Abstract: At the White House Festival of the Arts in 1965, the American novelist John Hersey read excerpts from his noted non-fiction work Hiroshima (1946) as an act of protest against President Lyndon Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War. As Hersey linked Harry Truman’s bombing of Hiroshima and Johnson’s bombing of Vietnam within the same spectrum of American military interventions in Asia, he earned the ire of the First Family and raised questions about freedom of speech in the White House itself. Drawing on archival documents in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and the Library of Congress, this article argues that Hersey’s literary protest revealed how the premises of cultural freedom that lay at the heart of Cold War American liberalism stirred far more controversy in practice than their placid articulation in theory would have ever suggested.

Keywords: Hiroshima, Cold War, Vietnam, protest, cultural freedom

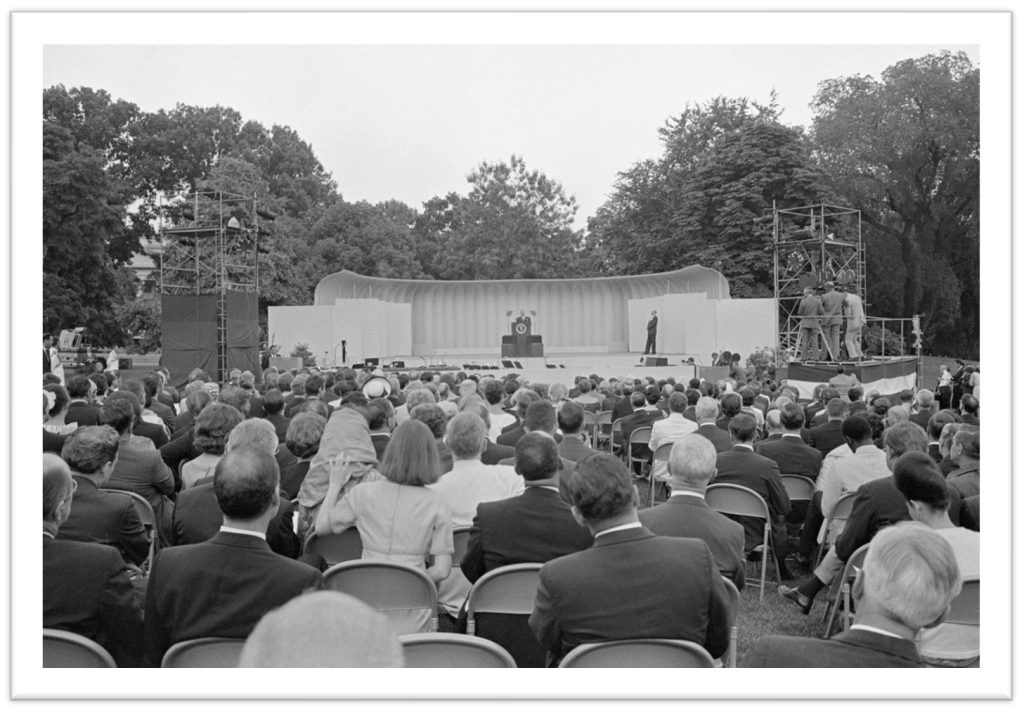

Preparations for the White House Festival of the Arts, June 13, 1965

White House Photo Office Collection, 1965-06-13-34580, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas.

On June 14, 1965, President Lyndon Baines Johnson and the First Lady hosted the White House Festival of the Arts, a one-of-a-kind event that brought together the realms of postwar American culture and politics like never before. The purpose of the event was to celebrate contemporary American literature, film, painting, sculpture, photography, theater, music, and dance by inviting prominent representatives from each of these artistic fields—along with numerous others who supported the arts without being artists themselves—to the White House for a one-day showcase of American culture. By building a bridge between Johnson’s White House and the cultural community, the event was intended to publicize Washington’s support for the arts that would later be formalized when Johnson signed the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act in September 1965, which led to the creation of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts.1 At the core of both the Festival and the legislation was the seemingly noncontroversial idea that the American government supports the creative freedom of artists and intellectuals. “In no country in all the world—East or West—is the artist freer than here in America,” Johnson declared at the Festival (Johnson 1965, 1).

The Festival of the Arts became a disaster for the White House, however, when a vocal minority of invitees used the event as a platform to protest Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War. The historian Mark Atwood Lawrence observes that in the months after Johnson won the November 1964 Presidential election, he dramatically expanded American military operations in Vietnam, committing combat troops to South Vietnam on the ground and initiating the sustained bombing campaign over North Vietnam known as Operation Rolling Thunder through the air (Lawrence 2008, 88). Lawrence notes that Johnson tried to conceal the true implications of his escalations of the war by downplaying it in public statements, with the result being that in the end, “Johnson committed the United States to a major war without ever forthrightly saying so” (Lawrence 2008, 93). As Americans nevertheless learned of Johnson’s acceleration of United States involvement in Southeast Asia, however, some voiced their opposition to his escalations of the war in early 1965, at around the time that plans for the White House Festival of the Arts were afoot. Teach-ins, campus protests, and other criticism of Johnson all indicated pockets of disapproval in the American public.

It was another story for Johnson altogether, though, when prominent writers used their invitations to the Festival of the Arts to bring the protest to the White House itself. The trouble for Johnson began when the poet Robert Lowell wrote to the President in a letter that he also released to the press, explaining that he would refuse to attend the Festival as an act of protest against the White House. “Although I am very enthusiastic about most of your domestic legislation and intentions,” Lowell wrote to Johnson, “I nevertheless can only follow our present foreign policy with the greatest dismay and distrust… We are in danger of imperceptibly becoming an explosive and suddenly chauvinistic nation, and may even be drifting on our way to the last nuclear ruin” (Lowell to Johnson, May 30, 1965). In the days after Johnson received this letter from Lowell, another piece of protest correspondence arrived at the White House signed by Hannah Arendt, Dwight Macdonald, Mary McCarthy, Robert Penn Warren, Philip Roth, and Mark Rothko, among several others. They collectively announced that they were joining Lowell’s protest: “We who have considered ourselves friends of the administration support Robert Lowell in his decision not to participate in the White House Festival of the Arts on June 14th,” they wrote, adding that they “share his dismay at recent American Foreign Policy decisions” and that “as the weeks pass some of us have become more and more alarmed by a stance in foreign affairs which seems increasingly belligerent and militaristic” (Arendt, et al., to President Johnson, received June 5, 1965). The dissenters made their position plain in declaring: “We hope that people in this and in other countries will not conclude that a White House Arts Program testifies to approval of administration policy by the members of the artistic community” (Arendt, et al., to President Johnson, received June 5, 1965). In addition to these pieces of protest correspondence, Macdonald circulated a petition on the day of the event at the White House itself that criticized Johnson and praised Lowell (Macdonald 1993, 14).

The most provocative form of protest that was staged at the Festival, however, came from the novelist John Hersey, who opposed Johnson’s interventions in Vietnam but accepted his invitation to the White House so that he could warn the President personally about the danger of escalating foreign wars. Hersey’s method for protesting Johnson was to use the ten minutes allotted to him in the prose and poetry section of the program to read from his celebrated non-fiction work Hiroshima (1946). The book is a noted account of the personal experiences of several survivors of the atomic bomb that the United States dropped on Japan to end World War II. Hersey read portions of it at the White House as a form of protest against Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War that was intended to make the otherwise abstract effects of American foreign policy more concrete, and more human, to those in Washington who were responsible for them.

Few texts in the canon of postwar American writing could have made the human cost of American military interventions in Asia clearer than Hiroshima. The historian Kenneth C. Davis calls Hersey’s attempt to tell the story of Hiroshima from the Japanese perspective “a masterpiece of contemporary reporting. It did more to open eyes to the destructive power that man had unleashed than anything before it or anything since,” adding that “for sheer emotional impact and the power of humanizing the destructive power of the atomic bomb, Hiroshima remains unsurpassed” (Davis 1984, 127). Hersey’s Hiroshima is now regarded as a classic of modern American prose, and by 1980, there were more than four million copies in circulation, with Davis counting it among the “fifty paperbacks that changed America” (Davis 1984, 129, 391).

This essay explores what it meant for Hersey to read from Hiroshima at the White House in the age of Vietnam. Drawing on archival documents held in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and the Library of Congress, I argue that as Hersey’s act of conscience earned the ire of the White House, it inadvertently revealed how the seemingly noncontroversial ideals of American liberalism that the Festival of the Arts was supposed to embody—from freedom of speech and freedom of thought to civil discourse premised on mutual tolerance—in fact stir far more controversy in practice than their placid articulation in theory would ever suggest. In principle, after all, Hersey was merely exercising his liberal democratic right to free expression when he peacefully and eloquently protested the Vietnam War at the Festival of the Arts. But when some in the White House became uncomfortable with his participation in the event—with a few even arguing that he should not be allowed to proceed with his reading at all—Hersey’s literary protest exposed how the practice of cultural freedom became difficult to tolerate for the very White House that claimed to be its champion. As Hersey linked the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Johnson’s bombing raids over Vietnam within the same continuum of American military interventions abroad in Cold War Asia, then, he also tested the premises of cultural liberalism at home in Cold War America, revealing the complexity of the very ideals that were often said to inform the inviolable ethos and moral authority of American leadership in the free world.

Government and the Arts

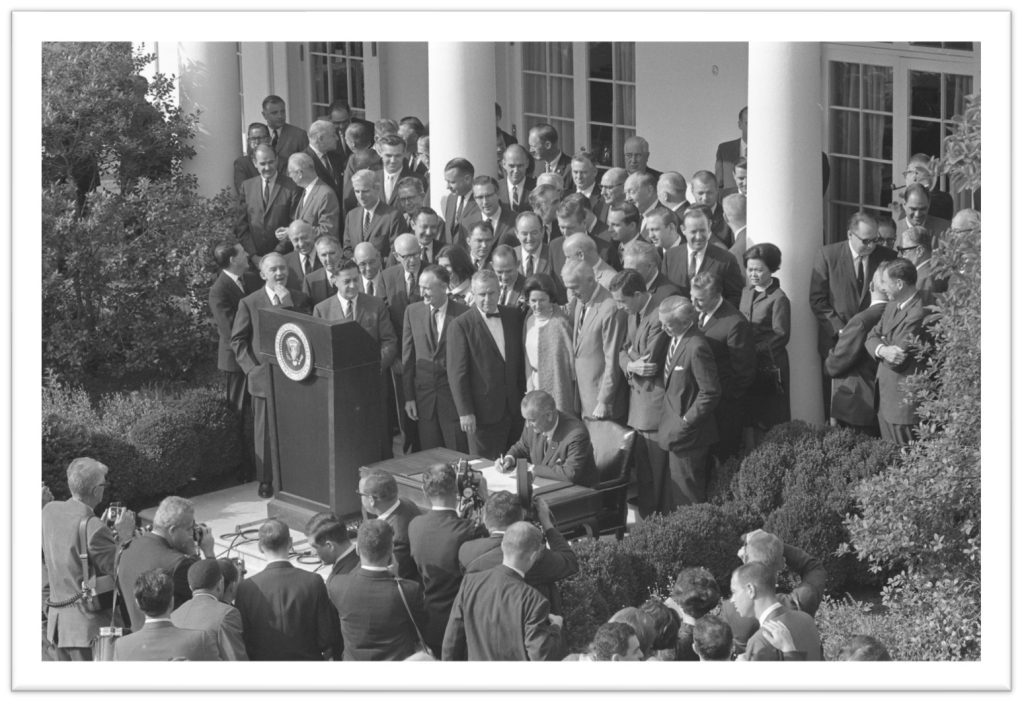

President Johnson signs the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act, September 29, 1965

White House Photo Office Collection, 1965-09-29-619, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas.

On the day that Johnson signed the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act in September 1965, he explained the significance of the legislation as a corrective to the usual hierarchy of priorities in America that had long placed the sciences over the arts. “We in America have not always been kind to the artists and the scholars who are the creators and the keepers of our vision,” he declared. “Somehow, the scientists always seem to get the penthouse, while the arts and the humanities get the basement” (quoted in Larson 1983, 217). In making this statement as part of his advocacy for federal spending on the arts and humanities, Johnson staked his position within the controversies that have long surrounded government support for culture in America.

In a study of government-administered cultural programs ranging from Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration to Johnson’s National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities, Gary O. Larson notes that federal spending on the arts and humanities has long been criticized by some for being a waste of taxpayer money. But Larson also writes that a more complex objection has held that any government interventions into the cultural sphere—including well intentioned efforts to increase federal spending and support for artists—run the risk of standardizing, bureaucratizing, controlling, and politicizing the otherwise independent spirit of the arts (Larson 1983). The fundamental problem from this point of view is that that the forms of freedom embodied by the arts present themselves in tension with the politics of control exercised by government. Larson observes that Johnson sought to ameliorate these tensions in 1965 by explicitly stating that government’s role in culture should be limited. Even as he promoted the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act, he acknowledged that “no government can call artistic excellence into existence,” and later declared that while government may nurture conditions for the arts to flourish, it must never “seek to restrict the freedom of the artist to pursue his calling in his own way. Freedom is an essential condition for the artist” (quoted in Larson 1983, 201).

Although Johnson intended for these statements to indicate that he was a friend of the artist and the scholar who championed the cause of culture in Washington, his role as arts advocate was always something of an awkward fit with his public image. In the eyes of some of his critics, after all, Johnson was a thickly accented provincial whose turn of mind rarely inclined in the direction of delicate aesthetic matters or the philosophical contemplation of contemporary art. Edwin O. Reischauer—a Harvard scholar of Japan who served both John F. Kennedy and Johnson as Ambassador to Japan from 1961 to 1966—remembered that “there was a real sense of let down” when Johnson assumed the Oval Office following Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963 because Johnson “did not have the same charismatic appeal” as his predecessor (Oral history transcript, Reischauer, 2). Reischauer said that Johnson’s Southern accent put off some of the President’s more snobbish critics—“it isn’t what they consider the educated way to talk”—and explained that when it came to dealing with scholars of “my more academic, intellectual heritage and so on, he [Johnson] didn’t have easy contact with them” (Oral history transcript, Reischauer, 19, 4).

Johnson’s distance from the worlds of academia and contemporary art were an open secret at the White House Festival of the Arts. Eric Goldman, the Princeton historian who organized the Festival while serving in the White House as “Special Consultant to the President,” frankly acknowledged that no one in the White House expected Johnson to “emerge faunlike as a devotee of the arts” on the day of the event (Goldman 1969, 420). Indeed, Goldman wrote, Johnson “simply did not take the festival that seriously” (Goldman 1969, 421). In the end, the President’s decision to greenlight the Festival without considering its potential to produce acrimony would come back to haunt him.

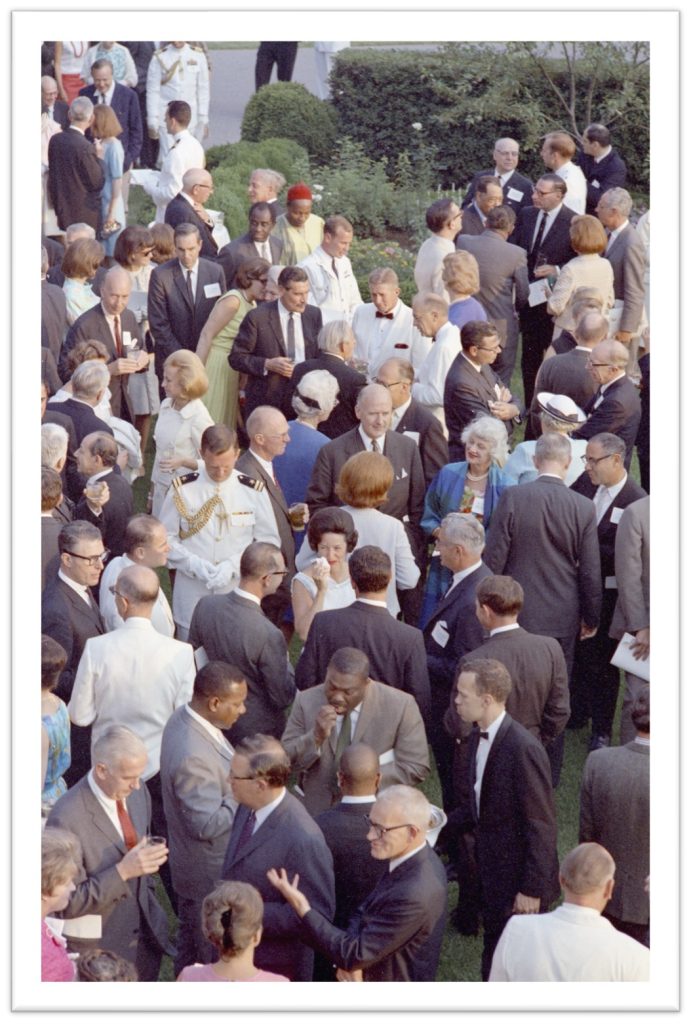

The White House Festival of the Arts

Johnson is remembered for his extraordinary ambition as President, and Goldman recalled that White House staff conceived of the Festival from the first as an event that would be “appropriately Johnsonian as an across-the-board representation of many of the arts” (Goldman 1969, 419). Some of the highlights of the wide-ranging program for the Festival include readings of prose by Saul Bellow and Hersey; Marian Anderson appearing alongside the Louisville Orchestra; Roberta Peters of the Metropolitan Opera performing Leonard Bernstein and George Gershwin; staged portions of Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie and Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman; screenings of iconic scenes from classic American films like Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest introduced by Charlton Heston; dance performed by The Robert Joffrey Ballet; jazz performed by Duke Ellington; displays of dozens of paintings by icons of contemporary American art, including Thomas Hart Benton, Willem de Kooning, Edward Hopper, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Georgia O’Keeffe, Jackson Pollack, Mark Rothko, and Ben Shahn; photography by Ansel Adams, Richard Avedon, Walker Evans, Dorthea Lange, and Eugene Smith; and sculptures by Isamu Noguchi and several others (Program for the White House Festival of the Arts 1965). In addition to the performances and art exhibitions, remarks by policy expert George Kennan, Lady Bird Johnson and the President himself affirmed the public relevance of the arts in American society.

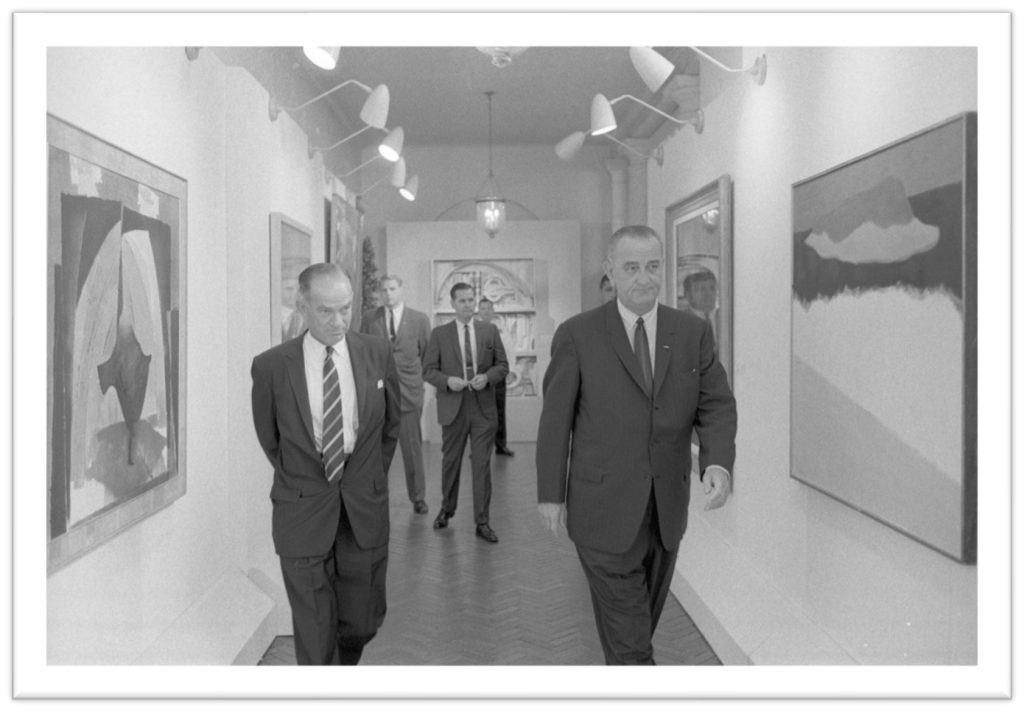

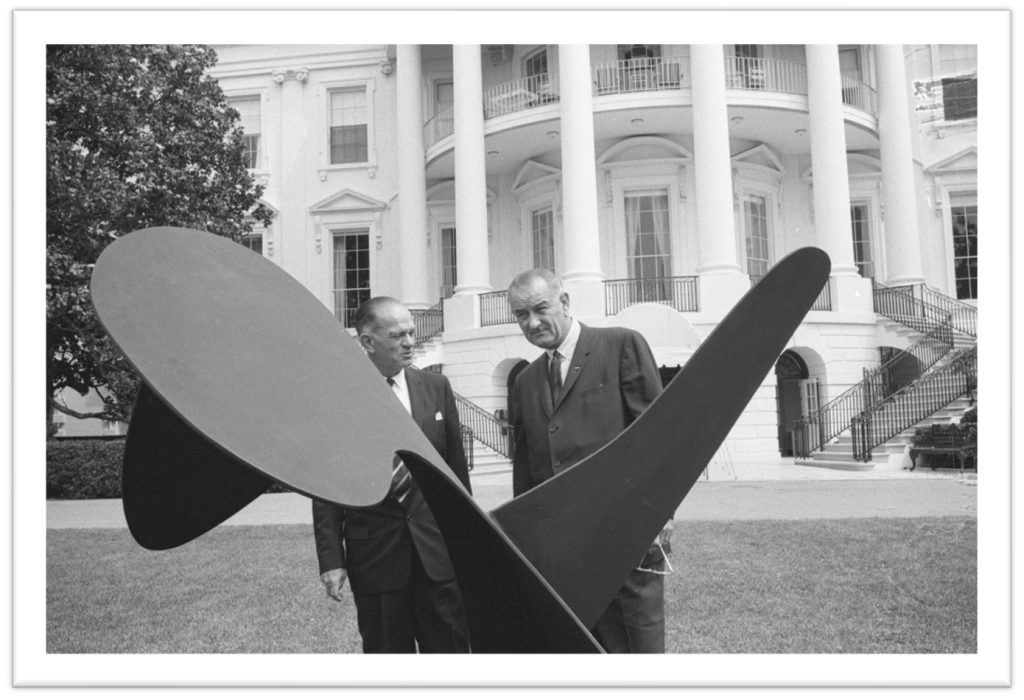

Photos above: President Lyndon Baines Johnson (on right in both photos) with Senator William Fulbright at the White House Festival of the Arts.

Photo by Yoichi Okamoto, White House Photo Office Collection, 1965-06-14-a632, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas.

Above: White House Festival of the Arts Attendees

White House Photo Office Collection, 1965-06-14-34593, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas.

Goldman was the lead organizer of the Festival, and as plans for the event took shape, he wrote to Hersey on May 28, 1965 with details for the prose and poetry section of the program. He requested a reading of approximately ten minutes in length, stating: “We would be happy to have you make this one or more selections from your published writings, or from something unpublished—just as you wish” (Goldman to Hersey 1965). Although some in the White House might have expected Hersey to read from his literary fiction, Goldman’s invitation had left the decision of what to read up to Hersey himself. Goldman only asked Hersey to indicate as soon as possible what he would read. In response, Hersey wrote back to Goldman on June 5, 1965 with two passages from Hiroshima and another from his preface to a reprint of Hiroshima that had recently appeared in a collection of his writings titled Here to Stay (1963) (Hersey to Goldman 1965).

Hersey would elsewhere indicate that he chose the excerpts as an act of protest. He said that he objected to Johnson’s escalations of the war in Vietnam, and that in response, he wished to read to the President a record of American attacks on civilian populations abroad that made the consequences of American foreign policy visible to the White House:

Like many others, I have been deeply troubled by the drift toward reliance on military solutions in our foreign policy….It has been my intention to attend the festival [White House Festival of the Arts] because I felt that rather than by declining or withdrawing, I could make a stronger point by standing in the White House, I would hope in the presence of the President, and reading from a work of mine entitled Hiroshima (quoted in Goldman 1969, 449).

As Hersey makes clear, then, his intention was to confront the President personally at the Festival of the Arts, face to face.

Goldman showed the excerpts Hersey had chosen to Lady Bird ahead of the Festival. She objected to them, stating to Goldman: “The President and I do not want this man [Hersey] to come here and read this” (quoted in Goldman 1969, 457). Goldman recalled that “Mrs. Johnson made it explicit that she was speaking for her husband [President Johnson]” in requesting that Goldman intervene against Hersey (Goldman 1969, 456). At one point in their conversation, Lady Bird read aloud a portion of one of Hersey’s chosen excerpts in which Hersey mentions President Harry Truman, under whose command the United States had dropped the atomic bomb on Japan. Lady Bird frowned at how Hersey associated the Presidency with the ravages of nuclear war. “The President is very close to President Truman,” Lady Bird said to Goldman. “He can’t have people coming to the White House and talking about President Truman’s brandishing atomic bombs” (quoted in Goldman 1969, 456). Lady Bird insisted to Goldman that he prevent Hersey from reading Hiroshima in the White House altogether: “The President is being criticized as a bloody warmonger. He can’t have writers coming here and denouncing him, in his own house, as a man who wants to use nuclear bombs” (quoted in Goldman 1969, 456).

Lady Bird was not the only one who questioned whether the White House Festival of the Arts should become an open forum for debating contemporary foreign policy. Goldman recalls that Bess Abell, White House social secretary, said of Hersey’s plans: “It’s all disgusting. What right does some writer have to tell the President to come and listen to him so that he can make headlines denouncing the President’s foreign policy?” (quoted in Goldman 1969, 456). In her own account of the White House Festival of the Arts, Abell was harshly critical of Goldman, calling him “a real bad egg in the whole thing,” and saying that the problems for the White House that came from the protesters “didn’t have to come. The problems were basically created by Eric Goldman” because some of the invitees that Goldman included on the guest list—such as Lowell—were likely to protest Johnson all along, Abell believed (Oral history transcript, Abell, 16). Abell stated that she “wanted to do something that would be a plus for the Johnsons and a plus for the arts. I didn’t see any need in giving a forum to people who were going to embarrass the President” (Oral history transcript, Abell, 17). In response, Goldman countered that Hersey was a celebrated writer who was entitled to speak as he pleased.

Goldman explained that Hersey’s point was not to attack American Presidents, neither Truman nor Johnson; instead, his point was to take up “the great moral problem of our age—nuclear war,” as Goldman put it. “He is doing it in a context which expresses his opinion that the Vietnam War, utterly contrary to President Johnson’s wishes, might turn into a nuclear war” (Goldman 1969, 456). Hersey’s fear that American involvement in Vietnam could culminate in the use of a nuclear weapon echoed Lowell’s warning in his letter to Johnson that “we…may even be drifting on our way to the last nuclear ruin” (Lowell to Johnson, May 30, 1965). These writers’ statements anticipated the question of using nuclear weapons in Vietnam that military leaders would later pose to the White House themselves as the war wore on. Presidential historian Michael Beschloss notes that around the time of the battle of Khe Sanh in 1968, General William Westmoreland and others secretly considered the use of nuclear weapons in Vietnam in what was code-named “Operation Fracture Jaw” (Beschloss 2018, 555). Westmoreland apparently hoped to position nuclear weapons in South Vietnam, where they could be used on short notice. Johnson strongly opposed the idea of using nuclear weapons in Vietnam, however, and Fracture Jaw was quickly abandoned. Beschloss said in an interview with the New York Times that while Johnson made serious mistakes in Vietnam, “we have to thank him for making sure that there was no chance in early 1968 of that tragic conflict going nuclear” (quoted in Sanger 2018).

Hersey’s reading from Hiroshima at the White House Festival of the Arts had already implied the volatile question of whether nuclear weapons would be used in Vietnam nearly three years before Fracture Jaw. And while Johnson could angrily overrule his General when Westmoreland posed the question in 1968, it was a more delicate matter for Festival organizers to decide how to respond to Hersey in 1965. For whereas the President is commander-in-chief of the armed forces, he wields no such authority over the unarmed forces of the arts. It followed that as White House staff debated what it meant for Hersey to read Hiroshima at the Festival, they inadvertently entered into a deeper dialogue about the principles of freedom of expression in general—the very principles that Johnson said must never be abridged by government intervention, and that the Festival of the Arts was supposed to celebrate.

As these debates unfolded, the question of Hersey’s legal right to freedom of speech was never what was in doubt. The real questions revolved around the more ambiguous obligations of the White House to engage in civil discourse with its own critics by granting writers, artists, and intellectuals the freedom to speak as they pleased, however disagreeable their speech might be for the President. Several related questions cascaded from this fundamental controversy. Was Hersey a White House guest obliged to conduct himself with polite deference to the President? Or was the President, as the leader of the free world, obliged to listen to Hersey speak as he pleased when the writer came to the White House at the President’s invitation? Was the Festival of the Arts a White House event where Washington protocol obliged artists to restrain themselves in the name of social decorum and civility? Or was it an art exhibition convened at a time of crisis that obliged the writer and the artist, as the conscience of a democratic society, to speak out? As these questions collided with one another in White House discussions, they revealed how the practices of cultural liberalism can divide opinion even among those who agree on its premises.

In the end, Goldman frankly stated to Lady Bird and others that to ask Hersey not to read from Hiroshima “would be White House censorship” (Goldman 1969, 458). Yet, even while he made his position plain to others, Goldman harbored doubts of his own. “Was I playing the Boy Scout liberal, indulging my own kind of self-righteousness, lecturing people about principle, insisting on a situation that upset a President with grave problems on his desk?” he wondered to himself (Goldman 1969, 458). Goldman acknowledged that Hersey’s reading at the event would be embarrassing for the President. “Many intellectuals and artists keep throwing Kennedy in his [Johnson’s] face, keep calling him a Texas ignoramus,” he noted, adding that this was all the more painful for the President because the Festival had not been Johnson’s idea in the first place (Goldman 1969, 459). But the President would have to bear the burden, Goldman concluded, because what was at stake was nothing less than the liberal principle of freedom of speech and creative expression that the event itself was designed to celebrate.

Goldman recalled his thinking at the time as follows:

It all seems to him [Johnson] a concerted effort to harass him and to demean him and to embarrass his war leadership. But these were not Hersey’s motives. There are many different worlds of the arts and he comes from the great tradition—the tradition of humanity. He represents the kind of liberalism which has created the environment that makes the President’s domestic success possible. He is not against Lyndon Johnson the human being; he is not against any human being. He is simply worried about Lyndon Johnson’s foreign policy. Don’t let the President put himself in the position of appearing to conform to his enemies’ picture of him. Let Hersey read from Hiroshima (Goldman 1969, 459).

Goldman said all of this and more to the First Lady. But her opinion never changed. He informed the First Lady that he simply could not do as she wished and call Hersey requesting that the novelist change his plans. In the end, Hersey spoke as he pleased at the White House on the day of the event, with Lady Bird in the front row of the audience before him.

Matters of Principle

Goldman’s dialogue with Lady Bird and others in the White House about Hersey’s reading of Hiroshima revealed how the tensions that developed in the run up to the Festival of the Arts tested the White House’s commitment to the very creative freedoms of writers, artists, and intellectuals that were supposed to be protected by the ostensibly inarguable principles of cultural liberalism in the free world. In remarks delivered on the evening of the Festival, in fact, Johnson himself stated in a brief speech on the South Lawn of the White House that one of the most important things the government can do to support artists is to “leave the artist alone” on the understanding that the creative mind “flourishes most abundantly when it is fully free—when the artist can speak as he wishes and describe the world as he sees it without any official direction” (Johnson 1965, 1). As Johnson lauded the artist’s creative autonomy, he also acknowledged that art in the free world is inherently political. “Your art is not a political weapon,” he said to the distinguished group of artists who attended the Festival. “Yet much of what you do is profoundly political. For you seek out the common pleasures and visions, the terrors and the cruelties of man’s day on this planet” (Johnson 1965, 2). However ironically, Johnson’s words describe what Hersey himself was doing at the White House: namely, offering a “profoundly political” statement that examined “the terrors and the cruelties” of the age by reading from a text—Hiroshima—that grappled with what Goldman called “the great moral problem of our age—nuclear war.”

The Stage Where President Johnson Spoke at the White House Festival of the Arts

Photo by Yoichi Okamoto, White House Photo Office Collection, 1965-06-14-a661, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas.

President Johnson Speaks at the White House Festival of the Arts

Photo by Yoichi Okamoto, White House Photo Office Collection, 1965-06-14-a662, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas.

George Kennan’s speech, delivered during a luncheon for attendees at the National Gallery of Art under the title “The Arts and American Society,” also revolved around the meaning of cultural freedom for artists and intellectuals in America. Kennan was an expert on international relations and the Soviet Union who is remembered for responding to the spread of Cold War communism by advocating for a policy of containment. He had little relationship to Johnson himself. In fact, Kennan once wrote that Johnson represented an “oily, folksy, tricky political play-acting” that combined a “self-congratulatory jingoism” with the “whiney, plaintive, provincial drawl and the childish antics of the grown male in modern Texas—this may be the America of the majority of the American people but it’s not my America” (quoted in Gaddis 2011, 590). Although Kennan is rarely associated with the art world, he delivered remarks at the Festival of the Arts because he had just become president of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, in which capacity he addressed the attendees.

Kennan’s speech revolved around what he viewed as the fundamental problem for the arts in a democracy: namely, the gap between the aesthetic imagination as expressed through contemporary art and the workaday concerns of ordinary citizens in society at large who are not artists themselves, and who rarely share—or even understand—the convictions of artists. Kennan said that under these circumstances, the arts speak to American society at large only so long as both artist and public are willing to forge a reciprocal dialogue premised on tolerance and mutual understanding. “Society, for its part, has to recognize and accept the uniqueness of the artist and the eccentricity of his relationship to the rest of us,” Kennan stated. “Society must be prepared for, and must learn to take good-naturedly the unavoidable gap between the level of the artist’s taste and his own” (Kennan 1965a, 3). By the same measure, Kennan reasoned, the artist is obligated to engage the public by articulating the freedom of the aesthetic imagination within the limitations of their craft, their audience, and their own ability. “If the artist wants real freedom in his art,” Kennan stated, “then he must himself define and respect its limitations; for freedom has no meaning except in terms of the restraints that it implies and accepts” (Kennan 1965a, 5). Rebuking self-absorbed indulgence in artistic license, Kennan stated that if an artist “has any sense of devotion to his art as a function of human life…then he must acknowledge a concern for the way it appears to others” (Kennan 1965a, 5). Kennan concluded that “these rules of mutual forbearance” promise to link the realm of art to that of society by forging a reciprocal dialogue in which each side has something to learn from the other (Kennan 1965a, 7).

However paradoxically, though, the White House Festival of the Arts at which Kennan made these remarks had itself produced a level of acrimony that made clear just how difficult it can be to forge a dialogue through the reciprocal obligations of “forbearance” that Kennan described. The irony of the situation was not lost on him, and in fact, he had planned to explicitly address the controversies surrounding the event in a brief addendum to his prepared remarks. These comments were cut from his presentation, however, with Kennan blaming the omission on time constraints, and the historian John Lewis Gaddis writing that Goldman asked Kennan to avoid controversial material in deference to Johnson’s wishes (Gaddis 2011, 591). Whatever the case, the archival records of the Festival preserve Kennan’s perspective on what he called “the question of the relation of the artistic and literary conscience to problems of public policy,” with his basic contention being “merely [to ask] people on both sides to bear in mind the position and the problems of the other” (Kennan 1965b).

In the remarks he omitted from his public presentation, Kennan turns to “one other requirement of forbearance which I should like to mention before I close,” a “requirement” that “relates particularly to what one might call our present national agony over foreign policy” (Kennan 1965b, 1). After making clear that he spoke “with diffidence” and insisting that he did not wish “to aggravate feelings that are already tense,” Kennan had planned to say:

The worker in the vineyard of the arts has, God knows, no obligation to agree with the government in matters of political policy, or to conceal his disagreement. But he will do well to bear in mind that government is made up, in overwhelming majority, of honorable and well-meaning people, charged with preserving the intactness of our national life, without which it is hard to picture any national culture at all; that the problems they meet in this task can sometimes be scarcely less complex and hard for the outsider to understand than those the artist encounters in his art; and that for this reason they deserve at least some measure of that forbearance and benefit of the doubt which the artist is never slow to claim for his own creative work (Kennan 1965b, 1).

Although these remarks were never given, Kennan apparently planned to elaborate that in the same spirit of tolerance, those in government should respect the freedom of expression granted to artists:

They [people in government] will have to bear in mind, first of all, that in the moral spirit of this country, of which the arts are one of the great interpreters and custodians, we have a very special and precious thing—the very soul of the nation, in the sense that to gain the whole world would be profitless in the Biblical sense, if it meant the loss of it; secondly, that artists and writers feel themselves today—more, I think, than ever before, a responsible part of the public conscience of the nation, and are recognized in this capacity by many others, particularly among the youth; and finally, this being so, and for their own sakes as well, that there is a reason to view with concern the anguish many of them feel over these problems, and to respect their need and their longing to be permitted to identify with the methods and the tone of American diplomacy (no less) than with its objectives (Kennan 1965b, 2).

Kennan’s statement on “our present national agony over foreign policy” would seem to have been a necessary meditation on the trouble that had arisen with the Festival of the Arts. But its very omission reminds us that the Festival tested the liberal ideal of reciprocal dialogue between artist and government rather than perfectly embodying it. Ironically, then, the Festival revealed the fragility of the very “forbearance” that Kennan himself believed to be a “requirement” for civil discourse among artists, society, and government in a democracy.

Hersey at the White House

The fragile dialogue between government and artist came closest to its breaking point at the Festival of the Arts when Hersey read from Hiroshima against the wishes of the First Family. Hersey appeared in the “Prose and Poetry” section of the program, which was introduced by Mark Van Doren and featured readings by Bellow, Catherine Drinker Bowen, Hersey, and Phyllis McGinley. In remarks that opened the panel, Van Doren noted Lowell’s protest explicitly, stating “I have been troubled as to whether I should speak of it [Lowell’s protest] at all; I do so now, after several previous attempts, merely as honoring the scruple of a fine poet who, in his own terms, was ‘conscience-bound’ to stay away” (Van Doren 1965). When Hersey’s turn to address the audience arrived, he explained his purpose in reading Hiroshima in the White House by noting that the experience of nuclear war against Japan only twenty years earlier carried lessons for the Cold War world of the Sixties writ large:

Let these words be a reminder. The step from one degree of violence to the next is imperceptibly taken, and cannot easily be taken back. The end point of these little steps is horror and oblivion. We cannot for a moment forget the truly terminal danger in these times, of miscalculation, of arrogance, of accident, of reliance not on moral strength but on mere military power. Wars have a way of getting out of hand (quoted in Taubman 1965, 48).

Looking back, the last line of this statement—“wars have a way of getting out of hand”—feels prophetic in the context of Vietnam. It appears to have changed no minds on the day of the event, however. Lady Bird would later write in her diary that she disapproved of Hersey’s “lecturing,” and contrary to Hersey’s own wishes to address Johnson personally, the President was absent from his reading altogether, as he was for most of the day’s events (Lady Bird Johnson 1965, 1). The President’s diary for June 14, 1965—the day of the Festival—indicates that his only contact with the event came at 10:50 a.m., when he viewed the American Art display with Senator William Fulbright, and at 8:00 p.m., when he delivered remarks on the South Grounds of the White House (President’s Daily Diary, 6/14/65).

The first excerpt Hersey read from Hiroshima describes the experience of Sasaki Toshiko on the day of the bombing:

Just as she turned her head away from the windows, the room was filled with a blinding light. She was paralyzed by fear, fixed still in her chair for a long moment…Everything fell, and Miss Sasaki lost consciousness. The ceiling dropped suddenly and the wooden floor above collapsed in splinters and the people up there came down and the roof above them gave way; but principally and first of all, the bookcases right behind her swooped forward and the contents threw her down, with her left leg horribly twisted and breaking underneath her. There, in the tin factory, in the first moment of the atomic age, a human being was being crushed by books (Hersey 1965, 1).

This quotation appears at the end of the first chapter of the published version of Hiroshima. It exemplifies Hersey’s attempt throughout the volume to narrate the seemingly incalculable implications of the atomic age through the particular experience of an otherwise unremarkable individual. Rather than only viewing the bombing of Hiroshima as an act of war, he views it as an act of—and on—humanity by describing Sasaki as a “human being” who was “being crushed by books” in “the first moment of the atomic age.”

In comparing this excerpt to others from Hiroshima that Hersey could have presented at the Festival, it appears that he set aside some of the most pointed passages with which he might have protested Johnson’s White House. Elsewhere in Hiroshima, for example, Hersey describes in unadorned prose the scientific measurements of the atomic blast, noting that scientists in Hiroshima “found that mica, of which the melting point is 900 degrees C., had fused on granite gravestones three hundred and eighty yards from the center; that telephone poles of Cryptomeria japonica, whose carbonization temperature is 240 degrees C., had been charred at forty-four hundred yards from the center; and that the surface of gray tiles of the type used in Hiroshima, whose melting point is 1,300 degrees C., had dissolved at six hundred yards….They concluded that the bomb’s heat on the ground at the center must have been 6,000 degrees C” (Hersey 1989, 81–82). In another portion of Hiroshima, Hersey explicitly engages ethical questions, noting that while “a surprising number of the people of Hiroshima remained more or less indifferent about the ethics of using the bomb,” it was also true that “many citizens of Hiroshima, however, continued to feel hatred for Americans which nothing could possibly erase. ‘I see,’ Dr. Sasaki once said, ‘that they are holding a trial for [Japanese] war criminals in Tokyo just now. I think they ought to try the [American] men who decided to use the bomb and they should hang them all’” (Hersey 1989, 89). At the White House Festival of the Arts, describing the scientific effects of the bomb and the moral culpability of those who used it might well have made Hersey’s critique of Johnson’s escalation of American involvement in Vietnam all the more polemical.

By the same measure, though, the pointed implications of these passages would have come at the cost of the subtler and more haunting prose that Hersey did indeed decide to read at the Festival of the Arts. In the second excerpt Hersey read, he described “the ruins of Hiroshima” as seen through the eyes of Sasaki Toshiko—the “human being” “crushed by books”—about a month after the bombing. The most striking aspect of the sight is the new vegetation growing in the city, which “horrified and amazed her”:

Over everything—up through the wreckage of the city, in gutters, along the riverbanks, tangled among tiles and tin roofing, climbing on charred tree trunks—was a blanket of fresh, vivid, lush, optimistic green, the verdancy rose even from the foundations of ruined houses. Weeds already hid the ashes, and wild flowers were in bloom among the city’s bones. The bomb had not only left the underground organs of the plants intact; it had simulated them (Hersey 1965, 2).

The regrowth of organic material atop the ashes of Hiroshima conveys the haunting persistence of botanical life in the aftermath of nuclear war. The third excerpt that Hersey shared contrasted with this image by turning to the increasing potency of nuclear weapons from 1945 to 1965. Taken from the preface to a reprint of Hiroshima in Here to Stay, Hersey’s final reading ended with the grim prediction that if the latest nuclear weapon were to be detonated above the western United States, “it would create a fire storm that would render six entire states—Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Nevada, Utah, and Colorado—incapable of supporting life of any kind” (Hersey 1965, 4).

As expected, Hersey’s reading upset the First Family. Livingston Biddle—who wrote the legislation that created the National Endowment for the Arts—said in an oral history of the Johnson White House that “the White House Festival of the Arts cast—certainly over the President—a feeling that maybe this [the cultural community of writers and artists] was not the best constituency to cultivate,” noting that Hersey’s reading of Hiroshima had been difficult for the Lady Bird in particular: “The trouble was that John Hersey, when he read his Hiroshima, did so with Mrs. Johnson sitting in the front row, and her face was just perfectly composed but so stern, listening to that, and she got up immediately and walked very elegantly out of the room” (Oral history transcript, Biddle, 14).2 Biddle summed up that “the White House Festival, I think Lyndon Johnson felt, had insulted his wife, and that was a very bad thing to have happened because he felt very loyal to her and to her stature” (Oral history transcript, Biddle, 15). In her diary, Lady Bird expressed her sadness at how the event had unfolded. She noted “the disasters of the Arts Festival” in general, and lamented “poor Dr. Goldman. He has worked so hard—he did so much—he achieved such a lot. And yet the total result must have been a towering headache, if not heartbreak” (Lady Bird Johnson 1965, 1, 3).

In his own account of Hersey’s reading, Goldman remembered that “The First Lady, who clapped for all other readings, sat motionless” (Goldman 1969, 469). Having labored to orchestrate Hersey’s participation despite the First Family’s objections, Goldman acknowledged that the event had not produced the meaningful dialogue that he originally hoped it would. He wrote that Johnson “needed all the help he could get, particularly from the country’s better educated citizenry. He needed this help especially in the form of criticism and urgings for restraint, the kind that would have come to him if he had looked into the face of John Hersey when he spoke his haunting statement that wars have a way of getting out of hand” (Goldman 1969, 475). Abell—who disagreed with Goldman about much of how the Festival was organized—agreed with him on this point:

I did wish that the President had come to the Arts Festival and had given that day to it and had talked with these people informally; that he had walked around with John Hersey and talked with him informally. I do think that the President really made a mistake of shutting himself off from these people. I think that even if they didn’t sell him on their point of view, that he could have given them an understanding of his problems that would have stayed with them longer (Oral history transcript, Abell, 17).

Goldman and Abell both imply that Hersey’s reading of Hiroshima laid bare one of the unhappy legacies of the Festival of the Arts: namely, that the ideal of “forbearance” that Kennan believed to be a “requirement” for artists to communicate with non-artists in a democracy was ironically what was sometimes missing from an event that was meant to embody it.

Conclusion

Several days after the White House Festival of the Arts, Goldman wrote in a letter to the journalist Peter Lisagor of the Chicago Daily News that “the whole business [of the Festival] was a nightmare for me” (Goldman to Lisagor 1965). Even so, Goldman thanked Lisagor for his balanced reporting on the event. In a journalistic account of the Festival that ran in the Chicago Daily News on June 15,1965 under the headline “Johnsons and the Arts: A Confrontation,” Lisagor contrasted two forms of protest that happened at the event: Macdonald’s circulation of a petition criticizing the President and Hersey’s reading from Hiroshima. He wrote that whereas Macdonald was “openly obnoxious,” Hersey’s statement was a “quiet but powerful warning,” adding that Hersey had acted with “far more dignity and taste” than Macdonald (Lisagor 1965). As Lisagor contextualized these different acts of protest in relation to the broader dynamics of the event, moreover, he indicated that they amounted to no more than one small part of the Festival as a whole. Lisagor wrote that “it would be a distortion of both the spirit and the substance of the occasion to suggest that Hersey’s sincere demurrer either jolted or dominated the event” (Lisagor 1965).

This reminds us that for all that the Festival of the Arts tested and even failed some of its own ideals, it upheld others in the end. Hersey earned the ire of the First Family with his reading, of course, but Lady Bird and the President did not prevent him from speaking altogether. Rothko signed a letter protesting Johnson in public, but even after he did so, Festival organizers proceeded with the original plan to display one of his paintings. The White House hoped to avoid the impression of censoring a dissenter, and, as Goldman put it in a memo to the President, to publicly affirm that “the Arts Festival has nothing to do with foreign or domestic policy and the paintings were picked, after consultation with appropriate art authorities, as being worthy of inclusion on the grounds of sheer painting quality” (Goldman memo to the President 1965). For all that the event is remembered for the protest and acrimony that it generated, finally, the overwhelming majority of participants were happy to accept the White House’s support of the arts.

On the other hand, though, the controversies surrounding the event revealed that cultural liberalism and its promise of free expression can be more controversial in practice than it is in theory, even among those who affirm its premises in public and think of themselves as champions of its cause. By bringing these challenges to light, Hersey’s reading of Hiroshima at the White House during Vietnam bore witness to a nation not only a war with communist enemies abroad, but caught in the paradoxes and ironies of its own notion of “freedom” at home. Hersey’s act of conscience is therefore revealing not only for the way that it intentionally linked Hiroshima to Vietnam, America to Asia, and culture to politics. It is also meaningful for its unintentional effects, the most notable of which was prompting a discussion of cultural freedom among prominent figures who might have otherwise assumed it to have been the uncomplicated and inarguable virtue of the Cold War “free world.”

Works Cited

Beschloss, Michael. 2018. Presidents of War. New York: Crown.

Davis, Kenneth C. 1984. Two-Bit Culture: The Paperbacking of America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Gaddis, John Lewis. 2011. George F. Kennan: An American Life. New York: Penguin Books.

Goldman, Eric F. 1969. The Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Incorporated.

Hersey, John. 1989. Hiroshima. New York: Vintage Books.

Hersey, John. 1965. “Readings of Poetry and Prose, White House Festival of the Arts,” held in the Library of Congress, Washington D.C., Eric F. Goldman Papers, box 65, folder 9.

Johnson, Lady Bird. 1965. Audio diary and annotated transcript, 6/15/1965 (Tuesday), Lady Bird Johnson’s White House Diary Collection, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, accessed online at: https://www.discoverlbj.org/item/ctjd-19650615/

Johnson, Lyndon Baines. 1965. “Remarks of the President at the White House Festival of the Arts (The South Lawn),” held in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas, White House Social Files 1963-1969, Social Entertainment, 6/14/65, box 54, folder labeled “6-14-65: Festival of the Arts at 10:00 a.m & 7:00 p.m. [1 of 2].”

Kennan, George. 1965a. “Remarks by the Honorable George. F Kennan, White House Festival of the Arts Luncheon—National Gallery of Art: The Arts and American Society,” held in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas, White House Social Files, 1963-1969, Social Entertainment, box 54, folder labeled “6-14-65: Festival of the Arts at 10:00am & 7:00 p.m. [2 of 2].”

Kennan, George. 1965b. “Statement of George F. Kennan, June 14, 1965,” held in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas, White House Social Files 1963-1969, Liz Carpenter’s Files, box 16, folder labeled “White House Festival of the Arts: June 14, 165 [2 of 2].”

Larson, Gary O. 1983. The Reluctant Patron: The United States Government and the Arts, 1943-1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lawrence, Mark Atwood. 2008. The Vietnam War: A Concise International History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lisagor, Peter. 1965. “Johnsons and the Arts: A Confrontation.” Chicago Daily News (June 15): 41.

Macdonald, Dwight. 1993. “A Day at the White House.” In The First Anthology: 30 Years of The New York Review of Books, edited by Robert B. Silvers, et. al.: 3-15. New York: New York Review of Books.

Oral history transcript, Bess Abell, interview 3 (III), 7/1/1969, by T.H. Baker, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library Oral Histories, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, accessed online at: https://www.discoverlbj.org/item/oh-abellb-19690701-3-84-30

Oral history transcript, Livingston Biddle, interview 1 (I), 3/20/1989, by Louann Temple, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library Oral Histories, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, accessed online at: https://www.discoverlbj.org/item/oh-biddlel-19890320-1-06-24

Oral history transcript, Edwin O. Reischauer, interview 1 (I), 4/8/1969, by Paige E. Mulhollan, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library Oral Histories, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, accessed online at: https://www.discoverlbj.org/item/oh-reischauere-19690408-1-76-16

President’s Daily Diary entry, 6/14/1965, President’s Daily Diary Collection, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, accessed online at: https://www.discoverlbj.org/item/pdd-19650614/

Sanger, David E. 2018. “U.S. General Considered Nuclear Response in Vietnam War, Cables Show.” New York Times (October 6), accessed online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/06/world/asia/vietnam-war-nuclear-weapons.html

Stout, David. 2002. “Livingston Biddle Jr., 83, Ex-Chairman of Arts Endowment.” New York Times (May 4), accessed online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2002/05/04/us/livingston-biddle-jr-83-ex-chairman-of-arts-endowment.html

Taubman, Howard. 1965. “White House Salutes Culture in America: Dissent of Artists on Foreign Policy Stirs 400 at All-Day Fete.” New York Times (June 15): 1, 48.

Program for The White House Festival of the Arts, June 14, 1965, held in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas, White House Social Files, 1963-1969: Social Entertainment, box 54, folder labeled “6-14-65: Festival of the Arts at 10 a.m. & 7:00 p.m. [1 of 2].”

Van Doren, Mark. 1965. “Reading of Poetry and Prose, The White House Festival of the Arts, June 14, 1965,” held in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, White House Social Files, Liz Carpenter’s Files, box 16, file labeled “White House Festival of the Arts, June 14, 1965 [2 of 2].”

Archived correspondence held in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas. Listed in order of appearance in essay:

Robert Lowell to President Lyndon B. Johnson, May 30, 1965, Gen AR box 2, folder labeled “AR/MC 11/23/63-6/4/65.”

Hannah Arendt, et al., to President Johnson, received June 5, 1965, Gen AR box 2, folder labeled “AR/MC 11/23/63-6/11/65.”

John Hersey to Eric Goldman, June 5, 1965, with enclosures, Gen AR box 2, folder labeled “AR/MC: 6/5/65-6/12/65.”

Archived correspondence held in the Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Listed in order of appearance in essay:

Eric Goldman to John Hersey, May 28, 1965, Eric F. Goldman Papers, box 68, folder 1.

Eric Goldman to Peter Lisagor, June 22, 1965, Eric F. Goldman Papers, box 68, folder 9.

Eric Goldman memorandum for the President [Lyndon Johnson], June 4, 1965, Eric F. Goldman Papers, box 68, folder 1.

Notes

- For a history of the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act of 1965, see Larson 1983: 181-218. Also see “How the NEH Got Its Start”: https://www.neh.gov/about/history

- On Biddle’s role in the creation of the National Endowment for the Arts, see Larson (1983), 201-202, and his New York Times obituary by David Stout, “Livingston Biddle Jr., 83, Ex-Chairman of Arts Endowment,” in the New York Times (May 4, 2002), Section A, Page 11. Accessed online on November 26, 2023, at https://www.nytimes.com/2002/05/04/us/livingston-biddle-jr-83-ex-chairman-of-arts-endowment.html