Abstract: This paper investigates the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the process of regional welfare-making in the Aso region (Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan). It demonstrates how local stakeholders such as social welfare councils have been promoting the ideal of community-based regional welfare, while adapting to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. As the pandemic hindered social exchange and amplified longstanding processes of community decline, it further complicates the ongoing challenge of activating local communities to realize the vision of a healthy “aging in place” based on mutual support.

Keywords: community-based integrated care, rural Japan, social welfare, COVID-19, demographic change, social distancing

Introduction

We had the earthquakes and now we have Corona. Social ties are becoming thinner, salon [preventive care] activities are being shut down, people meet each other less frequently and they wear masks, right? You can’t read the expressions of the faces well. All of these things make the power of the region weaker and weaker.

This concern was shared with us in November 2022 by a representative of a social welfare council (shakai fukushi kyōgikai, or shakyō) in the Aso region in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. The topic of our conversation was the “Aso Yamabiko Network,” an initiative of Aso’s seven social welfare councils to keep the region “liveable” (anshin shiteru kuraseru) for the rapidly aging population based on mutual support and the activation of community ties—or what our respondent referred to as the “power of the region” (chiiki no chikara). The regional initiative stands in the context of national policies to promote community-based care as a means to reduce the pressure on Japan’s old age care system, and the broader challenge to “create spaces for meaning” for the growing number of older adults facing social isolation (Kavedžija 2019: 140).

Realizing the ideal of community-based care has often been identified as a difficult task for local actors (see e.g., Dahl 2018). This article asks how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the long-term process of promoting community-based care in Japan’s rapidly aging rural areas. More precisely, we analyze how local actors such as social welfare councils and volunteers have been “making” community-based regional welfare (chiiki fukushi-zukuri),1 how these ongoing local activities and networks have shaped the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and how, in turn, temporary disruptions such as the pandemic add to the long-term challenges to establish community-based care. The Aso Yamabiko Network is a particularly productive case in this regard. On the one hand, the Aso region faces “persistent disruptive stressors” in the form of aging and depopulation that are common in rural areas in Japan (Okada 2022). Moreover, the Aso Yamabiko Network is a fairly typical example for a longstanding initiative to establish community-based care. On the other hand, Aso is a particularly disaster-prone region that is frequently confronted with short-term disruptions—including the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquakes, which caused devastation that affects local livelihoods still today. Community-level social ties and norms have been important resources to overcome disasters in Aso (Polak-Rottmann 2024; Abe and Murakami 2020). In contrast, the most common response to the COVID-19 pandemic—social distancing—potentially threatens the maintenance of these ties, and thus offers a different perspective on their significance.

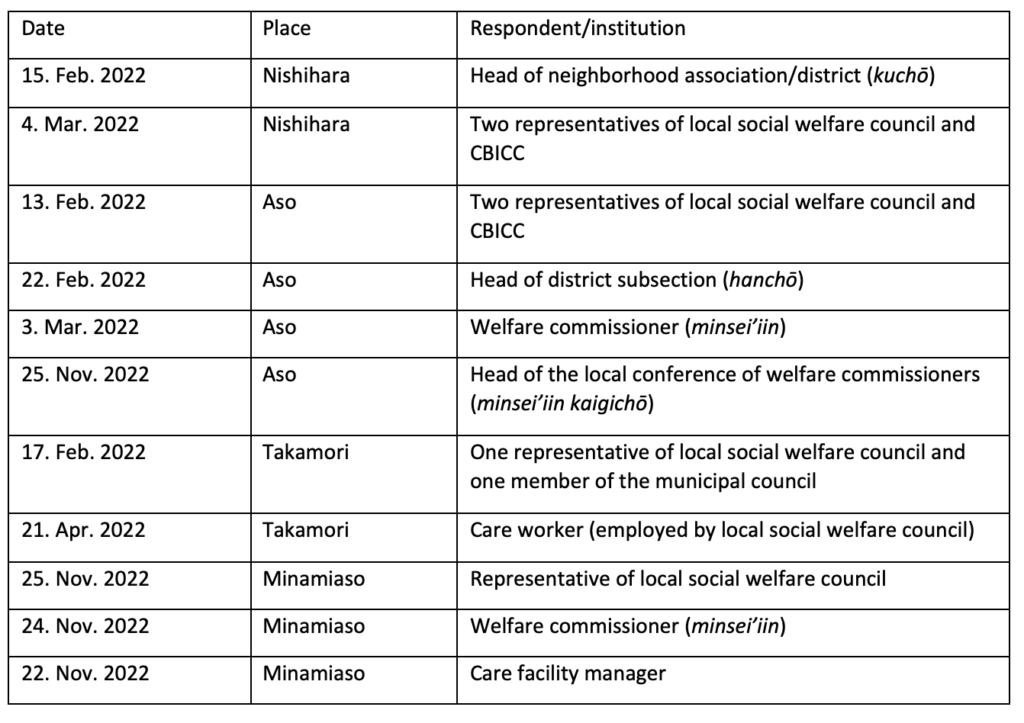

Based on long-term engagement with the Aso region and a series of semi-structured online interviews with various local stakeholders between February and November 2022, we demonstrate how established practices and dense network ties between volunteers, social welfare councils, and local communities have been an important resource to address the immediate challenges for social welfare provision during the height of the pandemic. The pandemic disruption further revealed the significance of the social dimension of preventive old age care, as welfare services and community life were reduced to their functional core. On the flipside, the pandemic amplified the long-term demographic challenges and the impact of previous disasters that have been undermining the “power of the region,” thus further complicating the task of establishing community-based care.

Before we address our findings in more detail, the following sections discuss the turn towards “community-based integrated care” in Japan, introduce the Aso Yamabiko Network initiative and the Aso region, and explain the roles and responsibilities of our respondents in the process of regional welfare-making.

Japan’s Turn Towards Community-Based Integrated Care

By 2025, Japan’s large baby boomer generation is projected to surpass the age of 75—the peak of a longstanding demographic development that has put massive pressure on Japan’s old age care system. Since the Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) was introduced in 2000, the growing number of care recipients has been steadily driving up the costs of the system, which is financed through contributions, co-payments, and local and national taxes. Severe labor shortages exacerbate the financial problems. By 2025, Japan is estimated to lack up to 320,000 care workers (Le Monde 2023). The mounting systemic problems of “rationalized bureaucratic and market mechanisms to deliver care” under the LTCI (Danely 2022: 133) increase the risk for older adults to suffer from social isolation or experience a lonely death, and add to the emotional and physical burdens for caring family members. Further, they pose questions on what makes life worth living in old age (Kavedžija 2019) and how to enable “successful” (Tanaka and Johnson 2021) or “active aging” (Prochaska-Meyer, Kieninger, and Nutz 2014).

The National Promotion of Community-Based Integrated Care

As a response to the multiple challenges surrounding the “2025 problem” (2025 nen mondai), local administrations and welfare providers as well as the central government have been turning to local communities to supplement formal care provision. Since a reform of the LTCI in 2005, the government promotes “community-based integrated care systems” (chiiki hōkatsu kea seido). The concept combines two elements: (1) integrating various public and private medical and care services and (2) activating local communities to create an inclusive local social environment which enables elderly people to “age in place,” ideally at home. The combination of both is meant to reduce the number of long-term care recipients, and thus the pressure on the LTCI system. The 2005 reform stipulated the creation of “community-based integrated care centers” (chiiki hōkatsu shien senta, CBICC), in which specialists such as care managers coordinate medical services as well as home, short-term, and long-term care services, and organize preventive care measures such as gymnastics or memory training. The Abe administration (2nd and 3rd cabinet; 2012–2020) set the target to establish local integrated community-based care systems nationwide by 2025, and increased the emphasis on preventive care and community-based daily life support. The latter includes activities such as volunteer-based shopping or cleaning support, mobility services, or the now ubiquitous fureai iki’iki salons, i.e., social gathering spots for older adults at the neighborhood level to maintain social exchange and/or promote preventive health care (Dahl 2018; Costantini 2021).

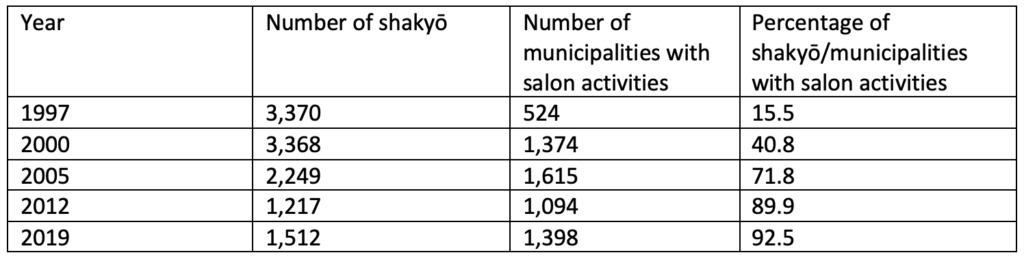

Noticeably, social welfare provision in Japan has been relying on state-society cooperation long before the concept of community-based integrated care was born. This is reflected in the roles of welfare commissioners and local social welfare councils. Welfare commissioners (minsei’iin) are paid volunteers, who are appointed by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW) to “monitor” the social welfare needs of a particular neighborhood or district. The roots of the minsei’iin system go back to the prewar period (Goodman 1998). As of 2020, there were 230,690 welfare commissioners in Japan (MHLW 2021). Minsei’iin typically cooperate closely with local social welfare councils (shakyō). Social welfare councils are quasi-public associations which are both closely tied to the state and embedded in local communities, and have been established in virtually all Japanese municipalities since the 1970s (Estévez-Abe 2003; Haddad 2011). They coordinate various private and public actors involved in social welfare provision at the municipal level, offer counseling and information, and provide welfare services themselves. Their income is derived from public sources, services offered under the LTCI scheme, and membership fees from local residents (Zenshakyō et al. 2020). The national federation of social welfare councils is committed to the promotion of “regional welfare” (chiiki fukushi), which is explicitly based on “cooperation between local residents, public, and private social workers […] to ensure that local residents can lead safe and peaceful lives” (Zenshakyō 2023). Given their longstanding role as linchpins between local administrations, communities, and welfare providers, it is no surprise that social welfare councils are involved in virtually all aspects of building community-based integrated care systems. Most shakyō (91%) coordinate volunteering activities, typically including the organization of fureai iki’iki salons. Many shakyō are also directly or indirectly involved in running local community-based integrated care centers (Zenshakyō et al. 2020).

Challenges and Contradictions

The growing emphasis on community-based integrated care has been discussed from various disciplinary perspectives, both in Japan and as a potential model for other countries with similar demographic challenges in Asia (Noda et al. 2021) or Europe (Waldenberger et al. 2022). Apart from an ongoing debate on the characteristics and the viability of the concept itself (Tsutsui 2014; Sudo et al. 2018; Costantini 2021; Niki 2019; Dahl 2018), a growing body of case studies focuses on the highly diverse local implementation process. Critics point to significant gaps between the ideal of community-based integrated care and its implementation on the ground—especially since the responsibility for the realization of the concept was further shifted onto local governments in 2014. Not all local governments and social welfare councils have the financial and human resources to shoulder these additional responsibilities, which potentially exacerbates intra- and interregional disparities in social welfare provision (e.g., Tokoro 2016; Inoue 2016; Numao 2016; Hatakeyama et al. 2018). The staff of community-based integrated care centers regularly report stress from heavy workloads and a lack of personal and financial capacities to perform their complex tasks (MUFG 2021: 308; see also Kanai and Kumazawa 2021; Tomita et al. 2015; Wake 2014). Limited financial and professional resources further increase the pressure to mobilize volunteers and other community actors, but the prospects to do so are limited. As Dahl notes, the government concept of community-based care appeals to “idealized images of Japanese community life.” Yet, these ideals may not exist in local practice. Instead, Dahl found local actors in charge of activating the community to perceive their task as frustrating and inefficient (Dahl 2018: 52–55).

A Rural Perspective on Community-Based Care

Noticeably, Dahl based his critique on field research in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Rural areas face different challenges, but also have different resources for realizing community-based preventive care (Heidt 2017). In large parts of rural Japan, the “2025 problem” is exacerbated by higher aging rates, ongoing outmigration of younger residents, underdeveloped care markets, weak fiscal resources, and the repercussions of decentralization and administrative restructuring in the mid-2000s (Manzenreiter, Lützeler, and Polak-Rottmann, 2020). However, numerous studies have pointed out that these widespread challenges should neither be mistaken as a one-way street into rural decline (Odagiri 2016; Tokuno 2015; Traphagan 2020), nor do they necessarily translate into purely negative outcomes for old age care: compared to metropolitan centers, forms of mutual support such as gift exchange or regular community work are still more common in rural areas (Tanaka and Johnson 2021). Similarly, established institutions for local self-governance such as neighborhood associations continue to have higher membership rates and tend to perform a broader range of functions than their urban counterparts (Tsujinaka, Pekkanen, and Yamamoto 2014; MIC 2021). Based on these social foundations, rural communities across Japan—often in cooperation with local governments and social welfare councils—have been able to extend and adjust existing social ties and practices to supplement gaps in formal welfare provision, from volunteer-based mobility services to meal deliveries, innovative day care concepts, or health monitoring (Gagné 2022; Odagiri 2011; Ikegami 2013; Okada 2022; Tanaka and Johnson 2021; Yamaura and Tsutsui 2022). Notably, these rural welfare initiatives have often preceded national policy initiatives (e.g., Gagné 2022). In fact, the concept of community-based integrated care itself goes back to rural models (Hatano et al. 2017; Costantini 2021). Focusing on rural areas thus offers the opportunity to capture not only the challenges, but also the potential of community-based care.

The Aso Yamabiko Network and the Aso Region

This article adds to the existing literature by investigating how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the long-term efforts of establishing community-based care in rapidly aging rural areas. Throughout the pandemic, the Japanese government refrained from ordering national lock-downs, and instead relied mostly on prefectural and local authorities to create and enforce countermeasures. Especially in the first phase of the pandemic, the number of deaths remained relatively low, which was not least linked to an efficient protection of long-term care facilities (Estévez-Abe and Ide 2021). Beyond posing an additional health risk especially for older residents, however, the pandemic also severely reduced the opportunities for social exchange due to a common application of social distancing rules, in Japan referred to as “3C” (san-mitsu): avoiding confined spaces, crowded settings, and close-contact situations. This raises the question how local actors such as social welfare councils have balanced the task of preventing infections and their long-term efforts to maintain and expand community-based care.

To pursue this question, we turn to the Aso region in Kumamoto Prefecture. In 1997, the Federation of Social Welfare Councils in the Aso Block (Aso Burokku Shakai Fukushi Kyōgikai Rengōkai, or Aso Shakyō Rengōkai) founded the Aso Yamabiko Network. The longstanding initiative promotes the ideal of a community-based care network, including not only welfare providers, but also residents and neighborhood groups, as well as postal workers, police, or fire brigades. These groups and individuals are expected to engage in a broad range of “supporting activities” (sasaeai katsudō) to sustain the livelihoods of the aging population by looking out for each other, reporting problems to welfare professionals, maintaining social ties within the neighborhood, or acting as volunteers. The underlying idea of combining “social support,” “public support,” “self-help,” and “mutual support” (Aso Shakyō Rengōkai 2023) mirrors both similar initiatives in other areas as well as the national promotion of community-based care (see e.g., Dahl 2018; Okada 2022; Yamaura and Tsutsui 2022). Thus, the Aso Yamabiko Network constitutes a good example of an initiative in which established actors such as social welfare councils aim to combine existing ideas and practices of “regional welfare” with more recent national policy objectives.

Both the activities and the challenges of the Aso Yamabiko Network are closely tied to the region it serves. Aso can be broadly conceived as a rural area, which has seen aging and outmigration at levels that are similar to other regions outside Japan’s metropolitan centers (Lützeler 2016). Socio-culturally, geographically, and socio-economically, the region is shaped by the active Aso volcano, which separates the Aso valley in the north (Aso-shi; see Fig. 1) from the Nangō valley in the south (Minamiaso-mura and Takamori-machi). The characteristic grassland (sōgen; see Fig. 2) on the slopes of the caldera is maintained through community practices such as annual burning (noyaki) (see e.g., Wilhelm 2020). These unique geographical features contribute to Aso’s popularity as one of the most visited touristic spots in Kumamoto Prefecture (Kumamoto-ken Kankō Senryaku-bu Kankō Kikaku-ka 2022). Yet, they also render the region vulnerable to disasters such as floods and earthquakes. The most devastating disaster in recent years, the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquakes, destroyed both residential homes and the public infrastructure in the region. The frequent exposure to disasters adds another facet to the case. Several studies have highlighted the significance of local community ties as a crucial resource in mitigating the impact of the Kumamoto Earthquakes (Abe and Murakami 2020; Polak-Rottmann 2024), and strengthening the region’s disaster response is also among the core objectives of the Aso Yamabiko Network. As we will show in more detail below, the experiences with such disruptions are reflected in the impact and the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is important to mention that the Aso region is by no means a homogenous space. The organization behind the Aso Yamabiko Network—the Aso Shakyō Rengōkai—consists of no less than seven local social welfare councils, each of which represent one local administrative unit: Aso-shi, the region’s central and most populous municipality, and then six smaller towns and villages that belong to the Aso District (Aso-gun, see Tab. 1). Together, these municipalities have less than 60,000 inhabitants, but cover an area twice as large as Tokyo’s 23 special wards. The municipalities within the region also differ markedly with respect to their size, character, and socio-economic situation.2 While Aso-shi consists of depopulating rural areas as well as densely populated settlements with numerous small shops and restaurants, Minamiaso-mura, Takamori-machi and especially Ubuyama-mura are much smaller in scale, predominantly rural, and less developed in terms of infrastructure (see Table 1). Accordingly, the Aso Yamabiko Network rests on top of a highly diverse web of welfare-related actors, groups, and initiatives at the municipal and sub-municipal level.

Methodology

Inextricably linked to our research interest on the impact of “social distancing,” the COVID-19 pandemic severely restricted our own access to the people whose situation we wanted to learn more about. The Japanese government closed the borders for non-Japanese citizens between March 2020 and October 2022. Consequently, we conducted semi-structured online interviews with representatives of social welfare councils, welfare commissioners (minsei’iin), the leaders of local neighborhood associations and their sub-sections,3 as well as the manager of a private welfare corporation, first in the context of a 16-day student research project in February 2022 (Jentzsch and Polak-Rottmann 2023; see Fig. 3), then in a series of follow-ups and additional interviews between March and November 2022 (see appendix). This research strategy offered a unique perspective on the efforts of those local actors struggling to maintain and expand social ties within and between aging communities in the region. In addition to the interviews, we collected municipal social welfare plans as well as materials issued by the Aso Shakyō Rengōkai and the respective local social welfare councils. To capture the considerable intraregional heterogeneity, we covered four different municipalities: Minamiaso-mura and Aso-shi, both of which are the result of administrative restructuring in the mid-2000s, the demographically stable Nishihara-mura, and Takamori-machi, which has the highest aging rate in the region. Using MAXQDA, we analyzed the data in a first round of initial coding based on Charmaz (2014), and then sorted our 714 codes in broader analytical categories. Noticeably, we conducted our study based on previous long-term fieldwork in the Aso region since 2018 (Askitis et al. 2020; Polak-Rottmann 2023; Polak-Rottmann 2024). This longstanding engagement with the region significantly improved our access to the field, and allowed us to analyze our findings on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the context of long-term challenges and previous disasters.

Regional Welfare-making in Aso

To understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on regional welfare-making in Aso, our analysis first focuses on the character and objectives of the Aso Yamabiko Network initiative, and discusses the crucial roles of established “linking agents” at the municipal and sub-municipal level—local social welfare councils, minsei’iin, and community leaders. We also highlight some of the ongoing efforts to extend, supplement, and professionalize existing community ties and functions against the background of aging and outmigration, which is the core objective of the Aso Yamabiko Network initiative. Against this background, we analyze how the actors within the Aso Yamabiko Network responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings show how the pandemic disruption revealed the strengths, but also amplified the long-term challenges, of community-based welfare provision in the Aso region.

The Aso Yamabiko Network and the Promotion of a “Moral Economy of Care”

The Aso Yamabiko Network initiative has both a normative and a practical dimension. At the regional level, the normative dimension dominates. The regional federation of social welfare councils (Aso Shakyō Rengōkai) promotes the Aso Yamabiko Network through leaflets and pamphlets (see Fig. 4) as well as on its homepage. These publications transport the ideal of community-based regional welfare that rests on mutual support as a mainstay of Aso’s unique regional “character.” This ideal is not least reflected in the name itself: “Yamabiko” refers to a mountain spirit (yōkai), but also means “echo.” Accordingly, the Yamabiko Network symbolizes the voices of the Aso people asking each other if everything is OK—a choir of neighborly care echoing back from the steep slopes of the Aso caldera. Importantly, community-based care is not promoted as a new approach, but rather as an expression of longstanding norms and practices characteristic for the region. An older version of the network’s pamphlet states:

In Aso, spontaneous forms of mutual support such as neighborhood associations, cooperative social bonds (yui) or kachari (regional dialect for mutual support) have existed long before the term “volunteer” was born.

A representative of the social welfare council in Minamiaso-mura describes the rationale of the Aso Yamabiko Network in a similar way:

Aso is one big family, and if there is any problem, we can reach out to each other. For example, when somebody made a delicious dumpling soup, they bring it to their neighbors. Or: “Yesterday there was no light on at my neighbor’s place, but they were not at our gathering either.” We look after each other and the Aso Yamabiko Network is an organization that makes use of this very process of organizing mutual care. (Interview with Social Welfare Council in Minamiaso-mura, November 25, 2022)

While these quotes are certainly painting an idealized picture of rural community life, they also point to the core objective of the Aso Yamabiko Network: the initiative aims to “make use” of already existing local norms and practices as the foundation to realize a more extensive form of community-based care. This mission resonates with Gagné’s arguments on the “local moral economy of care” in an aging village in Nagano prefecture. There, historically grown “long-term relationships, existing local associations, and resilient social values” served as the foundation for innovative local approaches to day care and social inclusion of the village’s rapidly aging population (Gagné 2022: 112). Noticeably, however, the Aso Shakyō Rengōkai itself is an umbrella organization with very limited capacities for independent (local) action. Its main functions are restricted to gathering and disseminating information at the regional level, including a disaster response manual, a region-wide emergency call list, or manuals on other health-related topics. The concrete, everyday process of building the Aso Yamabiko Network—rather, the efforts to translate the normative ideal of community-based care into local practice—take place at the municipal and sub-municipal level.

Connecting Communities and Integrating Stakeholders: Shakyō, Minsei’iin and Local Leaders

The foundation of the Yamabiko Network is a set of established local actors that we conceptualize as “linking agents”: local social welfare councils, welfare commissioners (minsei’iin), and the leaders of local neighborhood associations. Together, these linking agents routinely maintain connections to local stakeholders, and information flows between local communities, local administrations, and welfare providers.

Operating at the municipal level, local social welfare councils obtain a central position in the Aso Yamabiko Network—they are “the group that promotes regional welfare” (chiiki fukushi o suishin suru dantai, interview with Social Welfare Council in Minamiaso-mura, November 25, 2022). Local social welfare councils coordinate volunteer activities, either in cooperation with the local administration or—such as in Minamiaso—with private welfare providers. Moreover, all seven social welfare councils in the Aso region operate community-based integrated care centers. As such, they constitute the linchpin between established local groups and actors, volunteers, and welfare providers and more recently created formal institutions of community-based integrated care. A representative of the social welfare council in Minamiaso described this role as follows:

We are the entrance (iriguchi) and then we give advice or connect people to the community-based integrated care center. They will visit a household and collect data of clients and look at their current situation at home. Then we connect them to the local administration or a hospital. You see, it is not only paperwork, but we will go into our community, take part in (fureai iki’iki) salons, and help during difficult times. (Interview with Social Welfare Council in Minamiaso-mura, November 25, 2022)

Importantly, however, local social welfare councils themselves lack the organizational capacities to maintain close ties with every community. Aso-shi alone, for example, consists of 87 districts (chiku), some of which are further divided into sub-districts (han). Thus, social welfare councils rely on welfare commissioners (minsei’iin), who serve as direct “pipeline” to the community level. Typically, a welfare commissioner serves only one district—their own—although there are exceptions. The main responsibility of minsei’iin is “watching and protecting” (mimamori): gathering information on older adults and other residents in need of social support and passing this information on to the social welfare council or other authorities. Depending on the situation and the minsei’iin, mimamori can also entail more open forms of social care, such as chatting with older adults living alone, or helping them with everyday problems (see also Danely 2019).

Minsei’iin typically work closely with the leaders of neighborhood associations, who are responsible for organizing local community life and exchanging information between the local government and their respective districts. Some of the tasks of these local leaders are directly related to social welfare, such as organizing fureai iki’iki salons and disaster trainings, or collecting social welfare council fees. In a more general sense, neighborhood associations and related groups form the basis for a broad range of longstanding ties and practices, from regular meetings, maintaining communal grassland, to cleaning roads or organizing festivals. Our respondents frequently emphasized these ties and practices as the social foundation of community-based welfare, thereby using normatively charged phrases such as the “resources of being connected” (tsunagatte iru to iu zaisan, interview with local leader in Nishihara-mura, February 15, 2022) or the “power of the region” (chiiki no chikara). The minsei’iin system also rests on this foundation. Officially, minsei’iin derive their legitimacy from being formally recognized by the MHLW. In practice, however, their role crucially hinges on being recognized as “trustworthy persons” by their community (tayoreru sonzai), which provides the legitimacy to perform their tasks. Two minsei’iin described their role as a duty towards the districts they were born and raised in.

I’ve been living here for 70 years. I am doing well, and my family is very supportive. We are a family of eight: my wife, my daughter and her husband, and four grandchildren. Everyone is in good health, and when I say, “Let’s do something,” they support me. I took on the position as minsei’iin as I want to help the local people. (Interview with minsei’iin in Minamiaso-mura, November 24, 2022)

After I retired from my job at the local administration, I thought I’d focus on work around the house. But at the time, our minsei’iin stepped down, so the [responsibility] came my way (laughs). (Interview with the head of the minsei’iin association in Aso-shi, November 25, 2022)

In both cases, the respondents were asked to become minsei’iin by the local leader. In turn, the minsei’iin expressed a deep sense of responsibility towards their community. One respondent explained that he regularly reports his activities to the community to justify that he receives a small compensation, and feels obliged to take part in district-level social events, such as gate-ball4 or local festivals.

Noticeably, the roles, self-images, and orientations of these linking agents differ. Minsei’iin and local leaders are primarily oriented towards the well-being of their community, and not towards the adjacent districts, the municipality, or the Aso region. In contrast, social welfare councils are oriented towards the broader process of regional welfare-making. They bundle the vertical information flows from each community to make sure that socially vulnerable residents are being “monitored” on a regular basis (interview with representatives of social welfare council and CBICC in Nishihara-mura, March 4, 2022; see also Tab. 4). Working in the other direction, they disseminate information back to the community level by issuing reports or posters, providing vulnerable households with emergency contacts, and holding informational events and festivals. This has a normative dimension as well, in that local social welfare councils promote the ideal of mutual support and community-based care within their jurisdictions, and—via the Aso Shakyō Rengōkai—on the regional level.

Long-term Challenges: Activating and Supplementing Eroding Community Functions

Despite this dense web of institutionalized ties between communities, social welfare councils, and other stakeholders, the Aso Yamabiko Network is far from being “complete.” The head of a private care facility in the region criticized that cooperation between the various local stakeholders was still underdeveloped, which limits what she referred to as the “welfare power” (fukushi ryoku) in the region (Interview with manager of a care facility in Minamiaso-mura, November 22, 2022). Moreover, while our respondents emphasized the significance of existing community ties and practices as the social foundation of regional welfare, they consistently perceived this foundation to be in steady decline: threatened by aging and out-migration, or, in more urban areas, a growing share of nuclear families and singles who are less invested in maintaining neighborhood-level ties and underlying social practices. In many parts of Aso, once ubiquitous local groups (e.g., housewife associations) have already disappeared, and neighborhood associations increasingly struggle to sustain communal practices, including the grassland maintenance (Wilhelm 2020). More generally, while a decrease in three-generational households and a growing number of older adults living alone increases the demand for community-based care, the capacities of established local social structures to answer these challenges are seen as insufficient. These concerns—shared by our respondents and evident in aging rates of up to 43% and long-term depopulation rates of up to 18% (see table 1)—inform the core objective of the Aso Yamabiko Network: existing elements of community-based care must be extended, revived, or, if necessary, supplemented, and new (or more) community members must be activated. On the municipal and sub-municipal level, there are various concrete efforts to realize this normative ideal. We focus briefly on two main initiatives: mobilizing volunteers and strengthening preventive care through the promotion of “salon” activities.

Recruiting New Members for the Aso Yamabiko Network

One tangible effect of demographic decline is that it overstretches the capacities of minsei’iin. In the rural outskirts of Aso-shi, welfare commissioners already must serve more than one neighborhood, which increases costs and efforts, and can thin out the social ties between communities and minsei’iin. More generally, one respondent felt that the minsei’iin—themselves retirees—increasingly require more support from other community members to fulfill their responsibilities (interview with the head of the minsei’iin association, Aso-shi, November 25, 2022). Against this background, local social welfare councils in the Aso Yamabiko Network actively try to recruit volunteers to strengthen local mimamori systems. One of these initiatives in Nishihara explicitly appeals to the need to increase the “power of the region” (chiiki no chikara)—a reference to the (eroding) social foundation of community-based care. Volunteers are also mobilized for other tasks. Another initiative in Nishihara called the Livelihood Support Project matches volunteers with older adults in need of help with everyday challenges, such as shopping or simple home repairs. The system entails a small compensation. For example, for a five-minute task a volunteer receives 150 Yen, of which the recipient pays 100 Yen, and the social welfare council takes over the remaining 50 Yen. If recipients cancel an appointment without further notice, they must pay a 200 Yen cancellation fee.

While the efforts to supplement the mimamori system aim to strengthen an existing network of “social monitoring” with new members, the latter initiative reflects the objective to extend and formalize previously informal forms of mutual neighborhood support, which are undermined by a growing number of older adults living alone. Both constitute examples for how local social welfare councils combine normative appeals to established forms of support with concrete incentives and procedures to mobilize individual community members.

Promoting and Professionalizing Fureai Iki’iki Salons

The promotion of fureai iki’iki salons provides a particularly salient example for these ongoing efforts. Fureai iki’iki salons (“lively meeting salons”) are regular events typically held at the neighborhood level, in which older adults—especially those living alone—get together for social exchange, cultural activities, or preventive health care. Fureai iki’iki salons have gained significance all over Japan since the introduction of community-based integrated care (see Table 2). They are typically supported by local social welfare councils financially and organizationally.

In the Aso region, the promotion of salon activities constitutes a core element of regional welfare-making. Our respondents consistently referred to fureai iki’iki salons as crucial instruments for preventing older adults from becoming isolated, helping them maintain mental and physical abilities, and delaying their hospitalization or entry into long-term institutional care. Local social welfare councils in the Aso Yamabiko Network are eager to promote salon activities in multiple ways, from advertising model cases to concrete support such as financial support, picking up participants at home, and mobilizing and coordinating volunteers. Importantly, however, these salons are ultimately a community-based form of welfare provision, which neither shakyō nor local governments can simply install: if and where salons are held depends on cooperation and consensus in the respective community, and on local leaders issuing a formal application for support from the respective social welfare council.5 When one rural district in Minamiaso-mura was urged to establish a fureai iki’iki salon, the current minsei’iin and his predecessor discussed the issue with the residents and arrived at the conclusion that the district, particularly its farming population, was still “too busy” to organize salon activities.

Everyone in this area is quite busy, even the elderly. When I approached the elderly people about the possibility of getting together two or three times a week for tea drinking, they said, “That would be difficult,” so they couldn’t do it. So, I could not proceed with the discussion. (Interview with minsei’iin in Minamiaso-mura, November 24, 2022)

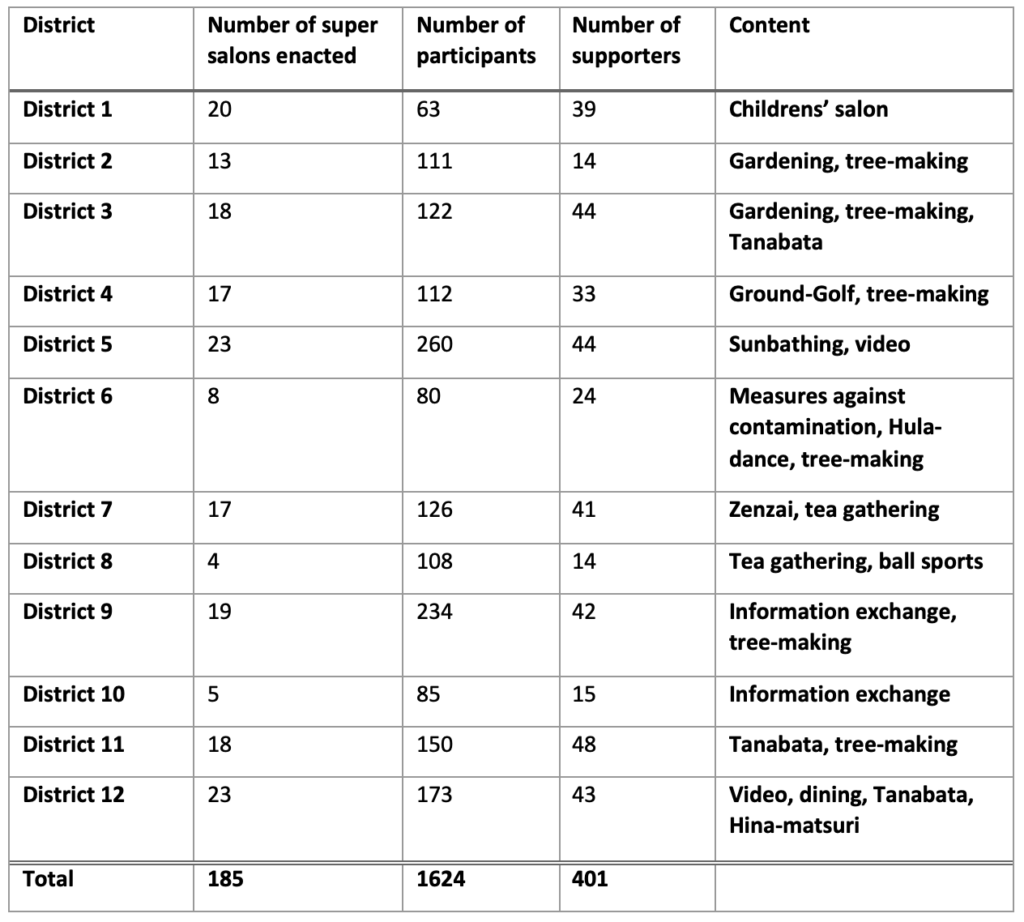

Given the dependence on community-level cooperation, access to preventive community-based care is thus necessarily patchy, and can differ even between neighboring districts. Moreover, respondents consistently reported that existing community-level fureai iki’iki salons were neither frequent enough nor capable of addressing the increasing demand for preventive health care, specifically regarding physical mobility and dementia. Thus, there are various initiatives within the Aso Yamabiko Network to expand and professionalize existing salon activities. In Takamori-machi, a health care worker employed by the social welfare council took on the task to integrate memory training, gymnastics, or nutritional advice into the program of fureai iki’iki salons. He also aims to expand the availability of “mini day services,” small-scale day care programs for older adults, with the help of both volunteers and professionals. In Nishihara-mura, the social welfare council leads a comprehensive municipal effort to establish so called “super salons,” Super salons are meant to supplement “normal” community-based salons (typically held monthly or even rarer) with bi-weekly (ideally weekly) events and a more extensive program. According to the social worker in charge of the project, this improves both the social and health-related functions of the salons:

If you hold the salon only once per month, you will meet that one person really just once. If you make it once every week, it is much easier to assess each participant’s situation, and everybody gets closer. I think it’s more fun for them and I think that it’s quite successful. (Interview with representatives of social welfare council and CBICC in Nishihara-mura, 4. March 4, 2022)

Compared to regular fureai iki’iki salons, super salons show a higher degree of professionalization, with social workers and caregivers involved in the planning of the events. They offer a variety of activities, such as gardening, golf, tea drinking, or health-related advice. The super salons are supported by a strikingly large number of volunteers, who receive training and a small compensation for their task.

Nishihara’s super salon initiative stands out as a particularly ambitious and resource-intensive example for the ongoing efforts to professionalize preventive community-based care. As such, the initiative also points to how regional welfare-making is shaped by uneven resource endowments. Situated close to the prefectural capital Kumamoto-shi and the regional airport, Nishihara-mura has not only a more stable population and a much lower aging rate than the other municipalities in Aso, but also a stronger fiscal base (see Table 1). This relatively fortunate socio-economic situation seems to facilitate the promotion of more professional and formalized forms of community-based care, even if the demand may be higher in the other municipalities in the region. Despite these advantages, however, the expansion of super salons has stagnated since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is just one example for the various ways in which the pandemic affected regional welfare-making in Aso. The following sections discuss the impact of the pandemic in more detail.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Process of Regional Welfare-making

As mentioned above, the Japanese government refrained from issuing nation-wide lockdowns to reduce the infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, the measures to contain the virus in the Aso region were a dynamic mix of prefectural guidelines, rules issued by local governments, and corresponding recommendations and measures formulated and enacted by social welfare councils, welfare corporations, or local communities themselves, with slight differences not only between municipalities, but also between districts within the same municipality. As everywhere in Japan, strict and efficient measures were taken to protect the residents of long-term care facilities (Estévez-Abe and Ide 2021; interview with manager of a care facility in Minamiaso-mura, November 22, 2022).

Outside hospitals and care homes, the most common countermeasure was social distancing. Over several years, most social events in the region were suspended and restricted, including community-based events and preventive care such as salon activities. While these measures certainly helped to keep the number of infections relatively low,6 they had a direct impact on the efforts to strengthen community-based care for those elderly residents not yet in long-term care. Our analysis focuses on three major themes in this regard: first, limited opportunities for social exchange posed concrete short-term risks, especially for elderly residents living alone. Second, the dense web of links to each and every community helped social welfare councils to keep track of the health situation of vulnerable residents. Similar to previous disasters, community ties thus proved to be an important and strikingly adaptive resource to reduce the risks associated with the pandemic. Third, however, the pandemic disruption amplified long-term concerns about a further erosion of the “power of the region,” or in other words, the social foundation of community-based care in the region.

Limiting Social Exchange

While social distancing affected all kinds of welfare-related events, a major concern shared by our respondents was the suspension or restriction of salon activities. The restrictions imposed on these events, in turn, highlighted their importance and, more precisely, the significance of their social dimension. Without salon activities, many older adults in the region lost not only the opportunity for occasional exercise, but also a chance to get out of the house, meet others, and have fun together. Several respondents observed that the decline in activities during the pandemic had concrete negative effects on both the physical and mental well-being of older adults in the region.

A lot of the elderly that visited the few mini day services that we’ve had during the pandemic told me that they were forgetting things more often and that their physical strength deteriorated. I wrote them down how to do some exercises and those who did them, could sustain their health. But many of those whose situation worsened moved to their children. (Interview with care worker in Takamori-machi, April 21, 2022)

They don’t go anywhere and feel lonely. So, when they don’t connect to other people, their muscles also get weaker. Once their strength decreases, their cognitive abilities also start to deteriorate. In addition to that, they stop caring for their appearance. Normally, they would think something like, “Today, there’s a salon and I meet some friends there, so what shall I wear today? How should I arrange my hair?” (Interview with Social Welfare Council in Minamiaso-mura, November 25, 2022)

Amplifying these combined physical and mental effects, other community-level activities—such as drinking parties, festivals, or sports events—were also cancelled, which further reduced the opportunities for social exchange beyond the household. Moreover, the suspension of fureai iki’iki salons and similar social events also meant that social workers had fewer opportunities to check on older adults’ health and mental situation. Social exchange was also limited on the municipal level, where the vertical links provided by minsei’iin and volunteers are shared and multiplied. For example, the minsei’iin conference in Aso-shi mostly avoided in-person meetings. This restricted the core function of the conference, which is to exchange information and practical advice among welfare commissioners. Additionally, as the head of the conference explained, it also affected the morale of newly recruited minsei’iin (Interview with the head of the minsei’iin conference in Aso-shi, November 25, 2022).

Given these restrictions on social exchange, the established vertical channels for social monitoring (mimamori) proved to be a vital resource. Deeply embedded in their respective communities, welfare commissioners reported little or no changes to their tasks and responsibilities during the pandemic. Potential problems, such as residents refusing to get in contact with welfare commissioners or social workers due to fear of infection, were reportedly rare on the community level (Interview with minsei’iin in Minamiaso-mura, November 24, 2022)—arguably a side effect of the local social embedding of the minsei’iin. Beyond the regular mimamori activities described above, some minsei’iin, social welfare councils and CBICCs also relied on “remote” mimamori via telephone. While ongoing or adapted mimamori activities may not have been sufficient to prevent loneliness or social isolation, the vertical flow of information between communities and the municipal level could thus be maintained. Table 4 illustrates the remarkable frequency of mimamori activities in Nishihara-mura’s districts from April 2018 to March 2022 in numerical terms. Although the total number of visits of the target population decreased from 2019 to 2020 by about 1,500 visits, it bounced back to 16,622 in 2021, demonstrating the ongoing efforts of local stakeholders to maintain the existing mimamori network. In this sense, the foundations of the Yamabiko Network have contributed to reducing some of the risks associated with social distancing, especially for the growing number of older adults living alone.

Doing What is “Necessary”

Reflecting the significance our respondents ascribed to the social dimension of preventive care, community-level traditional practices as well as health-related activities were not simply suspended, but also creatively altered to adjust to the “new normal.” Our respondents often emphasized their efforts to “come up with something” (kufū) and to “keep doing what is possible” (yareru koto o yarinagara) to maintain safe and healthy “aging in place” during the pandemic. Specific efforts were made to maintain salon activities whenever and wherever possible—not least because older adults would urge them to do so (interview with representatives of social welfare council and CBICC in Nishihara-mura, March 4, 2022). One way to “keep doing what [was] possible” was to work around the official guidelines for social distancing at the community level. As mentioned above, salon activities ultimately rested on community-level consensus. Thus, especially in more rural areas, some districts would decide to continue their activities despite rising numbers of infections in other areas. One social worker in Takamori-machi explained:

You see, in the mountains, we can continue with the salon activities, even if Corona spreads in the downtown area. […] Then there are also orders from the prefecture, the town or the administration that we will act upon. Further, we decided to organize the salons completely by ourselves as a social welfare council. We were concerned for our volunteers, so we let them choose freely whether they wanted to help us or not. And of course, the clients are free to come or stay at home, but they all came to our salon. (Interview with care worker in Takamori-machi, April 21, 2022)

In this sense, the significant degree of community-level autonomy provided the flexibility to adjust official guidelines to different situations at the sub-municipal level. Another strategy to “keep doing what [was] possible” was to adapt salon activities to social distancing rules, for example by focusing on the physical or mental training while restricting social aspects, such as tea breaks or the integration of seasonal festivals. Again, these efforts highlighted the significance of the social function of fureai iki’iki salons. Preventive community-based care does not have the same appeal for older adults once it is reduced to physical or mental exercise:

During Corona, we organized a sports class without talking for elderly, but I was told that it’s no fun. It’s a one-way street. Usually, it is my approach to mix the physical training with chatting and laughing with each other. Those who have been used to that found the new training rather dull. (Interview with care worker in Takamori-machi, April 21, 2022)

Beyond the realm of preventive care, local communities adjusted to the “new normal” in other ways, thereby further revealing the different dimensions of community functions. While the numerous local festivals and drinking parties that would normally follow meetings or communal work were cancelled, this did not mean that community life itself came to a halt. Instead, communities in the Aso region identified activities they deemed “necessary” and adapted or maintained these activities during the pandemic. This is similar to what Takeda (2022) observed in his study about how community practices and traditions have continuously been adapted throughout history to a variety of crises, with COVID-19 being one example. In the Aso region, “necessary” community functions mostly referred to joint cleaning of the roads and the seasonal burning of communal grassland (noyaki): “work to preserve the region” (chiiki o ijishite iku sagyō), as one of our respondents put it (Interview with social welfare commissioner in Aso-shi, March 3, 2022). The head of a district sub-section in Aso-shi explained the difference (Interview, February 22, 2022): “It is not that we do not meet because of Corona, but that it’s a good thing to meet when it’s necessary. […] We have to do the village activities to protect our area.”

This distinction between “necessary” and dispensable meetings reveals the multiple layers of community life and confirms the ability of local communities in the region to adapt in times of crisis—something that was also observed in the aftermath of the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquakes. In the case of the Kumamoto Earthquakes, however, the disaster created challenges that were visible, concrete, and urgent. In this situation, studies found that communities were able to utilize and, if necessary, reactivate dormant community functions to organize shelters, provide food and water, and provide comfort beyond the official disaster relief measures (Abe and Murakami 2020; Polak-Rottmann 2024). In the face of the invisible threat posed by the Coronavirus, however, communities’ adaptive abilities were focused on finding ways to uphold “necessary” maintenance and decision-making functions, while muting “soft” social aspects of community life to prevent the spread of the virus.

Short-term Adjustments and Long-term Concerns

Despite the differences between the two disasters, community functions and established ties between communities and municipal-level actors such as shakyō provided an important source for resilience during the pandemic. Both in the aftermath of the 2016 earthquakes and during the pandemic, the established patterns of information exchange between communities and local social welfare councils were crucial for monitoring health and safety of residents. And in both cases, community-level autonomy helped to adjust municipal measures to local demands; in the aftermath of the earthquakes, communities altered official evacuation plans according to their needs, while during the pandemic, remote districts worked around municipal guidelines to reinstate salon activities. A related effect of well-established ties between communities and administration should not go unmentioned: local authorities were also able to realize swift and comprehensive vaccination campaigns to protect the aging population when vaccines became available (interview with representatives of social welfare council and municipal council in Takamori-machi, February 17, 2022).

On the other hand, however, reducing community functions to what was “necessary” also came with some risks. Several respondents shared concerns that the effects of social distancing and the related decline of social aspects of community life could have lasting negative effects on already eroding community ties. Again, they related these concerns to the experiences following the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquakes. While community functions were an important source of resilience in the aftermath of the earthquakes, in the long run, the disaster accelerated demographic aging and community decline. The only university campus in the region was destroyed and not rebuilt, care facilities were damaged, and train services were disrupted until a partial reopening in 2020. As a result, many residents, including younger families, moved away, and the percentage of people aged 65 or older increased even quicker in the years after the earthquakes (Interview with care center in Minamiaso-mura, November 22, 2022, see also Table 1). In some places—most notably Nishihara-mura and Minamiaso-mura—destroyed areas were not fully rebuilt, and some villagers still lived in provisional housing when we conducted our study in 2022. A local leader explained the ongoing recovery efforts as a matter of rebuilding the community as a whole:

We talk about “recovering from the earthquakes” and I think that the basic infrastructure has been rebuilt. So, we have been able to provide the “hard” things, but I think that the community, the social relationships between people, have not yet recovered. I am afraid that this will have its effects on the big future. It’s really important to think whether the village can be sustained, if things stay that way. (Interview with local leader in Nishihara-mura, 15. February 2022)

His concerns directly relate to the broader objective of the Aso Yamabiko Network, and they illustrate how the pandemic hit the Aso region at the tail end of a difficult period of struggle and recovery, which took an especially heavy toll on the social side of community life. The effects of social distancing and focusing on the “necessary” aspects of community life amplified the “delayed recovery” of community ties from the 2016 earthquakes.7 Together, these short-term disruptions thus threaten to accelerate the long-term erosion of social foundations underlying community-based care networks in the region—a double blow for the “power of the region.” Again, it is important to note that the concern for the “power of the region” extends beyond the realm of welfare provision, and includes the maintenance of community activities such as festivals or local customs. Due to aging and outmigration, many of these activities had become increasingly difficult to sustain, even before the pandemic and the 2016 earthquakes. Although some respondents perceived the worst parts of the pandemic to be over since the vaccines became available, the concern remained that social events and traditions that were stopped for several years would be hard to revive.

We hope that we will once again be able to fully enjoy our festivals. However, things that have been running for ages have been stopped and I think that it will be hard to have them again. Unless there is someone who will take the lead and say, “Let’s do it!”, it will be difficult. It is easy to have people gather to have a party together, but for a festival you need a lot of preparation and so that’s why there needs to be someone who will manage the whole process. (Interview with minsei’iin in Minamiaso-mura, November 24, 2022)

Another respondent shared similar concerns:

In our district, the general assembly still relies on decision-making based on written documents and so on, we didn’t have a meeting for three years now. So yeah, there is some concern around here. But of course, to prevent the community from collapsing, local leaders try all kinds of things. (Interview with the head of the minsei’iin conference in Aso-shi, November 25, 2022)

Both quotes point to an important issue in the context of this article: whether community functions and social ties survive the pandemic is not just a matter of “natural” recovery, but also a question of active engagement, creative thinking (kufū), and leadership. This means, in turn, that bringing back community functions to “pre-pandemic levels” is another item on the list of long-term challenges faced by the Aso Yamabiko Network, which already has been struggling to revive, extend, and supplement existing community ties and functions since before the earthquakes and the pandemic struck. For minsei’iin as well as other members of the Yamabiko Network, the pandemic has thus increased the urgency of the mission to strengthen the “power of the region” by activating the community beyond its existing linking agents.

Conclusions

Against the background of ongoing public and academic debates about Japan’s aging population, demographic decline, and shrinking rural areas, this article investigated the case of the Aso Yamabiko Network and illuminated the concrete efforts of local stakeholders to activate the local community in preventing regional care systems from collapsing. Our study viewed these efforts through the lens of the specific challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. This perspective revealed both the strengths and the weaknesses of community-based regional welfare-making in Aso.

Contrary to what Dahl (2018) suggested, our data shows that community-based care is not just an empty signifier to legitimize changes to the LTCI scheme. In the Aso region, longstanding social ties, trust, and mutual support constitute both the normative underpinning and the concrete social foundation for preventive old age care, with tangible effects on the availability and the exchange of household-level information, as well as the availability of accessible opportunities for social exchange and preventive health care for older adults living alone, based on routine cooperation between communities, volunteers, and social welfare councils. In the face of severe demographic decline in some parts of the region, the activities under the Aso Yamabiko thus support, or at least prolong, residents’ safe and healthy “aging in place.” At the same time, however, “community” is also not a readily available resource for filling the gaps in formal care provision. Rather, community functions that were once taken for granted must be adjusted, (re)activated, or supplemented to address the mounting challenges that come with a growing number of older adults living (and possibly dying) alone, and the erosion of traditional forms of mutual support.

The pandemic highlighted the significance of these ongoing efforts in two ways. First, precisely because it restricted the social aspects of preventive old age care, the pandemic underlined the importance of mental well-being and social exchange for successful “aging in place.” Our respondents were acutely aware of the risks of long-term social isolation, which is reflected in their concern about the disruption of community activities such as festivals or assemblies, their efforts maintain and reinstate fureai iki‘iki salons wherever possible, as well as in the realization that focusing on physical exercise alone stripped the salon activities of their appeal. Second, established links within and between neighborhoods and with municipal-level actors, such as social welfare councils and the associated community-based integrated care centers, helped to alleviate some of the risks of social distancing. Community-level autonomy and mutual trust provided flexibility when adjusting social distancing rules to local needs and circumstances. Moreover, extensive mimamori activities continued to produce information on the situation of older adults even in the remote outskirts of the Aso region. The existence of such established links is certainly not unique to the Aso region (see e.g., Gagné 2022) and might add to the explanation for the somewhat surprising efficiency of Japan’s decentralized pandemic response (Estévez-Abe and Ide 2021).

Yet, the COVID-19 pandemic also shed light on the weaknesses of community-based welfare provision. Despite emphasizing the “power” of community ties, our respondents shared a sense of crisis regarding the future prospects of community-based care. Adding to the lingering effects of the 2016 earthquakes, the pandemic further undermined already fragile community ties and functions like festivals, drinking parties, fireworks, and so on, that form the social foundation of community-based care. Even in the absence of such disruptions, expanding the Aso Yamabiko Network has been an uphill battle that requires not only agency and leadership, but also human and financial resources, as evident in the initiatives in Nishihara. If the “power of the region” further erodes, the task to expand preventive old age care becomes not only more difficult, but potentially more expensive. Although our study was limited to the Aso region, with its specific strengths and vulnerabilities, the experiences discussed in Aso are indicative of how the pandemic has added to the “persistent disruptive stressors” in rural areas across Japan (Okada 2022). Our evidence thus suggests that the pandemic has further complicated the nation-wide implementation of community-based integrated care systems by 2025, in that it further increased the risks of social isolation and solitary deaths, and amplified problems such as the lack of human and financial resources at the local level to supplement eroding community functions for the provision of preventive old age care.

References

Abe, Miwa 安部美和 and Takeshi Murakami 村上長嗣. 2020. “農村集落におけるくらしの変化と熊本地震~南阿蘇村川後田区・加勢区の事例から [Changing life in rural communities and the Kumamoto Earthquakes: Examples from Kawagoda-ku and Kase-ku in Minamiaso-mura].” 熊本大学政策研究 [Kumamoto University Policy Research] 10: 29–39.

Askitis, Dionyssios, Antonia Miserka, and Sebastian Polak-Rottmann. 2021. “Exploring rural well-being through an interdisciplinary lens: The ‘Shrinking, but happy’ research team at the University of Vienna.” Asien: The German Journal on Contemporary Asia 158–159: 161–176. https://doi.org/10.11588/asien.2021.158/159.20427.

Aso Shakyō Rengōkai (Aso Burokku Shakai Fukushi Kyōgikai Rengōkai) “阿蘇ブロック社会福祉協議会連合会. 2023. 阿蘇やまびこネットワーク みんなでたすけあい・ささえあう地域づくり [The Aso Yamabiko Network: Making a Region, where Everybody Helps and Supports Each Other].” 阿蘇やまびこネットワークとは [What is the Yamabiko Network?], accessed 22 March 2023. https://www.asoyamabiko.jp/about/.

Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. London: SAGE.

Costantini, Hiroko. 2021. “Ageing in Place? The Community-Based Integrated Care System in Japan.” Gérontologie et société 43(165): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3917/gs1.165.0205.

Dahl, Nils. 2018. “Social Inclusion of Senior Citizens in Japan: An Investigation into the ‘Community-Based Integrated Care System.’” Contemporary Japan 30(1): 43–59.

Danely, Jason. 2019. “The Limits of Dwelling and the Unwitnessed Death.” Cultural Anthropology 34(2): 213–39.

Danely, Jason. 2022. Fragile Resonance. Caring for Older Family Members in Japan and England. Ithaca: Cornell University.

Estévez-Abe, Margarita and Hiroo Ide. 2021. “COVID-19 and Long-Term Care Policy for Older People in Japan.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 33(4–5): 444–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2021.1924342.

Estévez-Abe, Margarita. 2003. “State-Society Partnerships in the Japanese Welfare State.” In the State of Civil Society in Japan, edited by Frank J. Schwartz and Susan J. Pharr, 154–72. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gagné, Isaac. 2020. “Dislocation, Social Isolation, and the Politics of Recovery in Post-Disaster Japan.” Transcultural Psychiatry 57(5): 710–23.

Gagné, Isaac. 2022. “Mapping the Local Economy of Care: Social Welfare and Volunteerism in Local Communities.” In Rethinking Locality in Japan, edited by Sonja Ganseforth and Hanno Jentzsch, 102–16. London and New York: Routledge.

Goodman, Roger. 1998. “The ‘Japanese-Style Welfare State’ and the Delivery of Personal Social Services.” In the East Asian Welfare Model: Welfare Orientalism and the State, edited by Roger Goodman, Gordon White, and Huck-ju Kwon, 139–58. London, New York: Routledge.

Haddad, Mary Alice. 2011. “A State-in-Society Approach to the Nonprofit Sector: Welfare Services in Japan.” Voluntas, 22(1): 26–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-010-9135-7.

Hatakeyama, Teruo 畠山輝雄, Tsutomu Nakamura 中村努, and Hitoshi Miyazawa 宮澤仁. 2018. “地域包括ケアシステムの圏域構造とローカル・ガバナンス [Community-Based Integrated Care Systems in Japan: Focusing on Spatial Structures and Local Governance].” E-journal GEO 13(2): 486–510.

Hatano, Yu, Masatoshi Matsumoto, Mitsuaki Okita, Kazuo Inoue, and Keisuke Takeuchi. 2017. “The Vanguard of Community-Based Integrated Care in Japan: The Effect of a Rural Town on National Policy.” International Journal of Integrated Care 17(2): 1–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ijic.2451.

Heidt, Vitali. 2017. Two Worlds of Aging: Institutional Shifts, Social Risks, and the Livelihood of the Japanese Elderly. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Inoue, Nobuhiro 井上信宏. 2016. “高齢期の生活保障と地域包括ケア [Livelihood Security and Comprehensive Community Care in Old Age].” 社会政策 [Social Policy] 7: 27–40.

Jentzsch, Hanno and Sebastian Polak-Rottmann. 2023. “Rural spaces, remote methods – the virtual Aso Winter Field School 2022.” In Research into Japanese society, edited by Sebastian Polak-Rottmann and Antonia Miserka, 63–78. Vienna: Department of Japanese Studies, University of Vienna.

Kanai, Hideaki and Akinori Kumazawa. 2021. “An Information Sharing System for Multi-Professional Collaboration in the Community-based Integrated Health System.” International Journal of Informatics Information System and Computer Engineering 2(1): 1–14.

Kavedžija, Iza. 2019. Making Meaningful Lives: Tales from an Aging Japan. Ann Arbor: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kumamoto-ken Kankō Senryaku-bu Kankō Kikaku-ka 熊本県企画観光戦略部観光企画課. 2022. 令和4年(2022年)熊本県観光統計表 [2022 Tourism Statistics of Kumamoto Prefecture], accessed 12 February 2024. https://www.pref.kumamoto.jp/uploaded/life/190000_477617_misc.pdf.

Le Monde. 2023. “Inflation and staff shortages threaten Japan’s care for the elderly.” Le Monde, 13 July. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/economy/article/2023/07/13/inflation-and-staff-shortages-threaten-japan-s-care-for-the-elderly_6052027_19.html.

Lützeler, Ralph. 2016. “Aso: ein ländlicher Raum in der Abwärtsspirale? Bemerkungen zur Messbarkeit der Qualität regionaler Lebensbedingungen.” In Aso: Vergangenheit, Gegenwart und Zukunft eines Wiener Forschungsprojekts zum ländlichen Japan, edited by Ralph Lützeler and Wolfram Manzenreiter, 153–67. Vienna: Department of Japanese Studies, University of Vienna.

Manzenreiter, Wolfram, Ralph Lützeler, and Sebastian Polak-Rottmann (eds.). 2020. Japan’s New Ruralities: Coping with Decline in the Periphery. London: Routledge.

Matsumoto-shi Fukushi Seisaku-ka 松本市福祉政策課. 2021. “福祉づくりは地域づくり [Welfare-making is Region-making]” 福祉ひろばとは [What is the fukushi hiroba], accessed 27 February 2023. https://www.city.matsumoto.nagano.jp/uploaded/attachment/3818.pdf.

MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare). 2021. 令和2年度福祉行政報告例の概況 [Overview of Welfare Administration Reports in FY2020], accessed February 27 2023. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/gyousei/20/index.html.

MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare). 2023. 地域包括ケアシステム [The Community-Integrated Care System], accessed February 27 2023. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/hukushi_kaigo/kaigo_koureisha/chiiki-houkatsu/.

MIC (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications). 2021. 自治会・町内会の活動の持続可能性について [On the Sustainability of Neighborhood Associations’ activities.], accessed February 12 2024. https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000777270.pdf.

Miyake, Yasunari 三宅康成 and Takahiro Iseki 井関崇博. 2014. “農村地域における「ふれあいサロン」の実態と課題 -姫路市郊外のサロンを事例として [Actual Conditions and Subjects of Community Salon in Rural Area: A Case of Himeji Suburbs].” 兵庫県立大学環境人間学部研究報告 [Research Reports of the Faculty of Environmental and Human Studies at the University of Hyogo] 16: 99–109.

MUFG (Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group). 2021. 地域包括支援センターの効果的な運営に関する調査研究事業 [Report of the Survey and Research Project on the Effective Operation of Community Comprehensive Support Centers]. Tokyo: Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting.

Niki, Ryū 二木立. 2019. “日本の地域包括ケアの事実・論点と最新の政策動向 [Reality, Issues, and Recent Policy Trends in Japan’s Community-Based Integrated Care].” 日本福祉大学社会福祉論集 [Nihon Fukushi University Social Welfare Review] 140: 127–34.

Noda, Shinichiro, Paul M. Hernandez, Sudo, Kyoko, Kenzo Takahashi, Nam E. Woo, He Chen et al. 2021. “Service Delivery Reforms for Asian Ageing Societies: A Cross-Country Study Between Japan, South Korea, China, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines.” International Journal of Integrated Care 21(2): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5334/.

Numao, Namiko 沼尾波子. 2016. “社会保障制度改革と自治体行財政の課題 [The Reform of the Social Security System and Challenges for Local Administrative and Financial Governance].” 社会政策 [Social Policy] 7(3): 12–26.

Odagiri, Tokumi 小田切徳美 (ed.). 2011. 農山村再生の実践 [The Revitalization of Agricultural Mountain Villages in Practice]. 東京: 農山漁村文化協会 [Tokyo: Agricultural, Rural and Fishery Culture Association].

Odagiri, Tokumi 小田切徳美. 2016. 農山村は消滅しない [Mountain villages will not disappear]. 東京: 岩波書店 [Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten].

Okada, Norio. 2022. “Rethinking Japan’s Depopulation Problem: Reflecting on over 30 Years of Research with Chizu Town, Tottori Prefecture and the Potential of SMART Governance.” Contemporary Japan 34(2): 210–27.

Polak-Rottmann, Sebastian. 2023. “Being active and sharing happy moments: exploring the relationship of political participation and subjective well-being.” Asian Anthropology 22(4): 293–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/1683478X.2023.2215639.

Polak-Rottmann, Sebastian. 2024. Wie politische Partizipation Freude bereiten kann. Sechs Dimensionen des subjektiven Wohlbefindens politisch handelnder Personen im ländlichen Japan. Munich: Iudicium.

Prochaska-Meyer, Isabelle, Pia R. Kieninger, and Stefan Nutz. 2014. 65+ Being old in rural Japan, accessed February 8 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GDyPwiVObzg.

Sudo, Kyoko, Jun Kobayashi, Shinichiro Noda, Yoshiharu Fukuda, and Kenzo Takahashi. 2018. “Japan’s Healthcare Policy for the Elderly through the Concepts of Self-help (Ji-jo), Mutual Aid (Go-jo), Social Solidarity Care (Kyo-jo), and Governmental Care (Ko-jo).” Bio Science Trends 12(1): 7–11.

Takeda, Shunsuke. 2022. “Continuation of Festivals and Community Resilience during COVID-19: The Case of Nagahama Hikiyama Festival in Shiga Prefecture, Japan.” Japanese Journal of Sociology 31: 55–66. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ijjs.12132.

Tanaka, Kimiko and Nan E. Johnson. 2021. Successful Aging in a Rural Community in Japan. Durham: Caroina Academic Press.

Tōkai Daigaku 東海大学 2022. 熊本県の市区町村ごとの新型コロナウイルス新規感染者数 [Number of new cases of new coronavirus infection by municipality in Kumamoto Prefecture], accessed March 21 2024. http://covid-map.bmi-tokai.jp/choroplethmap_kumamoto/.

Tokoro, Michihiko 所道彦. 2016. “座長論文: 社会保障改革と地方自治体 : 論点の整理と今後の課題 [Keynote: Social Protection Reform and Local Governments – Summary of the Issues and Future Challenges].” 社会政策 [Social Policy] 7(3): 3–11.

Tokuno, Sadao 徳野貞雄. 2015. “人口減少時代の地域社会モデルの構築を目指して [Toward the development of a regional social model in an era of population decline].” In: 暮らしの視点からの地方再生: 地域と生活の社会学 [Rural revitalization from a livelihood perspective: a sociology of regions and livelihoods], edited by Sadao Tokuno 徳野貞雄 and Atsushi Makino 牧野厚史, 1–36. 福岡: 九州大学出版会 [Fukuoka: Kyūshū Daigaku Shuppankai].

Tomita, Megumi 富田恵, Yuka Ōnuma 大沼由香, Taeko Koike 小池妙子, Yūkō Kudō 工藤雄行, Fujiko Terada 寺田富二子, and Naoki Nakamura 中村直樹. 2015. “委託型の地域包括支援センター保健師のネットワーク構築に関する認識 [Perceptions of Network Building Among Public Health Nurses at Outsource-type Comprehensive Community Support Centers].” 弘前医療福祉大学紀要 [Bulletin of Hirosaki University of Health and Welfare] 6(1): 91–8.

Traphagan, John. 2020. Cosmopolitan Rurality, Depopulation, and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in 21st Century Japan. Amherst, MA: Cambria Press.

Tsujinaka, Yutaka, Robert Pekkanen, and Hidehiro Yamamoto. 2014. Neighborhood Associations and Local Governance in Japan. London and New York: Routledge.

Tsutsui, Takako. 2014. “Implementation Process and Challenges for the Community-Based Integrated Care System in Japan.” International Journal of Integrated Care 14. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3905786/pdf/IJIC-14-2014002.pdf.

Wake, Junko 和気純子. 2014. “支援困難ケースをめぐる3職種の実践とその異同 : 地域包括支援センターの全国調査から [Differences and Similarities of the Practice among the Three Professions in Responding to the Complex Needs of the Community-dwelling Elderly: Through a Nationwide Survey to the Community Integrated Care Center].” 人文学報社会福祉学 [Journal of Humanities. Social Welfare Studies] 30: 1–25.

Waldenberger, Franz, Gerhard Naegele, Tomoo Matsuda, and Hiroko Kudo (eds.). 2022. Alterung und Pflege als kommunale Aufgabe: Deutsche und japanische Ansätze und Erfahrungen. Dortmunder Beiträge zur Sozialforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Wilhelm, Johannes. 2020. “Das Grasland von Aso zwischen gesellschaftlicher Schrumpfung und Landschaftserhalt.” In Japan 2020: Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, edited by David Chiavacci and Iris Wieczorek, 222–249. Munich: Iudicium.

Yamaura, Yōichi 山浦陽一 and Kazunobu Tsutsui 筒井一伸. 2022. 地域福祉における地域運営組織との連携 [Regional Welfare and the Cooperation with Regional Management Organizations]. 東京: 筑波書房 [Tōkyō: Tsukuba Shobō].

Zenshakyō (Zenkoku shakai fukushi kyōgikai) 全国社会福祉協議会, Chiiki fukushi suishin iinkai 地域福祉推進委員会, and Zenkoku borantia, shimin katsudō shinkō sentā 全国ボランティア市民活動振興センター. 2020. 社会福祉協議会活動実態調査等報告書 2018 [Report of the Survey of the Activities and Current State of Social Welfare Councils 2018]. 東京: 東京都同胞援護会 [Tokyo: Tokyo Compatriots Aid Association].

Zenshakyō (Zenkoku shakai fukushi kyōgikai) 全国社会福祉協議会. 2023. “地域福祉について [About regional welfare].” 分野別の取り組み:地域福祉・ボランティア [Initiatives by Sector: Community Welfare and Volunteerism], accessed February 27 2023. https://www.shakyo.or.jp/bunya/chiiki/index.html.

Appendix (List of interviewees)

- This term combines the concept of “regional welfare” (chiiki fukushi) with the common expression of “region-making” (chiiki-zukuri). Our respondents referred to their efforts to “make” or “promote” regional welfare based on mutual support in various ways. Variants of the combination of regional welfare and region-making are used elsewhere as well, see e.g., “fukushi-zukuri wa chiiki-zukuri”, Matsumoto-shi Fukushi Seisaku-ka 2021.

- The government defines the socio-spatial arenas for community-based integrated care systems vaguely as “everyday living areas” (nichijō seikatsu-ken), roughly equivalent to junior high-school districts, i.e., about 100,000 inhabitants on average (Niki 2019). In less populated rural areas such as Aso, this translates into larger areas with fewer inhabitants.

- In the Aso region, these leaders are typically referred to as kuchō (responsible for a whole administrative district (gyōseiku/chiku) or hanchō/burakuchō (responsible for subsections of gyōseiku/chiku, called han or buraku) On neighborhood associations in local governance, see Pekkanen, Tsujinaka, and Yamamoto 2014.

- Gate-ball is a popular sport for older adults in Japan, see e.g., Prochaska-Meyer, Kieninger, and Nutz 2014.

- This observation is not restricted to the Aso region, see e.g. Miyake and Iseki (2014).

- As of September 2022, the Aso region saw 7,520 new COVID-19 infections since the outbreak of the pandemic, with the western parts Aso-shi (3,284), Minamiaso-mura (1,173) and Nishihara-mura (1,067) having the highest numbers (Tōkai Daigaku 2022).

- See Gagné 2020 on “delayed recovery” and social isolation after the triple disaster devastating large parts of the Tohoku region on March 11, 2011.