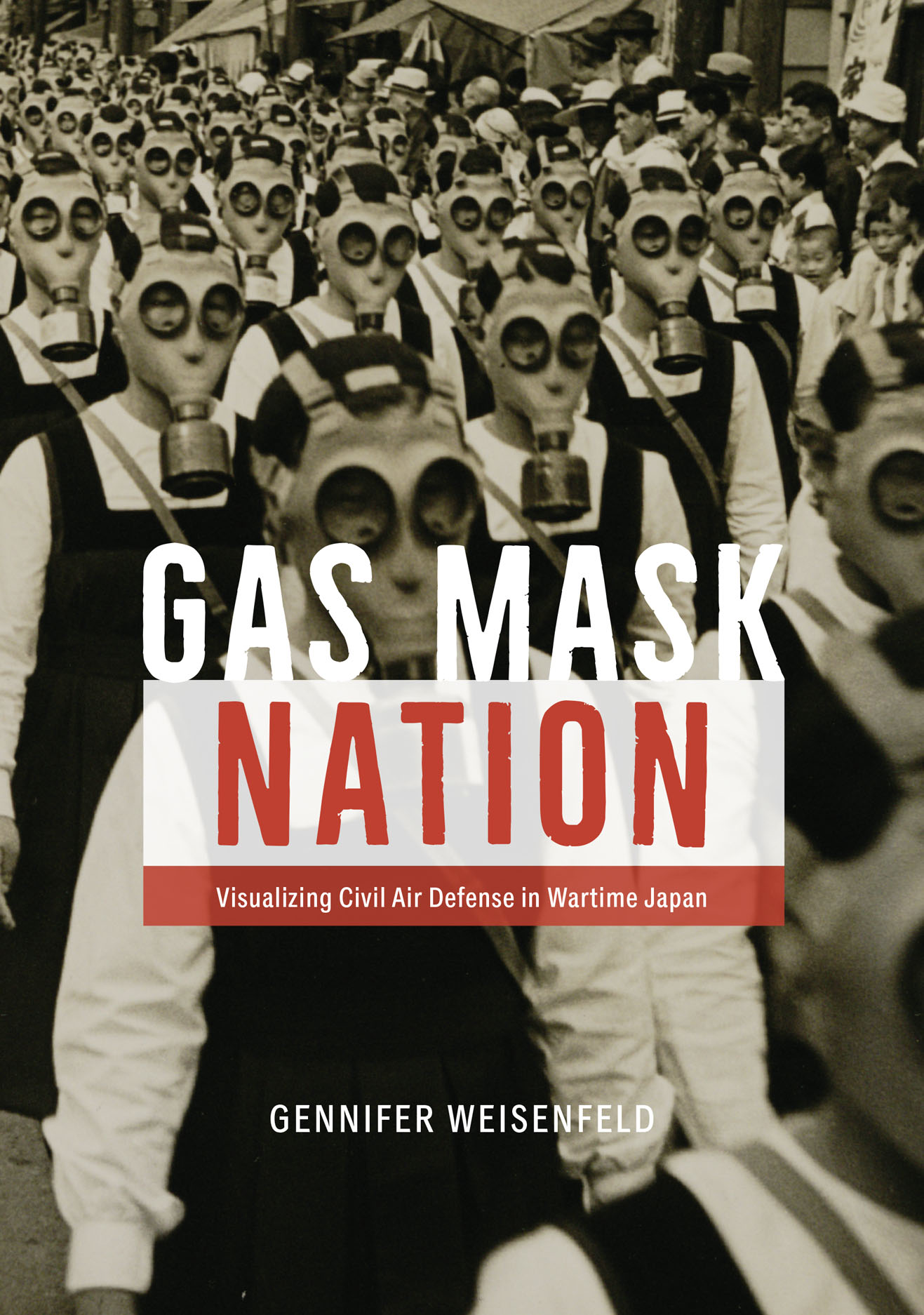

An extraordinary photograph by well-known modernist photographer Horino Masao depicting schoolgirls parading in gas masks through the Ginza in 1936 launched me into this project. That is why it sits on the cover of my book (Fig 1). The questions this image elicited, particularly the ambivalent symbolism of the gas mask as a technological instrument of protection and a grotesque fetish of monstrous transformation, sent me on a journey of curiosity that revealed a wide-ranging air defense (bōkū) movement permeating every aspect of Japanese culture from the 1930s through the end of the war. The Japanese government, along with many businesses, utilized rich and creative marketing campaigns to sell, engage, and prepare the public for the possibility of war from the air. And while I found the expected patriotic posters illustrating how model citizens should prepare their homes and bodies, and the propaganda pieces warning of the horrors that could come if lights were not properly blackened out during an air raid, I also discovered a surprising assortment of aestheticized imagery, some even humorous, that went far beyond this usual wartime patriotic fare. The volume of production was staggering. I began to see the widespread creative investment in communicating air defense to the Japanese people.

Japan’s lively mass culture blurred the boundaries between art, commerce, and national propaganda. Whether it was in designing attractive badges for successful completion of drills and short courses on air defense or innovations in fashion to keep bodily protection stylish, aesthetics and creativity were crucial for air defense mobilization. There were magazines sporting covers designed by established artists, popular candies sold with paper gas mask kits as free giveaways for children, department store window displays, kimonos decorated with images of airplanes and other weapons — and even a theme park where visitors could take part in aerial bombing. I quickly realized that to understand Japan’s social mobilization for war, I had to examine the 1930s official and unofficial culture of civil air defense and how its multivalent imagery, with roots in the mass culture of the previous decade, powerfully mediated the experience of wartime. Gas Mask Nation explores this multilayered construction of an anxious yet perversely pleasurable visual and material culture of Japanese civil air defense. It investigates these layers through a diverse range of artworks and media forms. Most centrally, it reveals the immersive and performative nature of the culture of civil defense as Japan’s loyal imperial subjects were mobilized dutifully to enact highly orchestrated, large-scale air-defense drills (bōkū enshū, also bōkū kunren) throughout the country on a regular basis.

Prevailing scholarship still portrays the war years in Japan as a landscape of privation where consumer and popular culture—and creativity in general—were suppressed under the massive censorship of the war machine. Without denying the horrors of total war, I argue that we must revise this understanding of the cultural climate. By grasping the full nature of wartime’s all-encompassing sensory and compensatory enticements, we can unmask the dangers of its mix of sacrifice and gratification.

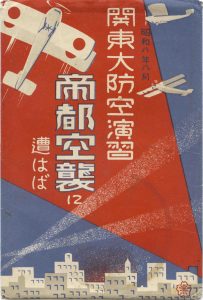

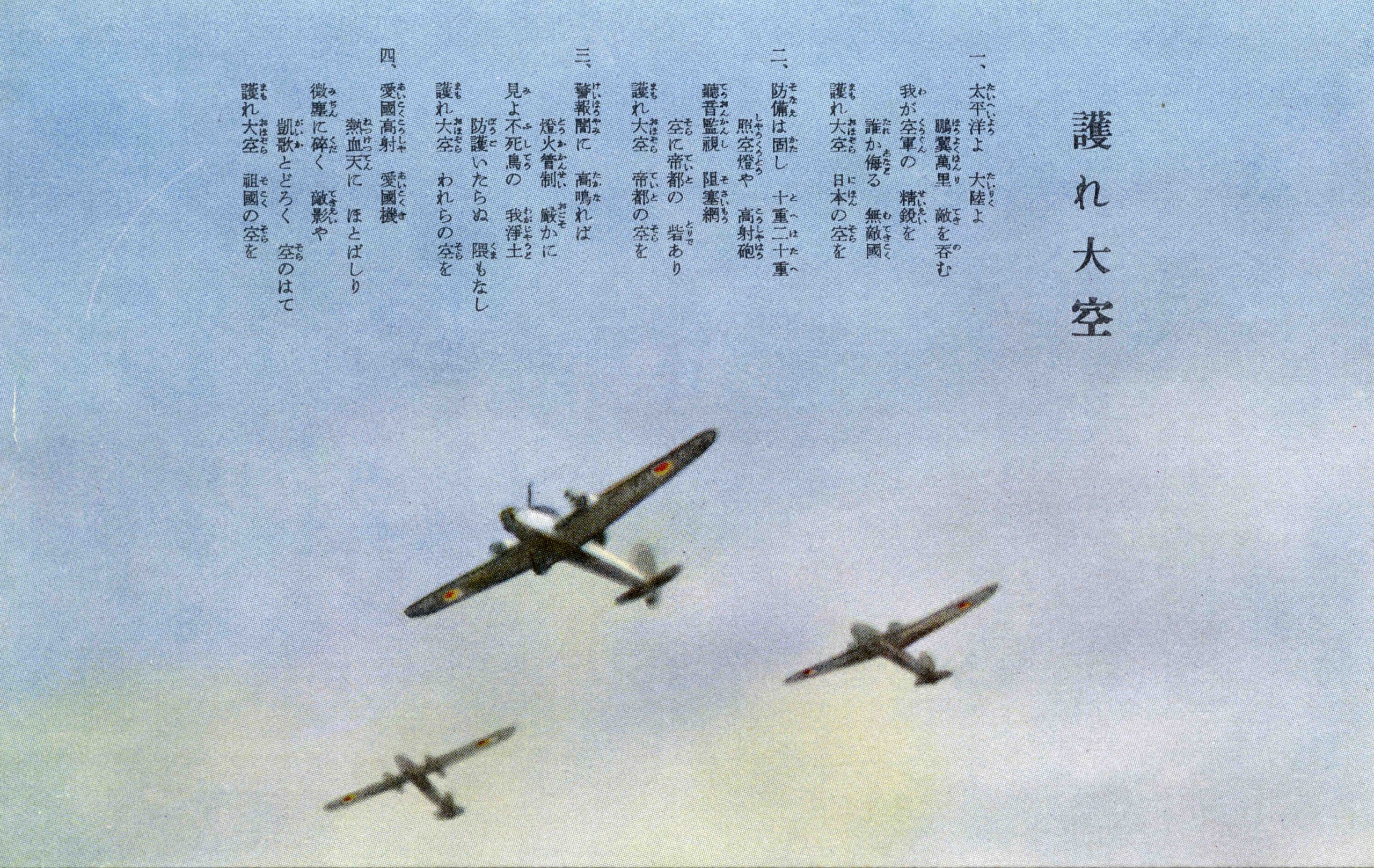

The concerns that produced Japan’s air-defense drills and images spurred the national campaign “Protect the Skies” (“Mamore ōzora,” 護れ大空), which the government introduced in 1933 with an upbeat popular song. The army captain Machida Keiji penned the lyrics, and the well-known composer Eguchi Yoshi wrote the music. The catchy tune, issued by Columbia Records, soon echoed through the halls. Such songs were both auditory entertainment and visual stimuli since the lyrics were circulated in print with evocative illustrations of airplanes and aviators. For example, the stanzas of “Protect the Skies” were emblazoned on a sky-blue postcard amid a squadron unit of three airplanes in perfect formation soaring triumphantly into the clouds (Fig 2). This multisensory approach obliges us to look beyond print and visual culture as isolated entities to a more complex network of modes that engaged all the senses. Bōkū culture was inherently multimodal since it mixed textual, visual, aural, haptic, embodied, and spatial elements in a variety of media forms.

For the Japanese government, two groups were involved in air defense: first, the army and navy were responsible for preventing attacks; and second, civilians were charged with ameliorating damage and tending to the injured. The latter, commonly referred to as kokumin bōkū or minbōkū, which prompted the formation of regional and neighborhood air-raid defense corps (bōgodan) starting in September 1932, is the primary focus of Gas Mask Nation, although the two are inextricably linked. In fact, linking them was a primary government objective. This book concentrates on the period of social mobilization and anxious anticipation before air raids shifted from fearful specter to deadly reality. This extended period of anticipatory social mobilization that inculcated vigilance through the absorbing affective experiences of civil air defense has not been adequately explored.

In April 1937, the Japanese government, inspired by Germany, promulgated a formal Air-Defense Law (Bōkūhō) specifying twenty-two points necessary for national preparation. These preparations began immediately for implementing a full-scale civil-defense drill in the capital the following year. The plans were greatly accelerated after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July 1937 that incited the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The preparations and drills were then implemented on October 1, 1937, which launched a major national civil air-defense campaign as part of a larger social-education propaganda effort. This campaign included visually striking, creatively designed publicity and several prominent exhibitions to inculcate the “air-defense mindset” among the public. The Air-Defense Law codified military and civilian obligations, for the latter outlining measures required for blackouts, firefighting, protection against gas attack, evacuation, first aid, surveillance, and an air-raid alarm system, as well as the monitoring of communication and warnings needed for implementation of these measures. The vivid displays at exhibitions reveal the power of publicly exhibiting bōkū.

In April 1939, the Home Ministry established the Greater Japan Air-Defense Association (Dai Nippon Bōkū Kyōkai) to inculcate its national defense policies, including biweekly publication of Protection of the Skies (Sora no mamori) magazine from 1939 to April 1943. Heavily illustrated, Protection of the Skies was a paean to the civil air-defense movement. Global in scope, it surveyed the culture of air defense throughout the world among friends and foes. And despite its dark and violent subject matter, the magazine conveyed an astonishing dynamism that also spoke to a creative investment in these topics. This and other air defense journals were designed to be enticing and provide visual pleasure even in the midst of stress and hardship. Wartime offered a contradictory mixture of pain and pleasure.

Bōkū Publicity and Memorabilia: Postcards of Drills, Weapons, and the War of the Future

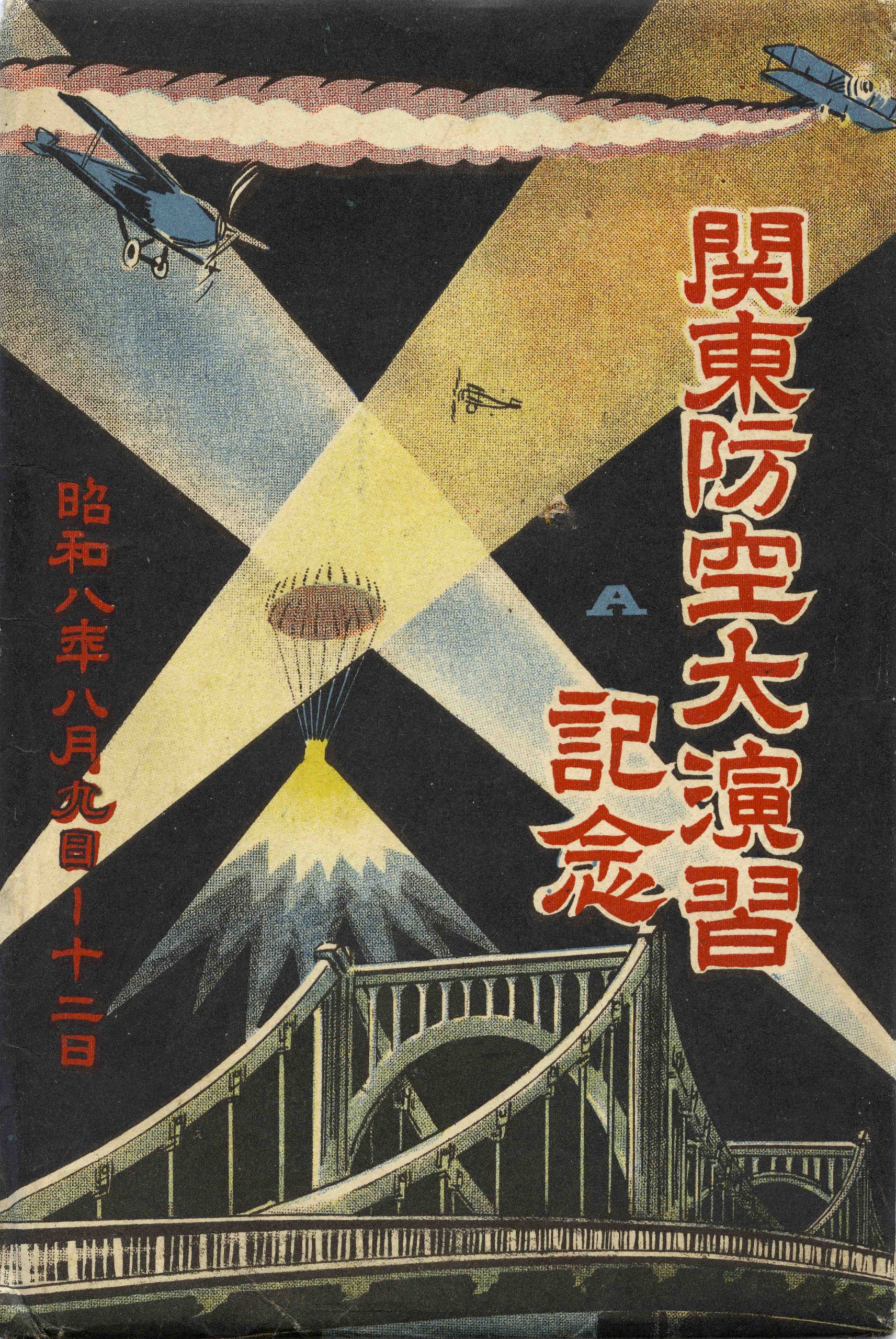

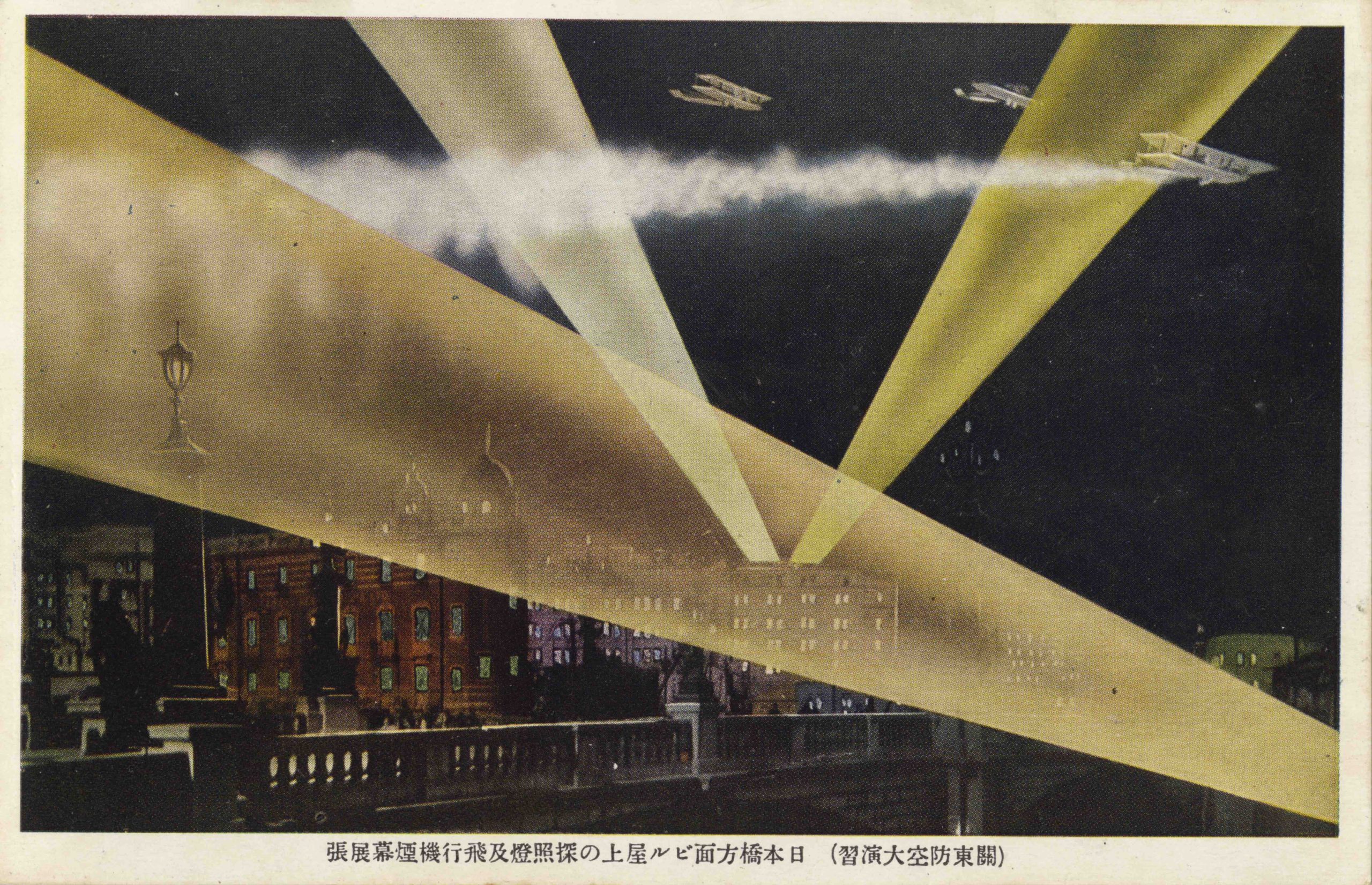

Tokyo held a major regional defense exercise from August 9 to 11, 1933, less than six months after Japan withdrew from the League of Nations to protest being officially censured for its activities in Manchuria. The event was billed in the press as fundamentally different from previous exercises because it would simulate “real battle” conditions employing both military and civilian defense corps. In conjunction with these drills, entrepreneurs and official organizations issued sets of commemorative postcards employing dramatic aesthetics and catering to a burgeoning consumer market for bōkū memorabilia as collectibles. Below I will expand on three sets of postcards issued as souvenirs for the 1933 Great Kantō Air Defense Drills and after. These visual souvenirs depict a bōkū visual canon that appeared widely across all media genres. As part of the larger campaigns for air defense itself, they tapped into the exciting, and often darkly enticing, visual rhetoric of national defense by deploying what I have termed its “objects of attraction”: airplanes, gas masks, bombs, and all the wondrous weapons of war.

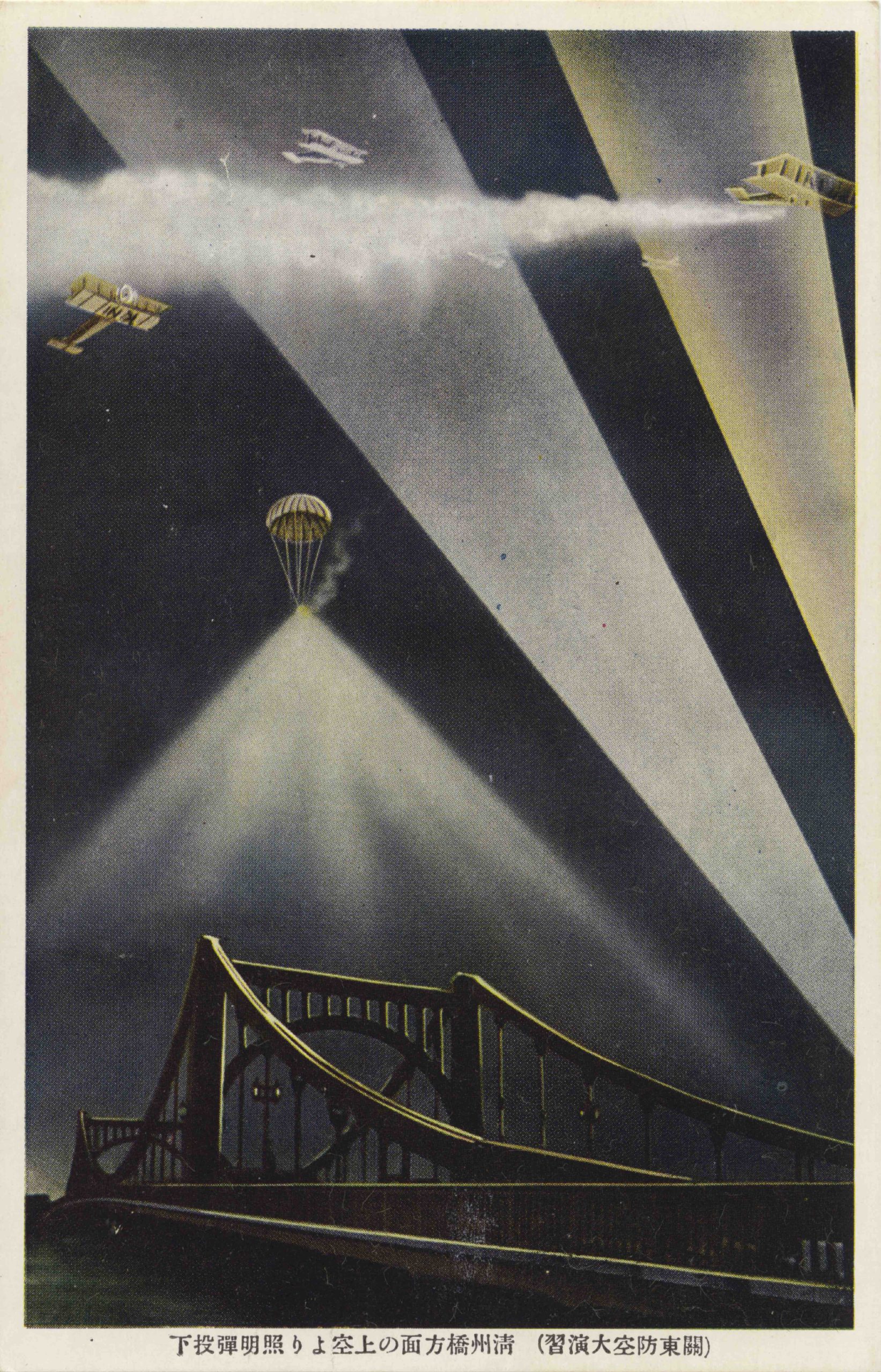

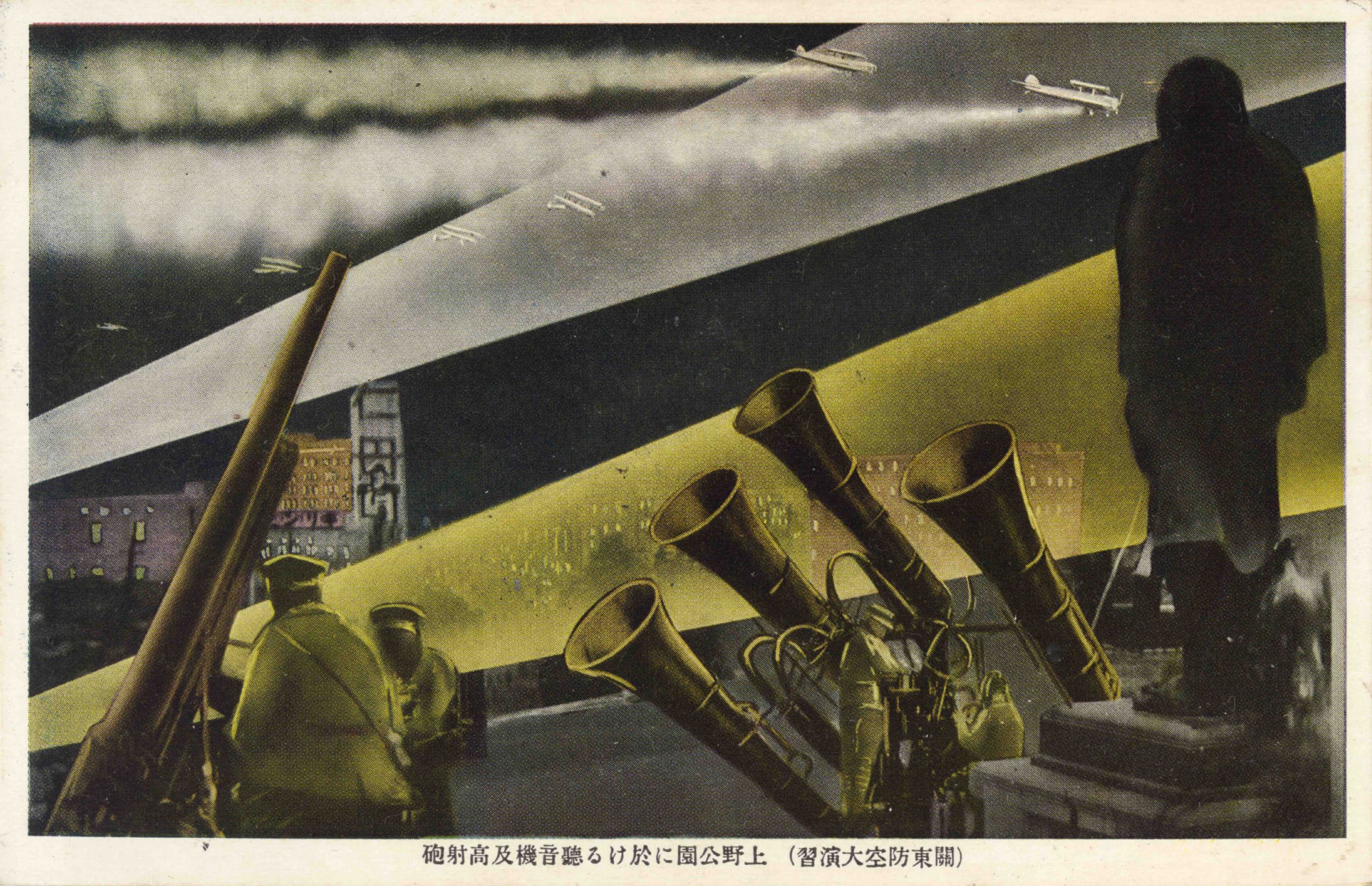

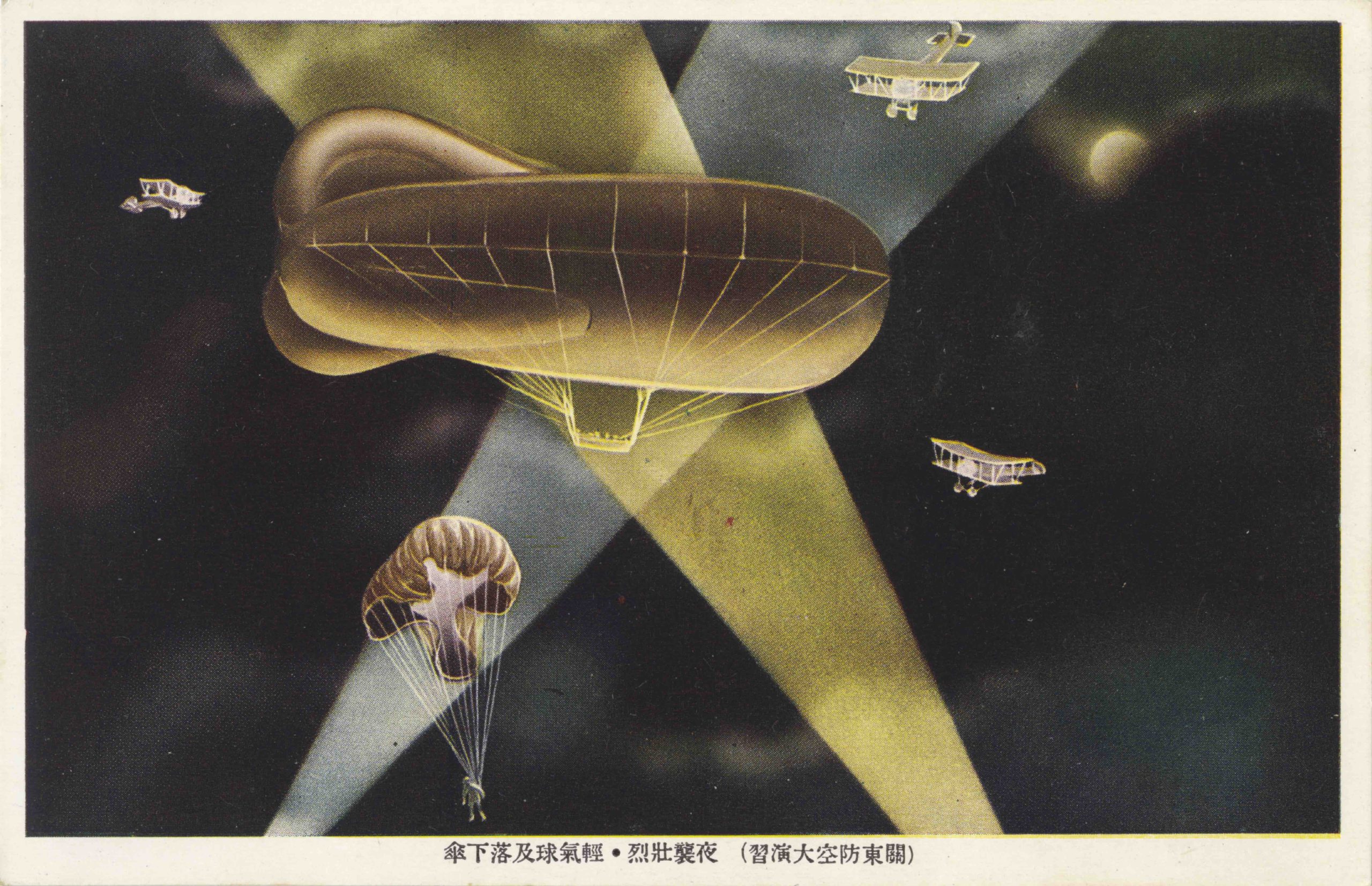

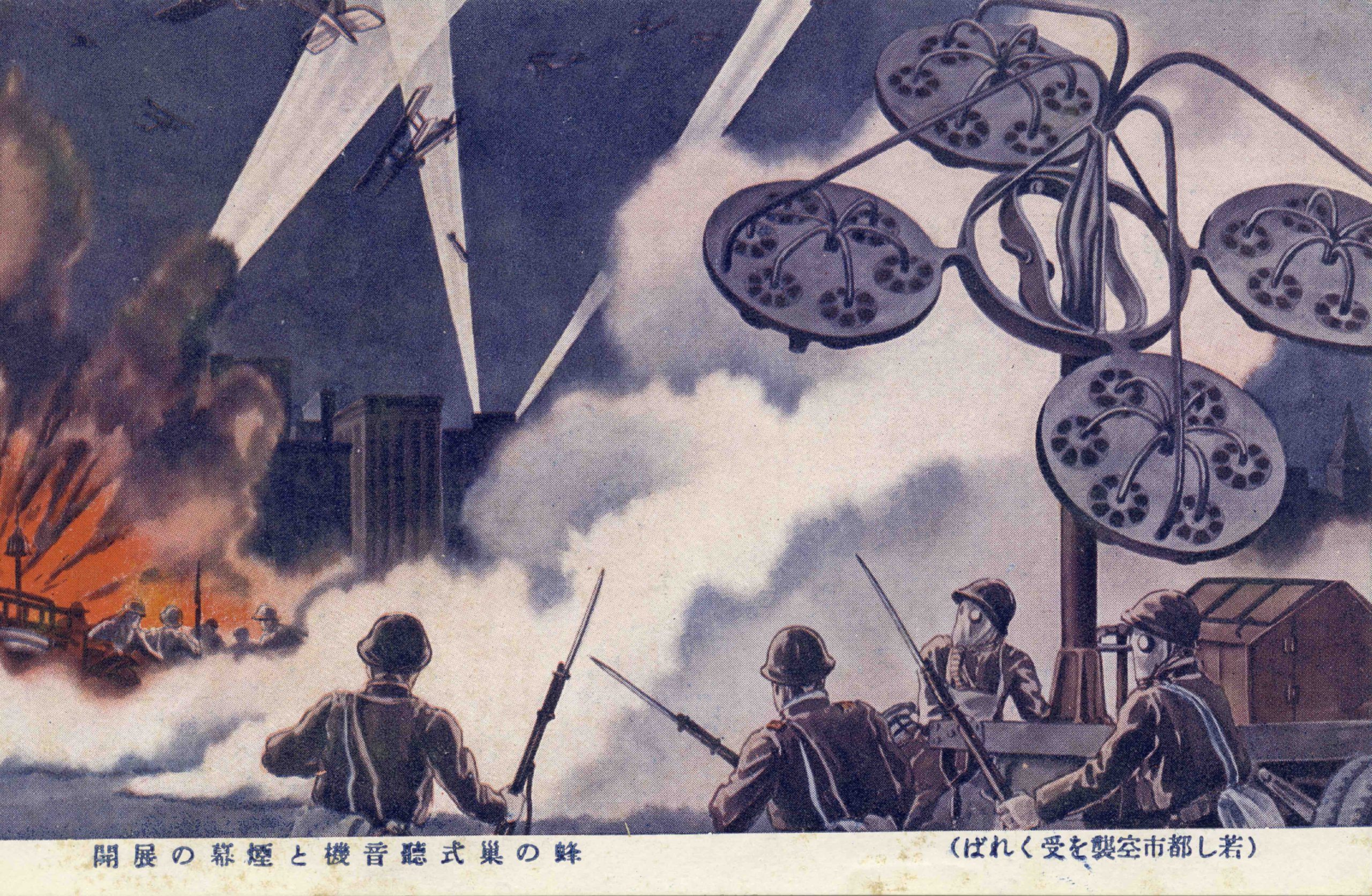

Symbols of power and dominance, airplanes were transcendentally beautiful. In fact, airplanes dominated the early twentieth-century visual field across the world. They were sublime objects appreciated both for their aesthetic qualities as well as for their technological marvels. They feature prominently in the visualization of air defense as scientific wonders and phantoms of death. In the early 1930s, speculative fiction air-defense novels portraying future war became a popular literary genre. This was just one subgenre of popular literature that a broad audience read eagerly. Postcards depicting air defense drills channeled speculative and science fiction in depicting the war of the future. This included bombs, barrage balloons, antiaircraft guns, searchlights, “the eyes of the air-defense war,” and large tuba- or disc-shaped acoustic locators (chōonki), “the ears of the air-defense war,” devices for amplifying the sound of approaching enemy aircraft. This panoply of instruments of defense and destruction were objects of wonder.

FIGURES 3-11 (Click to expand)

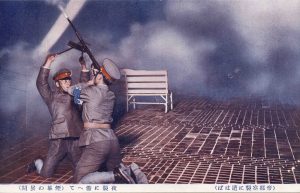

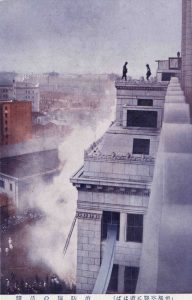

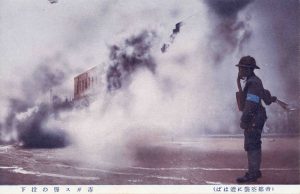

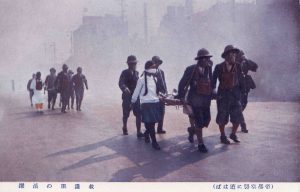

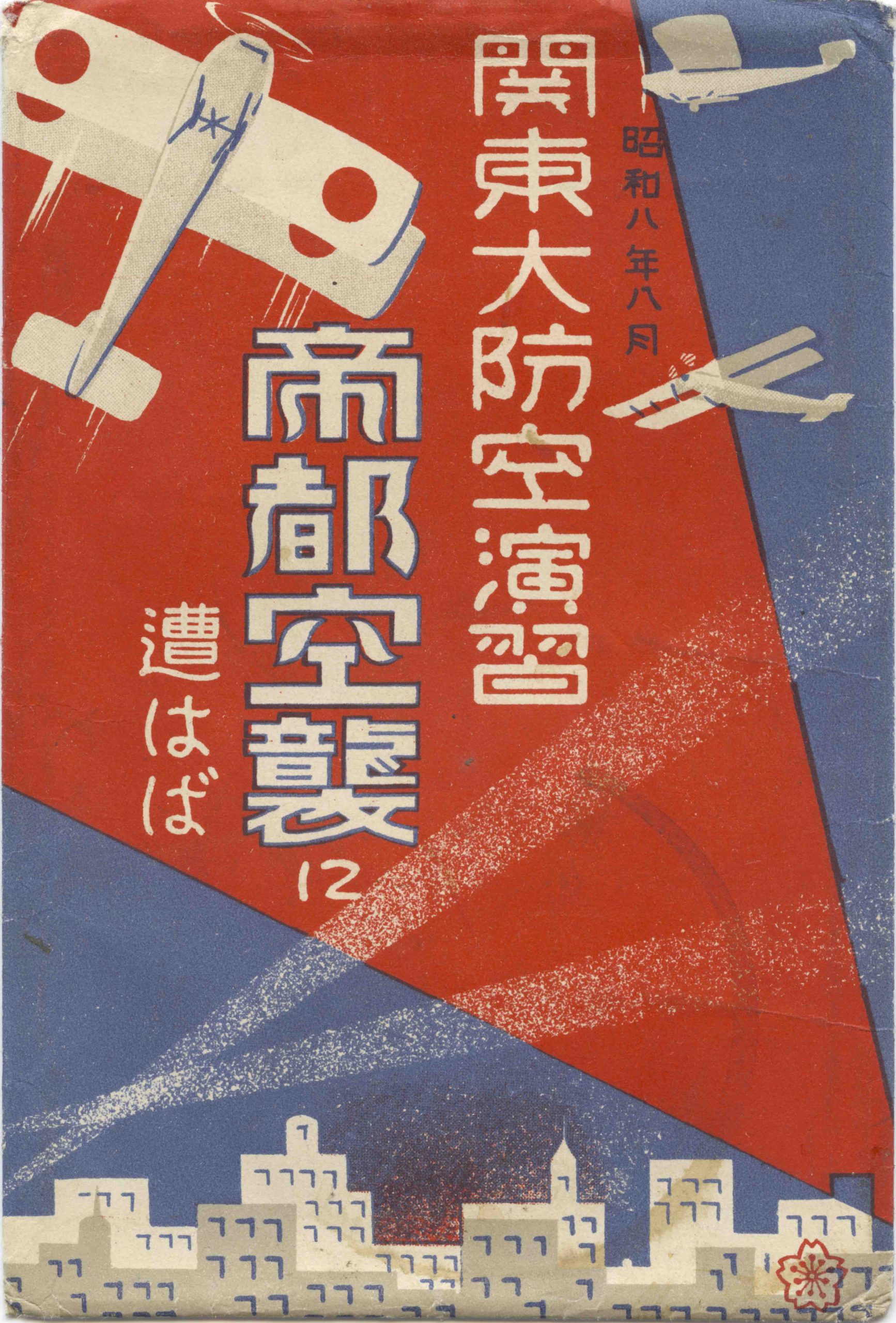

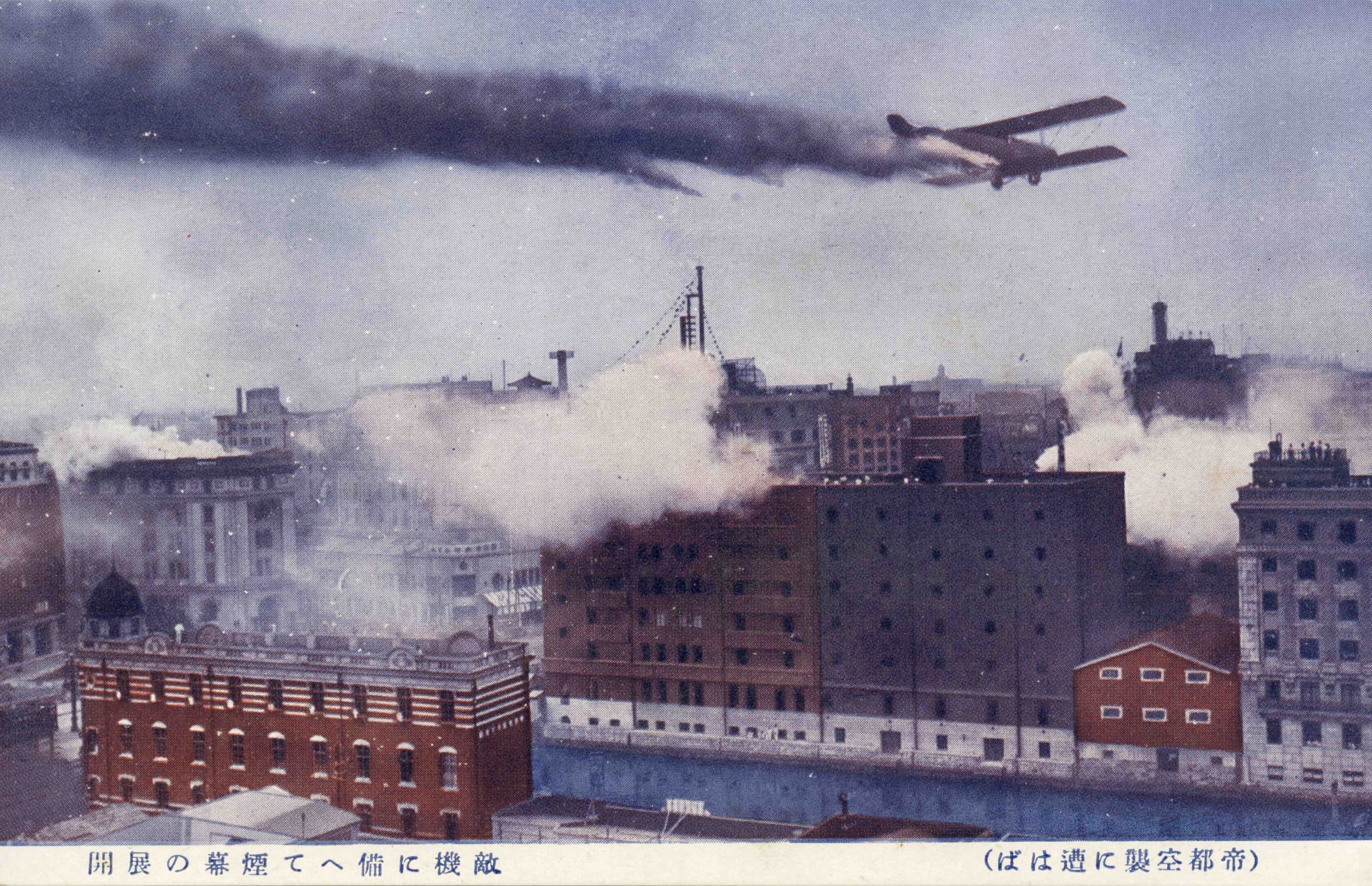

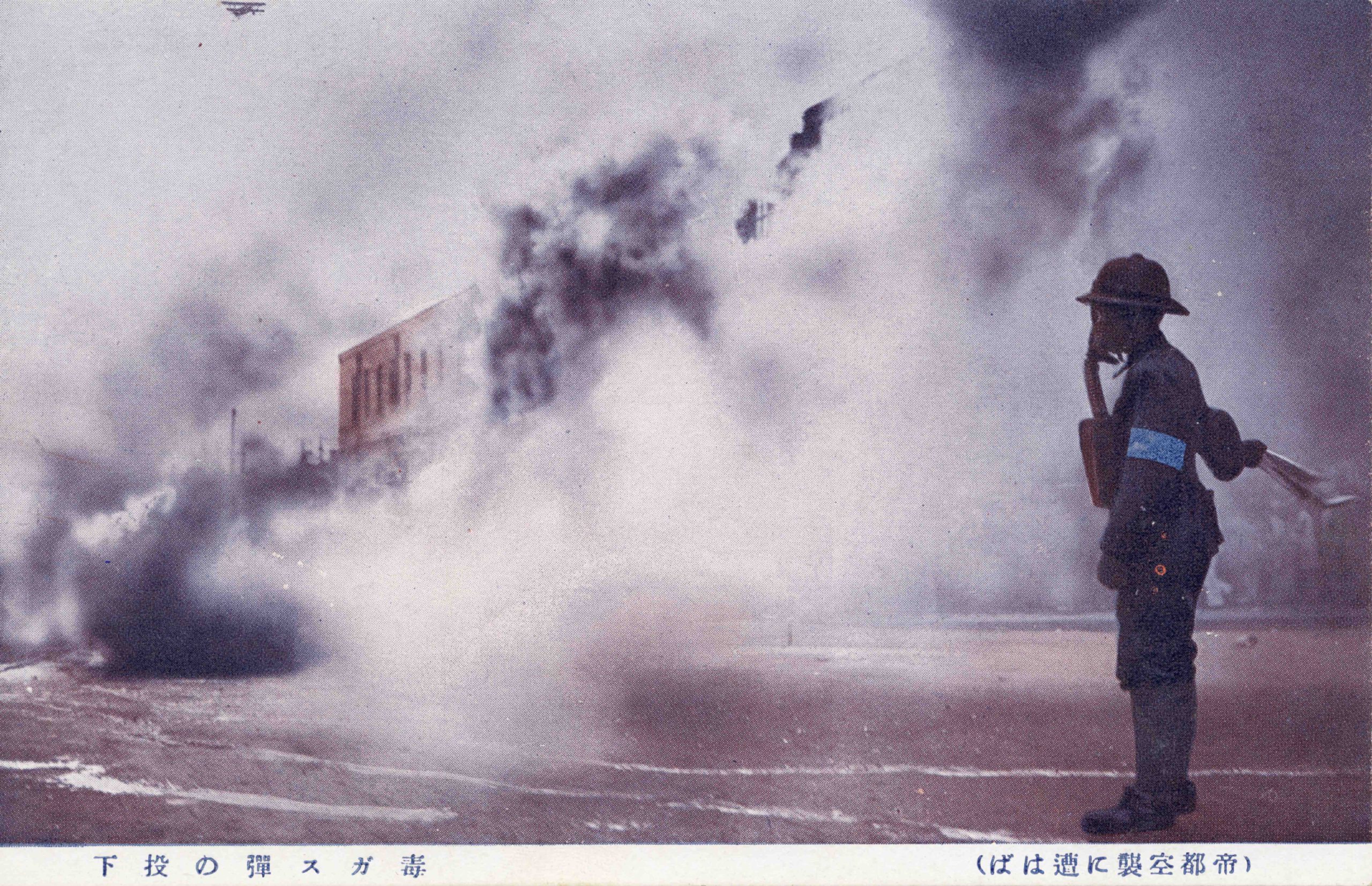

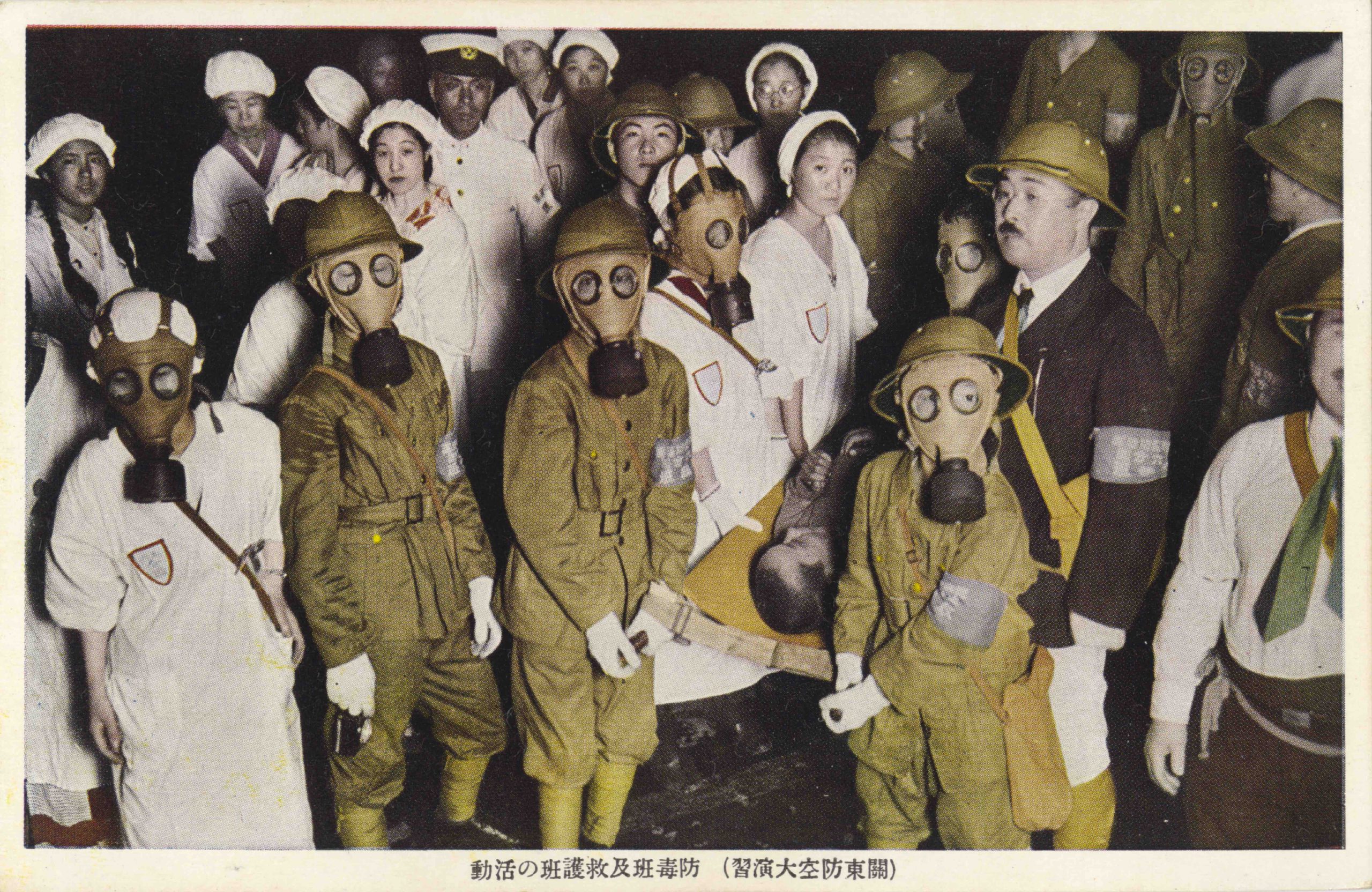

Here we have two sets of eight postcards issued to commemorate the 1933 Great Kantō Air Defense Drills (Kantō Dai Bōkū Enshū) held in early August. The cover envelope for one subtitled “If We Encounter an Air Raid in the Imperial Capital” (Teito kūshū ni awaba) shows the bold cone of a searchlight in bright red illuminating Japan’s airplanes dramatically engaged in a mock raid above Tokyo (Fig 3). The postcards inside show photographs of airplanes dropping explosives with huge plumes of smoke described as “real bombings” in “real conditions” (Fig. 4) They document a defensive aircraft emitting a smokescreen (enmaku) to camouflage the city from enemy bombers (Fig. 5). Under the cover of this smokescreen, Japanese soldiers on the ground prepare for a night raid with antiaircraft artillery (Fig. 6). A high-rise building shows fire-fighting crews engaged in putting out conflagrations on the roof and with a ladder to crews below (Fig. 7). Soldiers in gas masks stand ready in the streets, the red bands on their caps coordinated with the brightly colored details on their uniforms. (Fig. 8) One masked soldier stands at attention as a plume of simulated toxic gas (from smoke canisters) spews diagonally into the street around him (Fig. 9). An army of gas-masked responders then rush to spread powder to neutralize (chūwa sagyō) the clouds of poison gas in the streets (Fig. 10). Groups of men and women, soldiers in gas masks and schoolgirls with gauze masks along with adult women in aprons and gas masks, carry stretchers to evacuate and treat the wounded (Fig. 11). The photographic scenes are shot at ground level, designed to put the viewer in the middle of the action, accentuating the real life-and-death drama through acute angles and close cropping.

FIGURES 12-20 (Click to Expand)

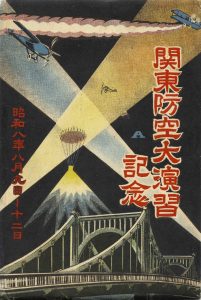

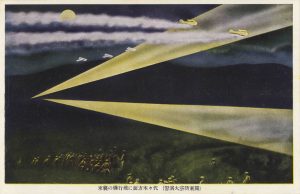

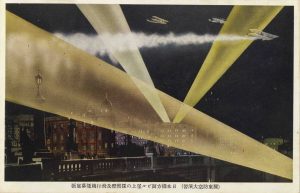

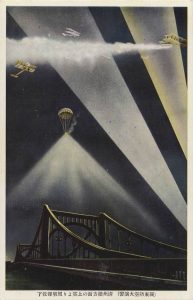

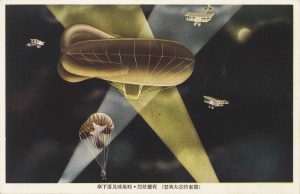

Another set simply titled “Great Kantō Air Defense Drills Commemoration” (Kantō Dai Bōkū Enshū Kinen) uses a mixture of photography and hand-rendered imagery and coloring to accentuate the futuristic landscape of the nighttime air raid (Fig. 12). The envelope shows an evening scene with gold and silver-tinted crisscrossing searchlights that illuminate aircraft streaming smoke and a descending parachute over Tokyo’s iconic Kiyosubashi steel bridge spanning across the Sumida River. Postcards in the set show photographic documentation of smokescreens (Fig. 13) tightly packed groups of nurses and gas-masked responders, many young boys, tending to those wounded by poison gas (Fig. 14), expansive views of the dramatically illuminated sky over Yoyogi (Fig. 15), and views looking toward well-known landmarks near Nihonbashi (Fig. 16), Kiyosubashi (Fig. 17), and in front of the Imperial Palace (Fig. 18). Ueno Park is shown with anti-aircraft guns and golden acoustic locators at the ready (Fig. 19). One particularly futuristic skyscape features a gleaming barrage balloon captured in crossed searchlight beams surrounded by flying aircraft and a descending parachutist (Fig. 20). Many of the scenes show a luminous moon lyrically illuminating these ominous vistas.

FIGURES 21-28 (Click to Expand)

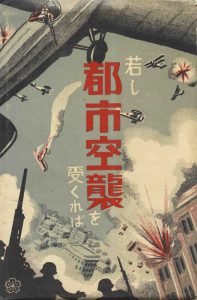

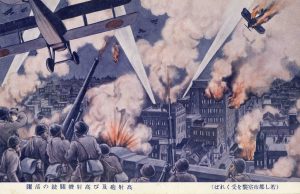

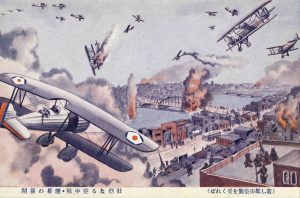

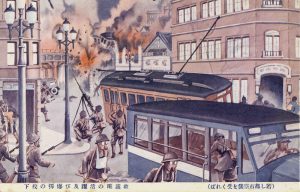

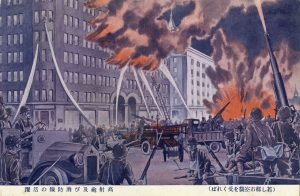

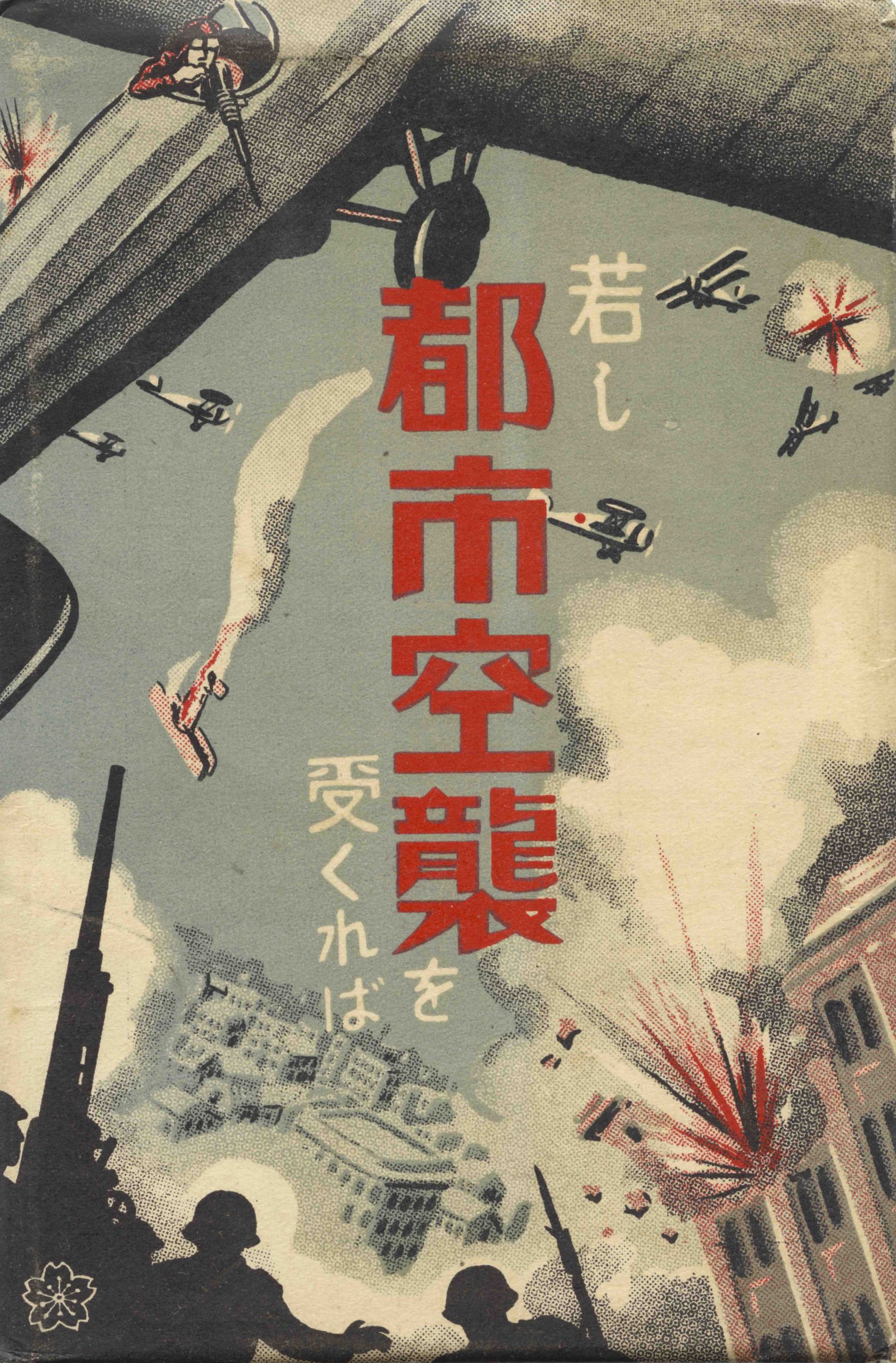

An undated postcard set portentously titled If We Have an Urban Air Raid from the 1930s imagined scenarios of a future urban bombing. It quickly took the viewer to a fictional battlefront of hellish destruction and heroic defense (Fig. 21). Antiaircraft artillery and machine guns in action (Fig. 22). Fierce aerial warfare and smokescreen deployment (Fig. 23). Rescue team activity and dropping bombs (Fig. 24). Antiaircraft artillery and firefighting (Fig. 25). Neutralizing highly poisonous gas and antiaircraft machine guns and artillery (Fig. 26). Searchlights in the sky, trumpet-shaped acoustic locators, and firefighters (Fig. 27). Honeycomb-style acoustic locators and smokescreen deployment (Fig. 28). The imaginative pleasure conveyed by such colorfully hand-rendered dystopian images and stories of future war, including their wondrous technological contraptions, far exceeded any claims of sheer utility. Like science fiction, they offered a shared adventure of bodily engagement that appealed to the imagination, taking hold in the vibrant youth market of mass culture but extending well beyond it to adults. Its futuristic orientation fused the war of the present with the war of the future. Air-defense culture also directly engaged play to create sensory and imaginative extensions. While mass culture was becoming full of civic alarm, official culture was incorporating imaginative play and creativity to entice the masses.