Abstract: The essay profiles five artists and activists from Cheju Island and narrates their work and commitment to keeping the legacies of the victims of the infamous Cheju 4.3 Incident alive in public discourse. Their activism, embedded in local history and memory, is potentially transnational and archipelagic, inter-referencing and resonating with similar atrocities and related politics of memory and redress in Taiwan’s 2.28 Incident as well as the Battle of Okinawa. Together, each use their own methods and experienced to negotiate and resist nationalist historical revision and capitalist speculation, whose acts erase the voices of the dead.

Keywords: Cheju 4.3 Incident; artists/activism; Cold War; decolonization; personal narratives; the archipelagic

Cheju island: Robert Simmon, using Landsat data provided by the United States Geological Survey. Earth Observatory. From Wikipedia (Public Domain).

At the center of Wimi Village in the southern part of Cheju Island, known as the warmest place on the island, stands an abandoned construction site for an “officetel,” a building that can be used for both commercial and residential purposes. The construction began in 2020, but stopped shortly afterward. Rumors circulate among the villagers that the place is haunted and that the wailing sound of a baby can be heard at night. This construction site has been said to be either a cemetery or a killing ground during the 4.3 Incident, an island-wide massacre that wiped out 10 percent of the island’s population between 1948 and 1954. Driven by the emerging Cold War and ideological rivalry, the state’s punitive forces, dispatched from the Korean mainland, massacred around 25,000 to 30,000 Cheju islanders under the anti-communist banner (Cheju 4.3 Peace Foundation 2019: 366). There is certain evidence to support the rumor of ghosts in the village: the old police station adjacent to the construction site is where twelve residents were slaughtered in the winter of 1948 by police officers at Wimi station (Cheju Special Province and Cheju 4.3 Research Institute 2020: 646-647). The villagers believe that ghosts from the 4.3 massacres haunt this site and endanger the construction workers. One elderly villager recounts that the original owner of this land moved to Cheju city after suffering many misfortunes, including the death of his son. According to this villager, the construction site is cursed and nothing can be done here. Villagers seldom frequent this area. He refuses to say more because too many villagers are involved in the 4.3 Incident, as both victims and victimizers.

This officetel started out as an investment project in which each unit would be sold to individual investors. At first, it tried to recruit Korean investors. Then, in 2010, the governor of Cheju established an immigrant investor visa system, issuing F-2 residential visas to foreigners who invest more than 500 million won in real estate, complete with a permanent resident visa after five years of investment. It unleashed a tsunami of Chinese capital into Cheju Island, with the officetel in Wimi Village one project of many seeking Chinese investors. However, in November 2020, a Chinese construction crane collapsed at the site. The government then issued an order to halt the construction, citing safety concerns (Ko 2020). The construction has stopped indefinitely ever since.

In Wimi Village, ghosts—figures that are neither present nor absent, neither dead nor alive—linger as affective specters and periodic intrusions, and at least temporarily resist being forgotten due to capitalist development. Amid current real-estate speculation, the rumor of ghosts from 4.3 in Wimi captures what the islanders of Cheju currently face: the ineffable and unspoken reminder of the 4.3 massacres buried on empty lots, the capitalist incursions from Chinese investment, and the development boom from mainland Korea that threatens to annihilate their past with new construction. Hotel and office buildings are built on top of massacre sites, but from the perspective of the villagers, these sites are neither abandoned nor undeveloped; they are sites holding local memory that the local villagers know about, but do not speak about. They are labeled “unlucky” places. The landscape of the island is transforming by the day due to endless demolition and construction, but the ghosts continue to hover around the village, refusing to go away.

Spectrality does not beg speculation; it does not matter whether the ghosts are real or not. The fact that ghosts are cited during times of failed development projects demonstrates that development on top of massacre sites is viewed as a bad omen by many villagers. The ghosts represent the social subconscious of the island, one that opposes and interrupts development projects led by external capital that would overwrite the memories of the 4.3 tragedy. Spectrality is an integral part of popular memories of the 4.3 Incident. Anthropologist Kim Seong-Nae observes that the memory of 4.3, which evades the hegemonic memory of the state, remains in fractured and fragmented forms, “surviving in ‘the body of this death,’ a corpse who could speak only in ghostly image and in murky and subliminal spaces such as dreams and possession illnesses” (Kim 2000: 472). The ghosts, seeking to be remembered and demanding justice, are angered by the capitalist forces that would erase them. It raises the question of why we should listen to the specter. The answer is that they signify not just the historical past, but the social subconscious and memory of the Cheju people that exists outside the official archives which constitute the present. As Avery Gordon observed, “the uncanny is the return […] of what the concept of the unconscious represses: the reality of being haunted by worldly contacts” (Gordon 2008: 55). What can be discerned in Wimi Village is the clash of two types of violence: one is the contemporary capitalist violence of development and speculation, and the other is the violence of the 4.3 massacres in 1948. In Korean culture, ghosts are not necessarily evil or hostile beings. They are deceased ancestors who often linger as spirits around the sites of their unjust deaths, hoping to have their han, or deep, internalized feelings of grief and resentment, resolved through the living. In traditional Korean culture, such sites where ghosts reside are referred to as tang. They are protected by villagers and descendants as sacred sites, left empty so the ghosts could be left alone. However, from the perspective of capital, these sites are abandoned and undervalued; no one seems to have wanted them. Capitalism is oblivious and disinterested in the land’s history or the reason for its vacantness. For outside investors and developers, the land only represents opportunities for capitalist accumulation. For local islanders, however, these sites are where their fellow villagers or family members suffered violent deaths. The rumors and spectrality in Wimi are reactions against capitalist seizures of tang and the erasure of colonial violence.

This essay features five profiles of Cheju activists and artists who graciously agreed to meet and speak to us in summer 2019. Subsequent in-person visits were thwarted due to the pandemic, but Lim, who resides in Cheju, was able to communicate with some of the islanders for further comments and clarification. Each islander, although not directly addressing spectrality, attends to the stories of the ghosts from the violent past in their own ways: Park Gyeong Hun is an activist-painter; Heo Young Seon, a poet and director of the 4.3 Research Institute; Hong Chunho, a survivor and voluntary guide for dark tourism; Kang Gwang Bo, a victim of the fabricated espionage charges during the period of military dictatorship, and Yang Bong-Cheon, a member of one of the bereaved families of the 4.3 massacres. Haunted by the ghostly figures of this past violence, these interviewees are akin to translators and shamans, transmitting the voices of ghosts to people living the capitalist present through artistic activism, poetry, sharing personal trauma, and tending the mass grave of massacred ancestors. These islanders are not trying to “resolve” Cheju’s social subconscious or to imagine a closure to the violence and its aftermath. Instead, they demonstrate how the survivors live with the ghosts while embracing their presence and haunting. Collectively, their voices tell the stories of spectral resistance on Cheju Island, the tension between colonial violence and capitalist violence, and the possibility of imagining archipelagic connections between islands with similar Cold War histories, such as Taiwan’s 2.28 Incident and the Battle of Okinawa.

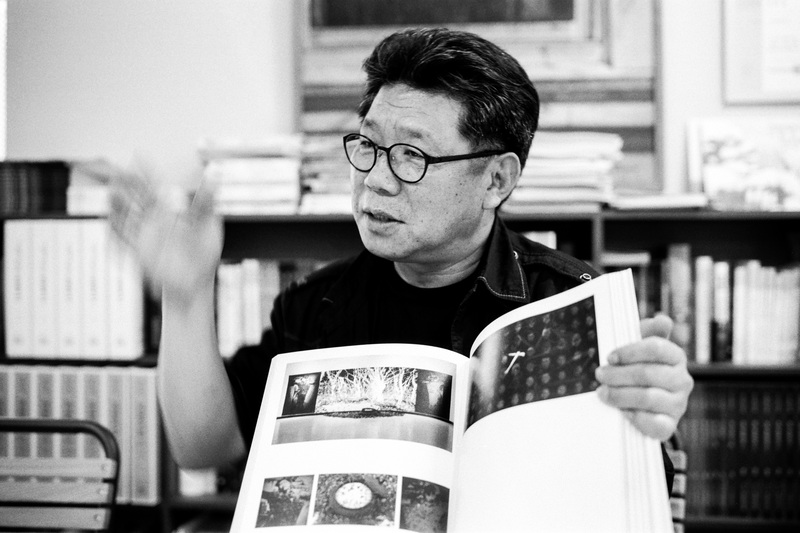

Park Gyeong Hun, painter, former Chief Director of Cheju People’s Artist Federation, representative of the publishing company, “Kak,” which exclusively publishes 4.3 Incident-related materials. Photo: Leo Ching

Since the 1980s, Park has been publicizing and raising awareness of the Cheju 4.3 Incident through woodblock painting, which he works with almost exclusively. Woodblocks are practical for transporting to mobile exhibitions and markets. Park mentions that during the democratization period, woodblocks were a popular form (minjung) of resistance art and he wanted to continue that legacy.1

According to Park, artists were the first to begin the truth-finding effort regarding the 4.3 Incident. In Taiwan’s 2.28 Incident and Okinawa’s war trauma, the media, researchers and bereaved families took the initiatives to call for truth-finding investigations. However, in Cheju, the artists, especially the younger generation, were the first to expose and publicize the atrocity through their writings and paintings. For the older generation who directly experienced the 4.3, the memories were too brutal and traumatic to speak about, not to mention the South Korean state’s suppression of the events. Park recounts that whenever the younger generation of artists tried to talk to the elders about the 4.3 Incident, they would always turn silent or shut them up. For Park and his generation, information on 4.3. came from the Cheju zainichi, Cheju islanders who reside in Japan. One Cheju zainichi, Kim Bong Hyun, was one of the activists who orchestrated the popular demonstration in front of Gwandeokjeong on March 1st, 1947. This event in turn unleashed the shooting incident by the Japanese colonial police, after which Kim fled to Japan. Kim published The History of Militarized Struggle in the 1963 and the Japanese version of the book was smuggled and circulated underground in Cheju and Seoul in the 1980s, prior to the June Revolution in 1987.2 Park notes that through translating the book and using it for self-study on campuses, the students started to grasp a vague but important contour of the 4.3 Incident. The fact that the information about the 4.3 Incident initially came from Cheju diaspora in Japan is not a surprise, given that Osaka and Cheju constituted a single economic bloc and cultural conduit during the Japanese colonial period. Many Cheju intellectuals studied or worked in Japan and later became leaders in student and labor movements.

Students also widely read Lee San-Ha’s poem “Hallasan” to absorb the story of 4.3 from a literary perspective. Soonyi Samchon (1978), a novel by the Cheju writer Hyon Ki Young that discussed the 4.3 Incident, was banned right after its publication, and Park and his colleagues would read it in secrecy. These illicit activities culminated in 1989 when Park and other artists spearheaded an exhibition of paintings on the 4.3 in Seoul, riding the wave of the democratization movement.

Park organized a small painters’ group called “Boromkoji” (in Cheju dialect, it means a corner of the sea cliff where the harsh wind is) made up of 5 to 7 people. There was also the poetry group and the songwriters’ group that discovered 4.3 songs. Recognizing the limitation of working in small groups, they formed the Cheju People’s Artist Federation in the 1990s. The group continues its work to this day and has been hosting an annual festival for thirty years, for which many 4.3 arts are produced.

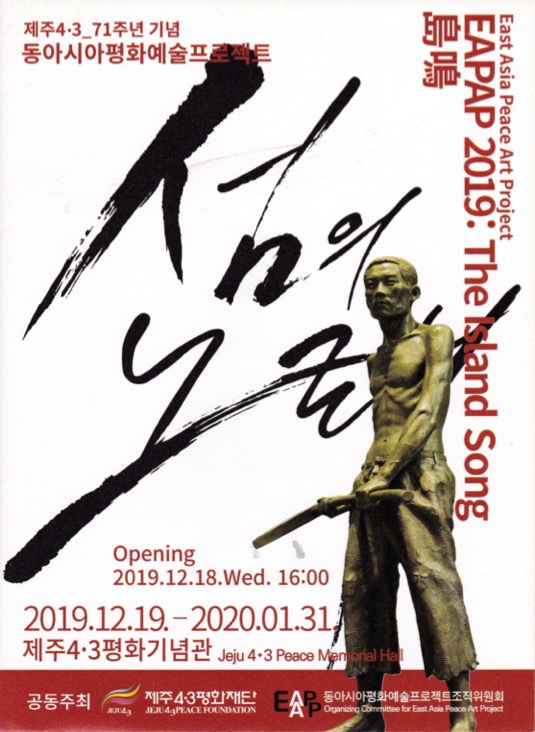

As the leading figure in Cheju’s minjung art scene, Park was the first to suggest and initiate the EAPAP (East Asia Peace Art Project). He has been networking with artists in Okinawa and Taiwan for several years and held the first EAPAP exhibition at Cheju 4.3 Peace Park in December 2019. The idea is to connect Cheju, Okinawa and Taiwan together under the theme of ‘anti-war, anti-base, and peace’ and hold a triennial tour rotating among the three locations. The plan also entails publication of a joint quarterly magazine. The artists do the editing collectively, but each site is responsible for translating and publishing in its own language. Since mainstream media does not pay much attention to these kinds of arts, EAPAP plans to use the magazine as a platform for outreach and publicity.

While the three islands share a common background in that they each suffered from massacres, Park also recognizes their differences. In Okinawa, for example, while there are artists who have dedicated themselves to the anti-base campaign for a long time, there are few who address the paradox of Okinawa’s position as an internal colony of Japan. The Mabuni project at Okinawa Peace Park, similar to Cheju’s 4.3 Art Festival, is just beginning to link American military occupation with Japanese colonialism. Furthermore, in Taiwan, artists have only recently begun to organize. One of the challenges, according to Park, is that artists in Taiwan tend to be individualized and are bound by the gallery system, posing a more difficult situation for organizing. Park has had more success with Okinawan artists in facilitating exchanges between artists for both the Cheju 4.3 Art Festival and the Mabuni exhibition. In discussing peace as the central theme of the EAPAP, Park mentions that “peace can really be discussed by people who actually went through the brutal experience.” Despite different historical and political situations, Okinawa, Cheju, and Taiwan share a similar history of being subjected to state violence as an “internal colony” of their respective mainlands. Moreover, in terms of geopolitics, the three islands are all located on the border line established by the U.S. strategy to make the Pacific its backyard. The artists participating in EAPAP are imagining an inter-island solidarity to fight against this ongoing militarization of East Asia. The EAPAP is an apt example of an East Asian archipelago in the making through island interchange and artistic exchange. EAPAP will continue to seek ways to connect with artists and form an inter-local group across Okinawa-Taiwan-Cheju.

Although the exhibition “East Asia Peace Art Project 2019: The Island Song” took place from December 19, 2019 to January 31, 2020, in the 4.3 Peace Park, further activities have been on hold due to COVID-19. Park certainly recognizes artists from different nations have different priorities and there is difficulty in building momentum. He also admits there are issues of sponsorship and market pressure they must face in order for these exhibitions to be successful. Due to COVID-19 halting the exhibitions, a series of columns began in the Cheju local newspaper Cheju-ui-Sori, titled “East Asia Peace Art Column.” The contributors address discourse on peace in Okinawa, recent trends and messages of peace from Hong Kong, and beyond. The columns are translated into Korean, Japanese, Chinese and English. The goal is to eventually have them published in a magazine format.

Park senses an urgency within this archipelagic coalition. EAPAP, while addressing past atrocities, is a future-oriented project promoting peace. Despite the U.S.-Japan and U.S.-South Korean alliance, the intensifying militarization of the region, in response to the rise of China and along with its hegemonic competition with the U.S., are continually marginalizing if not threatening the islands that exist between them. The question for EAPAP, Park submits, is what art can do amidst the militarization of the islands. If Cheju artists were the ones to lead the truth-finding process, as Park contends, then art can not only reveal the painful histories of the past, but also embody them, investigating and revealing the paradoxes of the present. Art cannot be limited to the exhibition hall, but has to speak to the larger pains and suffering of these regional islanders who are afflicted by state and imperial violence. A particular project aiming in this direction is Park’s outdoor exhibition at the Altre Airfield, which was once used by Japanese imperial army to fly sorties out to bomb Nanjing during the Pacific War. Park has plans to use the remains of the hangers as exhibition sites to draw more visitors and to foster further dialogue.

Official poster for EAPAP 2019.

Heo Young Seon, Director of 4.3 Research Institute and Poet. Photo: Leo Ching

Heo has been serving as the director of 4.3 Research Institute since 2016. The Institute was originally founded in 1989 as a grassroots organization to initiate truth-finding activities on the Cheju 4.3 Incident. It has maintained a close relationship with activists and scholars in Taiwan and Okinawa, considering they share the similar trauma of civilian massacres. There have been many joint conferences and symposiums, and the Institute signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Taiwan’s 228 Memorial Foundation more than twenty years ago. The Institute regularly holds international forums for artists, academics, activists, and others, with notable scholars such as Bruce Cumings and Heonik Kwon having participated.

A former journalist and poet born in Cheju, Heo examines the 4.3 Incident through poetry. She believes that stories and literary imaginations will outlast history and sees poetry as a means to record the names of survivors, each of whose life stories make a narrative poem in itself. For Heo, gender is the beginning and the end of the 4.3 since it was the Cheju women who rebuilt the villages from devastation after the 4.3 Incident. Heo often adds Cheju language to her poetry but does not write solely in Cheju language, as few people outside the island understand the dialect. Since Heo believes that poetry is about arousing sympathy, she makes helping others understand her focus. This issue of translation is especially challenging for many of the other Cheju artists who are trying to publicize the traumatic memory of Cheju to audiences outside Cheju, leading to a dilemma. Must the local dialect always be translated into the standardized language of the mainland in order to be heard and understood? In a sense, this act of translation reflects the hierarchical power dynamic between the island and the mainland, or the difficulties of “decontinentalization,” an epistemological decolonization to shift the geography of knowledge from mainland to island.

Heo’s recent work translated into Japanese, The Sea Women (2017), is organized in two parts: the first, a chronicle of twenty-one women divers Heo met for interviews, and the second poems about these women’s lives and struggles. Heo is keenly aware that her words cannot fully capture the memories, experiences, and suffering of these women, but her hope is that the undercurrents and waves would transcend the national borders between Cheju and Japan. The women divers, known as haenyeo or chamsu in Korean, were compelled to take on the occupation of harvesting abalones, algae, seaweed, octopus, and other sea creatures when men were diverted to other work as the Japanese colonial regime demanded raw materials to make foodstuff and gun powder. The migration of sea women from Cheju to other regions started as early as 15th century, but it was in the late 19th century that the sea women began to travel far and wide in large numbers for the diving labor. Seafood became increasingly commodified in the colonial economy, and Cheju’s inshore fishing ground was quickly devastated by overfishing by Japanese fishing businesses, which were armed with modern fishing technology. Therefore, the movement of sea women during this period was partially voluntary, sparked by economic incentives, but partially forced by exploitative colonialism. Today, due to the declining number of women divers, particularly those who practice their trade traditionally, without oxygen tanks or other modern equipment, the figure of the sea women has become attractive for tourists and medical research. Additionally, these women are idealized for their remarkable resilience. In her book, Heo touches on the danger and mortal consequences surrounding the women divers’ labor and how they must rely on each other and developed strong bonds among themselves. To recapture their political agency, Heo recounts how the women studied with young intellectuals during the colonial period and that their anti-Japan struggle was not merely spontaneous or disorganized. Heo specifically points to the Sehwari market protests of the 1930s. These protests initially gathered three hundred sea women, but they were joined by other women as well as peasants from other districts until their numbers swelled to 17,130. They convened 238 times (Heo 2020: 36), marking the largest anti-Japan struggle in the 1930s and the largest fishermen and women’s struggle in Korean history. On top of the already aggravating colonial exploitation of sea women, the conflict was also borne due to unfair seafood pricing, and exploded in the form of the Sehwari market protests in January 1932 (Chosŏn Ilbo 1932). The colonial authorities sent a police force from the mainland to suppress the movement, and when the colonial authorities began to perceive the struggle as an anticolonial movement, they began arresting young intellectuals in Cheju for abetting the sea women through education. In response, the sea women resisted even more strongly; around 500 sea women attacked a police station in Sehwa village to set the arrested men and women free. As a result, about one hundred women were taken into custody and the leaders were tortured, some by waterboarding (Tong-a ilbo 1932). However, as Kim Ok-Ryun, the leading figure of the protest, recalled later, the sea women adamantly endured the torture: “Let them pour the water/I only have to bear it as long as I dig one abalone from underwater” (Heo 2017: 14).

The first part of Heo’s book is divided into four sections focused on different themes—sea women’s struggles, migration and expropriation, the Cheju 4.3 Invident, and the lives of sea women—and covers twenty-one women divers. The sea women are also migrant workers, diving not only around the waters of Cheju, but also in the sea ways of the Korean Peninsula, China, Russia, and Japan. They are nomadic, matrilineal, and often the sole wage earners in their households. The routes of their journeys form an archipelago: from Cheju to the north, passing several islands, reaching Yondo (near the Busan strait) and further north to Gijang, Ulsan, Dalian, Qingdao, and ending in Vladivostok. To the south, they traveled to Daimado, Gotō, Amakusa, Tosa, Kagoshima, Ehime, Ise-shima, Shizuoka, Miyake-jima, Hachijō-jima, Chiba bōsō, the Shimokita peninsula, and Osaka Chikkō. Their travel was a process of tracing fluid fishing ground. Some sea women who left for Japan settled there, especially in Osaka, instead of returning. Anthropologist An Mi-Jeong observes that the sea women from Cheju and the Japanese ama often formed a mutually cooperative relationship as they shared their knowledge of using specific tools or diving techniques with each other. Beyond the dichotomous boundary between colony and empire, Korea and Japan, there lied a shared life world where they could sympathize with each other as “fishing people who dive underwater for labor” (An 2019: 134).

The second part of the book begins with a Cheju folk song that refers to the mythical island of Iodō which, once reached, one would never be able to leave. The sea women keenly feel the pull of Iodō every time they dive into the water. The song reflects the women’s will to live and their hopes for the future. The communal nature of the sea women lies behind the creation of these folk songs. When the sea women left for the coastal waters around the Korean peninsula and Japan, they did not leave individually, but rather as small groups of women, usually from the same village. As neighbors or relatives from the same hometown, these sea women continued their community life even so far from home, and they sang their native folk songs together to ease their exhaustion from the harsh labor and their homesickness. The songs continue to serve as vocal archives of those working-class women who did not leave behind written records of their lives (An 2019: 88).

Regarding the 4.3. Incident, as Heo told us in the interview, no one on the island has not been affected. Every person is either related to the victims or the victimizers. She laments that those memories are almost never spoken about at home. It is the pain and sadness concealed within each family’s history. Those memories can potentially bring misfortune to those who know of them. Thus, Cheju is an island where memories are murdered. Heo has, as a journalist and poet, tried to excavate the repressed memories with empathy and care, listening to the “frozen voices.” She only begins her own narrative when she reached the point where no further words from others could be spoken—her own voice melts with the memories and voices of those diving women.

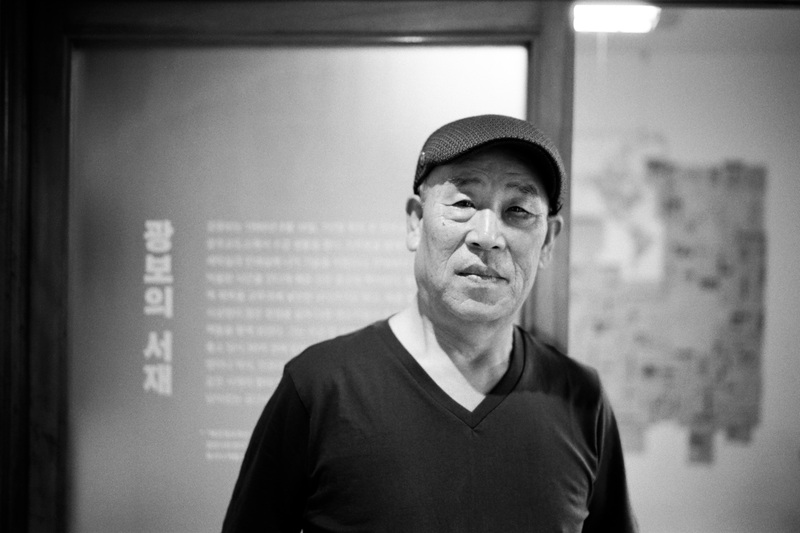

Hong Chunho, 4.3 survivor who volunteers as a guide for dark tours. Photo: Leo Ching

Now over eighty years old, Grandma Hong was eleven at the time of the 4.3 Incident. Hong volunteers as a guide for travelers visiting Mudeungyiwat, the “lost village” that had been burnt down by the punitive forces as part of scorched-earth operation during the 4.3 Incident and left abandoned ever since (Cheju 4.3 Peace Foundation 2019: 124). Visiting historic sites or massacre sites related to 4.3 has become a more popular activity among tourists coming to Cheju. Such trips are usually accompanied by local guides from the 4.3 Research Institute or Cheju Dark Tours, which Grandma Hong often takes part in. In contrast to commercial dark tourism, Cheju Dark Tours was founded in 2017 as a non-profit organization to promote peace and human rights. While dark tours in other parts of Korea are still rare, Cheju Dark Tours has been very active in devising various programs for visitors, such as hosting 4.3 trail tours guided by 4.3 survivors, forming solidarity with victims of state violence overseas including Okinawa and Taiwan, and documenting historic sites related to Cheju 4.3. The activists at Cheju Dark Tours attribute their success to the popularity of Cheju Island as a tourist destination in general, since tourists can easily pay a visit to the 4.3 Peace Park or other related sites as part of their itinerary.

In their pioneering work on dark tourism, John Lennon and Malcolm Foley explain the increased interest in death and disaster as a phenomenon specific to late-twentieth and early twentieth-first century tourism (Lennon and Foley 2020). While visits to battlefields, mass graves, sites of assassinations and other atrocities are not new, Lennon and Foley situate dark tourism within the (post)modern tourist experience, where death becomes a commodity for consumption in a global communications market. More pertinent to the discussion at hand, Lennon and Foley argue that dark tourism serves to introduce “anxiety and doubt about the project of modernity” and the meta-narrative of legitimation such the ‘rational’ planning and execution of Nazi death camps or the use of atomic weapons at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We might also include the 4.3 Incident here, for its part in the calculus of Cold War American anti-communism and postcolonial Korean nation-state building. While recent research on dark tourism (or thanotourism) has focused on supply (industries and management) and demand (interests of tourists), dark tours in Cheju demonstrate how dark tourism can also serve as a means of grass-root activism and addressing the trauma of 4.3 survivors. According to activists at Cheju Dark Tours, when dark tour participants ask the 4.3 survivors volunteering as guides about their happiest moment in their arduous lives they had to endure, the elderly volunteers answer that right now is their happiest moment. After spending their lives feeling as if they themselves were the sinners, the survivors and bereaved families of Cheju 4.3 are suddenly experiencing people seeking them out to ask for their stories. These frequent encounters with the younger generation are helping the survivors to realize that they are not the guilty ones after all. Similarly, Grandma Hong sees her voluntary work as a method to help her to cope with personal trauma, as she gains satisfaction by sharing the hardships Cheju islanders had to endure with the younger generation.

Most of her recollections on the 4.3 take place on oreum. Oreums are small volcanic cones or domes around Hallasan (Mt. Halla), the highest mountain in South Korea. They are well-preserved and highly porous. There are over 360 of them on Cheju, forming a unique island landscape. During the massacres, oreum were used as sanctuaries where people hid away to survive. Hong’s family went into hiding in the Keunneolgwe cave with other villagers who sought refuge from the indiscriminate killings of the 4.3 Incident.

During the interview with Hong, we were struck by the variety of details Hong employed to describe the island’s scenery in her memory. The island’s landscape is inseparable from her memories of struggles for survival during the massacre. Hong would vividly recall how far away and how tall the oreum she had to travel to for water from was, the height of the bamboo in the massacre site in her village, and the tiny size of the cave mouth her family and villagers went in to hide from the state’s punitive forces. The islanders were exploring and rediscovering their island’s landscape in a novel way as part of their search for a refuge. In this manner, the islanders were engaged in their own spatial heuristic of archipelagic thinking. The oreum on the island become what Lanny Thompson calls “geosocial locations,” providing a vantage point from which to produce new knowledge (Thompson 2017: 68).

The use of geological spaces on Cheju Island has its correlative in the gama, or limestone caves on Okinawa. During the war, especially in the later stage of the Battle of Okinawa, the gama were used for refuge, storage, and as outdoor hospitals. They are also sites where compulsory mass suicides took place, either by coercion or directive of the Japanese military.

While nowadays oreums in Cheju are popular hiking destinations, mostly valued for their scenic beauty, since ancient times, the Cheju oreums have been essential for the islanders’ livelihood. The oreum functioned as sites for military defensives and village stock farming, and provided crucial resources like firewood and water. Oreums were village cemeteries, where islanders were buried when they died. Oreums are also inseparable from 4.3 because they were used both as site of refuge for the islanders and guerillas as well as massacre sites by the punitive forces.

The oreum and gama can be considered markers of an archipelago formed among a lateral network of islands due to their similar geophysical formation and creative usage during battles. They are not simply spatial metaphors, but produce “creative transfigurations” of material, cultural, and political practices. This highlights island-island relationships as opposed to the typical center-periphery or mainland-island relationship, lending to a “metamorphosis” of those islands’ relations (Pugh 2013, as cited in Thompson 2017: 63).

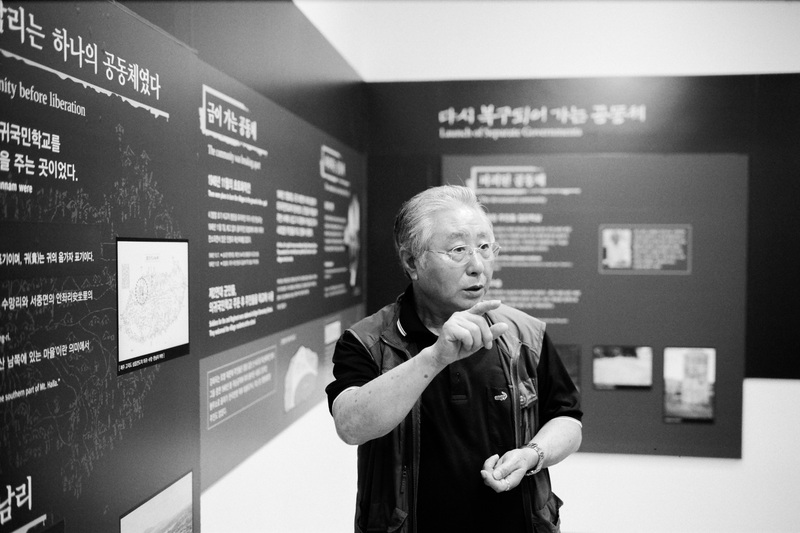

Kang Gwang Bo, Founder of Suspicious House. Photo: Leo Ching

Cheju’s geographical proximity to Japan led many islanders to go to Japan as laborers and students, especially during the Japanese colonial period. Many of them were participating in or had close ties with Chongryon, a group of ethnic Koreans in Japan more closely identify with North Korea, and other leftist organizations. After the 4.3 Incident, Cheju was extremely poor, so many Cheju islanders were smuggled to Japan, often settling in Ikaino, the Korean town in Osaka. Kang was one of them, and he stayed in Ikaino for 18 years, during which he got married and had three children. In 1979, Kang was captured by Japanese immigration officers and deported back to Cheju. Upon his arrival in South Korea, Kang was subsequently arrested, jailed, and tortured on suspicion of being a North Korean sympathizer and spy. After finishing his prison sentence, Kang came back to his parents’ house in Cheju which he rebuilt as the “Suspicious House.” Suspicious House opened in June 2019, and he hopes to use it to hold cultural activities such as book reading sessions, meetings with local villagers, and concerts. Kang wants the meetings to become opportunities to tell everyone that, despite having been stigmatized as a spy, he is not guilty. Ultimately, he wants to share how he resisted unjust state violence.

Cheju people who oscillated between Japan, mainland Korea, and Cheju Island are examples of “diasporic archipelagoes” formulated through migratory movements to and from various forms of geographic places (Thompson 2017: 67-68). As they migrate back and forth, they carry their “islandness” with them. Thus they are not always assimilating, not into Japanese society and not even into Korean mainland society, as Cheju islanders are often conflicted regarding their Korean national identity. At the same time, from the perspective of the state, their fluid identity becomes a source of suspicion and pretext for persecution. While this made Cheju islanders and the zainichi susceptible to exclusion from the boundaries of a nation-state, it also allowed them to creatively forge an archipelagic space without losing their ties to their island. The figure of the Cheju zainichi constitutes what Walter Mignolo has called “the colonial difference,” a different locus of enunciation based on different colonial experiences (Mignolo 2002: 61). Whereas the South Korean government has only begun to earnestly appoint truth-finding committees and commemorate the victims of the 4.3 massacre in the early 2000s, the diaspora community across the strait in Japan has retold the incident “in chant-like, or perhaps curse-like refrains” for over half a century (Ryang 2013: 3). Cheju zainichi’s memories of the 4.3 Incident closely align with the North Korean version, which is anti-U.S. and anti-Rhee regime, and as islanders they were also keenly aware of the broader context of regional prejudices held by mainlanders toward Cheju islanders for centuries (Ryang 2013: 7). In short, the diasporic archipelagoes configured by the Cheju zainichi’s lived experience and cultural trauma constitute a liminal space that is incommensurable with the nationally constructed memory of either the South or the North.

The colonial difference evinced by the Cheju zainichi is clearly and emphatically demonstrated by Koh Sungman’s study of the archivization of deaths in commemoration of the 4.3 Incident, or what he calls the “politics of death” (Koh 2015). Koh examines the works of the 4.3 Committee as one of the transitional justice strategies of the South Korean government, questioning how the dead are selected and reorganized as well as the formalization of the dead through official monument and commemoration with the 4.3 Peace Park. Although more than 80% of the killings were attributed to the suppression of the uprising, the Committee established classification criteria for the victims of the 4.3 Incident based on what the nation considers as having “identity of the Republic of Korea and the basic liberal-democratic order of constitutional spirit” (The 4.3 Committee 2008: 148-150 as cited in Koh 2015: 290). The so-called suppressors, such as soldiers, the police, and right-wing youth organizations, the actual perpetrators of the massacre, and the civilians they killed are all broadly categorized as “4.3 victims.” Those who resisted, such as the armed guerillas who confronted the US military and the South Korean government, and those who held strong leftist ideological convictions of Korea at that time are excluded from victim status. The latter, in the context of the official history of South Korea, are nothing but the “impure dead” who damaged the legitimacy of the nation-state. In short, the committee only screens ‘victims’ and ‘non-victims’ to consecrate the former.

Contrary to the official archivization of the dead by the 4.3 Committee, Koh’s ethnographic analysis of the unofficial ritual ceremonies to console the grief caused by the 4.3 Incident by the Cheju zainichi community in Osaka offers an archipelagic alternative to the moralistic and state-ideological approach of the South Korean government. In one of the annual commemorations in Osaka, Koh observes that after a performance, where a woman reenacts a vain search for her lost husband, papers representing the dead, without names, are scattered on the stage. The dead are referred to simply as “the 4.3 victims’ souls.” The individual dead are not named, and the “souls” are randomly dispersed on stage, reminiscent of the dead bodies scattered at the massacre site. This is in contrast to how victims’ names are displayed in a logical order on official monuments in the Cheju 4.3 Peace Park. The performance on stage elicits spontaneous impromptu participation. What the ceremony rejects is the binary opposition between the ‘victims’ and ‘non-victims’, the dead and the living, and first and later generations of zainichi. Koh writes: “Those actions of trying not to assign moralistic meaning of the memorial service are similar to their own survival strategy as an ethnic minority with an ambiguous position in terms of postwar Japan’s legal status…The Osaka memorial service has a significant meaning because it seeks to create an alternative form of historical memory” (Koh 2015: 298).

What makes the Cheju zainichi’s remembrance possible is their lived experience of traversing the seaway from Cheju to Osaka to seek refuge from oppression by both the South Korean and Japanese governments. Cheju islanders came to consider Osaka and Cheju as the same living sphere since Japanese occupation due to the island’s close physical location vis-a-vis the island nation. Their flight from Cheju due to political suppression and economic destitution and their ambiguous status as resident aliens in Japan allowed them to forge and imagine a radically different relationship to the dead, and by extension, to the living. However, their ambiguous status also put them in vulnerable positions especially under the political climate of anti-communism across the strait.

The stigma of being labeled as “Reds” in post-liberation Korea in addition to the islanders’ close ties with the zainichi community made Cheju people particularly susceptible to being framed as “spies” by the South Korean government. According to a report by the Catholic Human Rights Committee of Korea, nearly 34 percent of those falsely accused as “spies” were from Cheju (Chwa 2022). Cheju island’s proximity to Japan meant islanders have traveled back and forth to Japan throughout history. Especially during the Japanese colonial period and the 4.3 massacres, islanders often smuggled themselves to Japan for better economic opportunities or safety. As a result, Cheju islanders made up the majority of the zainichi population. Multiple ideologies and nationalities coexisted within the zainichi community, though this sometimes led to rivalries between groups, such as that between the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (Chongryon), a pro-North Korea organization, and the Republic of Korean Residents Union in Japan (Mindan), a pro-South Korea group. Some of the islanders who fled Cheju for survival at the outset of the 4.3 massacres refused to choose either South or North Korea as their nationality. However, following the violence, many more joined Chongryon due to their antagonism toward the South Korean government who was responsible for the massacres. This close political connection between the zainichi community and Cheju Island made the islanders easy targets for false espionage charges by the South Korean government. After liberation, zainichi Cheju islanders often sent their hard-earned money back to Cheju to build schools in their home villages. South Korean national security agencies viewed the islanders’ attachment to their hometowns as attempts at spying or infringements of national security, and would consider their donations to be North Korean operational funds (Pyŏn 2020a).

For many islanders in Cheju, the stigma of being labelled a “Red” during and after the 4.3 Incident was passed down from one generation to the next. Concrete evidence of this can be seen in the guilt-by-association system, which punishes or disadvantages the offender’s parents, spouse, children, and siblings for their family member’s crime. Guilt-by-association was abolished in Korea in 1894 during the Kabo Reform, but persisted as a form of colonial surveillance during the Japanese colonial period (The National Committee 2014: 608). Guilt-by-association was frequently imposed during the period of intense ideological rivalry that arose after liberation in 1945 as a social practice to filter out subversives through background checks and surveillance. People subjected to guilt-by-association were often family members of victims of state-led massacres like 4.3, family members of those who defected to North Korea, and people suspected of espionage or violations of the National Security Law. Official abolition of guilt-by-association occurred in 1980, but there were lingering suspicions by the victims that the system unofficially existed even after nominal abolition. One elderly Cheju islander recalled that his visa application for a group tour to China in 2001 was initially denied due to his being recorded as a political offender during the 4.3 Incident (The National Committee 2014: 611).

In Cheju, a majority of survivors and bereaved families of 4.3 have experiences of being subjected to guilt-by-association. According to the government-led Cheju 4.3 Incident Investigation Report, 86 percent of bereaved families answered that they have experienced one or more cases of guilt-by-association (The National Committee 2014: 609). More specifically, these cases include being at a disadvantage in public servant recruitment tests and other entrance exams including those for the Military Academy, while seeking employment and promotion in national, public, or private companies, as well as promotion in the military or the police. It has also affected bereaved families when they travel internationally or try emigrating outside of South Korea, or even just in their daily lives where they feel unfairly surveilled. Cheju islanders who had been falsely accused of espionage also continue to suffer from the guilt-by-association system. One of the victims, Oh Gyeong-dae, decided to apply for a retrial after his son immigrated to Italy in 2016, leaving him a long letter. In the letter, Oh’s son pleaded Oh to understand why he had to leave his old father behind, confessing how his dreams of entering the police academy, becoming a public servant, opening a business of his own were crushed one after another each time Oh’s past was revealed (Pyŏn 2020b). Being an island community that is so tightly knitted together, Cheju people have suffered particularly long and hard from the unjust consequences of guilt-by-association.

Yang Bong-Cheon, Caretaker of Hyeonuihapjangmyo (burial ground and memorial for civilian victims in Uigwi Village). Photo: Leo Ching

Uigwi Village, located in mountainous area south of Mt. Halla, is well-known to have suffered severe destruction during the 4.3. The state punitive forces stationed in Uigwi Elementary School indiscriminately killed and imprisoned many villagers, which led the mountain guerilla forces to launch an attack on the punitive forces. During a series of attacks and counterattacks between December 1948 and January 1949, the punitive forces massacred eighty villagers after accusing them of colluding with the guerillas. The corpses were left in the field to rot for months. Unable to separate the dead bodies, the villagers built a mass burial ground called Hyeonuihapjangmyo, meaning “righteous people are buried together.”

Hyeonuihapjangmyo. Photo: Hyesong Lim

Yang’s father was among the eighty villagers killed in a field next to Uigwi village. Yang can still recount exactly who those eighty victims were and whose family they were from. From an early age, he would go along with village elders to tend the graves. The mass burial ground was excavated in 2003 by villagers to appease their ancestors. Yang participated in this excavation with a professor of forensic medicine at Cheju University, who ran DNA tests to separate out the bones of men, women, and children. Yang himself removed bullets from their bones. Those bullets are now preserved at the 4.3 Peace Park. Yang spoke calmly when he mentioned the bones of children they found during the excavation: while the adults’ bones were hard and remained intact, since the bones of babies are soft, they had already decomposed into a white powder and become part of the soil by the time they were excavated. On the day these powdered bones were discovered, the professor, Yang, and village elders discussed what to do with them. They ended up burying a fistful of powdered bones in the mass grave. Giving a proper burial to the dead and tending their graves carry central importance in Korean culture. Thus, as the interview with Yang revealed, the mass grave does not resolve the han of the bereaved families; rather, it is a source of unappeased grief.

About a mile away from the mass grave for the villagers lies Songryeongyi-gol, a mass grave for the armed guerillas. In contrast to Hyeonuihapjangmyo, this mass grave is a modest mound hidden in the grassy field along a narrow farm road. The bodies of armed guerillas who were killed in conflict with the punitive forces at Uigwi Elementary School in January 1949 were buried en masse at Songryeongyi-gol. It was left untended until 2004, when a group of Buddhist pilgrims, along with the bereaved families at Hyeonuihapjangmyo, set up a small wooden tablet and performed a religious ritual to appease the dead. On the panel, it reads: “All lives should be respected. As the old saying goes, ‘Even when you pass by the grave of your enemy, make a deep bow before you pass.’ […] We consider both the leftists and the rightists as victims of ideological confrontation. Not only the massacred civilians, but the soldiers, the police, and the armed guerillas were all my brothers and my parents, sacrificed in Korea’s ‘liberated space’ and the Korean War.” The presence of both a mass grave for villagers and one for guerillas in Uigwi Village is intriguing when contrasted with the homogenization of the dead “victims” in the official memorials. The mass graves at Uigwi Village and those official memorials at the Peace Park both use the word “victims” to refer to those who died during the 4.3 Incident. However, instead of absenting the armed guerillas or the “impure dead” from the memorial sites altogether, these deceased can coexist alongside the others buried in the mass graves in Uigwi Village. Rather than only awarding certain dead the title of victim, the mass graves in Uigwi Village reveal complex nature of violence and the ambiguous relationship between the killers and the killed.

Songryeongyi-gol. Photo: Hyesong Lim

Also in Namwon-eup in which Uigwi Village is located, Namwon-eup Cemetery for the “loyal dead” was established in 1991. Those buried here were generally members of the state punitive forces—the police, military, public officials, and others who died as members of paramilitary groups—during the 4.3 massacres. One tombstone reads: “died during the cleanup operation of communist guerillas in Mt. Halla.” The cemetery is easily accessible since it is located right by one of the few main roads leading to Mt. Halla. The tombstones are aged but grand, and the more recent ones are a shiny black marbles. A high tower stands in the middle of the cemetery, and the national flag of South Korea flutters on a pole right next to it. The national flag is easily spotted throughout the cemetery; some tombstones have the flag engraved on them, and an artificial chrysanthemum and a miniature flag are neatly placed in front of each tombstone. The national flags in the cemetery serve as markers that the people buried here are officially recognized by the state. There is a clear contrast between this well-tended cemetery and the guerilla graves at Songryeongyi-gol.

Namwon-eup Cemetery for the loyal dead. Photo: Hyesong Lim

The different treatment of each of these mass graves is proof of contentious memory yet to be resolved. As Sungman Koh criticizes, the 4.3 Committee classifies the dead into simply two categories: ‘victims’ made up of the punitive forces and civilians, and ‘non-victims,’ or the armed guerillas (Koh 2015: 293). This dichotomy reinforces the state-centered interpretation of the conflict, in which the armed guerillas with strong leftist ideology threatened the nation-state as the subversive other, killing the state agents and “innocent civilians.” However, the coexistence of the three different mass graves at Namwon-eup (mass graves for state punitive forces, guerillas, and civilians), and the fact that guerilla deaths are remembered and privately commemorated by the bereaved families at Uigwi village reveal that these guerillas were more than simply the “impure dead” as recorded in national history. In local memory, the guerillas were also members of the island community, regardless of their ideological stance. Moreover, the guerillas sometimes tried to save the villagers from the violence of punitive forces dispatched from the mainland, as seen in the history of Uigwi Village. In other words, the victim-assailant dichotomy is not always so clear-cut for the locals.

The locals on Cheju Island are much more tied up with the political dynamics on the mainland. The islanders cannot be completely free from the ideological demand to identify the victims and non-victims. In commemorating the dead and remembering the 4.3 massacres, there exist multiple levels. First, there is the diasporic level represented by the zainichi community: the diaspora does not differentiate victims and victimizers due to their ambivalent or ambiguous status. Second, there is the state/national level, as seen in the 4.3 Peace Park and the cemetery for the loyal dead: the state categorizes and separates the victims and the non-victims, erasing the ‘impure dead’ and making them impossible to grieve. Third, there is the local level, in which the local villagers like Yang are continuously negotiating different levels of victimhood. In this sense, Cheju Island remains as a site of active place-based politics.

Conclusion

As we hope to have shown through these profiles, the struggle over the meaning of the 4.3 Incident continues for local artists and activists. Despite their different ages, backgrounds, and status, they share a commitment to keeping the legacies of the victims of the 4.3 massacres alive. Park’s woodblock paintings and his determination to form the East Asia Peace Art Network, Heo’s poetry and narratives on the legacies of the sea women, Hong’s dark tourism and memories of the oreum, Kang’s experience as a victim of anti-communism and his building of Suspicious House, and Yang’s caretaking and veneration of the dead all weave the past as an integral part of the present. Unlike the rampant capitalist development upon the grounds of the dead, which treat the past as if something that can be erased or wished away by accelerated construction and commercialization, the individuals profiled remain attentive to the voices of the ghosts, who impose an irrecuperable intrusion into our world that is incomprehensible to existing intellectual frameworks, but whose “otherness” we are responsible for preserving. What is presented is an ethical injunction to care for the dead and listen to their ghosts.

Finally, we come to understand “archipelagic imagination” as operating on two levels: one that reframes continentalism, such as the American empire, archipelagically (Stratford 2018). In short, this is a process of decontinentalization and, in the case of Japan and South Korea, de-mainlandization. The task is to free continents and mainlands of their alleged solidity and supposed inviolability. The other views archipelagoes as assemblages or networked interchanges that are both geographical and cultural. Maintaining their particularities and yet connecting their formations beyond their shores, island-island interchanges challenge the perceived insularity of islands as bounded and closed-in (Roberts and Stephens 2018: 30). We evoke the archipelagic instead of transnational to highlight the specific asymmetrical power relationship between islands—particularly Cheju, Taiwan, and Okinawa—to their respective mainlands/continent of South Korea, China, and Japan. While not all the activists and artists profiled here reference Taiwan and Okinawa specifically through the concept of the archipelagic, we believe they offer insights and, more importantly, the potential, to imagine the 4.3. Incident, the 2.28 Incident and the Battle of Okinawa and their aftermaths as a conjoined process brought on by the Cold War and the failure of decolonization in East Asia. As capitalism continues to remake a landscape marked by mass killings through speculation and development, militarism and nationalist chauvinism increasingly threaten the fragile peace of the region. The works and struggles of Park, Heo, Hong, Kang, Yang, and many others provide a glimpse of hope for not only challenging dominant nationalist narratives, but also imagining different ontologies, epistemes, and values.

References

An, Mi-Jeong 안미정. 2019. 한국 잠녀, 해녀의 문화 [Female Divers of Korea, History and Culture of Sea Women]. 서울: 역락 [Seoul: Yŏngnak].

Cheju 4.3 Peace Foundation 제주4.3평화재단. 2019. 제주4.3사건추가진상조사보고서 I. [The Cheju 4.3 Incident Additional Investigation Report I]. 제주: 각 [Cheju: Kak].

Cheju Special Province and Cheju 4.3 Research Institute 제주특별자치도, 제주 4.3 연구소. 2020. 제주4.3유적 [Cheju 4.3 Historical Sites II]. 제주: 각 [Cheju: Kak].

Chosŏn Ilbo. 1932. ‘제주해녀 시위상보 [A Report on Cheju Sea Women’s Demonstration].’ 조선일보 [Chosŏn Ilbo], 24 January.

Chwa Tongch’ŏl 좌동철. 2022. ‘간첩조작사건 피해자 첫 실태조사 착수 [Investigation of. Victims of Espionage Manipulation Begins for the First Time].’ 제주일보 [Cheju Ilbo], 23 January.

Gordon, Avery. 2008. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Heo, Young Seon 허영선. 2017. 해녀들 [Sea Women]. 파주: 문학동네 [P’aju: Munhaktongne].

Heo, Young Seon. 2020. Amatachi [The Sea Women, A Collection of Poems]. Tokyo: Shinsensha.

Hyŏn, Kiyŏng 현기영. 1979. 순이삼촌 [Sunisamch’on]. 서울: 창비 [Seoul: Ch’ang Pi].

Kim Seong-Nae. 2000. ‘Mourning Korean modernity in the memory of the Cheju April Third. Incident.’ Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 1(3): 461-476.

Ko, Sanghyŏn 고상현. 2020. ‘제주신축 공사현장서 타워크레인 전도…800가구 정전. [A Tower Crane Collapses at a construction site in Cheju…800 households Experiences Power Outage].’ 노컷뉴스 [Nocut News], 3 November. https://mjeju.nocutnews.co.kr/news/5440824.

Koh, Sungman. 2015. ‘Transitional Justice, Reconciliation, and Political Archivization: A. comparative study of commemoration in South Korea and Japan of the Jeju April 3 Incident.’ In Routledge Handbook of Memory and Reconciliation in East Asia, edited by Kim Mikyoung, 287-303. New York: Routledge.

Lennon, John and Malcolm Foley. 2020. Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster. London: Continuum.

Mignolo, Walter. 2002. ‘The Geopolitics of Knowledge and the Colonial Difference.’ The South Atlantic Quarterly 101(1): 57-96.

Pyŏn Sangch’ŏl 변상철. 2020a. ‘간첩으로 만들기 딱 좋은 제주사람들 [Jeju People who are Perfect to be “Turned into” Spies].’ OhmyNews, 26 December. Available at: http://omn.kr/1r3hv.

Pyŏn Sangch’ŏl 변상철. 2020b. ‘아버지의 무서운 과거…편지 한 통 남기고 떠난 아들 [Dreadful Past of the Father… A Son Who Left with a Letter Behind].’ OhmyNews, 7 November. http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/View/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0002684637.

Roberts, Brian Russell and Michelle Ann Stephens eds. Archipelagic American Studies. Durham: Duke University Press. 2017:30.

Ryang, Sonia. 2013. ‘Reading Volcano Island: In The Sixty-Fifth Year of the Jeju 4.3 Uprising.’ The Asia-Pacific Journal 11(36): 1-18. Available at: https://apjjf.org/-Sonia-Ryang/3995/article.pdf.

Stratford, Elaine. ‘Imagining the Archipelago.’ In Archipelagic American Studies, edited by Brian Roberts and Michelle Stephens, 74-94. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

The National Committee for Investigation of the Truth about the Jeju April 3 Incident. 2014. The Jeju 4.3 Incident Investigation Report. Jeju: Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation.

Thompson, Lanny. 2017. ‘Heuristic Geographies.’ In Archipelagic American Studies, edited by Brian Roberts and Michelle Stephens, 57-73. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Tong-a Ilbo. 1932. ‘500명 해녀단 주재소를 대거습격 [About 500 Sea Women Attack the Police Substation].’ 동아일보 [Tong-a ilbo], 26 January.

Notes

For a more detailed discussion on woodblock art as resistance in Korea’s democratization movement, see Hoffmann, Frank. 1997. ‘Images of Dissent: Transformations in Korean Minjung Art.’ Harvard Asia Pacific Review 1(2): 44-49.

For the Japanese version of the book, see Kim, Bong Hyun and Kim, Minju. 1963. Chejutō jinmintachi no 4.3 busōtōsōshi [Cheju Islanders’ History of the 4.3 Militarized Struggle]. Osaka: Kōyūsha.