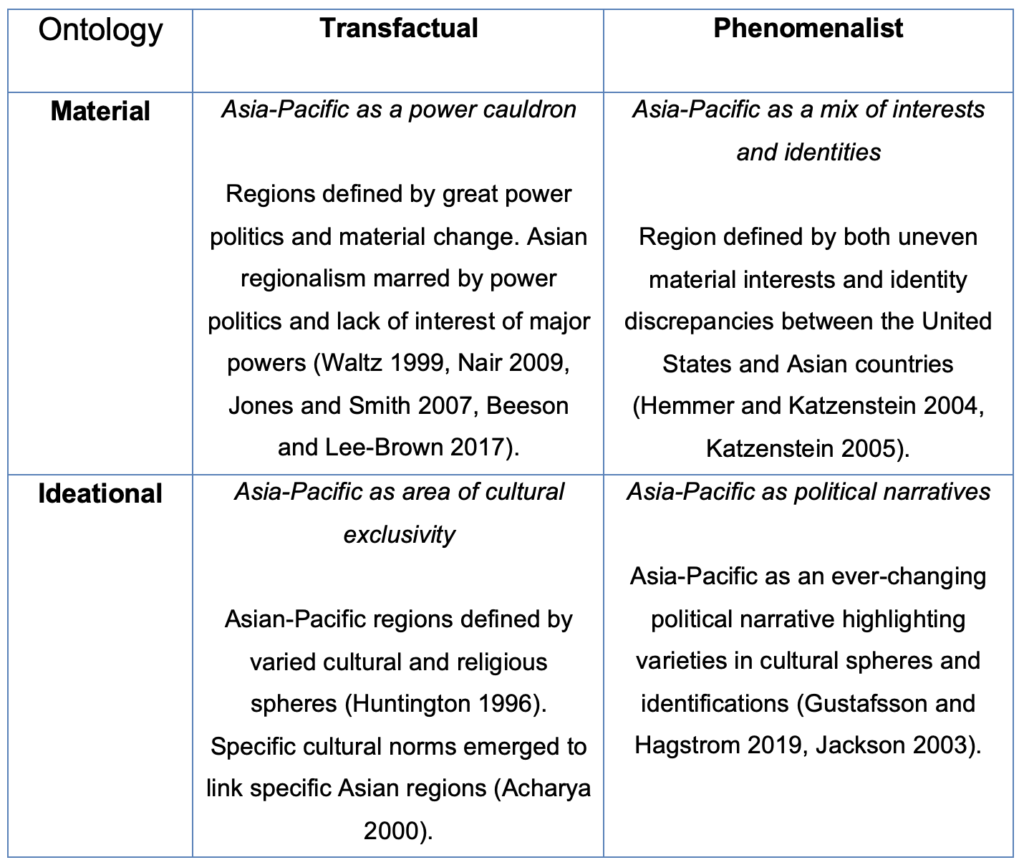

The most relevant and widely cited analysts and IR scholars have provided us with various stories of Asia-Pacific regional formation. The top-left quadrant (transfactual – material type) has identified regions in the Asia-Pacific according to prevailing essential qualities often linked to power interests of major powers. The lack of region-building multilateralism during the Cold War was understood to be a product of the U.S.-preferred bilateralist strategy that sedimented into a “hub and spoke” system. Superpower confrontation, especially between the U.S., China, and Russia, prevented the consolidation of broader regions in the Asia-Pacific. Only with the disappearance of the structural obstacles with the end of the Cold War did circumstances began to change, leading to a slow onset of regional groupings due to the pressures of balance of power politics (see Waltz 1982 and 1999, Nair 2009, Jones and Smith 2007, Mearsheimer 2010). That said, regionalism remains shallow or limited to the economic sphere.

The bottom-left ideal type, linking transfactual and ideational ontological positions, shares the assumptions that regional formation and change is slow or conducted by structural shifts, and that there are tangible factors that constitute these changes. Contrary to the top-left position, however, ideationalists believe that it is not necessarily the distribution of material resources which defines region formation. Rather, it is the underlying cultural assumptions linked to particular societies, on which power politics are formed. These can be either simply culturally essentialist, defining divisions between exclusive cultures that lead to differences in policy preferences (Huntington 1996, Hofstede 1998), or based on social sources of national identities such as shared yet often exclusive norms of conduct (Acharya 2000, 2018). Both of these—although in highly diversified ways—argue that regions in Asia were built on the basis of shared cultures and cultural norms that were defined within their particular territories. Acharya and Stubbs (2006, and many others) focus on the norms of ASEAN as region-building factors, while Huntington (1996) defines particular regions in Asia based on their religious roots, such as the Sinic one.

The top-right position, linking phenomenalist and material ontological assumptions, accepts many propositions of the material-transfactual position, such as primacy of power politics and anarchy in the international system. That said, it shows that there are other possible factors that constitute these essentialist components. Identity is seen as an especially important one. In their seminal piece, Hemmer and Katzenstein (2002) asked why there is no NATO—or a broader security community—in Asia like that which emerged in Europe. They argued that the U.S. racial prejudices of Asia of that time heavily contributed to Washington’s decision not to pursue a multilateral security arrangement in Asia similar to the one in Europe. Further studies have highlighted the role of historical memory in Asian region formation, which has arguably limited the possibility of regional institutionalization following World War 2 (Hasegawa and Togo 2008, Shin and Schneider 2010).

Lastly, the bottom-right position, linking phenomenalist and ideational ontological assumptions, provides a completely distinct story of Asian regionalism. Highlighting the constitutive elements of discourses and narratives, these theorists do not share the primacy of power settings as tools of region formation, and instead highlight political narratives, storytelling, myths, and identifications, which define how material power is perceived and applied. While there are some sedimented narratives (often called master narratives, see Hagstrom and Gustafsson 2019, Kolmaš 2022), such as the realist version of the rise of China, there are a plethora of counter-narratives that provide for an alternative reading of history. Building on the practice of othering, they show that regions as well as state identities were formed in the process of differentiation vis-a-vis various others, whether it be the West (Suzuki 2015, Spivak 2004), backwards Asia (Tamaki 2015), their own temporal pasts (Hanssen 2019), or others. Post-structuralists also highlight the variations within and between these regions, which are often overlooked by essentialists (Jackson 2003, Curaming 2006). Because of these (rather than by structural shifts), regions are inherently unstable and continuously changing, and any attempt to define them in essentialist terms is inevitably irrelevant.

Figure 2: Typology of Asian region formation ontologies

Conclusion

Various ontological positions provide us with completely distinct stories of regional formation. Understanding—and acknowledging—that these positions exist allows us to better understand the varieties of ways in which agents define world politics. This article has put forward the argument that there are four distinct types of region formation ontologies according to the transfactual-phenomenalist debate regarding the status of theories and their epistemological assumptions, and the material-ideational debate regarding the main building blocks of (social) reality.

How will this typology help us, and what does it contribute to existing debates on region formation? We believe that it does so in at least two interlinked ways. First, it allows us to make sense of the varied ideas about what regions constitute the world. Visible in the several distinct ways in which the Asia-Pacific is defined, ontological positions condition authors into presenting regional demarcations that might be easily contradictory to others’ views. The use of specific terms such as East Asia, Asia-Pacific, Indo-Pacific and the like, does not mean that these are objective categories according to which the region is defined. Instead, these terms are reflections of the motivations (be it instrumental, or subconscious – derived from a certain discursive framing) of the actors that use them. Acknowledging this allows us to problematize the terminology that we make use of to explain world politics.

Second, the typology allows us to emancipate marginalized stories of region formation. Indeed, some of the region narratives are more dominant than others. For instance, over the last several years, the Indo-Pacific has emerged as perhaps the most frequent concept connected to Asian regional politics (see, i.e., He and Fang 2020). Other regional demarcations, including the Asia-Pacific, East Asia, and Southeast Asia have thus become significantly less represented in both official and unofficial discourses. Therefore, many actors that would prefer to use these alternative regional demarcations have found it increasingly difficult to do so. Even ASEAN, a pioneer of Southeast Asian, but also East Asian regionalism, has eventually came up with an Indo-Pacific strategy. But illustrating the motivations that lead agents to propose these narratives also illustrates that this is just one among many positions that exist in both the theoretical literature and empirical politics.

This is especially important if we agree with the reflectivist assumptions that world politics are hidden within stories people say to make sense of reality. Speaking of the Asia-Pacific as a cauldron of power politics or a hub of future integration thus has a profound effect on practical policymaking. Understanding that this is so is the first step towards a much-needed reflection on the constitutive aspect of the discipline of international relations.

Acknowledgements: The article is the outcome of the Metropolitan University Prague’s research project no. 100-4 ‘C4SS’ (2024) based on a grant from the Institutional Fund for the Long-term Strategic Development of Research Organizations.

References

Acharya, A. and A. I. Johnston. 2007. Crafting Cooperation: Regional Institutions in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acharya, A. and R. Stubbs. 2006. “Theorizing Southeast Asian Relations: An Introduction.” The Pacific Review 19(2): 125–134.

Acharya, A. 2000. Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia: ASEAN and the Problem of Regional Order. London: Routledge.

Acharya, A. 2009. Whose Ideas Matter? Agency and Power in Asian Regionalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Acharya, A. 2018. The End of American World Order, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Beeson, M, and T. Lee-Brown. 2017. “The Future of Asian Regionalism: Not What It Used to Be?” Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 4: 195–206.

Beeson, M. 2014. Regionalism and Globalization in East Asia. London: Springer.

Berger, T. U. 1998. Cultures of Antimilitarism. National Security in Germany and Japan. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Berenskoetter, F. 2010. “Identity in International Relations,” in The International Studies Encyclopedia Vol. VI, eds. Robert A. Denemark and Renée Marlin-Bennett, 3595–3611. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bilgin, P. and B. Futák-Campbell. 2021. “Introduction: Globalizing (the Study of) Regionalism in International Relations,” in Globalizing Regionalisms and International Relations, ed. Beatrix Futák-Campbell, 3–27. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Blaney, D. L., and A. B. Tickner. 2017. “Worlding, Ontological Politics and the Possibility of a Decolonial IR.” Millennium 45(3): 293–311.

Borzel, T. A. and T. Risse. 2016. The Oxford Handbook of Regionalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brunner, C. 2021. “Conceptualizing epistemic violence: an interdisciplinary assemblage for IR.” International Politics Reviews 9: 193–212.

Buzan, B. and Y. Zhang. 2014. Contesting International Society in East Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buzan, B. and O. Wæver. 2003. Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buzan, B, O. Wæver and J. De Wilde. 1997. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Buzan, B. 2012 “How regions were made, and the legacies for world politics: an English School reconnaissance”, In International Relations Theory and Regional Transformation, eds. by T.V. Paul, 22-46. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Curaming, R. A. 2006. “Towards a Poststructuralist Southeast Asian Studies?” Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 21(1): 90–112.

Dent, C. M. 2016. East Asian Regionalism. London: Routledge.

Dieter, H. 2007. The Evolution of Regionalism in Asia. London: Routledge.

Gilpin, R. 1987. The Political Economy of International Relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Guillaume, X. 2011. International Relations and Identity: A Dialogical Approach. London: Routledge.

Hagstrom L. and K. Gustafsson. 2015. “Japan and Identity Change: Why It Matters in International Relations.” The Pacific Review 28(1): 1–22.

Hagström, L. and K. Gustafsson. 2019. “Narrative Power: How Storytelling Shapes East Asian International Politics.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 32(4): 387–406.

Hasegawa, T. and K. Togo. 2008. East Asia’s Haunted Present. Westport: Greenwood Publishing.

He, B. and T. Inoguchi. 2011. “Introduction to Ideas of Asian Regionalism.” Japanese Journal of Political Science 12(2): 165–177.

Hemmer, C. and P. J. Katzenstein. 2002. “Why is There No NATO in Asia? Collective Identity, Regionalism, and the Origins of Multilateralism.” International Organization 56(3): 575–607.

Hettne, B. and F. Söderbaum. 2008. “The Future of Regionalism: Old Divides, New Frontiers,” in Regionalization and the Taming of Globalization, eds. Andrew F. Cooper, Christopher W. Hughes, and Philippe De Lombaerde, 97–128. London: Routledge.

Hofstede, G. 1998. Masculinity and Femininity: The Taboo Dimension of National Cultures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Huntington, S. P. 1996. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York, Simon & Schuster.

Hurrell, A. 2005. “The Regional Dimension in International Relations Theory,” in Global Politics of Regionalism: Theory and Practice, eds. Mary Farrell, Björn Hettne, and Luk Van Langenhove, 38–53. London: Pluto Press.

Jackson, P. Thaddeus. 2011. The Conduct of Inquiry in International Relations Philosophy of Science and its Implications for the Study of World Politics. London: Routledge.

Jackson, P. A. 2003. “Mapping Poststructuralism’s Borders: The Case for Poststructuralist Area Studies.” Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 18(1): 42–88.

Jessop, B. 2003. “The Political Economy of Scale and the Construction of Cross-Border Regions,” in Theories of New Regionalism. A Palgrave Reader, eds. Fredrik Söderbaum and Tim M. Shaw, 179–197. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jones, D. M. and M. L. R. Smith. 2007. “Constructing Communities: The Curious Case of East Asian Regionalism.” Review of International Studies 33(1): 165–186.

He, K. and H. Feng. 2020. “The Institutionalization of the Indo-Pacific: Problems and Prospects.” International Affairs 96(1): 149–168.

Katzenstein, P. J. and N. Okawara. 1993. “Japan’s National Security: Structures, Norms, and Policies.” International Security 17(4): 84–118.

Katzenstein, P. J. 2005. A World of Regions: Asia and Europe in the American Imperium. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Knio, K. 2023. “Why and How Ontology Matters: A Cartography of Neoliberalism(s) and Neoliberalization(s).” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 53(2): 160–182.

Koga, K. 2020. “Japan’s ‘Indo-Pacific’ Question: Countering China or Shaping a New Regional Order?” International Affairs 96(1): 49–73.

Kolmaš, M. 2020. “Identity Change and Societal Pressures in Japan: The Constraints on Abe Shinzo’s Educational and Constitutional Reform.” The Pacific Review 33(2): 185–215.

Kolmaš, M. 2022. “Why is Japan shamed for whaling more than Norway? International Society and its barbaric others.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, 22(2): 267–296.

Kolmaš, M., G. Qiao-Franco and A. Karmazin. 2024. “Understanding Region Formation Through Proximity, Interests, and Identity: Debunking the Indo-Pacific as a Viable Regional Demarcation.” The Pacific Review (online first), 1–23.

Lake, D. A. 2011. “Why ‘isms’ Are Evil: Theory, Epistemology, and Academic Sects as Impediments to Understanding and Progress.” International Studies Quarterly 55(2): 465–480.

Lake, D. A. 2013. “Theory is Dead, Long Live Theory: The End of the Great Debates and the Rise of Eclecticism in International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 19(3): 567–587.

Lake, D. A. and P. P. Morgan. 1997. Regional Orders: Building Security in a New World. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press.

Mansfield, E. D. and H. V. Milner. 1997. The Political Economy of Regionalism. New York: Colombia University Press.

Mearsheimer, J. J. 2010. “The Gathering Storm: China’s Challenge to US Power in Asia.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 3(4): 381–396

Mitrany, D. 1966. A Working Peace System. Chicago: Quardrangle Books (first ed. 1946).

Moreira, A. C. 2021. “IR Theory and The Ontological Depth of the Material-Ideational Debate”, e-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2021/05/31/ir-theory-and-the-ontological-depth-of-the-material-ideational-debate/. Accessed March 13, 2024.

Nair, D. 2009. “Regionalism in the Asia Pacific/East Asia: A Frustrated Regionalism?” Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs 31(1): 110–142.

Neumann, I. B. 1998. Uses of the Other: The “East” in European Identity Formation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Neumann, I. B. 2003. “The Region-building Approach,” in Theories of New Regionalism. A Palgrave Reader, eds. Fredrik Söderbaum and Tim M. Shaw, 160–179. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Neumann, I. B. 2009. “Returning Practice to the Linguistic Turn: The Case of Diplomacy,” in Pragmatism in International Relations, eds. Harry Bauer and Elisabetta Brighi, 98–116. London: Routledge.

Prys-Hansen, M, A. Burilkov and M. Kolmaš. 2023. “Regional Powers and the Politics of Scale.” International Politics 61(1): 13–39.

Prys-Hansen, M. and D. Frazier. 2024. “The Regional Powers Research Program: A New Way Forward.” International Politics 61(1): 1–12.

Rosamond, B. 2000. Theories of European Integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Shin, G-W. and D. C. Schneider. 2010. History Textbooks and the Wars in Asia. London: Routledge.

Soderbaum, F. 2011. “Theories of Regionalism,” in The Routledge Handbook of Asian Regionalism, eds. Beeson Mark and Richard Stubbs, 11–21. London: Routledge.

Söderbaum, F. and T. M. Shaw. 2003. Theories of New Regionalism: A Palgrave Reader. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Solingen, E. 1998. Regional Order at Century’s Dawn: Global and Domestic Influences and Grand Strategy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Spandler, K. 2018. Regional Organizations in International Society: ASEAN, the EU and the Politics of Normative Arguing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Spivak, G. C. 2004. “Poststructuralism, Marginality, Postcoloniality and Value,” in Postcolonialism, ed. Diana Brydon. 21-38, London: Routledge.

Suzuki, S. 2015. “The Rise of the Chinese ‘Other’ in Japan’s Construction of Identity: Is China a Focal Point of Japanese Nationalism?” The Pacific Review 28(1): 95–116.

Tamaki, T. 2015. “The Persistence of Reified Asia as Reality in Japanese Foreign Policy Narratives.” The Pacific Review 28(1): 23–45.

Tickner, A. B. 2013. “Core, Periphery and (neo)Imperialist International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 19(3): 627-646.

Trownsell, T. 2022. “Recrafting Ontology.” Review of International Studies 48(5): 801–820.

van Langenhove, L. 2011. Building Regions: Regionalization of World Order. Ashgate: Aldershot.

Wæver, O. 2006. “The EU as a Security Actor: Reflections From a Pessimistic Constructivist on Post-sovereign Security Orders,” in International Relations Theory and the Politics of European Integration, eds, Morten Kelstrup and Michael Williams, 250–294. London: Routledge.

Waltz, K. N. 1982. “The Central Balance and Security in Northeast Asia.” Asian Perspective 6(1): 88–107.

Waltz, K. N. 1999. “Globalization and Governance.” PS: Political Science 32(4): 693–700.

Wendt, A. E. 1987. “The Agent-Structure Problem in International Relations Theory.” International Organization 41(3): 335–370.

Widmaier, W. W. and S. Park. 2012. “Differences Beyond Theory: Structural, Strategic, and Sentimental Approaches to Normative Change.” International Studies Perspectives 13(2): 123–134.

Widmaier, W. W., M. Blyth and L. Seabrooke. 2007. “Exogenous Shocks or Endogenous Constructions? The Meanings of Wars and Crises.” International Studies Quarterly 51(4): 747–759.

Wight, C. 2006. Agents, Structures and International Relations Politics as Ontology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wunderlich, J-U. 2016. Regionalism, Globalisation and International Order. Europe and Southeast Asia, London: Routledge.

Zarakol, A. 2022. Before the West. The Rise and Fall of Eastern World Orders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.