Abstract: Despite being a party to the Refugee Convention since 1981, Japan has historically admitted very few asylum seekers. However, recently the country’s total protection rate has increased, from 2.3% in 2020 to 52% in 2022. This article explores this seemingly dramatic shift in Japan’s refugee policy, tying the increased rate of asylum admissions to the country’s broader foreign policy in the face of recent geopolitical challenges in Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine, while outlining the diverging pathways of admission utilized in each case.

Keywords: Japanese Refugee Policy, Japanese Foreign Policy, Negative Cases

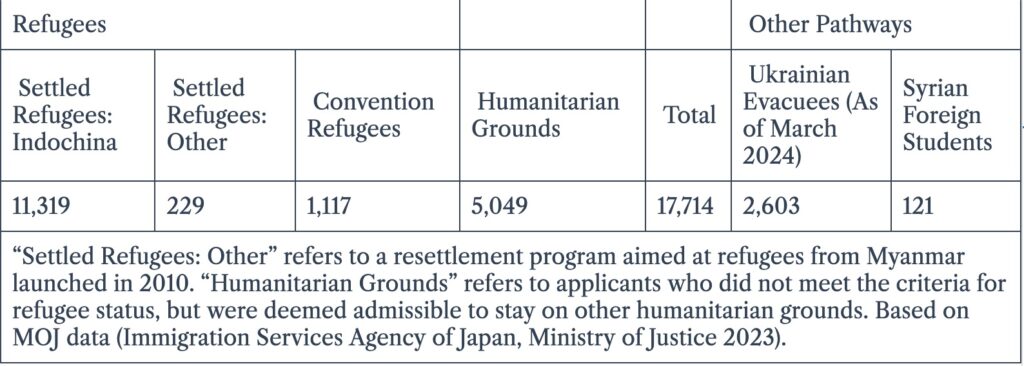

Japan’s modern refugee policy began in earnest following the fall of Saigon in 1975, which marked the end of the Vietnam War and resulted in the Indochina refugee crisis. During the later stages of the war and its aftermath, Japan had to balance its relationship with the U.S. and its strategic interest for stability in the region, gradually moving towards engagement with North Vietnam and a push for peace (Pressello 2023). While the country began to invest massively in the region, both through reparations for its role in World War 2 and Official Development Assistance (ODA), Japan initially did not take on a pro-active role in dealing with the refugee crisis (Havens 1990). As the number of refugees fleeing the region increased towards its peak in the years 1978–80, so did both domestic and international pressure on the Japanese government. Eventually, the country reversed course from being a transit country for Indochinese refugees to hosting them. Successive cabinet decisions, starting with the one on April 28, 1978, gradually expanded the admission quota and support for their resettlement (Ministry of Justice 2012). In all, Japan would admit 11,319 Indochinese refugees (see Table 1)—a small number given the scope of the crisis, but significant for the country’s refugee policy trajectory. Indeed, this experience would directly lead to Japan acceding to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees in 1981, and then to the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees in 1982.

Japan as a “Negative Case” of Refugee Admission

Since then, Japan’s refugee policy has arguably built on the historical antecedent of its immediate post-Vietnam War approach of primarily extending financial assistance—a form of “checkbook diplomacy.” The country has contributed significant financial aid towards the protection and resettlement of refugees, most notably by being one of the largest individual donor countries to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR): Japan gave more than US$167 million in 2022. At the same time, it has admitted an extremely small number of asylum seekers to the country. In the four-plus decades since ratifying the Convention and Protocol, Japan has only admitted a total of 6,395 asylum seekers—although, this figure does not count the 2,603 Ukrainian evacuees it has admitted since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the 121 Syrian foreign students admitted under a special program launched in 2016, which was developed in coordination with the UNHCR with the goal of creating educational opportunities for young Syrians fleeing the civil war. Still, this is a lower total number than what many of Japan’s close allies in North America and Europe admit in a single year. For example, Germany granted humanitarian protection to 137,101 applicants in 2023, while the United Kingdom did so for 62,336 asylum seekers (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees 2024; Home Office 2024).

One reason for Japan’s low admittance of refugees is its geographical location as an island nation in East Asia, far removed from the major modern refugee-producing areas in the Middle East and Africa. However, geography alone cannot explain Japan’s reluctance to extend refuge to those needing protection—the country could, for instance, follow the Canadian model of resettling a set number of refugees that have been granted protection elsewhere.

Table 1: Total Number of Asylum Seekers Admitted to Japan, 1978–2022

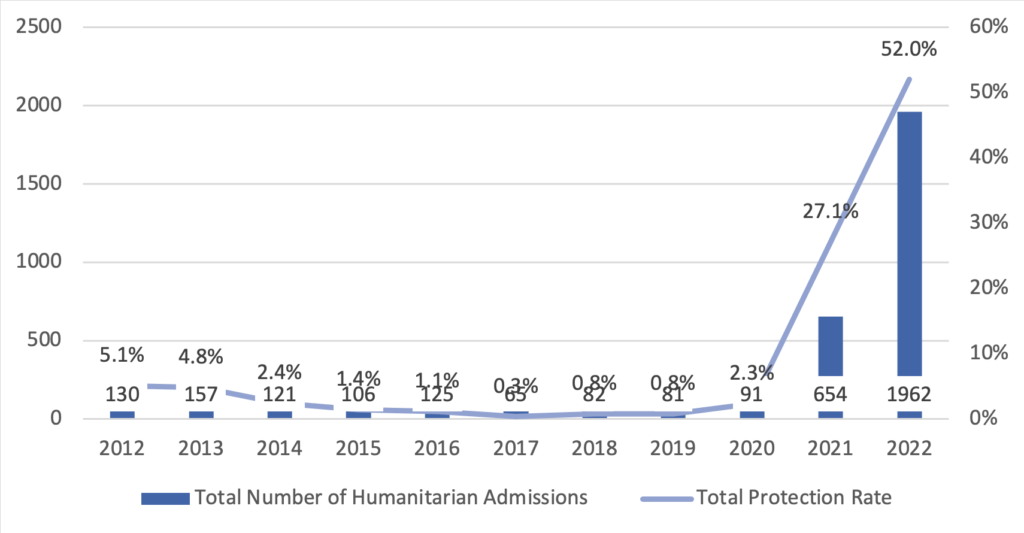

There is another reason for the low amount of asylum seekers granted protection in Japan: the country’s miniscule rate of recognizing asylum. In the year with the largest number of asylum seekers on record, 2017, Japan granted protection to 65 applicants out of a total of 19,629, for a total protection rate (TPR) of 0.33% (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2023b). The TPR combines the rate of refugee recognitions with the rate of asylum seekers admitted on general humanitarian grounds and is the UNHCR’s preferred measure to gauge the rate at which countries offer protection. More recently, in 2020, Japan’s rate stood at 2.3%. Overall, both the historically low absolute numbers of asylum seekers granted protection, and the rate at which protection is granted, stand in clear contrast to Japan’s generous financial contributions to the UNHCR.

It follows then that it is Japan’s particular aversion to accepting asylum seekers that has led to broad-ranging scholarship attempting to explain why this is the case. These include studies that focus on a broader transnational perspective. While Japan’s admission of Indochinese refugees has been attributed, at least in part, to international pressure (Havens 1990; Strausz 2012), this pressure has since not existed as a coercion mechanism (Wolman 2015). Other scholars focus on domestic dynamics, including Japan’s national identity as a homogenous country (Tarumoto 2019), domestic politics more generally (Kalicki 2019), and more technical institutional factors. For instance, scholars have pointed out the strict application of refugee law and high burden of proof as evidence of bureaucratic “rigidity” in the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), the primary governmental organ responsible for the administration of refugee policy (Akashi 2006). Even very recently published articles cited Japan’s low refugee recognition rate as one reason why Japan is failing to live up to its commitments to the rules-based international system it rhetorically champions (Hein 2023). In migration studies, scholars often talk about “positive” and “negative” cases of migrant labor admission, with the historic example of post-war Japan until the 1980s famously being cited as a negative case (Bartram 2000). Both Japan’s record on refugee protection and previous scholarship makes it clear that the country has been, for almost the entirety of its post-war history, a negative case of refugee admission.

Recent Trends: Granting Asylum at Historic Rates

In the last two years, however, both the total number of asylum seekers that have been granted protection as well as Japan’s TPR have increased significantly (see Figure 1). The TPR increased to 27.1% in 2021 and reached 52% in 2022. In that year, Japan granted protection to 1,962 out of 3,772 asylum seekers. Again, these figures do not include the more than 2,500 Ukrainians Japan has admitted since February 2022. Considering these developments, this article reconsiders Japan as a negative case of refugee admission and outlines how and why Japan’s refugee policy has seemingly undergone this rapid shift. While considering recent changes on the institutional level and other domestic factors, I will focus primarily on the changing origin countries of those asylum seekers admitted and their geopolitical context.

Figure 1: Japan’s Total Number of Humanitarian Admissions and TPR, 2012–2022

There are three countries that have accounted for the majority of recent humanitarian admissions to Japan: Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine. However, policymakers have utilized a very different approach for each, sometimes relying on already established legal pathways, sometimes adopting a new legal framework, and sometimes implementing a combination of both. The second major aspect of this analysis will thus be to outline the background as to why Japan has adopted these diverging pathways, which relate closely to the specific circumstances surrounding each country.

Therefore, I will develop my analysis by discussing the Japanese approach to humanitarian admissions from these countries as three separate case studies. To go into more detail, these are: (1) the liberal granting of right of stay on humanitarian grounds for citizens of Myanmar following the January 2021 coup d’état; (2) the blanket recognition of charter refugee status for a subset of Afghani citizens following the Taliban takeover in August 2021; (3) the admission of Ukrainian evacuees following Russia’s invasion in 2022. Beyond refugee policy, these three events—in combination with a broader geopolitical shift in the region—have led to Japan adapting its foreign policy. I argue that Japan’s recent shift to grant more asylum seekers protection can be understood as part of these foreign policy changes, which includes more pro-active regional and international engagement, as well as a recommitment to international and transnational institutions framed within values-based language. In my conclusion, I question whether Japan’s recent policy shift is sustainable, considering both the geopolitical factors that made it possible as well as recent concrete policy changes. This paper is sourced mainly on primary government documents—including from the political executive (e.g., the Cabinet Secretariat), the MOJ, and National Diet recordings—and augmented by secondary academic sources to provide additional context as necessary.

The Changing Origin Countries of Asylum Seekers and Grantees

Before looking at the three case studies in detail, it is important to compare the origin countries of both applicants and those admitted for asylum in 2017 and 2022 to establish change over time. 2017 was the year with both the highest number of asylum seekers and lowest TPR on record. 2022 is the latest year for which data is available at time of writing and thus the most relevant for an up-to-date comparison. As outlined above, both the total number of asylum seekers granted protection (65 in 2017, 1962 in 2022) and the TPR (0.33% 2017, 52% in 2022) have increased significantly in what is a relatively short time. Table 2 shows the top five origin countries for both asylum seekers and those granted protection for the two years in question.

Table 2: Top Five Origin Countries, Asylum Seekers and Grantees, 2017/2022

While the reduction in overall applicants can probably be explained due to the lingering effects of border control measures following the COVID-19 pandemic, a quick glance at Table 2 shows two other significant trends. First, there is a discrepancy in the origin countries of applicants and those granted protection—persons being granted asylum in Japan generally do not come from the same countries that account for most applicants. This is especially evident in the data for 2017 and relates to the primary reason that the Japanese government has historically given to explain its low acceptance rate: that most applicants do not come from major refugee producing countries and are rather economic migrants seeking a pathway to residence in Japan. Indeed, the MOJ gave the following reasoning for its low TPR in 2017:

“Based on the UNHCR’s press release titled “Global Trends 2016” (released June 2016), applicants from the top 5 refugee producing countries (Syria, Colombia, Afghanistan, Iraq, South Sudan) numbered only 36 in total. Overall, while the number of asylum seekers to our country has increased rapidly in recent years, the majority of applicants do not come from countries that produce many refugees and displaced peoples.” (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2018, 2)

In the same report, the MOJ also pointed out that most applicants were working aged men, bucking the global trend towards asylum seekers including many women and children. In the 2010s, there was a clear trend showing a rise in applicants from traditional labor migrant-sending countries in South and Southeast Asia following the 2010 decision to allow asylum seekers to work in Japan while awaiting the results of their application (Kalicki 2019). While this fact does not absolve Japan from their international commitments under international refugee law completely, it does at least partly explain the low TPR for 2017.

The second notable trend from Table 2 is the fact that two countries (three if including Ukrainian evacuees) account for the overwhelming number of asylum seekers admitted to Japan: Myanmar and Afghanistan. While the discrepancy between the origin countries of applicants and those granted protection remains intact, this underscores the argument made in the introduction to this piece: the cases of Myanmar and Afghanistan are especially noteworthy to understand the increase in Japan’s TPR as they account for an overwhelming majority (97.4% in 2022) of the country’s recent humanitarian admissions. In addition, the fact that the country admitted more Ukrainian evacuees (2,238)—even though they do not count towards the TPR—than the record-number of asylum seekers admitted (1,914) in 2022 further warrants inclusion of the Ukrainian case within the context of this article.

Diverging Pathways of Entry

While zeroing in on the three cases that will be the focal point of this paper, another important thing to note is that while the Japanese government has granted nationals of Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine the right to stay in the country based on humanitarian grounds, the legal pathways it chose have diverged (see Table 3). In the case of Myanmar and Afghanistan, Japan utilized the existing legal framework of its asylum policy, though it primarily granted protection based on humanitarian grounds to citizens of Myanmar, while relying on formal refugee status for citizens of Afghanistan. In the case of Ukraine, authorities decided to denominate Ukrainians to be resettled in Japan as “evacuees,” which legally places them outside of formal asylum policy—although the government very much framed their admittance on humanitarian grounds. I will outline the background behind the government’s decision to utilize these diverging pathways in more detail below, as they arose based on the context of each individual case, but simultaneously carry important implications for Japan’s refugee policy moving forward.

Table 3: Pathways to Admittance for Displaced Peoples from Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine, Total Number Admitted in 2021 and 2022

| Asylum Policy | Other Pathways | |||

| Convention Refugees | Humanitarian Grounds | Evacuees | Designated Activities | |

| Myanmar | 58 | 2,180 | – | 9,527 |

| Afghanistan | 156 | 12 | – | 329 |

| Ukraine | – | – | 2,238 | 2,013 |

Finally, the Japanese government also granted citizens of all three countries who were already in Japan as the situation in their home country deteriorated the right to stay under the Designated Activities residence status. This was done as an “emergency measure” in order to safeguard those who would have had to return home otherwise due to their previous residence status expiring, and also falls outside the framework of formal asylum policy—although persons granted stay this way can still apply for asylum (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2023a). These emergency measures are especially relevant in the case of Myanmar, given the comparatively high number of Burmese citizens that were already living in Japan prior to 2021. Starting with the next section, I will outline each case individually, focusing primarily on the geopolitical and strategic background of Japan’s decision to grant asylum and the way it chose to do so.

Case 1: Myanmar After the 2021 Coup D’état

On February 1st, 2021, the Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military) initiated a coup d’état against the democratically elected civilian government headed by the National League for Democracy (NLD), in turn led by long-time party chief and former State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi. The NDL had won another landslide electoral victory in the 2020 elections, with the new government set to be sworn in on February 2, 2021. Instead, the military instituted a new State Administrative Council that assumed responsibility over all state legislative, judicial, and executive functions. At the same time, supporters of the democratically elected government formed the National Unity Government (NUG) in exile. Following a crackdown against anti-coup protests throughout the first half of 2021, the NUG’s armed wing, the People’s Defense Force (PDF), began a campaign of armed resistance and insurgency against the Tatmadaw. This eventually escalated into a civil war, with the PDF fighting alongside numerous armed ethnic militias against the military junta. This civil war is ongoing at time of writing and has resulted in the humanitarian situation in Myanmar deteriorating significantly, with the UNHCR estimating that 2.35 million people have become internally displaced, in addition to 109,000 new refugees fleeing towards neighboring countries (UNHCR Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific 2024b). Furthermore, the eruption of conflict has had a compounding effect on previously displaced ethnic minorities, most notably the Rohingya.

From the perspective of Japan, the civil war in Myanmar is important due to its prior economic engagements with the country as well as its implications for regional security. Myanmar is located in a strategically important region to Japan, at the crossroads of South and Southeast Asia. Furthermore, it is a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). As such, it is unsurprising that Japan has consistently maintained cordial bilateral relations in addition to multilateral engagement through ASEAN, while being a major investor in the country through ODA. Though the extent of Japan’s diplomatic engagement and financial investment has historically depended on the government in power, and has notably increased in the period of democratic transition beginning in 2011 and until the renewed military takeover in 2021, the country has maintained some level of engagement throughout most of the post-war period (Seekins 2015). In a way, Japan’s relationship mirrors its approach towards the region, historically prioritizing stability and economic development over values-based diplomacy. It is thus unsurprising that Japan had working ties with both the Tatmadaw and the civilian government.

However, the 2021 coup and subsequent escalation into a civil war has forced Japan to take a firmer stance against the Tatmadaw, aligning itself closer with its G7 allies. On February 3, Japan signed the collective statement by G7 foreign ministers condemning the coup. The next day, then Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga spoke on the matter in the National Diet, stating that “we are requesting the restoration of the democratic government in the strongest terms” (National Diet Library 2021). Around the same time, State Minister of Defense Yasuhide Nakayama outlined another aspect related to Japan’s interest in Myanmar: competition with China. In an interview with Reuters, he said that “Myanmar could grow further away from politically free democratic nations and join the league of China”(2021). Like Japan, China also maintained a long-standing interest in Myanmar that resulted in increased economic investment in recent years, including through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, while both countries had arguably been competing for influence in the country, this competition was not exclusionary, meaning that from Myanmar’s perspective, it was not a zero-sum proposition, but rather complementary (Hong 2014). For instance, Japan’s engagement was more focused on developing business ties (especially in manufacturing) and civil society, while China prioritized the development of natural resource extraction and building supply chains for its energy needs (including through the BRI). Through this dynamic, the two countries could thus co-exist as important partners for Myanmar.

This status quo has changed since 2021 because China and Japan have taken opposing sides in the conflict, thus being more directly in competition. Since the coup, Japan has suspended new loans and scaled back some of its existing ODA projects in the country—although Japan’s refusal to end all ongoing projects has been a point of criticism from pro-democracy activists (Justice for Myanmar 2023). On the other hand, China has emerged as arguably one of the key backers of the military junta, continuing its economic investments, providing military aid, and vetoing United Nations Security Council resolutions on the matter. While Japan’s historic focus on stability and development have led it to develop strong ties with autocratic regimes in the region, the 2021 coup has resulted in Japan taking a more values-based approach, oftentimes framing its condemnation for the military’s actions as upholding democracy, as well as being on the side of the regional and international community. This approach was most likely taken with an eye towards isolating China’s stance on the issue. Indeed, the differences in the two country’s approaches were explicitly highlighted in Japan’s 2023 annual defense white paper (Ministry of Defense 2023). Again, as indicated through the statement by Nakayama cited above, this has happened within the context of more direct competition with China—both in Myanmar and beyond.

Considering this background, it then makes sense that Japan was relatively quick to extend the right to stay towards citizens of Myanmar following the 2021 coup. It would be inconsistent to denounce the dismantlement of the previous government, condemn the military’s violent tactics against its own citizens, and call for the restoration of democracy without offering protection for the country’s citizens. This is especially relevant due to the fact that—unlike in the cases of Afghanistan and Ukraine—the Japan-Myanmar relationship extends beyond diplomacy and economics to also include migration. In 2021, more than 37,000 Burmese citizens were residents of Japan (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2022a). Myanmar is among the countries that have seen the number of migrant workers going to Japan increase in recent years, leading to the resident population of Burmese citizens in Japan to more than triple over the ten years prior to the 2021 coup. This means the priority of the Japanese response was to ensure that nobody was sent back to Myanmar amidst the extremely unstable situation developing there due to their residence status expiring.

With that goal in mind, the MOJ instituted the aforementioned “emergency measures” for citizens of Myanmar residing in Japan on May 28, 2021, allowing continued stay in Japan under the Designated Activities residence status for either six months or one year, and allowing for renewal (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2022b). This status also lets the holder to engage in work for up to 28 hours per week. In 2021 and 2022, a total of 9,527 Burmese citizens were granted stay in Japan under these measures, which do not require status holders to apply for asylum (Table 3). On the other hand, there was also a subset who applied for refugee status anyways, undoubtedly for the additional protection the status grants under both domestic Japanese and international law. The vast majority of these applicants in 2021/22 whose cases were decided were not granted formal refugee status (58 in total), but rather protection under humanitarian considerations (2,180).

Overall, the Japanese government can be commended for acting quickly to grant the right of continued stay to Burmese citizens who were already residing in Japan. The decision to enact emergency measures was likely done with an eye towards bureaucratic swiftness, sidestepping the lengthy asylum process to grant immediate resolution. However, this has also invited understandable criticism. In a National Diet session on the matter on October 26, 2022, Katsuhiko Yamada, a politician from the opposition Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDP), pointed out that by denying the greater legal protections and benefits that formal refugee status holds and relying on a short-term work visa (even though it is renewable), Japan is not truly living up to its responsibility for would-be asylum seekers from Myanmar (National Diet Library 2022c). Similarly, even within the realm of asylum policy, Japan also holds greater discretionary power over those it admits on humanitarian grounds in comparison to formal refugee status, including in the type and length of residence status it grants and on issues such as family reunification.

Confronted with a new geopolitical reality in Myanmar following the events of February 2021, Japan has had to rethink all aspects of its foreign policy vis-à-vis the country, including its refugee policy. Considering the significant number of Burmese citizens already residing within its borders, Japan maintained logical consistency in its response by enacting emergency measures to allow for continued stay. However, the decision to largely sidestep the official legal framework of asylum law does pose continued questions about Japan’s ongoing commitment to international refugee law.

Case 2: Afghanistan after the 2021 Taliban Takeover

On August 15, 2021, the Taliban captured the Afghan capital of Kabul, following years of insurgency and a months-long offensive against the U.S.-backed Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (IRA) government in place from 2004. The pace of the Taliban offensive in 2021 escalated following successive U.S. troop withdrawals, with IRA security forces offering only limited resistance. Overall, the fall of the IRA signified the failure to establish a sustainable long-term government following the dispossession of the previous Taliban government in 2001, ending the 20-year attempt at peacebuilding in the country by the U.S. and its allies. While the 2021 Taliban offensive and subsequent takeover was largely a low-intensity conflict and did not result in a complete deterioration of the security environment, the implications of a Taliban-led administration for Afghan citizens employed by the previous government and its backers, as well as for women and other ethnic and sexual minorities, led to a renewed refugee crisis. The UNHCR estimates that 3.25 million Afghanis are internally displaced, while a further 1.6 million have fled the country since August 2021 (UNHCR Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific 2024a).

While Afghanistan does not carry with it the regional significance that Myanmar does for Japan, the country did assume an enhanced importance in Japan’s foreign engagements after 2001 for two main reasons (Barno 2024). First, Afghanistan became a country of great diplomatic significance for Japan’s most important ally, the U.S., both as a security threat following the 9/11 terrorist attacks and as a peacebuilding project after the initial invasion. The Japan-U.S. security alliance has arguably been the single most vital bilateral institution shaping Japan’s post-war foreign policy. It follows then that Japan would play a part in Afghanistan in support of the U.S.

Second, Afghanistan became a significant project for Japan in the context of its evolving foreign policy on a more general level. Starting in the 1990s and following its limited function in the Gulf War—where the country provided billions in financial assistance, but was criticized for not playing a more direct role—Japanese policymakers decided to shift towards a more activist foreign policy that included a security component (Ashizawa 2014). While Japan’s pacifist constitution constrains the use of its Self-Defense Force (JSDF) in offensive military operations, successive revisions to the legal framework governing the JSDF have allowed the government to deploy them more pro-actively (Gustafsson, Hagström, and Hanssen 2018). In Afghanistan, the JSDF deployed several ships to the Indian Ocean to provide refueling and other technical and logistical support as part of U.S-led counter-insurgency operations from 2001 to 2010. Furthermore, the country was one of five to play a leading role in security-sector reforms. Japan also hosted two major conferences, in 2002 and 2012, aimed at coordinating the reconstruction effort, in which it played a major part as well. From 2001 to 2021, the country provided about US$7 billion towards reconstruction, with direct involvement in implementing infrastructure, education, and healthcare programs through the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

It is this prolonged, pro-active, and direct involvement in Afghanistan that is also at the root of Japan’s refugee policy following the 2021 Taliban takeover. To coordinate Japan’s multi-pronged engagement in the country, it employed a significant number of local staff at its embassy and JICA office in Kabul. It thus became the priority of Japanese authorities to evacuate these staff members and their families, which numbered about 500 in total. Initially, the Japanese government asked the JSDF to send 4 airplanes in August 2021 to airlift them to safety. However, after this operation failed due to logistical and operational issues, Japan engaged the Taliban directly through their temporarily relocated embassy in Doha and negotiated their evacuation in the latter half of 2021 (Barno 2024). Furthermore, Japan allowed the return of Afghan former foreign students who were admitted to Japanese universities through a JICA program, meaning that the total number of Afghan citizens who have arrived in Japan since August 2021 numbers more than 800 (Asakura 2023). Finally, the MOJ also instituted emergency measures for Afghan citizens already in Japan, essentially copying the measures it took in response to the coup d’état in Myanmar (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2023a).

In the case of Afghanistan, the Japanese government has primarily utilized formal refugee status for the local staff it employed and their families. It extended refugee status primarily to former Japanese embassy staff in 2022, while doing the same for former JICA staff members in 2023 (NHK News 2023). While the latter cohort, which numbers at least 114, has not been reflected in the data I rely on in this article—as official government figures for 2023 are not available at time of writing—a total of 158 Afghan citizens were granted refugee status in 2021 and 2022 (Table 3). In addition, 12 Afghan citizens were granted protection under humanitarian considerations, while 329 were granted the residence status Designated Activities under the emergency measures.

The key difference between the case of Myanmar and Afghanistan is the use of formal refugee status primarily targeting former local staff employed by the Japanese government and related organizations. In addition to protection under international law, formal refugee status entitles the holder access to the full Japanese social safety net, long-term stay with a path to permanent residence, family reunification, and access to Japanese language education and cultural/lifestyle orientation classes. As then Minister of Justice Yasuhiro Hanashi pointed out in the National Diet in his comments on October 26, 2022, the key difference between the cases is that for Myanmar, the government primarily targeted Burmese citizens already in the country, a majority of whom would not have been eligible for formal refugee status under the MOJ’s interpretation of international refugee law (National Diet Library 2022c). In Afghanistan, however, local staff were obviously residing in the country as the situation changed in August 2021. Overall, the extension of protection for local staff in areas of conflict is standard practice—other allies such as the U.S. and Germany undertook similar measures in the case of Afghanistan—and thus a logical consequence of Japan’s more activist foreign policy in the country.

Case 3: Ukraine after the 2022 Russian Invasion

On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. This came after about eight years of low-intensity conflict and hybrid warfare in the eastern parts of Ukraine following the Maidan Revolution and Russia’s unilateral annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014. While the Ukrainian armed forces repelled an initial assault on Kyiv in the early days of the war and regained territories in Kharkiv and Kherson in the second half of 2022, the frontlines have largely stabilized since then—although high rates of casualties at the line of contact have been reported throughout. In addition, recent fighting has been punctuated by Russia’s continued aerial attacks on Ukrainian civilian and military infrastructure, as well as drone-based counterattacks on Russian naval and military assets. Overall, the war is the deadliest on the European continent since World War 2 and has resulted in a large-scale humanitarian crisis. At time of writing, the UNHCR estimated that 3.69 million Ukrainians are internally displaced, and have recorded a total of 6.48 million global Ukrainian refugees (UNHCR Regional Bureau for Europe 2024).

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Japan had friendly diplomatic relations with Ukraine following its independence, stepping up support in coordination with the G7 following the events of 2014 (Shigeki 2022). However, Ukraine had not assumed the same level of significance for Japan’s foreign policy as Myanmar or Afghanistan, and the country’s sanctions on Russia following 2014 were largely symbolic. This changed dramatically following February 24. The next day, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida condemned the invasion in the strongest terms, calling it an act that “shakes the foundations of our international order” and a “blatant violation of international law” (National Diet Library 2022a). Since then, Japan has become the most significant supporters of Ukraine in monetary terms, both bilaterally and through the G7, outside of Europe and North America (Kiel Institute for the World Economy 2024).

The country enacted significant sanctions on Russia, including prohibiting semiconductors and other high-technology exports, freezing Russian assets, pausing the issuance of visas, as well as enacting individual sanctions on high-ranking members of the Russian regime. Japan has also provided about US$7.53 billion in overall support to Ukraine and has already committed to several billions more (Kiel Institute for the World Economy 2024). This has primarily included non-military aid, including humanitarian, healthcare, technology, and infrastructure support, but a recent loosening on export restrictions of lethal military aid—previously banned in relation to the country’s pacifist constitution—could open the door for the provision of finished military equipment (Tajima 2023). While the new rules still bar Japan from supplying parties to an active conflict, such as Ukraine, it is now possible to export lethal military equipment to countries such as the U.S. and European allies to replenish their stockpiles, allowing them to then transfer more of their stock to Ukraine. Finally, Japan pledged its long-term commitment towards the reconstruction of Ukraine as part of a major conference hosted in Tokyo on the matter in February 2024 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2024). It has reopened its JICA office in Kyiv to coordinate these efforts, with a Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) office soon to follow.

Especially when considering the cases of both Myanmar and Afghanistan as contextual background, Japan’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine has accelerated its trajectory towards a more activist foreign policy, including a heavier focus placed on security, while underscoring the country’s commitment to its alliance with the U.S., multilateral partners within the G7, and the “West” more generally. Furthermore, as seen in its response to the coup in Myanmar, Japan has increasingly adopted more values-based language. In the Ukrainian case, Japan has doubled down on language related to territorial integrity, international law, and unilateral changes of the status quo—all principles it espouses through its commitment to a “free and open international order underpinned by the rule of law” (Ministry of Defense 2023, 29). In addition, the government has vowed to “never forgive Russia’s actions” (Ministry of Defense 2023, 35) while describing the “killing (of) a large number of innocent civilians” as war crimes (Cabinet Public Affairs Office 2023, 1).

Of course, Japan’s strong condemnation of Russia and support for Ukraine, in addition to it consistently highlighting values such as territorial integrity and international law, can also be viewed within the context of the geopolitical challenge posed by China in its own backyard, specifically in the South China Sea. From Japan’s perspective, it is China that is threatening the status quo, including in territorial disputes related to the “nine-dash line,” the Senkaku Islands, and Taiwan. Therefore, the Ukraine policy adopted by Japan is partly driven by its own aim to deter China (Brown 2023).

In terms of refugee policy, Japan’s response was an extension of the country’s firm stance on Ukraine. In what is arguably a first for the country, Japan has tied the admittance of Ukrainians following Russia’s invasion directly to its larger response—thus incorporating asylum policy into its foreign policy toolkit (Cabinet Public Affairs Office 2023). Starting in April 2022, Japan launched a program for what it calls Ukrainian “evacuees.” Unlike in the cases of Myanmar and Afghanistan, this program functioned closer to a classic refugee resettlement program. Japan provided weekly flights from Poland, a comprehensive support infrastructure upon arrival that included counselling, language classes, and job matching, as well as a daily stipend to cover the transitional period (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2024). The Japanese government allocated close to US$20 million for the program in 2022 and 2023, which was implemented by the MOJ in coordination with multi-tiered governmental and non-governmental actors. A total of 2,603 Ukrainians were admitted to Japan under the program, of which 2,099 remain in Japan at time of writing. In addition, the government also extended emergency measures for Ukrainian citizens already residing in Japan similarly to the cases of Myanmar and Afghanistan. A further 2,013 Ukrainians remained in Japan under these measures in 2022 (Table 3).

The Japanese program for Ukrainian evacuees was swiftly implemented, granting extensive support at all phases of the resettlement process. However, like the Japanese response in the Myanmar case, there is one obvious point of criticism: the decision to sidestep the existing legal framework for asylum. The Ukrainians granted humanitarian protection by Japan were “evacuees”—a neologism created specifically for this case—and not refugees. Again, this has led to a debate between the ruling party and opposition politicians in the National Diet. For instance, Japanese Communist Party (JCP) politician Taku Yamazoe argued that according to UNHCR guidelines, those fleeing from war should be granted formal refugee status and questioned the government’s commitment to the Refugee Convention (National Diet Library 2022b).

Here too, the Japanese government has argued that this was done to prioritize speed, and unlike in the case of Myanmar, the support offered to Ukrainian evacuees is very close to the support it offers those granted formal refugee status. Still, Japan’s decision to grant Ukrainians fleeing the war humanitarian admittance as evacuees does call back to its approach for Indochinese refugees—with one important caveat: unlike in the late 1970s, Japan is now party to international refugee law. Thus, Japan has once more foregone the application of the international legal process vis-à-vis refugees under the laws to which it is a party by denying formal refugee status, choosing instead to maintain full legal discretion over the process.

Japan’s Refugee Policy Trajectory Moving Forward

The recent geopolitical events surrounding Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine have prompted significant shifts in Japan’s foreign policy approach, although these arguably occurred as part of a larger trajectory towards becoming a more pro-active diplomatic actor with more direct involvement and a stronger security component—as indicated by its Afghanistan policy until August 2021. Following the 2021 coup in Myanmar and the subsequent escalation into civil war, Japan took a firmer stance against the military junta, aligning itself more closely with its G7 allies and scaling back its previous strategy of economic engagement. Conversely, the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine propelled Japan into a leading role in supporting Ukraine, both bilaterally and through multilateral avenues like the G7. This evolving foreign policy approach has been punctuated by more values-based language, specifically as it relates to the rules-based international order, and an even greater focus on security, reflecting Japan’s broader strategic interests and its aim to counter regional challenges, notably that of China. As Singh (2024) outlines, Japan has become the “front-line guardian of the status quo.”

These trends have been reflected beyond the three case studies presented here as well. Since the second Abe administration, Japan has incorporated the free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) framework as a core pillar of its regional foreign policy, which has also been adopted by the U.S. Under current Prime Minister Kishida, Japan has furthermore announced significant investments in security, pledging to almost double its defense budget which would signify defense spending equivalent to 2% of GDP. The country has also continued to act more pro-actively through regional initiatives such as the quadrilateral partnership between Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S. (Quad) and the new trilateral cooperation between Japan, South Korea and the U.S, in addition to penning numerous security-based investment deals with regional partners under its new Official Security Assistance (OSA) framework.

As I have outlined, Japan’s increased willingness to extend humanitarian protection to asylum seekers is a logical consequence of Japan’s evolving role on the global stage and its efforts to navigate complex geopolitical dynamics. Japan has doubled down on the international system, from which the country has broadly benefitted throughout its post-war history and of which international refugee law is an undeniable part. Does this shift then signify a lasting, sustainable change—is the country no longer a negative case with regards to refugee policy?

Looking beyond the headline figures such as TPR and delving into the specifics of how Japan has chosen to apply asylum policy reveals numerous caveats, many of which relate to the diverging pathways Japan has chosen to utilize in the cases I have analyzed. First, even when incorporating every single pathway that I have discussed as part of Japan’s multi-pronged response to the crises in Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine, the country has only admitted (in this context including those already in Japan that were granted status to remain) a total of 16,513 displaced peoples (Table 4). While this is a significant improvement by Japan’s own low standards, the country still has very low humanitarian admissions in comparison with many of its closest allies. For example, when comparing the total refugee population across G7 nations, Japan ranks dead last at 17,406 as of 2022. The next closest country is Canada which hosts over 140,000 refugees, while Germany tops the list with a refugee population of over 2 million (World Bank, n.d.).

Second, the country has opted to apply a selective policy that has resulted in a majority of admissions coming through pathways outside of the legal framework of asylum policy. While it is true, as the Japanese government has argued, that Japan’s responses were tailor-made to the specific circumstances of each individual case I have outlined, this point of criticism still holds. Eighty-six percent of total admissions occurred through alternative pathways that do not guarantee the same protections in either domestic or international law as those offered through asylum policy. Third, even within the framework of asylum policy, Japan has only granted formal refugee status to a small share of applicants and has only consistently done so in the special case of former local staff working for the Japanese government and related organizations in Afghanistan. Overall, it is clear that even when offering pathways to residence based on humanitarian considerations, Japan maintains a significant amount of discretionary legal power over the process.

Table 4: Japan’s Response to Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine, 2021–2022

| Asylum Policy | Other Pathways | ||||

| Convention Refugees | Humanitarian Grounds | Evacuees | Designated Activities | Total | |

| Myanmar | 58 | 2,180 | – | 9,527 | 11,765 |

| Afghanistan | 156 | 12 | – | 329 | 497 |

| Ukraine | – | – | 2,238 | 2,013 | 4,251 |

| Total | 214 | 2,192 | 2,238 | 11,869 | 16,513 |

| % of Total | 1% | 13% | 14% | 72% | 100% |

Finally, the sustainability of Japan’s refugee policy remains an open question. As I have argued, the country has chosen to be more pro-active in extending humanitarian protection due to specific foreign policy considerations in the three cases outlined. However, it is unclear whether this will translate to a renewed commitment to more pro-actively extend such protection beyond these cases. With this in mind, I want to take a brief look at some recent institutional changes that Japan has undertaken that point to how the country’s refugee policy trajectory could develop.

First and most significant is the launch of a new pillar of Japan’s refugee policy in December of 2023 called Complimentary Protection (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2023c). This framework applies to people who fall outside of the formal definition of being a refugee, i.e., a person that is unable to return to their home country based on reasons related to race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion. Essentially the new system institutionalizes an additional pathway for protection beyond the more loosely defined “humanitarian grounds” and is built upon the precedent of the support granted to Ukrainian evacuees. It includes comprehensive provisions similar to those granted to formal refugees, including offering language classes, cultural orientation, job matching support, and a pathway to permanent residence. Many countries have adopted a similar framework for additional protection, and Japan’s decision to formalize allows for more flexibility when admitting displaced persons based on humanitarian grounds. This new system also indicates that Japan will no longer need to develop ad-hoc programs in the manner it has done for Ukrainian evacuees. Furthermore, the MOJ published revised guidelines that serve to clarify and update their rigid interpretation of international refugee law. Developed in consultation with the UNHCR, these guidelines are significant because of new provisions that explicitly added fear of prosecution based on sexuality or gender as applicable reasons to seek asylum (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2023d). These updates to Japan’s institutional framework do suggest that recent events could be sustainable, and that Japan will continue to adopt a more pro-active asylum policy.

On the other hand, the country passed an amendment to the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (ICRA) in the spring of 2023 that essentially makes the deportation of asylum seekers who have been rejected multiple times easier. This law came within a context of an increase in asylum seekers incarcerated at Japan’s immigration detention facilities, of which a significant number are repeat applicants. While the law also places a limit on how long people can be detained, it was the implications of the loosened measures for deportation of asylum seekers for the principle of non-refoulement that have drawn strong criticism from human rights and migrant support organizations (Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan 2023). The bill had originally been tabled for early 2021 but was withdrawn after widespread protests following the death of a Sri Lankan asylum seeker, Wishma Sandamali, in a Japanese immigration detention facility. Indeed, the conditions at Japan’s immigration detention facilities, which have led to 17 deaths of detainees since 2007, also need to be addressed.

In conclusion, given Japan’s very limited history of granting humanitarian protection, the recent efforts to provide swift support to displaced peoples from Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine are commendable. At the same time, Japan has granted such protection through case-by-case responses that were tailor-made to the specific circumstances of each country, oftentimes bypassing the formal asylum process. This does not serve to quell questions about Japan’s commitment to international refugee law. The recently unveiled Complimentary Protection framework can also be seen in this light. While it does institutionalize the support granted to Ukrainian evacuees and thus makes it easier to offer similar measures in the future, how it is eventually applied will determine whether the new system is an additional pathway to extend humanitarian protection, or a more formalized tool to retain legal discretion over the asylum process. Similarly, the application of the recent amendment to the ICRA, in addition to how Japan will further reform its immigration detention facilities, will be a focal point in measuring the country’s commitment to humanitarian protection moving forward. As Japan continues to navigate global crises and geopolitical challenges by doubling down on values-based language that increasingly and explicitly underscores the principles of international law, the country must back its words with more action to truly become a positive case for people seeking refuge within its borders.

Acknowledgements: This work was supported by JST, the establishment of university fellowships towards the creation of science technology innovation, Grant Number JPMJFS2145. The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Akashi, Junichi. 2006. “Challenging Japan’s Refugee Policies.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 15(2): 219–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/011719680601500203.

Asakura Takuya. 2023. “元大使館職員のアフガン難民、日本で困窮 ウクライナと支援に差 (Afghan Refugees That Were Former Japanese Embassy Staff Report Economic Hardship in Japan).” Asahi Shimbun, October 6. https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASRB6721SR9TPTIL00S.html?iref=ogimage_rek.

Ashizawa, Kuniko. 2014. “Japanese Assistance in Afghanistan: Helping the United States, Acting Globally, and Making a Friend.” Asia Policy 17(1): 59–65.

Barno, Suyunova. 2024. “Japan’s Participation in the Reconstruction of Afghanistan.” American Journal of Public Diplomacy and International Studies 2(3): 115–22.

Bartram, David. 2000. “Japan and Labor Migration: Theoretical and Methodological Implications of Negative Cases.” International Migration Review 34(1): 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791830003400101.

Brown, James D. J. 2023. “The China Factor: Explaining Japan’s Stance on Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 28. https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/89156.

Cabinet Public Affairs Office. 2023. “Japan Stands With Ukraine: Most Recent Measures As of October 19, 2023.” https://japan.kantei.go.jp/ongoingtopics/pdf/jp_stands_with_ukraine_eng.pdf.

Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. 2024. “Aktuelle Zahlen Ausgabe: Dezember 2023 (Current Statistics for December 2023).” https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Statistik/AsylinZahlen/aktuelle-zahlen-dezember-2023.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4.

Gustafsson, Karl, Linus Hagström, and Ulv Hanssen. 2018. “Japan’s Pacifism Is Dead.” Survival 60(6). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00396338.2018.1542803.

Havens, Thomas R.H. 1990. “Japan’s Response to the Indochinese Refugee Crisis.” Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science 18(1): 166–81.

Hein, Pat. 2023. “When Domestic Interests and Norms Undermine the Rules-Based Order: Reassessing Japan’s Attitude toward International Law.” Asian Journal of Comparative Politics 8(4): 895–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/20578911231168206.

Home Office. 2024. “How Many People Do We Grant Protection To?” February 29. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/immigration-system-statistics-year-ending-december-2023/how-many-people-do-we-grant-protection-to.

Hong, Zhao. 2014. “Japan and China: Competing for Good Relations with Myanmar.” The Journal of East Asian Affairs 28(2): 1–23.

Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice. 2018. “平成29年における難民認定者数等について (The Admission of Asylum Seekers in 2017).” https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/930003622.pdf.

———. 2022a. “Zairyū Gaikokujin Tōkei 2021 Nen 12 Gatsu (Foreign Resident Statistics as of December 2021).” https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00250012&tstat=000001018034&cycle=1&year=20210&month=24101212&tclass1=000001060399&tclass2val=0.

———. 2022b. “本国情勢を踏まえた在留ミャンマー人への緊急避難措置(改訂)(Emergency Measures for Citizens of Myanmar Considering the Situation in Their Home Country (Revised)).” https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/001349360.pdf.

———. 2023a. “令和4年における難民認定者数等について (The Admission of Asylum Seekers in 2022).” https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/001393012.pdf.

———. 2023b. “我が国における難民庇護の状況等 (The Admission of Asylum Seekers to Our Country).” https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/001393014.pdf.

———. 2023c. “補完的保護対象者認定制度 (The System of Complimentary Protection).” December 2023. https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/refugee/procedures/07_00037.html.

———. 2023d. “難民該当性判断の手引 (Guidelines For Granting Refugee Status).” https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/001393172.pdf.

———. 2024. “ウクライナ避難民の受入れ・支援等の状況について (Current Status of Admission and Support for Ukrainian Evacuees).” https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/001388202.pdf.

Justice for Myanmar. 2023. “Statement Calling on the Japanese Government to Stop ODA and Publicly-Funded Projects Benefiting the Myanmar Military | Justice For Myanmar.” December 1. https://www.justiceformyanmar.org/press-releases/statement-calling-on-the-japanese-government-to-stop-oda-and-publicly-funded-projects-benefiting-the-myanmar-military.

Kalicki, Konrad. 2019. “Japan’s Liberal-Democratic Paradox of Refugee Admission.” Journal of Asian Studies 78(2): 355–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911819000093.

Kiel Institute for the World Economy. 2024. “Total Aid with Refugee Costs (Ukraine Support Tracker).” January. https://app.23degrees.io/view/jjk5qrNvY6pVz7qm-bar-horizontal-bar_chart_rf_total.

Ministry of Defense. 2023. “Defense of Japan 2023.” https://www.mod.go.jp/en/publ/w_paper/wp2023/DOJ2023_EN_Full.pdf.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 2024. “Japan-Ukraine Conference for Promotion of Economic Growth and Reconstruction.” February 19. https://www.mofa.go.jp/erp/c_see/ua/pageite_000001_00169.html.

Ministry of Justice. 2012. “インドシナ難民の定住許可に関する閣議了解の推移 (Successive Cabinet Approvals for Admitting Indochinese Refugees).” Cabinet Secretariat. https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/nanmin/yusikishakaigi/dai4/siryou2.pdf.

National Diet Library. 2021. “第204回国会衆議院予算委員会第4号令和3年2月4日 (The 204th Session of the National Diet, Budget Committee of the House of Representatives, No. 4, February 4th 2021).” https://kokkai.ndl.go.jp/#/detail?minId=120405261X00420210204¤t=6.

———. 2022a. “第208回国会参議院予算委員会第3号令和4年2月25日 (The 208th Session of the National Diet, Budget Committee of the House of Councilors, No. 3, February 25th 2022).” https://kokkai.ndl.go.jp/#/detail?minId=120815261X00320220225&spkNum=5¤t=159.

———. 2022b. “第208回国会参議院法務委員会第7号令和4年4月19日 (The 208th Session of the National Diet, House of Councillors Committee on Judicial Affairs No. 7, April 19th 2022).” https://kokkai.ndl.go.jp/#/detail?minId=120815206X00720220419¤t=11.

———. 2022c. “第210回国会衆議院法務委員会第2号令和4年10月26日 (The 210th Session of the National Diet, House of Representatives Committee on Judicial Affairs No. 2, October 26th 2022).” https://kokkai.ndl.go.jp/#/detail?minId=121005206X00220221026&spkNum=173¤t=23.

NHK News. 2023. “アフガニスタンから日本に避難の114人 新たに難民認定 (114 Afghan Citizens Recognized as Refugees in Japan),” July 12. https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20230712/k10014127231000.html.

Pressello, Andrea. 2023. “Japan’s Peace Diplomacy on the Vietnam War and the 1968–1969 Shift in the United States’ Asia Policy.” Japanese Studies 43(1): 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2023.2199355.

Reuters. 2021. “Japan Defence Official Warns Myanmar Coup Could Increase China’s Influence in Region.” Reuters, February 2, sec. World. https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN2A20PX/.

Seekins, Donald M. 2015. “Japan’s Development Ambitions for Myanmar: The Problem of ‘Economics before Politics.’” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 34(2): 113–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341503400205.

Shigeki, Sumi. 2022. “Japan’s Role in Ukraine from 2014-2019.” Asia-Pacific Review 29(2): 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13439006.2022.2105514.

Singh, Bhubhindar. 2024. “Front-Line Guardian of the Status Quo: Japan under the Kishida Government.” International Affairs 100(3): 1287–1301. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiae080.

Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan. 2023. “【意見】2023年入管法案に対する意見 (Opinion on the 2023 Amendment to the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act).” March 14. https://migrants.jp/news/voice/20230314.html.

Strausz, Michael. 2012. “International Pressure and Domestic Precedent: Japan’s Resettlement of Indochinese Refugees.” Asian Journal of Political Science 20(3): 244–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185377.2012.748966.

Tajima, Nobuhiko. 2023. “In Major Shift, Japan Gives Nod to Exports of Lethal Weapons.” Asahi Shimbun, December 23. https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15093193.

Tarumoto, Hideki. 2019. “Why Restrictive Refugee Policy Can Be Retained? A Japanese Case.” Migration and Development 8(1): 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2018.1482642.

UNHCR Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific. 2024a. “Afghanistan: Situation Update #32.” https://reporting.unhcr.org/afghanistan-situation-update-32.

———. 2024b. “Myanmar Emergency – UNHCR Regional Update – 5 February 2024.” https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/106848.

UNHCR Regional Bureau for Europe. 2024. “Ukraine Situation Flash Update #66.” https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/107210.

Wolman, Andrew. 2015. “Japan and International Refugee Protection Norms: Explaining Non-Compliance.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 24(4): 409–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0117196815606852.

World Bank. n.d. “Refugee Population by Country or Territory of Asylum – Canada, United Kingdom, United States, France, Italy, Germany, Japan.” World Bank Open Data. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SM.POP.REFG?end=2022&locations=CA-GB-US-FR-IT-DE-JP&start=2022&view=bar.