Abstract: For almost 150 years, the Yūshūkan military museum on the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine has been one of the most prominent tourist sites in Tokyo. Opened in 1882 as Japan’s first Western-style museum, the Yūshūkan is often seen as the emblem of the so-called “Yasukuni view of history,” which downplays Japanese militarism and imperialism and is at the heart of tensions with other nations. This study is the first dedicated treatment of the long history of the Yūshūkan from its conceptualization in the 1870s to its place in Japan and the world in the 2020s. It argues that the origins of the Yūshūkan should be seen in the context of the global spread of the military museum as an institution in the late nineteenth century. Over the past 140 years, the Yūshūkan has gone from appealing to an emerging global standard to claiming a Japanese uniqueness as justification for its existence and has always been closely intertwined with global discourses on war, commemoration, and Japan’s place in the world.

Keywords: Yasukuni (Shrine), Yushukan, (Military) Museum, Memory, Meiji (Period)

For almost 150 years, the Yūshūkan military museum has been one of the most prominent tourist sites in Tokyo. The museum is on the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine, the main site for the veneration of Japan’s war dead, located atop Kudan Hill just to the north of the Imperial Palace. Opened in 1882, the Yūshūkan is Japan’s oldest Western-style museum, welcoming its first visitors several weeks before the Imperial Museum in Ueno (now the Tokyo National Museum). By the early twentieth century, the Yūshūkan often had more annual visitors than any other attraction in Tokyo—and therefore Japan—aside from the Imperial Zoo. An estimated four million people—including up to 42,000 foreigners—visited the museum up to 1909, and visitor numbers continued to grow in the subsequent decades up to the Second World War.1 Even in 1929, when the Yūshūkan was housed in a temporary structure, it had 308,340 annual visitors.2 Since the 1990s, the Yūshūkan has welcomed fewer visitors than in its prewar heyday, but its high profile has been enhanced by its status as a flashpoint for domestic and international debates around Japan’s war memory and responsibility.

The status of the Yūshūkan as an integral part of a religious establishment sets it apart from most military museums around the world. Indeed, the definition of the Yūshūkan has changed several times since its inception, and it often fulfills multiple roles at once. In this study, I refer to the Yūshūkan first and foremost as a military museum, as this is how it is overwhelmingly viewed by visitors and the media, even if it is also seen by some primarily as a site of veneration and commemoration. In the imperial period (1868–1945), official visitor statistics grouped the Yūshūkan together with other museums and leisure attractions, and the Yūshūkan was still described as “Japan’s oldest and most esteemed war museum” in its own promotional materials in the year 2000.3 Since that time, Yūshūkan publications have described it as having “opened as our nation’s first and oldest military museum,” and that it “retained the character of a military museum from its founding until the end of [the Second World War].”4

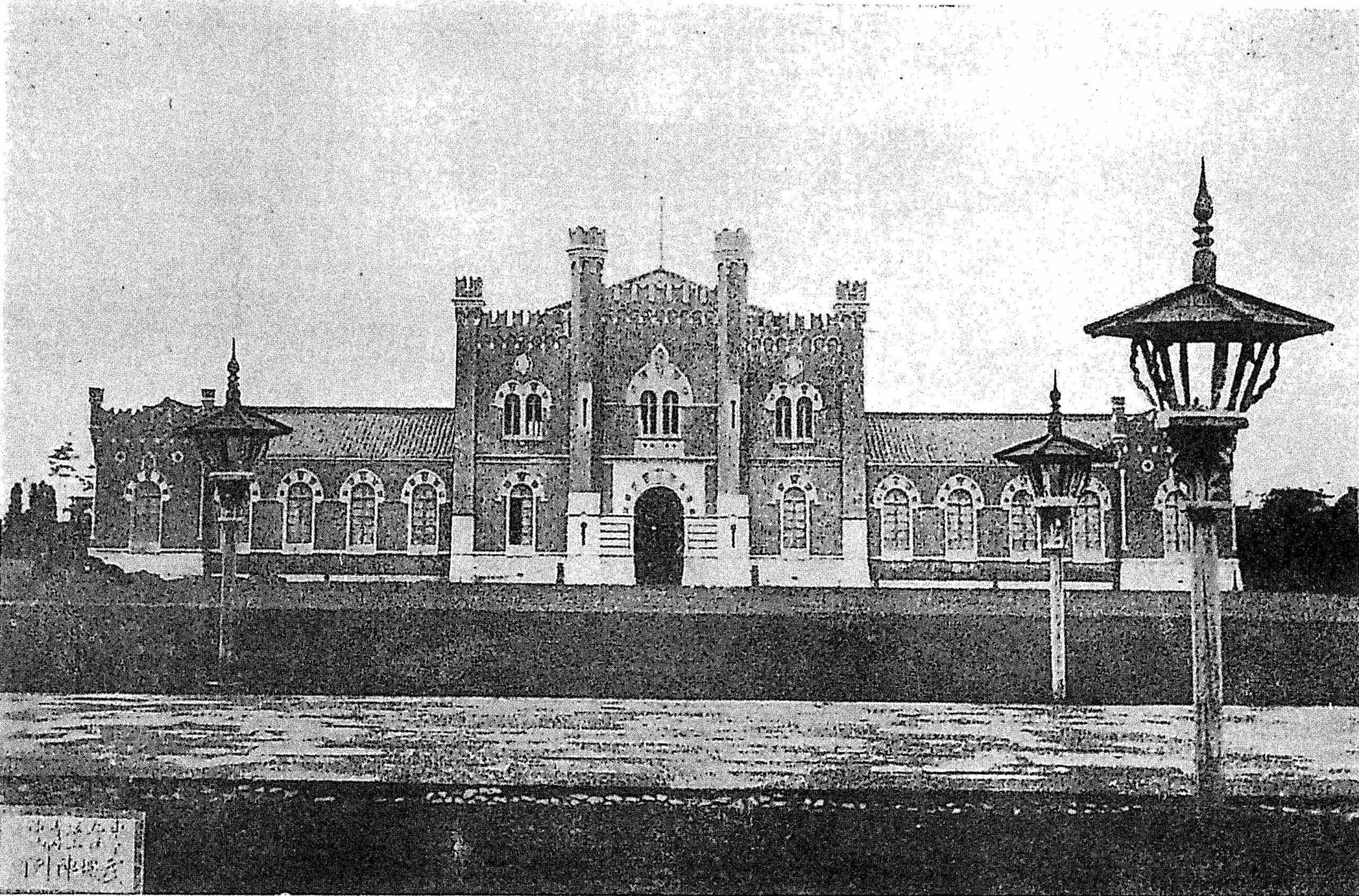

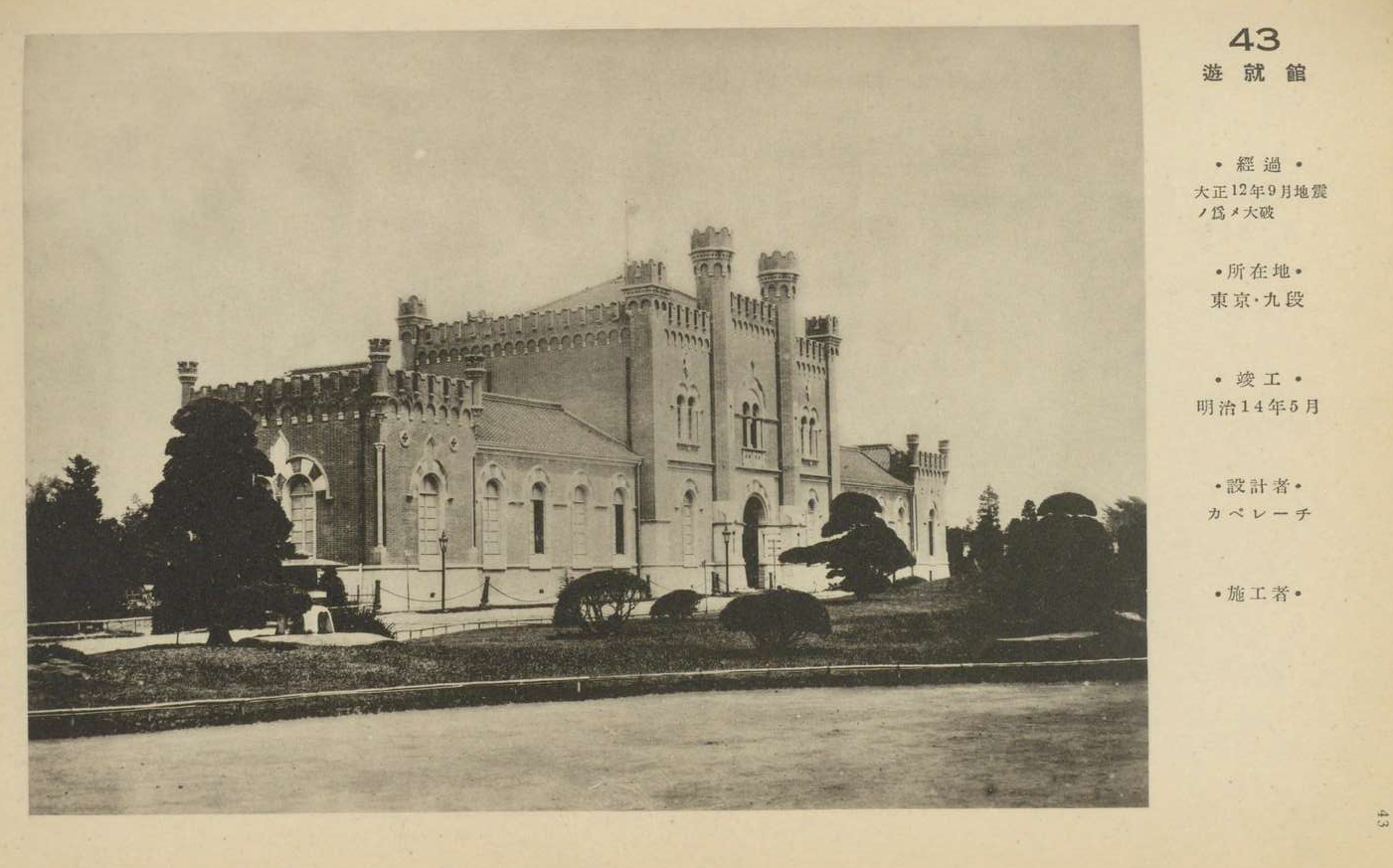

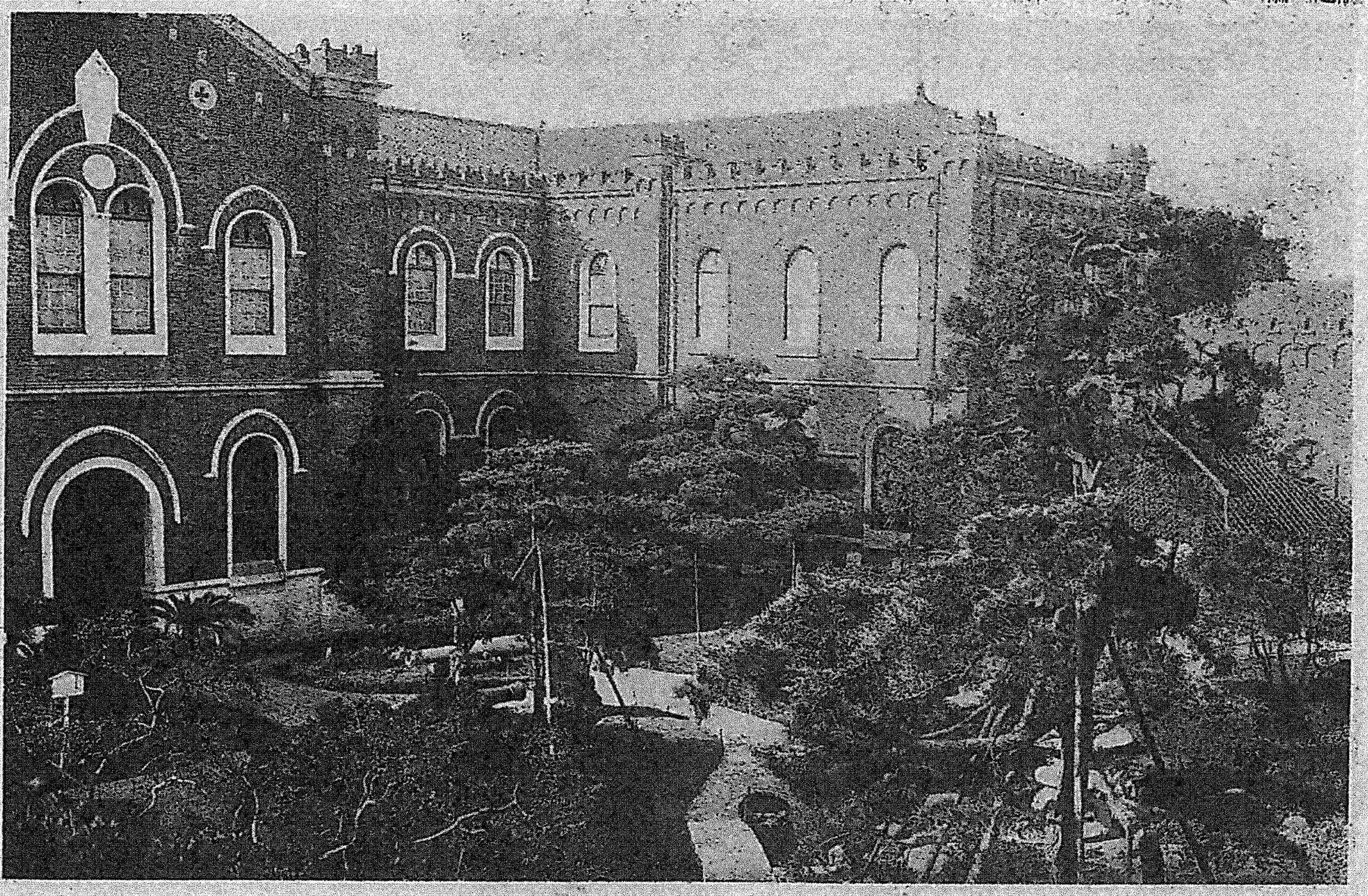

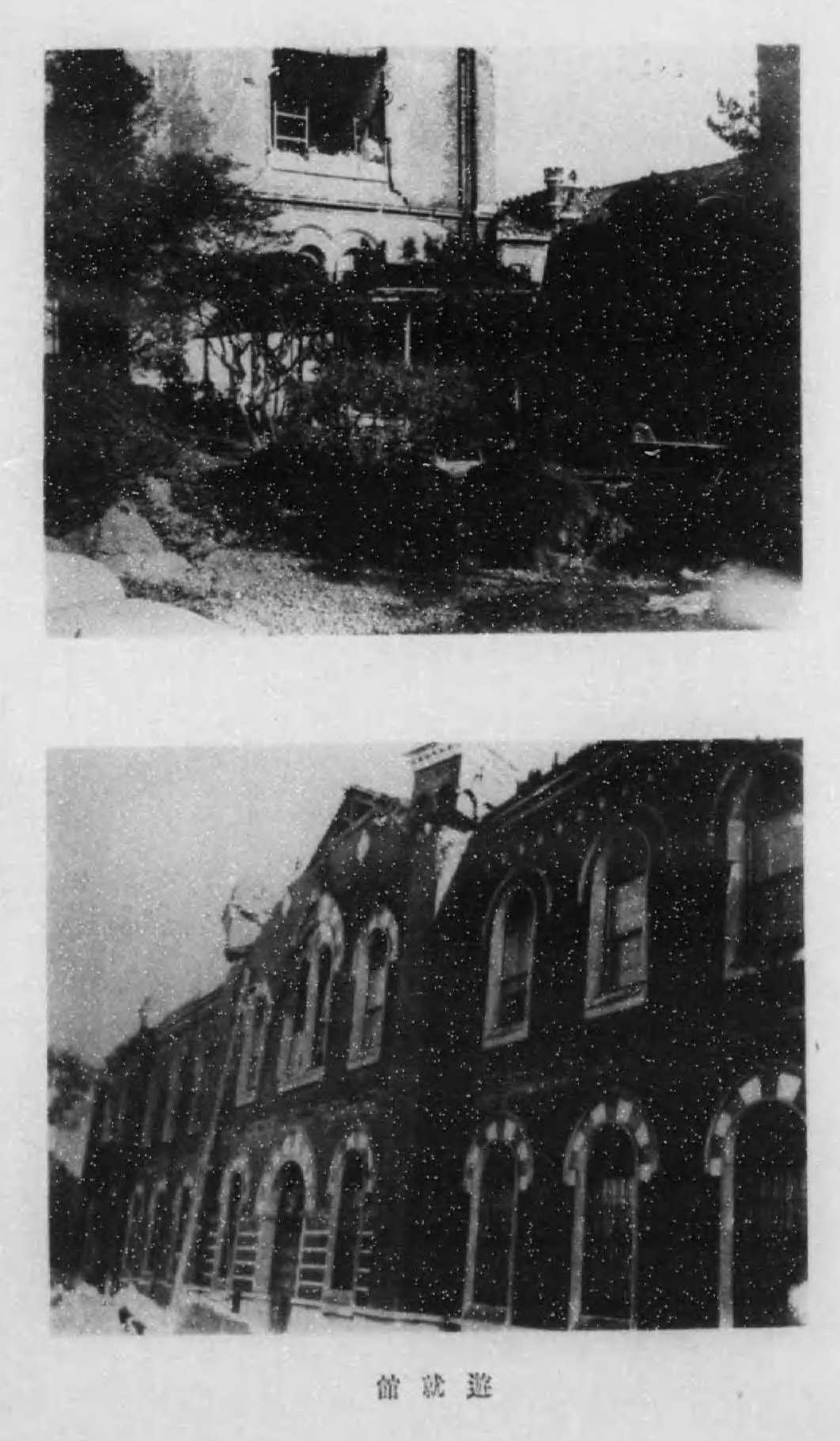

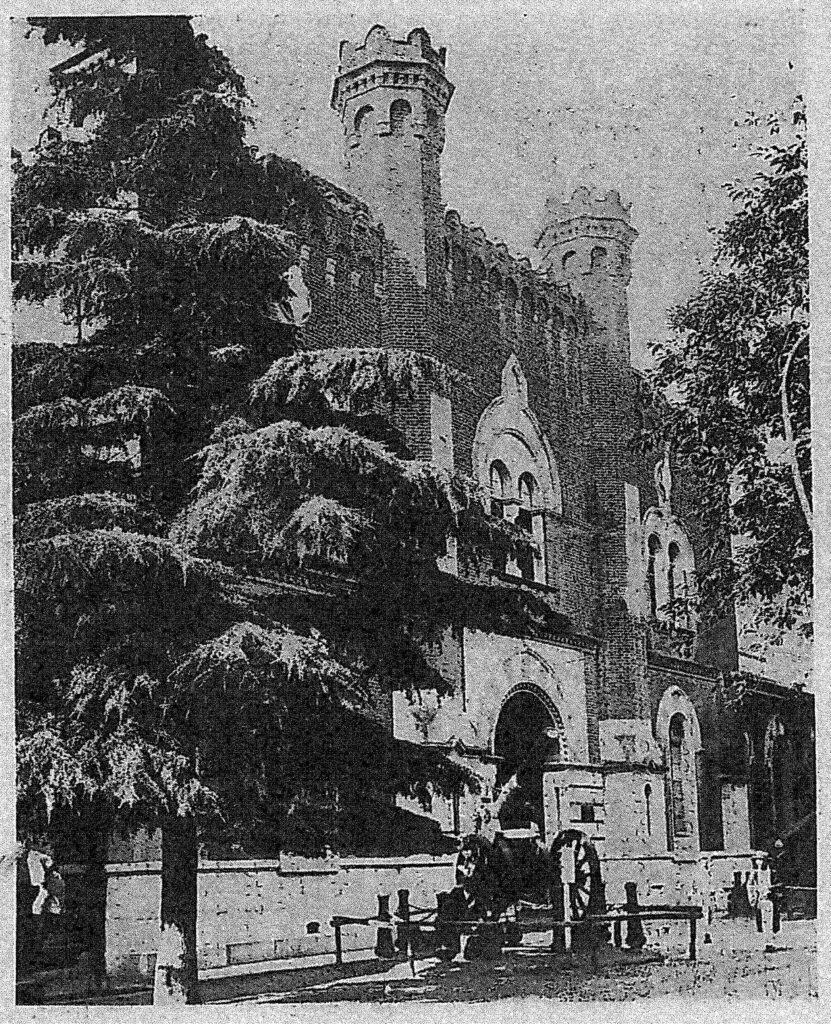

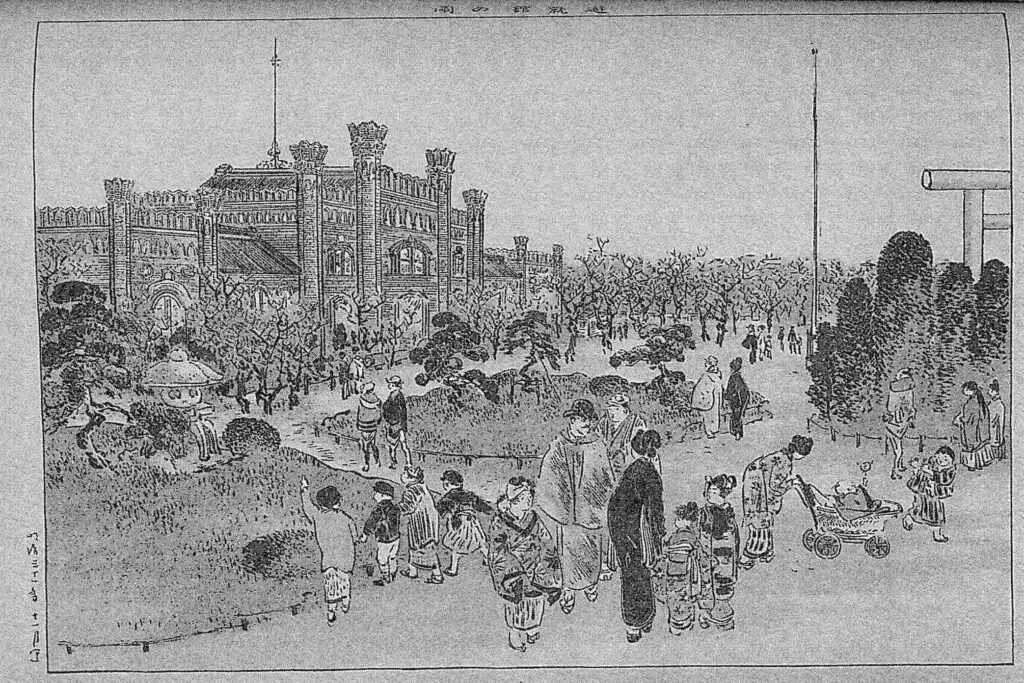

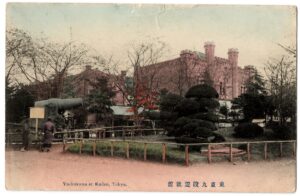

Furthermore, as this study argues, the origins of the Yūshūkan should be seen in the context of the global spread of the military museum as an institution in the late nineteenth century. This is reflected in the design of the original Yūshūkan building as a European castle—the preferred style of similar museums in the West. In fact, the Yūshūkan is one of the earliest purpose-built military museums in the world, the vast majority of which were built after 1881.5 Nevertheless, the Yūshūkan is often overlooked in the scholarship on military museums, which typically focuses on Europe and the Americas. The early history of the Yūshūkan is especially overlooked as the original building was destroyed by the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 and replaced by a modern concrete structure. The current museum was constructed in a Japanese architectural style that better reflects the dynamics of the 1930s and its much closer integration with the Yasukuni Shrine than was the case at the time that the original building was completed.

This study is the first dedicated treatment of the long history of the Yūshūkan from its conceptualization in the 1870s to its place in Japan and the world in the 2020s. In this study, I build on the existing body of previous scholarship related to aspects of the Yūshūkan, which generally discusses the museum as one part of the larger Yasukuni Shrine, as in landmark works by scholars such as John Breen, Mark Mullins, Tino Schölz, and Akiko Takenaka.6 The shrine itself is the focus of most research, which has concentrated on the period since the 1980s, especially the political and diplomatic controversies that took place in the early 2000s following visits to the shrine by prime minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō. These visits were widely condemned in China, Korea, and other countries as lending official support to the so-called “Yasukuni view of history” that downplays Japan’s wartime responsibility. The controversial visits coincided with the major renovation and expansion of the Yūshūkan in 2002, which greatly increased its display space. Furthermore, its exhibits and publications are often seen as representative of the official view of history of Yasukuni Shrine as a whole, and one defense of Koizumi was centered on the fact that he did not enter the Yūshūkan during his visits to the shrine.7

One other relevant area of scholarship that has largely neglected the Yūshūkan is the history of architecture, and museums more specifically. Alice Tseng’s seminal work on the development of the imperial museums does not mention the military museum, nor does Noriko Aso’s excellent study of exhibition culture in the Meiji period.8 Perhaps the most comprehensive work is Kinoshita Naoyuki’s article on the early Meiji history of the Yūshūkan, which brings together many of the known documents.9 Kinoshita’s article was published in 2002, when the controversies around the Yūshūkan were reaching a peak, and the following two decades saw a considerable number of works discussing the more recent history of the museum. More recently, Yamabe Masahiko touches on the Yūshūkan in an overview article discussing war museums and exhibits during the fifteen-year war with China.10 In English, publications include a range of articles in the Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus that address aspects of politics and memory around the Yūshūkan.11

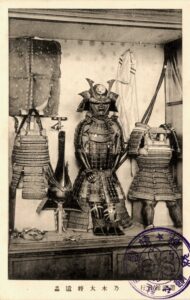

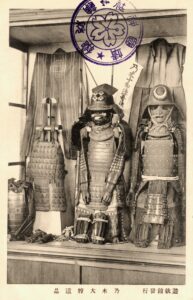

Through a long-term historical treatment, this study argues that the Yūshūkan has always been a part of global discourses through its displays and foreign visitors, and would also change its displays in reaction to real or potential foreign concerns. Although the Yūshūkan represented a continuation of existing Japanese practices in some ways, such as the collection of swords and armor, its establishment was inspired by contact with Western nations. While the vast majority of military museums have a pronounced patriotic narrative and close relationship with the military of their country, the religious aspects of the Yūshūkan as part of Yasukuni further complicate this dynamic. Military museums often need to strike a balance between domestic and international purposes and audiences, which is an exceptionally challenging and controversial task in the case of the Yūshūkan. The history of museums is also a history of the circulation of objects, and it is important to note that the Yūshūkan has not always had control over these flows. Over the course of the past 140 years, the Yūshūkan evolved from a Japanese manifestation of an international phenomenon into a more uniquely Japanese institution that also spoke to imperial and later global audiences through its collections and narratives, which were often marked by key omissions.

As mentioned above, the Yūshūkan’s own promotional materials have referred to it variously as a “military museum” (gunji hakubutsukan) and “war museum” (sensō hakubutsukan), a distinction that is not always made clear in the scholarship on these types of institutions, or indeed by museums themselves.12 The term “military museum” is often used as an umbrella term to include facilities dedicated to broader military history and technology, as well as those focusing on specific conflicts, military units, and types of weapons or other objects. In contrast, the term “war museum” is usually applied to museums dedicated to specific conflicts, most prominently the Imperial War Museum in London, which was founded in 1917 with an explicit focus on the then-ongoing Great War.13 While the Imperial War Museum is often seen as the archetype of this genre, a decade earlier the Yūshūkan was greatly expanded to become—at least in part—a war museum dedicated to the Sino-Japanese War (1894–5) and Russo-Japanese War (1904–5). This was not a complete transformation, and the Yūshūkan retained its earlier collections, just as the Imperial War Museum has subsequently evolved to engage with the Second World War and Britain’s many other modern conflicts. Although approaches to naming vary greatly between institutions, this study argues that the designation of a museum as a “war museum” rather than a more generic “military museum” plays an important role in delineating and legitimizing conflicts through their display and interpretation.

Similarly, the outbreak of war presents a challenge for any military museum, as warfare is no longer merely a topic of historical treatment, but becomes an immediate issue that is impossible to ignore. While many military museums might be able to maintain a focus on the more distant past, the religious dimension of the Yūshūkan meant that contemporary conflicts had to be engaged with in a substantial manner. As Hacker and Vining observe, “Museums, including military museums, rarely exhibit war. Rather, they exhibit the weapons and paraphernalia of the organizations that include war-fighting among their purposes.”14 By including objects from fallen soldiers and war trophies captured from China and Russia, the Yūshūkan exhibited war from an early stage. Later, as conflict with China intensified in the 1930s, the desire to exhibit war resulted in the establishment of a new National Defense Hall (Kokubōkan) next to the Yūshūkan in 1934. This new facility very explicitly exhibited war, showing not only the newest military technology, but also providing sensory experiences such as a chamber for experiencing a gas attack and a simulator for aircraft gunnery.

The national religious and pedagogical roles of these institutions contributed to the harsh polices towards Yasukuni Shrine and the closure of the Yūshūkan under the U.S. Occupation after the Second World War. The shrine was seen as a symbol of so-called State Shinto, the religious elements of which have been extensively debated. Key promoters of Shinto in the Meiji period rejected the notion that it was a religion, but rather described it using terms such as the “national ceremonies” or “national teachings” of Japan.15 As Mark Mullins discusses, scholars have also argued that practice at Yasukuni should be seen in the context of the concept of the “civil religion” of nationalism.16 K. Peter Takayama has focused on Yasukuni as the key site in attempts to resurrect the civil religion of State Shinto in the postwar decades, especially from the 1970s onward.17 Stephen Large touches on the tensions between the formal secularization of the emperor and institutions of State Shinto on the one hand, and the resurgence of conservatives who consider belief in the national myths an essential element of Japaneseness on the other.18 Mullins argues that the divisiveness arising from the actions of the latter group makes the use of the concept of “civil religion” problematic, as their ideology lacks the capacity to bring the nation together.19 In this sense, veneration of the war dead at Yasukuni is deeply enmeshed with the tenets of State Shinto for some visitors, while for others the commemoration of the war dead has more parallels with war memorials elsewhere, such as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in London, Paris, or Rome. Ultimately, by looking at the Yūshūkan as a military museum more generally, and at certain times as a war museum more specifically, we can also understand the dynamics around the evolution of Yasukuni Shrine, war memory, veneration, and commemoration in Japan over the course of the long twentieth century.

The Yūshūkan has from its inception been a site for negotiating Japan’s relationship with the world, and the museum has evolved with and responded to larger developments, while also shaping public views in Japan and other countries. The focus of the current exhibits in the Yūshūkan itself is largely on the period before 1945, especially the Second World War, with some examination of its aftermath. This study also centers on the same period, which has been the least examined in the existing scholarship on the Yūshūkan. I use four key transition points to understand the long history of the museum. The first section looks at the establishment of the Yūshūkan around the opening of the first building in 1882, which was very much in line with global trends surrounding military museums and the reinvention and appropriation of idealized martial—especially medieval—pasts. The second section centers on the large-scale expansion of the Yūshūkan in 1908, in the wake of Japan’s victories over China and Russia, as well as a redefinition of the museum’s mission and role in society. The third section begins with the reconstruction of the Yūshūkan in 1931, following its collapse in the Great Kantō Earthquake eight years before. The 1930s saw the Yūshūkan gain even more prominence as war became ever-present, and the museum reached all corners of Japan through traveling exhibitions and the construction of the new National Defense Hall in 1934. The final section looks at the history of the Yūshūkan after the critical juncture of 1945, when the main building was closed and cleared by the US Occupation before being used by an insurance company until its reopening as a museum in the 1980s, followed by its rapid rise back to national prominence and unprecedented international attention.

Origins of the Yūshūkan

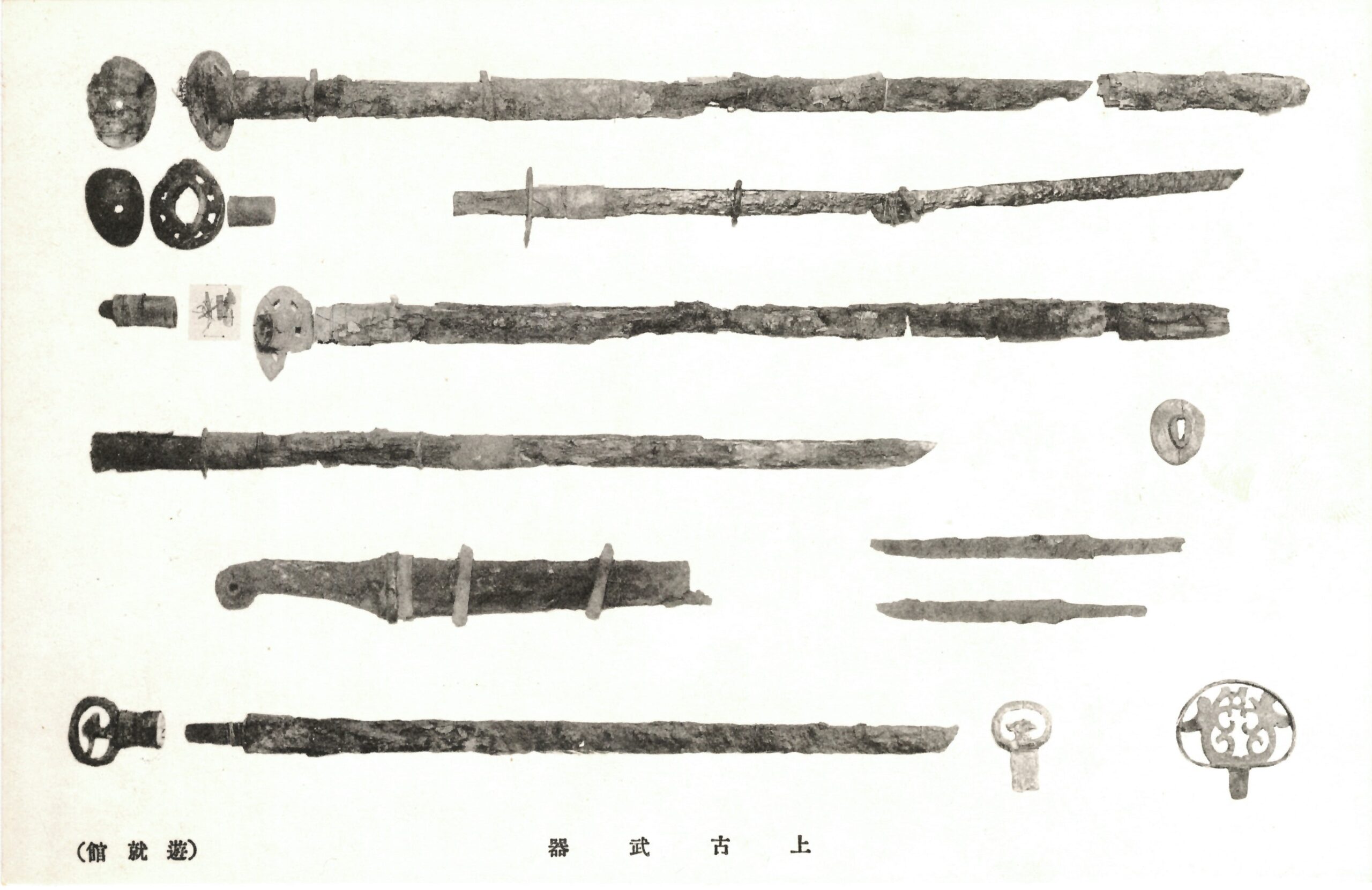

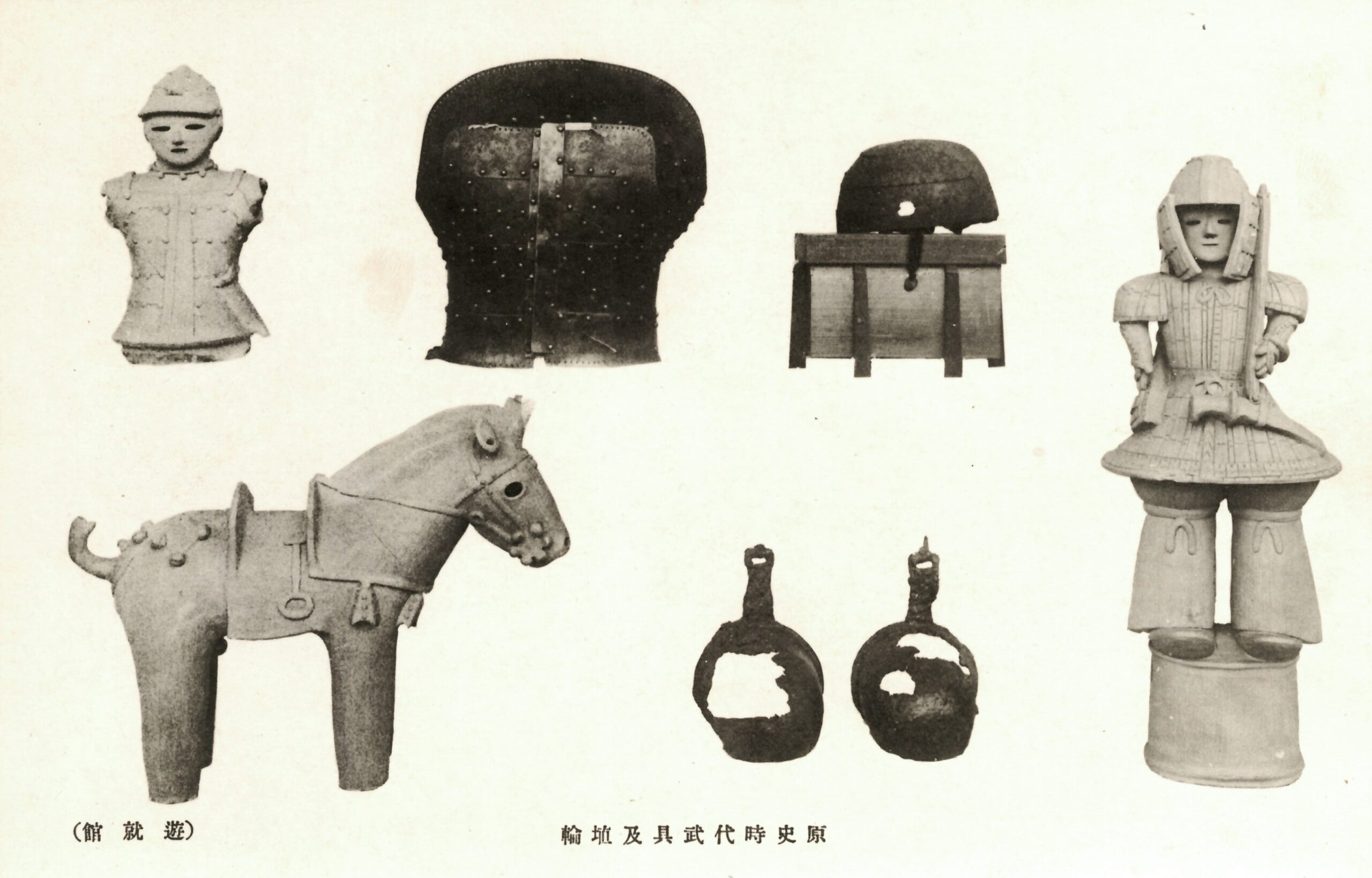

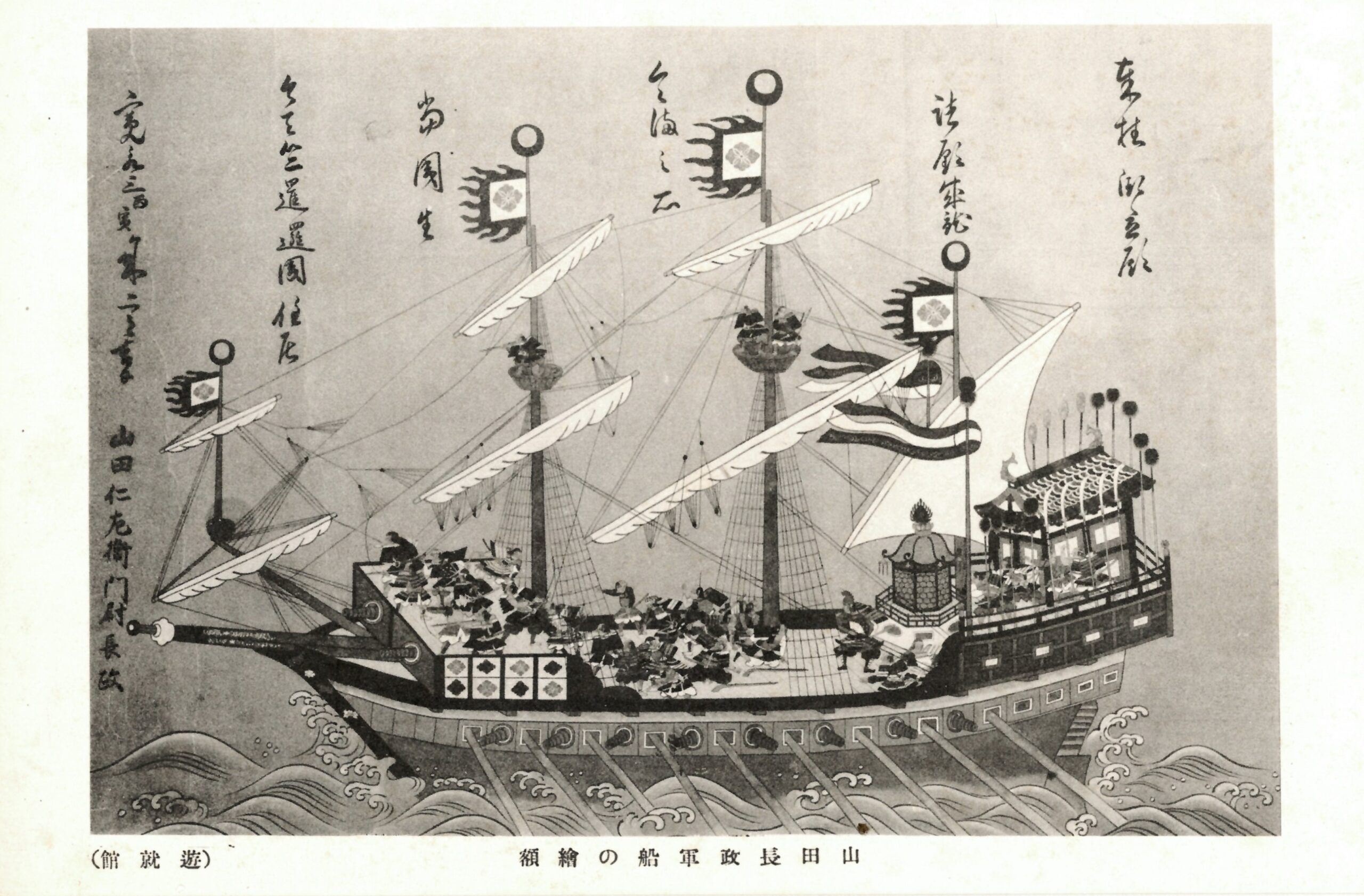

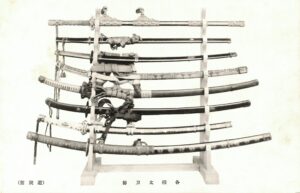

The Yūshūkan opened to the public in 1882, but its origins can be found almost a decade earlier. The collection of famous and rare weapons has a long history in many human societies, as Morgan Pitelka has shown for early modern Japan.20 These existing practices then fed into the development of the modern military museum when this institution emerged as a concept along with the spread of nationalism and the nation state in the nineteenth century. The establishment of national military museums also coincided with the great increase in Japanese interactions with Western countries in the 1870s, as part of the push for “civilization and enlightenment” that marked the first decade of the Meiji period (1868–1912). The single most significant event in this context was the Iwakura Embassy that circumnavigated the globe in 1871–73 with the aim of studying conditions in the West. This high-level government delegation, led by the courtier and statesman Iwakura Tomomi (1825–1883), visited a wide range of sites of scientific, political, and military significance, and the reflections recorded by the official chronicler of the mission, the historian Kume Kunitake (1839–1931), provide a valuable window on the experiences and sentiments of the delegation. The governments that hosted the Iwakura Embassy made sure to show off their own military might, taking the visitors to arms factories and military maneuvers, as well as arsenals and museums. These experiences had a significant and lasting influence on the Japanese delegation, and fed into the establishment of the Yūshūkan a decade later.

One of the world’s oldest and most prominent military museums is the Tower of London, which admitted dignitaries and paying visitors from at least the late eighteenth century. The Tower of London and many other European military museums evolved from arsenals and armories that were often located in medieval castles, and many newly-constructed military museums in the nineteenth century also drew on medieval imagery and symbols. The Hofwaffenmuseum (now Heeresgeschichtliches Museum) in Vienna is one example of this, with medievalist turrets, parapets, and other castle-like elements. This monumental museum opened inside the similarly medievalist Vienna arsenal complex in 1869, shortly before the Iwakura Embassy visited the city. The 1873 World’s Fair in Vienna, the first with significant Japanese participation, brought people from around the globe to Vienna where they could also admire this new institution. As John Ganim has shown, the World’s Fairs were marked by the union of romanticized medievalism and modern technology, which was further complicated by Orientalist discourses.21

Kume recounted visiting many other military museums and arsenals, and the large number of war trophies they contained. At the Woolwich Arsenal in London, he wrote, “we saw on display guns and other objects captured in Russia and China.”22 On the Zeugwart in Berlin, Kume was intrigued by “a giant brass statue of a lion standing over ten feet high. Originally the work of the Danes to commemorate a victory over Prussia long ago, this had been cast by melted-down weapons and had been set up in the Danish capital. Then, after Prussia defeated Denmark in 1864, it was taken down to be brought to Berlin and kept here in the Arsenal.”23 Kume observed that the Europeans were fond of taking trophies from their wars with one another, as well as other peoples, and building monuments to their victories, which led to simmering resentment and ultimately further conflict. According to Kume, it would be better to remove these objects and memorials in the interest of peace and reconciliation. This view should be seen in light of the political situation in Japan, where the new Meiji state was concerned with integrating the defeated Tokugawa family and their allies after the recent civil war.

Although Kume had reservations regarding the display of war trophies and monuments, he was fascinated by military museums. Of the many he visited, his most detailed impressions were of the Tower of London, and he was especially taken by its “huge array of old armour and weapons, each item labelled with its date. There was a breech-loading gun made three hundred years ago, which was a great rarity.” Another object that intrigued Kume was “a set of Japanese armour said to have been sent from Japan as a gift to King James I.” He was less impressed by “a collection of Japanese swords, but they were inferior pieces of the kind found in any antique shop and not worth looking at.”24 Even if they questioned the value of some of the objects themselves, Kume and other Japanese travelers to Europe in the early Meiji period were most intrigued by the notion that a defunct castle could be repurposed into a military museum that could promote nationalism and foster a martial spirit among the people. The idea of establishing a national military museum was being discussed in Japanese government circles as early as 1872. These initial plans foresaw the conversion of the derelict keep (tenshu) of Nagoya Castle into a Japanese Tower of London.25 In the first years after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, castles throughout Japan were seen as useless reminders of the feudal past, and countless structures were torn down for scrap and repurposing of their land. Significantly for the processes of national reconciliation, treatment of castle sites was relatively uniform across Japan, regardless of which side their domain had taken in the Restoration conflict. The largest castle keep in Japan, Nagoya Castle, had its famous golden shachi (mythical dolphin-like figures) removed from the rooftop in 1871 in anticipation of the building being demolished. While the shachi were exhibited in Tokyo and Vienna, the keep was ultimately spared, also due to an intervention by the German diplomat Max von Brandt (1835–1920), but the idea to convert it into a military museum was not realized.26

The 1870s saw a gradual recognition of obsolete castles as symbolically useful sites for celebrating the nation’s martial heritage, and the large-scale destruction of castles in Japan decreased significantly after 1874. Along with Nagoya Castle, two key sites were the seventeenth-century keeps at Hikone and Himeji. These three castle keeps were ultimately preserved with the aid of donations from the Meiji emperor, with one of the driving forces in the case of Himeji Castle being Lieutenant Nakamura Shin’ichirō (1840–1884), whose role is commemorated by a large stone stele that still stands at the entrance to the inner castle today. It is also important to note that most of Japan’s major urban castles, including Nagoya and Himeji, became army bases in the Meiji period.27

The potential military function of castle garrisons was dramatically tested in 1877, when a major rebellion erupted in Southwestern Japan around the Restoration hero Saigō Takamori (1828–1877), a former government minister who became a rallying point especially for disaffected samurai struggling to adapt to the new order. Saigō’s forces tried and ultimately failed to capture the garrison in Kumamoto Castle after a long siege, and the seventeenth century keep burned down as the defenders were preparing for the attack. This so-called Satsuma Rebellion remains the most significant domestic conflict in Japan since the early seventeenth century, and was only put down with considerable loss of life on both sides, including the death of Saigō himself.28

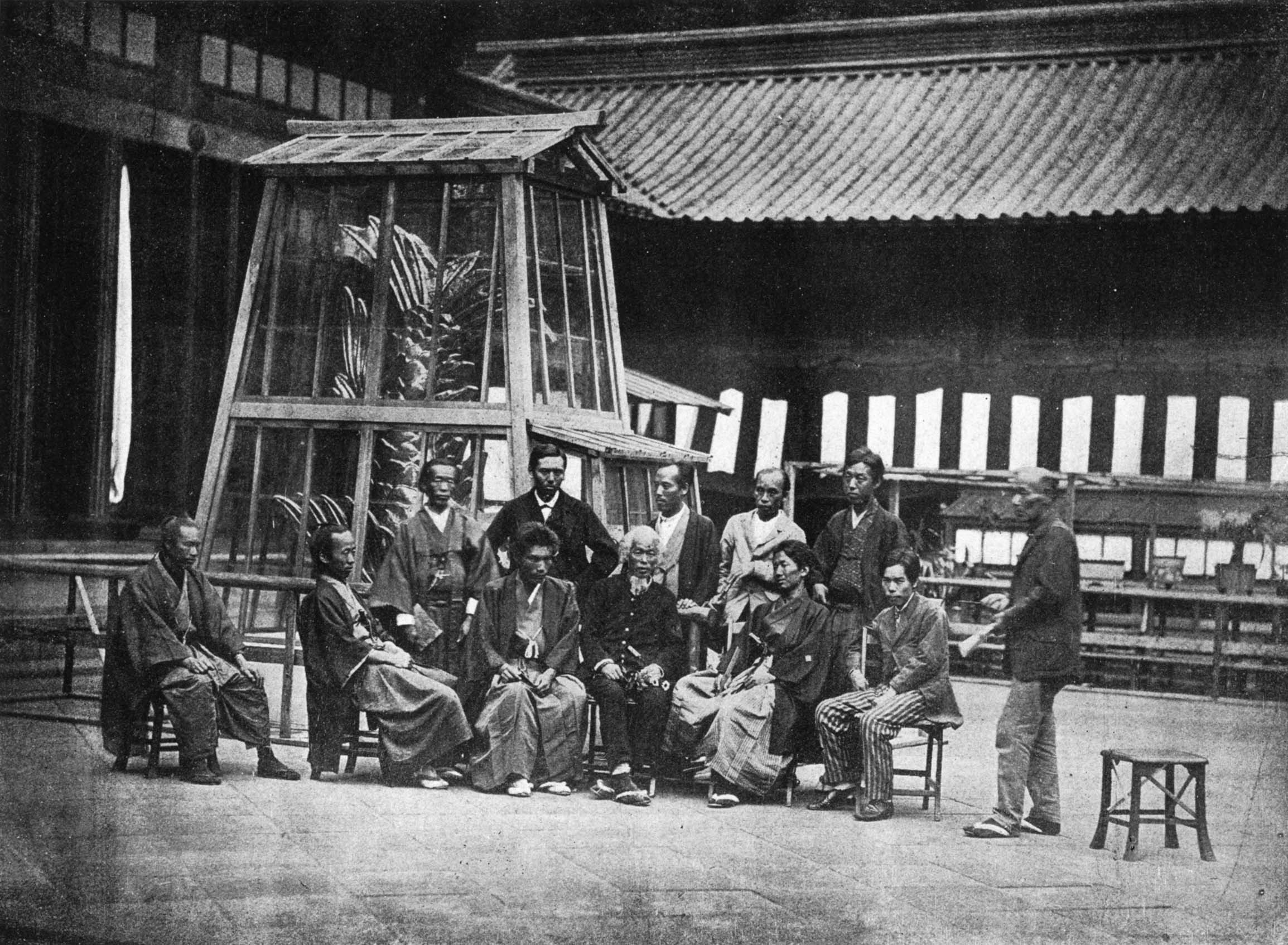

The Satsuma Rebellion was key to the establishment of the Yūshūkan in several ways. The many casualties of the conflict led to a growth in the significance of Yasukuni Shrine as a site of veneration and commemoration of imperial war dead. On a practical level, the conflict also generated a large number of weapons and other objects suitable for display in a military museum, while a substantial amount of money had been donated to the war effort by aristocrats and wealthy elites. These funds were initially earmarked for the care of injured soldiers and veterans, but in 1879 the Chief of the Army General Staff Yamagata Aritomo (1838–1922) asked Iwakura Tomomi, then head of the Peer’s Club (Kazoku Kaikan), whether the money could be repurposed for the construction of a military museum.29 Iwakura, who had himself toured many such sites in the West at the start of the decade, consented to this request. The plans for the Yūshūkan should also be seen in the context of another institution being conceived at that time: the Imperial Museum (now Tokyo National Museum) was also being constructed in Ueno, finally opening to the public in March 1882. The core of the Imperial Museum exhibits was objects exhibited at the Yūshima Seidō Confucian temple in preparation for being sent to the World’s Fair in Vienna, reinforcing the international dimension of the museum.30 Furthermore, the museum building was designed by the British architect Josiah Conder (1852–1920) in accordance with contemporary European trends, although there are also suggestions that the Italian Giovanni Vincenzo Cappelletti (1843–1887) may have drawn the original floor plans.31

In many ways, the development of the Yūshūkan should be seen as complementary to the Imperial Museum. Both opened in 1882 as the first two Western-style museums in Japan, with the Yūshūkan opening in February, while the Imperial Museum followed in March.32 Like the Imperial Museum, the Yūshūkan was designed by a European, and there is no doubt in this case that it was the aforementioned Cappelletti. Cappelletti was one of the many foreign experts brought into Japan in the 1870s to help the country modernize, and his greatest architectural legacy was building the Army Ministry and Yūshūkan, the latter being called one of the “three great buildings of early Meiji,” along with the Imperial College of Engineering and the Orthodox Holy Resurrection Cathedral (Nikorai-dō).33 Cappelletti’s design for the Yūshūkan was very much in keeping with Western trends, and the building resembled an Italian castle with turrets, parapets, and other medievalist elements. These decorations contributed to significant cost overruns, but Yamagata made a powerful argument that they were absolutely essential to the structure and could not be dropped from the design.34

Although the medievalist revival in nineteenth-century Europe was centered on Britain and Germany, its symbolic language and influence spread across the continent and throughout the wider world. In Italy, many regions tended to draw more heavily on their classical and Renaissance past, but in parts of the North, especially, the medieval was a dominant influence. Cappelletti himself studied under Camillo Boito (1836–1914) at the Brera Academy in Milan, the center of gothic architecture in the region. The legacy of the idealized medieval past can still be seen in Milan in the Sforza Castle (restored by Boito’s student Luca Beltrami (1854–1933) in the 1890s), but also in Turin and other cities that celebrate this heritage. In this sense, the Yūshūkan was very much in line with global trends and emerging standards in the design and execution of military museums.35

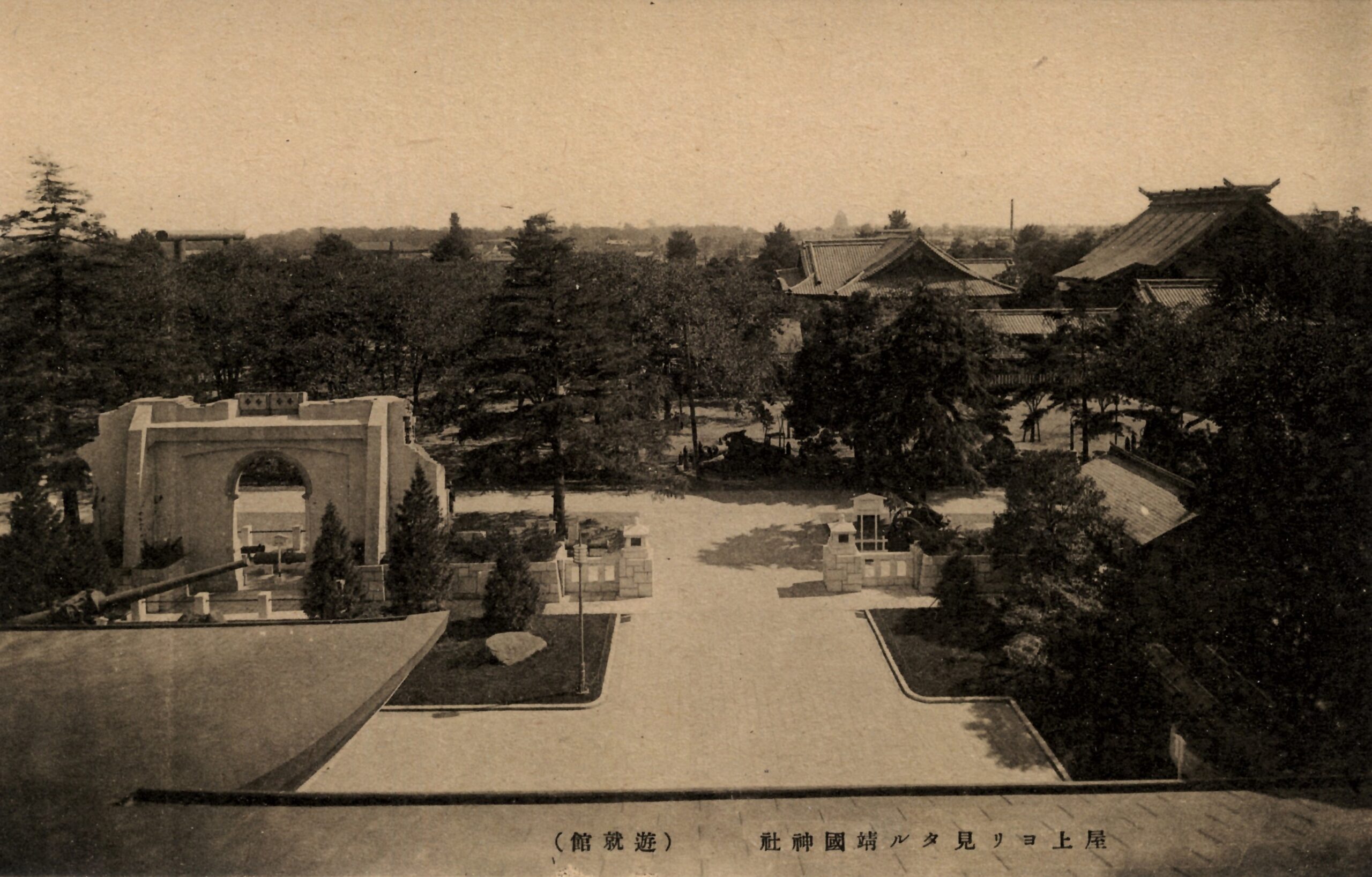

Another key factor in the establishment of the Yūshūkan concerns its location next to Yasukuni Shrine, described by Basil Hall Chamberlain as follows:

“On the flat top of the Kudan hill, a short way beyond the British Embassy, stands the Shinto temple of Yasukuni Jinja, also known as Shōkonsha, or Spirit-Invoking Shrine. The Honden, or Main Shrine, of this temple, built in accordance with the severest canons of pure Shintō architecture, was erected in 1869 for the worship of the spirits of those who had fallen fighting for the Mikado’s cause in the revolutionary war of the previous year.”36

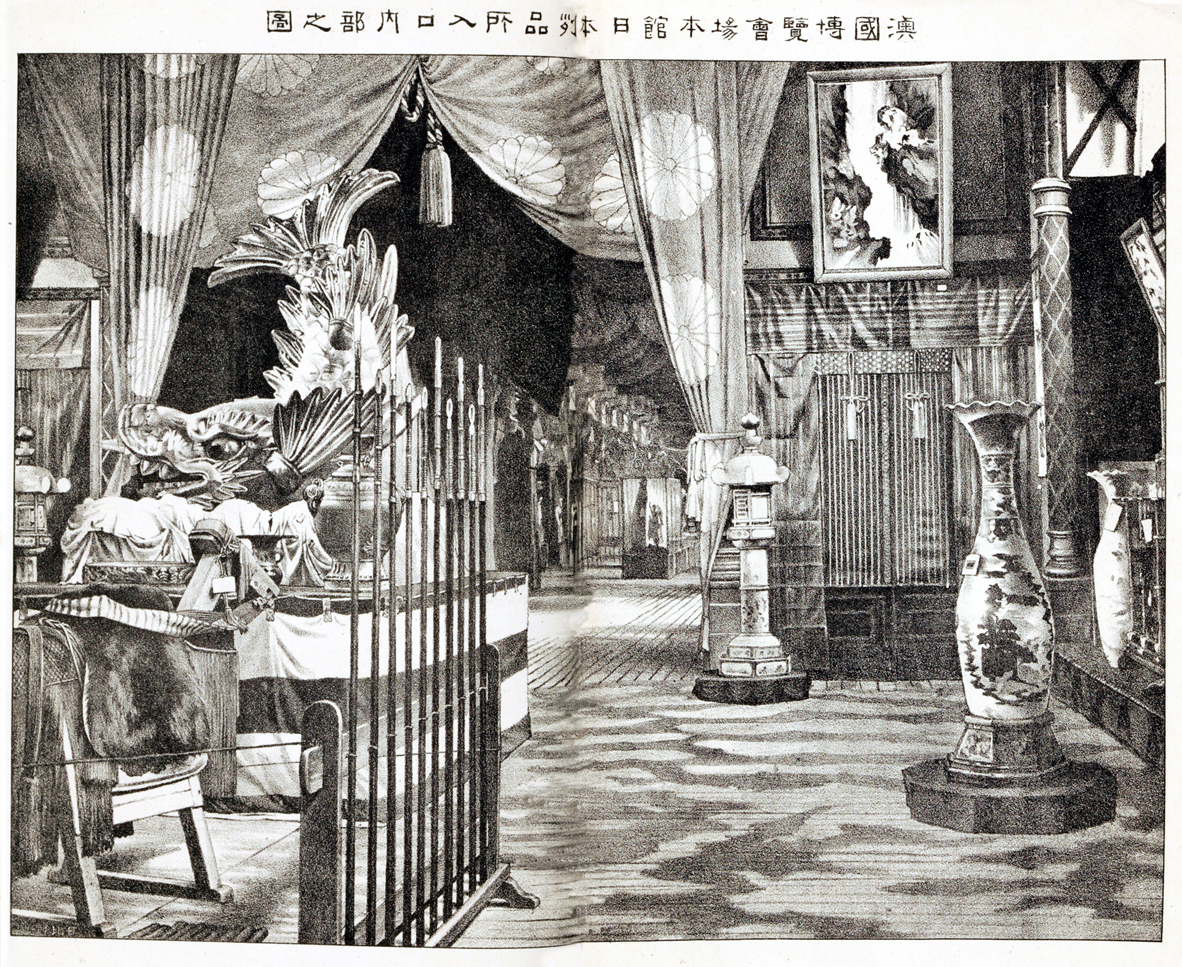

Not only did this location provide a vista across the city, but the approach to the shrine was directly across from the gate to Imperial Guard garrison in the North Bailey of the Imperial Castle, the former Edo Castle of the Tokugawa shoguns, thereby physically tying the site to both the modern military and premodern martial spaces. That said, the decision to locate the Yūshūkan on this site was not predetermined, and was influenced in no small part by the availability of space on the generous shrine grounds.37 The shared military aspects of the shrine and museum notwithstanding, the former was portrayed as symbolizing ancient traditions—as Chamberlain notes—whereas the museum was conceived as a modern institution conforming to international standards in both design and purpose. It is also significant that when the government selected the types of objects to be preserved and exhibited at Yūshima Seidō in the early 1870s in anticipation of the Vienna World’s Fair, one of the categories was weapons.38

Initially described as a “picture hall” (emadō) and “weapons display hall” (buki chinretsukan) in Japanese documents, Kinoshita Naoyuki argues that Cappelletti himself always saw the Yūshūkan as a museo.39 The first exhibitions at the Yūshūkan were in keeping with this role, and included a wide variety of objects from around the world. Items ranged from Gatling guns and swords to documents and oil paintings, including one of William II of the Netherlands (1792–1849) that had been presented to the Tokugawa shogunate in 1845.40 Perhaps the largest single category of objects was handguns, mostly from Europe and the United States.41 The discussion of the collection in the official 1883 record of the Yūshūkan is firmly focused on the history of weapons and their development through time, as befitting an essentially secular military museum, and there is no mention of the connection to Yasukuni in this context.42 According to Kinoshita, an earlier plan in the 1870s to build a hall for paintings had mooted Yasukuni’s grounds as suitable for an institution emblematic of new ideals of civilization and enlightenment, as opposed to the older and more traditional neighborhoods of Asakusa or Ryōgoku. Kinoshita suggests that while the painting hall was never realized, the discussions around the idea influenced plans for the Yūshūkan several years later.43

Even if it was not as explicitly tied to Yasukuni’s larger role as in later periods, the new military museum was given a literary name that helped integrate it into the site.44 The designation “Yūshūkan” (遊就館) drew on the ideas of the third-century Chinese thinker Xunzi, specifically a passage on the nature of the gentleman to “associate with well-bred men when he travels” (游必就士).45 Not only is this phrase taken from classical Chinese—as were the names of the Rokumeikan (“Deer-Cry Pavilion”) and many other contemporary Western-style buildings throughout Japan—but the reference to the traveling gentleman evokes the transnational elements of the military museum as an institution. The name was purportedly chosen by Major General Tanaka Mitsuaki (1843–1939), an influential figure in the Meiji Restoration who had also accompanied the Iwakura Embassy.46

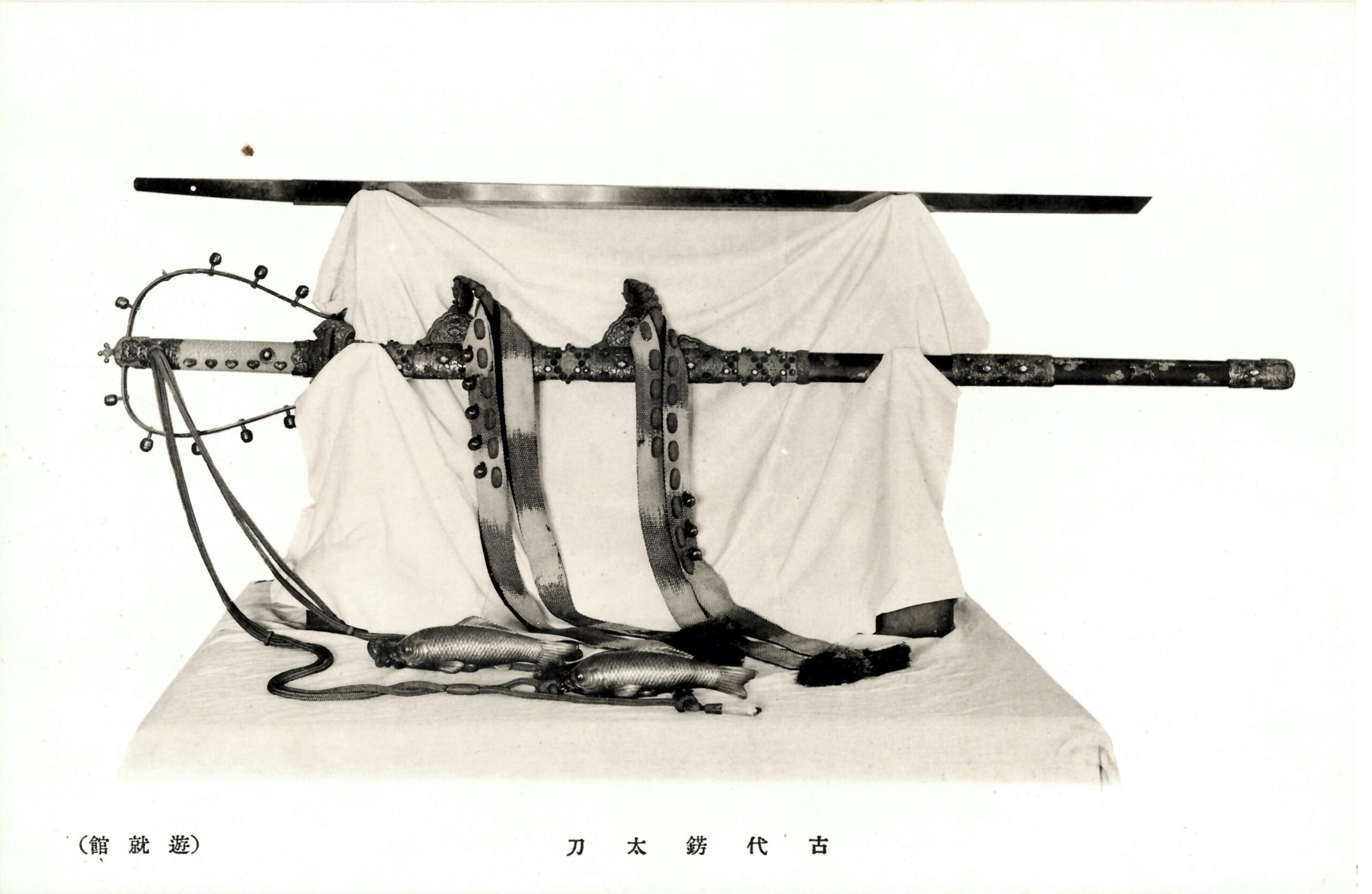

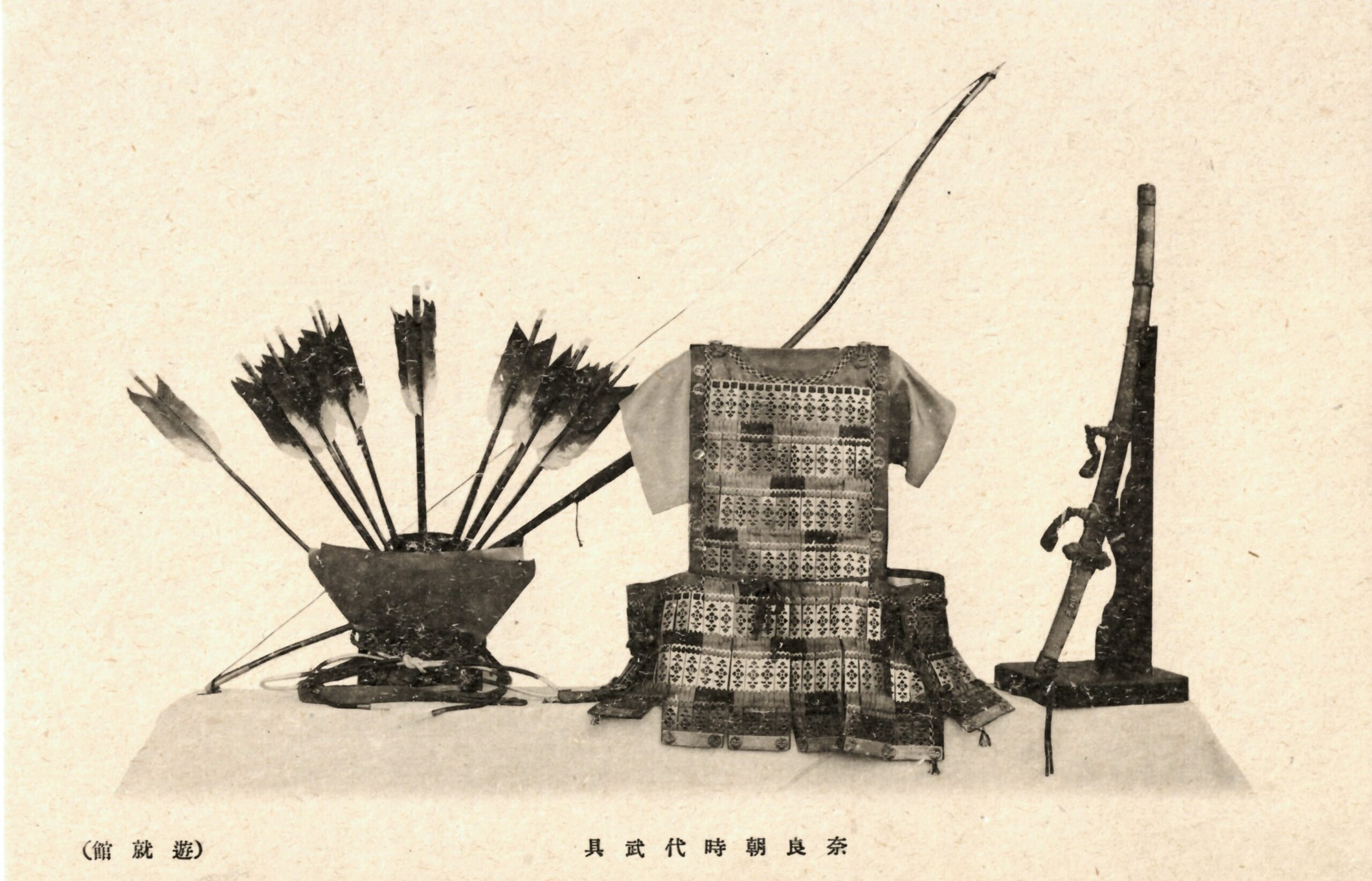

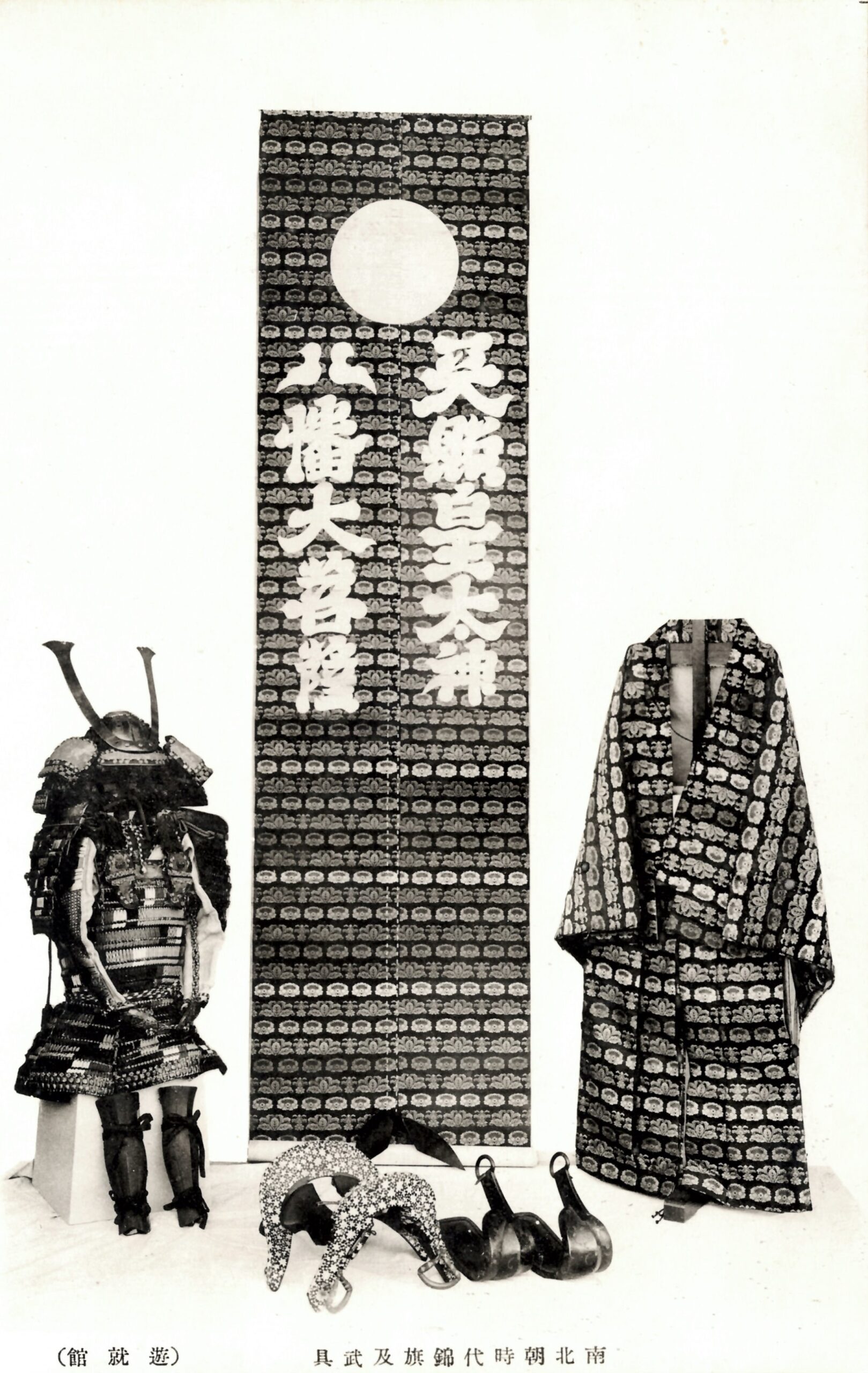

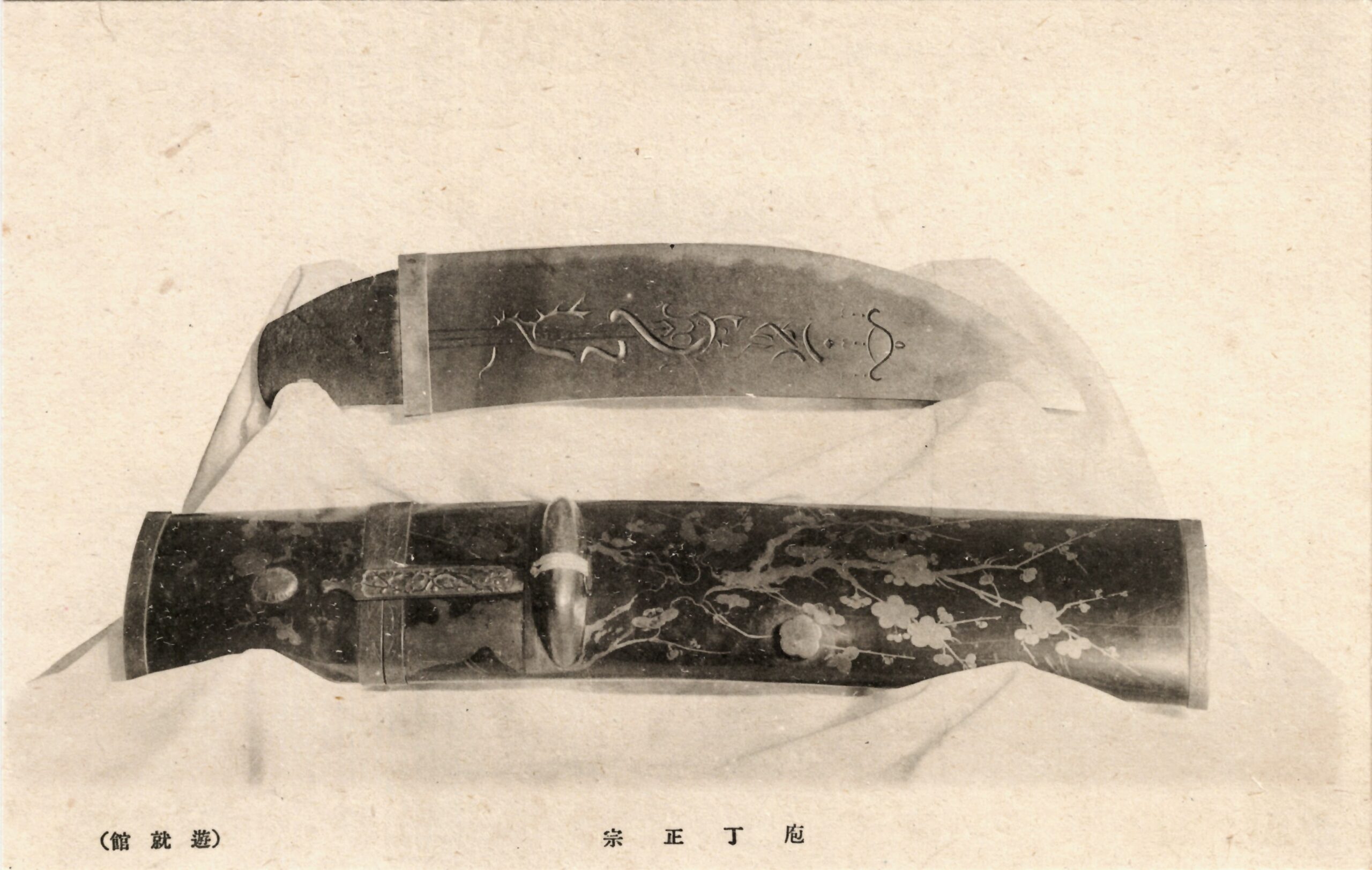

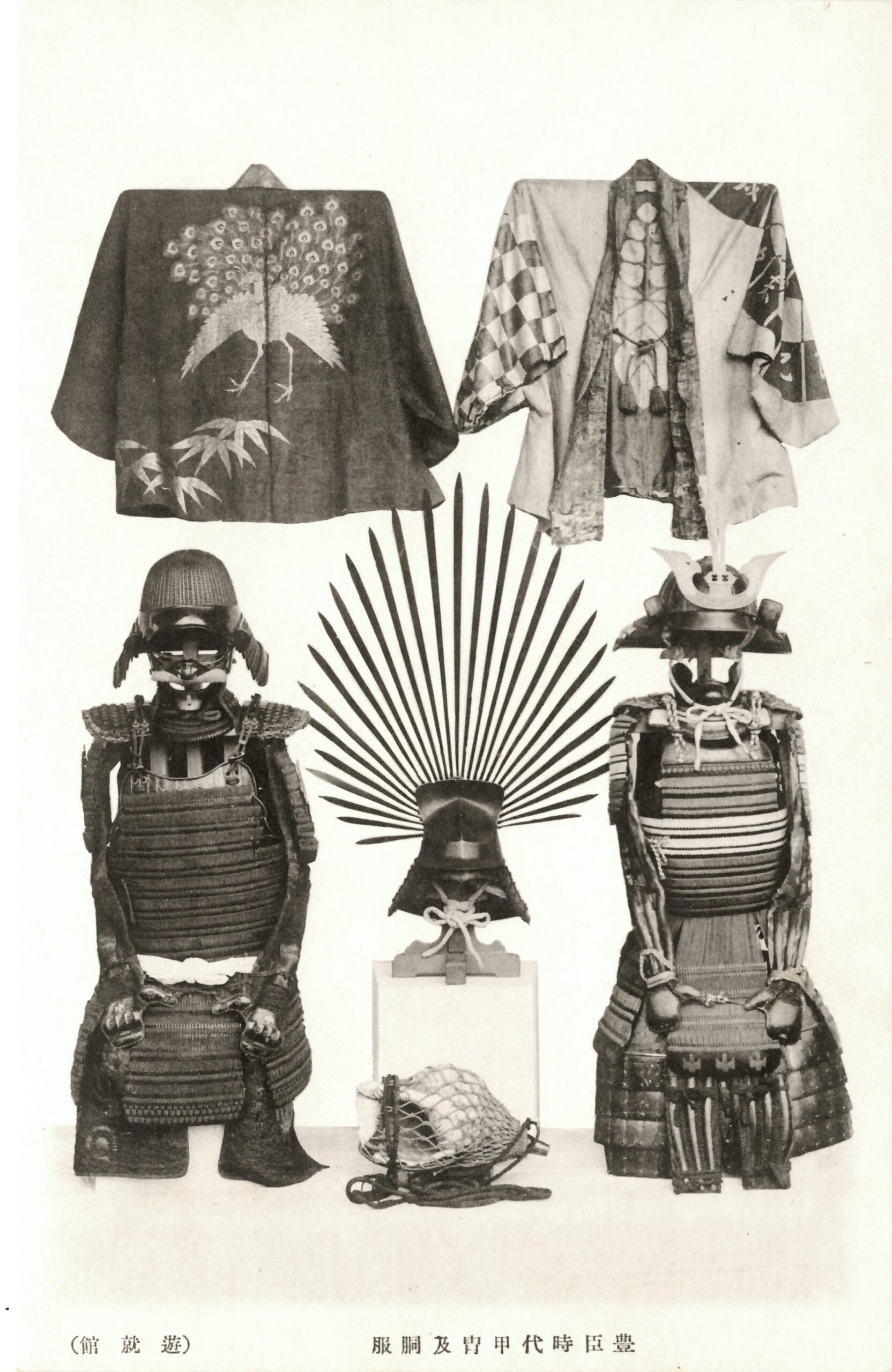

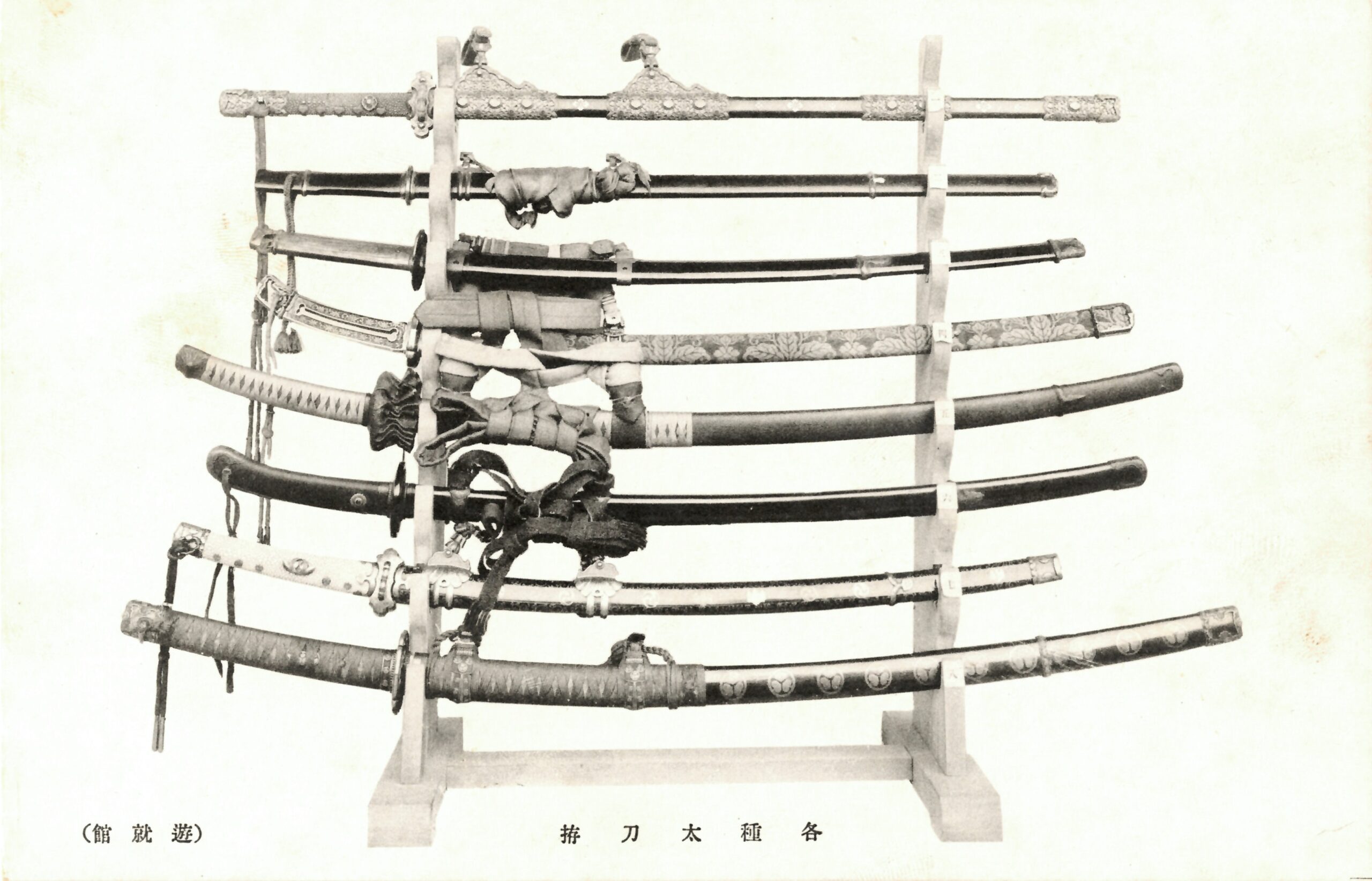

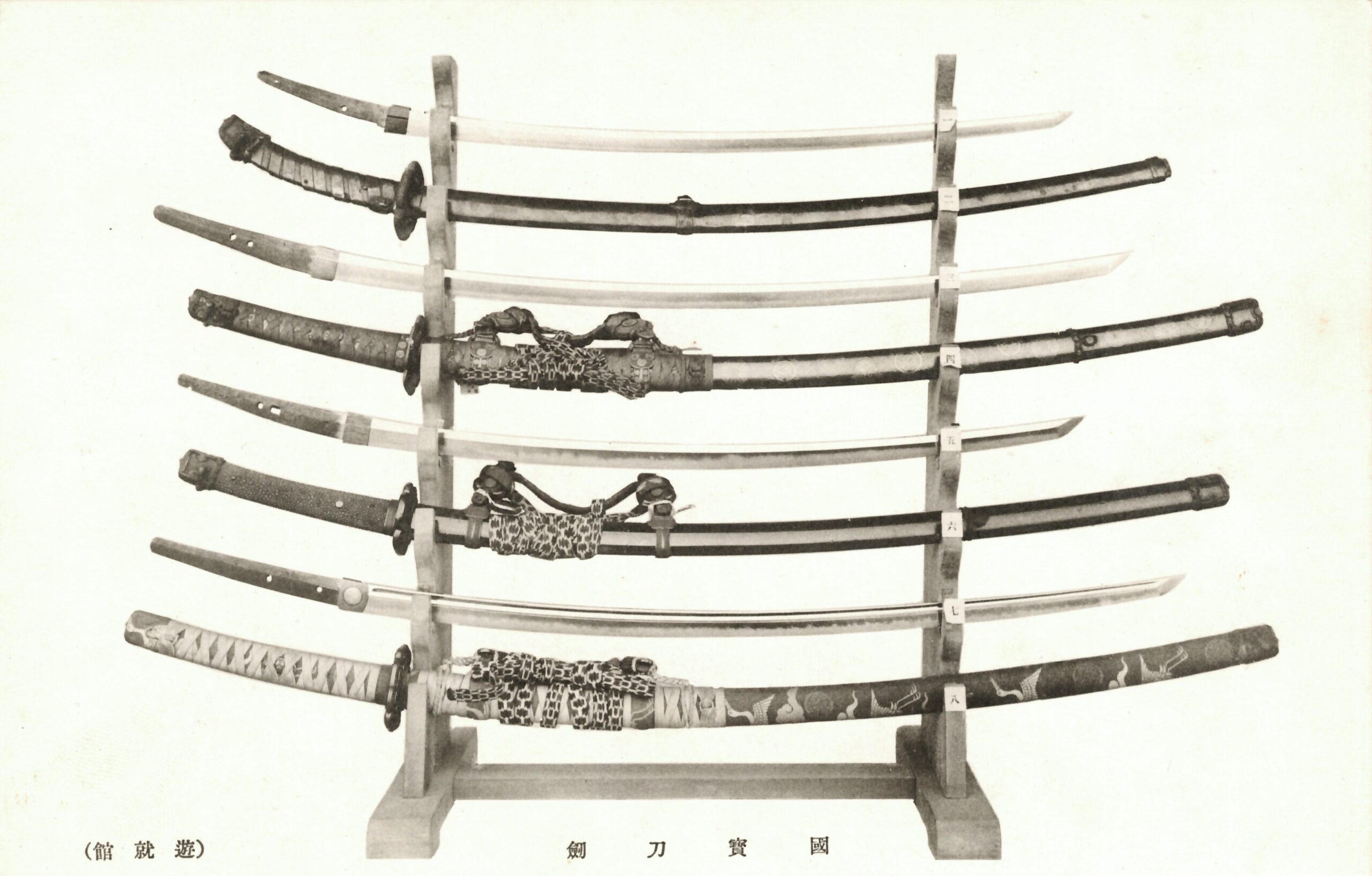

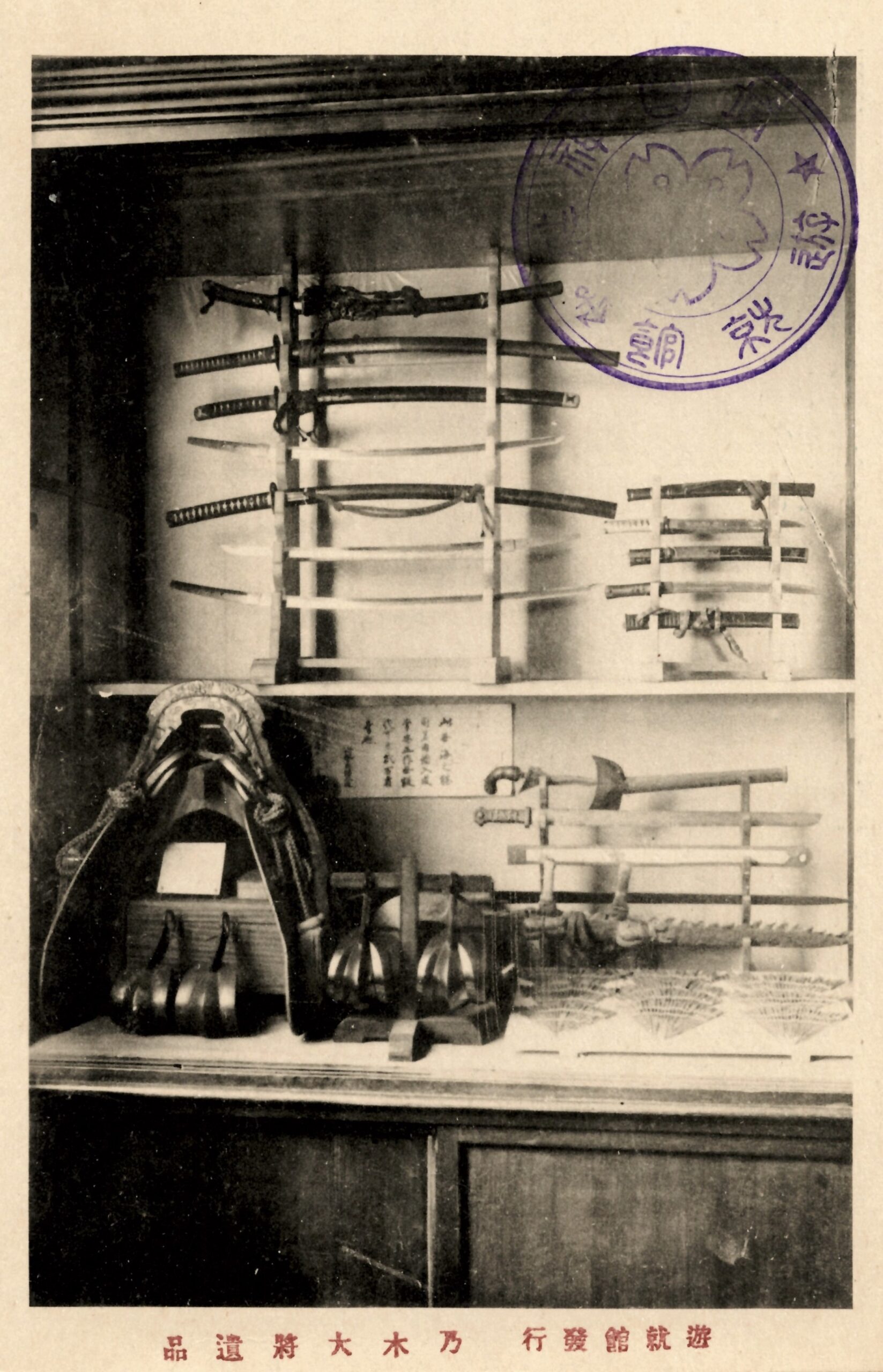

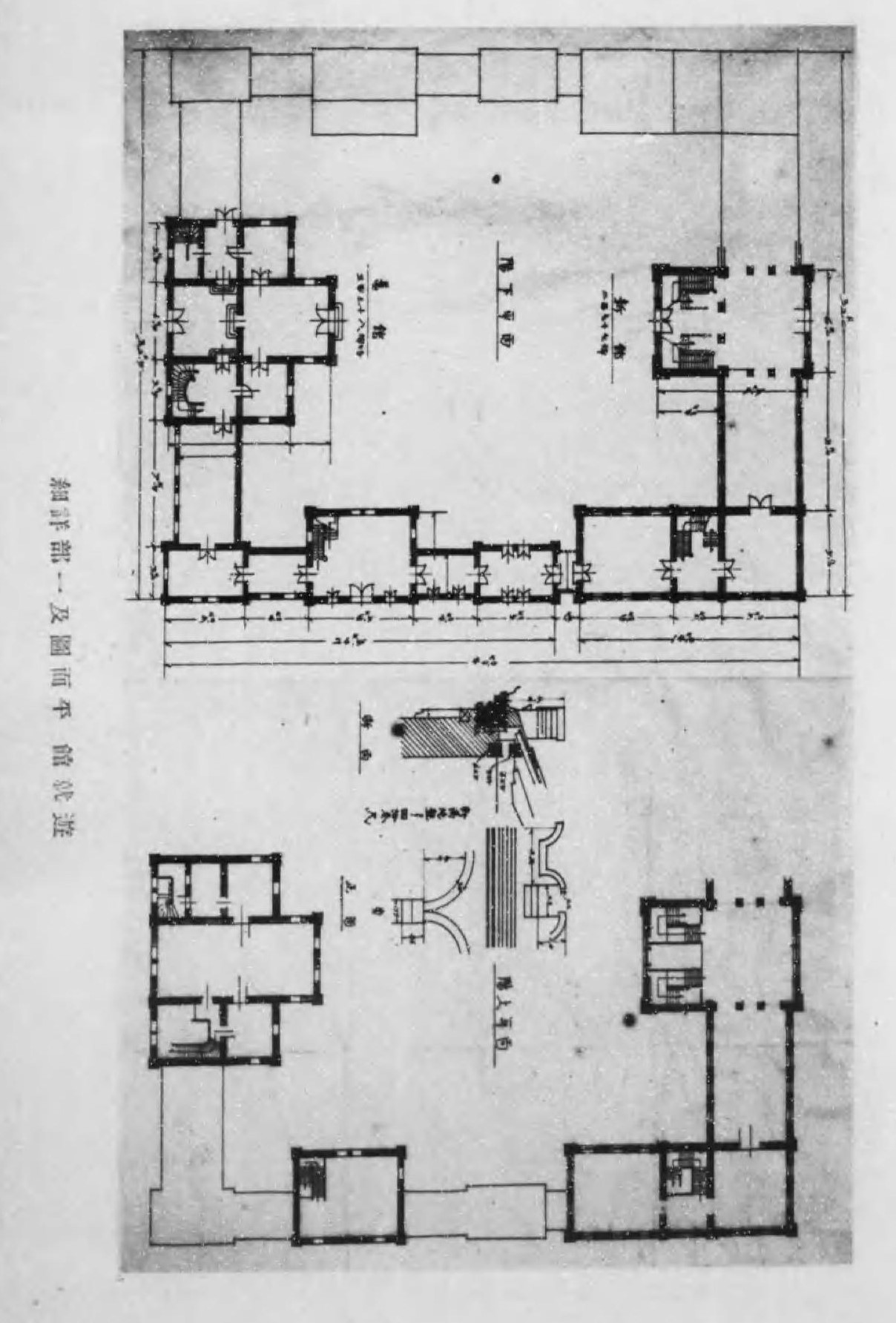

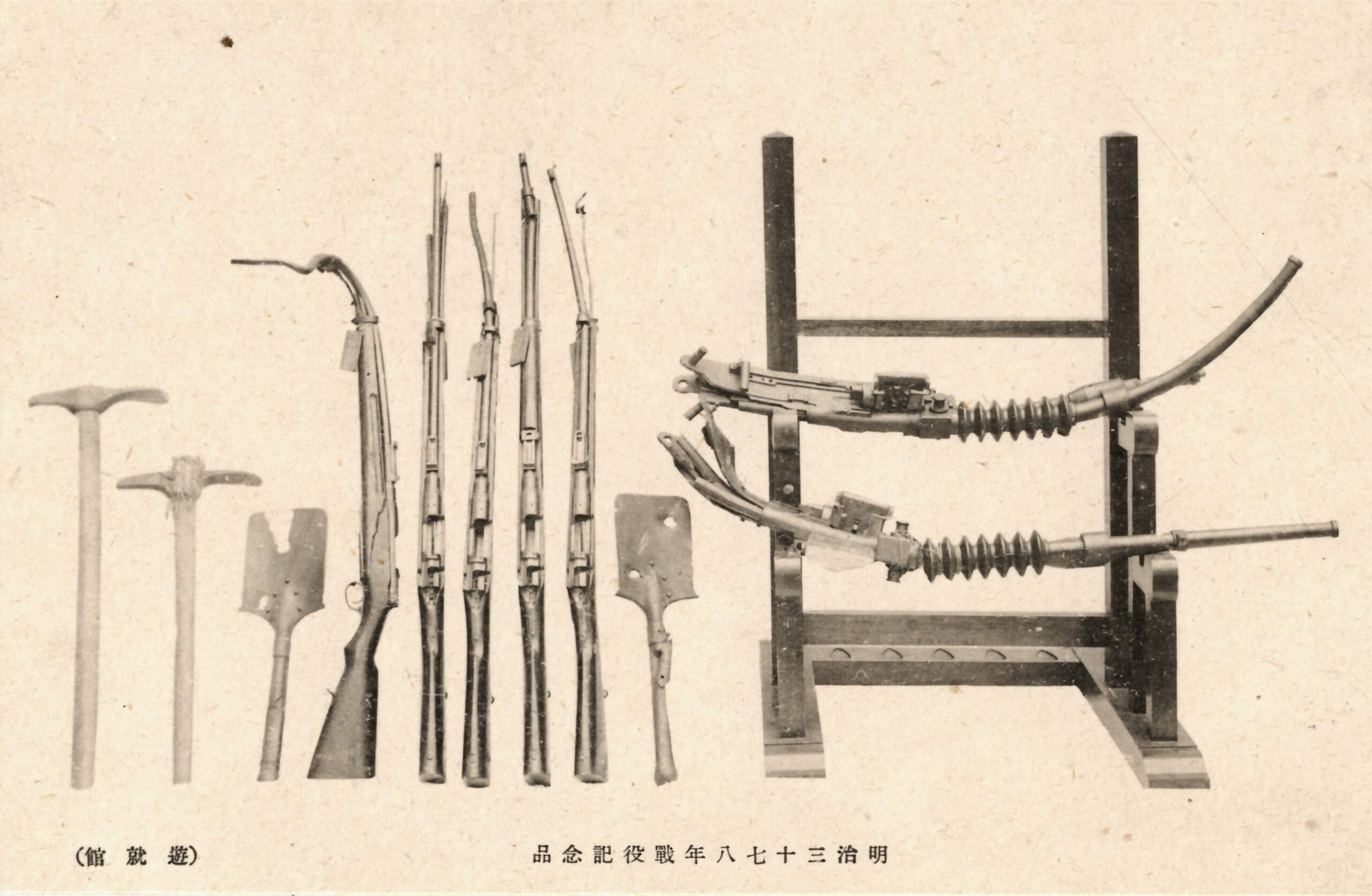

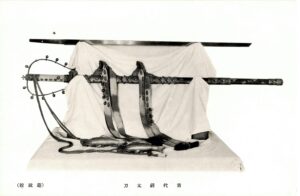

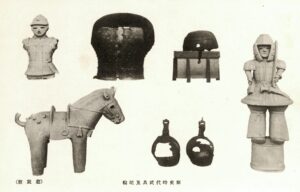

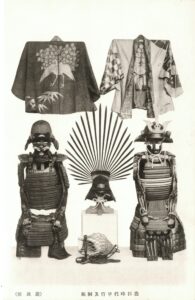

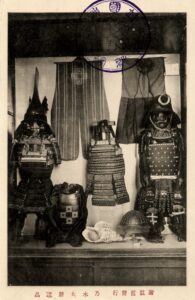

In spite of its prominent location and striking appearance, the original Yūshūkan building was relatively small, with roughly 886 square meters (268 tsubo) of exhibition space. An expansion in 1887 increased this to 1107 square meters (335 tsubo), and by the 1890s the museum was regularly hosting events by sword appreciation societies and also welcoming domestic and foreign visitors.47 An 1890 educational text for children included a detailed account of a visit to the Yūshūkan, which was open on Saturdays, Sundays, and Wednesdays each week. While the account mentions swords and armor, its main focus is on the many different types of firearms and cannons, from the era of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s invasions of Korea in the 1590s through Edo-period muskets and on to Gatling guns, grenades, and Murata rifles.48 A guidebook published that same year described the museum as containing ancient and modern weapons, including “swords and armor from famous heroes of old” as well as “weapons and other objects looted from Taiwan.”49 Within a decade, the Yūshūkan had become firmly established as a tourist destination, with its educational role seemingly focused on the global history of weapons rather than purely patriotic aims.

From Military Museum to War Museum

Arguably the greatest shifts in the Yūshūkan’s role took place in the years immediately after the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5. Although Japan had successfully engaged in major conflicts overseas in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–5 and as part of the international coalition in the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, a 1903 guidebook still described the Yūshūkan as “a Museum of Arms, to which the visitor is admitted on payment of a small fee. In the museum will be found interesting specimens of old Japanese swords, spears, models of castles, etc.”50 For foreign visitors, whose numbers increased considerably after the revision of unequal treaties in 1899, traditional Japanese weapons were the greatest draw, and the Yūshūkan had one of the most impressive publicly accessible collections.51 That said, the interior exhibition space remained relatively limited, even if captured Chinese cannons and other objects were increasingly displayed around the grounds.

The conflicts with China were significant in shifting the balance of power in East Asia, but it was the victory over Russia that fundamentally changed Japan’s status in the world, and this was reflected in the Yūshūkan. When the educator and journalist Mori Jitarō (1870–1955) visited the Horse Guards building in London, he referred to it as “Britain’s Yūshūkan,” thereby centering the Japanese institution as the reference point. Mori observed with apparent satisfaction that the Horse Guards contained items and trophies from countries that the British had defeated all around the world, but did not have any objects from Japan.52 Throughout the early twentieth century, Japanese visitors to Germany similarly referred to the Zeughaus as “Berlin’s Yūshūkan,” reflecting popular views of the Yūshūkan as a national military museum comparable with Western counterparts.53 In 1929, the army officer Kokura Hisashi (1892–1943) referred to the military museums he visited in Berlin, Munich, and Vienna as the “Yūshūkan” of those countries.54 The discussion of Yasukuni Shrine in Chamberlain’s 1907 guidebook reveals how the site had evolved by that point:

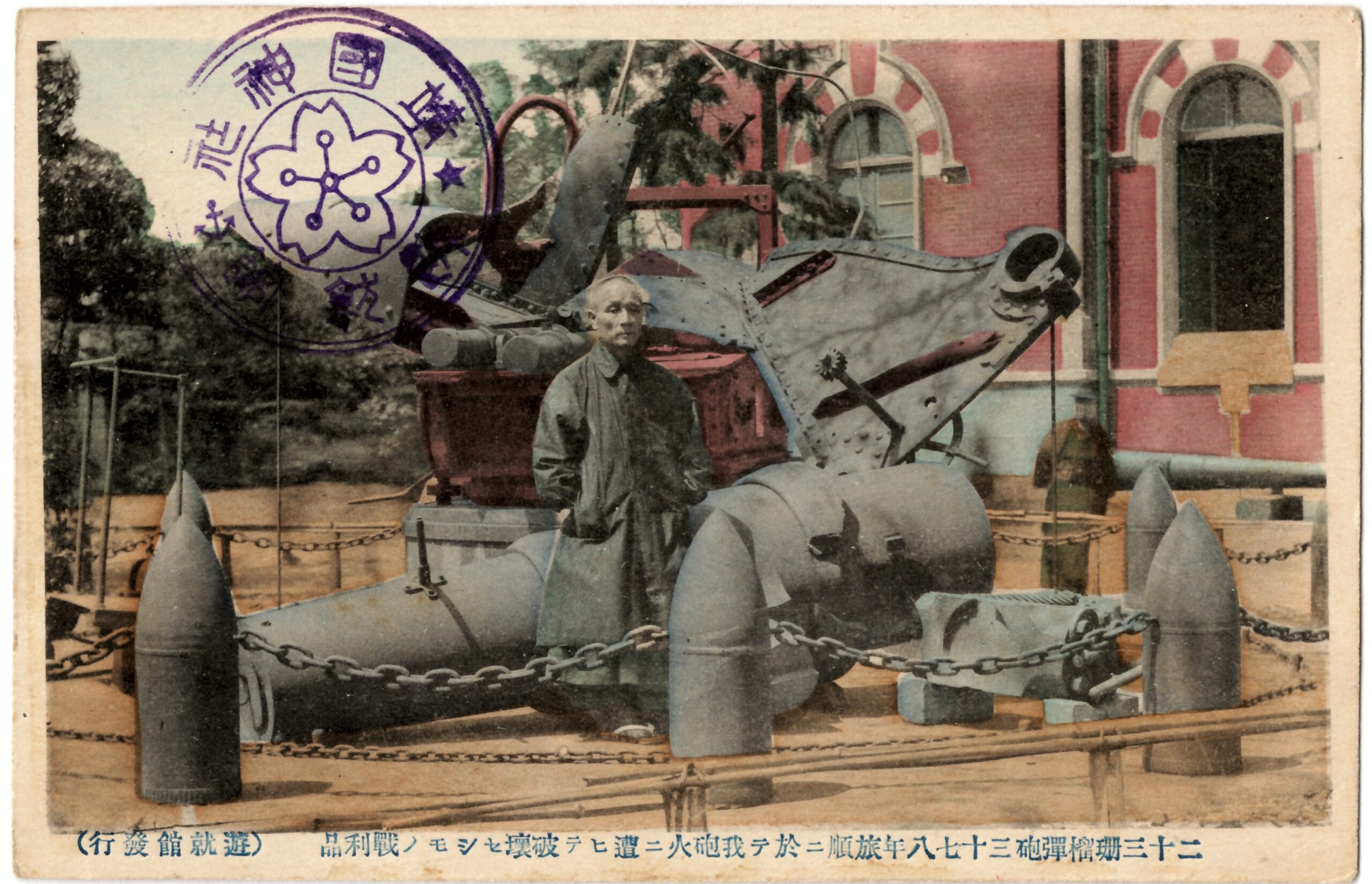

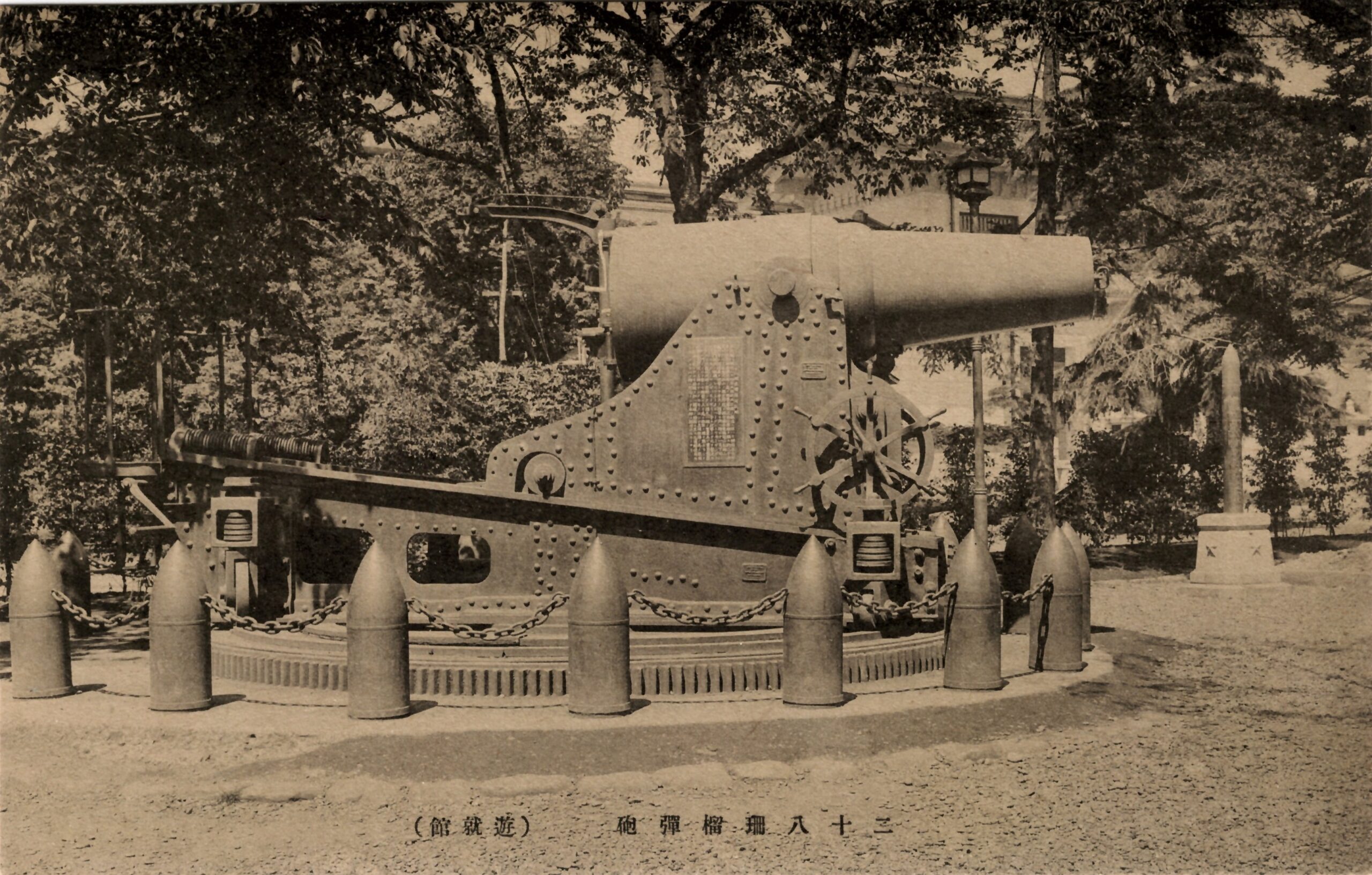

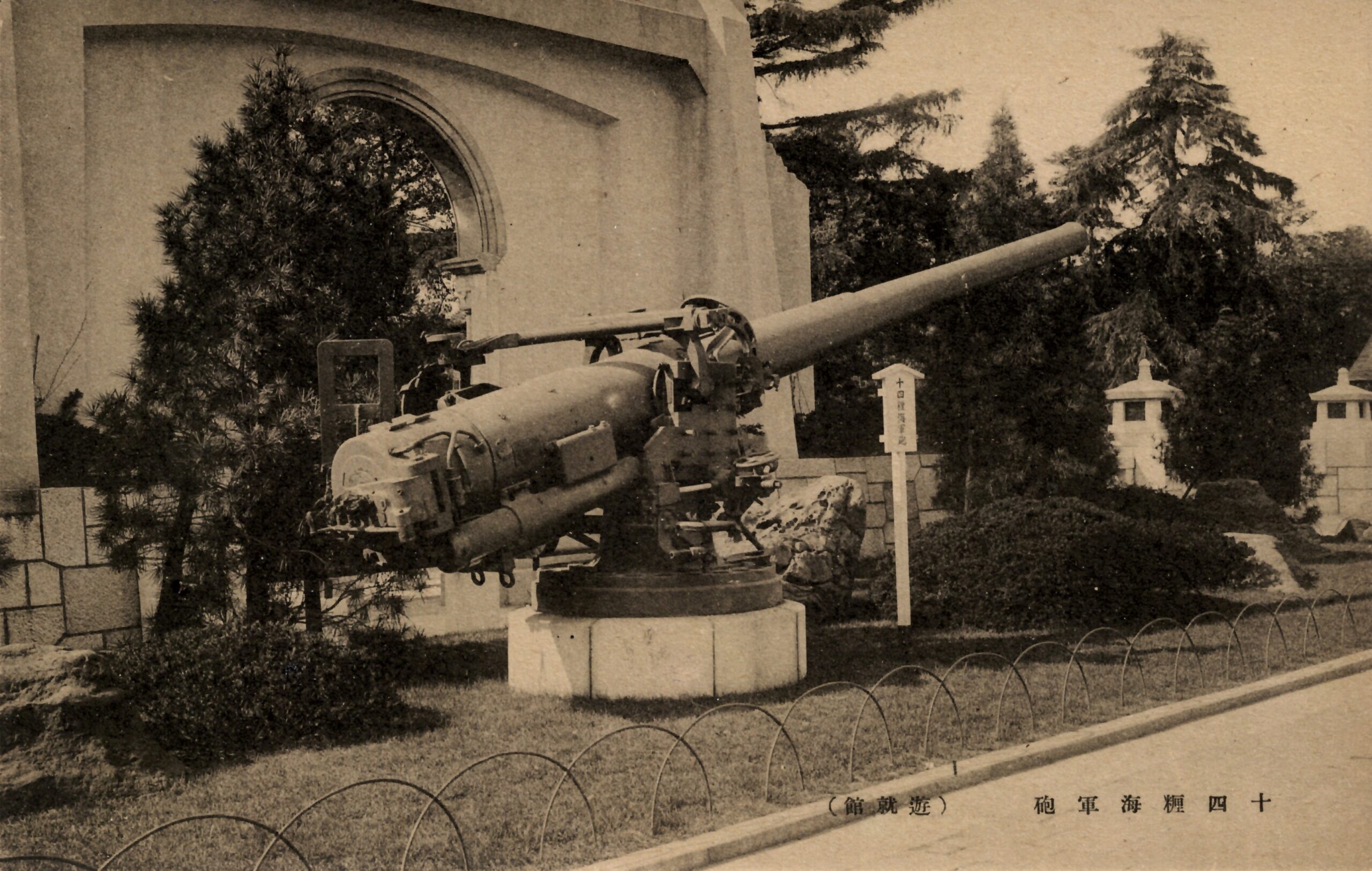

“The brick building to the r. of the temple is the Yūshū-kwan, a Museum of Arms, which is open from 8 A.M. till 5 P.M. in summer, and from 9 to 3 in winter. It well deserves a visit, for the sake of the magnificent specimens of old Japanese swords and scabbards which it contains, as well as armour, old Korean bronze cannon, trophies of the China war of 1894–5, the war with Russia, (1904–5) etc. The 28-centimetre gun outside was manufactured at the Ōsaka arsenal, and used at the siege of Port Arthur for the destruction of the Russian ships; the broken 23-centimetre [11 inch] gun was taken after the capitulation. The numerous portraits of modern military men are depressing specimens of the painter’s handicraft; but a series of large coloured photographs of scenes in the war with Russia merit all praise.”55

Not only was the museum now open daily—since at least 1899—but it contained many more objects related to the conflict with Russia, including modern weapons and colorized photographs.56

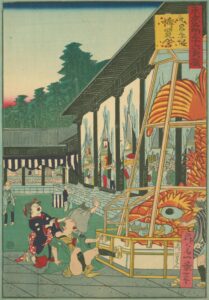

The shifting displays also reflect the gradual change in the Yūshūkan’s role towards becoming at least in part a war museum through the exhibition of conflict. The grounds were filled with trophies from the wars, joined by Ferris wheels and other amusements during special events.57 The popularity of the site and large number of new objects led to a major expansion of the museum in 1908 that saw its exhibition space more than double to over 1900 square meters.58 Cappelletti’s simple building now only formed one side of a much larger quadrangle, with the new rear additions two stories in height, whereas most of the original building only had one floor. The new museum wings were in keeping with Cappelletti’s gothic design.

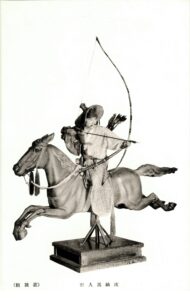

One significant addition to the Yūshūkan collections in the newly expanded facility was a striking set of 14 large format oil paintings by the artist Yada Isshō (1859–1913), which had originally been completed in 1896 and displayed around the country.59 These artworks depicted the thirteenth-century Mongol Invasions that were supposedly repulsed by a combination of Japanese heroism and divine intervention. As Judith Vitale has shown, the Mongol Invasions were an important symbol of Japan’s martial strength and sacred status throughout the early modern period, and they became even more significant from the 1890s onward as Japan again supposedly faced threats from the continent.60 As discussed below in this section, the period during and after the Russo-Japanese War also saw a closer association between the Yūshūkan and the shrine in terms of the religious character of museum displays and the focus on veneration of the fallen. The two institutions were never fully integrated during the imperial period, with the Yūshūkan being established and controlled largely by the Army and directed by a succession of Army officers, while Yasukuni Shrine was managed jointly by the Army, Navy, and Interior Ministry, as it venerated all those who had fallen in the service of the emperor.61

By 1909, the Yūshūkan was officially recording 5–600 daily visitors in springtime and 2–300 per day in the winter.62 The wars with China and especially Russia necessarily transformed the institution from a military museum to more of a war museum focused on the recent conflicts. There was also a significant change in the managerial direction of the Yūshūkan with the retirement of Imamura Nagayoshi (Chōga; 1837–1910), a former army officer and sword expert from Tosa who directed the museum for over 20 years from 1886.63 His influence could be seen in the founding of the Tōken Kanteikai (Sword Appraisal Society) in 1896, which initially met once a month at the Yūshūkan and greatly expanded its activities after 1899.64 The collecting of swords was an integral activity at the museum from a very early stage, initially funded by the second president of Mitsubishi, Iwasaki Yanosuke (1851–1908).65

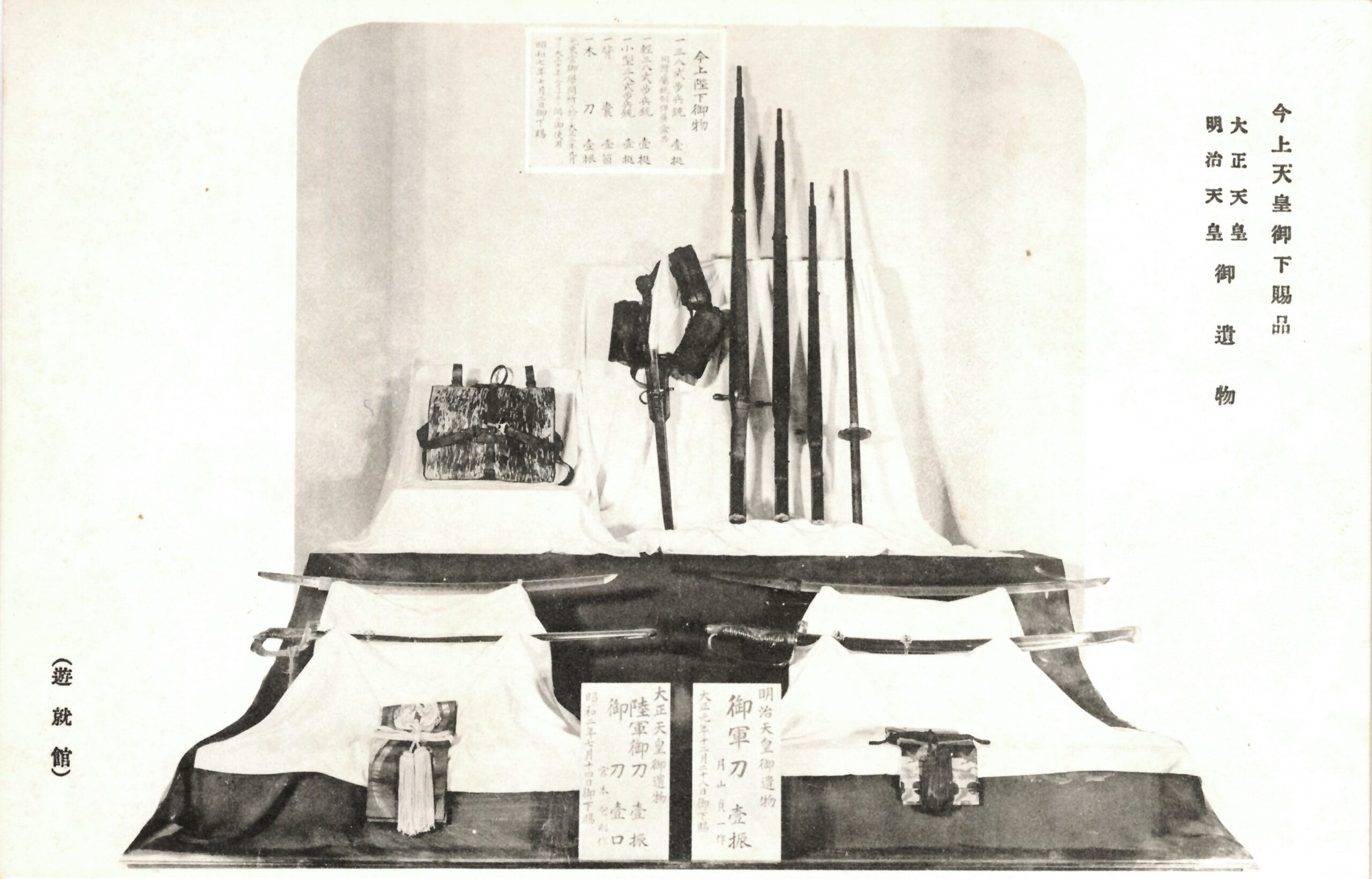

The exhibition approach under Imamura had been relatively conservative in terms of its focus on the items themselves, grouping them by type, but the museum took on a more explicitly pedagogical role along with its increased prominence after the war with Russia. In 1909, oversight of the Yūshūkan moved to a board of directors headed by the famous military surgeon and author Mori Ōgai (Rintarō; 1862–1922). One of Mori’s first steps was to submit a request to overhaul the museum displays to focus on a chronological progression of weaponry, and to emphasize the educational role of the institution. Mori observed that the Yūshūkan did not have a defined role beyond being simply a display space for weapons separate from the shrine without any real connection in terms of management. He wrote to the Army Minister requesting that the Yūshūkan be made an official state institution directly under the control of the Army Ministry. While it would remain superficially attached to the shrine, the museum director would report to the army and manage a team of professional museum staff.66 In 1910, the Meiji emperor issued a decree affirming this new approach at the Yūshūkan, reflecting the growing significance of the site, which by 1919 was being visited by almost half a million people annually.67 Mori himself would more famously become director of the Tokyo Imperial Museum in 1917, where he introduced the same chronological approach to the exhibitions.68

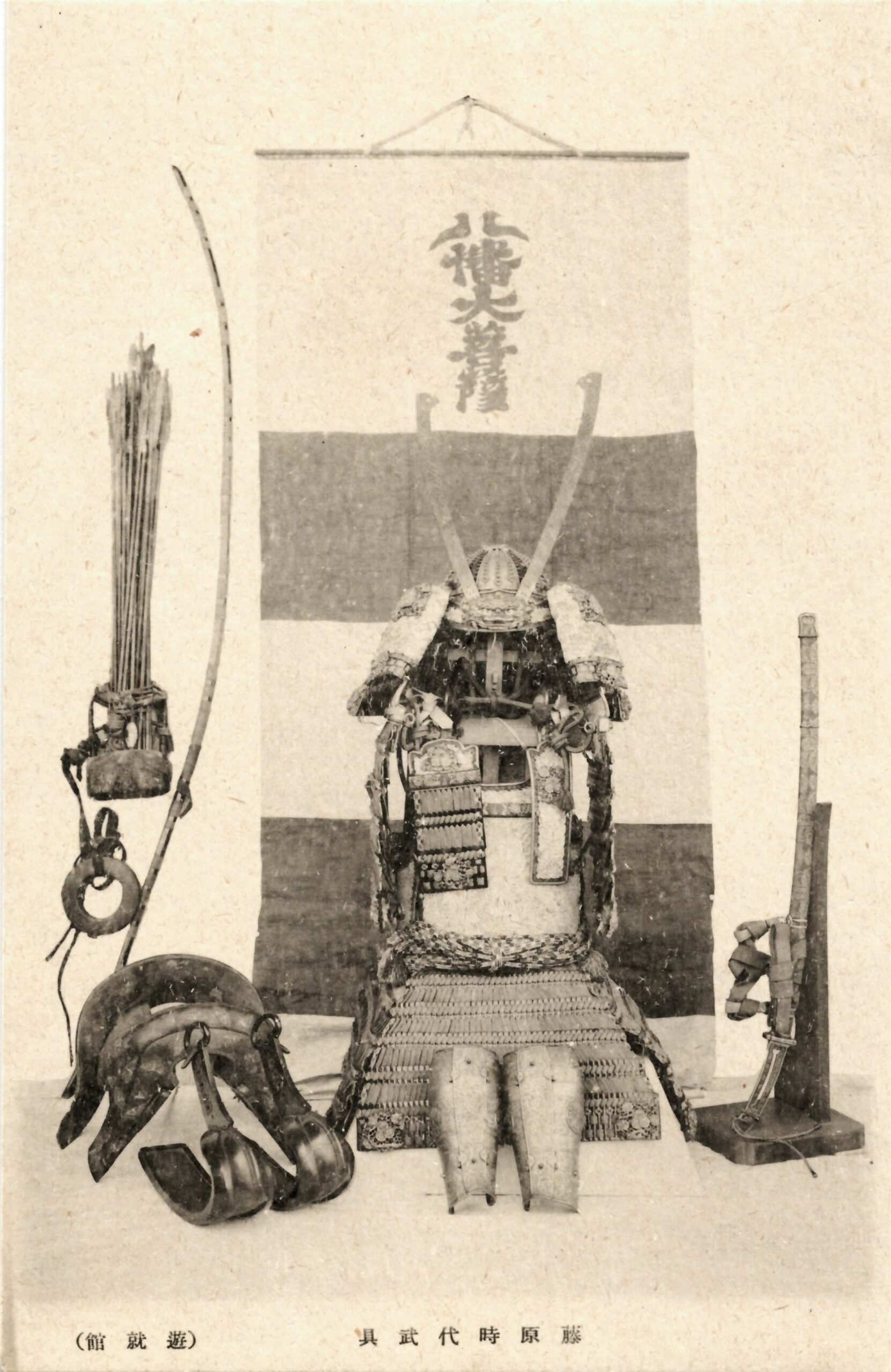

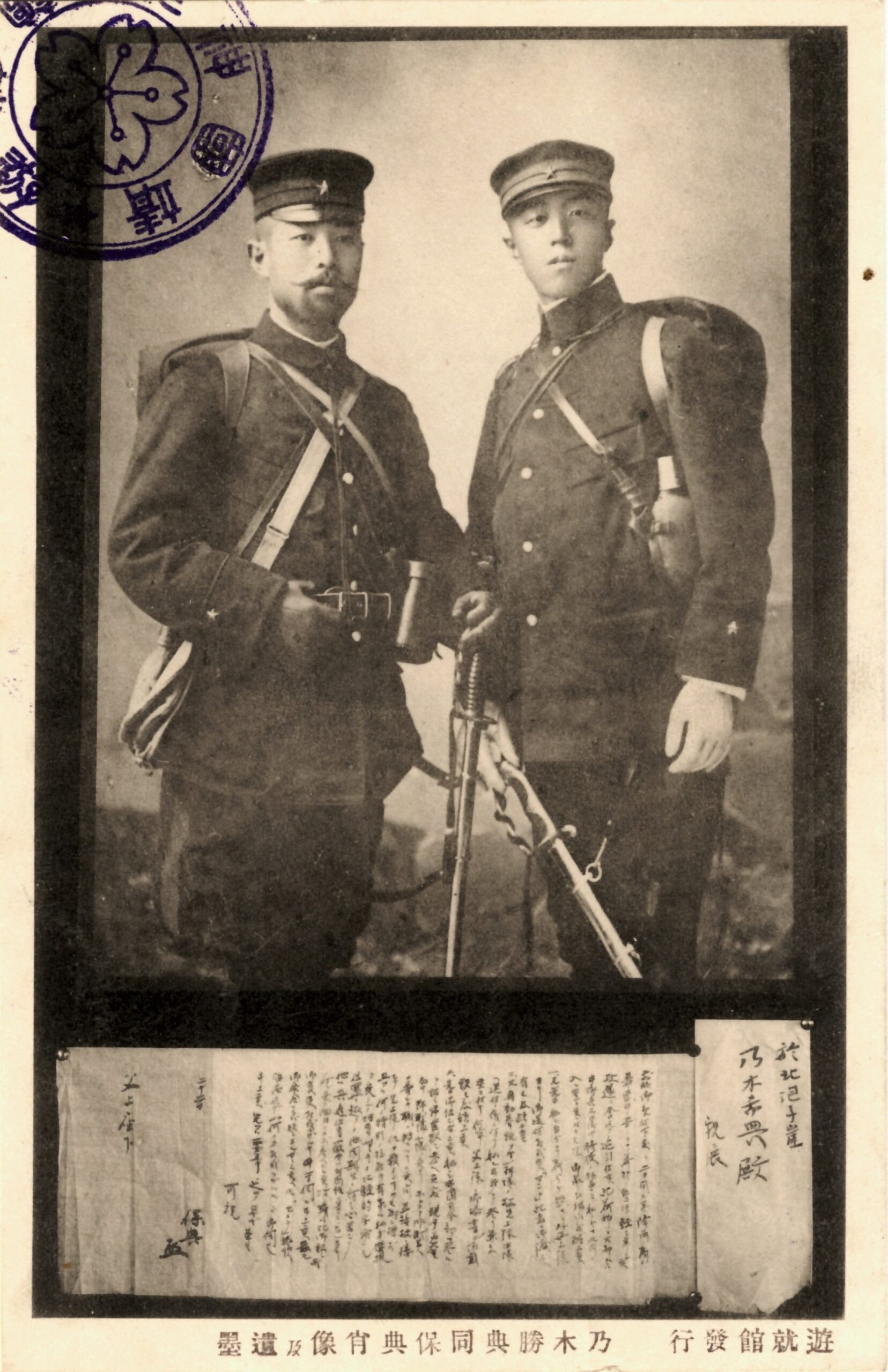

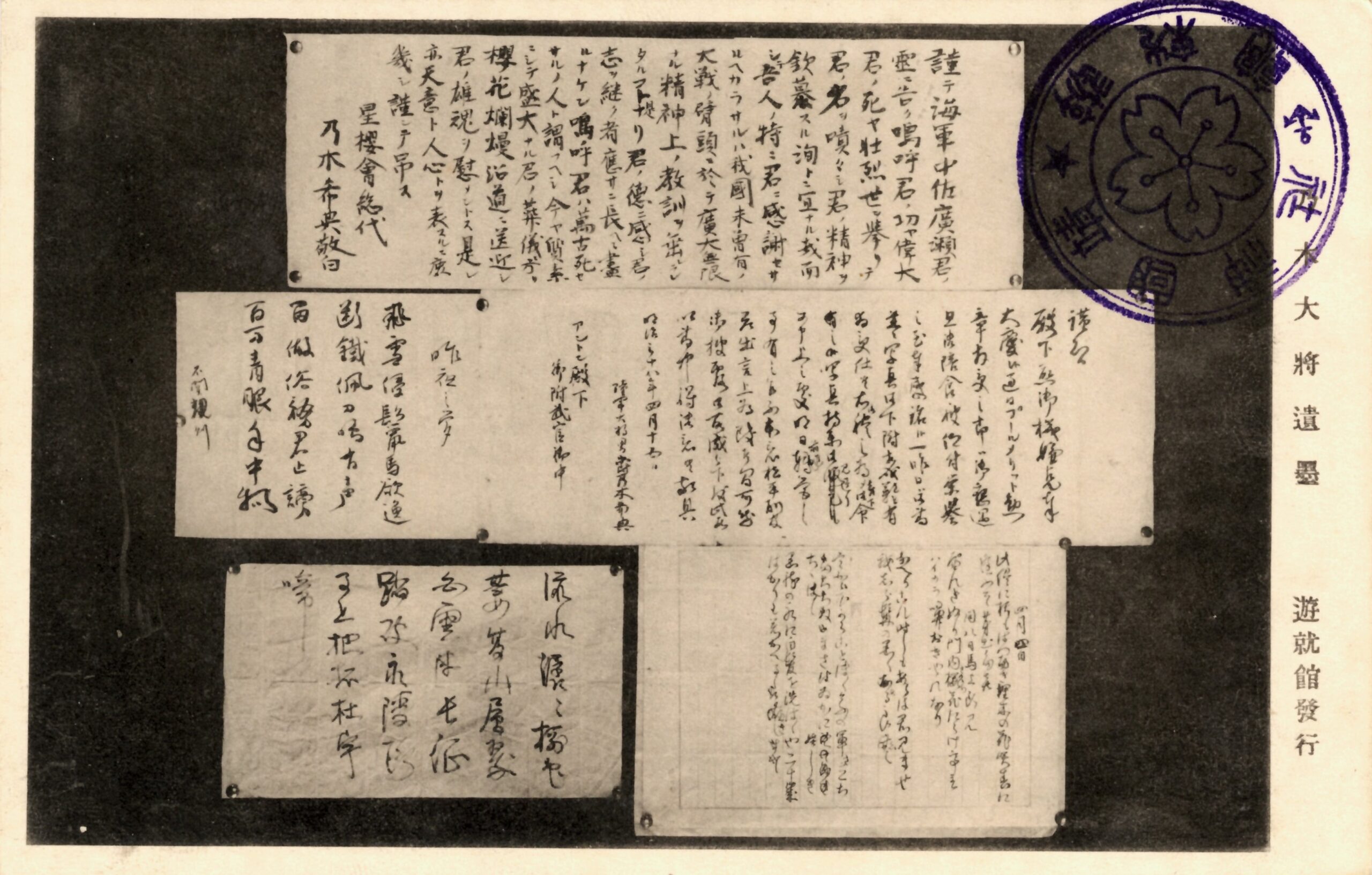

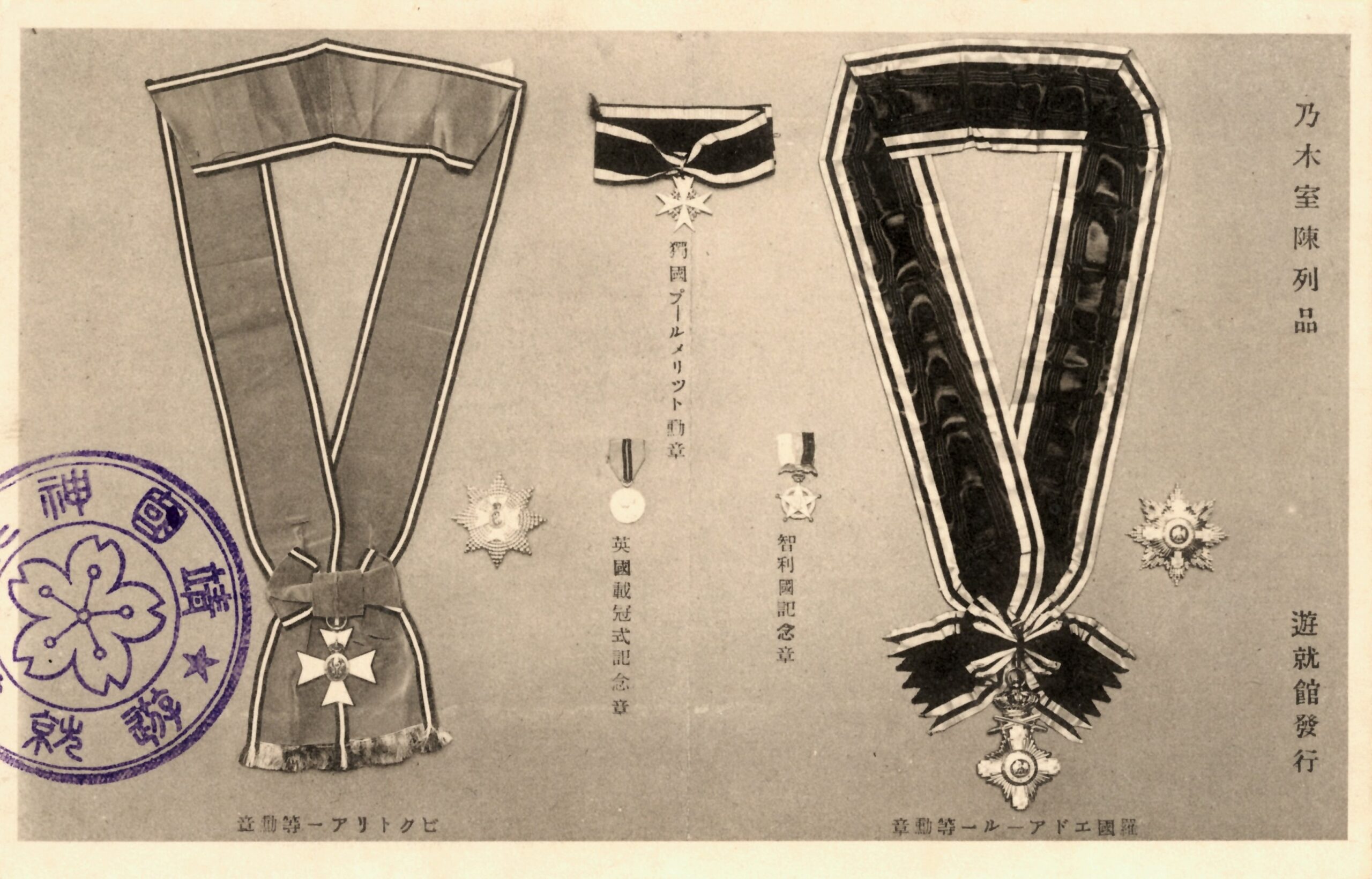

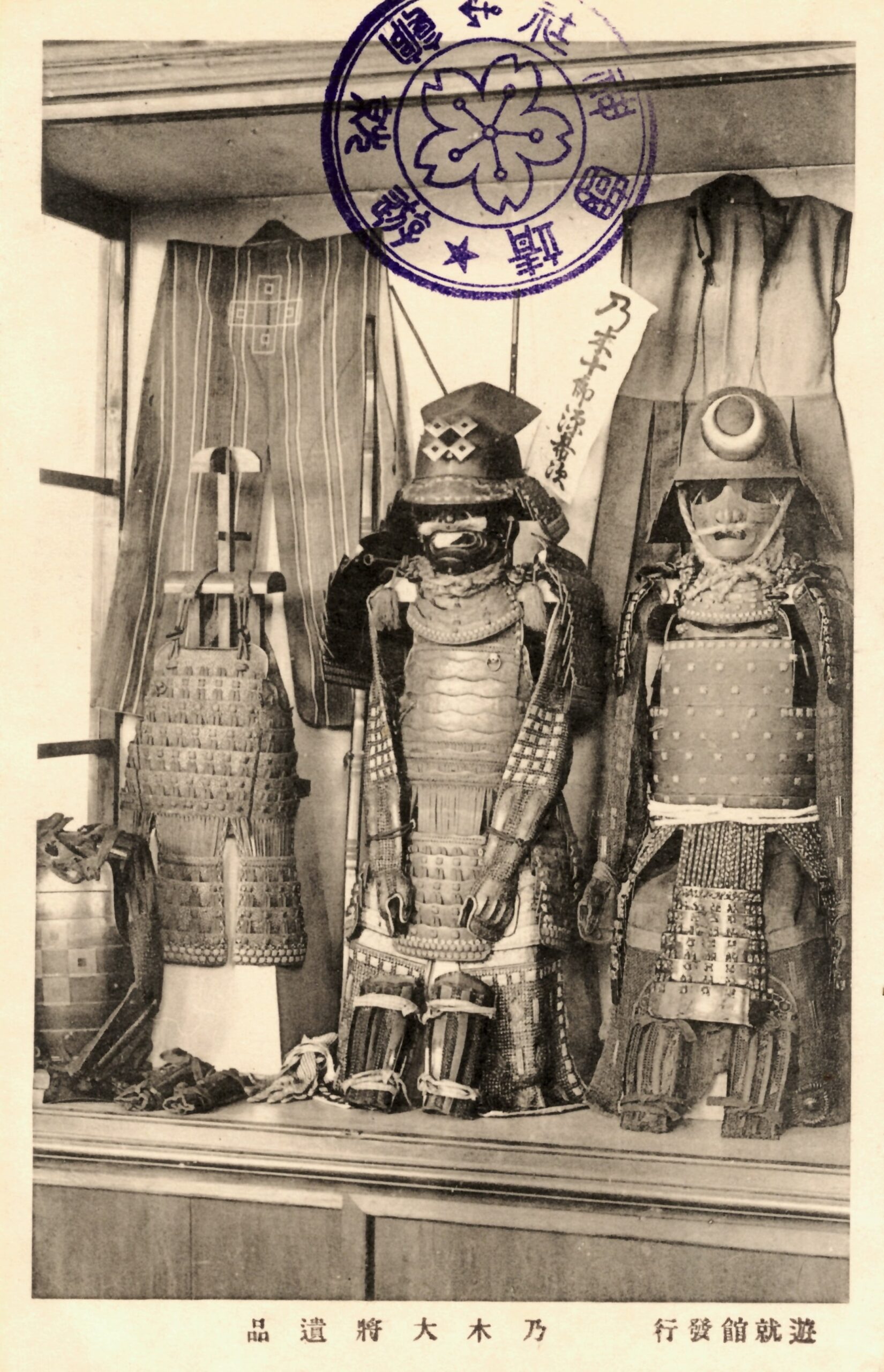

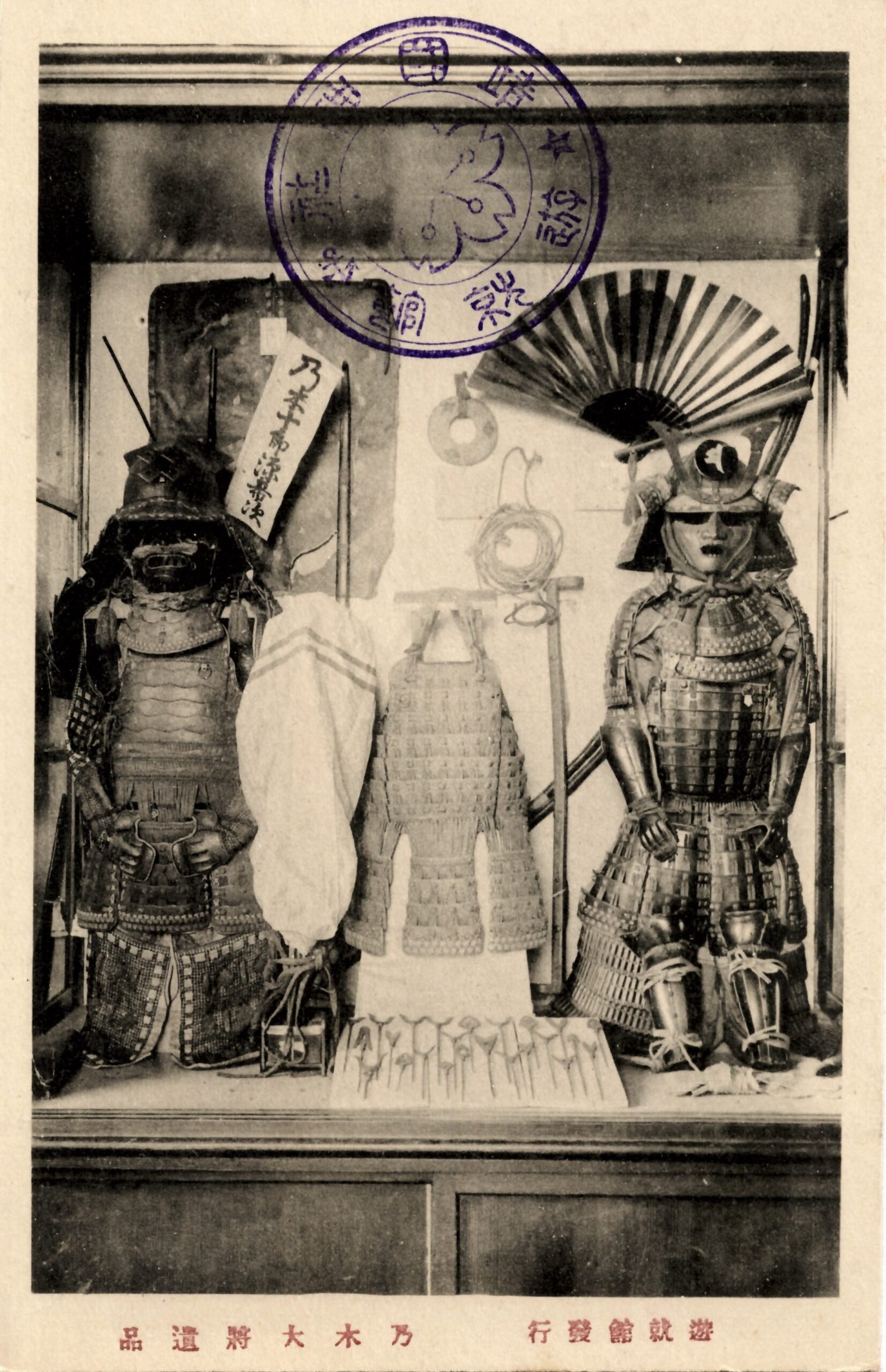

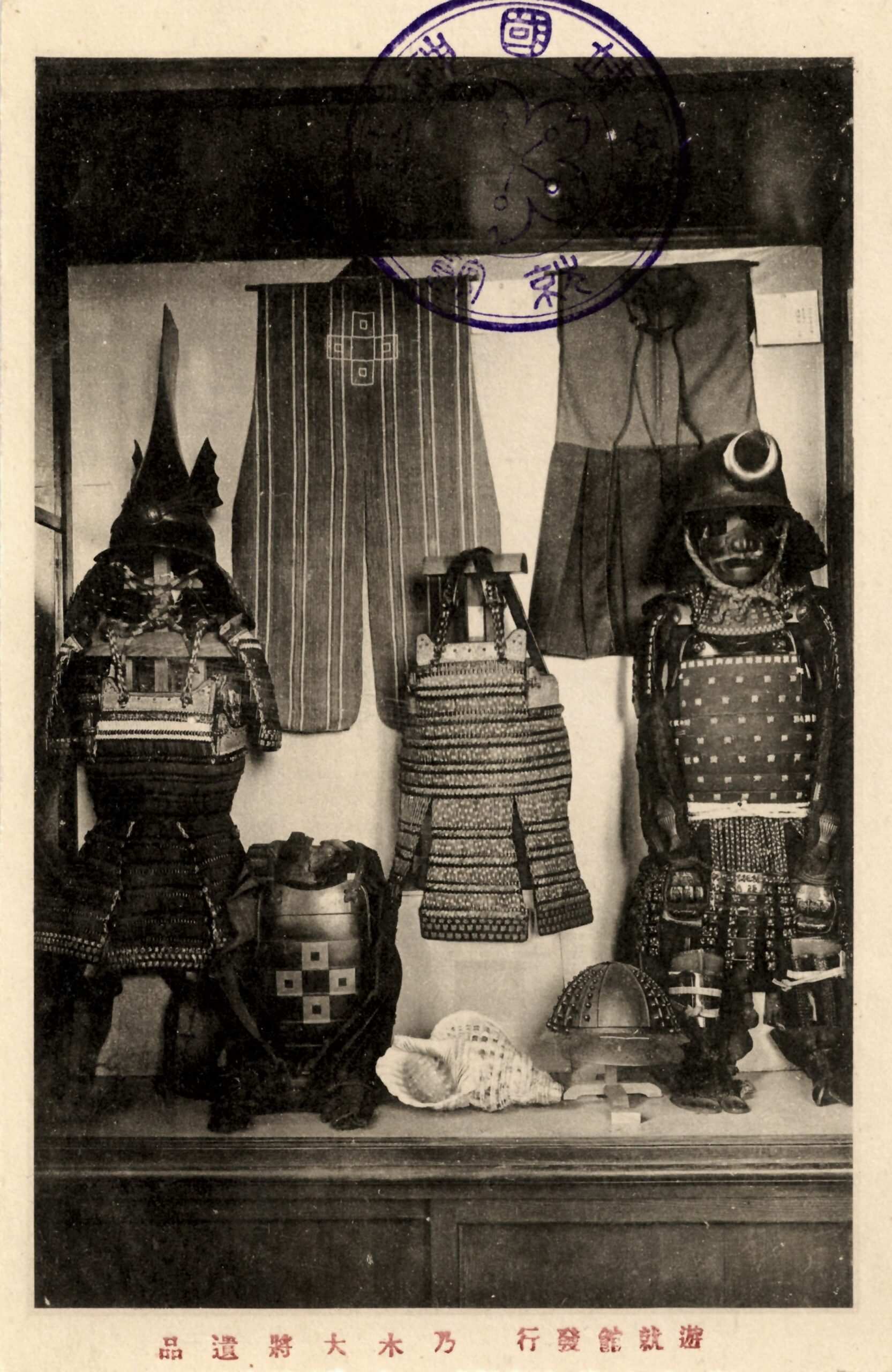

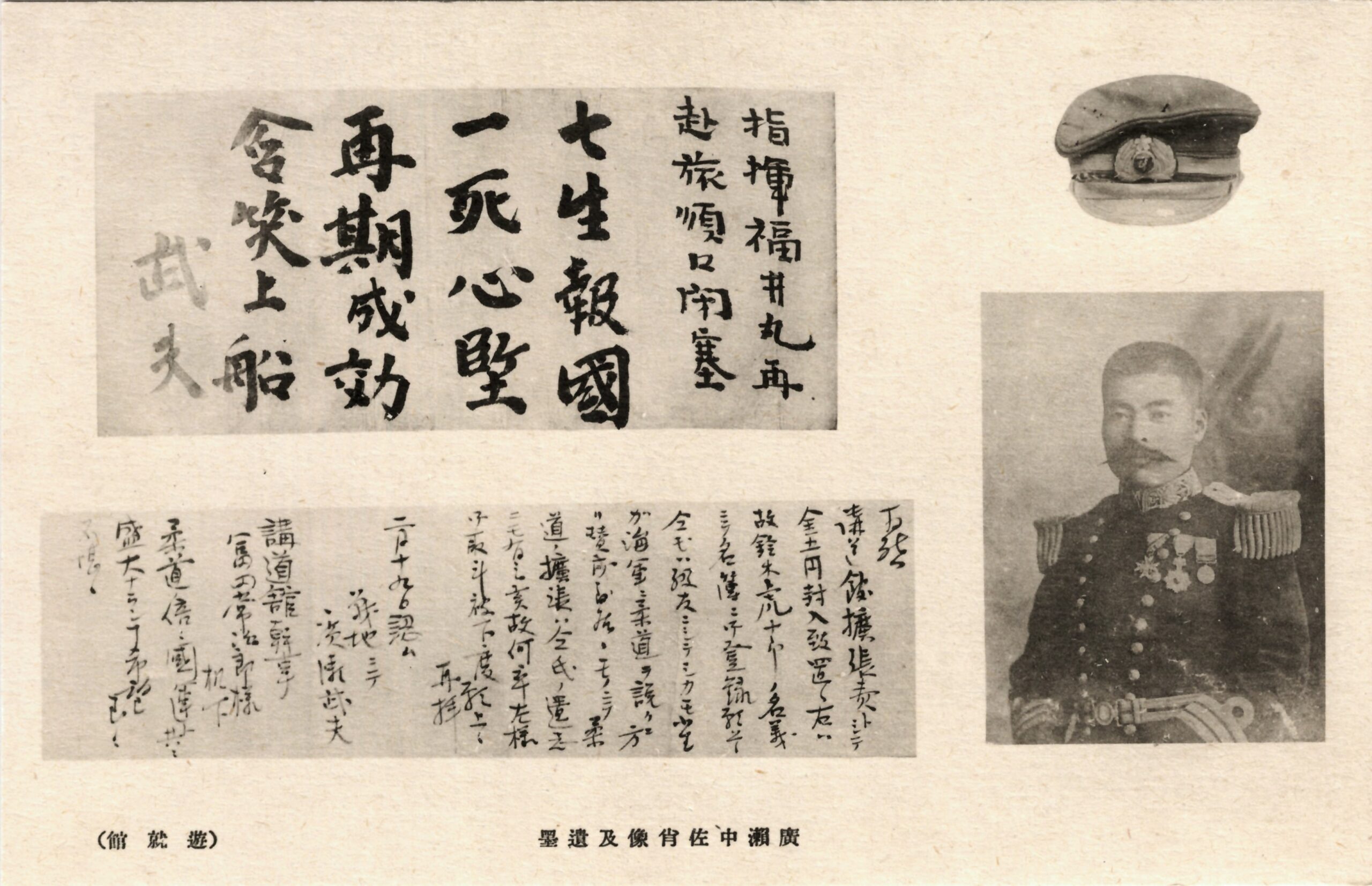

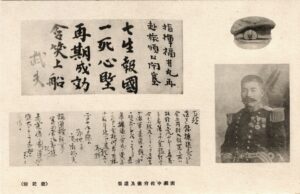

A major event in 1912 fed directly into the Yūshūkan’s new mission for patriotic and militaristic education, when the “Hero of Port Arthur” and “Flower of Bushido” General Nogi Maresuke (1849–1912) and his wife Shizuko (1859–1912) committed ritual suicide on the day of the Meiji emperor’s funeral. This incident sent shockwaves around the world, and cemented Nogi’s prominent status as the embodiment of Japan’s marriage of supposedly traditional samurai virtues with modern military drill. Nogi had himself been involved in education as head of the Peers School, as well as by lending his name to several texts related to samurai ethics. After the Nogis’ death, the couple and their two sons, who both died in the Russo-Japanese War, were frequently used as examples of heroic and patriotic citizens by the Japanese state and military until 1945.69

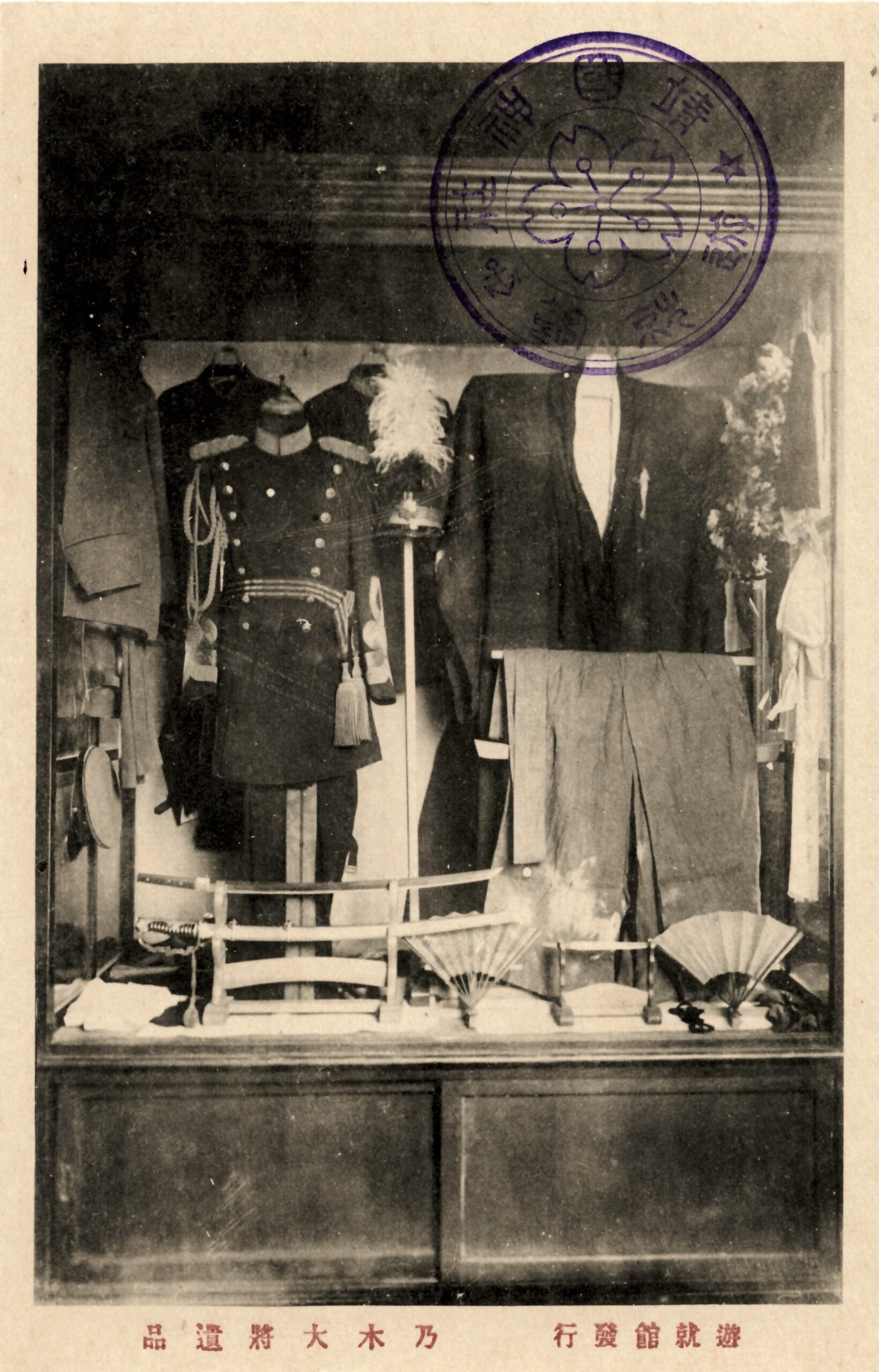

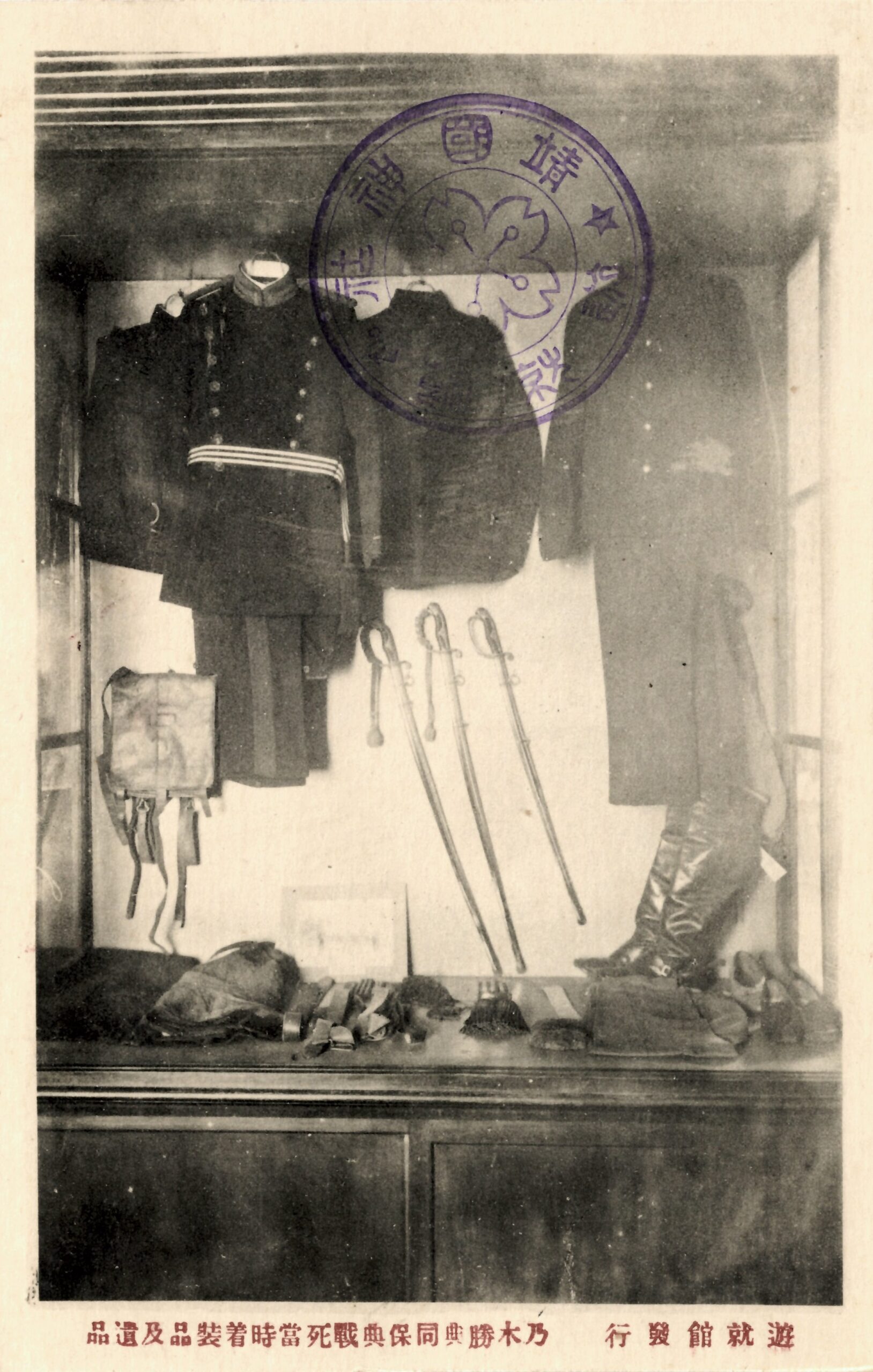

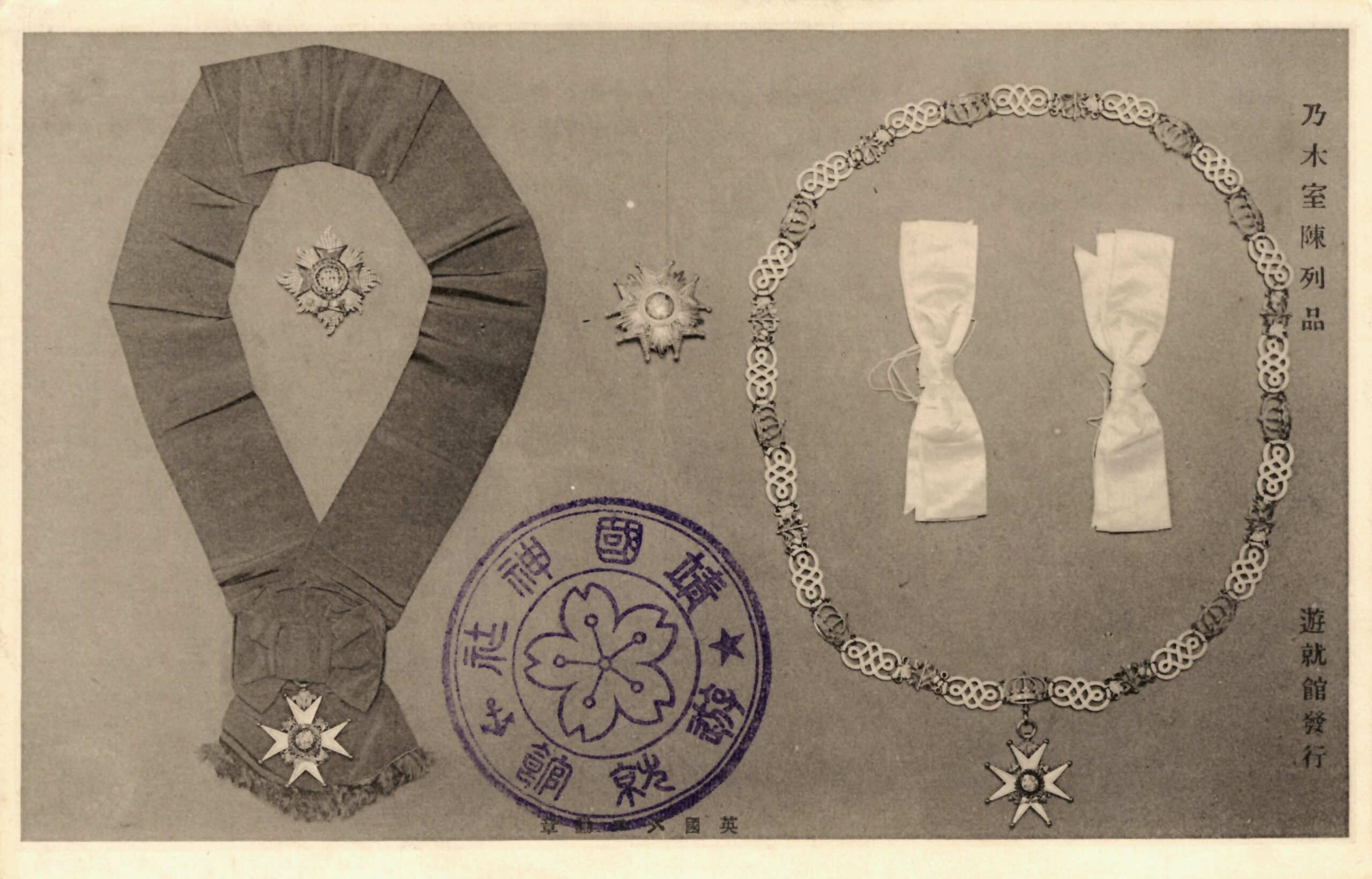

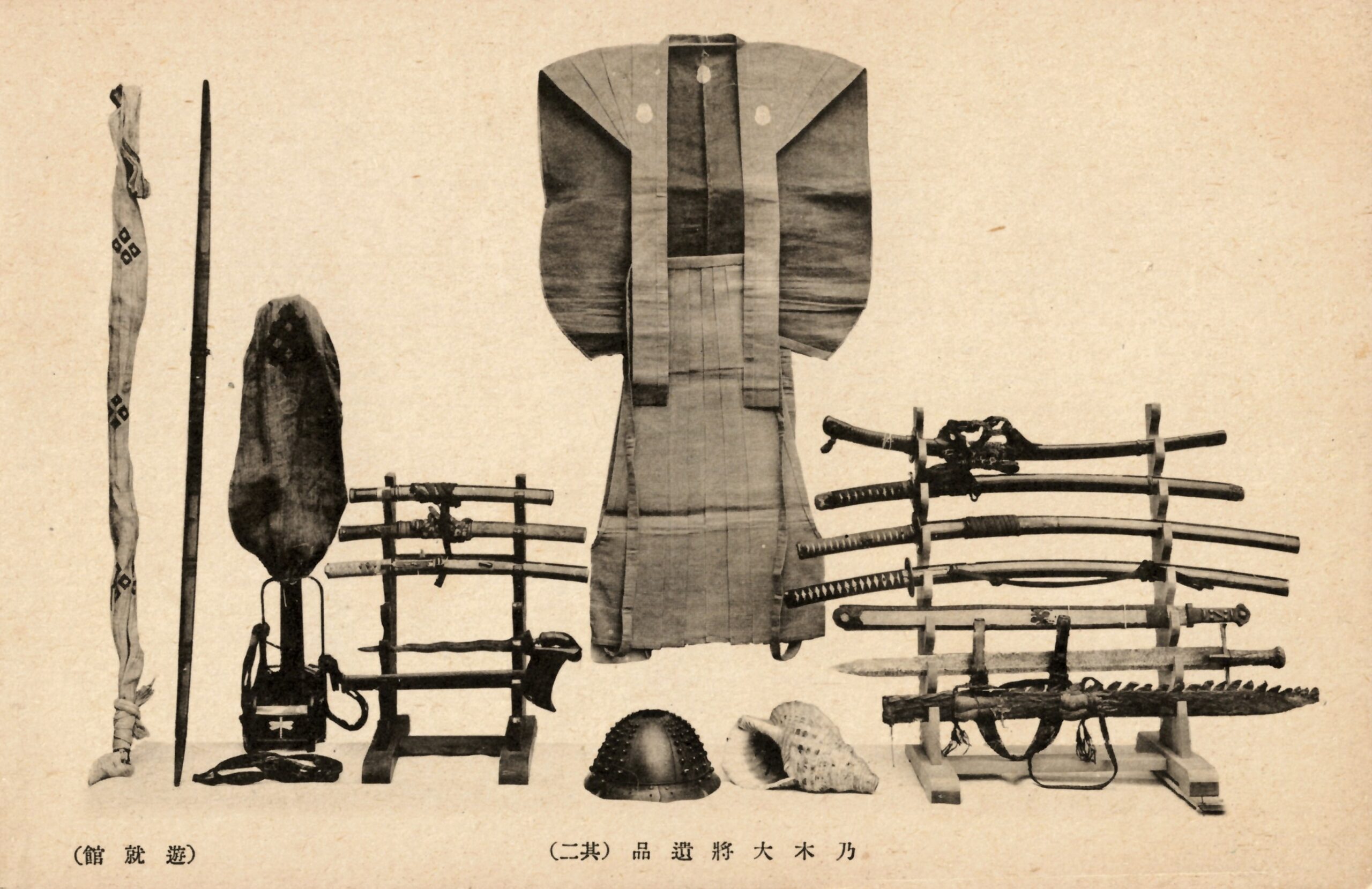

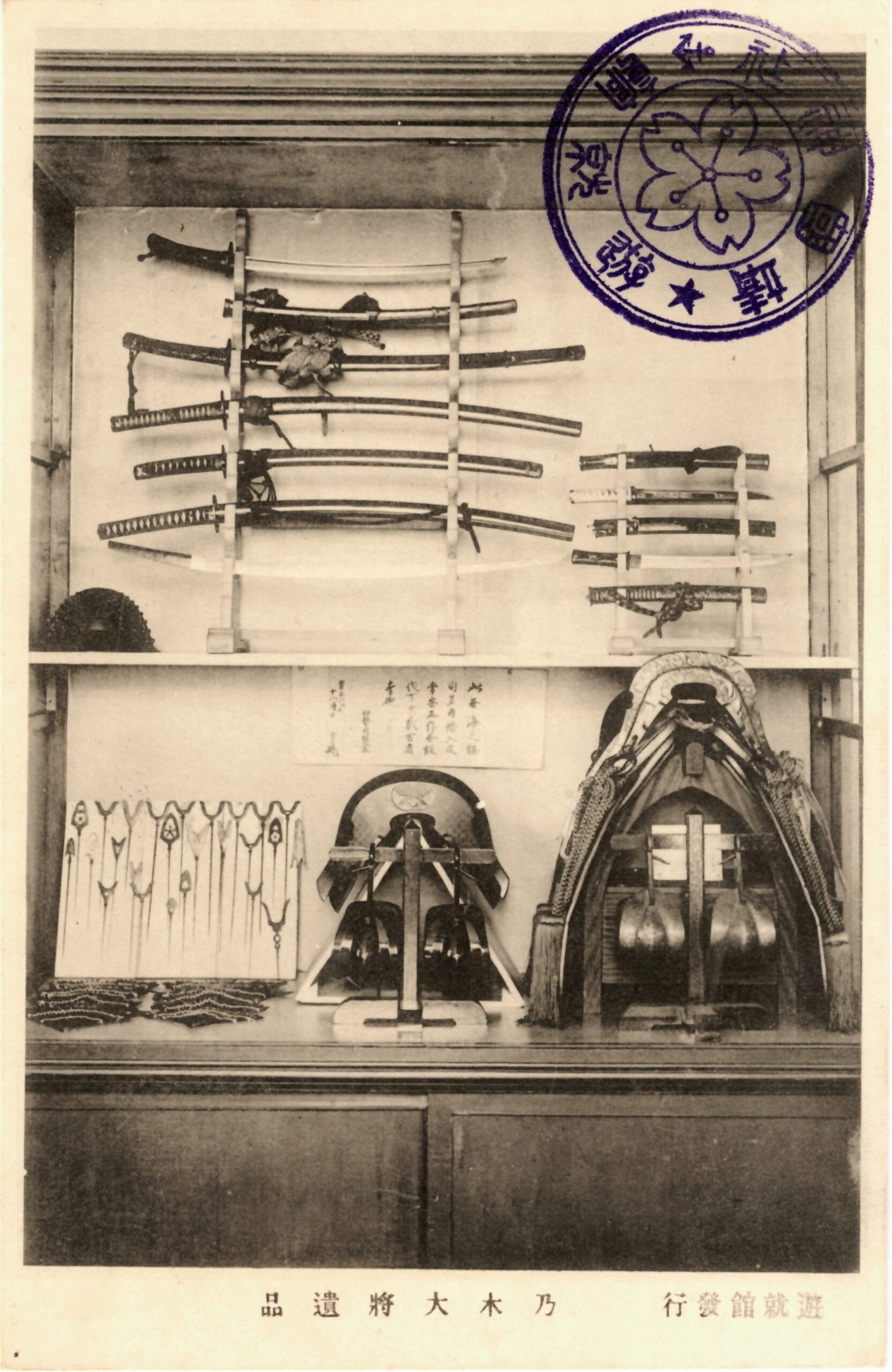

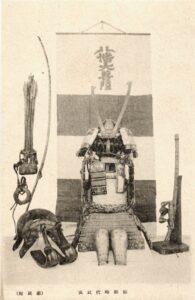

The Nogis’ house in Tokyo eventually became a shrine and major tourist destination, but the Yūshūkan featured prominently in the general’s will. Many of his uniforms and service memorabilia, as well as his collection of samurai swords and armor, were already in the care of the museum and Nogi bequeathed them to the institution.70 The Yūshūkan prominently displayed these objects for the education of the public, and also used them in a wide range of postcards. Significantly, whereas most of the Yūshūkan exhibition displays had been revised into a chronological arrangement that showed the evolution of weaponry and Japanese warfare, Nogi Maresuke’s bequest brought together objects from ancient samurai with those of the contemporary military, thereby contributing to a narrative that Japan’s modern success was based on ancient martial virtues. This narrative gained global currency after the Russo-Japanese War. As the Times of India wrote in response to the general’s death “Belonging by birth to old Japan—he was born in 1849—he yet represented to perfection the finest qualities of modern Japan: he was at once a warrior of the old school and a scientific leader of troops, and the manner of his death suggests that old traditions counted more strongly with him than the ideas he had acquired by the study of foreign civilisations. … He lived and died a samurai.”71

The transition from a military museum to a war museum with a focus on recent conflicts, combined with the high profile of the institution, also posed diplomatic issues. Many of the objects displayed in and around the Yūshūkan were recently captured trophies from the wars with China and Russia. As the Japan Times reported on 13 April 1904, “Two trophies of war obtained during the second attempt to block Port Arthur were delivered yesterday to the Yushukan (Military Museum) at Kudan by the Naval Authorities,” while other articles that spring discussed “Trophies of War in Tokyo” and “Mementos of the Russo-Japanese War.”72 While these objects drew many visitors during the conflict, their status became more complicated as relations with these nations improved after 1905. Kume Kunitake had observed forty years earlier that the taking of trophies by European powers could exacerbate and prolong tensions between those nations, and Japan now found itself in a similar position. The trophies caused little obvious concern among some of the many foreign visitors, such as American sailors or engineers being “shown through rooms of spoils and arms from the Chino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars,” or even envoys from the subjugated Korean court, but they were certainly seen as problematic by Chinese and Russian dignitaries.73

In 1911, the Yūshūkan was drawn into a larger effort to remove Russian objects from exhibits around Japan to avoid offending visitors from the country, reflecting geopolitical shifts.74 In contrast, after Japan’s entry into the First World War, “The trophies of war captured by the Tsingtao besieging army, including 15-centimetre guns and other weapons used by Germans at Tsingtao, will be exhibited for public inspection at the Yushukan (military museum), Kudan from to-day.”75 Significantly less attention was paid to the thoughts of Chinese visitors, however, which is especially striking as the wars with China, Russia, and Germany all took place on Chinese territory. Wang Zhixin provides an overview of prominent Chinese visitors in the first decade of the twentieth century, such as the government official Yang Fu’s (dates unknown) experience at the Yūshūkan, when he was surprised that “weapons from the Russian army and arms from our country are on display for the general public in and around the precinct of the shrine,” while the museum had “many more captured items on display, such as firearms and military uniforms.” These items had been captured in the 1894–5 conflict, as well as the Boxer Rebellion, and Wang describes Yang’s indignation at the contempt shown for China and other nations at the shrine.76

Other Chinese visitors were less critical, and instead saw the military museum as a potential model for China to emulate. The Sichuan governor Lou Liran (dates unknown) described “the Yūshūkan war museum, which houses spoils from the Sino-Japanese War,” including Chinese banners and letters of surrender, while the government official Wang Sangran (dates unknown) recounted old and new weapons, as well as “model reproductions of towns and fortresses where battles took place and also exhibits of small scale models of warships.” Wang Sangran further described “large-scale diagrams of battlefields filled with dense smoke of cannons … the armies confront each other in a microcosm … As visitors look upon the sights before them, a spirit of admiration for bravery and valuing death wells up from within.”77 For Chinese visitors to the Yūshūkan, feelings of humiliation were mixed with a sense that China would benefit from a similar institution, which was one of the secrets to Japan’s military strength. These sentiments echo the complex sentiments towards the ethic of bushido, the “way of the warrior,” felt by Chinese exiles and students in Japan after the Sino-Japanese War, when bushido discourse was at its peak. While some criticized it as an ethic of cruelty, others, such as the reformer Liang Qichao (1873–1929), argued that China needed its own bushido (Ch. wushidao) ethic in order to survive and be successful.78

The Russo-Japanese War had a transformative effect on both Yasukuni Shrine and the Yūshūkan. The museum celebrated Japan’s victories through trophies and dioramas, while the shrine commemorated the terrible number of casualties from the conflict. These two aspects of the shrine-museum complex became ever more closely intertwined, especially as the Yūshūkan expanded and took on a more explicit role in the inculcation of patriotic and militaristic sentiments. At the same time, the nationalism of the period made Cappelletti’s castle seem ever more incongruous. This came to a head during a major overhaul of the shrine grounds in 1915, when the horse racing track was removed, a broad approach avenue created, and countless trees were rearranged, all in order to “clothe the whole precinct with an air of classical sublimity.” Furthermore, the Japan Times reported, “Some device will also be made to cut off the view of the foreign architecture of the Yushukan military museum from the standpoint of the primitive shrine.”79 The removal of the racing track is also significant in that it was not a traditional Japanese-style course, but rather a Western-style oval where the competing riders wore modern military uniforms.80

Amidst the tremendous destruction and loss of life caused by the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake, the damage caused to the Yūshūkan did not warrant extensive mention in the press. Most of the exhibits survived, and there was certainly a degree of ambivalence towards the building itself, as the national and geopolitical environment was very different than at the time of its construction forty years earlier. An official report on the earthquake mentioned that the parapets at the top of the building were strongly affected, with one third of them having collapsed and a further third displaced. The report suggested that the building would probably have to be torn down as not only were the decorative elements severely damaged, but the bond between the bricks was dangerously weakened.81 The main gate was ultimately preserved as the backdrop to a gun display, but the rest of the museum was razed and replaced by a temporary structure with over 1600 square meters of display space, which opened on 1 August 1924.82

The history of the Yūshūkan in the decade after 1923 is also significant with regard to the shifting role of the military in society. The idea that the 1920s were characterized by “Taisho democracy” has long been a subject of debate, and the period included important developments such as Japan’s active involvement in the League of Nations and the extension of universal manhood suffrage in 1925, while the military was negatively affected by hostility to the quagmire of the Siberian Intervention of 1918–22. Cuts to military budgets in the 1920s, as well as much more urgent reconstruction projects in Tokyo following the earthquake, also contributed to the Yūshūkan remaining without a permanent home until the 1930s. At the same time, the military retained and even raised its public profile in other ways, and I have argued elsewhere for a culture of “Taisho militarism” that persisted throughout this period.83 Paul Barclay has applied the concept of the “forever war” to Imperial Japan between 1894–1945, and the Yūshūkan was an important site for the idealization of Japan’s longer martial heritage.84 This is reflected in the number of visitors to the Yūshūkan even in its temporary building, exceeding 300,000 annually by the end of the 1920s.85 The partial transformation of the Yūshūkan into a war museum following the Russo-Japanese War was key to its sustained popularity into the 1930s, as the many veterans, their children, and other relations visited the shrine and museum to venerate the fallen and commemorate Japan’s greatest military victory.

The Yūshūkan and the Fifteen-Year War

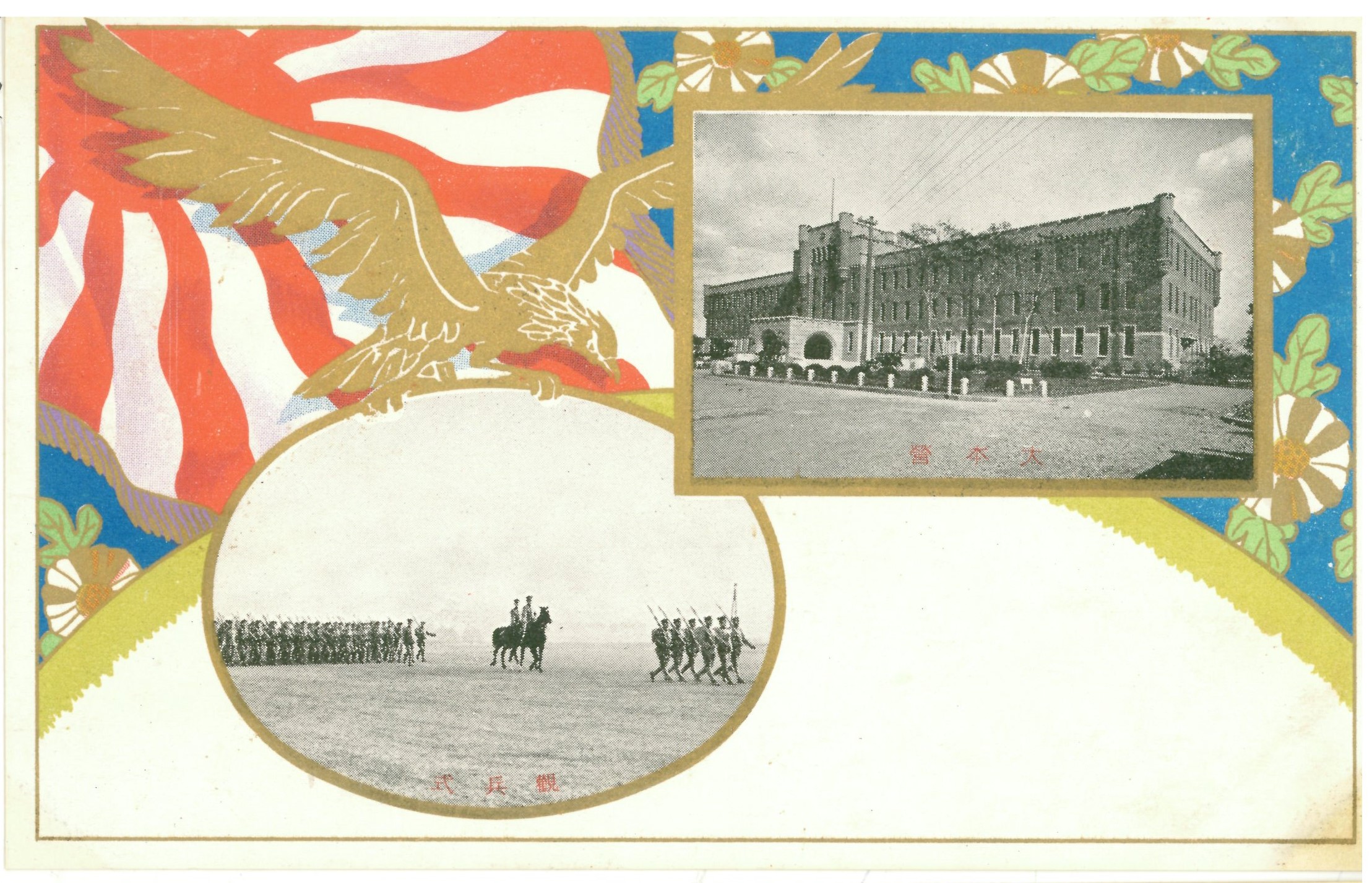

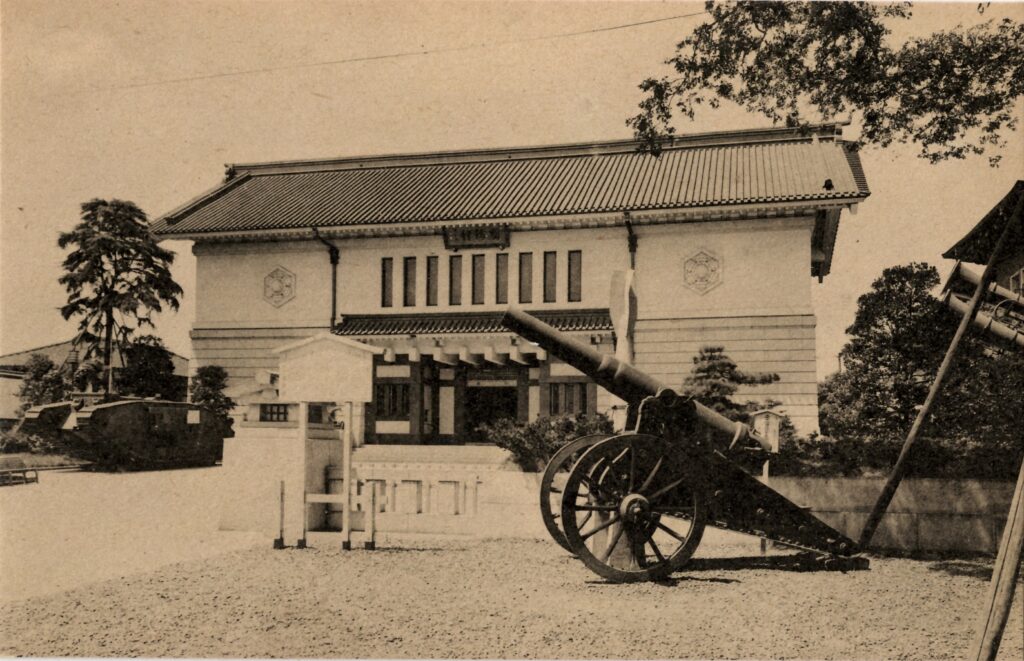

Fifty years after it was first built, the Yūshūkan began to take shape again, this time in a Japanese design much more suited to the environment of Yasukuni Shrine in the 1930s. Once again, the military was the driving force. If Cappelletti’s design was realized by Lieutenant Nakamura Shin’ichirō in the 1880s, the reconstruction was carried out by army engineers under the nominal supervision of the famous architect Itō Chūta (1867–1954).86 The new Yūshūkan that was completed in 1931 again echoed developments at the Tokyo Imperial Museum—also seriously damaged in 1923—as both were executed in the Imperial Crown style, with a curving Japanese roof atop a monumental steel-reinforced concrete building.87 While the choice of architecture for the Yūshūkan was similar to that of the secular Imperial Museum at Ueno, it also reflected the much deeper relationship between the shrine and the military museum, and it would have been unthinkable to recreate a Western-style structure at Yasukuni by the 1920s.

At the same time, as the Yūshūkan was nearing completion, the Imperial Japanese Army was building a new 4th Division Headquarters at Osaka Castle, and this structure was executed in the European gothic style strongly reminiscent of Cappelletti’s museum, but in concrete.88 This suggests that the army was not entirely opposed to foreign designs at the time, even if they would have been considered entirely unsuitable to the area around Yasukuni, as had been foreshadowed by the attempts to hide the Yūshūkan in 1915.

If the period of the Russo-Japanese War represented a shift in the Yūshūkan from a military museum to a war museum, the interwar decades can be seen as a gradual retreat back to the former role. Japan’s involvement in both the First World War and subsequent Siberian Intervention was much smaller in scale than the 1904–5 conflict, which continued to dominate the modern exhibits and narratives in the Yūshūkan. In this way, as the Russo-Japanese War moved further into the realm of history, it became integrated into the evolution of weapons and warfare that characterized the museum exhibition. At the same time, the conflict with Russia continued to be the most important reservoir of heroic figures such as General Nogi, Admiral Togō Heihachirō (1848–1934), Commander Hirose Takeo (1868–1904), and others. As Naoko Shimazu has shown, the Russo-Japanese War was a key reference point and widely celebrated until the early 1930s.89 Even if the men who served in the war were no longer active—and perhaps this fact contributed to idealistic portrayals of the war—many senior military figures in the 1930s and beyond would themselves have been inspired by the unprecedented celebratory media surrounding the war in their formative years.

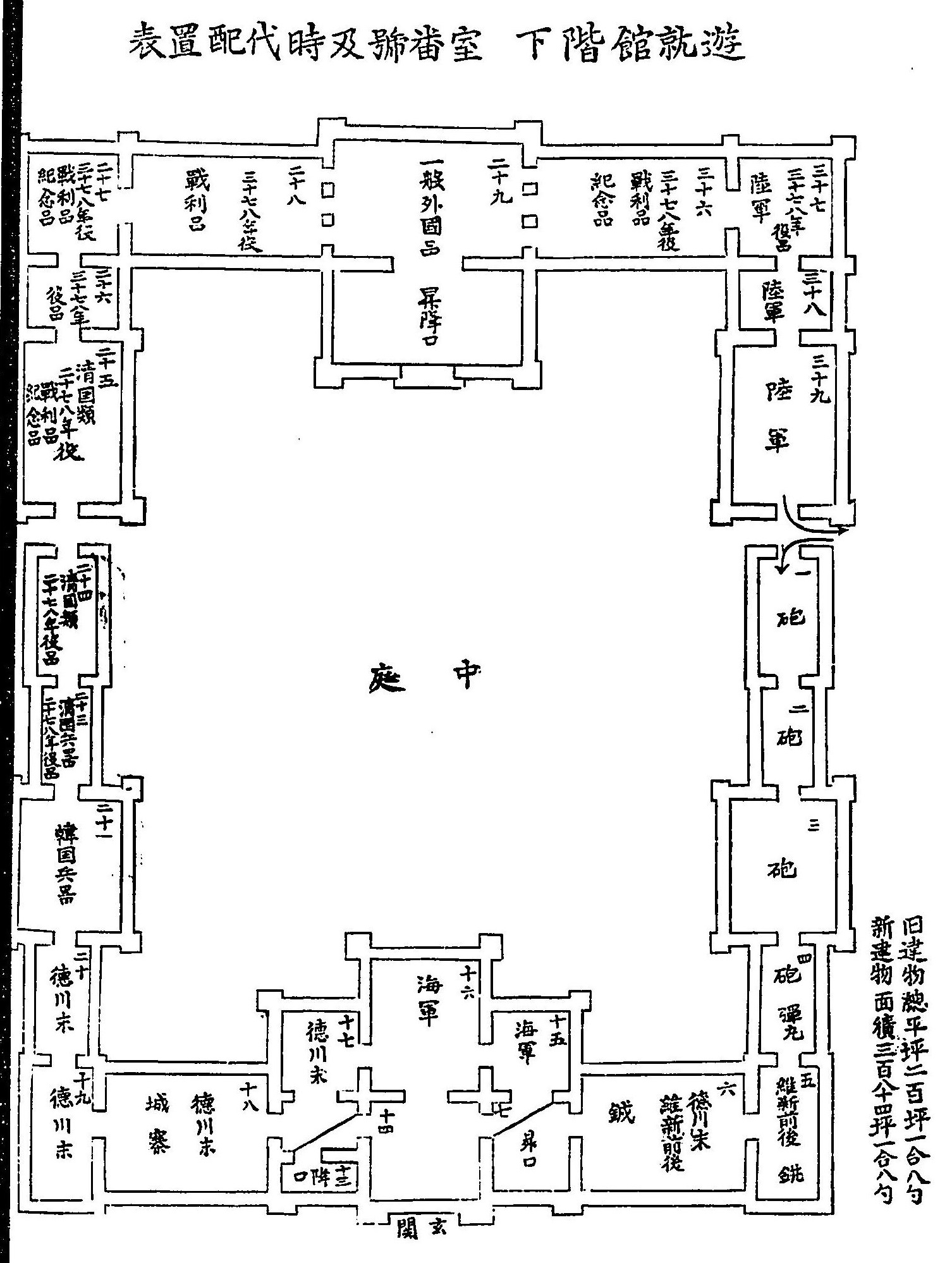

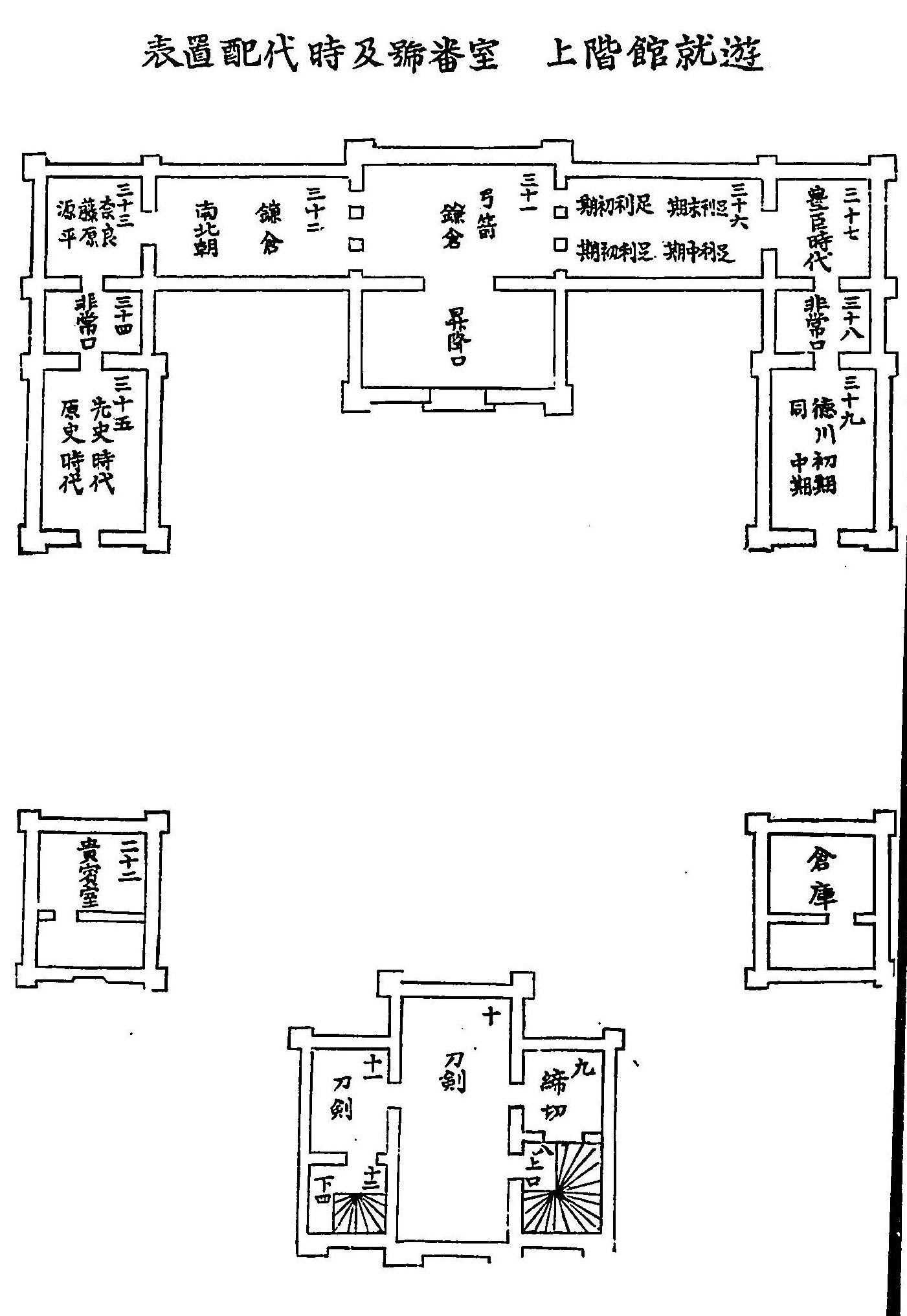

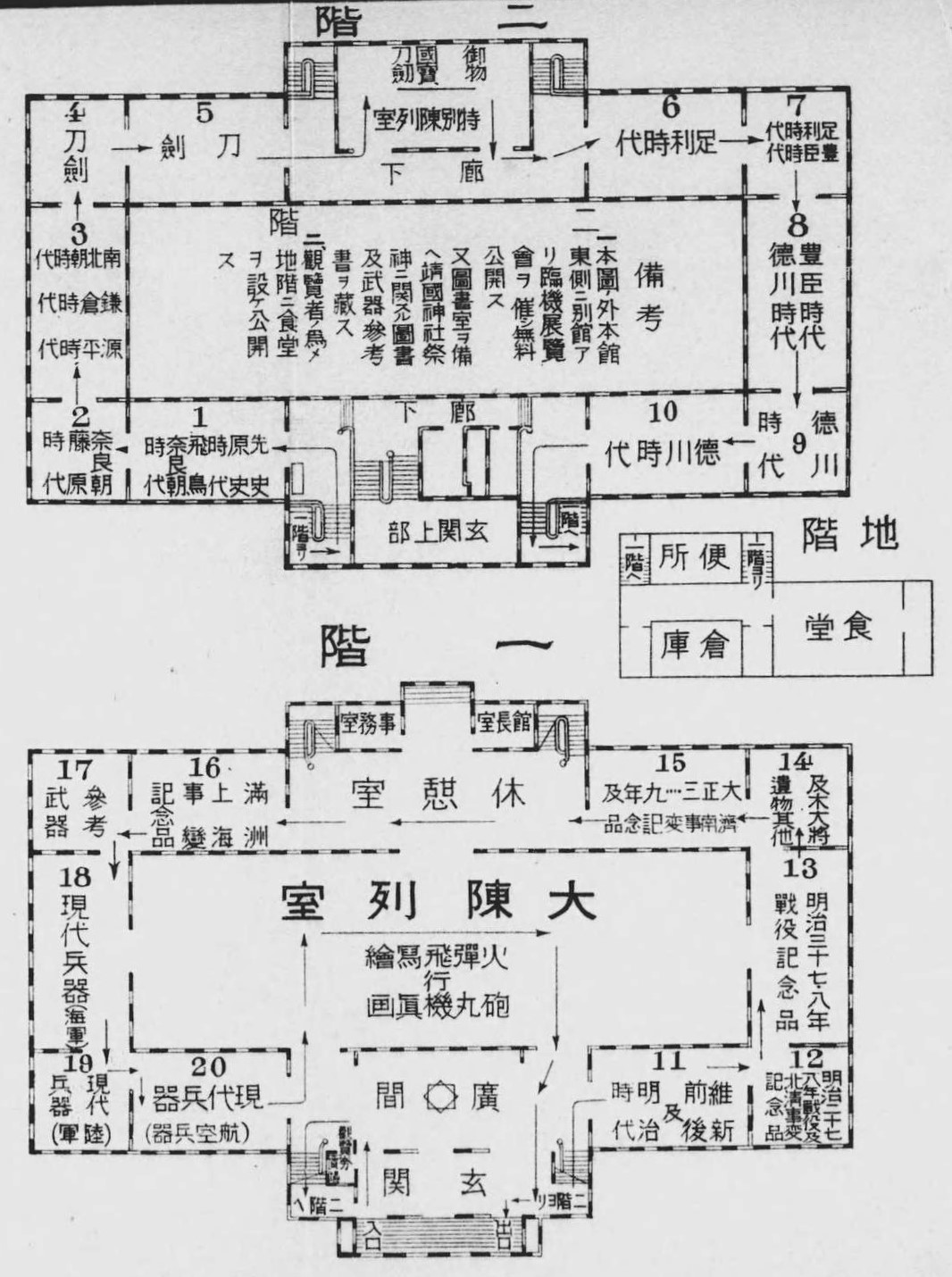

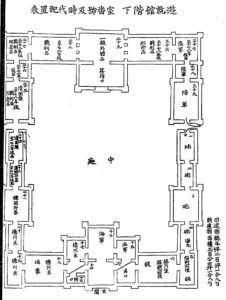

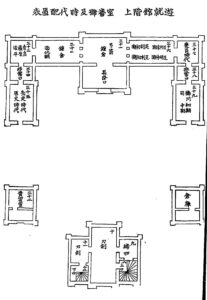

As a result, the new Yūshūkan was presented with a problem almost as soon as it was completed in 1931. In some quarters in the 1920s, there was hope for peaceful internationalism and engagement with the League of Nations as the government implemented military retrenchments. At the same time, militaristic ideals and symbolism remained prominent in Japanese culture and society throughout the period, reflecting the dynamics of “Taishō militarism.” Just as the Yūshūkan was being completed, the Manchurian Incident seemingly confirmed that war would not merely be a thing of the past. The already high number of visitors to the museum rose even further, while summer opening hours were extended to 9pm to meet demand.90 Even in 1929, when the museum was still in temporary accommodation, it was the most-visited attraction in Tokyo, and possibly Japan, after the Ueno Zoo, and comfortably ahead of the Imperial Museum.91 The emperor’s visit to the new permanent building was a major event, and a great number of objects were donated for display.92 The chronological arrangement of objects was in keeping with Mori’s reform, with visitors entering and ascending to the second floor to start their tour with items from prehistory until the end of the Tokugawa period, before returning to the ground floor to walk through displays of Japan’s modern wars and a room dedicated to Nogi Maresuke.93

The tremendous popular interest was both met and stoked by a massive expansion of the Yūshūkan’s activity in loaning out objects across Japan for local exhibits at schools, department stores, newspapers, prefectural authorities, regiments, and other venues and organizations.94 The number of visitors were carefully recorded in the annual reports, and these displays reached many millions of people over the course of the 1930s and early 1940s. Certain exhibits were especially popular, such as one on Manchukuo that drew 107,181 visitors to the Yūshūkan in April and May of 1934, while the 30th anniversary of the Russo-Japanese War in March that year attracted 76,000 people.95 With regard to the many traveling exhibits, an article in the Japan Chronicle titled “Military Museum: Articles on Show Range from Armour to Machine-Guns” provides a sense of one installation in 1938:

“With a view to contributing to the national spiritual mobilization movement, the Yushukan (Military Museum) belonging to the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo is to hold a special exhibition of various weapons, trophies and war paintings etc. at the Nankai Takashimaya Department Store in Osaka from January 3rd to 16th. The event is supported by the Fourth Division headquarters, and the Osaka Naval Supervising Office. The articles to be displayed include suits of armour and swords of olden days, lances used by the Cossacks in the Russo-Japanese War, a bed used by the Russian Commander-Chief in the Russo-Japanese War, which was used by the late Field-Marshal Oyama, the Japanese Commander-in-Chief in the same war, the blood-soaked carpet found in the room where the late General Nogi died (committed hara-kiri) with the Emperor Meiji, and up-to-date Czechoslovakian light machine-guns.”96

The article makes clear that various key elements of the Yūshūkan’s collections were brought together in the exhibit, including samurai armor and swords, as well as trophies from the Russo-Japanese War, macabre mementos of Nogi Maresuke, and the latest military technology, which could also be from overseas. Furthermore, this exhibition shows the close interplay between the military, which sponsored the exhibition, the Yūshūkan, which provided the objects, and the private sector, in this case the venerable Takashimaya Department Store.

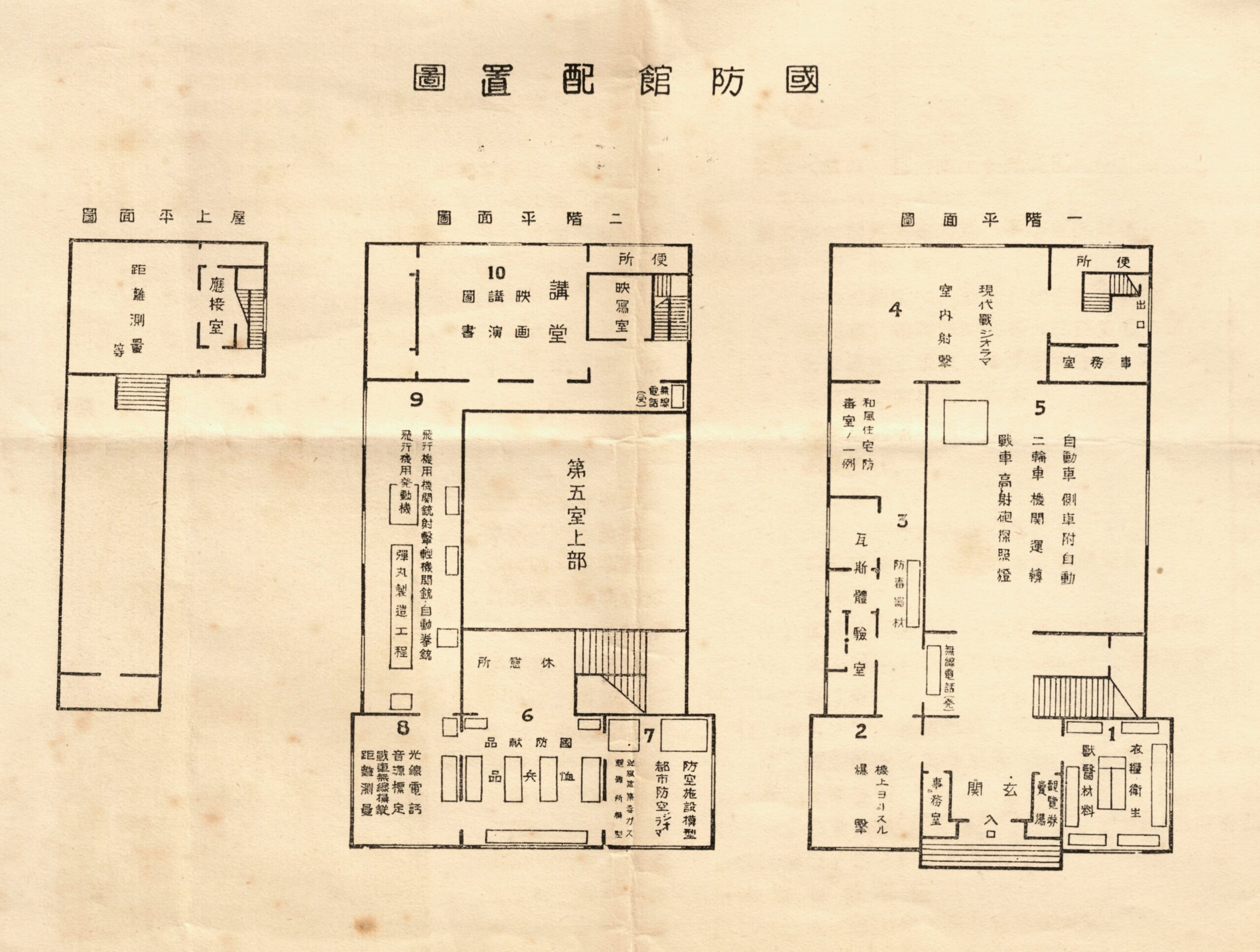

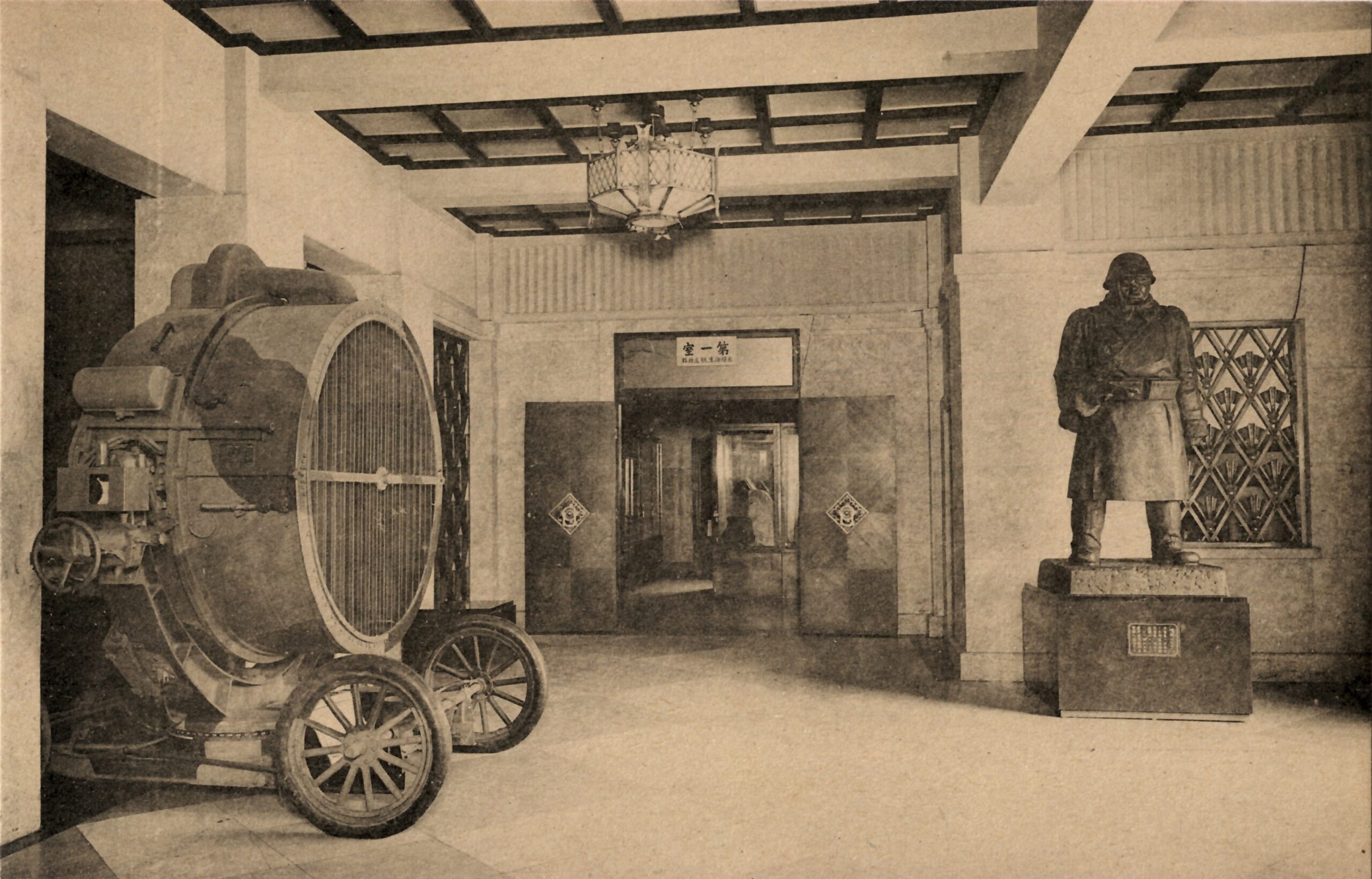

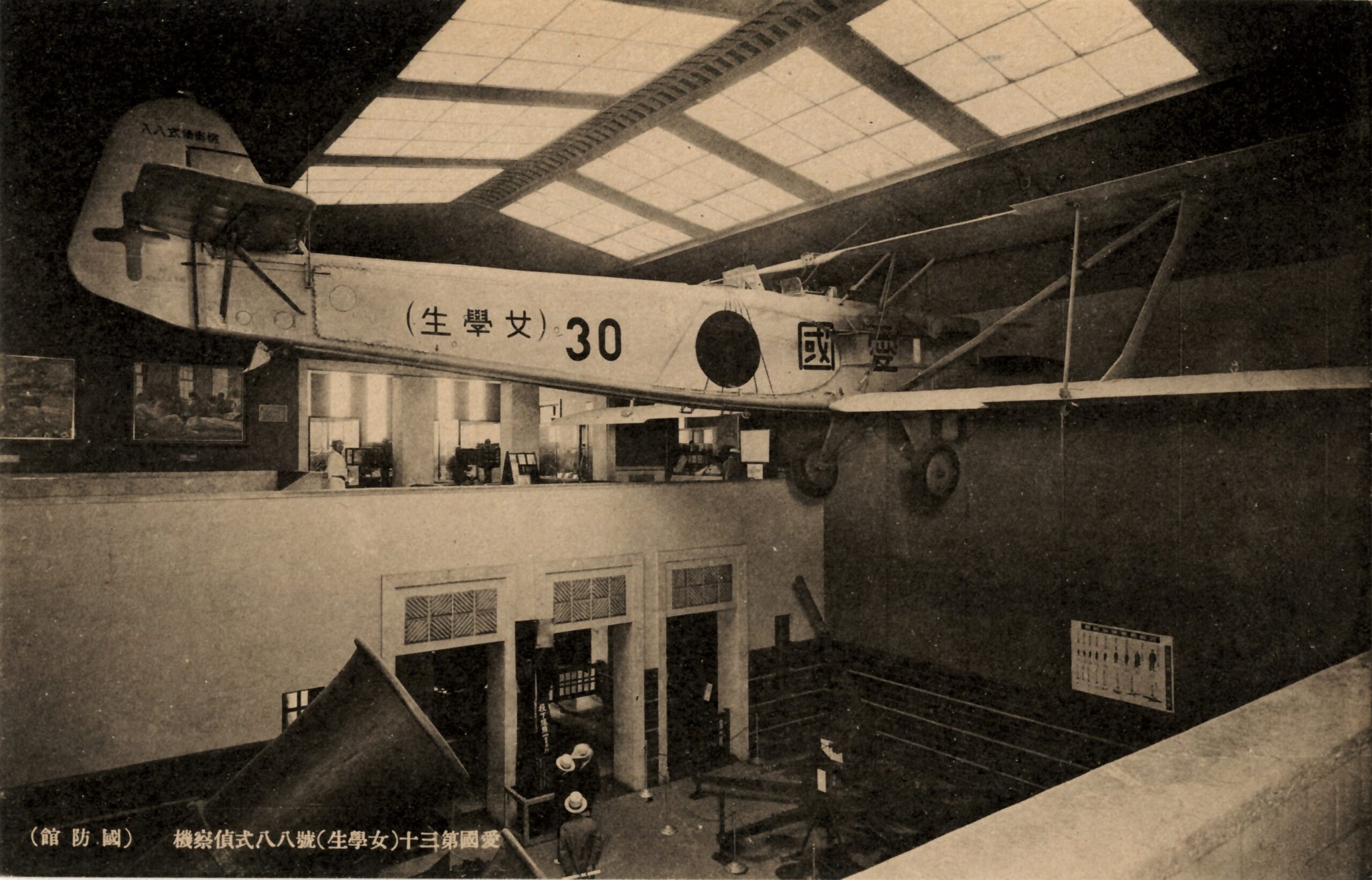

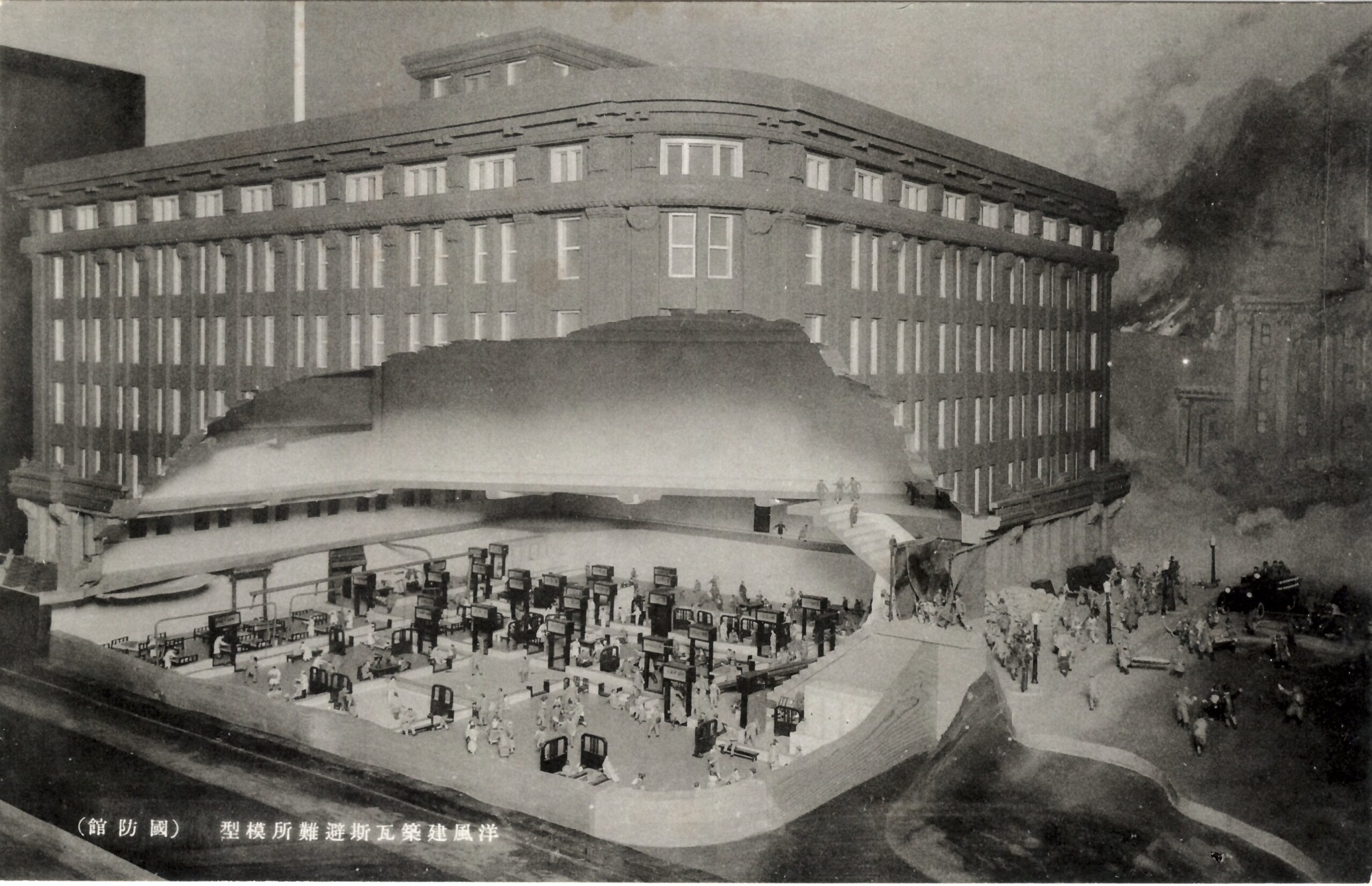

The expansion of Japan’s conflict on the continent, combined with the great popular interest, led to the establishment of a new National Defense Hall (Kokubōkan) directly next to the Yūshūkan. The Kokubōkan was completed in 1934, built with a private donation from Mitani Teiko (dates unknown), widow of the local businessman Mitani Chōzaburō (1869–1934), reflecting civilian engagement with the war effort.97 Although officially modeled on an early modern weapon storehouse, visitors described the design of the Kokubōkan as “reminiscent of an ancient castle,” and commented that it blended well with the architecture of the new Yūshūkan.98

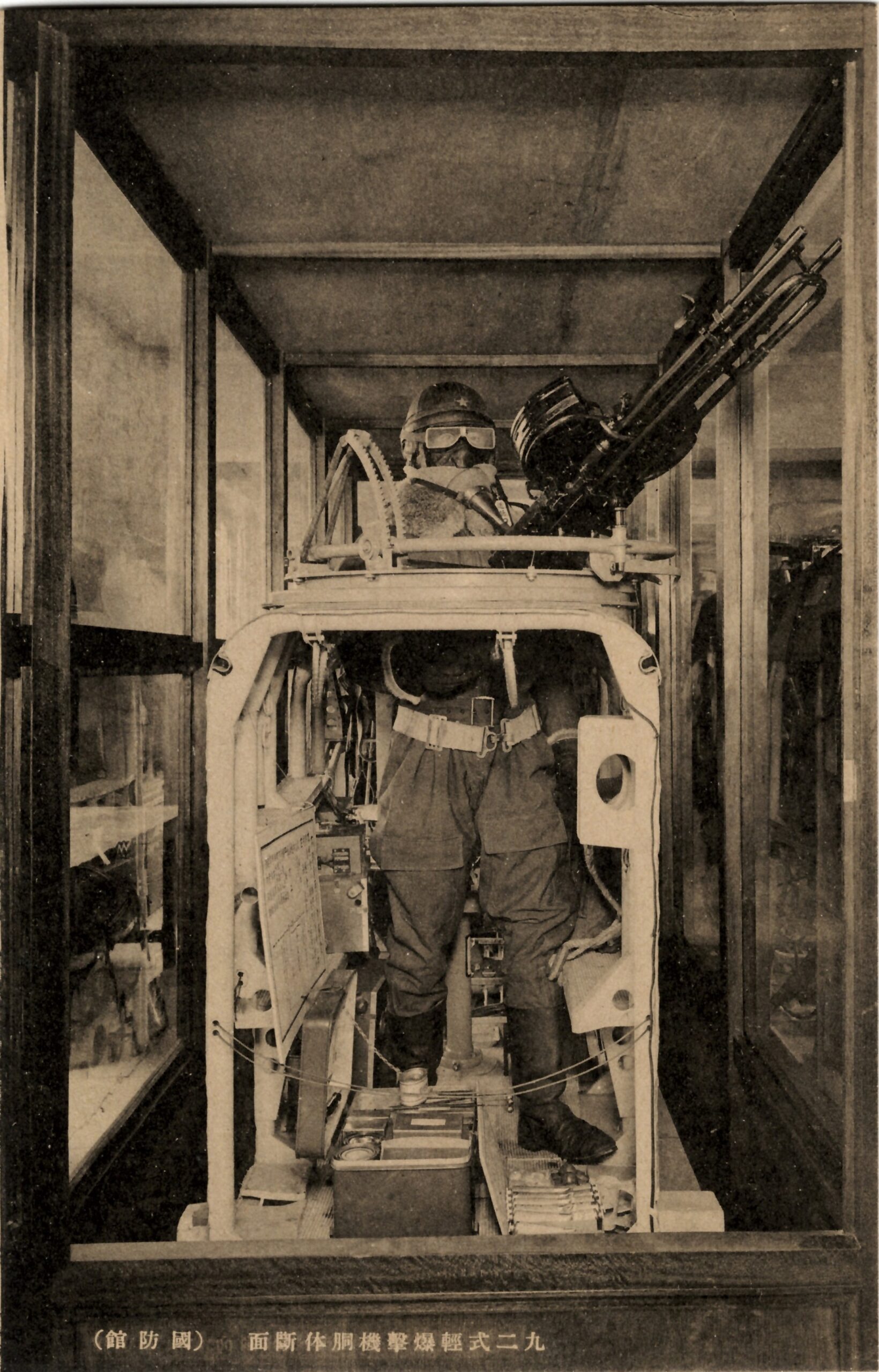

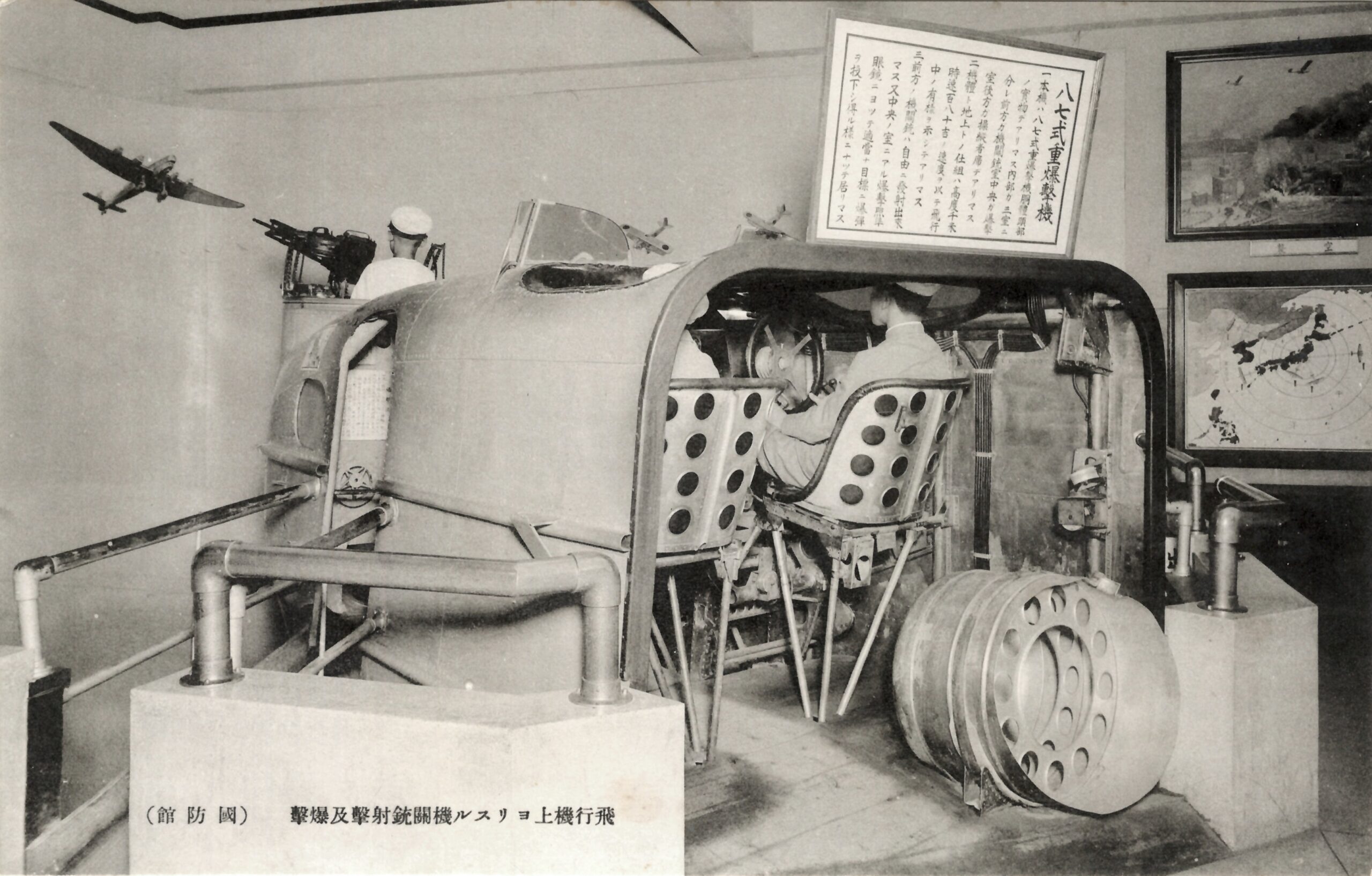

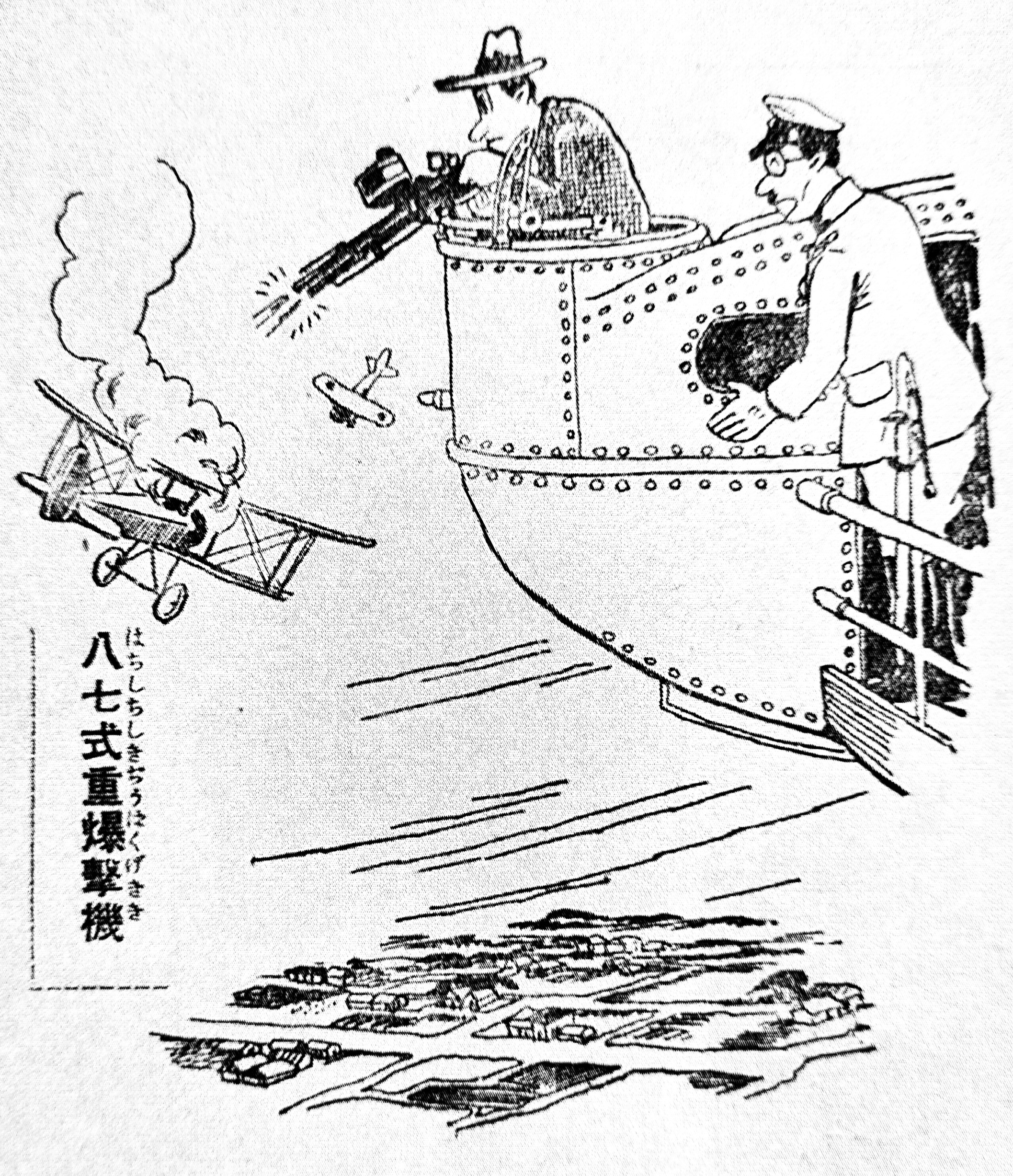

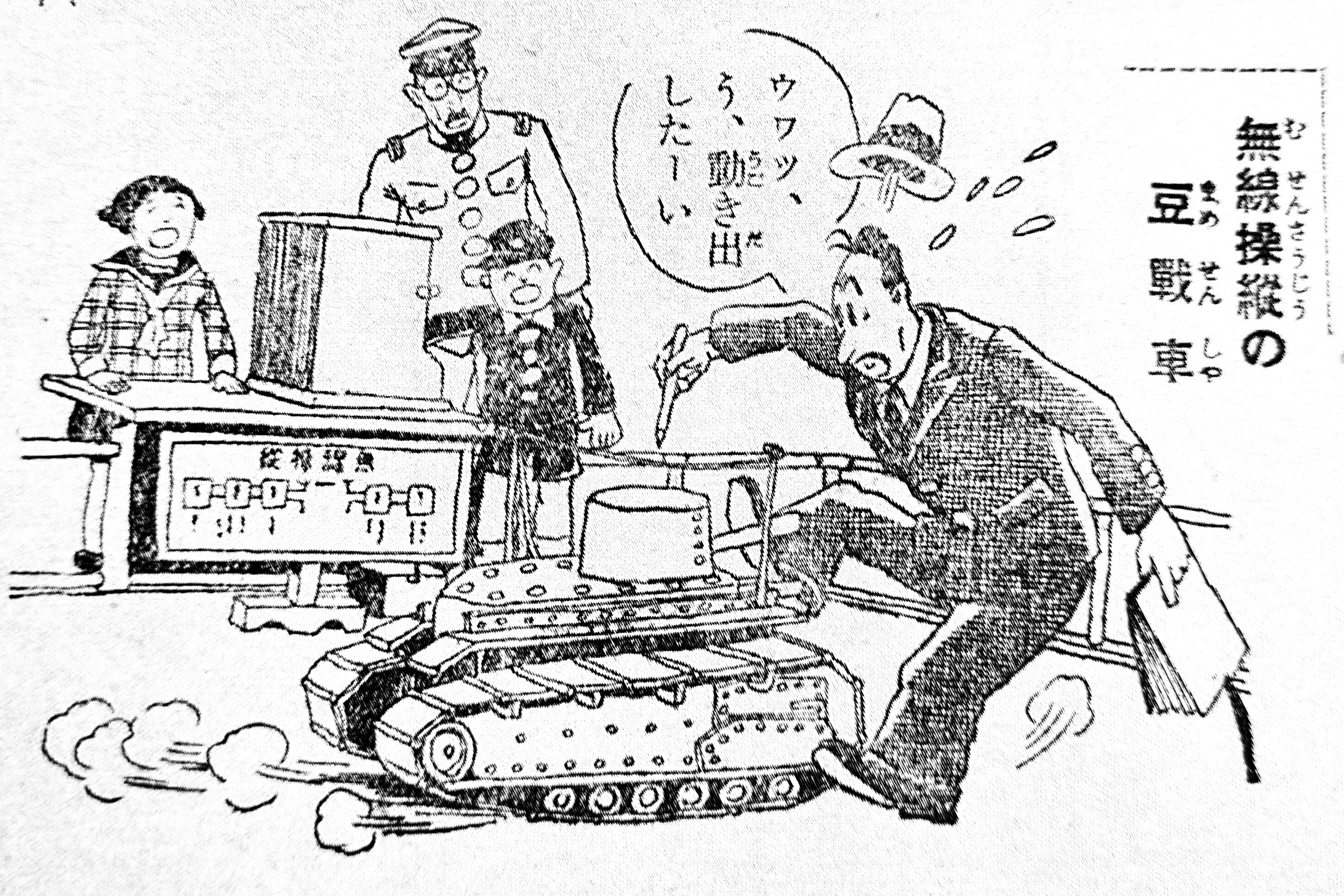

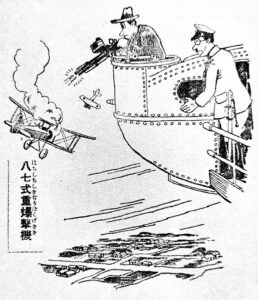

While the Yūshūkan retained its historical focus, the mission of the Kokubōkan was to “disseminat[e] the idea of national defence ideas among the people.”99 To this end, the Kokubōkan showcased the most modern military technology and provided immersive experiences of warfare to its many visitors.100 Exhibits included the front section of a Kawasaki Ka 87 bomber, from which visitors could “shoot down” enemy aircraft projected onto a screen in front of them.101 Another popular exhibit simulated a poison gas attack, whereby visitors wearing gas masks would be placed in a room with tear gas in order to give them a sense of danger.

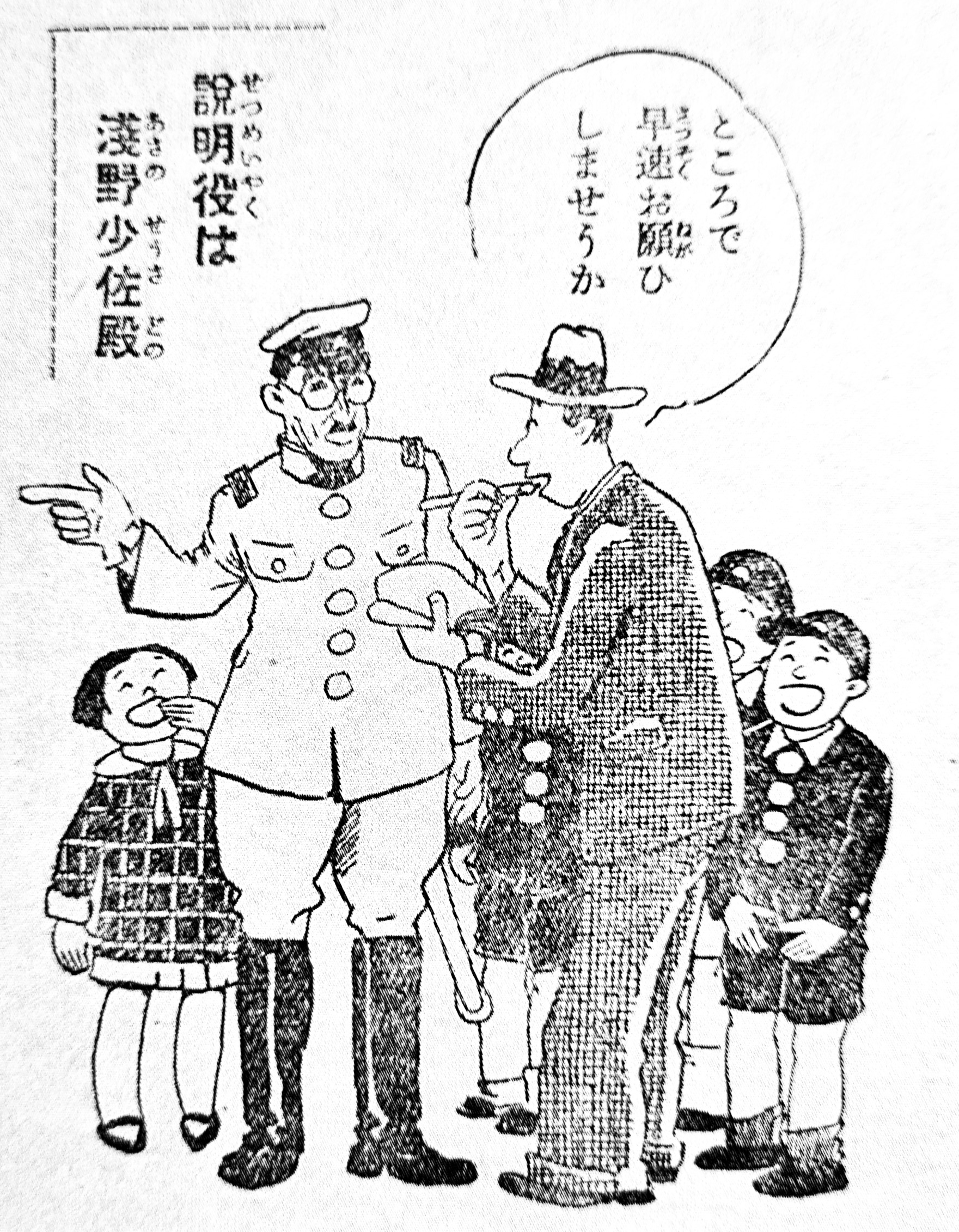

Children were an important audience for the Kokubōkan, as they had been for the Yūshūkan since its early days, and many textbooks and youth magazines published descriptions of these facilities.102 One notable article was published in the magazine Shōnen kurabu (Youth Club) in 1936, and is an account of a visit to the Kokubōkan by the manga artist Shimada Keizō (1900–1973). Shimada accompanies a group of schoolchildren as they are led through the exhibits by Major Asano Kazuo, depicted in full military uniform. Illustrations show Shimada shooting an enemy biplane from the Ka 87 and trying his hand in the shooting gallery, where the target has a human profile. Shimada is also taken into the “poison gas room” by Asano, where he is very anxious about the gas mask. Upon leaving the room and removing the mask, he accidentally gets a tear gas droplet from the outside of the mask into his eye, making him weep uncontrollably as the children laugh at his expense.103

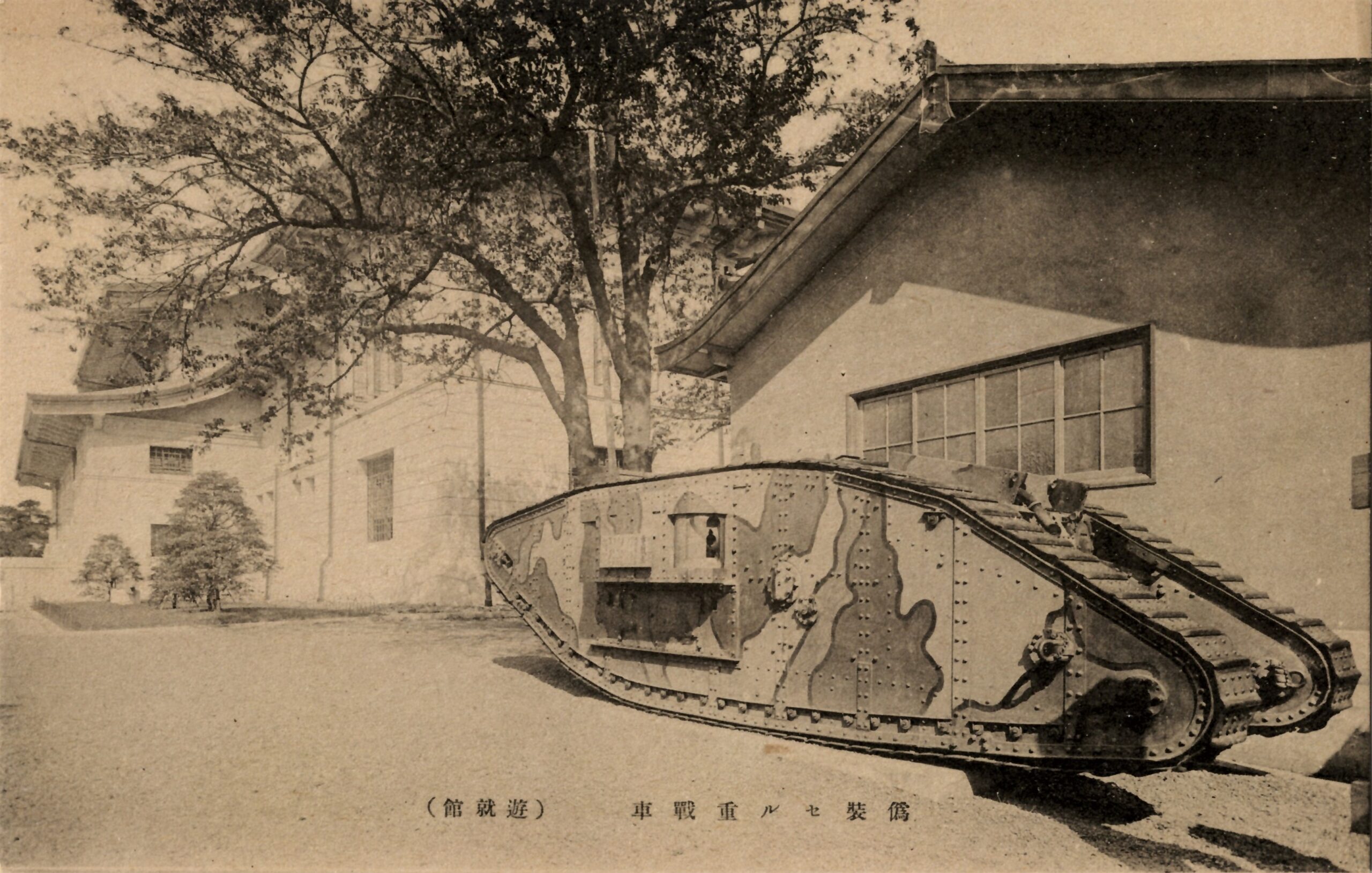

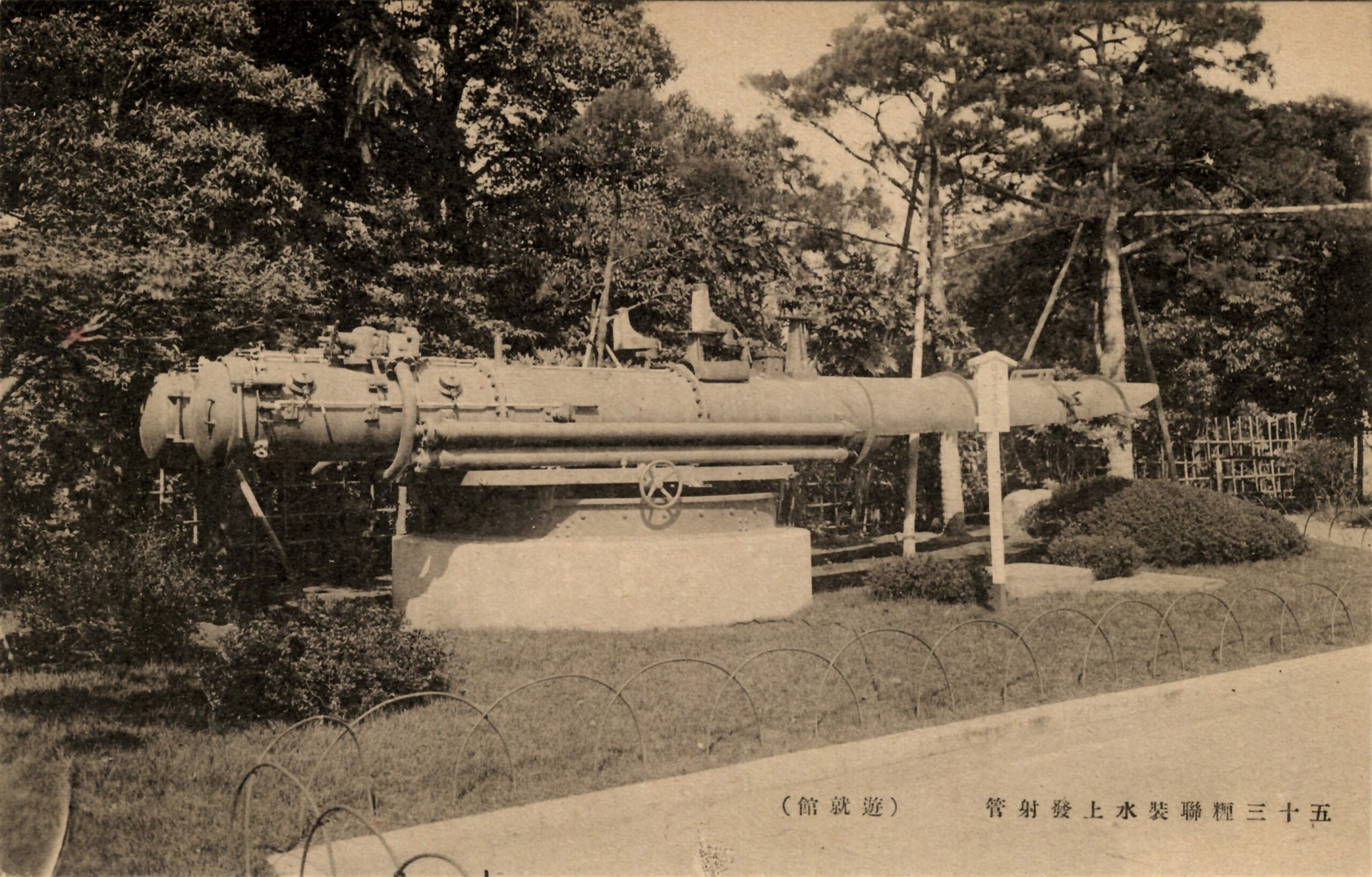

Through the establishment of the Kokubōkan as a site focused purely on contemporary warfare, the Yūshūkan was able to retain its role as a historical military museum, a division of labor that was clearly outlined in official materials and echoed by visitors’ accounts. The official 1934 record of the Kokubōkan explicitly commented on these roles, as well as the fact that the Yūshūkan displayed the historical development of weapons while also encouraging martial virtues. This text stressed the syncretism between the museum and shrine, invoking the “nation-protecting spirit.”104 That being said, the tone suggests that this connection needed to be emphasized rather than being self-evident to the public, reflecting lingering ambiguity and even concern about the relationship between the two institutions. The various buildings on the site were also tied together by the wide range of objects displayed on the grounds, including captured Russian guns, a British tank that was used as a basis for Japan’s own tank designs, as well as Japanese acoustic locators (also known as “war tubas”) and torpedo tubes.

Paul Barclay argues for continuities in the celebration of the military across the five decades before 1945, and the Yūshūkan was especially important during times of war.105 As an article in the youth magazine Shōnen sekai exhorted its readers, “Now Japan is a martial country, a country of war. At this time, surely it would be of great benefit to call upon all youths to visit the Yūshūkan!”106 Just as Yasukuni Shrine’s influence grew over this period, and especially with the establishment of the empire-wide system of gokoku (“nation-protecting”) shrines in 1939 under the leadership of Yasukuni, the Yūshūkan expanded its influence through touring exhibitions and object loans. 1940 saw the opening of the satellite Ōsaka Kokubōkan, also known as the “Western Yūshūkan,” which was built in Osaka Castle with a major private donation from the businessman Nakano Tazaemon in 1935.107 By 1944, many of the exhibits were permanently moved from the Osaka Kokubōkan to the seventh floor of Takashimaya as the castle grounds were closed to the public for wartime security reasons.108 That same year, the main Kokubōkan at Yasukuni devoted its entire exhibition space to air defense.

The situation whereby the Yūshūkan was the most-visited site in Tokyo after the Imperial Zoo was not unique to Japan, however, and was comparable to that in Germany in the late 1920s, where statistics showed that the Zeughaus (arsenal) attracted more than twice as many visitors as the next most popular museum. As a 1928 article in the Japan Times described it, “The Zeughaus boasts the world’s most complete collection of arms and military array, from the early Middle Ages to the World War. There are lifesize medieval knights clad in steelmail, checking their prancing chargers with iron hands.” Furthermore, the walls “are adorned with gigantic mural paintings, depicting scenes from Prussia’s glorious past … pictures whose artistic value has often been disputed,” echoing critical sentiments towards the paintings in the Yūshūkan. The issue of war trophies was more acute in Berlin than in Japan, given Germany’s status as a defeated power, and “The numerous French colors captured by the Germans in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, and once the pride of the entire show, have been returned to France in accordance with a stipulation of the Versailles Peace Treaty.”109 In many ways, the Yūshūkan continued to reflect certain international standards for military museums, and its popularity had parallels elsewhere. Without a doubt, the visiting delegation of Hitler Youth who visited the Yūshūkan in 1938 would have recognized many aspects of the exhibition’s approach.110

War as History and History as Battleground: The Yūshūkan in Postwar Japan

The Yūshūkan sustained limited damage in the bombings of Tokyo in May 1945, and the building itself remained largely intact, although most of the paintings were in a separate storehouse that was completely destroyed by fire.111 Almost immediately after Japan’s surrender, in September 1945, the edict establishing the Yūshūkan was abolished and its links with the military were severed.112 As the shrine’s own published history described this juncture, “the Yūshūkan’s operation as the national military museum stopped after 64 years.”113 Instead, control of the museum was transferred from the Army to the Yasukuni Shrine, which was also privatized and only narrowly escaped complete closure by the U.S. Occupation authorities.114 Until the end of 1945 there was an expectation that both the museum and Kokubōkan would be converted to memorial halls for the fallen, and renamed the “Houses of Bereaved Families” (Izoku no Ie).115 These would not be merely somber sites of veneration and commemoration, but also include amusements such as ping-pong, roller skating, carousels, and a cinema.116 This was not to be. On 25 January 1946, U.S. Occupation soldiers attached to the 7th Cavalry Regiment arrived to clear the museum. They set about the massive historic cannons with electric saws, cutting these up into small pieces and loading them onto Jeeps. All of the objects were taken to the garrison, where the cannon fragments were sold to scrap metal dealers to be melted down, while American soldiers took many of the swords home with them as mementos. In October 1946, the Occupation authorities began to return some of the most valuable items to the Japanese government, including ancient helmets, swords, and firearms. Although these items were only a fraction of the original collection, there was no dedicated storage space, and they were stacked in a small room at the shrine. Many objects were returned to people who had originally donated them to the shrine, and only a handful of pieces remained.117 This account is based on a 1954 article describing the fate of the objects, which was published after the end of the U.S. Occupation and its censorship regime.

A June 1946 report by the shrine corroborates the loss of most of the collection that dated from the period after the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95. Important paintings relating to the Battle of Nanjing and the Battle of Nomonhan were given to the Americans until such a time that Japan “became completely peaceful.”118 Several of the most precious weapons and armors from the Yūshūkan made their way to the Tokyo National Museum, such as the famous iris-leaf helmet said to have been gifted by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, which was in the Yūshūkan collection before 1945.119 Other examples include an oil painting of Nogi Maresuke entering Port Arthur that was donated to the Yūshūkan in 1935 before disappearing after the war and resurfacing and being returned to the shrine in 1981.120 Not only was the Yūshūkan abolished, however, but it lost its physical display space for the long term in 1947, when the museum building became the headquarters of the Fukoku Seimei insurance company, whose former offices had been requisitioned by the Occupation. In the 1950s, the rent paid by Fukoku Seimei was 400,000 Yen per month, an important financial support for the privatized shrine.121 The use of the museum by the insurance company reflects continuing entanglements between commercial and militarist spaces across the transwar years, even if the causality was different.

A first step in rehabilitating the museum occurred in 1959, when the Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi Department Store celebrated its 90th anniversary with a “Yasukuni Shrine Exhibit” that included many objects from the Yūshūkan collection. Building on the success of this event, two years later the shrine reopened the second floor of the former Kokubōkan—now the Yasukuni Hall (Yasukuni Kaikan)—as the “Yasukuni Reliquary and Treasure Hall” (Yasukuni Hōmotsu Ihin Kan), focused on objects from those who had died in the war, including writings from the Himeyuri girls student corps mobilized as nurses for the Battle of Okinawa in 1945.122 The opening of the new exhibition hall was attended by members of the imperial family, who also attended commemorative events at Yasukuni Shrine in the postwar decades.123 Several aspects of this development reflect transwar continuities, including the involvement of the imperial family—who had previously donated objects and visited the Yūshūkan—as well as the private department store and insurance company, but these did not cause significant controversy at the time. In contrast, the highlighting of Okinawan objects should be seen in the context of the movement to revert control of the islands from the United States, a goal that was finally achieved in 1971.

As in the case of the Okinawan objects, the gradual increase in activity around the Yūshūkan reflects the larger political context of the 1960s. Recent work has highlighted the student movements of the 1960s, many of which were pushing for radical progressive change.124 These high-profile activists were also struggling against a conservative revival in Japanese society, which included many imperial symbols such as the Kigensetsu holiday on 11 February that marked the founding of Japan by the mythical emperor Jimmu in 660 BCE. Having been discarded under the US Occupation in 1948, the national holiday was effectively restored following a grueling political campaign by conservative politicians in 1966, albeit under the name “National Foundation Day” (Kenkoku kinen no hi).125 The 1964 Tokyo Olympics proved especially useful for the rebranding and revival of imperial symbols, including the rising sun flag, the figure of the emperor, and the military in the form of the Japan Self Defense Forces.126 Japan’s rapid economic growth during this period bolstered conservative elements and contributed to the limited legacy of the student movements, while also promoting nostalgia for the imperial period before Japan’s defeat.127

Throughout the period of the 1960s and 1970s, the shrine continued to collect materials and documents from veterans, as well as receiving returning objects that had originally belonged to the Yūshūkan. The reopening of the museum was a key aim of Matsudaira Nagayoshi (1915–2005), who became head priest of Yasukuni in 1978 after ten years directing the Fukui City History Museum.128 Through this museum experience, as well as his close connections with his mentor, the ultranationalist and wartime propagandist Hiraizumi Kiyoshi (1895–1984), Matsudaira saw an opportunity to restore Yasukuni Shrine’s status as an educational site, with the Yūshūkan a key aspect of this undertaking.129 Whereas previous displays had focused on the Second World War, in 1978 Matsudaira oversaw the first major exhibition of samurai objects from the Yūshūkan, including historic and replica armor and a small number of swords. This exhibition was held in the former Kokubōkan, and in his foreword to the exhibition catalogue, Matsudaira looked forward to the near future when Fukoku Seimei would move out of the Yūshūkan building, which happened in 1980.130 One of Matsudaira’s first actions as head priest was to obtain a permanent loan of a Kaiten suicide torpedo from the U.S. Army Museum of Hawai’i, and three years later he established a group at the shrine to lead the museum project.131 Indeed, historian Yamada Akira argues that the Yūshūkan has an unusual assortment of objects on display due also to the fact that there were very few weapons left in Japan after the war.132

The revamped Yūshūkan finally opened in July 1986, and counted 250,000 visitors by the end of the following year. The first three special exhibits focused on themes that celebrated both the Yūshūkan and Japan’s older martial heritage: Meiji woodblock prints of Yasukuni Shrine, Yada Isshō’s oil paintings of the Mongol Invasions, and samurai helmets.133 These topics were relatively uncontroversial in contrast to the historical narrative presented in the permanent exhibition, with its focus firmly on a nationalistic apologist view of Japan’s military actions in the imperial period. This fed into the larger controversies that continued to surround the shrine following Matsudaira’s enshrinement of Class A war criminals in 1978, and famously neither the Shōwa Emperor nor his successors have visited Yasukuni after that point. Diplomatic issues arose annually during visits by Japanese prime ministers, which were seen as problematic within and outside of Japan from the 1980s onward.134 The first official visits by a prime minister were by Nakasone Yasuhiro (1918–2019) every August between 1983–1985. These visits were strongly criticized abroad in spite of government attempts to frame the visits as civic acts rather than religious ones, an approach which in turn angered shrine officials by not fully observing the prescribed rituals.135 After Nakasone, the next prime ministerial visit was in 1996 by Hashimoto Ryūtarō (1937–2006), but the greatest controversy occurred during the premiership of Koizumi Jun’ichirō, who visited the shrine five times during his time in office from 2001–06, and began the practice of visiting on 15 August, the anniversary of the Japanese surrender. These visits drew powerful reactions from other Asian nations, as well as the United States, and were the subject of several lawsuits from Koizumi’s opponents within Japan.136

The great level of controversy was in no small part related to the presence of the Yūshūkan, with its clear—and controversial—historical narrative that came to be known as the “Yasukuni view of history.” In a 2006 interview with TBS television, U.S. Ambassador to Japan Tom Schieffer rejected the repeated arguments that Koizumi was visiting the shrine, not the Yūshūkan, stating that he disagreed with the view of history in the museum. Direct criticism of the Yūshūkan’s revisionist historical narrative in this context also came from the former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, as well as Chinese and Indonesian diplomats and politicians.137 The high-profile debates surrounding Koizumi’s visits to Yasukuni were also closely tied to the major refurbishment and expansion of the Yūshūkan that was undertaken in 2002 at a cost of 4.9 billion yen, greatly raising the profile of the facility.138 This can be seen as a continuation of Matsudaira Nagayoshi’s own intentions when re-opening the Yūshūkan in the 1980s, and he had envisioned it as an income source for the larger shrine. Yuzawa Tadashi (1929–1989), head priest from 1997–2004 during the renovations of the Yūshūkan, hoped that the new exhibits would speak to young people and foreign visitors. Certainly, the modernized exhibition spaces contributed to an increase in visitor numbers to a peak of more than 360,000 in 2005, rivalling prewar figures.139 With the exception of Abe Shinzō (1954–2022) in December 2013, post-Koizumi prime ministers have not visited Yasukuni. International backlash following Abe’s visit kept him from visiting Yasukuni again, although his wife, Abe Akie, visited both the shrine and Yūshūkan on his behalf on several occasions.140

Seventeen years ago, John Breen could still write that “In all of its literature, the Yūshūkan defines itself as Japan’s oldest and most esteemed war museum; its remit being to ‘clarify the truth about Japan’s modern history.’”141 For visitors to the Yūshūkan in the third decade of the twenty-first century, this narrative has become less pronounced. Breen identified a tendency among certain staff to refer to it not as a museum, but rather as “a hōmotsuden or repository of the relics of the war dead; its sole purpose is to honour the memory of Japanese war dead.”142 Indeed, official materials no longer use the terms “military museum” or “war museum,” and they have disappeared from the Yūshūkan website. Matthew Allen and Rumi Sakamoto have considered the museum in the context of its message of peace, describing it in 2013 as “something of an anachronism, and in many ways … an oxymoron. Formally embracing peace, the museum celebrates the sacrifices made by Japanese soldiers during war.”143

Even if the Yūshūkan now puts forward a more uniform narrative regarding its official status as primarily a site of veneration and commemoration, it cannot control how it is seen by others. To most domestic and overseas visitors, the Yūshūkan is a military museum they recognize from other contexts, just as prewar Japanese travelers recognized military museums as the “Yūshūkans” of Berlin, London, Vienna, or Munich. However, the Yūshūkan also presents a narrative that goes against dominant interpretations of the Second World War found in other countries. The sense of anachronism observed by Allen and Sakamoto a decade ago is more pronounced today, as military museums in many other countries have changed significantly in response to cultural and social shifts. As Hacker and Vining argue, military museums are inherently conservative, and only in the 1980s did most of these institutions in Europe and North America begin to draw on the new military history that engaged substantively with the role of the military in society and the experience of ordinary soldiers.144 In the sense of its treatment of the war experience of Japanese soldiers, the Yūshūkan may once again have been ahead of its time, even if its larger historical narrative can be seen as quite the opposite. The description of the Yūshūkan found in a very popular English-language guidebook in 2008 captures some of the tensions: “[the Yūshūkan] starts, fittingly enough for a war memorial, with stately cases depicting Japan’s military heritage and traditions, punctuated by swords and samurai armour, and art and poetry extolling the brave, daring, and indomitable spirit of the Japanese people.” The book observes the revisionist history—such as the downplaying of the Nanjing Massacre—presented throughout the galleries, as well as the moving final exhibits focused on individual war dead. It concludes, “as such, the feeling engendered by having to pay to visit a place of such solemnity can be mixed—feelings the attached gift shop, selling gaily decorated biscuits, chocolates and curry, doesn’t do much to dispel.”145

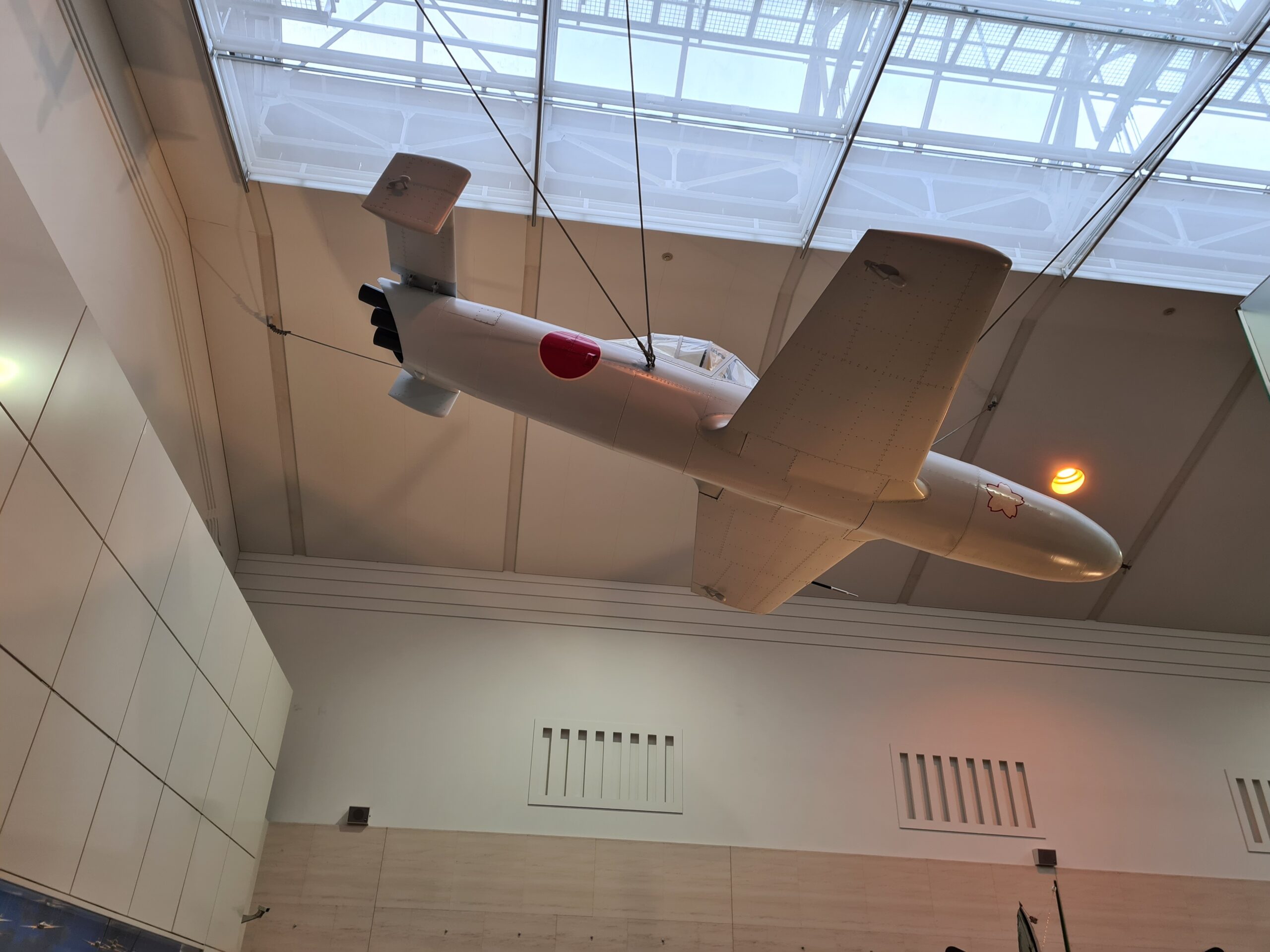

Breen also highlighted another seemingly unique aspect of the Yūshūkan relative to military museums in other countries, which is the conspicuous “absence of the enemy” in the narratives presented at the site.146 This is especially true of the absence of the United States and its allies in the Second World War. It is not only the narratives, however, but also in the objects themselves that the enemy is absent. From the Zero fighter in the entry hall to the Kaiten torpedo and Ōka suicide aircraft, from samurai swords and armor to soldiers’ personal effects, the objects on display are almost exclusively Japanese. This is a significant departure from the Yūshūkan in the imperial period, when Gatling guns, oil paintings, and other foreign objects were prominently displayed, to be subsequently joined by trophies from Japan’s modern wars. The enemy was very much present, unless objects were removed to avoid offending visiting dignitaries. Beyond the objects themselves, the interpretive language of the Yūshūkan today approaches the “history in the passive voice” seen at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Shōwakan, and other institutions related to the wartime period.147 The Second World War, especially, appears almost as an unavoidable natural disaster, with the objects on display bearing witness to this national tragedy.

Conclusions

In its origins, and for most of its history, the Yūshūkan was unabashedly a military museum under the control of the Imperial Japanese Army. Immediately before it was closed in the process of demilitarization under the U.S. Occupation, it came under the control of the Yasukuni Shrine and was rebranded a reliquary in an attempt to preserve the institution in some form, although this move could not prevent its ultimate closure. From this point onward, although the Yūshūkan did not exist in name or in practice, temporary exhibitions and the reopening of the former Kokubōkan as the Yasukuni Kaikan emphasized the aspects of veneration and worship of the fallen. The role of the Yūshūkan as a military museum was not forgotten, however, and was from the outset integral to Matsudaira’s plans to reopen the facility. From the realization of this goal in 1986, the Yūshūkan has sought to claim both of these identities: reliquary and military museum—specifically a war museum dedicated to the Second World War. Indeed, even as early as 1989, there were attempts to portray the Yūshūkan as a uniquely Japanese “shrine museum” as opposed to the “military museums” or “weapons museums” of other countries.148

Although objects have come and gone, the current Yūshūkan contains the symbolic elements that it accumulated over its long and often controversial history. It draws on a specific selection of these for different audiences, but these elements will not always be seen in the way that they are intended. The Yūshūkan portrays itself as a place of veneration and commemoration, but the narratives of veneration and commemoration also face challenges in attempting to draw younger generations when the number of veterans and their immediate family members are rapidly declining. At the same time, promotional materials and the arrangement of displays such as the dramatically-placed fighter aircraft in the entryway, as well as the items in the gift shop, draw visitors in the manner of a traditional military museum. The Yūshūkan also reflects the difficulties of being a military museum of a defeated nation with a martial past that remains controversial and unresolved, and more specifically being a war museum dedicated primarily to a conflict that resulted in great loss of life and national trauma, as well as foreign occupation.

Over the past 140 years, the Yūshūkan has played many roles. It has been a pathbreaking institution not just in Japan but in a global context as one of the first modern military museums. More recently, it has been viewed as a controversial anachronism inseparable from the Yasukuni Shrine. Over this long period, the Yūshūkan has gone from appealing to an emerging global standard to claiming a Japanese uniqueness as justification for its existence, and, as this study has shown, it has always been closely intertwined with global discourses on war, commemoration, and Japan’s place in the world.