Abstract: In this introduction to an excerpt from Durian Sukegawa’s travel memoir A Dosimeter on the Narrow Road to Oku, I give an outline of Sukegawa’s biography, his reasons for undertaking a journey by bicycle in 2012 along Matsuo Basho’s route in The Narrow Road to Oku, and the reasons for my own particular interest in this text. The translation covers the section of his journey from Fukagawa to Nasu. It won the 2021 Kyoko Selden Memorial Translation Prize in Japanese Literature, Thought, and Society.

Keywords: Durian Sukegawa, Matsuo Basho, Fukushima Daiichi, radiation, contamination, Tokai Daini

Cover of the Genki Shobo edition of A Dosimeter on the Narrow Road to Oku

A Dosimeter on the Narrow Road to Oku (Senryokei to oku no hosomichi) by Durian Sukegawa was published in 2018 by Genki Shobo, awarded the Japan Essayist Club Prize in 2019, and released in paperback by Shueisha in 2021. What sets this account of following Basho’s route in The Narrow Road to Oku apart from others is that Sukegawa travelled by bicycle and measured radiation levels at every point where Basho wrote haiku, it being 2012, the year after the Fukushima disaster. Thus, his journey can be also be read as a set of data demonstrating the extent of contamination over an area bounded by the Pacific and Japan Sea Coasts with the mountain country of Tohoku and Hokuriku in between.1

Cover of the Shueisha edition of A Dosimeter on the Narrow Road to Oku

Sukegawa’s original intention had been simply to write a modern study guide to Basho’s classic volume for high school students. However, when he realized that a significant portion of the route overlapped with the disaster-affected areas, he expanded his mission into a personal investigation of the extent of contamination, and a survey of people’s lives in affected areas, especially those in places where the mass media did not go. In addition, since he would also be travelling deep in rural regions and in the vicinity of nuclear power plants on the Japan Sea coast, he anticipated there would be ample opportunity to observe and reflect on pressing issues facing the country at the time, such as energy availability and rural depopulation.

Such a project was characteristic of Sukegawa, as a concern with injustice and listening to people’s voices was a hallmark of his professional activities. He had studied for a degree in Eastern philosophy at Waseda University and hoped to work in publishing or media-related fields, but discovered in his final year during job recruiting season that such companies would not accept anyone who was color blind in their intake of new graduates. Thus he was forced into independently forging out a career and became a magazine and broadcast writer, reporting from places such as Cambodia, and Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall. He sang about social injustices as the lead vocalist in the popular spoken-word rock band The Screaming Poets from 1990 to 1999, and as a late-night radio personality he attracted a huge following amongst high school students from 1995 to 2000 on the award-winning Nippon Radio program, Durian Sukegawa’s Radio Justice. He presently teaches literature at Meiji Gakuin University, focusing on the literature of Hansen’s disease and Okinawan writers. In his own novels, he explores the philosophical dimensions of ‘listening’ and highlights the situations of victims of discrimination and those living at the margins of society. These have included former Hansen’s Disease patients in Sweet Bean Paste, for example, homeless people and sex-workers in Mizube no Buddha (Buddha on the Waterside), and various social misfits who gather in Golden Gai in Shinjuku no Neko (Shinjuku Cats), to name a few.

Aware of widespread anxiety about radiation in 2012, Sukegawa devised a ‘peace of mind scale’ for the purpose of his journey, which was based on the government-stipulated acceptable annual radiation dosage. His logic was that it would be reasonable to assume that anywhere with readings higher than this officially-mandated figure would be places where inhabitants had reasonable cause to be anxious about their living environment.

The following translated extract covers the section of his journey from Tokyo up to Nasu in Tochigi prefecture. Along the way he passes through Nikko and discovers unacceptably raised levels in the famed Nikko Toshogu Shrine complex, where tourists thronged, oblivious of the risks. At the Rear View Falls he is shocked by an even higher reading, and wonders about the safety of drinking water and agricultural production in a place where both activities appeared to be continuing as normal.

As his journey progressed and subsequent readings revealed the widespread and erratic scattering of cesium contamination, it began to dawn on Sukegawa that making his findings public could have unintended consequences. If he did publish a book, would he be fanning consumer anxiety anew? Would it cause further suffering for those already hit by the loss of communities and livelihood? Or perhaps he would be bringing new misery upon others who had so far lived without the stigma that contamination brought with it?

Sukegawa struggled with this dilemma for years until he decided to publish in 2018. His reason for doing so then was because of the urgent need he saw to counter the effects of fading public memory, which he feared would play into the hands of powerful interests in the nuclear industry anxious to get back to business as usual. He also thought it wrong that the reactors, which had ceased operating since 2011, were being restarted despite numerous unresolved issues in the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster, while many people who were still suffering as a result of the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown. In the following translation of the foreword that Sukegawa wrote in 2018 as an introduction to his 2012 diary account, he talks about the nature of memory and its role in controlling the narrative.

I first learned of Sukegawa’s journey in 2016 before it was published in book form, at a spoken word performance he gave in Nasu, at a farm he had originally visited in 2012. That day I had gone unannounced to introduce myself after being contracted to translate his novel Sweet Bean Paste. I did not know beforehand what the performance would be, and was both surprised and deeply moved by it. The first reason for this is because I had had personal experience of being affected by fear of radiation, but never had I heard anybody acknowledge its significance, or even try to quantify it. The second is because I saw someone attempting to publicly express resistance to the forces of officialdom and big business that comprise the so-called ‘nuclear village,’ which was in accord with the deep-seated anger that I myself harbored but could not adequately express.

My experience of the nuclear village stems from the fact that I have lived and worked in it for the last 35 years in a very literal sense. Ever since marrying a Japanese nuclear research engineer, my home has been in Tokai-mura, Ibaraki prefecture, 110 kilometers north of Tokyo on the Pacific coast and approximately 80 kilometers south of the Fukushima Daiichi complex. Tokai-mura is where Japan’s first research reactor began operation in 1957, and the first commercial reactor was decommissioned in 1966. A second commercial reactor, the Tokai Daini reactor was in operation from 1978 until March 2011, when it stopped automatically following the earthquake. It remains out of operation, although it has in theory received approval from the Nuclear Regulation Authority to restart. There is also a nuclear fuel reprocessing plant being decommissioned (but still with large volumes of highly radioactive waste spent fuel in situ), and numerous other nuclear related facilities and businesses in the town, all less than five kilometers from my doorstep (Tokyo Shimbun 2022).2

I used to believe that nuclear technology was safe, otherwise why would we be allowed to live in such close proximity to all this?

The Tokai Daini and Daiichi reactors, seen from the public Visitors Center car park. Image provided by Alison Watts.

My faith in the authorities’ competence to safely administer it, however, was first shaken after the criticality incident at the JCO Co. Ltd site on September 30, 1999.3 We were ordered to shelter indoors for 24 hours with no information whatsoever, except that coming from the national cabinet secretary on TV. It was a terrifying experience, that gave me a taste of the fear that a radiation emergency can cause. In the following weeks I also witnessed how lack of information also contributed to acute mental distress and anxiety. Despite the experts’ monitoring of radiation levels (Tanaka 2001), there was no mechanism for conveying this information to the public, and for weeks afterwards, long after the danger of contamination from ambient radiation had passed (Tanaka 2001, S1), residents of Tokai-mura and neighboring cities were being urged to undergo body radiation checks and other health tests. All of this only served to suggest to the public that there was still a present danger. It created entirely unnecessary mental stress, in my opinion.4 Letting the public know that the type of radiation emanated—neutron and gamma in this case—have half-lives of less than an hour, would have been a far more effective way of assuaging public anxiety. When the causes of the accident came out—taking shortcuts and lax oversight by government officials—my trust in the authorities to safely oversee nuclear facilities was further undermined. When the Fukushima disaster occurred, and once again radiation contamination became a real fear in Tokai-mura, it blighted my life and that of residents in the town for a long time afterwards.5 Once again I became painfully aware of the authorities’ lack of understanding about the psychological effects of fear of radiation, and doubts about the verity of official pronouncements.

I came to Japan initially in a pre-internet era with a degree in English literature knowing no Japanese. Because of the language barrier it took me a long time to learn in depth about the town where I ended up living and raising a family. But I studied the language and, after decades of active engagement in the local community, have a broad network of friends and acquaintances connected to many sectors, including journalists, local politicians, bureaucrats, the power company, and research institutes. I have served on local and prefectural level government committees in town-planning, gender equality and sister city relations, participated in study tours, nuclear emergency evacuation drills, and been the translator and English voice for local administrative and emergency announcements, amongst other things. In short, I have seen close-up how the mechanisms of local government work, and as a result I have come to believe that ultimately it functions for the purpose of serving the interests of big business and powerful political parties, not residents or the local community. I also have no faith in the competence of the system to safely administer every aspect of production related to the generation of nuclear energy. It is not surprising that Sukegawa’s book resonated so deeply with me.

I was captivated by it as a work of literature too. The style is simple and direct, with occasional flashes of lyrical description, wry humor and haiku moments. The cumulative effect of Sukegawa’s observations about the landscape, people and places he visits, the things he sees and does, and the unflinching observations about his own state of mind and failings, adds up to a compelling and unvarnished portrait of modern Japan and its people. As a work of creative nonfiction, the book is at once travelogue, literary exposition, reportage, philosophical reflection and quiet protest, resonating across time in its juxtaposition of the author’s contemplation of issues fundamental to modern society—energy supply, depopulation, nuclear contamination and waste disposal—with the landscape of Basho’s journey and haiku.

In 2019 Sukegawa also toured the Fukushima Daiichi plant. He wrote about this in an article that I translated for Asymptote, which has accompanying teaching materials and an interview with me.6

Even now, eleven years after Sukegawa’s original journey in 2012 and five years after publication of his book in 2018, the same problems remain: there is still no permanent storage place or comprehensive plan for disposal of nuclear waste, and there is still no viable nuclear emergency evacuation plan in Tokai-mura, where I live, and in many other towns that host nuclear reactors. Yet the system grinds on inexorably, in the interests of Japan’s nuclear village. The least we can do is to not forget about the human and environmental toll of the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Excerpt from A Dosimeter on the Narrow Road to Oku

By Durian Sukegawa, translated by Alison Watts

Foreword: Things We Forget

Where is the dividing line between memory and oblivion?

“It was so long ago I don’t remember” is a common phrase, as if oblivion grows thicker in proportion to the passage of time. But is this really true? Is time a yardstick by which we can gauge the quality of memory? If so, then our perceptions of life would hinge solely on recent events and memories of childhood count for nothing.

I think I am someone who remembers childhood experiences well. Light gleaming in the forest as I push through it in pursuit of insects, a chorus of birdsong, flickering sunshine filtered through trees, the laughter of friends who walked beside me, and the tartness of stolen persimmons. Each individual memory is trifling in itself, but the vivid fragments of sights, sounds, and smells of that time converge into a shimmering cloud that hovers over the margins of my world. At the same time, however, I forget many things, despite having experienced them more recently. Why I was laughing with someone in a bar late at night, the content of a book I read a month ago, or what I ate for lunch the day before yesterday. These things can vanish completely from my mind.

Memories we retain despite the passage of time are often those of life-shaking moments, that were joyful or sad. Somewhere deep down, a door opens and shuts, sealing in the experience as a memory that defies time. First experiences, for example, are often preserved: the first taste of pizza, the first fish caught, the first sight of strange fruit in a foreign country. And naturally, a first kiss. Other firsts are usually tucked away somewhere in the drawer of memory. A first experience moves the heart, and once moved, the heart remembers. However, there are some instances when it is difficult to dissect memory in this way.

The enormous earthquake and tsunami that occurred in Japan on March 11, 2011 was a lesson in the immense destructive power of nature. The loss of life was appalling. At the time I felt helpless and paralyzed in the face of the dismay and terror I could imagine the victims felt, and the grief of those left behind. Then we began to witness more scenes of loss, when forests and rivers, towns and villages, the sky and sea became blanketed with invisible contamination due to the nuclear accident at Fukushima, and we began to witness more scenes of loss. I felt a powerful sense of malaise then, as if the earth were crumbling beneath my feet, and unable to comprehend, I turned my face to the heavens.

This is how I recall that March: with memories so heart-wrenching I thought that time would never be forgotten, I thought it would remain in my own and everybody’s minds for a long, long time to come. At least that is what I believed.

Since then a giant concrete wall has been constructed all along the coastline of Fukushima and Miyagi prefectures, dominating the horizon and robbing people of their view of the sea. Alleviating terrifying memories of towns being engulfed by tsunamis is given as one justification for continuing this engineering project, despite residents’ protests that not being able to see the sea at all is far more frightening.

Meanwhile, strangely enough, the nuclear power plants are restarting operation. The policy of phasing out the use of nuclear energy that was decided on by the administration in 2011 has been spectacularly smashed and dismantled, and the current administration now appears bent on continuing to pursue the use of nuclear power.7 As if all problems have been solved and Fukushima restored to exactly as it was before the accident.

What are we to make of this? If the memory of the tsunami is an unshakable justification for the construction of a giant seawall, why then is there an attempt to wrap the nuclear disaster in a veil of oblivion? Though we are told that reconstruction progresses, the areas where there was forced evacuation because of radioactive contamination, have not gone away. Many people still live in temporary housing, unable to return home. There is still no final storage site for contaminated soil, nor even any method of processing it. Rather, clusters of black plastic container bags packed with highly toxic soil dominate the coastal regions of the disaster.

If my eyes and my memory are to be believed, the grave aftermath of the nuclear disaster is still a long way from being resolved.

An increasing number of children in Fukushima prefecture are becoming afflicted with thyroid cancer.8 Expert opinion is divided between those who will admit no causal link to the nuclear accident and those who believe one is highly likely, but surely the surveys ought to continue if there is any doubt. One would think that an ongoing investigation into the effects of low-level radiation exposure on the human body over the next few decades would be vital, an issue of national concern even.

For some reason, though, oblivion has descended: parts of Fukushima prefecture have disappeared from public consciousness, fields that are no longer safe for growing crops have been abandoned and left to go wild, and people still living in temporary housing have become invisible, forgotten in the shadow of an economy geared toward the Olympics. The horrifying footage of helicopters dumping seawater over nuclear reactors in meltdown is now nothing more than a curiosity buried online, while one by one the country’s reactors resume operation.

What is happening here? My gut instinct is to dislike the way this is playing out. I do not believe that all necessary debate and verification has been carried out. My sense is that this oblivion is arbitrary; that the things we forget, and the things we are being led to forget, are linked to swelling the coffers of vested interests.

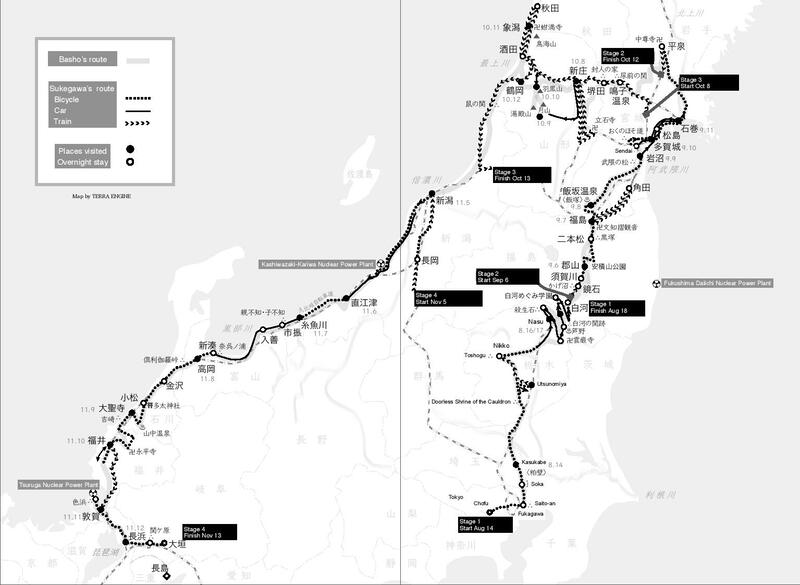

From August to November 2012, the year after the disasters, I traveled approximately 2000 kilometres along the entire course of Matsuo Basho’s route in The Narrow Road to Oku, carrying a dosimeter to measure radiation. I rode a fold-up bicycle as far as it would take me and otherwise traveled by train, or accepted rides in cars and trucks.

The journey came about because I was attempting to write a book. In high school I had struggled with classical Japanese. Not because I was incapable of understanding despite my best efforts, but because I was in the science stream and saw no point in having to memorize a language that was not used anymore. I found classes and exams unbearable. The way we were taught, however, was also a factor, with the teacher constantly thundering “Conjugate!” at us while rapping on the desk with a bamboo pointer. He had a peculiar zeal for expounding on trifling grammatical points rather than what was actually written in the ancient texts. As a result, I became the kind of student who switched off automatically at the mention of classical Japanese.

But of course I could not avoid it forever, not least because I had spent the last twenty-five years or so making a living from the crafting and manipulation of words. It began to occur to me that there had to be hidden treasure in texts that had been read continuously through the ages, and that to go through life without discovering them would be a great pity. So I bought a text book aimed at high school students and, with a classical Japanese dictionary at my side, set about reading ancient diary literature and dramatic recitations. Combing these texts for hours without being harangued to “Conjugate!” was truly pleasurable. I could focus on them as literature, and enjoyed figuring out the content and learning how people in the past had lived.

…

Of course, I understand the importance of knowing the grammar and archaic vocabulary now, and I don’t dispute it. Literature is full of nuance, and it is not acceptable to skate over the finer points. Nevertheless, I believe things could be done differently. Priority could be given to stimulating interest in the classics for children who are about to begin studying them. Bring a story alive by telling students about the joys and woes of people in the past rather than simply trying to trip them up on grammar. Studying the maps in order to climb a mountain may be necessary, but in my opinion it is far more important to look at the mountain first and know its beauty in order to feel positive about it climbing it.

Then I had an idea. Increasingly people were reading The Tale of Genji in modern Japanese translation, so why shouldn’t I translate the classics most likely to be used as high school texts into easy-to-understand Japanese? They would not have to be thick tomes. Students could use them as introductions to classic texts, and I would have work. It would be a win–win situation. I thought of French entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre, who, despite being born into poverty, produced more than fifty reference texts on insects and spiders and supported his family on the royalties. I felt encouraged by his example, as it was a long while since I had made a decent living from performing and writing.

I set about choosing a text for my big debut. Since it was to be used to study for university entrance exams, a book that often came up would be best, something like the twelfth-century historical tale The Great Mirror. But that seemed too difficult. My ideal was an early modern text that was not too long, did not contain too many archaisms, and was on a subject that anybody could enjoy. It didn’t take me long to settle on Basho’s The Narrow Road to Oku. Having read Donald Keene’s translation into English, I could envision exactly the kind of plain, spoken language it could easily be translated into. I got straight to work in my free time and in less than two weeks had completed the first draft. It had taken much less time than I expected, but something did not feel right. In the course of writing, I had begun to imagine I could hear the voice of Basho himself, berating me: this is not you, he would say.

In my previous life as a singer in a punk rock band called The Screaming Poets that I had founded, I used to give spoken-word performances based on my travel experiences and thorny issues they had raised for me. In Eastern Europe I had observed a revolution that shook up the Cold War structure, I had seen the minefields of Cambodia, and I had been to places like India and the Galapagos Islands that inspired me to think about life in a biological and philosophical sense. Encounters with people, their words and lives, had led me to think deeply about the human condition and to attempt to sing about it. But it was my travels that enabled me to write in the first place. Above all, I was a traveler.

Yet here I was, a middle-aged man attempting a modern translation of The Narrow Road to Oku without even leaving my study. By my own standards I had sunk low. How could I even think of attempting to write a substitute for one of Japan’s greatest works of travel literature without making the journey myself? Could anything be more inauthentic? How could such laziness be excused? What did I think I was doing? The accusations echoed constantly in my head.

Something else occurred to me: the journey Basho and his traveling companion Sora had made in 1689 had taken them through Tokyo and the modern-day prefectures of Saitama, Ibaraki, Tochigi, Fukushima, Miyagi, Iwate, Yamagata, Akita, Niigata, Toyama, Ishikawa, Fukui, Shiga, and Gifu. In 2012 this route included areas affected not only by the tsunami but also wide stretches of the Pacific Ocean coastal area contaminated by radioactive fallout. Additionally, the segment along the Japan Sea coastline included two prefectures that cannot be spoken of without mentioning their nuclear power stations.

In short, to retrace Basho’s route in this day and age would not only be a reenactment of an Edo-era haiku travelogue, it would also force me to squarely confront the issues of the day in both a physical and intellectual sense. Once I realized this, I had no choice but to go.

My plan was to spend one week a month on the road, then return to Tokyo for work. I would travel by folding bike, which I could pack up and carry back on the train. Then the next month I would return to where I had left off and begin pedaling again. This was to be a relay-style journey along the narrow road.

When I set out in August 2012, the heat was so intense I feared I might collapse from heatstroke. Any water I drank soon dissipated as sweat. At the other extreme, when I reached the peak of Mount Gassan in October it was already iced over, and when my travels drew to a close in November the mountains of Hokuriku were powdered with snow. At fifty years of age it was a tough journey, both mentally and physically. But in truth, the internal conflict and indecision I was left with at my journey’s end became the greatest ordeal.

…

In places affected by contamination, people were trying to rebuild their lives. For anybody with a business or simply trying to get on with life, I would not be doing them a favor by publicly announcing radiation levels in their neighborhood. There was, however, another argument: many people were suffering in silence, unable to protest against the damage that had been inflicted on them. With the country now on the way to becoming a nation of nuclear power once again, it could be a meaningful act for me to give such people a voice by writing about them.

During my journey I anguished over which course to take. My journal is a reflection of this dilemma and as such simply a faithful record of my feelings at the time. Please take it for what it is.

In the end I decided to go public, because oblivion should not prevail. We should not allow ourselves to be unthinkingly swept along by a forgetfulness that is convenient to the authorities.

The first half of my travels was dominated by encounters with people and by various eye-opening experiences. In the second half I encountered far fewer people and I spent a great deal of time talking to myself, ruminating over the things that were weighing on my mind. I have given the real names of some people but use pseudonyms for those who do not wish to be named.

And now, I ask you to join me on my journey by bicycle, pedaling along Basho’s route on the narrow road to the deep north, a year and a half after the triple earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disasters of 2011.

Fukagawa to Shirakawa

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

It was time to hit the road. Time to turn and face the rising sun with a youthful glint in my eye. Slice the early morning breeze as I pedaled for all I was worth to Michinoku… Or so I had imagined, that is, until last night. But it was past nine in the morning, and I was still holed up in my office, lounging around while rain beat down on the thick growth of flowers outside the window.

What a downpour. It had begun the previous evening while I was out for a drink after completing preparations for departure. Weather reports on the internet forecast rain until close to midday. I didn’t much care for getting soaked through at the start of my journey, and so one glass became two, then three, then before I knew it I’d had too much.

Now, my head felt heavy. Far too heavy. But I was determined to leave today.

I was about to embark on a 2000 or so kilometer journey by bicycle. It would be my first experience of long-distance cycling, and having recently turned fifty, I was painfully conscious of how physically demanding a task I had set myself. But despite the white strands starting to sprout on my head, the days and road ahead of me would always unfold anew: I was optimistic about making it.

Map of journey. Courtesy of Shueisha.

My plan was to meet with people along the way who had been affected by the Fukushima nuclear accident. A year and a half since the tsunami, earthquake, and nuclear disasters of 2011, what state was Japan in now? That was the question I was setting out to find answers for, with my own ears and eyes. At the same time, I wanted it to be an opportunity to think about life.

I had purchased a bicycle for the journey, an American-made Dahon fold-up cycle, as most Japanese brands could not support my large frame. The young guy in the bike shop had explained that such a bicycle was not designed for long-distance travel. At roughly twenty-five pounds it was more compact than a touring cycle, in fact it was more like a bike you might ride to the shops than anything else. He must have sensed something. “Where do you plan on going?” he asked, looking concerned. “Saitama, or maybe further,” I hedged, not wanting to complicate the conversation. “Oh,” he mumbled, and we completed our transaction without further comment.

Very soon this bike was to carry me along the route walked by Matsuo Basho and Kawai Sora as described in Basho’s travel classic The Narrow Road to Oku. It would take me to the places they made pilgrimages to, the landscapes of Japan’s past, with the future a steep slope stretching ahead. In the bag attached to the center of the handlebars, I put a camera and dosimeter to measure the level of radiation in the air. I intended to stop in each place where Basho had composed his haiku and take measurements of the radiation there.

Dosimeter attached to the bicycle. Image provided by Durian Sukegawa.

Sometime after noon the rain stopped and at last I heaved the rucksack onto my back. Before leaving, I took a test measurement of radiation in the flowerbed outside my office door. Holding it at a height of three feet, I waited thirty seconds for the average readout to appear. The display showed 0.07, 0.14, and then 0.10. Because radioactive substances emit gamma rays randomly, the readouts are irregular and varied. The final reading is the average, which in this case was 0.10 microsieverts per hour.

Even without nuclear accidents, we are constantly exposed to radiation from natural sources, like the cosmic rays that bombard us from the atmosphere, or radiation emitted from the earth’s crust. We are also subject to internal exposure from the minute amounts of radiation found in food. The global average exposure to naturally occurring radiation is apparently 2.4 millisieverts (mSv) per year. In Japan the average is a little lower, at 0.7 mSv for external exposure and 0.8 mSv for internal exposure, which combined, amounts to a level of 1.5 mSv per year. The burning question post-Fukushima then, is how much has exposure to radiation increased as a result of the nuclear disaster.

The Japanese government’s designated acceptable dosage limit for the general public was one millisievert per year. That was the maximum permissible dose for artificially produced radiation over and above the level of natural radiation. Apparently it does not mean, however, that exposure to a dose in excess of one millisievert is harmful, or that it could adversely affect the human body. The figure of one millisievert was set as a standard in order to regulate exposure to radiation from x-rays and CT scans, and as such is not an indication of danger, according to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

So the question is, how much artificial radiation can we safely be exposed to before the body is damaged? I don’t know. In my reading on the subject I found nothing definitive on exposure to low-level radiation. A basic starting point might be to ask, “can artificial radiation from cesium and iodine scattered as a result of the nuclear accident, be regarded in the same way as naturally occurring radiation?” Or, as scholars who sound the alarm claim, should it be considered a completely different substance? For non-specialists such as myself, it is all very obscure and difficult to get a clear grip on.

Given that accurate data is the foundation of science, it seems to me that we don’t even have enough of a common shared knowledge to understand the effects of radiation on the human body. After the bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the opportunity to establish a cornerstone of ongoing research was lost due to the chaos of wartime.

…

The most destructive nuclear incident since then was, of course, the reactor explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in 1986. This affected not only the Eurasian continent but the whole Northern hemisphere. Plant staff and workers were among the many fatalities, and the incidence of pediatric cancer and children born with congenital abnormalities continues to be high in areas where large amounts of radiation fell.

However, the accident occurred in the former Soviet Union, a country where I think it can safely be said the state is not known for its tolerance of dissenting or inconvenient opinions, and the data from Chernobyl is no exception.

…

Can we take figures published by governments and public officials at face value? The question is vital, not only in the case of Chernobyl, but also for Japan. People everywhere engage in fudging the truth for one reason or another, and the Japanese are no exception. It is not possible for the people of Japan to believe that every senior government official has been totally honest and open with them about the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, or that the government, Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), and scholars have revealed everything about the disaster to the public, that there has been no cover-up of any kind.

The meltdowns that occurred at the Chernobyl and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plants were both recorded as level seven, the worst international rating for nuclear incidents. Yet in the days and weeks after the explosion at Fukushima, the Japanese public was fed a charade of government reports based on comments from Tokyo University academics, which attempted to persuade them that nothing of major consequence had occurred. This is a fact that I am unable to forget.

Everybody knows that exposure to extremely high levels of radiation causes immediate death. What people in Japan live in fear of now, however, are the genetic effects and cancers that develop after continued exposure to low-dose radiation. But because the data from Chernobyl is diverse and varies according to individual or organization, there is no objective data yardstick that could be used to establish guidelines, so that people could know what their chances were of sustaining genetic damage after living for a particular length of time in an environment with a specific level of radiation.

In any case, it is a fact that the Fukushima accident caused cesium with a half-life of thirty years to scatter on a large scale, from the Tohoku region in the north to the central Kanto region, which includes Tokyo and the seven surrounding prefectures. Land on which it should have been possible to live safely, with peace of mind, was transformed into an environment that is a source of psychological and physical harm. Gamma rays emitted from cesium 137 will affect reproductive cells and genes for a very long time to come. When a young girl innocently playing outside today eventually becomes a mother, it cannot be said with any certainty that she will not give birth to a child with congenital abnormalities as a result. This alarming situation will continue for decades to come, hundreds of years even, while the half-life of the radioactive substances decreases.

Anxiety about the potential effects of radiation on health is a cause of great mental stress for many people living in contaminated areas. With this in mind, I decided to take the Japanese government-designated acceptable dose of one millisievert per year for the general public, and use it to devise a standard for mental health, which I call the “peace of mind scale.” It may not be a standard of physical safety per se, but since one millisievert is a figure used for reference, and one which people worry about, I believed it was relevant and meaningful.

To calculate my peace of mind scale I divided one millisievert by 365 days, and then by 24 to obtain the maximum hourly dosage rate that would enable a person to stay under then recommended annual dosage. This result of this calculation was approximately 0.11 microsieverts per hour. However, as the risk of radiation exposure is reduced by staying indoors, and based on the assumption that a person would spend half the day outdoors, I doubled this to reach a figure of 0.22 microsieverts per hour. Any reading over this amount in a particular location would represent a potential annual radiation dosage above the recommended one millisievert, and would as such have a negative psychological impact affecting peace of mind.9

Monitoring posts and dosimeters are designed to deduct natural radiation from their readings, producing figures that can be understood as the actual level of man-made radiation. If a reading is attributed to the nuclear disaster, the cause cannot be iodine—since iodine has a half-life of only eight days and would already have disappeared from the environment—therefore it must be from cesium 137.

The flowerbed outside my door measured 0.10 microsieverts. This could be dismissed as being so small as to be of no consequence, but it is not zero. Radiation from the Fukushima nuclear disaster, albeit a minute quantity, had reached the Tamagawa river region in Western Tokyo. And almost nobody had noticed.

Chofu Office: 0.10 microsieverts

Finally I set out along the Koshu-kaido highway in the direction of Shinjuku, riding a very small bicycle with a large hefty rucksack on my back. The sky rapidly cleared and the sun shone fiercely, as if to make up for lost time that day. Strong sunshine beat down on the still wet road surface and the concrete cityscape unfolded ahead of me through a haze of steam that rose like clouds of breath from the ground.

I was soon dripping with sweat. The humidity was so dense it felt solid enough to grasp. By the time I reached Shinjuku my bottle of water was half empty. I went from Yotsuya to Kojimachi, pedaled down the Miyakezaka slope, did a half circuit around the Imperial Palace, and rode from Babasakimon in the direction of the Kayabacho area. It was hot. So damn hot. The sweat poured out and I was constantly sipping water. There was no question of stopping to rest, however. Already on the first day of my journey I was way behind schedule. How far could I go before dark? Would I be able to find somewhere to stay? Whenever such thoughts crossed my mind the sweat seemed to flow even more profusely.

I crossed Eitaibashi bridge over the Sumidagawa river, turned left and headed for Fukagawa. Then, after crossing several more bridges over a canal, I came to Saito-an, where Basho is said to have begun his journey. By then it was after two. Finally, I had arrived at the start of the narrow road to Oku.

Saito-an is a reconstructed canal-side villa that had once belonged to a follower of Basho’s called Sanpuu. Basho sold his own hut to move here after deciding to journey north to Michinoku, nowadays known as Tohoku. He passed his nights here before the long journey, no doubt thinking of the days to come, not knowing if he would return alive. A statue of Basho was seated on a bench alongside the villa porch. I thought it was rather tasteful. Basho looked wise and thoughtful, a likeable sort of fellow.

Like Basho, I too was about to set out for Michinoku, traveling under the steam of my own legs.

A school of baby flathead mullet swam across the surface of the canal. They too would eventually make a journey, out to sea. This was truly a departure point for travelers.

As I was standing there lost in thought, something about the spirit and quality of the recreated villa began to irk me. I couldn’t but help take issue with its appearance. For somewhere that marks the starting point of a journey in a national classic, it was somewhat … half-baked—to put it bluntly. The area around where Basho was seated was fine—presented in such a way as to suggest the Edo era—but there was an overall sense of incompleteness. It had all the atmosphere of a construction site. I couldn’t understand it. This was an official designated historical site in Koto Ward; why had the ward government not put more resources into it? Or had it simply been flung together semi-complete because that was their idea of what houses of the period looked like?

Statute of a seated Basho at Saito-an. Image provided by Durian Sukegawa.

In any case, it was a photo opportunity. Placing the dosimeter in Basho’s hand, I promptly took a picture.

“Whaddaya doing?” A ramshackle looking man in his late sixties abruptly demanded. His face looked as if it had been frozen, then unfrozen, then refrozen and once more unfrozen.

I told him I was about to set off on a journey on the narrow road to the deep north.

“This place is fake,” he replied. “I know where the real thing is.”

He might well say that, but I was looking at a monument built by the Koto ward authorities, which had inscribed on it in stone that Basho had started his journey from this very spot.

Nevertheless, the man persisted: “The city decided a place like this’d be an attraction, so they just built it.”

Surely not. I suspected him of not knowing the difference between Saito-an and Basho-an, the hut in Fukagawa where Basho had originally lived before moving here. In other words, he believed Basho-an to be a real place but not Saito-an. But no, I misunderstood him, and because I could see the old man had every confidence in himself I asked him to tell me where he thought Basho-an was.

Incidentally, when I checked the dosimeter at Saito-an, the reading was 0.05. This represents an average of less than 0.05 microsieverts per hour, which is tantamount to no detectable radiation. So, from this point on, I counted 0.05 and below as no radiation detected.

Saito-an: No radiation detected

I decided to go to the place the old man had told me about. Mounted on my bicycle I crossed a bridge and rode along the canal, heading for the Sumidagawa river, when suddenly there it was—the site of Basho-an—in the gap between a factory and a line of houses. It was so tiny, had I not been looking for it I never would have noticed. The sign said Basho Inari Shrine.

Apparently, a stone frog believed to have belonged to Basho had been unearthed in this spot after a tsunami swept through in 1917. And, based on this, historians declared it to be the location of Basho’s hut, according to the inscription on the stone monument. That frog is now preserved in the Basho Memorial Museum, in Koto Ward.

I wondered about that. Can they really determine that this was where Basho once lived on the basis of a stone frog? Surely the samurai and townspeople could have had stone frogs in their houses too?

A variety of ornamental frogs were displayed in the shrine grounds, and there was even a retro Showa-era Kero-yon frog doll. This would be the kind of place, I supposed, that frog- collecting aficionados know about. I was reminded of a guitarist I know, who has over five hundred ornamental frogs in his house, and calls his guitar classroom “Frog Cottage.” Green frogs in a red shrine. The contrast in colors was really quite striking.

Even a thatched hut

May change with a new owner

Into a doll’s house.

This is the first haiku to appear in The Narrow Road to Oku. It reveals Basho’s state of mind as he prepared for his journey, and I wanted to believe that the thatched hut referred to had once been on this spot. Basho had sold his own hut to a stranger and rented out Saito-an. Though his mind was occupied with the journey to come, his thoughts still turned to his old home with a touch of sadness. These emotions drive the poem, giving us a sense of Basho the poet.

A short distance from the shrine I climbed the embankment along the Sumidagawa and found another statue of Basho. This Basho was seated formally—kneeling with his feet tucked beneath him—on a large cushion. Unlike the sitting Basho at Saito-an, his face was thin, and he gazed over the river with a gentle look in his eye.

Basho and Sora had boarded a boat here to take them upstream to Senju, where they disembarked and began their walk to Michinoku. And now, the time had come for me too to be on my way. As I set off in the direction of Asakusa, I imagined the lean Basho and Kero-yon the frog giving me a send-off.

Site of Basho’s hut: 0.09 microsieverts

In Asakusa I stopped for a break at a restaurant specializing in beef rice bowls, and ordered an extra-large meal accompanied by an egg and salad for lunch. But it was not pleasant sitting in an air-conditioned interior wearing a T-shirt wet through with sweat. I bolted down my food and returned to the heat of the road.

Continuing on past the Kaminarimon temple gates I headed north along the Sumidagawa, with the Tokyo Sky Tree in view to my right. By the time I left Arakawa Ward and crossed the Senju Ohashi bridge into Adachi Ward, it was past four.

The Senju Ohashi bridge. Image provided by Durian Sukegawa.

Adachi Market was on the other side of the bridge, on the site of the first station on the old Nikko Kaido highway. It was here on March 27, 1689—May 16 in the modern calendar—that Basho and Sora disembarked from the boat and started walking.

Here, too, I found a statue of Basho, one slightly more mangaesque than the previous two, not to mention somewhat rotund. Perhaps he had indulged in too many bananas from the market, in honor of his namesake basho, as the native Japanese banana is called.

I took a photo of the plump Basho then got out the dosimeter. Though I was technically still in Tokyo, on this side of the Sumidagawa river it felt as if I’d left the city behind. Looking back, I could see the skyline of the Arakawa and Taito wards on the opposite bank, partitioned in straight lines by rows of high-rise buildings. In contrast, the rows of old-fashioned shops and houses in Adachi gave me a sense of having traveled back in time while moving forward on my journey.

Numerous friends and followers had come here to bid farewell Basho and Sora when they departed. These friends had lingered, reluctant to leave. Basho, aware of them standing there watching his and Sora’s backs until they were out of sight, wrote almost self-consciously:

Spring is passing by!

Birds are weeping and the eyes

Of fish fill with tears.

This was the first shot fired from his pen; in other words, the first haiku written on the journey. While lamenting the parting from his friends and followers, Basho found their lingering presence slightly embarrassing and was anxious to be away from there.

Senju: 0.09 microsieverts

I turned off the old Nikko Kaido onto Route 4, the modern road to Nikko, and passed through the Takenotsuka district at five. The sun was getting low by then but there was no hint of an evening breeze. Traffic was heavy, and an intense glare reflected off the road. Still sweating profusely, I felt like stopping every time I saw a soft-drink vending machine. I was beginning to have regrets about the journey, thinking that it would have been better to go later in the year if I was going to travel by bicycle, when all of a sudden I saw an elephant that appeared to be leaping onto the footpath. Not a live elephant mind you, simply a sculpture of an elephant outside a stonemason’s shop. Yet I felt that it was watching me. Did Basho know about elephants? There are records of live elephants being sent to Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, but was learning the shape and size of an elephant part of general education for ordinary people in the Edo period, I wondered.

It was after six when I reached the city of Soka. From here on was Saitama Prefecture, and I had well and truly said goodbye to Tokyo. Basho had written that they stayed in Soka the first night. Sora’s diary, however, makes it clear this was not the case. Basho’s journal was not travel writing in the sense of being a documentation of his travels; he would have been writing it as a book of poetry, the fruit of a long journey that encompassed a picture of his inner life. You could argue that it is a fantasy, a journey of the imagination superimposed over a base of real memories. This makes the diary of Kawai Sora, Basho’s follower who walked with him, an invaluable record of the facts. According to Sora’s diary, they lodged the first night in Kasukabe. Soka was merely somewhere they passed through.

Nevertheless, there seemed to be a surprisingly determined effort to capitalize on Basho in Soka. As was evidenced by the fluttering banners along the main street depicting Basho on his travels, and the line of Basho murals along the Ayasegawa river weir. There was even an arched bridge called Hyakutaibashi (Eternal Bridge) in the park by the river. Taken obviously from the opening line of The Narrow Road to Oku: “The months and days are the travelers of eternity.” Apparently it was irrelevant whether Basho had really stayed there or not. Still, children ran happily back and forth across this bridge in the park at dusk.

I came across another statue of Basho here, in the park. This one was in an elegant setting, surrounded by crepe myrtle flowers in full bloom, but was covered with bird droppings and somehow looked tired. That’s as it should be, however; in the original text, only five miles into their travels on the first leg from Senju to Soka, Basho wrote: “The first pain I suffered on the journey came from the weight of the pack on my scrawny shoulders.”

Despite having just begun, Basho was weighed down with parting gifts that he had been unable to refuse in spite of the burden, so his shoulders hurt. I understood Basho’s pain; by then, my behind was also hurting. I pulled out my smartphone to search for accommodation in Kasukabe, and phoned the cheapest business hotel I could find.

“We have a vacancy. What time will you arrive?” said the young woman who answered.

“I’m in Soka now,” I told her, and explained my situation.

“Oh, you’re on a bike? In that case it’ll be another two hours or so,” she informed me.

Another two hours? I groaned, kneading my back as I stared at the cars zooming by.

At sunset I was still riding along the Ayasegawa. This river had once been your typical chemical sludge, always ranking last in national water quality ratings. But the water quality had gradually been improved over the years, though it was still a long way from being an environment in which children could safely play. Still, it was beautiful at evening with the river surface a mirror that reflected all the light cleaving the sky. Some pollution is visible to the eye, and some is not.

Soka, Ayasegawa riverbank: No radiation detected

Ayasegawa river at sunset. Image provided by Durian Sukegawa.

I pedaled hard, bent on getting to Kasukabe, and reached Nishigaya. At some point along the way night had fallen. I was riding along the National Route 4 Highway, with cars whizzing by at high speed, and forced in places to detour around roadworks and ride on the crumbling edges of the road shoulder. Sweat began dropping on the lenses of my glasses. It was already difficult enough to see in the pitch dark with my aging eyes, but on top of that I was periodically blinded by the glare of headlights. It occurred to me that traveling by night might be too dangerous, when I spotted a bar with the name Ca va? “Oh, I’m fine. My butt hurts, that’s all,” I muttered in reply. It has to be said that one of the attractions of a journey by bicycle is the opportunity to observe shop signboards and other curiosities en route, which ordinarily you might fail to notice.

Nishigaya: 0.09 microsieverts

Finally, I arrived at the hotel in Kasukabe. In person the young woman in reception I had spoken to on the phone earlier, reminded me slightly of enka singer Aki Yashiro. “Park your bike outside the front entrance so it won’t get stolen,” she instructed me.

After showering, I washed my underwear and T-shirt by hand and hung them to dry from the air-conditioner vent, where they proceeded to drip onto the bed. Damn. But there was nowhere else to hang anything in the cramped room. What did Basho do about laundry on his journey?

In Basho’s day the town name of Kasukabe had been written with different characters, which were still in use evidently, I discovered, as I wandered around the Kasukabe Station area. Coming across a modest-looking Chinese restaurant, I went in and ordered a double serving of gyoza with a large mug of beer. A young couple and a little girl who must have been about five were seated next to me, eating a proper meal. The little girl was in good humor, for she giggled in answer every time her mother or father spoke. Her voice was so sweet and natural it made me feel good just hearing her. Next to this family, wrapped in their cocoon of happiness, the effects of beer mingled with exhaustion until I became almost unable to move.

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

At the start of my second day once again I’d drunk too much the night before. Once again, my head felt heavy. I sat on a park bench at seven-thirty in the morning and did some soul searching over a ham sandwich.

When I measured the radiation in Kasukabe, I got an average reading of 0.14 microsieverts per hour. Since this was the level on an asphalt road surface, it would probably be slightly higher in gardens and grassy areas. Zero point one four microsieverts, twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year, amounts to an annual dosage of 1.23 millisieverts. This figure might not seem significantly high, but for people working outside the whole day, it would bring them over the Japanese government’s designated maximum dosage of one millisievert per year, and it certainly ranked negatively on my peace of mind scale.

Was this to be the start of discovering more hotspots, I thought, as I headed north along Route 4, in the same blistering heat and humidity as the previous day?

The scenery became more varied when the highway traversed the city of Kuki, as irrigation canals, rice and vegetable fields became a constant in the landscape. About half of all vehicles in second-hand car yards I saw were rotary cultivators and tractors. Damn, it was hot. On impulse I stopped to stare at an irrigation canal, seriously contemplating diving in for a swim.

Kasukabe: 0.14 microsieverts

I reached Satte city. Route 4 continued, straight ahead. Strictly speaking, I should be riding on the road, but since I was carrying a large rucksack and was not on a touring cycle, I rode on the footpath wherever it looked like that might be permitted. This, however, was becoming more and more difficult. Along with the proliferation of fields, was an increase in weeds growing on the sidewalk. In places waist-high vegetation even completely blocked all passage. Maybe pedestrians didn’t come along here because the wild growth of summer weeds was too much for them. In any case, it was challenging to ride a bike on the sidewalk. But riding on the road was a frightening alternative, as heavy trucks sped past at high-speed, right up close. There was nothing for it but to forge on through the dense forest of weeds.

Satte: No radiation detected

At ten thirty I crossed the Tonegawa river into the city of Koga, Ibaraki Prefecture. Here, the expanse of green riverbed flats was such a refreshing sight that I stopped to rest for a while. The occasional breaths of cool air blowing off the river through the hot air made me feel better.

If all the landscape was like this, a cycling tour would be a treat for the eyes, but what I mostly saw along Route 4 was abandoned shops and drive-in businesses that had folded. Businesses established by people with dreams and families to support. You don’t have to go far from Tokyo before the reality of Japan becomes glaringly apparent.

A large brown cicada lying on its back was also not a pretty sight. But when I picked it up, it did a circle in the air before landing on my waist bag. Now I too had a buddy to accompany me under the blazing sun. It felt good to have a living creature as a traveling companion for a brief time.

Koga: No radiation detected

I passed a sign announcing the border with Tochigi Prefecture. My mood swung between elation at having made it this far by bicycle, and torment at the now persistent pain in my derriere. How could it hurt so much on only the second day? Would I get used to this?

Rice paddies stretched endlessly through the districts of Nogi and Mamada, until I came to the city of Oyama. It was so hot that I stopped there to enter an enormous shopping center sprouting from the middle of fields alongside the highway. Inside I ordered an iced latte at Starbucks and basked for a while in the breeze from an air-conditioner. Inexplicably, there was a merry-go-round, where parents stood waving to their children as they sat astride the horses. What was this place? I went out to look and found a sign that said ‘Site of the Oyama Amusement Park’. The name was familiar, though I had never been here before. Staring at this sole remaining ride going round and round, stirred up memories. I recalled the now defunct Hanshin Park from my childhood, which used to have an animal called a leopon, the crossbreed offspring of a lion and a leopard. I doubt if operators going to such lengths to draw customers would be tolerated today. The concept of amusement parks is a long way from what it used to be when I was a kid. Times had changed, and I hadn’t noticed until now.

Site of the Oyama Amusement Park: No radiation detected

I had lunch at a beef bowl restaurant again, and then turned off Route 4 to continue north along Route 18, a smaller prefectural road. It followed the Sugatagawa river, going up and down and up and down, and past the Tochigi Prefecture Prison. Then, after two, I came to an imposing avenue of sturdy tall cedars, pointing straight up at the heavens. This was Omiwa Shrine, site of the Doorless Shrine of the Cauldron, also known as the Eight Island Kilns, the first of places made famous in classical Japanese poetry to be mentioned in The Narrow Road to Oku.

Basho’s journey had been born of a desire to see this and many other such sites extolled in poetry since ancient times. He seems to have been inspired in particular by the favorite spots of Saigyo and Noin, the top billing stars in the world of waka poetry. Sora had the task of researching how to get to each place, so having made a careful study of the Doorless Shrine of the Cauldron, he was able to provide Basho with the background story, recorded in The Narrow Road to Oku, which goes roughly like this: The shrine is dedicated to the goddess Princess Flowering Blossoms, who managed to get pregnant even though she only did it once with her husband. He became angry, suspicious that it might not be his child, so the princess fled into the doorless shrine where she set herself on fire. As flames rose up she gave birth to a child called Prince Fire Bright.

What a singular image … I gulped at the thought of that happening in reality. According to Sora’s research, Princess Flowering Blossom came from the same ancestral line as the goddess worshipped at the Mount Fuji Sengen Shrine, making her a goddess of volcanoes as well as safe births. Which is why smoke—i.e. water vapor—was said to rise off the eight islands in the small lake, and it became de rigueur for poets to make reference to it in their poems. For a time I stood staring at the water, but failed to spy any smoke. However, I can say that the area is paradise for frogs. When I picked up a ladle to pour water over my hands for purification—as is customary before entering shrines and temples—four tree frogs suddenly leapt out. To see not one but four frogs jumping with such vigor, here at the first of famous places on a journey following in the footsteps of Basho, felt truly auspicious.

I also saw three deliverymen napping in the shade of the trees. I’m not sure that was legit during working hours, but who could blame them in this heat. They made quite a picture. And such blatant slacking off was sort of refreshing.

Leaving the Doorless Shrine of the Cauldron behind me I got pedaling again. The countryside around here was devoid of people going out and about. A lone vending machine beside the rice fields beckoned me to stop for a drink. I discovered it had Nectar, a drink I’d often had as a child, so I bought it without hesitation and got a boost of energy from the canned artificial sweet peach aroma that assailed me for the first time in decades. Maybe I should write a history of life in the Showa era, tracing this aroma in my memory.

Tochigi City, Doorless Shrine of the Cauldron: No radiation detected

It was after three when I entered Mibu, a town with unique charm. In Saitama Prefecture you have the old highway city of Kawagoe, known as Little Edo for its lingering ambience of old Tokyo. Mibu was similar in having a quality that evoked times past but what made it different from the bustling tourist destination of Kawagoe was the silence. Apart from birds chirping and the cry of cicadas, I heard nothing. I was tempted to stop and look around some of the old buildings there, but a detour was out of the question now. I made a mental note of Mibu though, as somewhere I’d like to return to.

From Mibu the old highway to Nikko threaded through a rice belt with fields extending in all directions, and cedars lining the road. Once again I oscillated between exhilaration at being part of this wide landscape, and the nagging pain in my behind. ‘Be in good health!’ a row of tiny ancient Jizo statues seemed to whisper at me as I rode by.

I came to the Niregi district in Kanuma city and kept on pedaling. The heat was unrelenting. Deserted sidewalks, however, offered hints of an approaching change in season in the form of fallen chestnut burrs, albeit green, sprinkling the sidewalks.

Nikko Kaido, Mibu, Niregi: No radiation detected

My final destination for the day was Kanuma. Arriving in the city just before six, I was dripping with sweat, and desperate for a shower and beer as quickly as possible. Having done my homework and researched in advance the only business hotel in town, I pulled out my smartphone to make the call, only to hear a recorded voice announce: “this number is no longer in use.” How could that be, when this was the only hotel in Kanuma?

Anxiously I checked the internet again and discovered that the hotel had shut its doors the previous month. All day I had been pedaling toward a place with no accommodation.

What was I to do? It was already getting dark. And I was too old to sleep in the open anymore. A further search for cheap accommodation in the vicinity only turned up places in the city of Utsunomiya, which was a long way from Kanuma. I couldn’t keep standing around though, and called to make a reservation at a business hotel in Utsunomiya.

Then I rode nearly another twenty kilometers to the hotel near the Tochigi Prefectural Office. Not only was I riding at night again, I was also going further and further in the opposite direction from my next day’s destination of Nikko. Worse still, my bottom was now seriously aching. Ah, such was the reality of my casual approach to travel planning.

And so, it was past ten at night by the time I dragged myself out on stiff, weary legs in search of beer and a plate of Utsunomiya gyoza dumplings.

Kanuma: No radiation detected

Thursday, August 16, 2012

Morning of the third day. Between the pain in my butt and stiff leg muscles, I walked like a robot. It had begun to dawn on me that perhaps a long journey by bicycle required some refined planning, like a softer saddle, and padded cycling pants. I hadn’t yet decided on how far I would go for this leg of the journey, but these were things I needed to think about immediately once I got back to Tokyo.

I couldn’t face riding back over the extra twenty kilometers I had covered last night, so I decided to backtrack by train. Before leaving, I put the dosimeter in a plant bed outside Utsunomiya Station, just to see. The reading was 0.14 microsieverts per hour, the same as at Kasukabe. Not enough to raise eyebrows perhaps, but cesium had definitely fallen here.

JR Utsunomiya Station: 0.14 microsieverts

I folded up my bike and stored it in its case, then boarded a train on the Nikko Line. What a breeze it was to travel by train. After having relied on my legs to get me this far, to simply sit and be propelled forward felt truly modern. Ah, the bliss of train travel … it was all too easy.

Gazing out at the scenery through the windows, I tried to imagine what Edo-era style travel would be like. In The Narrow Road to Oku there is no mention of the journey from the Doorless Shrine of the Cauldron to the station town of Hatsuishi at the base of the Nikko mountains. Sora merely noted the course they took. Since nothing of consequence was recorded, I had no choice but to picture it for myself; Basho talking in what I guess would be a Kansai accent, since he was born in Iga in what is now Mie Prefecture. Even he must have discussed things other than poetry. Maybe he gossiped or complained about people sometimes. What was the conversation like between the pair, as they passed through the long avenue of cedars along the highway that led to Nikko?

While my imagination roamed, I inadvertently nodded off. By the time my eyes opened the train had gone through Kanuma. I half rose in my seat, wondering what to do, but by then we had gone through Imaichi as well. Nikko was rapidly approaching, and I felt utterly incapable of catching another train back to Kanuma, in order to come this far once again by bicycle, so I alighted at Nikko and exited the station.

Nikko is a World Heritage Site, the kind of place everybody goes to for school excursions and family trips. Everybody from the Kanto region comes here, but I grew up in Western Japan, and this was my first visit.

Upon arrival I immediately reassembled my bike at the rotary outside the station. A blue, blue sky was suffused with dazzling, intense light. My first impression was one of pleasure at having arrived at a truly lovely place and it was tempting to sit on a bench and continue my nap, but I roused myself to take a reading in the plant bed on the station plaza. Like Utsunomiya Station, it was also 0.14 microsieverts. Kanuma had recorded 0.05 and thus no radiation detected, which was strange since it was between Nikko and Utsunomiya. I realized then that fallout from the nuclear accident cannot be thought of in terms of straight lines and distances.

JR Nikko Station: 0.14 microsieverts

Venerable, old souvenir shops lined the slope leading up to the Toshogu Shrine. The average reading along there was 0.14. Before long I reached the place where Basho and Sora had stayed a night. Here, too, it was 0.14. In Basho’s day a lodge called Zenkon had offered free accommodation to monks roaming the country on pilgrimages and other refined personages. It’s possible Basho and Sora stayed here gratis, and that may be the reason for Basho’s pointed comments about the innkeeper, who had introduced himself saying, “My name is Buddha Gozaemon.” Basho, who was baffled as to why anybody would introduce himself as a Buddha, was distrustful and wary of the innkeeper’s motives. But he came to the conclusion that, “although he was ignorant and clumsy, he was honesty itself.” (Basho 2017, 27) Free accommodation is, of course, welcome, but when offered in a show of virtue the recipient may not feel the expected gratitude. The old inn district of Hatsuishi is now remembered for this very human exchange, which makes it seem like a font of subtleties and nicety of feeling.

Then it was time for Toshogu Shrine. I parked my bike on the edge of the car park and started up a hill path lined with giant cedars. They cast a welcome shade on the hot slog up.

Tourist numbers had apparently dropped since media reports of radiation hotspots in Nikko. Nevertheless, a considerable crowd was making its way up beneath the shade of the trees. I walked in line with everybody else, and on the way saw several signboards proudly announcing that we were at the same altitude, 634 meters, as Tokyo Sky Tree. I hadn’t realized we were so high up, but since this was a World Heritage Site dedicated to the worship of the incarnation of the shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, I wondered about the need to compare it with a newly built tourist attraction. The radiation level alongside the path was slightly higher here.

Nikko, Toshogu Shrine: 0.19 microsieverts

At ten, I entered Toshogu Shrine. The main shrine and other notable sections were shrouded under canopies due to the 22-year long restoration work in progress. Hence I saw almost nothing of the cream of traditional architecture, beautiful sculptures, and elegant exteriors that this shrine is noted for. All considered, a 2300-yen entrance fee seemed rather stiff.

The crowd streamed in. Perspiration poured down the backs of people waiting in the long queue to enter the main hall. I was embarrassed about my large rucksack and the strain of trying not to hit anybody with it only put me in more of a sweat.

Finally I reached the Sacred Stable, famous for its carving of three wise monkeys: “See nothing, speak nothing, hear nothing.” Though still only morning, the crowd was as thick as a New Year’s market; people milled around, smiling broadly as they pointed their cameras at the carved monkeys. Feeling somewhat awkward, I stood at the back of the crowd and took a reading on the grass near the famous carving. The numbers gradually rose. Since it hardly behooves me to say, speak or hear nothing, here are the readings taken near the three monkeys:

Nikko, Toshogu Shrine, Three Monkeys: 0.19 ~ 0.22 microsieverts

In front of the three monkeys carving at Toshogu Shrine. Image provided by Durian Sukegawa.

Despite having only seen the sections without canopies, I did think that the carvings in Toshogu were indeed magnificent. As was the natural setting surrounding the shrine complex. All combined, it was a perfect match for the glorious blue sky above.

How awe-inspiring!

On the green leaves, the young leaves

The light of the sun.

I shaved off my hair,

And now at Black Hair Mountain

It’s time to change clothes.

– Sora

These breezy poems composed by Sora feel as if the words themselves emit limpid sunlight. I guess that’s the kind of place Nikko is; a place of sunshine, which tourists will keep flocking to despite fears of contamination. But instead of signs crowing about it being the same altitude as Tokyo Sky Tree, a radiation monitoring post might be more useful. The knowledge that this beautiful World Heritage Site had also been affected by fallout might give cause to pause for reflection.

Next I went to see the Yakushido temple, also in the same complex but away from the main shrine, which is known for a painted dragon on the ceiling that apparently roars. I had seen photos in high school textbooks, but the real thing looked modern, almost like an anime picture, despite the passage of time. A priest gave a demonstration with wooden clappers, which he knocked together at different points in the interior. They sounded quite ordinary until he banged them directly beneath the dragon’s head, where they made an extraordinarily loud resounding echo. The effect was almost operatic. Most fascinating.

It was so hot and stifling inside Yakushido that I became soaked in sweat again, so when I got out I washed my face in the fountain at the entrance and drank some of the water. Almost as an afterthought I got out the dosimeter and took a reading at the base of a giant cedar tree next to the fountain. When the numbers began to show, my jaw dropped—it was 0.33 microsieverts. Way above my peace of mind standard. I was just one of many tourists spending only a day or two here, but for anyone working at Toshogu who was here all the time, it meant an annual dose of 2.89 millisieverts. The dragon would not be the only one crying.

Nikko, Yakushido temple, next to cedar tree: 0.33 microsieverts

After visiting the Toshogu and Futarasan shrines, Basho headed for “Rear View Falls,” about two and a half kilometers distant, and climbed the mountain to see them. An old school friend had told me that this waterfall is indeed worth seeing once, and it was with anticipation that I set out pedaling along the uphill road.

Very soon, however, the weather turned bad. No sooner did I notice clouds appearing from behind the mountains, than the sky turned completely dark within minutes. Silver raindrops the size of grapes pelted down, accompanied by bolts of lightning. I took shelter under the eaves of a deserted community hall and waited. But the downpour showed no sign of letting up so I decided to be sensible and make this a meal break. Drenched to the skin, I crossed the road and made my way to a restaurant a little further on, where I had a bowl of rice topped with yuba—dried bean curd skin, a famous Nikko delicacy—and vegetables covered in kudzu sauce. I craved a beer after sweating so much, but that would be illegal, since drinking alcohol and riding a bike is considered drunken driving. Instead, I made do with green tea while I waited for the rain to abate.

It was just under an hour before it let up, and once I again I set off uphill. But then came another bolt of lightning. And it began to rain again. The shower grew in intensity until it was a veritable deluge. This time I took shelter at a closed down supermarket, where I sat on a rotting wooden bench to wait it out. At this point I decided to extract a raincoat from the bottom of my rucksack, but as I stretched out my right hand it brushed against something. And there, lo and behold, was a tatty old plastic umbrella that had clearly been abandoned long ago. I decided to avail myself of its use.

Armed with the old umbrella, I waited until the rain eased off before setting out again. It was still raining as I passed through woods dotted with houses and saw large water storage tanks with Delicious Nikko Water painted on the sides. Then the sky swiftly lightened and it was back to mid-summer weather with the sun beating down on my face. A blanket of steam rising from the road surface made it feel like I was riding through a hot spring. Eventually I arrived at a car park marked with a sign for Rear View Falls. From here on the track was rocky and unsurfaced.

I began my ascent through forest brightly lit by the return of the sun, with the sound of a mountain stream burbling in my ears, and finally arrived at my destination. There it was: a powerful rush of blue-white water from the rain-swollen waterfall, dancing against a background of sunlit forest that cradled it like a bowl. In The Narrow Road to Oku, it is introduced thus: “By crawling into the cave one gets the view of the waterfall from behind that gives it the name of ‘Rear View Falls.’”

In the bedrock surrounding the waterfall was a curved recess. No doubt this is where Basho and Sora chose to seat themselves so they could contemplate the scene until they felt one with it.

For a little while

I’ll shut myself inside the falls—

Summer retreat has begun

Rear View Falls. Image provided by Durian Sukegawa.

Though I felt boorish about doing this in such a place, I pulled the dosimeter out anyway. And then blinked in astonishment. The reading was the highest I’d taken so far: 0.43 microsieverts.

Of course nobody would spend all their time at this waterfall, but the same level of radiation would have fallen over the whole area. This was Tochigi, not Fukushima, more than sixty miles from the reactors that exploded, yet this was the level of contamination … What was the water that ran through this forest used for? Those signs I’d seen on the water storage tanks that read Delicious Nikko Water, suddenly seemed grimly ironic.

I made my way back on the forest track to find an elegant stick insect waiting for me on the handlebars of my bike. In shape it looked almost as if it had been formed by drops of water trickling down from the trees. Being something of an insect fancier I was happy to meet it, but now that I knew about the high level of radiation here, I couldn’t help but think of mutant insects in the Miyazaki Hayao film Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind.

Nikko, Rear View Falls, next to viewing platform: 0.43 microsieverts

It was time to put Nikko behind me and head for Nasu, along a downhill road that required almost no pedaling. The blue sky was back, while foliage and trees all around me still wet from the rain glistened in the sunshine as I passed through a dreamlike panorama of rural scenery. But I was reeling with shock at the discovery of such high level radiation at Rear View Falls—a place I had longed to see ever since first reading The Narrow Road to Oku—and I sensed a shift in my view of things; there was something fundamentally different about my journey now, from what it had been yesterday.

On the outskirts of Kinugawa, a hot spring resort town, pockets of woodland encased in light dotted the serene landscape. I was surprised you could still find places like this in Japan. People fished with decoys for sweetfish from the bridge. A faintly scented wind blew through the rice paddies. The rice was deepening its glow as autumn drew near. How much labor had it taken to create fields as fertile as these? But the numbers on the dosimeter rose. This place had not escaped contamination either. When the farmers shipped their crop, no doubt the rice would undergo stringent inspection and have stiff conditions imposed on its use.

Rice fields in the vicinity of the Kinugawa river: 0.22 microsieverts