Abstract: This Diary written by twentieth-generation sake brewer of Futaba, Tomisawa Shūhei, from March 11, 2011 until April 21, 2011, depicts the experience of his family as they navigated the forced evacuation of their ancestral home as a result of the disastrous nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. The Diary is translated to reflect the original and only occasionally adds names or descriptions for clarity.

Keywords: Sake brewery; Fukushima; radiation; diary; refugee

Twelve years ago, a tightly knit family was evacuated from their sake brewery in Futaba, Japan when the nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear power plant owned by the Tokyo Electric Power Company underwent meltdown. The Tomisawa family had been brewing sake for twenty-one generations—since 1650. On March 12, 2011 they were given no choice but to evacuate with fifteen minutes to pack. The Japanese National Self-Defense Forces told them that they were the last family in the area to be moved out. The family had not been informed of the state of the plant, so their daughter Mari had been outdoors when one of the reactors exploded. She had been checking on neighbors and doing dishes in the front garden, since electricity and water had been cut off as a result of the 3/11 Tohoku earthquake. The nuclear meltdowns have displaced 164,865 people in total. The majority of them will never return home. The impact of losing one’s home and livelihood continues for generations. How raw and devastating the disaster still seems when we look at how far the damage has rippled for the people who once lived there.

Mr. Tomisawa’s hand-written Diary and maps, published here for the first time in any language, provide a glimpse of how life began for one family in the Fukushima diaspora. Most of those who were forced to leave their homes have been called “evacuees,” even though a mere third of the population removed from their homes ever returned. “Evacuee” is a propagandistic term that implies that the evacuation is only temporary. Yet, the Tomisawa family continues to adapt to the consequences of ecological catastrophe caused by radiation poisoning of their brewery and home. The twelve-year struggle to restart their brewery offers a counter-history to the dominant, overly sanguine official narrative of “return.” The most disastrous thing that could happen to the Tomisawas did happen—their centuries-long family legacy was in jeopardy. The mission for the first few years of this family was to return home. The idea of no return, to be cut off from neighbors and a livelihood with a profound 360-year history, was unfathomable. The Tomisawas have grappled for over a decade with the loss of the Futaba family home and business. How can there be but deep resentment toward the corporate nation-state that speaks only in terms of national revival and return?

There yesterday (and for centuries), but gone today is the situation under which Mr. Tomisawa wrote his Diary. It describes in detail the first forty days of the family’s experience as nuclear refugees. I first learned about Mr. Tomisawa through his eldest daughter Mari. I met her at an event held on December 1, 2014 in the main hall of the Kо̄senji temple, hidden among medium size buildings in the suburb of Kichijо̄ji, Tokyo. It was organized by performance artist Ai Kaneko as part of an on-going series “Thinking about Fukushima.” At this fundraiser, Mari presented the plight of her family. Sitting in the large dim hall, I was taken by Mari’s sensitive rendering of her father’s mental and physical state in reaction to the loss of the brewery. Mari generously agreed to talk with my students at University of Minnesota on multiple occasions about her family’s experiences and challenges.

This Diary conveys a personal history that is critical of the dominant national narrative and true to the experiences of so many families set adrift. For the occasion of the publication of her father’s diary, Mari recently sent me these words. They provide a context for the Diary:

Before reading this diary, it might be helpful for readers to know about the Tomisawa family. The Tomisawas moved to where we resided in Futaba around 1189 and began brewing sake in 1650. From then until the nuclear meltdown in 2011, we lived in Futaba for twenty-one generations. Making sake on this land has been my family’s identity and pride. My family consists of my parents Shūhei and Etsuko, my eldest brother Mamoru (b. 1982), my grandmothers, me (b. 1984), my younger sister Eri (b. 1988), and Satoru (b. 1987) who was residing in Hokkaido at the time. Sake has been like a vital family member to my father. On 3/11, in trying to save the Daiginjo brew from heavy equipment radically tipping as the earthquake hit, my father gravely injured his dominant hand. But our sake brewery survived the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake and we aimed to restart brewing of sake within two weeks of the earthquake. Then on March 12, we were hit by the nuclear explosion. We were 3.5 km or less from the nuclear power plant. We experienced a tremendous boom and heard something like sand raining loudly on our roof. Even then, we couldn’t have anticipated that the plant had exploded and our lives would be forever changed. Why did my father endure the pain and bleeding of his hand to stay at the brewery after 3/11? Because it is his life. Then we were told that we had only 15 minutes to evacuate. We left the soul that is Tomisawa Shūhei at that place. After that, my father seemed as if barely alive. My father with his robust back was bent over, small and pitiful. In 2022, my elder brother and I began making sake in Seattle. We would resurrect our clan’s history. My father’s work visa didn’t arrive in time, and he couldn’t make the winter brew. We told him, “There’s next year.” But my father was insistent. He managed to get to the U.S. His insistence that he come to the U.S. to brew, I learned, was because there was a high likelihood that he had cancer. I was shocked and confused, telling him that he needed to give up on the U.S. and go to the doctor! Get medical treatment, then come, I said. He ignored me and Mamoru saying, “Brewing sake is my life. I want to see Shirafuji resurrected. Please understand.” I believe that my father will beat cancer, though I am afraid of what will happen to him. My father is even more afraid. But he chose making sake over medical treatment because the last twelve years of not being able to make sake has felt like dying. Making sake is his hope. With the nuclear meltdown, our house, our memories, our history, our reason for living, our identity, were all lost in an instant. Now my father is energetic. He watches the sake mature every day. This is his only happiness. The anguish and sadness of the early days of forcibly losing his life’s path are written in the Diary. From here on out, my father and family begin a new battle. We will win this battle and carry on brewing Japanese sake in Seattle. The nuclear accident stole everything in one instant. I am grateful to Christine for the opportunity to share these days.

This winter, the Tomisawas completed their first brew in twelve years at the Shirafuji Brewery in Woodinville, Washington. I encourage you to visit their tasting room.

Christine L. Marran

3.11

I spent the morning filtering the Shizuku and Daiginjō brews. In the interior work room, I drew the filtered Daiginjō out from the small tank, finished the brew with micro-filtration, and bottled it. Just after 2:40 pm, a powerful earthquake hit and within seconds, the ground shook so much that it became impossible to stand. The bottles for the Daiginjō that I had just filtered began to topple over, one after another. I instinctively reached out to steady them with my hand. The empty bottles that I had just washed and placed on top of the drying stand behind me began tumbling off one after another and breaking. The two filtration units toppled toward me, and with the drying rack at my back, I was immobilized. I was hemmed in. Then the turbine pump toppled in my direction, cutting off any route of retreat. It was impossible to stand with all of the rocking and shaking of the earthquake. I fell backwards onto the glass that had shattered across the floor.

The kōji culture room door flew open and the light switched on. My son Mamoru stood in front of the door. “Get out of here! You’re in danger!” My voice failed me. Suddenly the pillar holding up the roof of the work room slipped and after a drenching of dust, we saw a patch of blue sky. The water in the cauldron spilled as if it had leapt out of the pot. The small tank holding the Daiginjō had slipped off its pedestal. My feet were in danger of getting crushed. The large refrigeration unit jumped like a frog and nearly fell on me. I will be crushed!, I thought. Eventually the earthquake tremor settled. It had been a long one. My left hand had been severely cut by the broken glass of the bottles. There was a lot of blood! I pressed the cut with the towel I had at my waist. The first thing I needed to do was exit this area. Broken glass pierced my knee-high white galoshes.

The fuel oil tank had toppled and viscous oil was spilling out in a steady stream. I had Mamoru close the stopper. The piled-up sake boxes had tipped and broken bottles were strewn everywhere. The bottling room was a mess. The 300 ml bottles for the unpasteurized sake that I had just washed were broken and scattered about. My left hand continued to bleed profusely. The towel was no longer absorbing, it was so full of blood. The blood flowed into the work area. A piece of glass about three centimeters long was stuck in my left hand. I pulled it out. Mamoru, my wife, and the employees were all okay. I grabbed a dry towel from the clothesline and swapped towels. Roof tiles had fallen. I head to the gate to see what’s transpired. Hanzawa’s place and the Motokendan shop have collapsed. They are damaged beyond repair. I wonder if they are okay. The Tokyo Electronics store, the Hayashi butcher shop, and the stores along the road are leaning precipitously. Ippuku Restaurant owners say their dishes are shattered.

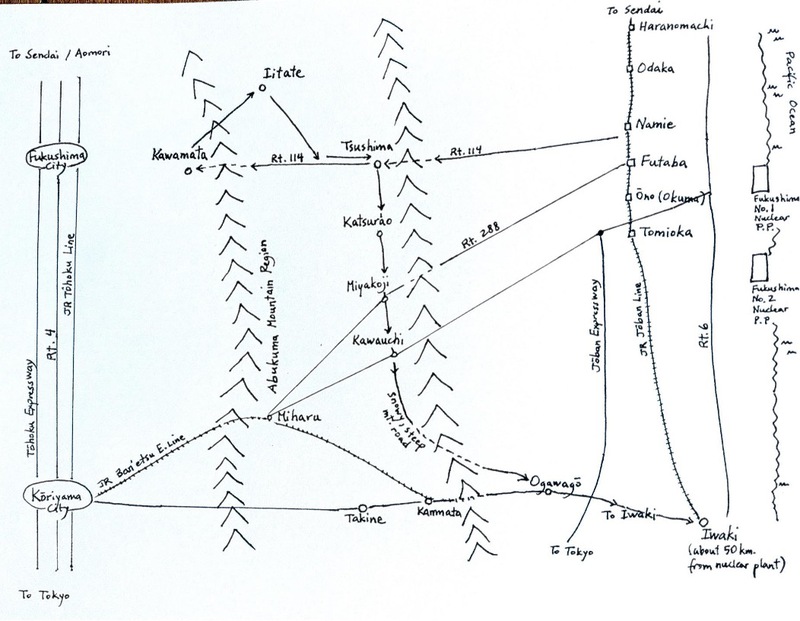

Figure 1: Map of buildings in Futaba.

Worried about my family, I head to the Ishida clinic. The road to get there is strewn with holes and deep fissures in the ground. The earth swells up and undulates like a washboard. It’s dangerous. The houses in town are mangled. Roof tiles are strewn in the road. Hanzawa-san’s house is completely flattened. I’m worried about the Hanzawa family. Motokendan is crushed and looks like it will spill out into the road. Shin-chan and Shūko-san are wearing white helmets with a green stripe that says the name of their general goods store “Motokendan,” carrying a backpack, and wandering about. Shin-chan, in front of his store, spits out the words, “My place is totally ruined.” Fukuchi-san’s house was leaning from the second story, about to collapse. Watanabe-san’s fancy stone warehouse in the Motomachi neighborhood had completely collapsed. Its stones were strewn across the road.

At the Ishida clinic, equipment had been moved into the waiting room. In the middle of this chaos, the doctor kindly took measures to stop the bleeding of my hand. The bleeding just wouldn’t stop, so he put a towel on the wound, told me to hold it there, wrapped dressing around it, and took me to the Public Welfare Hospital. The town I saw from within the car was a mess! Nearly all cement block and rock walls had collapsed. The roads were a mess and roof tiles scattered haphazardly. Nakano-san’s house was completely destroyed. I seem to recall that he was my classmate in middle school. The second story in front of the shrine had completely collapsed and blocked most of the road. We proceeded cautiously in the doctor’s car.

At the Public Welfare Hospital, chairs and beds had been moved out of the hospital and lined up in the front parking lot where they were evacuating patients. Many of them were hooked to IV drips. Physicians in their scrubs were shivering with cold. If they had been in the middle of surgery what would have happened to the patients? Total chaos! Aftershocks continued. This was no time to worry about my hand. Dr. Ishida left to go back. I met with Nishio-san. We talked about the sake brewery. He suggested that since a tsunami is coming, we evacuate to a second story or higher. We take a Gejō district road back. Roof tiles had fallen from all of the homes. Cement block walls had fallen. Pachinko University, a pachinko parlor, looked like it had been sliced in half by a knife. The east side of the building was completely gone. I return home. I take a flashlight from the entryway in the addition [separate house on the property] and go to the brewery. It is completely dark inside. The electricity won’t turn on and the dust is terrible. A couple of the tanks are leaning. They seemed to be disconnected from their foundation. Tanks #1, #2, and #30 are leaning and sake is leaking from them. In the main brewery area, #8 is leaning. The small tank’s plastic cover had flown off and sake was spilling over the rim. The secret brew in the freezer had foundered and the door was ajar. Mamoru said he was going in to examine the rear of the brewery. I told him to be careful. A big aftershock shook our surroundings. Look out! Mamoru and I exited the brewery. We went to the bottling room. Terrible! The bottles that had just been filled with sake were tipped everywhere to the degree that there was nowhere to stand. Many of the bottles were broken. Boxes of sake that had been neatly stacked had toppled and the sake bottles broken. The cartons with six bottles in each were especially damaged. The sake that I had just filtered and my wife had heated, the Shizuku and Daiginjō, were tipped over. The plastic cover of the shochu tank had flown off.

I suddenly realized that all of our efforts and hard work had been ruined. I told Satō-san and Keiko-san to go on home. Because my mother was in a wheelchair in the middle of the room, she was spared. Things had fallen off the shelves, she said. I heard a low echoing sound like the ground or an airplane rumbling “gggooooo.” A tsunami!

The roof tiles of the main house, the addition, and the brewery had fallen to the ground. The interiors were a mess. The brewery’s refrigeration unit had moved and I couldn’t close the door. I got the lift from the bottling house and shifted it, thereby making it possible to close the glass door and the screen door, surprisingly, without any trouble. Yup. It’s the house that grandfather Rishichi built after all. I close the gate.

Mari returned from Namie. We were relieved to find each other in one piece. The town of Namie seems to have incurred more damage than Futaba. The Ueda house is completely ruined, she said. I’m worried about the Ueda family. She said that the road was ripped to shreds and one couldn’t properly pass so she took the old road home. A tremendous number of cars were going from Futaba in the direction of Namie. Because she couldn’t get through the road, she left her Mitsubishi Colt in front of the Hinoya shop, she said.

I tidy the kitchen and generally try to make it usable for daily life. The electricity, plumbing, phones, and cell phones are all inoperative. We have sealed plastic pouch foods that I bought through a connection at the prefectural sake wholesaler and we have rice. We have four cans of oil for heating. But as for water . . . I go to the water tank room and close the waste water valve. We need to be diligent about water use until it’s restored. We use the oil stove for heat and to cook. We boil rice in the iron pot and eat the ready-made curry. We wash dishes using the front garden hose. Our shallow well has become a necessity. We sit around the kotatsu and eat dinner. The electricity is not working, but when we all gather around the kotatsu we somehow manage to stay warm.

An announcement was made that we should evacuate to the Yamada Community Center in Hosoya. There was an announcement that a tsunami was on the way and we should not go toward the ocean. The tsunami would be about three meters high, they said. We brought the car out to the front garden just in case we needed to evacuate. We shoved my winter clothes, like my cotton padded garments and sweaters in the small van, using it like a substitute dresser. But the nights were cold, so I ended up taking my cotton padded clothes out of the van. Our lighting consisted of candles that Mari had purchased previously. At the time, I thought they were an unnecessary purchase, but they sure came in handy at a time like this. My wife brought the small radio she had in the second floor bedroom. This radio was the only means for learning about the situation. They announced evacuation to Futaba Park Hills. Something had happened at the nuclear power plant!

My left hand aches. I take painkillers that a dentist had prescribed me at some point. Aftershocks occur from time to time. It’s hair-raising. I can’t sleep.

3.12

Morning comes. I didn’t sleep at all. It seems the whole family didn’t sleep much. I decide to look around the neighborhood. It’s still early in the morning so no one is around. Still, it seems that everyone has evacuated somewhere. The alley between our house and Wataya-san’s is strewn with countless roof tiles. It’s terrible! The roof of the sales floor has slid about fifty centimeters to the east. The main house is strewn with mountains of tiles and the underlying mortar juts out into the street. It’s dangerous! Has no one been injured? I continue down the alley. The old house that Fumiko lived in has collapsed, Sato-san’s daughter’s new car is damaged. The homes of Ishigami-san, Kiyokawa-san, Kimoto-san, the community center’s Sanpei-san and Serina’s bar, and other buildings to the rear are standing strong—quite different from those on the main road. I wonder if the ground is more firm there. It seems like a lot of people have evacuated to the community center.

Figure 2: Map of the evacuation route.

I eat breakfast. I wait for 8:00 to roll around and head to Ishida clinic to get my left hand looked at. On the way, I see that townspeople have loaded their cars with luggage. Everyone went to an evacuation center at Futaba Middle School apparently. At the evacuation center they were all told to evacuate to Kawamata in their own cars. No one was at the Ishida clinic. The entrance was open but no one was inside. In the waiting room was a cart with medical supplies. There were melted candles and used coffee cups. It looked as if the doctor had been attending to townspeople all night long during the power outage. No one was around. I felt uneasy. When I got home, Ikeshita-san and Tamura-san had loaded their cars with bags. It gets one thinking! Mamoru and Mari went to get the Colt and returned. When we opened the gate, the catch on the gate dented the front of the car. Mari was disheartened.

In the event of an emergency we decided that we should at least evacuate Mamoru. The whole family, with the exception of Mamoru, agreed on this. My wife rode her bicycle to the Town Hall and asked the mayor to take care of Mamoru. Mamoru tearfully complained that he wants to stay here. We all roused ourselves making as if we wanted to chase him off. Mamoru, holding a backpack, cried as he left, saying, “I’ll be back without fail!” I wonder when we will see him next. Might it be a lifetime away? Strange thoughts enter my head. Mari stays with us. She is playing with the cat Eriemon. She seems sad that Mamoru, who is always by her side, has left.

Leftovers from breakfast became our lunch. With Mamoru gone, it feels like a hole has opened up. Around noon, hardly any cars seem to be passing by. There are no announcements. I go to the addition. My wife’s dressers that open facing the east and west have all tipped over. Clothing is scattered everywhere. The bookshelves that face north and south stand as if nothing had ever happened. The books are lined up neatly as always. In my room, my books, papers, and small objects on the shelves are in disarray and I can’t even step in the room. My computer is underneath my wife’s tipped over dresser, which is a total mess. I retrieve my old coin and stamp collection and put it in my shoulder bag.

It’s before 3:00 pm. Mari and I head to the community center at the back side of the house. Hangai-san and our neighbors are there. The television and lights are on. The electricity is on. I guess we have to be a little more patient with regard to our own electricity. The earthquake is being televised. The images give a sense of what happened. I thought it had been more extreme. Hangai-san is being considerate as always. It’s the same Han-chan of the old days. There are elderly men who I’ve not seen in this area. After asking around, I learned that they are folks who don’t own a car, so they went to the Town Hall hoping for transportation to Kawamata. Someone apparently told them, “There is likely someone around who can drive you, so catch a ride with them in their car.” What kind of Town Hall is that!

Is Mamoru okay!?

When I go out to the main road, Self Defense Force vehicles file in from the north. With a blank stare, I watch them pass. The Self Defense Force people stare back at us. I have a strange feeling in my gut.

We have an early dinner of onigiri (rice balls) we received from Hangai-san. Mari went to wash the dishes with the hose in the front garden. Suddenly, we heard an incredibly loud boom! and our house trembled. I wonder if someone’s compressed propane gas cylinder exploded. The cat Eriemon who had been with her immediately responded to the blast with a wail. Mari gathered up the washed dishes and ran into the house. Now Eriemon is her usual self, playing with Mari at the entrance to the kitchen.

A bit after 6:00, I go to the outdoor toilet. Mari for some reason went to the community center behind our home. “Is anyone there?!” I hear Mari’s voice get louder. I go out to the gate. Mari says that no one is at the community center or in the neighborhood. It looks like we’ve been left, she says. “Make preparations for leaving the house!,” she shouts and heads toward Willow Street. I tell my wife to hurry up! We head toward the addition. Eriemon’s new cat companion, Nezucchi, arrives. I pass them in my rush. Nezucchi seemed surprised, but doesn’t move an inch, only staring at me. Grabbing a flashlight, I rush to the second floor of the addition, and take the large backpack I received from my uncle Kōji out of the closet and stuff nearby clothes into it. The Self Defense Force people come to the house. Mari had apparently hailed them over. They see my left hand and remark that the bleeding seems to have stopped. They direct us to get in the car immediately and leave Futaba. The Daiichi nuclear power plant core has melted down and it’s an extremely dangerous situation. Cesium is escaping, we are told. It was then that I knew we would need to leave our land behind. The Self Defense Force people said that this is their last patrol. They said that after forty minutes’ time, Futaba would be closed. They said that we were the last group to evacuate.

We laid the back seats of the van flat and the Self Defense Force folks gently brought my mother out and laid her on some blankets we had spread out in the back of the vehicle. We packed clothes, towels, and my mother’s wheelchair in the empty spaces around her. In Mari’s Colt, we shoved in bath towels, clothes at hand, my backpack, and Mari’s shoulder bag that has her camera collection from one side of the car. We pressed our palms together in prayer at the family shrine and Buddhist altar. It felt unpardonable to leave our house. My chest tightened with deep remorse at having to leave our home. As I got in the car, the image of what had already become a silhouette of the brewery was burned in my retina. My wife closed the door of the bottling cellar–she closed that heavy door with just her strength alone. Mari, crying, gave all the cat food we had to the three cats. Eriemon and Rodem sat side-by-side, like close friends, in front of the western room. Behind them, in front of the entrance to the addition, Nezucchi sat in exactly the same fashion. The three of them saw us off. What a strange threesome. They don’t seem like cats. Mari is crying. “I’m so sorry,” she repeats.

We head toward the Sendan elderly care facility as instructed. The streets have no lights. It’s pitch black. How unnerving! On top of being covered in debris, the road is bumpy and filled with holes and fissures. I wonder if the tires will be okay. The Sendan building has lights on. It’s the base for the Self Defense Forces. Riding from Shirakawa to Natori, we ended up with an elderly man in a mini car and two cars of workers from Sendan. Including us, there are a total of five civilian cars. There are six or seven bedridden elderly folks at Sendan. They are on standby, prostrate in their beds. Apparently they are waiting for vehicles to transport them.

I forgot various important things in the house. I want to go back for them. Realizing that we have no water, I talk with the Self Defense Forces. They divvy up the water they have in their shoulder bags. A large bus-like armored vehicle arrives. The rear end of it opens and the elderly of Sendan are settled inside, bed by bed. It’s finally time to depart! At the head is a small armored vehicle, and then the large armored vehicle with the elderly. The line of cars includes the Sendan workers’ cars, our van that my wife is driving, the car of a female staff member of Sendan, the Colt with me and Mari, the mini car of the elderly gentleman from Shirakawa, and vehicles belonging to the Self Defense Forces. The female staff member of Sendan who was in front of us drove badly, dropped one of her front wheels in a hole and got a flat. A Self Defense Force person efficiently changes out a spare. We enter Rt. 6. It’s unbelievably bumpy and pitted with holes. The bridge and roads are at ridiculously different levels. Using lumber, we somehow manage to make progress. The road is like a washboard with massive indentations and deep fissures. If we didn’t follow the path of the Self Defense Force vehicles, we would be in real trouble.

From the Nakata area, we got on the old road. The Kōnokusa district was in an awful state. The elegantly tiled roof of Idogawa-san’s house had collapsed. The old homes with large roofs were utterly destroyed. Cement block walls had nearly all crumbled. Kōzaki-san’s house and Keiko-san’s house seemed to be fine. I wondered where they had evacuated to. Because she was using a spare tire, the female staff member of Sendan in front of us could not increase her speed. The tail light of the van my wife is driving is gradually coming loose. Right around the time we pass through Namie, I can no longer see her tail lights. We pass through the О̄gaki region and the bad state of the road decreases. Mari’s Soft Bank cell phone works. Docomo does not. That’s when we first learn that soon after we evacuated Futaba, there were aftershocks directly under Futaba. Futaba is…? …Kitties! We are sorry!

We arrive in Tsushima. It’s a confused mess of cars of people who evacuated from all over the area. What a huge number of cars! Our van and the lead armored vehicle are not here and we can’t seem to reach them. Available information seems to suggest that they have gone in the direction of Haramachi. Oh no! I wonder if they are okay. We leave the vicinity of Tsushima. The lead military vehicle heads for Kawamata town. We drive for a while and then Mari tells me to look behind us. I will never forget the endless string of headlights on the mountain road of Rt. 114! We reach Kawamata town. Terrible traffic. We cannot move forward. We reach the station. With so many cars, there is no place to park. We look, but can’t find our van. We find a gas station that’s open and get gas. They won’t sell us more than 20 liters. A Skyline GTR forcibly cuts in line despite the fact that everyone is lining up! They tell us there’s no high octane for sale. We return to the station. I ask the lead Self Defense Force, #6 division, #44 ordinary division about my wife and mother. They say that my mother has been placed in the medical room of the Kawamata elementary school. Mamoru appears to be at the Iizaka elementary school. We go to the Kawamata elementary school and my mother is resting on a bed in the medical room. The heat is on. My wife is not there. We get in the car once more and look through the evacuation centers. We only look in two. The Red Cross had placed a station at the Iizaka elementary school. I had them look at my left hand. I was told there was nothing further they could do. They gave me pain meds. We had nothing else to do but return to the Kawamata elementary school. There’s nowhere for us. Mari and I put five cushions that we’d brought along with us down on the floor in the hallway and lay down. It’s cold and my left hand aches. Earlier, I saw that the digital thermometer in the room read -6. The guys passing through the hall kicked us. What are you doing!? We are Futaba residents just like you! I went into the medical room where my mother was and dozed off. Idogawa-san of Kōnokusa called out to us. They will put us in a large room. It’s warm. Somehow he saved us five cushions’ worth of space. Mari and I slept a bit.

3.13

My wife arrived in the morning. She’s wearing my cold weather gear. She went looking for us and had spent the night in the parking lot of the Kawamata high school. The winter weather gear is thick, but she said it was too cold to sleep. Now she’s sleeping on the cushions as if she were dead. My mother is doing well. She’s staying calm for us. There’s an announcement that onigiri (rice balls) will be handed out for breakfast. A Kawamata evacuation handwritten list of names is taped to the wall and glass. I look for Mamoru. He’s nowhere to be found. Somebody is talking about the earthquake that occurred at the Futaba healthcare facility. The needle of the machine that measures up to 7 swung completely off the chart. It had been a huge earthquake.

Mari and my wife left saying they wanted to refuel the van. The morning meal of onigiri and bread commences. I line up. The townspeople are looking at me as if they are seeing some rare creature. I heard a voice saying “It’s the sake brewer!” “It’s Shūhei!” There were guys pointing at me. What’s going on!? The one who brought the nuclear plant was Tanaka Seitarō! Didn’t everyone treat Tanaka as if he were a god?!

I got in line and met Wataya-san’s family and the family of kendo instructor Honda. These people were decent. I received enough bread for a few people and a breakfast roll for my mother. She ate it with relish. I ran into high school classmate Kanno. He was living in Odaka, but knowing the nuclear plant was in danger, evacuated immediately. He brought his father who had the same degree of dementia as my mother. He and his wife are doing the best they can. It’s really hard. What are those folks dealing with elderly with dementia going to do from here on out? At this evacuation center, the earliest to evacuate secured the best spot and most space. Those people have meticulously prepared. When did they get the announcement to evacuate? There are a few people wearing the uniform of Tokyo Electric employees. Every one of them is covering their name with duct tape to hide it. These guys escaped before anyone else!

Mari and my wife have yet to return. The National Diet member Yoshida Izumi arrives. He explains the situation, and lines up some figures. Somebody asserts in a forceful tone, “Instead of talking about some random data, we want to know if we can return!” Yoshida Izumi-san was at a loss for words!

Mari and my wife return close to lunchtime. In order to put gasoline in the car, they had to go quite far. Finally they were able to get 3000 yen worth. One liter is 170 yen, they said. The gas stations are taking advantage of the situation. Shortly thereafter, the distribution of lunch begins and we line up again. Just as with breakfast, I seem to be an object of scorn. The newspaper was delivered and that’s when I first learn that reactor no. 1 had exploded. That was the explosive sound I heard yesterday! They say that iodine was handed out only to small children. I want Mari at least to get iodine. There should at least have been enough at the Town Hall for everyone in the town to get iodine! What happened?

Town council member Kowata-san stepped in to manage things. The workers at the Town Hall just sat around in chairs, arrogant and unhelpful. The son of Yamamoto-san, Kazuya-kun, was typical, despite the fact that his father had worked with us for decades. When I had time, I checked the bulletin board, and searched for Mamoru’s whereabouts. Mamoru’s name was nowhere to be found at any of the evacuation centers. I asked the staff for help and they blew me off telling me to look at the bulletin board. How can I get a map of Kawamata town? I take Mari’s car and go to every evacuation center in Kawamata. There’s a fair amount of difference among the evacuation centers. At every one of the evacuation centers is a council member in charge, taking the lead. The staff mechanically respond with no warmth or sympathy. I search each and every evacuation center, but Mamoru is nowhere to be found.

When I return, there is a problem with my mother. She only woke once during the night, yet they claim that because she talked to someone, she had made a “big fuss.” The elderly of Sendan brought a lot of snacks and she wanted some. The woman in charge said that they would take care of the Sendan elderly as part of their job, but they wouldn’t take care of my mother who was not with Sendan. My family was told either to have someone accompany her all day long or go to a different evacuation center. There weren’t many adult diapers left. Kawamata stores were mostly closed and even if they were open, there was almost nothing for sale. We asked Sendan to share adult diapers, but were refused. Mari’s Soft Bank cell phone connected and my wife’s elder brother Mitsuyo said he could come help. Mamoru seems to have been left with О̄kuma’s town’s evacuation team. Futaba town’s lack of responsibility and unreliable information piss me off!

We decided to leave this evacuation center and go to my wife’s childhood home in Iwaki. We told Idogawa-san, who had helped us with our plans, and thanked him. Fools near us grumbled in a loud voice that we’re lucky to be going to the Hachiman shrine. I’m getting increasingly sick of the Futaba people. I put water into an empty plastic water bottle. I have the precious onigiri that I saved from lunch and a few pieces of candy that Mamoru’s kendo student gave me. This is all I have for food! We put my mother in the van just like we had prior to arriving here. Idogawa-san saw us off throughout the process. We left the evacuation center as dusk was falling.

We connected with my youngest daughter Eri using Mari’s cell phone! It worked! Eri became the head contact and related my younger brother Fumio’s instructions. They said to follow Rt. 399 as the other roads were blocked. I’ve taken Rt. 399 from Kawauchi to Iwaki a couple of times, but it is an awful mountain pass along a deep valley. The road is narrow with a continuous precipitous incline. Right now it’s likely covered in snow. Oh god! We head to Iitate and then get on Rt. 399 from there. Here it is a mountain pass, but it is paved and has some width to it. I am envious of the light shining from people’s homes along the road. We get on Rt. 114 and dip down to Tsushima. There’s a checkpoint. We turn toward Katsurao before reaching it. In Katsurao, they are all living as if nothing has happened. We pass through Katsurao. We get on Rt. 288 and head toward the town of Miyakoji. Maybe Mamoru is there. We go to the elementary school thinking that it may have been turned into an evacuation center. It’s pitch black! No one is there! We go to Miyakoji Town Hall. It’s closed.

It appears that Miyakoji moved to Funehiki. We head toward Kawauchi. Kawauchi village is normal! There’s a light on at Komatsu-ya. They are living normally. I’m envious. There are vehicles that appear to belong to the Self Defense Forces in the Kawauchi village town hall. Kawauchi is in the Futaba district and not that far from the nuclear power plant. I wonder how long they can stay like this. At a lower Kawauchi traffic light, we turn 90-degrees toward Iwaki. The van is not following us. I stay at the traffic light while Mari goes to look for them. Shortly thereafter, they showed up. My mother had thrown up. She’s always gotten car sick. I’m worried about the severe mountain road we are about to take! With all of us together, we split the single onigiri and candy. Worried about my mother, I decide to ride in the passenger’s seat. We’re off! Just as we are plugging along, Mari takes the wrong road. I should have ridden in the Colt. From here on out, we are on a perilous mountain road! The snow becomes conspicuous on the road. The incline becomes increasingly steep with endless sharp curves. The road is no longer paved. The Colt has studless winter tires but the van has worn-down summer tires. Finally, the van slips in the snow and gets stuck. I change places with my wife and drive, wondering if my left hand will be okay. Somehow we make progress through the steep snowy road. My left hand hurts. I cannot use it. I grip the steering wheel with my one hand. Somehow we inch forward on the steep snowy road, but we couldn’t even brake on the downhill. I cannot control the car. If the wheel comes off the axel we are done. We will spin. Somehow let us be safe!

We progress slowly in second gear. I recognize the beauty of an automatic. I haven’t slept for two days, but the pain of my left hand keeps me driving. What a joke! My mother vomits. When she gets sick, we stop the car and wipe her mouth with a bath towel. At one point, she grabs my sleeve and cries, “I won’t resent you for it so please, abandon me here! Let me off here!” This isn’t the dementia speaking! She’s sane! The cold is relentless. It’s below freezing. If we get stuck here, it’s the end! Through the mountain pass, we could see the lights of Iwaki in the distance. We finally made it. What joy! The snow begins to disappear, the road is better maintained, and the curves more gentle. My mother vomits again. As we are taking care of her, a car passes us. It’s all good as long as Mari doesn’t mistake that car for us.

The sign for “Ogawagō” station! We made it! Just a bit further! We slip out of the mountains and exit onto open land. We head straight for town. On the way, we pass a car with the brights on. Is that Mari’s Colt?! Did she turn around to look for us? We decide to continue on. We arrive at Hachiman shrine. The Colt is not there. We go to my wife’s childhood home, Takatsuki. It’s pitch black and no one seems to be around. We return to the Hachiman shrine. Mitsuyo-san’s family comes out to greet us. “Get in the bath immediately,” they tell us, and we are sent to the back door area. We are told to undress completely outside the back door. They tell us to put the clothes we’ve removed into the nearby plastic bags. I feel miserable. Under my pantlegs are countless bloodstains! It appears that there are myriad tiny shards of glass sticking in my pants. I get in the bath. It’s been a long time since I’ve had one and it feels amazing! In the midst of my bath I learn that Mari and my wife have arrived. Mari and my wife take their turn. They strip down completely and get in the bath. The Mitsuyos had prepared food, a room, and toiletries. I watch television. A huge tsunami had attacked nuclear plants one and two! I can’t believe it. No one told us this in either Futaba or Kawamata. Mari and my wife help my mother bathe. My mother is making a huge fuss. We all eat rice porridge together. It’s delicious! Tonight I will sleep in a warm room on a futon. This may be nothing but normal, but it’s pure joy. I’m grateful to Mitsuyo’s family for their generosity. My first deep sleep in a while!

3.14

Mitsuyo-san managed to get water, and washed the Colt and van to remove any radiation. Iwaki has shut off the water, so I imagine that it was hard to procure this water. What about yesterday’s bath water? I am filled with gratitude. All of our things including our clothes, our shoes, everything on us, the clothes we brought, the cushions, were all disposed of. What a pitiful feeling! Discreetly, I put aside my collections in the shoulder bag and Mari’s camera. Breakfast was yesterday’s leftover porridge. We polished it off. Knowing the pitiful feeling of having no food means one can’t tolerate wasting a morsel. Mitsuyo-san searches for a clinic to check our radiation levels and examine my left hand. The Fukushima Workers’ Hospital. Everyone gets in the van and we head to the Fukushima Workers’ Hospital. We enter the main entrance, and upon explaining our situation at the front desk, we are abruptly sent outside and taken around the back of the building. We are let in through a narrow entrance between halls. Inside, the room is covered in pink plastic. The person examining us is wearing protective gear and looks scary! We are being treated like a patient with a contagious disease. There was a similar scene in a movie I saw as a student. I had endured very little exposure. The bandage on my left hand had the most with 1.8. It was a blessing that I had been in the house during the explosion and had immediately bathed yesterday. My wife, who hadn’t washed her hair, had modestly higher levels. Those who had been standing in the field of the Futaba High School waiting for the helicopter apparently experienced severe levels of radiation.

They proceeded to perform surgery on my left hand. My physician was the vice head of the hospital, Dr. Iwai. Even with an anesthetic, the surgery hurt. Apparently there were still shards of glass in my wound. I was told that I’d really endured a lot with this wound for the past three days. Still, there was nothing I could do but put up with it. With the surgery complete, I left the clinic. For the first time in a long while, I could stretch out the fingers of my left hand. Everyone had been in the van waiting for me. Mari had gotten hold of iodine that she was unable to get in Kawamata. There should have been a ton of iodine at Futaba Town Hall. Why wasn’t there any!? Mamoru has been found. My brother Masayuki seems to have called one evacuation center after another and found him. They said he was in Takine city. All evacuation of regular citizens appears to have been left to the О̄kuma city evacuation team. Those awful Futaba Town Hall creeps!

I call Fumio. Suddenly I regret abandoning the Tomisawa home. Tears stream from my eyes.

I’m told, “Where there is life, there is hope.”

Everyone eats a pastry in the car. It’s tasty. We return to the shrine. We hear from Mitsuyo that we are to leave Iwaki. Apparently it is not beyond the realm of possibility that reactors no. 1 through no. 4 at the Daiichi nuclear power plant are capable of a meltdown. It seems to me that the meltdown is already happening. If the entire Daiichi plant is ruined, it won’t be anything resembling Chernobyl that lost only one reactor. I reach my cousin Kumiko-chan and Masayuki. I cry again for having abandoned the Tomisawa home. Everyone comforts me. I need to get my emotions under control!

3.15

I hear that the previous night’s guard is a difficult person. I was relieved that it was a night without incident. On the morning news, we learn that the Daiichi nuclear power plant is in a dangerous state and no one knows what will happen. I walk to the Workers’ Hospital. The York Benimaru Supermarket on the way to the hospital is not open yet, but a large crowd of people is lining up. Dr. Iwai examined my left hand. I was told that the muscle tissue had been severed and the pinkie and ring finger will likely be permanently damaged. Likely I won’t be able to use my left hand like I used to. I’m lucky just to have saved the fingers. Once the wound heals, I should do rehabilitation therapy.

I walk back. The 7-11 store on the way back says that it will close mid-morning. I go in but there’s no food left in the store. I buy nail clippers for now and return to the shrine. We finally reach my younger son Satoru by phone. He says that we will probably die of radiation from the nuclear accident. ‘We can’t be saved’, he says. Satoru is crying on the other side of the phone line. I told him to decide whether he would fly back to Tokyo [from college in Hokkaido] tomorrow.

Iwaki also seems to be in danger. Mitsuyo’s family will apparently evacuate to Tokyo. They ask me about what transpired at the Kawamata evacuation center. They say that they will close up the Hachiman-sama shrine. We pack our bags mid-morning and put them in the two cars and move to Takatsuki. We put my mother in the wheelchair and I push her, taking her with us. We will live in the new house in Takatsuki that my wife’s elder brother Mitsumasa and his wife prepared for my mother-in-law, Grandmother Taira. Mitsuyo-san came over. He tells me that they rented an apartment in Koganei [in Tokyo]. He hands me the keys for the house and car. “We’ve purchased various things for the house so please use them,” he says. My family loaded up the two cars and took off. As we were getting into the car, Mitsuyo’s daughter Yasuko-chan put their cat in a carrier and brought it to their car. Mari watched enviously. After we set out, she began crying. I wonder how the cats we left in Futaba are faring.

We use the bath at Mitsumasa’s and then head back for dinner. Mitsuyo’s other daughter Tomoko-chan arrives. She is apparently surprised to see us. It seems like she has something she wants to say, but she’s not clear. She rambles for a while, then leaves. My mother seems calm for the first time in a long while. We lay her down in Grandmother Taira’s bed. My wife sleeps in the bed of our family’s long-term caretaker Watanabe-san. Mari sleeps on the chaise in the living room and I lay a futon on the floor in the living room and sleep there. Mari uses the laptop computer to put our story of evacuation from Futaba on Twitter. She got a huge response.

3.16

Hosing down of the nuclear plant continues. I bow my head in nothing but respect for the Self Defense soldiers risking their lives to do this dangerous work. Mari and I connect a hose from the garden spigot to the bath. Mitsumasa had told me that the pump’s motor won’t take continuous running of water in the bath. At the new house, Mitsumasa came over to tell us about the new elderly care home they are opening. My wife is enthusiastic about it. I have no right to resist. I have no choice but to go along with everyone’s opinion—the whole family would work at the care home. But having my children take care of other elderlies’ diaper changes, I’m not sure about that. The van is out of gas, but all gas stations are closed and we can’t manage to find any gasoline. We try to siphon gas from Mitsuyo and A-chan’s car to no avail. Mari received an email from a western Japan brewer Hanaharu’s president Miyamori. He was worried and had been looking for us. He writes, “Don’t think twice about it! Come to Aizu. Let’s make Shirafuji sake together.” I shed tears. But I’m not sure what to do. I feel a ray of hope. Newspaper companies and publishers who saw the Twitter tweets that Mari posted about our evacuation want to receive permission to use them. Mari gives the okay.

3.17

My wife got overly excited by Mitsumasa’s idea and is going full speed ahead with it. She’s telling Mari, “Do this! Do that!,” ordering her around. Mari’s finally had enough. I’ve had the feeling for a while that my wife is overdoing it. Mari says she is returning to Futaba. I’m going back too. Everything I am and everything I have is in Futaba. To my wife, where we are now is a place to return to, but to us Futaba is the place to return to! I’m not afraid of dying! Finally, my wife gives in.

The Fukushima Workers hospital suspended their outpatient care. There’s nothing to do but go back to the house. Mari gets in the car. On the way back, we follow the Self Defense Force vehicles. The army trucks are from Nerima and have massive spring suspension making them not your everyday truck. Without this kind of vehicle, you can’t get to the nuclear plant? What’s going on with the nuclear power plant?! I’m furious at not being apprised of anything! But I bow my head and have nothing but respect for the Self Defense Force people who are risking their lives in going to the nuclear power plant.

The water is still shut off. Because water is available at a park on our way to the Fukushima Workers Hospital, there was a line of people with plastic water bottles and poly tanks. The Wakamatsu Noodle shop left an artisanal well (with a natural spring) open for public use and every day a long, snake-like line of people queued up for water. I now realize the inconvenience of having no running water, especially when we have to go to the toilet. Watanabe-san came over as we were having dinner. He was surprised to see us. I tell him to head over to Mitsumasa’s. The two men seem to be in discussion over something. After a bit, Mitsumasa-san comes over to ask us if we have any gasoline. How would we possibly have any gasoline! Watanabe-san came over and yelled at my wife, “You and the head priest are the worst!,” and left. I wonder what Mitsumasa-san said to him.

3.18

We make contact with Mamoru. He is at the gymnasium in Takine town, which is the evacuation center for О̄kuma Town. We are in “Kammata” so it’s not too far. They say that tomorrow Mamoru will move to Saitama through Kawamata. Mari will go pick him up. Finally we will meet up with Mamoru. At the evacuation center, Mamoru was bossed around by a previous city council member Ogata. When Mari located Mamoru in the gymnasium, you could see sadness in his eyes. He looked pitiful. We are all finally together. At dinnertime, we all raise a glass with beer we brought from Mitsuyo-san’s house.

According to Mamoru, Ogawa wants to leverage reactors no. 5 and no. 6 [currently not in use] at the Daiichi nuclear power plant in negotiating a deal with Tokyo Electric. He argued that the reactors in neighboring О̄kuma are all kaput, so now it is the era of Futaba. Idiot! Moron! When I consider that this kind of guy was a candidate for mayor, I’m embarrassed at our town’s low standards.

The top part of the reactor has a boric acid tank, and in the worst case scenario, it could be blown up to stop the nuclear reactor, they say. But they also say that if you do that, the nuclear reactor will be ruined. This accident became serious because Tokyo Electric didn’t follow through on that. They didn’t consider this to be a consequential accident, so their intention has been to save the nuclear reactor for use again. This is all the fault of the main company in Tokyo!

In Iwaki, all of the gas stations have closed, and the number of cars on the road have decreased to only a very few. When Mari went to get Mamoru, the gasoline stations in Takine were all open for business as usual, and there was no sense of a gasoline shortage. Luckily we were able to fill the tank of the Colt. I had heard that the entire prefecture has a low gasoline supply, but maybe it was only Iwaki.

3.19

The wound on my left hand appears infected. It has an odor to it. Mari calls the Fukushima Workers Hospital for me. We enter through the emergency entrance. Bacteria has infected the wound. It was fixed with one more stitch. They tell me that I had gotten thirteen stitches already. The Fukushima Worker’s Hospital is closed because the water has been cut off. The hospital is only open for emergencies. Someone who has injured their right hand is in the waiting room. It is a volunteer who was cleaning up debris at an emergency soup kitchen when debris collapsed and injured their hand. I take my hat off to them for their volunteerism.

The traffic in the city of Iwaki is sparse. It’s practically a ghost town. Goods distribution is not functioning. All stores are closed. I feel keenly how important distribution is. I cannot believe what Mari told me about gasoline in Takine. What’s going on? The cars are on empty. The Colt got refilled at Takine, but we need to use it wisely. We will use Grandmother Taira and A-chan’s cars. We go to the hospital where Grandmother Taira is hospitalized and I stay with her until evening. It sounds like she fired Watanabe-san the day before yesterday. It’s going to get hard from here.

I’m finally free of attendance duty in the evening. I hadn’t had lunch and was starving. Next time I’ll have to bring food with me. My wife stays with her in the evenings. The entire family will have to join forces. Mitsumasa and his wife returned home.

I went to check on the family graves. The gravestones have toppled over. I pray at Grandfather Taira’s grave. I go up the mountain to look for a spring that is said to be on the side of the hill, but can’t find it. Maybe it was buried underneath the garbage that had been dumped there by someone from above.

3.20

Fumio arrives. Just like always, I head to the Fukushima Workers Hospital to get my hand examined for how well it is healing. After returning to Takatsuki, I walk to Hachiman shrine and pray at the closed gate. Just as I pass through the torii gate, Fumio’s Volkswagen arrives. I get a lift, and he shows me around Takatsuki. He brought various items for us. It must have been difficult to collect this much stuff. I was especially grateful for the food and clothes. There were goods from Eri. So helpful! Fumio says he doesn’t have enough gas. We tried to siphon some from Mitsuyo-san’s car but it didn’t work. He left for home immediately. Sorry for the trouble! Thanks!

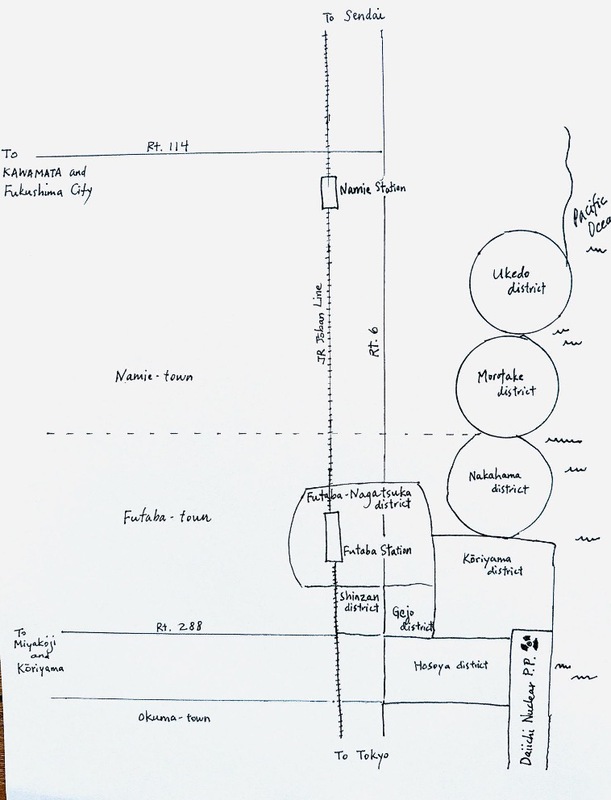

Figure 3: Map of districts.

According to Fumio, not much about the situation at the Fukushima nuclear power plant had been reported in Tokyo. The fact that things were happening with the plutonium thermal at reactor no. 3 was not reported at all. Did they consider at all the horrors of that black mushroom cloud when reactor no. 3 exploded?! The half-life of plutonium is 25,000 years! Tokyo Electric knows that and has reported nothing. And it’s not just the government and Tokyo Electric. The mass media is a problem too! About 20 years ago, I was asked by a classmate working at the Town Hall to be the “Nuclear power public relations committee member” for Futaba. One time, during a committee meeting, I asked the contact for Tokyo Electric a question about the “decommissioning” of the first reactor of Daiichi nuclear power plant after it had been running straight for twenty years. I had read somewhere in some book that the standard life-span of a nuclear reactor is thirty years. The response from Tokyo Electric was extremely vague with them essentially saying it will be fine for some time yet. On the way home, I was warned by a town council member “not to ask Tokyo Electric any further questions about decommissioning from here on out.” We are about to pass the forty-year mark for reactor no. 1. Before the earthquake disaster, Tokyo Electric had submitted a document that said the reactor had twenty more years and they’d use it for sixty years, which was approved. What is the use of a Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency?! According to Fumio, the head jerk of NISA, Madarame, is pretty high up among the pro-nuclear power faction. These kind of jerks are managing nuclear safety!

3.22

Masayuki arrives. He rented a microbus with Mieko. They kindly invited us to go to Tokyo with them. I declined though I was grateful that they’d made such a kind offer. They brought the newspapers and weekly magazines I requested. I couldn’t get any weekly magazines in Iwaki. Now I know all about the nuclear accident, the earthquake, and the tsunami. Now I understand Prime Minister Kan and Tokyo Electric’s total dereliction of duty. What’s going on with today’s Japan!

Gasoline finally arrived in Iwaki city and the gas stations will soon offer gas, but the traffic is light and it feels like a ghost town. Still, what about when Mari went to pick up Mamoru and got gasoline in Takine? Mari’s friend from Takine who came over the other day also found Iwaki’s lack of gasoline surprising. Maybe Takine is an anomaly.

Rumors about radiation in Fukushima prefecture spread and our reputation drops precipitously. Radiation is being detected in dairy products. They say Fukushima products won’t ship. Even if we could restart the brewery, could we make it work, I wonder?

3.24

I go to the Fukushima Worker’s Hospital. It has returned to its normal state. Dr. Iwai who operated on my hand took a look at it. They will remove the stitches on the 28th (Monday). On the way home, the local York Benimaru store was open so I checked it out. So many people! They had an abundance of merchandise, but not a single Cup of Instant Noodles. Fruits and vegetables were abundant. It felt like everything had returned to normal. Just like yesterday, at 11:30 I head to the Matsumura Hospital to attend to my mother-in-law. In front of the Matsumura Hospital is a group of people wearing helmets that say, “Yokohama ##”. It looks like they are handling emergencies. The entrance is open and there are people in the lobby. Until yesterday, the lights were off, the doors locked, and baggage piled everywhere. It was like being in a car garage. On the fifth-floor ward, there were hardly any patients, but today elderly people are transported in one after another and the rooms are full. Did they come here after returning to their homes or were they brought from a different hospital? In any case, this hospital seems to have returned to normal.

4.3

Yesterday, Mamoru and Mari put gas in the van. This morning, they say they are heading to Kо̄riyama. Weird! Why are they taking the van instead of the Colt? Why are the two of them wearing rags? Mari has no make-up on. I bet it’s to break into the secured area of Futaba. I tried to stop them, but they took off. I called their cell phones multiple times, but they didn’t pick up. I sat there worrying as I attended to my mother-in-law at the Matsumura Hospital. I went home early. Mamoru and Mari were back. Heading into the living room, I saw that they’d tried to hide the brewery sign and sake trophies behind the sofa. I scolded them harshly: “Don’t do that again!” But there was another self that thought, regretfully, you beat me to it.

4.4

When I return from attending my mother-in-law, nobody is home. The family had taken my mother to the hospital. It’s true that since the earthquake, she had not been receiving the medical care of Dr. Ishida. She needs a new attending physician in the area. It was decided that she should see the attending general practitioner. My wife and I waited while they examined her. It appears that my mother’s symptoms closely resemble my mother-in-law’s when her legs started getting worse. She also has a cold. They prescribed medicine. Mamoru was also under the weather and given meds. Because we are victims of a disaster, there was no charge. I decide to go in myself tomorrow.

4.5

I go to the Shimizu clinic. My blurred eyesight and sense of looking through a white haze is caused by exhaustion and stress apparently. We talk as a family and decide to break into Futaba tomorrow. We make a list of all the things to grab from the Futaba house. My heart is racing! Even though I’m just returning to my own home, I can’t sleep a wink tonight.

4.6

Today is the day we carry out our plan to storm Futaba! At 5:45 am, Mitsumasa-san leaves for the shrine. We have a simple breakfast and all pile into the van. We’re off in sunny, clear weather! We head to Rt. 399. A month earlier we took this road, risking our lives. On the way, we are greeted by a barricade, but it is in a diagonal position so that cars can pass through it. It seems that there were others who had entered before us. We pass some cars going in the opposite direction. Everyone is wearing a mask. Fellow trespassers!

We go from Kawauchi to Miyakoji and then from there toward Katsurao. We are retracing our evacuation route of one month ago. From Katsurao, we take a road through О̄gaki. On the way, we put on raincoats inside the car and double up on masks. We enter Namie. We take an old road toward Futaba. The connection to the bridge in front of Yokoyama clinic is so bad (not level) that we cannot cross. We turn back and get on Rt. 6 and go into town on the front road of the train station. There are so many stray dogs! They must have homes nearby. The town looks much worse than the day we evacuated. We arrive at our house! Mamoru goes through the hidden entrance and opens the gate [from the inside]. We go inside. I am surprised that it looks just as we left it. Amazing! I offer a prayer at our home shrine and to the ancestors. I go to the brewery office. I take the computer, software CDs, brewery license and one of our two most treasured company calligraphy scrolls–the Tenshin scroll– to the car. I move my father’s valuables and small camphor chest containing his keepsakes to the car. I get the authorization licenses and proof of insurance from the safe. Mamoru says he will get three scrolls from our western-style guest room and put them in the car. I go to the addition. I collect the samples of past shochu and undiluted sake that had been left in the hallway. I head to my room. My dresser is tipped over and a mess. There’s nowhere to step. One by one, I put my computer software, notebooks related to the brewery, notebooks on the area’s land, money, computer, and bank books into a large shopping bag and head to the car. I gather up my work-related computer on the second floor. I put gasoline that we had in a steel container in the van. Mamoru and my wife put sake from the bottling room into the van. I take other shopping bags up to the second floor of the addition and choose some clothes to stuff in them. When I take them to the mini van, it’s already full, mostly with Mari’s clothes. We shove clothes that were hanging in the hallway into the microvan–clothes we are used to wearing!

I go to the brewery. The southern area brewery has light shining in from the roof. In the main brewery, the #8 tank has tipped off of its foundation. It’s a complete mess. The plastic cover of the small tank had slid off. At this rate, the sake will be ruined. In the freezer, the mountain of boxes for the secret stash in the freezer had toppled and many of the bottles had shattered. I couldn’t close the door. The louver doors of the southern part of the brewery won’t close. I remember that the construction of the door wasn’t that great to begin with. Only the lattice door somehow closes. The main area’s louver door was three quarters of the way closed. I want to take all of the sake that survived with me.

The three cats were apparently around. I saw Rodemu. But Eriemon does not seem to be as friendly around people as before. My wife and I took the van and I drove. I’m very sweaty and my glasses fog up. I take off my glasses to drive. I can’t see the road very well. We get separated from Mamoru and Mari’s microvan. Four cows walk along in front of the Iwano liquor store. We slip past them. We get on Rt. 114. A number of cars pass us going in the opposite direction. Fellow trespassers, go for it! A car with its lights on comes toward us. Maybe security guards! Somehow we pass them with no incident. At a place past О̄gaki we take off our masks. It’s easier to breathe now. My mask is soggy with sweat. In heading toward Katsurao, we take a wrong turn even though it’s a road we’ve taken countless times to deliver sake! I’m so stressed out! We reach Takatsuki at around noon. I immediately take a shower. We all head to the Iwaki health center for a screening. We are okay. Looking around, there were others like us who were there for a screening. I wonder if these folks were also trespassing raiders? I’m exhausted. I doze off in the car.

We unpack the things we’d brought back into the western room. We park the van in a shadowy spot behind the main gate where it is hidden from view. When we return to Takatsuki, there’s a message from Mitsumasa-san. He came while we were gone. What’s that about?!

4.7

Maybe because of yesterday’s day-long stress, I have no energy today. A mental rebound I guess. I organize the things we brought back. I guess this is what the first stormtrooping of the evacuated area looks like. I think about what we want to get during our next raid. There are still so many important things left there.

On the news, they say that they will position riot police in a twenty-kilometer perimeter around the nuclear plant. We are lucky to have missed them by a day. My wife and children are talking about the next break-in. They say that the next time Eri will join us. They are treating it like a game! They aren’t taking this seriously enough! But what about me? I managed to get my laptop out but I didn’t bring the mouse. I go to buy one. The designs and functions of new mice are incredible, but too expensive. I buy a cheap one. I regret that I didn’t bring mine from the house. That night, Mamoru and I share the BBQ shellfish that we had in the freezer and drink the sake we brought from Mitsuyo-san’s house. We recall life in Futaba. We want to live in Futaba.

4.12

My mother-in-law needs surgery. It should have been performed on March 12, but it was postponed for a week because of the earthquake. Then because most of the medical personnel evacuated and there are insufficient resources due to the nuclear accident, surgery was suspended. Today she was moved to the Iwaki City General Hospital. And tomorrow through catheter surgery, her leg veins will be widened and blood flow improved to avoid necrosis. Because it is catheter therapy, Dr. Sugi who did my heart exams will be involved. It’s so reassuring! My wife said that Dr. Sugi sent his regards to me. He kindly remembered me. Apparently he asked about the condition of my left hand. When my mother-in-law was moved from the Matsumura Hospital to the Iwaki City General Hospital, the Kyoritsu Hospital, my wife and Mamoru went along. Mitsumasa-san and his wife came later. Mitsuyo-san’s family never showed.

4.13

It’s the day of my mother-in-law’s surgery. My wife filled out all of the consent forms for surgery. My wife and Mamoru accompanied her to the surgery. The results were favorable! I feel as if it were a surgery in my family! My elder brother-in-law and his family didn’t show up for his own mother’s surgery. My wife stayed by her mother’s side until the final minute of visiting hours, and then returned home.

4.14

My mother-in-law died! In the morning, I took my wife to the Iwaki City General Hospital. I returned to Takatsuki and not long after that, I got a phone call from my wife saying that my mother-in-law had suddenly taken a turn for the worse and was in critical condition. I rushed to Hachiman shrine to let Mitsumasa-san know. Then I immediately headed to the hospital but made an error and ended up at the Workers’ Hospital. I was also pretty stunned. The cause of death occurred when they spread the vein with the catheter. A blood clot had traveled from the affected section through the bloodstream and clogged the coronary artery, which caused heart failure. As I was packing her bags in the hospital room, Mitsuyo-san and his wife Takako-san arrived. The funeral is to be held in Takatsuki. We put her bags in the two small vans. Mamoru and others were involved in clearing up the western room. It was like we were holding my family’s funeral! We parked the two small vans out of sight in the shadow of the new house.

My mother-in-law was carried in and laid in the room where my mother and wife slept. We made preparations for a Shinto funeral service. The funeral’s chief mourner will be Mitsumasa-san. Under these circumstances, this is inevitable. There’s nothing else we can do. My wife is agitated. She is angry with Mitsuyo-san. It seems to be because they closed the shrine and evacuated to Tokyo. On top of that, she couldn’t forgive Mitsuyo-san’s family for paying zero attention to my mother-in-law for fourteen years. On her deathbed, my mother-in-law was waiting until the bitter end for Mitsuyo-san. What a delicate situation! I’m at a loss for words. The funeral will be held at the end of the month. It’s quite deferred.

4.21

On the morning news, Chief Cabinet Secretary Edano announced that the area within a 20-kilometer radius of the Daiichi nuclear plant will be closed from this evening at 12 midnight! This is terrible. We quickly move the bags in the small vans into the hallway of the new house and Mamoru, Mari and my wife rush to Futaba. I remain behind, and put the baggage into a tiny storage room. My mother, who had been sleeping in the corner of the room, opens her eyes. I have her hold the edge of the bed and I change her adult diapers. Just when I am taking off the diaper, she defecates a profuse amount. I hurry to get the diaper on her. It’s awful. At last I am able to wipe her clean. As I am putting the diaper on, someone comes to pay tribute to my mother-in-law. Why do they arrive just now, at a time like this! Yesterday not a soul stopped by. I somehow got my mother laid down on the bed and hurried to greet the visitor. The visitor asked me who I am. Invoking my wife’s maiden name Iino, I replied that I am this household’s daughter’s husband. They finally left. I put my mother in her wheelchair, and take her from the new house. I set the slope bar and push my mother in the wheelchair. I wipe down the wheels of the wheelchair with newspaper. It’s hard by oneself! Mitsumasa-san came to tell my family as we were in the new house, in a half commanding way, to put her in an elderly care home. I wonder if that is even possible. Since the death of my mother-in-law, my mother is sleeping and getting up every day, but it’s hard for her to get around. Elderly care management is not as easy as Mitsumasa-san makes it out to be!

I make rice porridge with the leftover rice and have my mother eat. After our meal and cleaning up, I leave my mother on her own and go to the new house and quietly organize most of the bags we had thrown in the hallway. So much of it is Mari’s clothes. And they are hung on special hangers. I bump up against the hangers and get caught on the hooks. What a nuisance! A battle with the mountain of clothes on hangers! I get increasingly irritated. Half of the storage area is Mari’s clothes! I get angry! Weren’t there other more important things to bring?! Out of the blue, a close friend of my oldest brother-in-law and friend to my wife Hisa-san shows up. They had paid their respects at the house of someone we know well. They ask about my wife. I fib and say that she went with the children to the home of a relative who evacuated to Kо̄riyama. They won’t leave. They ask random questions about how things have been since evacuating. They finally leave. My wife’s brothers have left everything to us to take care of. No one shows their face even after he insisted on being the chief mourner and head priest. At a time like this. But it’s for the best. How ironic! The death of my mother-in-law is like when I read Shiga Naoya’s death of the bee in his short story “At Kinosaki” during high school.

I battle further with the mountain of bags. I’m sick of it! The storage closet is only as large as two tatami mats. If I put them away in the wrong order, it will be a mess. Thinking about the best method for fitting everything, I pile them up, higher than my height. I put my mother’s adult diapers and things we use frequently, like house cleaners, in a place we can get to easily. If only we didn’t have Mari’s clothes to contend with! My wife and kids return. The two cars are stuffed. We immediately unpack them into the hallways of the new house. A good portion of it is Mari’s clothes and accessories. I’m pissed! They told me that next time I should go for the raid, but, disgusted, I told them, no thanks. The three of them had cup noodles and, making a strange face, left. There is a mountain of things I want brought back from the house. I feel bad about it, but when I saw the pile of Mari’s clothing I couldn’t help but get upset.

As it grew dark, Mitsumasa-san and his wife stopped by. Relating why they’d come, they said they’d wait at the new house. Finally everyone had returned. It was pitch black. Everyone had gone to the new house and not returned. My mother and I made dinner with whatever we had at hand. After two hours, everyone returned. They ate something Mitsumasa-san had brought. Then Mitsumasa-san and his wife went home. I felt left out!

The 20-kilometer radius from the Daiichi nuclear plant was determined to be a danger zone and will be closed, but just for today they opened the barricades by authorization of the police. The roads to Futaba were apparently completely jammed. My family said they were able to connect with neighbors in Futaba. Everyone had frantically returned to their homes. On the second time back, there were cars rushing in the direction of Futaba along the dark road. Maybe they were folks who had evacuated a long distance away. I feel the advantage of being in Iwaki.

At midnight tonight, I will no longer be able to go to Futaba. My home!

I sincerely thank Satoko Oka Norimatsu for her sensitive and thorough review of the translation of Mr. Tomisawa’s hand-written diary. I am also grateful to APJ editors Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Tomomi Yamaguchi, and Matthew Penney for publishing the Diary in full.