Abstract: In the 19th century, the massive growth of commercial whaling transformed the face of the Pacific, causing widespread ecological destruction, but also creating new links between island and shoreline communities across the region. By exploring that history from the mobile viewpoint of whaleships as they crossed and re-crossed the ocean, this essay seeks to develop a ‘liquid area’ approach to 19th century transformations in the Asia-Pacific region. Such an approach, I argue, shifts the historical focus to communities that are commonly regarded as ‘remote’ and peripheral to narratives of national history. It helps us to see how the people of these communities responded actively and creatively to the incursions of global capitalism, and how they became participants in networks of interaction and exchange which spanned the region from Chile and Peru to Hawaii, Japan, the Bering Sea coast and the many islands of Oceania.

Keywords: Pacific history; whaling; area studies

The Death of ‘Tom King’

Around three o’clock on the afternoon of 13 April 1863, a man whose name is recorded as ‘Tom King’ died in the Japanese port of Yokohama.1 King was among the first foreigners to die in the port town, which had opened its doors to the world less than four years earlier. His body was placed in a hastily-made wooden coffin and handed over the office of the US representative in Japan for burial.

But the dead man was not an American, nor a citizen of any of the western countries which had recently established relations with Japan; and his birthname was probably not ‘Tom King.” He was a Banaban, from the tiny (two-and-a-half-square-mile) coral atoll then known to Europeans as ‘Ocean Island’, which lies on the outermost western fringe of the far-flung constellation of islands that now form the nation of Kiribati, over three thousand miles to the south of Japan. Tom King had fallen ill suddenly in Yokohama, and died within a few days.2 What must it have been like to die so far from home and from anyone who spoke his native language? And did his family and friends at home ever learn what had happened to him? Perhaps not. His story may have become just one of the many swallowed up by the vastness of the Pacific.

That story, though, is part of a much larger history of the crucial ways in which whales and whaling shaped the modern history of the Pacific: for King had arrived in Yokohama as a deck-hand on an American whaleship, the Navy, which had left the Massachusetts port of New Bedford on 10 August 1859, called at Ocean Island in January 1862 and again in February 1863, and was to return to its home port on 17 April 1864 after almost five years of whaling in the Pacific and Atlantic. His shipmates—at least two of whom were women3—included Americans, a Spaniard, Portuguese from the Azores, Hawaiians, two men from the island of Niue in the South Pacific, and two from Arorae (the southernmost island of the Kiribati group).4

Whaling in the Shaping of the Modern Pacific

Between the 1820s and the late nineteenth century, whales and their hunters rewrote the geography and politics of the Pacific. Whalers were among the first colonizers of a sprinkling of small islands across the expanse of the ocean – from Lord Howe off the east coast of Australia to the Bonin (Ogasawara) Islands off Japan. Vibrant, chaotic urban communities like Honolulu and Hakodate emerged out of the vortices of the whaling economy. The search for ports where whalers could seek refuge from storms and provision their ships became a crucial element in 19th century Pacific diplomacy: most famously, perhaps, when Commodore Matthew Perry, setting off on his mission to Japan in 1853, announced to his government that, as the first step, “one or more ports of refuge and supply to our whaling ships and other ships must at once be secured.”5 Whale ships created links between improbable points on the globe: the Azores and Alaska; the Bonin Islands and Kamchatka; Banaba and Yokohama. And the history of whaling had massive environmental effects on Pacific ecologies and on the lives of indigenous communities: effects that went far beyond the decimation of whale populations themselves.

Much has been written about Pacific whaling from widely varying perspectives.6 Marine biologists and ecologists have researched changing patterns of whale migration in the Pacific Ocean7, and writers with a love of the natural environment have contemplated the entangled relationship between whales and humans.8 Historians have explored the global development of the whaling industry, and its role in the history of the major whaling nations.9 Historical studies of Pacific islands often emphasise the importance of whaling for particular island communities,10 while the recent growth of interest in oceanic history and maritime borders has evoked new interest in understanding the part that whaling has played in international diplomacy and in transnational encounters on the high seas.11 The adventure and the violence of oceanic whaling has also made it the topic of a wide range of popular history books, and, of course, novels.12

As Ryan Tucker Jones writes, “stories of inter-species relationships, illustrated particularly well with whales and humans, bring the history of the entire Pacific Ocean together.”13 Jones explores these connections by focusing on the crucial part that family and kinship play in the interwoven lives of whales and their human hunters. The voyage on which I am embarking here also follows the traces that whaling left on modern empires in the Pacific. But it is a quest above all for the distinctive (and often neglected or forgotten) geography of human and ecological connections which whales and whaling created across the Pacific region. As a historian of East Asia, I have long been interested in the notion of ‘areas’ in history. Over the past twenty or thirty years, many researchers have explored new ways to understand the intersections of space and time, and to rediscover historical processes which overflowed the mental boundaries that we conventionally draw around nations states and between regions like ‘Asia’ and ‘the Pacific,’ or between ‘East Asia,’ ‘Southeast Asia’ and ‘South Asia.’14

How can we develop historical approaches that respect the profound importance of geographical place without our view of the world being trapped in the boundaries that confined conventional ‘area studies’? One answer to that question might lie in the notion of ‘liquid area studies’—the idea that ‘areas’ come into being only as a result of human activity, such as travel, trade, and communication. “In other words, rather than being a solid thing, embedded in the bedrock of geography, an area is rather like a fountain, which is given shape only by constant activity and movement. Like a fountain too, it may radically change shape, or disappear altogether, if movement changes direction or ceases.”15

Human interaction with whales in the Pacific provides a particularly vivid example of the way in which new areas are made and unmade; and its distinctive geography uncovers aspects of history which more familiar mental maps often obscure. Whaling voyages linked places that seem remote from one another and peripheral from the vantage point of national politics. They spanned the Pacific both from east to west and from north to south, and in the process, they confute our oddly pervasive tendency to colour our images of the Pacific in tropical hues, seeing it as a place “dominated by the colour blue” and “overwhelmingly fringed with leaning palm trees and coral reefs.”16 The Pacific of whales and whaling is an ocean of ferocious gales, dense fogs and drifting ice-floes, as much as it is a seascape of palms and coral.

By looking at this fluid region, not from the land-based perspective of particular nation states or ethnic communities, but from the ever-moving perspective of ships as they sailed the Pacific in the wake of the whale, I hope that we can bring to light important human and natural connections which took shape in the nineteenth century Pacific. This perspective emerges from a rising tide of interest in the place of the sea in history—a field of research pioneered by scholars like Hamashita Takeshi,17 Anthony Reid18 and Paul D’Arcy,19 and recently given further momentum by projects based at Harvard, the National University of Singapore (NUS), and elsewhere.20 To borrow the words of NUS scholar Tim Bunnell, there is a new sensitivity to the possibilities of “non terracentric histories and geographies.”21 And yet many histories, while bringing the sea into the centre of their narratives, still view it from within the mental boundaries of a national past. Ships, of course, were not free from the constraints of the nation either. Nineteenth century whalers flew a national flag and intermittently invoked the diplomatic rules and power of their home country. But they were relatively anarchic and unusually multi-ethnic floating spaces, and their endless mobility offers a distinctive vantage point for thinking about history.

What happens when we step onto the deck of a ship, and allow it to carry us out into the winds and currents of the borderless sea? This seascape, I think, affects the way that we experience time as well as space. From within national borders, there is a tendency to see the forces of ‘modernity’ (however defined) as gradually radiating outward from metropolitan areas which are the seats of government or hubs of trade. Outer lying rural regions as seen as being only slowly exposed to these forces, while further out still, the little islands and sparsely populated areas on (or beyond) the fringes of the nation are assumed to be the most isolated and the slowest to change, and are viewed often in anthropological rather than historical terms.

But the seascape from the perspective of a nineteenth century whaler challenges that assumption. The ‘remotest’ places (in terms of conventional histories and geographies) were sometimes the spots on the map most rapidly exposed to the violence, the turbulence and the generative forces of the ‘global modern’; and their people were among the earliest to respond to those forces.

This essay joins the voyage of the whaleship Navy, which brought Tom King to Yokohama, and draws on its logbooks and on other nineteenth century accounts of Pacific whales and whaling. Through its journey, we can begin to map the distinctive web of human and inter-species connections created by the nineteenth century pursuit of whales, and to glimpse the enduring ways in which these connections shaped Pacific history. The perspective brings to the fore the people of Pacific maritime communities who were most immediately affected by global whaling capitalism. We begin to be able to see the devastating impact which that capitalism wrought on their lives, but also the energy and inventiveness with which they often engaged with the new forces shaping their worlds. Victims of exploitation and violence, they were also so much more than mere victims. They became central actors in a new web of barely visible connections that spanned the Pacific Ocean and beyond, and helped to create the modern world of the Pacific.

Before we start to look for their stories, though, we need first to sketch the world of whales from which the whaling voyages of the nineteenth-century Pacific emerged.

Whales and Humans in the Pacific

From their Eocene origins as terrestrial mammals, whales have slowly evolved into a wide range of species, each with its own cultural patterns and its own oceanic realm of mobility. Humpbacks have the one of the longest known migratory routes of any mammals, sometimes travelling as far as 5300 miles (8500 kilometres) in a single direction as they move between sub-polar summer feeding grounds and more temperate winter breeding grounds.22 By contrast, bowhead whales—which have the longest mammalian lifespan, sometimes exceeding 200 years—live and breed within the confines of arctic waters23, while sperm whales live around the equator and in the warmer regions of the south-eastern and north-eastern Pacific, and appear to migrate only quite short distances to the north or south.24 Like humpbacks, right whales—the first species to be systematically hunted by European offshore whalers—live in distinct northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere communities, and make two-way annual migrations between colder and warmer waters. Grey whales live only in the northern hemisphere, and migrate along the coast of California, Canada and Alaska in the east, and from the waters off the Korean Peninsula to the Okhotsk Sea in the west.25

Human interaction with whales is almost as old as the human encounter with the sea itself.26 At first, foraging humans used the carcasses of beached whales as sources of food, but there is good evidence to suggest that the peoples who lived around the Bering Straits were already actively hunting whales some 3000 years ago, perhaps for reason of religious ritual as well as subsistence.27 There are also indications of active whaling by the Neolithic peoples of the south-eastern coast of Korea.28 In Japan, reliable documentary evidence of organized harpoon whaling groups dates back to the second half of the sixteenth century29, and villagers in some parts of south-eastern Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu also began from the 17th century CE to use nets to help capture whales that strayed into narrow inshore bays.30 During the 18th and early 19th centuries, as Japanese cities expanded, the economy became more commercialised, and new technologies boosted the production of rice and other crops. Jakobina Arch describes how the growth of local whaling played an important role in these processes. Whales were not only a source of meat and lamp oil. Their oil and crushed bones were used as fertiliser, strips of their intestines were made into sinuous strings used in the processing of cotton, and whale oil was also sprayed on rice paddies as an insecticide.31

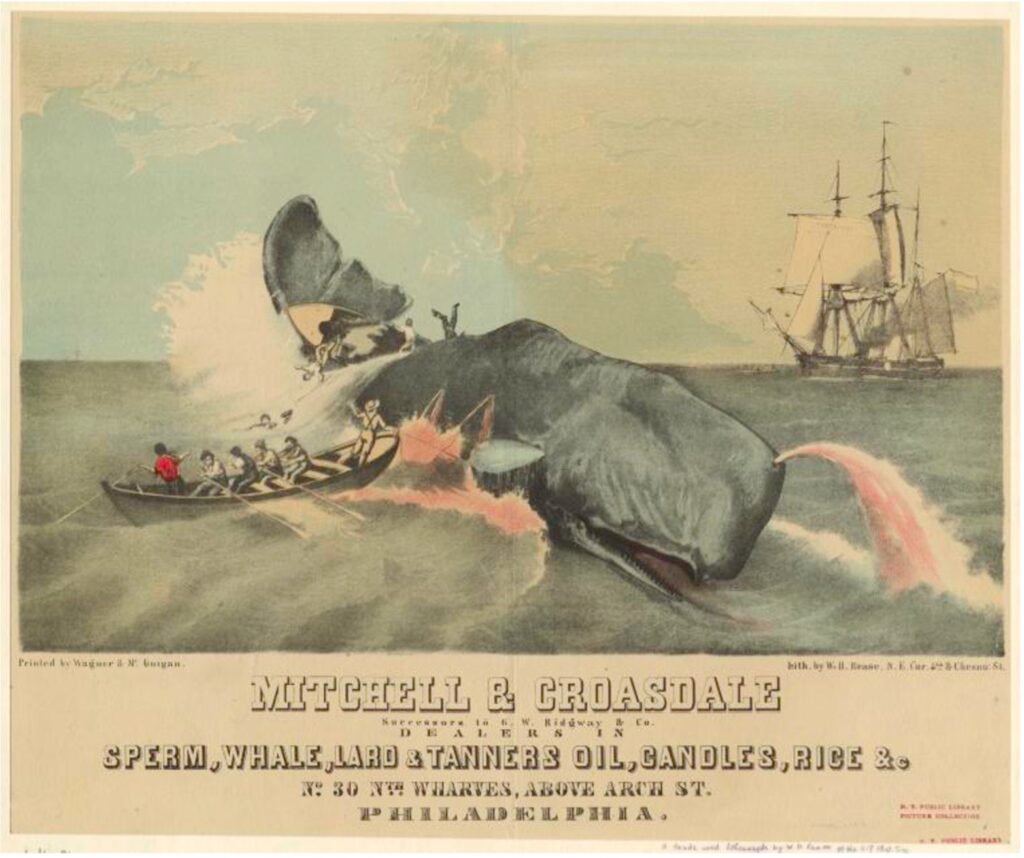

But all of this was on a scale that bore no comparison to the wave of commercial whaling that entered the Pacific from Europe and North America from the late eighteenth century onward. The early industrial era is commonly thought of as an age of coal and steam, but it was an age of oil, too: not oil drawn from the earth, but oil taken from the bodies of whales. The factories of the early nineteenth century were driven by steam, but they were often illuminated by whale oil, which also lubricated their machinery, emulsified their paint and lit the lamps in the homes of their managers and workers. From the late eighteenth century onward, spermaceti from the brain cavity of sperm whales was used to make the other main light source of the early industrial era: candles.32

Basque seafarers had pursued whales into the icy waters of the far north Atlantic as far back as the late 14th century, and British whalers are reported to have established their first base on Greenland in 1610.33 A central role in this history, though, was played by American fleets based in New England ports like Nantucket and New Bedford. By the end of the 18th century their ships, as well as others from Western Europe, were regularly rounding Cape Horn to exploit the rich whaling grounds of the Pacific. At the peak of American Pacific whaling in 1846, 729 US whalers ranged across the surface of the ocean in search of whales.34 Whaling also played a crucial part in the early colonial histories of Australia and New Zealand. Whaling fleets based in Tasmania’s Derwent River, Sydney and Twofold Bay in Australia, and at Dunedin and in the Bay of Islands in New Zealand, sailed north and east in search of humpbacks and right whales.

On a voyage which lasted from 1820 to 1822, the British whale ship Syren reported that sperm whales abounded in the vast and vaguely defined stretch of ocean which, confusingly, came to be known as the ‘Japan ground.’ This was, in fact, an expanse of ocean extending from “well northwest of the Hawaiian chain towards Japan,” and encompassing Midway Island at one extreme and the Bonin (Ogasawara) and Izu Islands east of Honshu at the other.35 Then, from 1848 onward, commercial whaling fleets extended their range northward to pursue the bowhead whales of the Okhotsk and Bering Seas and adjacent Artic Ocean, and whalers often sailed towards these waters through the sea separating Japan from the Korean Peninsula and the northeastern coast of China.36

From the late 1850s onwards, the growing use of harpoon guns and steam-powered whale ships made it easier for whalers to kill their prey, but by then other forces were foreshadowing the decline of Pacific whaling. Coal gas was already competing with whale oil as a source of lighting; petroleum and kerosene were beginning to be developed for commercial use just at the time when whaling vessels started to convert to steam power.37 The late nineteenth century fashion for whalebone corsets (actually made from baleen, usually taken from right whales) helped to keep the industry going38; but by the last decades of the century, drastic over-harvesting of whales combined with competition from alternatives to whale oil and spermaceti had opened the path to the long, slow death of Pacific whaling, a process that would continue well into the twentieth century.

The Voyage of the Whale Ship Navy

Whalers, like whales, were always on the move, migrating seasonally back and forth across vast stretches of ocean, but the hunters did not directly follow the migration paths of their prey. Instead, their voyages followed routes influenced by multiple forces: the seasonal presence of whales; the movement of sea currents and prevailing winds; and access to stopping points where ships crews could find food, fresh water, and timber for repairs.

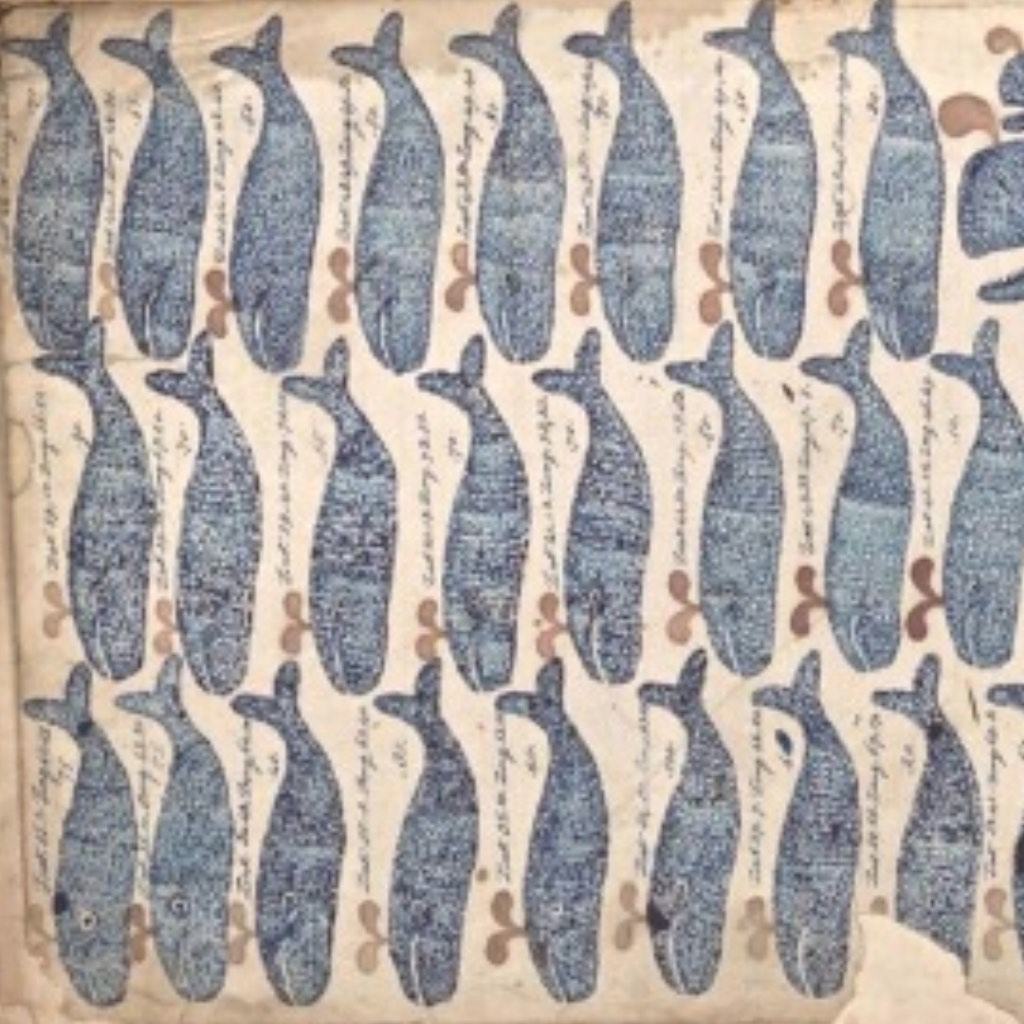

Many logbooks and journals of whaling ships in the Pacific survive. With a few interesting exceptions39, they were generally written by White men, and reflect the social positions of their authors; yet despite their limitations, they offer a vivid picture of the whaling voyages.40 The 1859‒1864 voyage of the whaler Navy is recorded in two separate logbooks, one written by the ship’s master, Andrew S. Sarvant, and the other (contained in two notebooks) begun by the Navy’s first mate, Nelson C. Haley, and then completed by his successor, John D. Dimond, after Haley (for unexplained reasons) left the ship in the Hawaiian port of Hilo. Taken together, the two sets of records offer fascinating insights into the ship’s long voyage, which involved four full years of whaling in the Pacific before the return to its home port.

I supplement information from these records with some of the rich array of paintings and drawings of nineteenth century whaling, and particularly with sections of the monumental “Grand Panorama of a Whaling Voyage ’Round the World,” a 1238-foot-long painting produced in 1848 by maritime artist Benjamin Russell and sign-painter Caleb Purington. This panorama, which was restored by the New Bedford Whaling Museum in 2018, is designed to be rolled through a proscenium—rather like a cinema screen—giving land-bound viewers the impression of travelling on a whale ship themselves.41 It was intended as a popular entertainment, rather than as a work of fine art or a scientific representation of topography. Benjamin Russell drew on his own experiences of work as a harpooner in the Pacific, and as such the itinerary of the painted voyage intersects at several points with that of the Navy. The Grand Panorama helps to bring to life the scenes briefly sketched by the terse prose of the logbooks.

Every whale ship followed its own route, but their journeys had common recurring patterns which are well illustrated by the voyage of the Navy. After leaving New Bedford for the Pacific whaling grounds on 11 August 1858, the ship sailed in a direction that might seem counterintuitive, heading first almost due east across the Atlantic to the Azores, the archipelago to the west of Portugal. There were good reasons for following this course, though, and it was the route taken by many of the Pacific whalers. The powerful current known as the North Atlantic Gyre carried ships swiftly eastward before its waters bifurcated, with its southern stream (the Canary Current) bearing ships southward towards the west coast of Africa.

The Atlantic waters between the Portuguese islands of the Azores and Madeira and the Cape Verde Islands (then ruled by Portugal, and now the Republic of Cabo Verde) were rich whaling grounds that had been exploited by New England whalers since the middle of the eighteenth century42, and the islands had ports where whale ships could take on supplies and recruit experienced crew members for the rest of the voyage. The people of the islands were mostly of Portuguese ancestry; in the Cape Verde Islands (which had been an important staging post in the slave trade) many were of mixed Portuguese and African descent. Azoreans, Madeirans and Cape Verde Islanders formed a crucial part of the crews on Pacific whaling ships.

Some of these Atlantic islanders ended up living permanently in various parts of the Pacific. By 1879, the population of Hawaii included 439 Portuguese: in the words of a contemporary report, “it can safely be said that nearly all had been sailors on board the whalers, and were mostly of the Cape Verde Islands and Madeira.”43 This Portuguese presence paved the way to a larger inflow of sugar plantation workers from the Portuguese Atlantic islands from the late 1870s onwards, and it was mid-nineteenth century migration from Madeira that brought to Hawaii the musical instrument (known in Madeira as the machete) which was to evolve into the ukulele.44

Other Madeirans, Azoreans, and Cape Verdeans ventured further into the Pacific; one of the earliest permanent inhabitants of the previously uninhabited Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands (now part of Japan) was Joachim Gonzales from the Cape Verde Islands, who arrived in the Ogasawara Islands on a British whale ship in 1831 and settled there with his Hawaiian wife.45 And around the revealingly-named settlement of Jabbertown on the west coast of Alaska, there is a still surviving group of indigenous Iñupiaq people with partly Azorean Portuguese ancestry dating back to the coming of the mid-nineteenth century whaling fleets.46

The Navy did not visit the Cape Verde Islands or Madeira, but it did stop for several days in the Azores, where it took on fresh supplies of potatoes, onions and chickens, and recruited four new crew members. One of them (who became ill during the voyage) was later left behind in Honolulu, and during its stops in the Hawaiian Islands the ship also picked up six people with Portuguese names, most likely islanders from the Azores, Madeira or Cape Verde who had arrived in the Pacific on earlier whaling voyages. From the Azores, the Navy traveled southward, parallel to the coast of West Africa, and then (still propelled by the power of the North Atlantic Gyre) crossed back across the ocean to the waters off the coast of Brazil.

On 27 October 1859, the log is marked, for the first time, with the whale stamps, indicating successful capture of two sperm whales; but it was another two months before the ship rounded Cape Horn in wild weather, and entered the waters of the Pacific. By the time they reached the South Pacific, the New England whale ships had generally been at sea for almost half a year, and were in urgent need of fresh supplies of food, water and timber (to make repairs to the ships and construct barrels for storage). Many of them therefore went into one of the ports on the east coast of Peru or Chile—with the Peruvian port of Paita being a particularly favored haven—or anchored in sheltered bays of offshore islands like Isla Mocha, to the southwest of the Chilean port town of Concepcion.

By the mid-19th century, Mocha, with its small indigenous Mapuche population, had become an important staging post for Pacific whaling: the seas around the island had been home to the famous giant white sperm whale nicknamed ‘Mocha Dick,’ whose violent death was dramatically recounted by writer Jeremy N. Reynolds in his 1839 work of the same name—a key source of inspiration for Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby Dick.47 At Mocha (as at a number of the spots where they anchored), the Navy’s captain went ashore to bargain for food, leaving the rest of the crew on the ship.

They remained in the waters off the South American coast for several weeks, catching sperm and pilot whales, before heading northwest towards Fatu Hiva (then known to Europeans as Magdalena) in the Marquesas, the Polynesian archipelago east of Tahiti. The Marquesas had recently been claimed by the French as part of their empire, and Fatu Hiva, together with the more northerly Marquesas island of Nuku Hiva, were important stopping points on Pacific whaling voyages on the route from the west coast of South America to Hawaii. At Fatu Hiva, the Navy anchored for a while, taking on fresh water and re-painting the ship.

During their stay on the island, two crew members deserted, and the Navy’s captain gave local islanders cloth and a musket in return for their help in an unsuccessful attempt to hunt down the fugitives. Another of the ship’s crew, Frank Swell, was left on the island because he was suffering from ‘the verneal’ (venereal disease).48 One cannot help wondering what happened to him, abandoned and ill on Fatu Hiva—but even more, what happened to the people of Fatu Hiva. This is just one of several references in the Navy’s logbook to venereal disease, which had already arrived with early European visitors to Tahiti49, but was spread much more widely around the Pacific by nineteenth century whalers.

In an age when Pacific passenger shipping routes were few and far between, whale ships provided an important means of transport, and quite often picked up travelers willing to work in return for food and a bunk or hammock in the ship’s overcrowded sleeping quarters. In Fatu Hiva, the Navy took on a man referred to in the ship’s log as ‘John’ or ‘Edward John’ who promised to work his passage to the Kingdom of Hawaii, just a two-week voyage northward.

Hawaiian and Japanese Vortices

The liquid area created by the whaling voyages was formed from flows—the movement of ships across water, propelled by currents, prevailing winds and the migrations of whales—but also from vortices: points on the map where these flows converged to create dense whirls of social and environmental interaction.50 With Japan’s ports still closed to outsiders until the middle of the 1850s, the Hawaiian ports of Lahaina, Honolulu, and Hilo had become the crucial vortices in the world of Pacific whaling. Here the whalers arriving from many directions would anchor and re-provision their ships in spring, before heading north for five months of whaling the icy waters of the northern seas, and here they would return, generally in October or November, on their way to the sperm whale fisheries of the equatorial regions and the South Pacific.

Albert Peck, a crew member on the New England whaler Covington, arrived in the Pacific four years earlier than the Navy and spent some time ashore in Lahaina and Honolulu. His logbook gives a vivid description of these towns, with their multiracial populations, their bowling alleys and brothels, and their grog shops from which the scratchy music of fiddlers spilled out into the street, but fell suddenly silent when the whale fleet departed for its northern hunting grounds.51 By the early 1850s, over a hundred whale ships were docking in Lahaina every year on their way to and from the northern reaches of the Pacific,52 and their visits were largely concentrated into two short periods—from March to April and from October to November—making the effect of their presence particularly overwhelming.

The Navy visited Hawaii five times during its 1859‒1864 whaling voyage, anchoring at a number of points including Honolulu and Hilo. Sometimes they stayed only a few days to take on supplies, but on other occasions (for example, from October to November 1861) they remained off Honolulu for weeks on end while the crew painted and repaired their ship and enjoyed a spell of shore leave. On every occasion, there were incidents of drunkenness and desertion: on their first visit, Edward John, the man they had picked up in Fatu Hiva, was imprisoned after he got drunk and “insulted a man’s wife” (‘insulted’, in this case, probably being a euphemism for ‘assaulted’). During the Navy’s stay in Honolulu in November 1862, a group of crew members went on strike in protest at the harsh physical punishments meted by offers out for minor offences. As generally happened in such cases, the captain called on the authority of the American Consul, who questioned the recalcitrant seamen and had one Portuguese crew member removed from the ship.

But the Navy’s voyage also coincided with the years when Japan’s newly opened ports were starting to offer attractive alternatives to Honolulu and Lahaina as ports of call between the northern and southern whaling grounds. Hakodate on the island of Ezo (now Hokkaido) had been opened to foreign vessels in 1855, and was soon rivalling the Hawaiian ports as a stopping point for American and other whalers. US Commercial Agent (and later Consul) Elisha Rice, who first arrived in the town in 1858, observed that Hakodate “reminded me more of Nantucket than any other place I ever saw.”53

Yokohama is generally thought of as a trading port, but in the years immediately after its opening to foreigners in 1859, it too was a crucial re-provisioning point for whale ships on their way north to the Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean, and its history was profoundly affected by the presence of whalers. In 1862 and 1863, the Navy stopped in Yokohama rather than in one of the Hawaiian ports to take on supplies for its northern summer whaling voyages. According to an inventory in the ship’s logbook, the crew’s purchases in Yokohama included a table, writing desks, wooden boxes, jugs, pipes, lanterns, silk thread, two swords and 88 gallons of whisky.54 During these visits, three of the ship’s crew deserted, somehow managing to survive in the challenging environment of Bakumatsu Japan until (presumably) they found a chance to board another whale ship, and (as we have seen), a fourth—Tom King—was left behind in a lonely grave.

Floating Cities

Whale ships moved around the Pacific, not as individual dots on the ocean, but in protean nomadic communities which expanded and contracted as they traveled, at times forming something that resembled a floating city. During long journeys from Atlantic and through the Pacific, two vessels would sometimes sail in convoy for several days before parting company, and passing whale ships often ‘spoke’ or ‘gammed’ with one another – exchanging information about their port of origin, incidents on their voyage, and the number of whales they had caught.

A much more concentrated whaling presence, though, took shape in the rich but perilous whaling grounds of the Sea of Okhotsk, the Bering Sea and the Arctic Ocean—between the east coast of Siberia and the Kamchatka Peninsula on one side, and the west coast of Alaska on the other. These waters were the main goal of mid-19th century Pacific whaling voyages, and here, during the summer season from late May to October, the whaling fleet moved like a great shoal, crowded in particular bays and offshores areas where whales were known to be numerous and where ships were in reach of shelter from the icy gales which swept the northern seas. The Bering/Artic waters therefore also became another vortex in the flows of whaling, but one whose nature was different from that of the port towns of Hawaii and Japan. In these far northern regions, ships remained largely offshore, and although their impact on the environment and the lives of the indigenous inhabitants was enormous, the human interaction between whalers and local people was less intense than it was in a place like Honolulu or Yokohama.

In 1860, the Navy was alone when it left Hawaii in late March to sail to the northern whaling grounds, but by the time it reached the Gulf of Anadyr in the Bering Sea on 18 June, it was in sight of thirteen other ships, all heading in the same direction.55 The whale ships gathered in the relatively protected areas around the gulf and St. Lawrence Island, waiting for the ice to clear sufficiently for them to pass through the Bering Straits into the Arctic Ocean, and ‘gamming’ about the weather and sea conditions. Then in July they sailed through the Bering Straits into the Arctic Ocean, trying to stay close to the edge of the icepack, where bowhead whales could most commonly be found, without actually becoming trapped by the ice.56 During this most dangerous part of the voyage, the Navy’s navigators made sure to remain in sight of a companion ship that could help keep watch for whales and might act as a rescue vessel in case of disaster.

It is not clear how many ships were in the region during the Navy’s 1860 whaling voyage, but in 1850, almost 150 ships had congregated there during the summer whaling season, and in September to October 1854, 129 of the whale ships entering the port of Lahaina alone had arrived from the Okhotsk, Bering, and Arctic whaling grounds.57 Many ships had crews of thirty or more people, so the temporary communities formed by this fleet of ships in the summer months of the 1850s and early 1860s had populations of several thousands. Latecomer vessels provided a kind of postal service for this floating city, carrying letters and parcels which they had collected in Hawaii, and which they delivered to the ships which had arrived in the north before them.58

The Chukchi and Yupik people who lived on the Asian shores of the Bering Straits and on islands in the Bering Sea, and the Iñupiaq who lived on the Alaskan shores, all relied on whale hunting for survival and for important cultural practices. Whale meat was carefully preserved in permafrost; blubber was used for lighting lamps; skin and intestines provided waterproof clothing and covering for tents and boats; and bones could be used for house frames.59 At the time of the coming of the Pacific whaling fleet, these were not isolated communities encountering the outside world for the first time: their lives had already been disrupted by often violent encounters with the expanding Russian empire.60 But the sudden appearance of thousands of alien whale hunters in the midst of their waters deepened the crisis into which their societies had already been thrown.

The crews of American and other whale ships sometimes landed and camped on shore, particularly in the Gulf of Anadyr, seeking water and timber and boiling down whale blubber for oil (a process with created large amounts of waste and significant ecological harm). The crew of Navy did not go on land, but they remained close to the shore throughout their whaling seasons in the Bering Sea, and traded with local people who paddled out to their ship in canoes.

By early October, the whalers were heading south through the Bering Sea again, and after re-provisioning (usually in one of the Hawaiian ports) the floating city dispersed across the vast expanse of the South Pacific, where the ships spent the ‘off season’ (from November to April) in search of sperm whale. In the latter part of its 1860 whaling season, the Navy—after just a couple of days at anchor off Honolulu—set its course towards the island of Niue (which the whalers called Savage Island), and then onward via Raoul Island (Sunday Island) in the Kermadec group to the North Island of New Zealand.

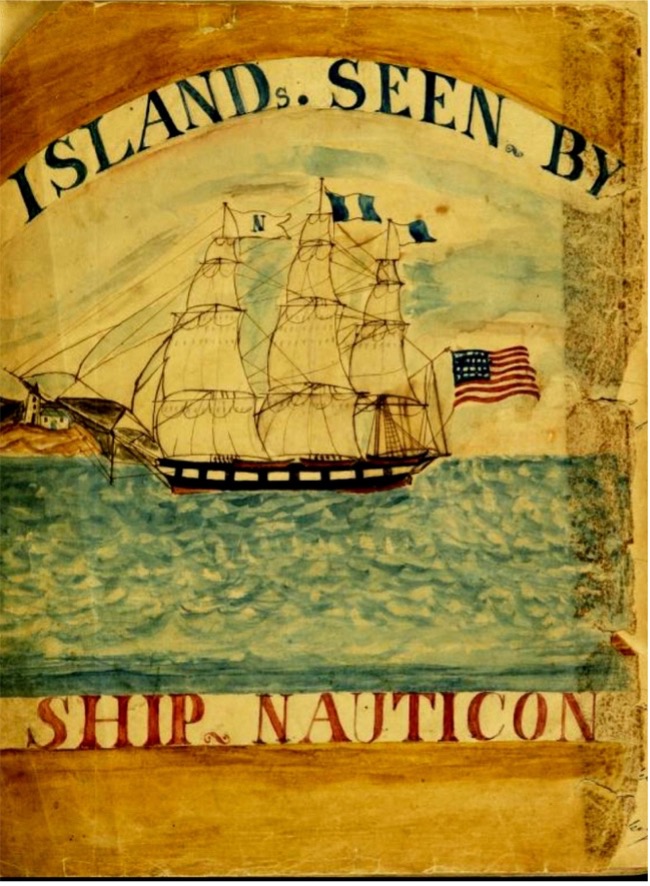

In its four off seasons in Pacific, the Navy visited several Kermadec Islands; Nauru (known to the whalers as Pleasant Island); Arorae (Hope Island), Nikunau (Byron Island), Beru (Francis Island), Tamana (Rotcher Island) and Banaba (Ocean Island, or Ocean High Island), all in what is now the nation of Kiribati; Pohnpei (Ascension Island) and Mokil Atoll (Wellington Island) in the Caroline Islands (now part of the Federated States of Micronesia); Saipan and Guam; Anahatan in the northern Marianas; Chichijima in the Bonin (Ogasawara) Islands, which had just been claimed by Japan; and Rarotonga in the Cook Islands, which in December 1863 was the ship’s last Pacific Island stopping point before they sailed back around the Horn and home to New Bedford.

This litany of islands—together with others such as Rota, Tinian, Tahiti and Nuka Hiva—recurs in the logbooks of the mid-nineteenth century whalers. In the 1980s, Pacific historian Robert Langdon produced a remarkably detailed list of South and Central Pacific ports and islands where ships from New England ports (almost all whalers) anchored on their nineteenth-century voyages. This shows (for example) 189 visits by New England ships to Arorae between 1825 and 1879, and 277 visits to Banaba between 1832 and 1904, the largest number occurring in the 1850s to 1870s.61 Relatively isolated islands like these were close to rich whaling grounds, and the small and largely autonomous communities which lived there had few defences to stop whalers from helping themselves to whatever they found ashore.

Primitive Extraction

In these journeys, we can see an emerging pattern: massed incursions into Hawaiian and later Japanese ports in May and October–November, and into the Okhotsk, Bering, and Artic waters in the months between; then, more scattered forays by individual ships into the seas surrounding South Pacific islands between December and April. Larger-scale studies are still needed to create a more precise and detailed image of that pattern and the way it changed over time. We need, in this sense, something like the process described in information studies as ‘primitive extraction’: a process of picking out the basic geometric shapes which underlie the complex mass of spatial information generated by many overlapping voyages.

But for now, I would like to consider what this pattern of voyages meant for the local people of the regions drawn into the far-flung net of Pacific whaling; and here, the starting point is ‘primitive extraction’ in a very different—economic and ecological—sense of the word. Whalers plundered both ocean and land resources in their pursuit of the liquid treasure of whale oil. In the early stages, this plunder was often completely one-sided: resources were seized from sea and earth with no recompense. One of the reasons why small islands were such popular stopping places was precisely because they were the places where non-reciprocal plunder was easiest. But these local communities reacted and sometimes resisted, in the process helping to create more complex commercial and human relationships between commercial whaling and a multitude of Pacific societies.

Most simply and obviously, whalers plundered whales. A careful study of the number of Pacific whale sightings reported in American whalers’ logbooks shows a very sharp drop in reported sightings of sperm and right whales between the period 1825‒1849 and the period 1850‒1874, and a similar decline in grey and bowhead whale sightings between 1850‒1874 (the era which covered the emergence and rise of Pacific bowhead whaling) and 1875‒1920. This second decline can partly be explained by the shrinking size of the Pacific whaling fleet, as demand for whale oil fell, and of course the logbooks themselves are not wholly reliable records. The scale of the recorded slump in sightings, though, is great enough to indicate a major impact on whale populations, some of which have not yet recovered to their levels in the era before the start of large-scale Pacific whaling.62

Like humans, whales and other species also responded and adapted to the presence of large-scale whaling. Slow moving bowhead whales, which had been relatively easy for the indigenous people of the Bering Sea region to hunt, became more wary of the presence of boats: “Bowheads now identified whaleboats by sight; as a log keeper noted after a failed chase, the ‘Whale saw the boat and rolled away.’”63 Whale ships like the Navy also hunted other marine mammals including walruses64: crucial parts of the economic and cultural lives of the peoples of the Bering Sea. By the 1880s, according to a contemporary observer of life in Alaska, foreign whalers had “practically driven the walruses from the shore, and greatly reduced the numbers of hair seals and whales. Thus, all the supplies of food have been curtailed.”65

The whalers’ processes of primitive extraction had a huge impact on many other Pacific resources too. Even a brief visit by single ship like the Navy could leave a mark on the landscape and population of a very small island. On just one of their stops at the island of Nikunau—an inhabited atoll with an area of just over seven square miles—the crew of the Navy came away with four canoe-loads of wood and about 2000 coconuts; and at Almagan Island in the Northern Marianas (total size, about five square miles) the captain went ashore to trade and acquired a haul of about fifty pumpkins and another 2000 coconuts.66 Coconuts were an essential source of food and drinking liquid throughout these islands, while their shells were used as cups and other containers. Such sudden and large-scale depletions a vital source of liquid and nutrition must have had an unsettling impact on the livelihood of the community.

Violence and Retaliation

The potential consequences of the most extreme forms of early nineteenth-century non-reciprocal plunder are well illustrated by the haunting story of the voyage of Australian whale ship (and former convict transport ship) Lady Rowena, whose 1830 to 1832 whaling expedition resulted in the first major encounter between Australia and Japan. The ship, captained by Bourn Russell (who later went on to become a New South Wales politician) left the port of Sydney on 2 November 1830 for a voyage to the recently ‘discovered’ whaling grounds off the northern coasts of Japan. The ship’s crew landed at Cape Kiritappu, on the east coast of the island now known as Hokkaido (then known in Japanese as Ezo) where they planned to re-provision their vessel and survey the coastline. This was a region inhabited by Ainu people who lived in self-governing villages, but it was also an area where the Japanese domain of Matsumae was exerting increasing influence over the lives of the Ainu inhabitants.

After an initially friendly exchange of goods between the whalers and Ainu of the village of Urayakotan, the local people became alarmed at the presence of the outsiders, and fled to the hinterland, taking much of their stored food with them. The crew of the Lady Rowena proceeded to loot the village, seizing not only necessary provisions like salt and firewood, but also other household items: Bourn Russell, for example, removed the family shrine (kamidana) from the house of one of the Japanese inhabitants of the region.67 They then burned much of the village to the ground (accidentally, according to Russell’s account) and kidnapped one Japanese and one Ainu man, whom they took to their ship in an unsuccessful effort to extract information about the area from them, though both were later released.68

This so alarmed Matsumae Domain that it sent a substantial force of around forty to fifty armed and mounted men to confront the intruders. A skirmish between the whalers and the Matsumae troop resulted in the retreat of Lady Rowena, which sailed out to waters off the east coast of Honshu, and went on to land on the small Japanese island of Hachijojima before sailing southward. The incident led the Domain of Matsumae to reinforce its military presence on Cape Kiritappu to ward off future incursions by foreign ships.69

Despite this experience, the Lady Rowena continued its predation elsewhere. After cruising through the South Pacific in search of whales, the ship anchored off the south coast of island of New Britain (Niu Briten, now part of Papua New Guinea). When local villagers refused the whalers’ attempt to exchange pigs (crucial items of their wealth) for blue beads, the crew fired their guns at one of the pigs, and continued to fire on the villagers who fled into nearby bushes.70 Soon after, near the south-coast settlement of Wowonga, the captain and some other crew members set off for shore in some of the ship’s boats, and encountered islanders approaching them in canoes and making gestures which Russell interpreted as being hostile. The whalers fired at the local people, killing several, including a local chief, and wounding many others. Their shipmates who had remained on board the Lady Rowena also fired on canoes which had gathered close to the ship, despite the fact that the islanders had made no attempt to board the whaler.71 Again, a substantial but unknown number of local villagers were killed. Bourne Russell claimed that the killings had been acts of self-defense from attacks by the ‘savage’ warriors.

But Russell had a very fractious relationship with his crew, some of whom later refused to obey his commands and were put off the ship on a small island in the Tonga group. After arriving back in Sydney, two of these eyewitnesses to the New Britain killings (a cooper and a boatsman from the Lady Rowena) gave sworn testimony which was submitted to the governor of New South Wales, and which flatly contradicted Russell’s account. The two men testified that the local villagers’ canoes had been far from the ship and no threat to the crew when the Lady Rowena’s crew opened fire, killing and wounding many islanders, including the village chief. Captain Russell (they reported) had also seized an injured youth and taken him away on the ship, ignoring the pleas of a man whom the witnesses assumed to be the young man’s father.72

Events like these provoked Pacific Islanders to fight back. About two months after the New Britain killings, another violent incident, in which the Lady Rowena was also peripherally involved, occurred off Wallis Island (now part of the French overseas territory of Wallis and Futuna): the crew of the British whaleship Oldham forcibly abducted and raped island women, and looted mats, bark-cloth and other items from village houses. The Oldham’s captain (who was frequently drunk) also threatened to shoot the local chief. Some of the islanders responded by boarding the ship armed with spears and machetes, and killed its entire crew except for one young English seaman who was rescued and briefly adopted by a local chief.73 The crew of the Lady Rowena, which arrived on the scene just after the killings, investigated and learnt of the Oldham captain’s death and the capture of ship by New Britain islanders. They fired their guns at the Oldham in an unsuccessful attempt to retake the vessel before sailing on to their next destination.74

The response of other European and American seafarers to news of this violence was telling and, in some ways, rather surprising. There was some talk of the need to “chastise” the “savages,”75 but this was more muted than the outspoken denunciation of the crews of the Lady Rowena and Oldham for provoking the anger of Pacific Islanders, and so increasing the dangers faced by future whaling voyages which would follow in their wake. A young British whaler named Robert Jarman who came to know former crew members of the Lady Rowena and evidently heard these stories them, wrote in the published journal of his travels:

the cruelties that the Lady Rowena’s crew were guilty of, when cruising off New Britain, without the least pretence, were the most revolting and inhuman I have ever heard of. It cannot be supposed that the inhabitants of these places will neglect to retaliate, the first opportunity they have it in their power.76

The Wallis Islanders’ attack on the Oldham, Jarman observed, should “serve as a lesson to sailors, to treat the natives they may be trading with, with humanity and kindness; especially when we consider how often by shipwreck, they are made dependent upon them for life and subsistence.”77 Similar concerns were expressed by British seafarer Price Blackwood, who interviewed the Lady Rowena’s cooper and boatsman about the New Britain killings.78

The crew of the British naval vessel Zephyr, which sailed to Wallis Island to investigate the Oldham violence, initially clashed with the islanders and killed several of them; but after entering into negotiations with a local elder and hearing about the background to the attack on the Oldham, one of the Zephyr’s officers described the behaviour of the whalers as “lawless and unjustifiable,” and commented that “it ceases to be a matter for surprise that the islanders had recourse to so severe a retaliation”.79 Whalers and other foreign seafarers in the Pacific were discovering from experience the reality of their own vulnerability and of their dependence on the communities that they visited, and the need for skills of negotiation and communication to survive in the complex world through which they navigated.

Pacific Traders and Travelers

As Lynette Russell emphasizes in her study of the role of Australian Indigenous people in the Pacific whaling fleet, it would be a mistake to think of Pacific Islanders simply as hapless victims of predatory whalers. The intrusions of American and European whalers into their lives were uninvited and often very unwelcome, but local communities responded to the threats and opportunities presented by the coming of the whale ships: occasionally with violence, but much more often with determination and ingenuity. Like Aboriginal Australians in their encounters with large-scale whaling, others too “acted and reacted, sometimes they made unexpected choices and decided to sail the world’s oceans, moving between their own native worlds and the world of nineteenth century European colonialism.”80

Evidence from the whalers’ logbooks suggests how Pacific Islanders actively expanded their commercial relationships with visiting ships. By the mid-nineteenth century, many communities were producing items like hats and matting, as well as livestock and crops, to sell to whalers in return for such things as tobacco, iron tools, and sometimes even boats. At the islands where the whaleship Navy anchored, local people often came out in canoes to trade, sometimes traveling considerable distances to do so. During the ship’s seasons in the Bering Sea, the first mate’s log refers repeatedly to “the natives” being on board to trade81, and similar trading encounters recurred throughout the South Pacific.

In February 1863, when the Navy was still some fifteen miles from Nauru, four canoes with about thirty Nauru islanders and two “Europeans” sailed out to the ship from the island, bringing pigs which they sold to the Navy’s crew in return for an old ship’s boat. As often happened during such visits, the Nauru traders stayed on the Navy overnight, sleeping in the ship’s hold before returning to their island in the morning.82 Later in the same month, off the island of Pohnpei in the Caroline group, islanders came to the ship to trade turtle shells for tobacco.83

Off Arorae, the Navy’s captain had an encounter which suggests that some Pacific island traders had firm ideas about the value of their wares. A group arrived from the island in three canoes, bringing coconuts and woven mats and “saying there was plenty of chickens and hogs and if we would lay off until morning they would fetch them… they wanted thirty lbs of tobacco for a hog that would weigh 100 lbs I bought one and two chickens and a few mats.”84 Here, as at Nauru, the island traders were accompanied by a smaller number of “Europeans”—who may have been former whalers themselves. Some of the earliest large-scale commercial ventures in the islands were started by men like Ichabod Handy, a New England whaler who, in the early 1850s, branched out into trading coconut oil in Arorae and nearby islands.85

Pacific Islanders also took advantage of the transport provided by New England whaling ships. A dramatic example of this was recorded by the first mate of the Navy in January 1863, when the vessel gave a ride to about 150 Tamana islanders, who were fleeing from their own island to Arorae (just over fifty miles away), apparently to escape some unexplained ecological disaster: the log book describes the Tamana islanders as “being in a starving condition.”86

The apparently simple distinction between mobile alien whalers and the static ‘locals’ is, of course, complicated by the fact that a number of the whalers (like Tom King, who died in Yokohama) were themselves Pacific islanders. The Navy needed a steady supply of new recruits to replace the twelve sailors who deserted during the voyage and the eleven who were officially discharged in Hawaii, and the logbook suggests that they had little difficulty finding Pacific Islander volunteers who chose to join them, perhaps for that mixture of motives that drove most participants in whaling voyages: a desire to see the world, the hope of sharing in the wealth earned by the spoils of whaling, and (in some cases) the need to escape troubles at home.

At Niue in November 1860, the captain records:

Several canoes came of [sic] with some chickens and pigs a few bananas. The natives appears to be very friendly and there are several missionaries on the Island we had several natives on board overnight… Took two natives from the island on they begged me to take them.87

And in January 1863, at Arorae, after the Navy’s large group of Tamana islander passengers had disembarked, the first mate writes that they recruited two Arorae islanders as crew members, “they wanting to join the ship.”88

These were not the first recruits from Arorae. Another man from the island—unimaginatively named in the logbook as “Hope Kanaka from Hope Island”—had joined the crew in December 1861, and was landed back at his home by the Navy late in 1862, after an exhausting but adventurous year spent travelling to Nauru, Saipan, Japan, the Bering Sea, the Arctic Ocean, and the ports of Hilo and Honolulu. A year later at Nikunau (like Arorae, now part of Kiribati), two local islanders disembarked from the ship, one having spent the previous year working as a crew member, while the other had been staying for a while in Hawaii and had joined the ship in Honolulu for the passage home.89 Some of the Pacific Island mariners, though, ended up very far from their native islands. For example, two men from Arorae (probably the pair who had joined the ship in 1863) remained on board until the Navy was about to embark on its return voyage to the US, but then asked to be left on the island of Rarotonga (over 1,500 miles from their home), “they choosing to go ashore at this island rather than go to America.”90

Māori sailors were particularly crucial to south Pacific whaling, often joining American and British as well as New Zealand and Australian ships. A tragic sign of the Māori presence comes from the story of the Oldham: the list of victims of the ship’s destruction names the sixteen British dead, but ends with five unnamed New Zealanders (meaning Māori91). Four of them, the report tells us, had attempted to desert the ship in Wallis Island, but had apparently been captured by their crewmates and brought back to the ship just before the attack, in which all were killed. Other Māori whalers fared better. Robert Jarman, writing in the 1830s, commented on “the great many [Māori] New Zealanders belonging to many ships” whom he encountered in Sydney, and added, “I know a New Zealander, who is now second mate of the Stanthorpe whaler, sailing out of Sydney. Those who have sailed with him, give him an excellent character, both as a whaler and officer. He can read and write English fluently.”92

Elsewhere in the Pacific, there were more organized official attempts to make the most of the possibilities offered by the visits of American and European whalers. In Japan, during the dying days of the Tokugawa Shogunate, the Shogunal government entered into formal agreements which enabled young Japanese men to be trained in western whaling techniques by serving apprenticeships on American and Prussian whaling vessels. In the end, only eight men took part in this scheme, but they became some of the first Japanese for centuries to travel the Pacific with the official blessing of the authorities.93

The impact of the Pacific whaling fleet, then, was complex and multi-dimensional: like many forms of globalization, it involved moments of overt and extreme violence, but it also generated exchanges of products and knowledge which influenced the daily lives of those on both sides of the exchange. The relationship between the incoming whalers and local islanders was always unequal, but it was also always complex and dynamic. It brought Pacific Islanders into contact with Spaniards, Portuguese from the Azores and Madeira, Cape Verde Islanders, Native Americans and others; but most important of all, perhaps, it connected them to one another—creating long threads of transport and human movement between far-flung islands across the Pacific.

Another Map of the Pacific

An English magazine article published in 1820 introduced its readers to the value and importance of the Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands, whose existence had only recently become known to Europeans: “These islands,” it proclaimed, “may become very useful and important to Kamchatka.”94 Most present-day readers would probably find this statement mystifying, and be inclined to assume that the author of the article had very a hazy grasp of Pacific geography. What significance could this tiny group of subtropical islands, which now marks the southeasternmost limits of Japan, have for a peninsula on the extreme northeastern fringe of Siberian Russia? But viewed from the deck of a nineteenth-century whaler, the importance of the Bonins for Kamchatka would have been so obvious as to need no explanation. These were two crucial and increasingly connected junctures in the far-flung, constantly evolving, network-shaped region which constituted the realm of Pacific whaling.

By the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the long threads of this network were rapidly fraying, as the global whaling industry entered its phase of decline, and a new world of empires and nation states was taking shape. The Bonins and Kamchatka became again widely separated spots on the map, divided by distance and political borders. But the traces left by the nineteenth century realm of Pacific whaling persist to the present day. Many of the traces are scars: marks gouged by profound damage to ecosystems and human societies. Some connections, though, were generative, producing new indigenous enterprises and new meetings and exchanges of knowledge between the peoples of the Pacific.

By following the flows which wove the world of Pacific whaling into an evanescent region, we can rediscover long-forgotten histories, and reconsider pre-existing images of ‘area’ and ‘modernity’ in this fluid world. Here, the mental divisions between Asia, Oceania, and South America are crossed by the thousands of thin lines traced in the sea by the voyages of the nineteenth century whaleships. Here, the forces of global capitalism do not ripple out smoothly from metropoles to peripheries, but erupt in the most unexpected places, shaped by the actions of people from islands and shoreline settlements whose names remain invisible on most maps of world history. Such voyages can help us to recover the stories of the Tom Kings of the world: the Azoreans and Cape Verde Islanders, the Māori and Indigenous Australians, the Ainu and Iñupiaq, the Nikunau and Arorae Islanders and Banabans, and a multitude of others whose initiative and sufferings helped to make the modern Pacific.

Acknowledgements

My enduring gratitude goes to the late Dr. Youn Min Park, whose enthusiastic research assistance helped me embark on this project. Many thanks too to Dr. Shinnosuke Takahashi for his perceptive comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this essay.

Works Cited

“Gilman & Co., Ship Chandlers and General Agents, Lahaina, Maui, S.I. – Ships Supplied with Recruits, Storage and Money.” Digitised on Archive.org, https://archive.org/details/GilmanShipsSupplied/page/n3/mode/2up (accessed 29 November 2023).

“Massacre of the Crew of the Ship Oldham by the Natives of Wallace Island.” The Nautical Magazine, July 1833, p. 376-383.

Ackerman, Robert E. “Early Maritime Traditions in the Bering, Chukchi and East Siberian Seas,” Arctic Anthropology, vol. 25, no. 1, 1988, pp. 52‒79.

Aldrich, Herbert L. Arctic Alaska and Siberia, or Eight Months with the Arctic Whalemen. Chicago and New York, Rand, McNally and Co. 1889.

Appadurai, Arjun. Globalization. Durham NC, Duke University Press, 2001.

Arch, Jakobina K. Bringing Whales Ashore: Oceans and the Environment in Early Modern Japan. Seattle, University of Washington Press, 2018.

Bosworth, Allan R. Storm Tide. New York, Harper and Row, 1965.

Braithwaite, Janelle E., Jessica J. Meeuwig, and Matthew R. Hipsey. “Optimal Migration Energetics of Humpback Whales and the Implications of Disturbance,” Conservation Physiology, vol. 3, no. 1, 2015, https://academic.oup.com/conphys/article/3/1/cov001/2571222 (accessed 4 November 2023).

Brandligt, C. Geschiedkundige Beschowing van de Walvisch Vischern. Amsterdam, T. Nusteeg, 1843.

Chapman, David. The Bonin Islanders, 1830 to the Present: Narrating Japanese Nationality. Lanham NJ, Lexington Books, 2016.

Cholmondeley, Lionel Berners. A History of the Bonin Islands from the Year 1827 to the year 1876. London, Constable and Co.

Clark, Laura. “How a 200-Year-Old Whale Might Help us Live Longer.” Smithsonian Magazine, 6 January 2015, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/how-200-year-old-whale-might-help-us-live-longer-180953813/ (accessed 4 November 2023).

Clarke, Robert. “Open Boat Whaling in the Azores: The History and Present Methods of a Relic Industry.” National Institute of Oceanography Discovery Reports, 1954, pp. 283‒354.

Colwell, Max. Whaling Around Australia. Adelaide, Rigby, 1969.

Creighton, Margaret S. Rites and Passages: The Experience of American Whaling, 1830‒1870. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

D’Arcy, Paul and Lewis Mayo. “Fluid Frontiers: Oceania and Asia in Historical Perspective.” Journal of Pacific History, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 217‒235.

D’Arcy, Paul. The People of the Sea: Environment, Identity and History in Oceania. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 2006.

Demuth, Bathsheba. “Whale Country: Bering Strait Bowheads and their Hunters in the Nineteenth Century.” In Ryan Tucker Jones, and Angela Wanhalla, eds. Across Species and Cultures: Whales, Humans and Pacific Worlds, pp. 147‒159. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 2022.

Demuth, Bathsheba. The Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait. New York, W. W. Norton, 2020.

Drew, Joshua et al., “Collateral Damage to Marine and Terrestrial Ecosystems from Yankee Whaling in the 19th Century”, Ecology and Evolution, vol. 6, no. 22, 2016, pp. 8181‒8192.

Dickens, Charles. “Black-skin A-head.” Household Words, no 146, 8 January 1853, pp. 399‒404.

Eschner, Kat. “The Real-Life Whale that Gave Moby Dick his Name.” Smithsonian Magazine, 18 October 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/real-life-whale-inspired-moby-dick-180965282/ (accessed 21 November 2023).

Forsyth, James. A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia’s North Asian Colony, 1581‒1990. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp. 149‒153.

Foster, Honoré. More South Sea Whaling: A Supplement to the South Sea Whaler. Canberra, Australian National University, 1991.

Foster, Honoré. The South Sea Whaler: An Annotated Bibliography of Published Historical, Literary and Art Material Relating to Whaling in the Pacific Ocean in the Nineteenth Century. Sharon, Mass., Kendall Whaling Museum and Fairhaven Mass. E. J. Lefkowicz, 1985.

Francis, Daniel. A History of World Whaling. Markham and New York, Viking, 1990.

Griggs, Rebecca. Fathoms: The World in the Whale. New York and London, Simon and Schuster, 2020.

Hamashita Takeshi. “’Umi’ kara Ajiaron ni Mukete,” in Omoto Keiichi ed., Umi no Ajia 5: Ekkyō suru Nettowāku. Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten, 2001.

Hamashita, Takeshi (ed. Linda Grove and Mark Selden). China, East Asia and the Global Economy: Regional and Historical Perspectives. Abingdon, Routledge, 2008.

Hawks, Francis L. and Sidney Wallach, ed. Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan under the Command of Commodore M. C. Perry, United States Navy. New York, Coward-McCann Inc., 1952.

Howell, David. “Hollow Boats and Castaways: Three Anecdotes on the Way to a New Perspective on Early Modern Japan in the Pacific.” Presented in the online roundtable “Oceanic Asia: Global History, Japanese Waters and the Edges of Area Studies,” National University of Singapore Asia Research Institute, 5 October 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ywIIWC2RmNc (accessed 13 January 2024).

Huebner, Stefan. “Asia’s Oceanic Anthropocene: How Political Elites and Global Offshore Oil Development Moved Asian Marine Spaces into the New Epoch,” Journal of Global History, vol. 18, no. 1, March 2023, pp. 25-46.

Huebner, Stefan. “The Platform Archipelago: Islands of Multispecies Adaptation Beyond a Terrestrial Worldview.” Presented in the online roundtable “Oceanic Asia: Global History, Japanese Waters and the Edges of Area Studies,” National University of Singapore Asia Research Institute, 5 October 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ywIIWC2RmNc (accessed 13 January 2024).

Huggan, Graham. Colonialism, Culture, Whales: The Cetacean Quartet. London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Jarman, Robert. Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas in the “Japan” Employed in the Sperm Whale Fishery, Under the command of Capt. John May. London, Longman and Co and Charles Tilt, c. 1838.

Jones, Noreen. North to Matsumae: Australian Whalers to Japan, Perth, University of Western Australia Publishing, 2008

Jones, Ryan Tucker, and Angela Wanhalla, eds. Across Species and Cultures: Whales, Humans and Pacific Worlds. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 2022.

Jones, Ryan Tucker. “Leviathan’s Families: The History of Humans and Whales in the Pacific,” in Ryan Tucker Jones, Matt K. Matsuda and Paul D’Arcy eds., The Cambridge History of the Pacific Ocean: Volume 1 – The Pacific Ocean to 1800. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2023, pp. 46‒90.

Josephson, Elizabeth, Tim D. Smith and Randall Reeves. “Historical Distribution of Right Whales in the North Pacific.” Fish and Fisheries, vol. 9, 2008, pp. 155‒168.

Kalland, Arne and Brian Moeran. Japanese Whaling: End of an Era? London, Curzon Press, 1992.

Kang, Bong W. “Reexamination of the Chronology of the Bangudae Petroglyphs and Whaling in Prehistoric Korea: A Different Perspective.” Journal of Anthropological Research, Winter 2020, pp. 480‒506.

Kent, Noel J. Hawaii: Islands Under the Influence. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 1993.

Kreitman, Paul. Japan’s Ocean Borderlands: Nature and Sovereignty. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Langdon, Robert. Where the Whalers Went: An Index to the Pacific Ports and Islands Visited by American Whalers (and Some Other Ships) in the 19th Century. Canberra, Australian National University Pacific Manuscripts Bureau 1984.

Letter from Price Blackwood to Major General Bourke, 5 July 1833, archival document held in the State Library of New South Wales, call no. DLSPENCER 195, section a.

Logbook of the Alice Frazier (Bark), of New Bedford, Mass., mastered by Daniel H. Taber, on voyage from 10 Sept. 1851-5 Sept. 1855, kept by Benjamin F. Pierce, New Bedford Whaling Museum logbook collection, available on the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/alicefrazierbark00alic (accessed 30 October 2023).

Logbook of the Eliza F. Mason out of New Bedford, Mass, mastered by Nathanial H. Jernigan, log kept by Orson F. Shattuck, 2 December 1853‒10 April 1857, New Bedford Whaling Museum logbook collection, available on the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/logbookofelizafm00unse (accessed 9 December 2023).

Logbook of the Navy (Ship) out of New Bedford, Mass., mastered by Andrew S. Sarvent, kept by Andrew S. Sarvent on voyage 10 Aug. 1859-18 Apr. 1864; New Bedford Whaling Museum logbook collection, available on the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/logbookofnavyshi00navy (accessed 30 October 2023).

Logbook of the Navy (Ship) out of New Bedford, Mass., mastered by Andrew S. Sarvent, kept by Nelson C. Haley and John D. Dimond on voyage 10 Aug. 1859-18 Apr. 1864, New Bedford Whaling Museum logbook collection, available on the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/logbookofnavyshi00unse (accessed 20 October 2023).

Logbook of the Navy (Ship) out of New Bedford, Mass., mastered by Andrew S. Sarvent, kept by John D. Dimond, New Bedford Whaling Museum logbook collection, available on the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/odhs-536 (accessed 20 October 2023).

Logbook of the voyage of the whale ship Covington out of Warren, Rhode Island, 1856-1860, written by Albert F. Peck, https://archive.org/details/covingtonbarkout00covi/page/102/mode/2up, (accessed 25 November 2023), pp. 63, 103 and 126‒127..

Logbook of the whale ship George Washington out of Wareham, Mass., master Benjamin F. Gibbs, 17 Nov. 1847 – 17 March 1850, https://archive.org/details/georgewashington00geor_2 (accessed 13 January 2024).

Macdonald, Barrie. Cinderellas of the Empire: Towards a History of Kiribati and Tuvalu. Suva, University of the South Pacific, 2001.

Marques, A. “Portuguese Immigration to the Hawaiian Islands.” In Thomas G. Thrum ed., Hawaiian Almanack and Annual for 1887: A Hand Book of Information, Honolulu, Press Publishing Company, 1886, pp. 74‒78.

Martin, Stephen. The Whales’ Journey: A Year in the Life of a Humpback Whale and a Century in the History of Whaling, Sydney, Allen and Unwin, 2001.

Matthews, L. Harrison. The Natural History of the Whale. New York, Columbia University Press, 1978.

Mawer, Granville Alan. Ahab’s Trade: The Saga of South Seas Whaling. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1999.

McCormack, Donna and Carey Robson. Ethnicity, National Identity and “New Zealanders”: Considerations for Monitoring Māori Health and Ethnic Inequalities, Wellington, Te Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pōmare, 2010.

Melville, Herman. Moby Dick or the White Whale. New York, Harper Brothers, 1851.

Mesfin, Isis, et al. “An Overview of Stranded Cetacean Scavenging in Atlantic Southern Africa since the Earlier Stone Age.” Les Nouvelles de l’Archéologie, no.66, 2021, pp. 64‒69, https://journals.openedition.org/nda/13532?lang=en (accessed 4 November 2023).

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. “Liquid Area Studies: Northeast Asia in Motion as Viewed from Mount Geumgang.” Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique, vol. 27, no. 1, February 2019, pp. 209‒239.

Morton, Harry. The Whale’s Wake. Dunedin, University of Otago Press, 1982.

Murakami Yūichi. “Ōsutoraria no Hogeisen to Nihon, 1954-nen made.” Fukushima Daigaku Gyōsei Shakai Ronshū, vol. 11, no. 4, 1998.

Nantucket Historical Association MS22. Log 347, Susan C. Austin Veeder Whaling Journal, 1848‒1853, https://archive.org/details/ms220log347 (accessed 9 December 2023).

New Bedford Whaling Museum. A Spectacle in Motion: The Grand Panorama of a Whaling Voyage ‘Round the World, volumes 1 and 2. New Bedford Mass., New Bedford Whaling Museum, 2018.

Newton, John. Savage History: A History of Whaling in the Southern and Pacific Oceans. Sydney, NewSouth, 2013.

Nicholls, Max. A History of Lord Howe Island. Hobart, Mercury Press, 1952.

Nōrinshō Suisankyoku. Hogeigyō. Tokyo, Nōgyō to Suisansha, 1938.

Reid, Anthony. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce Vo. 1: The lands Below the Winds. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1988.

Richards, Rhys. “Honolulu and Whaling on the Japan Grounds.” The American Neptune: Maritime History and Arts, vol. 59, no. 3, 1999: pp. 189‒197.

Rykhteu, Yuri. When the Whales Leave (trans. Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse). Minneapolis MN, Seedbank, 2020.

Sakakibara, Chie. “Whale Tales: People of the Whales and Climate Change in the Azores.” FOCUS on Geography, Fall 2011, pp. 75‒90.

Shoemaker, Nancy. Native American Whalemen and the World: Indigenous Encounters and the Contingency of Race. University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Sissons, David. “The Lady Rowena and the Eamont: The 19th Century” in Arthur Stockwin and Keiko Tamura eds., Bridging Australia and Japan: Vol. 1, The Writings of David Sissons, Historian and Political Scientist. Canberra, ANU Press, 2016, pp. 88‒89.

Smith, Howard M. “The Introduction of Venereal Disease to Tahiti: A Re-Examination.” The Journal of Pacific History, vol. 10, no. 1, 1975, pp. 38‒45.

Smith, Tim D., Randall R. Reeves, Elizabeth A. Josephson and Judith N. Lund. “Spatial and Seasonal Distribution of American Whaling and Whales in the Age of Sail.” PLOS ONE, vol. 7, no. 4, 2012, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0034905 (accessed 31 October 2023).

Stevens, Kate and Angela Wanhalla. “Māori Women and Shore Whaling in Southern New Zealand” in Ryan Tucker Jones and Angela Wanhalla eds., Across Species and Cultures: Whales, Humans and Pacific Worlds. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 2022.

Sydney Morning Herald. 19 July 1832.

Tonnessen, Johan Nicolay and Arne Odd Johnsen (trans. R. I. Christophersen). The History of Modern Whaling. London, C. Hurst and Co. 1982.

Tranquada, Jim and John King. The ‘Ukulele: A History. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press. 2012.

van Schendel, Willem. “Geographies of Knowing, Geographies of Ignorance: Jumping Scale in Southeast Asia.” Geography and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 20, no. 6, 2002, pp. 647‒668.

Watanabe Hiroyuki.Hogei Mondai no Rekishi Shakaigaku: Kin-Gendai Nihon ni okeru Kujira to Ningen, Tokyo, Tōshindō, 2006.

Wesley-Smith, Terence and John Goss eds. Remaking Area Studies: Teaching and Learning Across the Pacific. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 2010.

Wilson, Noell H. “Western Whalers in 1860s Hakodate: How the Nantucket of the North Pacific Connected Restoration Era Japan to Global Flows.” In Robert Hellyer and Harald Fuess eds., The Meiji Restoration: Japan as a Global Nation. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2020, pp. 40‒61.

Winchester, Simon. Atlantic: A Vast Ocean of a Million Stories. London, Harper Collins, 2010.

Yamamoto, Takahiro. Demarcating Japan: Imperialism, Islanders and Mobility. Cambridge Mass, Harvard University Press, 2023.

Yashiro Yoshiharu. Nihon Hogei Bunkashi. Tokyo, Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha, 1983.

Zdor, Eduard. “Subsistence Whaling of the Chukotkan Indigenous Peoples.” Senri Ethnological Studies, vol. 104, pp. 75‒92.

Zgusta, Richard. The Peoples of Northeast Asia Through Time: Precolonial Ethnic and Cultural Processes Along the Coast Between Hokkaido and the Bering Strait. Leiden, Brill, 2015, pp. 265‒266.

Notes

- Tom King’s death is recorded in the three surviving logbooks kept on the whale ship Navy during this voyage: one (ending abruptly in August 1862) written by the ship’s master, Andrew S. Sarvent, the second (ending in August 1863) written by the ship’s mates, Nelson C. Haley and John D. Dimond, and the third (spanning the eight months of the voyage) written by John D. Dimond. See Logbook of the Navy (Ship) out of New Bedford, Mass., mastered by Andrew S. Sarvent, kept by Andrew S. Sarvent on voyage 10 Aug. 1859-18 Apr. 1864; New Bedford Whaling Museum logbook collection, available on the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/logbookofnavyshi00navy (accessed 30 October 2023 – hereafter “Navy Logbook Sarvent”), pp. 4 and Logbook of the Navy (Ship) out of New Bedford, Mass., mastered by Andrew S. Sarvent, kept by Nelson C. Haley and John D. Dimond on voyage 10 Aug. 1859-18 Apr. 1864, New Bedford Whaling Museum logbook collection, available on the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/logbookofnavyshi00unse (accessed 20 October 2023 – hereafter “Navy Logbook Haley Dimond”), p. 244. The second logbook refers to “Tom King” simply as “Thomas”; also Logbook of the Navy (Ship) out of New Bedford, Mass., mastered by Andrew S. Sarvent, kept by John D. Dimond, https://archive.org/details/odhs-536 (accessed 20 October 2023 – hereafter “Navy Logbook Dimond”).

- Navy Logbook Haley Dimond, p. 244.

- The crew list includes Faustina de la Concepcion and Mariana Delgrado, see Navy Logbook Sarvent pp. 4; this was not particularly unusual – the logbook of the whaler Alice Frazier, New Bedford, Daniel H. Taber master, 1851-1855, kept by Benjamin F. Pierce, for example, refers to recruiting a stewardess in Melbourne, part way through the ship’s whaling voyage – see Logbook of the Alice Frazier (Bark), of New Bedford, Mass., mastered by Daniel H. Taber, on voyage from 10 Sept. 1851-5 Sept. 1855, kept by Benjamin F. Pierce, New Bedford Whaling Museum logbook collection, available on the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/alicefrazierbark00alic (accessed 30 October 2023), p. 180.

- See the crew list provided in Navy Logbook Sarvent pp. 2-4. It should be noted that this crew list appears to be incomplete, as there are crew members – including one Nikunau islander who was lost overboard – who are not listed in the captains log: see Navy Logbook Haley Dimond, p. 176.

- Perry to Secretary for the Navy John P. Kennedy, 14 December 1852, quoted in Francis L. Hawks ed. Sidney Wallach, Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan under the Command of Commodore M. C. Perry, United States Navy, New York, Coward-McCann Inc., 1952, p. 9.

- See Ryan Tucker Jones, “Leviathan’s Families: The History of Humans and Whales in the Pacific,” in Ryan Tucker Jones, Matt K. Matsuda and Paul D’Arcy eds., The Cambridge History of the Pacific Ocean: Volume 1 – The Pacific Ocean to 1800, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2023, pp. 46‒90; Graham Huggan, Colonialism, Culture, Whales: The Cetacean Quartet, London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2018; Honoré Foster, The South Sea Whaler: An Annotated Bibliography of Published Historical, Literary and Art Material Relating to Whaling in the Pacific Ocean in the Nineteenth Century, Sharon, Mass., Kendall Whaling Museum and Fairhaven Mass., E. J. Lefkowicz, 1985, and Honoré Foster, More South Sea Whaling: A Supplement to the South Sea Whaler, Canberra, Australian National University, 1991.